Police Training, “Nation-Building,” and Political Repression in Postcolonial South Korea

Jeremy Kuzmarov

As American troops became bogged down first in Iraq and then Afghanistan, a key component of U.S. strategy was to build up local police and security forces in an attempt to establish law and order. This approach is consistent with practices honed over more than a century in developing nations within the expanding orbit of American global power. From the conquest of the Philippines and Haiti at the turn of the twentieth century through Cold War interventions and the War on Terror, police training has been valued as a cost-effective means of suppressing radical and nationalist movements, precluding the need for direct U.S. military intervention, thereby avoiding the public opposition it often arouses and the expense it invariably entails. Carried out by multiple agencies, including the military, State Department, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and, most recently private mercenary firms such as DynCorp, the programs have helped to fortify and gain leverage over the internal security apparatus of client regimes and provided an opportunity to export and test new policing technologies and administrative techniques, as well as modern weaponry and equipment which has all too often been used for repressive ends.

American advisers from the OSS, FBI, Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), and the New York Police Department began instructing Chinese Guomindang leader Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek)’s secret police, commanded by Dai Li, in the late 1930s. The focus, OSS agent Milton Miles wrote, was on “political crimes and means of effective repression” against the communist movement, adding that the Americans were never able to “separate police activities from guerrilla activities.” Clandestine police training in China set a precedent for Japan and South Korea under U.S. occupation, where police advisers provided training in riot control, set up modern communications and record-collection systems, and helped amass thousands of dossiers on alleged communists, weaving information into a dark tapestry of “threat” where sober analysis might have found none.2 Civil liberties and democratic standards were subordinated to larger geo-strategic goals centered on containing Chinese communist influence and rolling back the progress of the left.

Throughout the Cold War, the budget for police programs was highest in East and Southeast Asia. The United States had always prized the region as one of the richest and most strategically located in the world, hoping to convert it into what General Douglas MacArthur characterized as an “Anglo-Saxon lake.”1 In postwar South Korea, the focus of this article, the United States helped to empower former Japanese colonial agents and consolidated the rule of Syngman Rhee, an anticommunist who deployed police against leftists seeking a transformation of the political economy and reconciliation with the North. While praising the principle that police in a democratic nation should be impartial and nonpartisan, American advisers mobilized police primarily along political lines and built up a constabulary force which provided the backbone of the South Korean Army (ROKA). Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) officers used the programs to recruit agents for clandestine missions into the North, which was an important factor precipitating the Korean War. Political policing operations continued through the 1950s and 1960s, resulting in significant human rights violations. The South Korean police became known for torture and brutality, and the US bore important responsibility for this development.

Conscience and Convenience: The Consolidation of a U.S. Sphere

As Bruce Cumings notes in The Origins of the Korean War, the ROK was more of an American creation than any other postwar Asian regime. The CIA predicted that its economy would collapse in a matter of weeks if U.S. aid were terminated.3 As with Jiang Jieshi in China and Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam, U.S. diplomats tired of Syngman Rhee’s conservatism and unwillingness to promote basic land reform, though they stood by him as a bulwark against communism.The CIA considered the Princeton Ph.D. a “demagogue bent on autocratic rule”whose support was maintained by that “numerically small class which virtually monopolizes the native wealth.”4

A crucial aim of US policy was to contain the spread of the northern revolution and to open up South Korea’s economy to its former colonial master Japan thereby helping keep Japan in the Western orbit. In January 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall scribbled a note to Dean Acheson: “Please have plan drafted of policy to organize a definite government of So. Korea and connect up its economy with that of Japan.”5

The American occupation was headed by General John Reed Hodge, an Illinois farmer known as the “Patton of the Pacific,” who knew little about Korea. He worked to build a professional police force, which he believed to be pivotal to “nation-building” efforts; its central aim was to stamp out the political left and bolster Rhee’s power. A secret history of the Korean National Police (KNP) argued, “No one can anticipate what insidious infiltration may develop, and [so] the police must be given latitude to carry out the desires of the new government; more so than would be necessary in normal times.”6 The KNP consequently evolved as a politicized in the hands of many who had served in the Japanese occupation of Korea (which lasted from 1910 to 1945) and saw almost all opposition as communist driven. The CIA bluntly noted that “extreme Rightists control the overt political structure in the U.S. zone mainly through the agency of the national police,” which has been “ruthlessly brutal in suppressing disorder. . . . [T]he police generally regard the Communists as rebels and traitors who should be seized, imprisoned, and shot, sometimes on the slightest provocation.”7

During the period of Japanese rule, the national police presided over a sophisticated surveillance apparatus, dominating “every phase of daily activity,” according to the State Department, through “terror, intimidation, and practices inconceivable to the American.”8 U.S. rule was marred by colonial continuities, including a blatant carryover of personnel. In principle, occupation officials sought to purge collaborators and wipe out the vestiges of the old system by training police in democratic methods, instilling in them the maxim that they were “servants and not masters of the people.” The new police slogan, according to the Americans, was “impartial and non-partisan.”9 In practice, however, political exigencies led to the abandonment of those ideals.

The AMG retained 80 percent of pro-Japanese officers above the rank of patrolman, including northern exiles experienced in suppressing the anticolonial underground. As Colonel William Maglin, the first director of the KNP, commented, “We felt that if the Korean element of the KNP did a good job for the Japanese, they would do a good job for us.” A June 1947 survey determined that eight of ten provincial police chiefs and 60 percent of the lower-ranking lieutenants were Japanese-trained, a crucial factor triggering opposition to the police.10 To head the organization, Hodge appointed Chang T’aek-Sang and Chough Pyong-Ok, known for their “harsh police methods directed ruthlessly against Korean leftists.” Chang, a wealthy businessman with ties to the missionary community, had prospered under the Japanese. The Marine Corps historian Harold Larsen described him as “a ruthless and crass character with the face of Nero and the manners of Goering.”11

In the first days of the U.S. occupation, chaos prevailed. Prison doors were thrown open, police records were destroyed, and Koreans confiscated Japanese property, which led to violence. In some places, leftists seized power and installed their own governments. The police were demoralized and had to be accompanied on rounds by American military officers.12 A reorganization plan was drawn up by Major Arthur F. Brandstatter, who was flown in from Manila, where he had served with the military police. A bruising fullback with the Michigan State football team in the mid-1930s, Brandstatter was a veteran of the Detroit (1938–1941) and East Lansing police (chief 1946) and professor of police administration at Michigan State University. He emphasized the importance of creating standard uniforms for the KNP, improving communications, and abolishing the thought-control police, who had amassed 900,000 fingerprint files.

The United States Military Advisory Group in Korea (USMAGIK) responded to Brandstatter’s report by providing sixty-three police advisers who developed a network of thirty-nine radio stations and fourteen thousand miles of

telephone lines, resulting in the upgrading of communications facilities from “fair” to “good.” Manpower was stabilized at twenty thousand, and swords and clubs were replaced with machine guns and rifles. Americans were appointed police chiefs in every province, with the mandate of grooming a Korean successor. Typical was the background of Lieutenant Colonel Earle Miller, stationed in Kyonggi-do province, a twenty-six-year veteran of the Chicago police and supervisor of military police detachments and POW camps.13 Brandstatter, who commented in a December 1945 interview that the Koreans were “fifty years behind us in their thinking on justice and police powers” noted that high turnover among American advisers was hampering the police program and predicted that, regardless of the amount of U.S. aid, the police bureau would become a “political plum” belonging to “a big shot in the new government” (a prediction that proved accurate).14

Starting with a budget of 1.5 billion won per annum (over $1 million U.S.), the Public Safety Division rebuilt police headquarters, adopted a uniform patterned after that of the New York Police Department, and eliminated the system

in which officers were on call for twenty-four hours. It improved record collection by importing filing cabinets and oversaw the opening of a modern crime laboratory in Seoul staffed by eight Korean technicians trained in ballistics,

chemical analysis, and handwriting techniques. Police advisers recommended routine patrols to foster improved community relations, and established provincial training centers and, under Lewis Valentine’s oversight, a national

police academy, which opened on October 10, 1945. Many of the graduates, including forty-five policewomen, reportedly went on to “distinguish themselves as guerrilla fighters.” Chi Hwan Choi, a graduate of the academy, rose

to become superintendent and chief of the uniformed police.15

Staff at the academy provided training in firearms and riot control and lectures on anticommunism, and were supplied with over six thousand pistols and one thousand carbines and rifles. J. Edgar Hoover’s G-men were solicited for instruction in surveillance, interrogation and wiretapping techniques, which they had also provided to Dai Li’s secret police in China. In December 1945, USMAGIK opened a school for detectives in Seoul and established a special “subversive sub-section,” which kept a blacklist of dissidents. American training generally emphasized the development of an effective police force in light of the threats of subversion and insurgency, creating a trend toward militarization of the police.16

In January 1946, USMAGIK began developing the police constabulary, which provided the foundation for the Republic of Korea Army (ROKA). The chief adviser, Captain James Hausman, was a combat veteran who provided instruction in riot control and psychological warfare techniques such as dousing the corpses of executed people with gasoline so as to hide the manner of execution or to allow blame to be placed on the communists. Douglas MacArthur forestalled the delivery of .50-caliber machine guns and howitzers “in order to maintain [the] appearance [of the constabulary] . . . as a police-type reserve force.” Most of the officers were Japanese army veterans. Although they were not authorized to make arrests, they consistently ignored “this lack of legal right.” The constabulary gained valuable guerrilla experience suppressing rebellions in Cheju-do and Yosu, committing numerous atrocities in the process. It became infiltrated by leftists, however, who instigated several mutinies.17 Characterizing Koreans as “brutal bastards, worse than the Japanese,” Hausman worked to purge radical elements, impose discipline, and bolster intelligence gathering. At these tasks he was successful, especially in comparison to American advisory efforts in South Vietnam.18 Like the Philippines constabulary, the ROKA developed into a formidable and technically competent force. It was also renowned for its brutality, however, and became a springboard to political power, thus hindering democratic development.

“The Gooks Only Understood Force”: The Evolution of a Police State

Throughout the late 1940s, South Korea resembled what political adviser H. Merrell Benninghoff referred to as a “powder keg ready to explode.” An AMG poll revealed that 49 percent of the population preferred the Japanese occupation to the American “liberation.”19 Korea had both a tradition of radicalism and the oldest Communist Party in Asia, with experienced leaders who had led the struggle against Japan. While food imports and public health initiatives brought some benefits, land inequalities, poverty, and the desire for unification with the North made circumstances ripe for revolution, as did official corruption and heavy-handed rice collection policies enforced by the KNP. Hodge wrote in a memo that “any talk of freedom was purely academic” and that the situation left “fertile ground for the spread of communism.”20

In a February 1949 study the State Department noted, “Labor, social security, land reform, and sex equality laws have been popular in the North and appeal to South Koreans as well.” Emphasizing that although increased regimentation, heavy taxes, and the elimination of individual entrepreneurship were sowing the seeds of discontent, the northern regime still enjoyed greater popularity than that of the South because it “gave a large segment of the population the feeling of participation in government” that was absent in the South.21 This document acknowledged the lack of popular legitimacy of the southern regime, recognizing that it could survive only through force.

Resistance was led by labor and farmers’ associations and People’s Committees, which organized democratic governance and social reform at the local level. The mass-based South Korean Labor Party (SKLP), headed by Pak Hon-Yong, a veteran of anti-Japanese protest with communist ties, led strikes and carried out acts of industrial sabotage, eventually becoming infiltrated by agents of the U.S. Army Counter-Intelligence corps (CIC).22 Trained in sophisticated methods of information gathering and population control, the KNP maintained an “observation section” focused on political activity, which provided information to U.S. intelligence and at times even spied on Americans. (Ambassador John Muccio reported that the Pusan embassy was under constant surveillance by “little men with notebooks.”) With government authorities accusing almost anyone opposed to their policies of being communists and traitors, police raided homes, arrested newspaper editors for printing “inflammatory articles,” and intimidated voters during fraudulent elections, including the one in May 1948 that brought Rhee to power. In the countryside, they extracted rice from the peasantry “the same way as under the Japanese except with worse treatment,” and in cities jailed student and labor leaders and even school teachers for merely mentioning communism in their classrooms.23

Once in custody, suspects were tortured through such methods as kidney punching, hanging by the thumbnails, forced eating of hot peppers, and electroshocks in the attempt to extract confessions. A standard entry in the police registry was “died under torture” and “died of heart failure.” One prison report referred to a young girl whose face was covered because she had been struck with a rifle butt and another a man who had gone deaf from beatings. Some KNP units morphed into death squads (such as the “Black Tiger Gang,” headed by Chang T’aek-sang) and assassinated opposition figures, including, it is alleged, Yo Un-Hyong, a nationalist who promoted reconciliation between North and South.24 American military commanders often promoted brutal tactics. CIC agent Donald Nichol reported in his memoirs that the KNP were advised to “dump [untrustworthy agents] off the back of a boat, in the nude, at high speed or give him false information plants—and let the enemy do it for you.”

Despite attempts to develop professionalism, salaries were so inadequate, according to one army report, that police were “forced to beg, buy, or steal other items besides rice which go with the making of a regular diet.”Another report stated that the KNP “lacked enthusiasm” in cooperating with the army’s Criminal Investigation Division in halting the illicit sale of scrap metal and other American products, as they “often took a share of the cut.”25 American relations with Korean officials were marred by mutual mistrust. Police adviser David Fay told General Albert Wedemeyer that in his province, “not one problem of police administration had been presented to the Americans for discussion.”26

In July 1946, Captain Richard D. Robinson, assistant head of the AMG’s Bureau of Public Opinion, conducted an investigation which found police to be “extremely harsh” and intimidation such that people were afraid

to talk to Americans. Believing that oppressive methods were driving moderates into the communist camp, Robinson was outraged when he witnessed Wu Han Chai, a former machine gunner in the Japanese army, using the “water treatment” to get a suspected pickpocket to confess and had his arms forced back by means of a stock inserted behind his back and in the crooks of his elbow. When confronted, Wu said he did not believe he had done anything wrong, which appeared to Robinson to reflect a deficiency in his training. Robinson was later threatened with court-martial by Hodge’s assistant, General Archer Lerch, and was harassed by the FBI, examples of the military’s attempt to silence internal critics.27

In October 1946, at a conference to address public grievances, witnesses testified that the KNP was bayoneting students and extorting from peasants in the administration of grain collection. Due process, they said, was rarely abided by, and warrants were rarely issued. Police looted and robbed the homes of leftists and used money gained from shakedowns to entertain themselves in “Kisaeng houses” and fancy drinking and eating establishments. The head of the youth section of the Farmers’ Guild in Ka Pyung testified that he had been arrested in the middle of the night and held in a dirty cell for five days. Other leftists, including juveniles and women, spoke about being beaten to the point where gangrene set in and pus seeped out of their legs. Cho Sing Chik of Sung-Ju recounted his experience under detention of seeing a roomful of people who had been crippled by mistreatment. He stated that many of the worst abuses were committed by firemen organized into an emergency committee to support the police and collect money for them. “The police not being able to themselves beat the people turn them over to the firemen and the firemen work on them,” he declared. Another witness testified that the police were “worse than under the Japanese who were afraid to do such things [as torture]. . . . Now they have no respect for their superiors.”28

Director Chough Pyong-Ok, a Columbia University Ph.D. who made an estimated 20 million yen (about $200,000) in bribes during the first two years of the occupation, admitted that the KNP were “partial to the ideas of the rightists,” though he insisted that “all those arrested have committed actual crimes.” The CIA reported in 1948, however, that the police were taking action against known or suspected communists “without recourse to judicial process.”Stressing the importance of speedy court procedure and judicial reform in strengthening the legitimacy of the police, Robinson recommended to Hodge that he remove those who had held the rank of lieutenant under the Japanese and whose actions were “incompatible with the . . . principles of democracy in the police system.”29

Roger Baldwin, a founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, set up a branch in Korea in the attempt to abolish torture. The exigencies of maintaining power and destroying social subversion from below, however, took precedence. Pak Wan-so,a South Korean writer who had been imprisoned and tortured by the police, charged: “They called me a red bitch. Any red was not considered human. . . .They looked at me as if I was a beast or a bug. . . . Because we weren’t human, we had no rights.”30

The KNP maintained a symbiotic relationship with right-wing vigilantes, whose headquarters were located next to or inside police stations. They were described by the journalist Mark Gayn as resembling “Hollywood underworld

killers.” Their ranks were swelled by an influx of Northern refugees bearing deep grievances against communism. Chang T’aek Sang, who became prime minister, was on the board of the National Youth Association, which the CIA

characterized as a “terrorist group in support of extreme right-wing politicians.” Its head, Yi Pom Sok, was a Dai Li protégé and OSS liaison recruited in 1945 by Paul Helliwell and William Donovan of the OSS. Later appointed as defense minister, Yi received $333,000 in equipment and assistance from Colonel Ernest Voss of the internal security department to set up a “leadership academy” with courses in combating strikes and the history of the Hitler jugend (Hitler Youth), whom Yi admired.31 Opposed to the very idea of a labor union, his men beat leftists and conducted surveillance and forays across the Thirty-eighth Parallel, with CIC support. There were even attempts to assassinate Kim Il Sung.32

In the rare instances when right-wing paramilitaries were prosecuted, they were often given red carpet treatment. In May 1946 in Taejon, for example, fourteen rightists were arrested after attacking suspected communists and

stealing rice from farmers. While taking them to court, KNP officers stopped at the house of one of the prisoners and, according to internal records, enjoyed a “drunken picnic” arranged by relatives of the prisoners. In another case, the rightist gangster Kim Tu-han got off with a small fine for torturing to death two leftist youth association members and seriously injuring eight others (one of whom was emasculated). At the trial, the judge refused to call as witnesses counterintelligence officers who had taken photographs and supervised the autopsies. Such double standards were generally supported by American authorities owing to larger power considerations.33

According to information officer John Caldwell, who was ardently anticommunist and pro-Rhee, a majority of the Americans in Korea operated under the premise that “the ‘gooks’ only understood force,” a key factor accounting for the embrace of repressive methods.34 A 1948 report by the lawyers Roy C. Stiles and Albert Lyman on the administration of justice asserted that “acts considered to be cruel by western standards were only part of the tested oriental modus operandi. Low evaluation of life results in the acceptance of human cruelty.” Police adviser Robert Ferguson, a beat cop from St. Louis, commented, “Orientals are accustomed to brutality such as would disgust a white man.” Yet another report remarked that, “concepts of individual rights were incomprehensible to the oriental.

It would take much vigorous training backed by prompt punishment to change their thinking.”35 Such comments illustrate the racism that underlay the trampling of civil liberties and undermining of the progressive policing model.

In February 1948 the State Department produced a report, “Southern Korea: A Police State?” acknowledging that the KNP had a well-known “rightist bias,”which led police to assume the function of a political force for the suppression of leftist elements. Although the authors admitted that the “charges that the U.S. is maintaining a police state through its military government is not subject to flat refutation,” they held that the police programs sought to inculcate democratic principles, which are “the antithesis of a police state.” Native agencies, however, were not able to “achieve a full understanding of these principles,” owing to a “heritage of Japanese oppression” and “the fact of occupation—the excesses, disorders, and growing pains accompanying the development of a self-governing society.”36 These remarks provide a striking admission of the lack of democratic standards and illustrate the kinds of arguments adopted by public officials to absolve themselves of responsibility for the unfolding violence in the ROK.

“We’re Having a Civil War Down Here”: The October 1946 Revolts and Prison Overcrowding

According to the U.S. Army’s official history of the Korean occupation, the “public’s ill feeling toward the police, which police abuse had engendered, became a potent factor in the riots and quasi-revolts which swept South Korea

in October 1946.”37 In South Cholla province, after the KNP killed a labor leader, Njug Ju Myun, and jailed unemployed coal miners celebrating the first anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japan, angry peasants dynamited a police box and ambushed a prisoner convoy by throwing stones. Constabulary detachments hunted those deemed responsible with the assistance of American troops, firing into crowds. Hundreds died or were injured. An editorial proclaimed: “We cannot take the humiliation any longer and must fight against imperialism and the barbarity of the U.S. Army. . . . In North Korea, Japanese exploitation was abolished and land was given back to the people through the agrarian and labor laws. In South Korea, the property of the Japanese imperialists was taken over by the Americans and Korean reactionary elements. . . . The people are suffering from oppression and exploitation. This is democracy?”38

Such sentiments lay at the root of mounting civil strife across the country, to which authorities responded the only way they knew how—with further police repression and violence. In Taegu, martial law was declared after riots

precipitated by police suppression of a railroad strike left thirty-nine civilians dead, hundreds wounded, and thirty-eight missing. Fifteen hundred were arrested, and forty were given death sentences, including SKLP leader Pak, who fled to the North. Over 100,000 students walked out in solidarity with the workers, while mobs ransacked police posts, buried officers alive, and slashed the face of the police chief, in a pattern replicated in neighboring cities and

towns. (In Waegwon, rioters cut the police chief’s eyes and tongue.)39 Blaming the violence on “outside agitators” (none were ever found) and the “idiocy” of the peasants, the American military called in reinforcements to restore order. Colonel Raymond G. Peeke proclaimed, “We’re having a civil war down here.” The director of the army’s Department of Transportation added: “We had a battle mentality. We didn’t have to worry too much if innocent people got hurt. We set up concentration camps outside of town and held strikers there when the jails got too full. . . . It was war. We recognized it as war and fought it as such.”40

By mid-1947, after the AMG passed a national security law expanding police powers, there were almost 22,000 people in jail, nearly twice as many as under the Japanese. KNP director William Maglin later acknowledged in a

1999 article that “in their retaliation for murders and indignities [during the 1946 riots] police went too far in arresting large numbers of communists, leftists, and leftist sympathizers.” Many were sentenced by military tribunal, while others languished in prison without counsel. Thousands were held in outlying camps, including seven members of the National Assembly charged with leading a “communist conspiracy.”41

During an inspection of Wanju jail, Captain Richard D. Robinson found six prisoners sharing a mosquito-infested twelve-foot-by-twelve-foot cell accessible only through a small trapdoor and tunnel. In other facilities, inmates were beaten and stripped naked to keep them from committing suicide. The latrine was usually nothing but a hole in the floor. Food was inadequate, winter temperatures were sub-zero, and medical care was scant. Prisoners were not allowed to write letters or have outside communications and usually had to sleep standing up. In Suwan, inmates were forced to sleep in pit cells without heat. Their water was drawn from a well located next to a depository for raw sewage, causing rampant disease, including a scabies epidemic.42

In April 1948, to relieve overcrowding, Major William F. Dean, a onetime Berkeley patrolman, recommended the release of 3,140 political prisoners whose offense consisted only of “participation in illegal meetings and demonstrations and distributing handbills.”43 Authorities established work camps in order to “utilize the capabilities of the inmates in useful occupations,” which often entailed performing duties for the American military. Enacting the ideals of the progressive movement, U.S. advisers introduced vocational training, a rewards system, prison industries, and movies and recreation. They brought in chaplains, constructed juvenile facilities, and established a guard training school with courses in modern penology, fingerprinting, and weapons.44

What effect the reforms had is unclear; what is certain is that prisons remained riddled with abuse. According to the U.S. Army, guards displayed a “harshness that was repugnant to Department of Justice legal advisers.” At the Inchon Boys’ Prison, inmates were deprived of exercise and forced to work at making straw rope without sufficient light. Prisoners engaged in hunger strikes and led jail breaks. In Kwangju on August 31, 1947, 172 inmates overpowered guards, and seven drilled their way to freedom. Two years later in Mokpo, near Seoul, 237 guerrillas from Cheju Island were killed by police and U.S. Army soldiers after breaking free into the neighboring hills; another eighty-five were captured alive.45 In sum, the prison conditions contradict the myth that the American influence in South Korea was benign. As in later interventions, the repressive climate catalyzed the opposition and hastened armed resistance.

“A Cloud of Terror”: The Cheju Massacre and Korean War Atrocities

Some of the worst police crimes occurred in suppressing the uprising on the island of Cheju at the southern tip of the country. The source of the upheaval was unequal land distribution and police brutality, as the CIA acknowledged. Hodge ironically told a group of congressmen that Cheju was a truly“communal area . . . peacefully controlled by the People’s Committee,” who promoted a collectivist and socialist philosophy “without much Comintern influence.”46 In March 1947, as the AMG tried to assert its authority, the KNP fired into a crowd and killed eight peaceful demonstrators, then imprisoned another four hundred. Governor Pak Kyong-jun was dismissed and replaced by Yu Hae-jin, an extreme rightist described as “ruthless and dictatorial in his dealing with the opposing political parties.47 KNP units and right-wing youth groups terrorized the People’s Committee and cut off the flow of food and construction supplies, turning the island into an open-air prison. In response, the Cheju branch of the SKLP, long known for its anticolonial defiance, established guerrilla units in the Halla Mountains supported by an estimated 80 percent of the population.48 In April 1948 the rebellion spread to the west coast of the island, where guerrillas attacked twenty-four police stations. KNP and constabulary units operating under U.S. military commandand aided by aerial reinforcements and spy planes swept the mountains, waging “an all-out guerrilla extermination campaign,” as Everett Drumwright of the American embassy characterized it, massacring people with bamboo spears and torching homes. One report stated, “Frustrated by not knowing the identity of these elusive men [the guerrillas], the police in some cases carried out indiscriminate warfare against entire villages.” Between 30,000 and 60,000 people were killed out of a population of 300,000, including the guerrilla leader Yi Tôk-ku, and another 40,000 were exiled.49

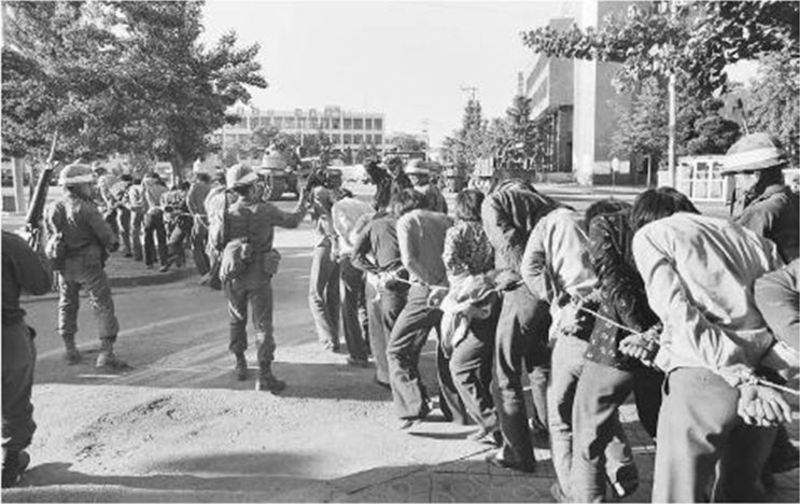

Police atrocities in the suppression of the insurrection in Yosu left that port town in ashes. After the declaration of martial law on October 22, 1948, constabulary units under Captain James Hausman rounded up suspected rebels, stripped them to their underwear in schoolyards, and beat them with bars, iron chains, and rifle butts. Cursory screenings were undertaken, and several thousand were executed in plain sight of their wives and children in revenge for attacks on police stations. The corpses of many of the dead were placed in city streets with a red hammer and sickle insignia covering the chest. Order was restored only after purges were conducted in constabulary regiments that had mutinied in support of the rebel cause, and the perpetrators executed by firing squad.50

The Yosu and Cheju massacres contributed to the decimation of the leftist movements, which deprived Kim Il-Sung’s armies of support after crossing into South Korea on June 25, 1950, precipitating the Korean War. When fighting broke out, the KNP, expanded to seventy thousand men, joined in combat operations, later receiving decorations for “ruthless campaigns against guerrilla forces.” Many officers were recruited for secret missions into North Korea by the CIA’s Seoul station chief, Albert Haney, a key architect of the 1290-d program, and Hans Tofte, a hero of the Danish underground who later served under OPS cover in Colombia. A large number were killed, owing to the infiltration of the secret teams by double agents, though Haney doctored the intelligence reports to cover up their fate.51

In the summer of 1950, to keep Southern leftists from reinforcing the Northerners, KNP and ROKA units emptied the prisons and shot as many as 100,000 detainees, dumping the bodies into hastily dug trenches, abandoned mines, or the sea. According to archival revelations and the findings of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, women and children were among those killed.52 The British journalist James Cameron encountered prisoners on their way to execution only yards from U.S. Army headquarters and five minutes from the UN Commission building in Pusan. “They were skeletons and they cringed like dogs,” he wrote. “They were manacled with chains and . . . compelled to crouch in the classical Oriental attitude of subjection. Sometimes they moved enough to scoop a handful of water from the black puddles around them . . . . Any deviation . . . brought a gun to their heads.”53

The most concentrated killing occurred in the city of Taejon, where the KNP slaughtered thousands of leftists under American oversight. Official histories long tried to pin the atrocity on the communists. The conduct of the KNP was

not an aberration, however, but the result of ideological conditioning, training in violent counterinsurgency methods by the Americans and Japanese, and the breakdown of social mores in the war. H istorian Kim Dong- Choon described the police killings represented among the “most tragic and brutal chapters” of a conflict that claimed the lives of 3 million people and left millions more as refugees.54

Managing the Counterrevolution: Police Training and “Nation-Building” in South Korea in the War’s Aftermath

OPS adviser Robert N. Bush and South Korean Counterpart. Courtesy Sgt. Gary Wilkerson, Indiana State Police. OPS adviser Robert N. Bush and South Korean Counterpart. Courtesy Sgt. Gary Wilkerson, Indiana State Police. |

The Korean War ended in stalemate in 1953. Syngman Rhee remained leader of the ROK until his death in 1960, when, after a brief power struggle, he was replaced by General Park Chung Hee. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, American policy elites conceived of South Korea as a laboratory for the promotion of free-market capitalism and modernizing reforms.55

Operating on a budget of $900,000 per year, police programs were designed to wipe out the last vestiges of guerrilla resistance and promote the stability on which economic development could take root. Concerned about police corruption and outdated technical equipment, the CIA noted that South Korea had emerged from the war with a “rigid anti-communist national attitude and vigilant . . . repressive internal security system . . . which has resulted in the virtual elimination of all but the most covert and clandestine communist operators.”56 Various revenge regiments were in existence, whose mission was to hunt down Northern collaborators. American training focused on building up espionage and “counter-subversive” capabilities, creating a central records system, and lecturing on the severity of the “communist threat.” U.S. military advisers oversaw police units carrying out “mop-up” (death squad) operations against “bandits” and spies, in which civilian deaths were widely reported. In a precursor to the Vietnam Phoenix program, efficiency was measured by the number of weapons seized and guerrillas captured and “annihilated,” usually at least four times more than the number of police wounded or killed.57

Typical was a report in February 1954 in which adviser Edward J. Classon lauded the discovery and destruction of an enemy hideout in Sonam in which thirty-one “bandits” were killed and fifty-four captured.58 Another report referred to a police drive in December 1953, Operation Trample, which “reduced the number of ‘bandits’ from 691 to only 131 [in the Southern Security Command],” the remainder of whom were now “widely scattered” and “represented little danger to the population.”59

In the face of repression and waning support among a war-weary population, guerrillas resorted to kidnapping and extortion in an attempt to survive. A police report dated May 1, 1954, noted that five “bandits” under the cover of darkness raided the homes of two farmers, tied up their families, and demanded millet, salt, potatoes, and clothing, which gives a good sense of their desperation.60 In December 1956, public authorities announced the success of pacification efforts. They claimed to have arrested the last known “guerilla bandits” of the anti-American regiment, a seventeen-year-old girl, Koon Ja Kim, and eighteen-year-old Sam Jin Koh, in a mop-up campaign in Chullo-Pukto province. Seven subversives were shot, including commander Kaun Soo Pak, age thirty-three. The photos of Koon and Sam under police arrest were broadcast in the Korea Times in order to publicize the KNP’s strength in reestablishing law and order.61

Throughout the duration of Rhee’s rule, the police remained mobilized for paramilitary operations. Interference in elections and ballot stuffing remained prevalent, as did customary practices such as surveillance, black propaganda, and torture.62 Rhee used the police to undertake “extralegal and violent tactics” against opponents. In April 1960, police opened fire on student demonstrators protesting the recent fraudulent elections, killing or wounding several hundred. Koreans in the United States picketed the White House, demanding that America take a stand against “the brutal, degrading butchery.”63

The Korea Times reported on the arrest and beating of Kim Sun-Tae, an MP, after he protested staged elections in 1956. Lee Ik-Heung, minister of home affairs, and Kim Chong-Won, head of the public security bureau, who worked closely with Captain Warren S. Olin, a career army officer, ordered troopers to “nab the bastard” and kept him in detention for five days, during which time he was “treated like a dog.” The newspaper editorialized, “There can never be a representative democracy with men like Lee and Kim in positions of power.”64 Born to a poor Korean family in Japan, Kim Chong-Won was trained in the 1930s in Japanese military academies, whose rigorous ideological conditioning and harsh, dehumanizing methods set the course for his career. Known as the “Paektu Mountain Tiger,” he decapitated suspected guerrilla collaborators during the suppression of the Yosu rebellion with a Japanese-style sword and machine gunned thirty-one detainees in the Yongdok police station. In Yonghaemyon, Kim’s men arrested civilians after finding propaganda leaflets at a nearby school and shot them in front of villagers, opening fire on women and children who ran from the scene. Over five hundred were killed in the massacre, for which Kim was sentenced to three years in prison, though he was amnestied by Rhee.65

“Tiger” Kim presided over further atrocities as vice commander of the military police in Pusan during the Korean War. His appointment as head of the public security bureau was a reward for his loyalty to Rhee and reflected the KNP’s continued emphasis on counterinsurgency and utter disregard for human rights. Ambassador John Muccio, who later oversaw another dirty war in Guatemala, characterized Kim’s methods as “ruthless yet effective,” typifying U.S. support for brutal tactics, as long as they were directed against “communists.”66

|

|

Viewing the police programs as a great success, the State Department sought to replicate them in Vietnam, where the U.S. and the French faced a similar problem of communist infiltration and an “inability to distinguish friend from foe.” Colonel Albert Haney, in his internal outline of the 1290-d program, boasted that “U.S efforts behind the ROK in subduing communist guerrillas in South Korea, while not generally known, were exceptionally effective at a time when the French were spectacularly ineffective in Indochina.”On May 27, 1954, Lieutenant Colonel Philippe Milon of the French army was briefed by American officials on KNP techniques of surveillance and population control,, which he sought to incorporate as a model.67

In 1955, after transferring police training to the State Department under 1290-d, the Eisenhower administration provided over $1 million in equipment to the KNP. Lauren “Jack” Goin, an air force officer with B.A. and M.S. degrees in criminology from the University of California at Berkeley and director of the Allegheny Crime Lab in Pittsburgh, set up a scientific crime lab equipped with fingerprinting powders and the latest forensic technology. (He later did the same in Vietnam, Indonesia, Dominican Republic, and Brazil.)68 Advisers from Michigan State University’s Vietnam project, including Jack Ryan, Ralph Turner, and Howard Hoyt, served as consultants and helped set up a communication system. They then went on to Taipei, where, on a visit sponsored by the CIA-fronted Asia Foundation, they instructed police led by the Generalissimo’s son Chiang Ching-kuo in rooting out Maoist infiltration.69

The 1290-d police training program in South Korea was headed by Ray Foreaker, retired chief of police in Oakland, and a twenty-seven-year veteran of the Berkeley police force, where he had been mentored by August Vollmer, the “father of modern law enforcement.” During his tenure as Berkeley chief, Vollmer pioneered many innovations, including the use of fingerprinting, patrol cars, and lie detector tests. A veteran of the Spanish-American War who cut his teeth training police in Manila, Vollmer was more liberal than many of his contemporaries in defending communists’ right to free assembly and speech and in criticizing drug prohibition laws. He worked to curtail the “third degree” and embraced a social work approach to policing, visiting local jails each morning to talk to inmates and urging his officers to interact with members of the community on their beat.70

Apart from in his attitude toward communism, these are the kinds of ideals that Foreaker, a specialist in criminal and security investigations, sought to promote in South Korea, and later in Indonesia, Ethiopia, Guatemala, and Vietnam. He commented, “Our work here [in the 1290-d program] is in the total field of public safety rather than in police work alone.”71 Foreaker’s successor as Oakland police chief, Wyman W. Vernon, was part of the advisory team, later serving in Vietnam and Pakistan. Like Foreaker, he had a reputation as an incorruptible reformer, having established a special planning and research unit in Oakland staffed by Berkeley students to analyze and address police problems, including poor relations with minorities. The Oakland police nevertheless continued to be viewed as an army of occupation in the black community, their brutalization of antiwar demonstrators and Black Panthers during the 1960s exemplifying the limits of the Berkeley professionalization model.72 Shaped by the conservative, hierarchical, and lily-white institutional milieu from which they came, Foreaker and Vernon were generally ill-equipped to bring about enlightened police practice in South Korea, where they faced an alien cultural environment and a war climate that brought out the most violent tendencies of the police.

In the attempt to instill greater professionalism, the State Department sent twenty top-ranking KNP, including General Hak Sung Wang, head of the national police college, and Chi Hwan Choi, chief of the uniformed police, trained by the Americans in the 1940s, for courses at the FBI Academy and at leading criminology institutes such as Berkeley, Michigan State University, and the Northwestern Traffic Institute.73 A dozen more were sent to the Los Angeles Police Department, headed by Chief Willie Parker (1950–1966), who was known for cleaning up corruption and for his right-wing politics and insensitivity toward racial minorities and the poor.74

Korean officers trained in prison management at George Washington University returned home to reform the ROK penal system. Drawing on the ideals of progressive penology, they revived efforts to establish rewards and parole, promoted industrial training, and created juvenile reformatories to address skyrocketing delinquency rates resulting from a profusion of war orphans. The PSD pledged $553,688 and assisted in developing a work farm outside Seoul based on the Boys Town juvenile detention center in Nebraska.75

Coinciding with the passage of mandatory minimum sentencing for drug offenses in the United States, the International Cooperation Administration established police counter-narcotics units, which raided opium dens and launched Operation Poppy, deploying army aviation units to detect and destroy poppy fields.76 These campaigns were undermined by police and governmental corruption. A report from the U.S. Army’s Criminal Investigation Division pointed to ties between Japanese gangster Machii Hisayuki (known in Korea as Ko Yung Mok) and ROK naval intelligence, stating that he was “too strong politically to be touched by the police,” despite having murdered a Korean boxer. American troops also participated in the black market, working with their Korean girlfriends and local “slickie” boys to sell drugs, cigarettes, and pirated consumer goods such as watches, cameras, and radios.77 Their involvement in crimes, including vehicular manslaughter, arson, rape, and murder, dominate police reports of the period.78

In the late 1950s, the State Department suspended the police programs, acknowledging their contribution to widespread human rights violations. The United States was integral in creating a repressive internal security apparatus that made even hardened Cold Warriors blanch. A 1961 cabinet-level report tellingly referred to the KNP as the “hated instrument of the Rhee regime.”79 The Kennedy administration nevertheless revived police training under Rhee’s successor, Park Chung Hee, a former member of the South Korean Communist Party who later hunted Korean resistance fighters in Manchuria during World War II with the Japanese Imperial Army. After mutinying during the 1948 Yosu rebellion, General Park escaped execution by informing on onetime associates, allegedly including his own brother, and subsequently rose through the military hierarchy with the assistance of Captain Hausman, who remained in country as a liaison with the ROKA. After the 1961 coup in which Park seized power, he presided over a period of spectacular economic growth, resulting from visionary state planning, technological development, war profiteering, and a massive interjection of foreign capital.80 The ROK Supreme Council meanwhile passed a law mandating the purification of political activities. Living conditions remained difficult for the majority, as Park collaborated with the management of large chaebol (conglomerates) in using police and hired goons to suppress strikes, and keeping wages low in order to attract foreign investment. Forbes magazine glowingly promoted South Korea in this period as a great place to do business because laborers worked sixty hours per week for very low pay.81

Characterized as a quasi-military force, the KNP retained a crucial role in suppressing working-class mobilization and monitoring political activity. Surveillance was coordinated with the Korean Central Intelligence Agency which was developed out of police intelligence units trained by the United States. OPS advisers in the CIA—including Arthur M. Thurston, who left his official job as chairman of the board of the Farmers National Bank in Shelbyville, Indiana, for months at a time, telling friends and family he was going to Europe—helped set up intelligence schools and a situation room facility equipped with maps and telecommunications equipment. By the mid-1960s, Korean Central Intelligence had 350,000 agents, out of a population of 30 million, dwarfing the Russian NKVD at its height. CIA attaché Peer De Silva rationalized its ruthless methods by claiming, “There are tigers roaming the world, and we must recognize this or perish.”82

From 1967 to 1970 the OPS team in Korea was headed by Frank Jessup, a Republican appointee as superintendent of the Indiana State Police in the mid- 1950s and veteran of police programs in Greece, Liberia, Guatemala, and Iran. A sergeant with the Marine Corps Third Division who served in counterintelligence during the Pacific war and as chief of civil defense with the U.S. federal police, Jessup was a national officer of the American Legion. Lacking any real knowledge of Korean affairs, he subscribed to the worldview of the American New Right, with its commitment to social order, military preparedness, and counterrevolutionary activism at home and abroad. His politics were characteristic of the advisory group, which included William J. Simmler, chief of detectives in Philadelphia, with experience in the Philippines; Peter Costello, a twenty-four-year veteran of the New York Police Department, who helped run the dirty war in Guatemala; and Harold “Scotty” Caplan of the Pennsylvania State Police.

Peaking at a budget of $5.3 million in 1968, the OPS organized combat police brigades and village surveillance and oversaw the interrogation of captured agents and defectors. It also improved record management, trained industrial

security guards, oversaw the delivery of 886 vehicles (35 percent of the KNP fleet), and provided polygraph machines and weaponry such as gas masks and grenade launchers.83 The KNP claimed to have apprehended 80 percent of North Korean infiltrators as a result of American assistance.84

Sweeping under the rug the tyrannical aspects of Park’s rule, modernization theorists in Washington considered U.S. policy in South Korea to be a phenomenal success because of the scale of economic growth, which was contingent in part on manufacturing vital equipment for the American army in Vietnam. The United States was especially grateful to Park for sending 312,000 ROK soldiers to Vietnam, where they committed dozens of My Lai–style massacres and, according to a RAND Corporation study, burned, destroyed, and killed anyone who stood in their path.85 The participation of police in domestic surveillance and acts of state terrorism was justified as creating a climate of stability, allowing for economic “take-off.” Together with Japan, South Korea helped crystallize the view that a nation’s police force was the critical factor needed to provide for its internal defense.86

|

|

In January 1974, President Park passed an emergency measure giving him untrammeled power to crack down on dissenters. Amnesty International subsequently reported an appalling record of police detentions, beatings, and torture of journalists, churchmen, academics, and other regime opponents. Leftists (dubbed chwaiksu) confined in overcrowded prisons were forced to wear red badges and received the harshest treatment.87 In May 1980, KNP and

ROKA officers, a number of them Vietnam War veterans, killed up to three thousand people in suppressing the Kwangju pro-democracy uprising. Students were burned alive with flamethrowers as the officers laid siege to the city. A popular slogan from the period proclaimed, “Even the Japanese police officers and the communists during the Korean War weren’t this cruel.” These words provide a fitting epitaph to the American police programs, which, over a thirty-five-year period, trained some of the forces implicated in the massacre and provided the KNP with modern weaponry and equipment used for repressive ends.88

In a study of police torturers in the Southern Cone of Latin America, Martha K. Huggins and a team of researchers concluded that ideological conditioning and the political climate of the Cold War helped shape their behavior and allowed for the rationalization of actions that the perpetrators would normally have considered abhorrent, and now do in the clear light of day.89 Their insights are equally applicable to South Korea, where police violence was justified as saving the country from a dangerous enemy. Conceiving of police as crucial to broader state-building efforts, the American programs were designed in theory to professionalize police standards and incorporate the kinds of progressive style reforms that were prevalent in the United States. However, they became heavily militarized and focused on the suppression of left-wing activism, resulting in systematic human rights violations. American intervention empowered authoritarian leaders and provided security forces with modern surveillance equipment, forensics technology, and weapons which heightened their social control capabilities. The vibrancy of the labor movement and political left was curtailed, thus contributing to a weakening of civil society. The working classes were largely left out of the Park-era economic boom, and North-South rapprochement was made impossible. Throughout the Cold War, challengers of the status quo were subjected to imprisonment, torture, and often death. Their plight has largely been suppressed in the West, along with the buried history of U.S.-ROK atrocities in the Korean War. Undisturbed by all the bloodshed, the practitioners of realpolitik in Washington viewed the intervention in South Korea as an effective application of the containment doctrine. Police advisers were consequently called upon to pass along their technical expertise so as to fend off revolution in other locales, including South Vietnam, again with cataclysmic results.

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Jay P. Walker Assistant Professor of History at the University of Tulsa. He is the author of Modernizing Repression. Police Training and Nation-Building in the American Century and The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs.

This is a revised and expanded version of chapter four in Modernizing Repression.

Recommended Citation: Jeremy Kuzmarov, “Police Training, ‘Nation-Building,’ and Political Repression in Postcolonial South Korea,”The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 27, No. 3, July 2, 2012.

Notes

1MacArthur quoted in John Dower, “The U.S.-Japan Military Relationship,” in Postwar Japan, 1945 to the Present, ed. Jon Livingston, Joe Moore, and Felicia Oldfather (New York: Pantheon, 1973), 236. On the long-standing U.S. drive for hegemony in the Asia-Pacific, see Bruce Cumings, Dominion from Sea to Sea: Pacific Ascendancy and American Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); Richard Drinnon, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980). For strategic planning after World War II, see Noam Chomsky, For Reasons of State (New York: New Press, 2003).

2 See Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009); Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War: vol. 2 , The Roaring of the Cataract, 1947–1950 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 31.

3 Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War: vol. 1, Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945–1947 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981); “The Position of the U.S. with Respect toKorea,” National Security Council Report 8, April 2, 1948, PSF, Truman Papers, HSTL.

4 Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, Korea: The Unknown War (New York: Pantheon,1988), 23; Dong-Choon Kim, The Unending Korean War: A Social History, trans. Sung-ok Kim (Larkspur, Calif.: Tamal Vista Publications, 2000), 80. When asked by the journalist Mark Gayn whether Rhee was a fascist, Lieutenant Leonard Bertsch, an adviser to General John R. Hodge, head of the American occupation, responded, “He is two centuries before fascism—a true Bourbon.” Mark Gayn, Japan Diary (New York: William Sloane, 1948),352.

5 Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: Norton, 1997), 210.

6 “A History of the Korean National Police (KNP),” August 7, 1948, RG 554, United States Army Forces in Korea, Records

Regarding the Okinawa Campaign (1945–1948), United States Military Government, Korean Political Affairs, box 25 (hereafter USAFKIK, Okinawa).

7 Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, vol. 2, The Roaring of the Cataract, 1947–1950, rev. ed. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 186, 187; Gregory Henderson, Korea: The Politics of the Vortex (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968), 143.

8 Roy C. Stiles and Albert Lyman, “The Administration of Justice in Korea under the Japanese and in South Korea under the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea to August 15, 1958: Paper by American Advisory Staff,” Department of Justice, RDS, Records Related to the Internal Affairs of Korea, 1945–1949, decimal file 895 (hereafter cited RDS, Korea.

9 Harry Maglin, “Organization of National Police of Korea,” December 27, 1945, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; Everett F. Drumright to Secretary of State, “FBI Training,” December 22, 1948, RDS, Korea; Philip H. Taylor, “Military Government Experience in Korea,” in American Experiences in Military Government in World War II, ed. Carl J. Friederich (New York:

Rinehart, 1948), 377; Harold Larsen, U.S. Army History of the United States Armed Forcesin Korea, pt. 3, chap. 4, “Police and Public Security” (Seoul and Tokyo, manuscript in theOffice of the Chief of Military History, 1947–48).

10 Gayn, Japan Diary, 390; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:164; Col. William H. Maglin, “Looking Back in History: . . . The Korean National Police” Military Police Professional Bulletin (Winter 1999): 67–69; John Muccio to Secretary of State, August 13, 1949, Department of Justice, RDS, Korea. Ch’oe Nûng-jin (“Danny Choy”), chief of the KNP Detective Bureau, called the KNP “the refuge home for Japanese-trained police and traitors,” including “corrupt police who were chased out of North Korea by the communists.”Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:166, 167. In North Korea, by contrast, police officers during the colonial period were purged, and authorities worked to rebuild a new police force of people without collaborationist backgrounds. This was a factor accounting for the legitimacy of the revolutionary government, Charles Armstrong notes, although the security structure still built on the foundations of the old in its striving for total information control. Armstrong, The North Korean Revolution, 1945–1950 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 205.

11 Edward Wismer, Police Adviser, to Director of National Police, June 6, 1947, USAFIK, RG 554, Records Regarding Korean Political Affairs (1945–1948), box 26; Kim, The Unending Korean War, 185; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:502. An American police supervisor commented that there was enough evidence on both Chang and Chough to“hang them several times over” (ibid.). Hodge justified their appointment by pointing to their fierce anticommunism and loyalty to the American command. The CIA characterized Chang, managing director of the bank of Taegu in the 1940s who hailed from one of Korea’s oldest and wealthiest families, as “an intelligent, ambitious opportunist who, while basically friendly to the United States, is erratic and unreliable when excited.” NSCF, CIA,box 4, HSTL.

12 Stiles and Lyman, “The Administration of Justice in Korea under the Japanese and in South Korea under the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea to August 15, 1958” RDS, Korea; “History of the Korean National Police,” August 7, 1948, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; Larsen, “Police and Public Security,” 5, 6.

13 “Interview with Lt. Col. Earle L. Miller, Chief of Police of Kyonggi-do, 15 Nov. 1945to 29 Dec. 1945,” February 3, 1946; Harry S. Maglin, “Organization of National Police of Korea,” December 27, 1945, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” September 1946, GHQ-SCAP, 18; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” February 1948, GHQ-SCAP, 187; Arthur F. Brandstatter, Personnel File, Michigan State University Archives.

14 “Interview with Major Arthur F. Brandstatter, Police Bureau, 7 December 1945,” USAFIK Okinawa, box 25.

15 “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” November 13, 1945, GHQ-SCAP; “History of the Korean National Police,” August 7, 1948;“Police Bureau Renovates Good But Wrecked System,” The Corps Courier, February 12, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 26; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” September 1946, GHQ-SCAP, 18; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” February 1948, GHQ-SCAP, 187; “Chief of Korean Uniformed Police Visits U.S. Provost Marshall,” Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science 44 (July–August 1953): 220.

16 “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” November 13, 1945, USAFIK Okinawa, box 26; J. H. Berrean to Major Millard Shaw, Acting Advisor, Department of Police,July 27, 1948, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; D. L. Nicolson to J. Edgar Hoover, March 29, 1949, RDS, Korea, file 895; Henderson, Korea, 142–43. On the Chinese precedent, see Mary Miles,“The Navy Launched a Dragon,” unpublished manuscript, Naval War College, Newport,R.I., chap. 28, “Unit Nine, School of Intelligence and Counter-Espionage.”

17 Major Robert K. Sawyer, Military Advisers in Korea: KMAG in Peace and War, The United States Army Historical Series, ed. Walter G. Hermes (Washington, D.C.: OCMH,GPO, 1962), 13; Bruce Cumings, The Korean War: A History (New York: Random House, 2010), 134; Peter Clemens, “Captain James Hausman, U.S. Military Adviser to Korea,1946–1948: The Intelligence Man on the Spot,” Journal of Strategic Studies 25, no. 1 (2002):184; John Merrill, Korea: The Peninsular Origins of the War (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1989), 100.

18 Allan R. Millett, “Captain James R. Hausman and the Formation of the Korean Army, 1945–1950,” Armed Forces and Society 23 (Summer 1997): 503–37; Clemens, “Captain James Hausman,” 170; Allan R. Millett, The War for Korea, 1945–1950: A House Burning (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005), 173.

19 Joyce Kolko and Gabriel Kolko, The Limits of Power: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1945–1954 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), 290; Richard D. Robinson, “A Personal Journey through Time and Space,” Journal of International Business Studies 25, no.3 (1994): 436.

20 Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:267; Henderson, Korea, 145; Richard C. Allen, Korea’s Syngman Rhee: An Unauthorized Portrait (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1960).

21 Max Bishop to Charles Stelle, “Answers to Questions on the Korean Situation in Light of the Withdrawal of Soviet Troops,” February 10, 1949, RG 59, RDS, Records of the Division of Research for Far East Reports (1946–1952), box 4, folder 1.

22 Armstrong, The North Korean Revolution; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:267; Donald Nichol, How Many Times Can I Die? (Brooksville, Fla.: Vanity Press, 1981),119; John Reed Hodge to Douglas MacArthur, September 27, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box25; “Communist Capabilities in South Korea,” Office of Reports and Estimates, CIA, February 21, 1949, PSF, Truman Papers, HSTL.

23 “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” September 1946, GHQ-SCAP, 18; “Strikes/Riots,” September 1946–May 1947, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25, folder 3; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” September 1946, GHQ-SCAP, 17; 27; Everett F. Drumright to Secretary of State, “Amending of Organization of National Traitors Acts,” December 22, 1948, RDS, Korea, file 895; Henderson, Korea, 146; Richard D. Robinson, “Betrayal of a Nation,” unpublished manuscript, 1960, 147 (courtesy of Harvard Yenching Library); Daily Korean Bulletin, June 14, 1952, NSCF, CIA, box 4, HSTL. Lee Sang Ho, editor of the suspended Chung Ang Shin Mun, and Kwang Tai Hyuk, chief of the newspaper’s administrative section, were characteristically sentenced to eighteen months’ hard labor for printing “inflammatory articles.” For harsh police repression of the labor movement, see Hugh Deane, The Korean War, 1945–1953 (San Francisco: China Books, 1999), 40.

24 Millard Shaw, “Police Comments on Guerrilla Situation,” August 6, 1948, USAFIK Okinawa, box 26; George M. McCune, Korea Today (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950), 88; Kim, The Unending Korean War, 186; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War,2:207. U.S. military intelligence may have collaborated in the assassination of another of Rhee’s rivals, Kim Ku, who was opposed to American intervention. Ku’s assassin, An Tu-hui, was released from Taejon penitentiary after a visit by a U.S. Army counterintelligence officer and was afterwards promoted to army major.

25 Nichol, How Many Times Can I Die, 135; “Summary Conditions in Korea,” November 1–15, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” June 1947, GHQ-SCAP, 26. Some of these rackets involved U.S. soldiers. An army colonel, for example, looted over four thousand cases of precious artworks from museums, shrines and temples. After he was caught, he was sent home on “sick leave.” Robinson, “Betrayal of a Nation,” 290.

26 Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2:188.

27 “History of the Police Department,” USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; Robinson, “A Personal Journey through Time and Space,” 437; Robinson, “Betrayal of a Nation,” 155. In North Korea, while dissidents were sent to labor and “re-education” camps, the use of torture to extract confessions was abolished and according to the leading authority on the revolution, rarely practiced. Armstrong, The North Korean Revolution, 208.

28 “Korean-American Conference,” October 29, 1946; and “Report Special Agent Wittmer, G-2,Summary, November 3, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, boxes 25 and 26.

29 “Korean-American Conference”; Robinson, “Betrayal of a Nation,” 151; “South Korea: A Police State?” February 16, 1948, RDS, Division of Research for Far East Reports (1946– 1952), box 3; “Communist Capabilities in South Korea.”

30 Kim, The Unending Korean War, 123.

31 James I. Matray, The Reluctant Crusade: American Foreign Policy in Korea, 1941–1950 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985), 77; Gayn, Japan Diary, 371. Yi Pom Sok’s OSS connections are revealed in Robert John Myers, Korea in the Cross Currents: A Century of Struggle and the Crisis of Reunification (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 74.

32 Adviser Millard Shaw considered the cross-border operations acts “bordering on terrorism” which “precipitate retaliatory raids . . . from the North.” Report, Major Millard Shaw, Acting Advisor, “Guard of the 38th Parallel by the National Police,” November 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25, folder 3; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2:195. The first to challenge the standard interpretation was I. F. Stone in The Hidden History of the Korean War (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969), originally published in 1952.

33 “Police Fraternization and Being Bribed by Prisoners,” August 28, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 26, folder 10; G-2 Periodic Report, “Civil Disturbances,” Seoul, Korea, September 1947, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; Henderson, Korea, 144.

34 Kolko and Kolko, The Limits of Power, 288; John Caldwell, with Lesley Frost, The Korea Story (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1952), 8; Robinson, “Betrayal of a Nation,” 156.

35 Roy C. Stiles and Albert Lyman, “The Administration of Justice in Korea under the Japanese and in South Korea under the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea to August 15, 1948,” paper by American Advisory Staff, Department of Justice, RDS, Korea, file 895; “Joint Korean-American Conference,” October 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 26; Gayn, Japan Diary, 423.

36 “South Korea: A Police State?” February 16, 1948, RDS, Division of Research for Far East Reports, 1946–1952, box 3.

37 Larsen, “Police and Public Security,” 60.

38 “A History of the Korean National Police (KNP),” August 7, 1948, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; “Let Us Avenge the Victims of Kwangju,” People’s Committee pamphlet. August 25,1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; Cumings, Origins of the Korean War, 1:364–66, 550.

39 George E. Ogle, South Korea: Dissent within the Economic Miracle (London: Zed Books, 1990), 12; Henderson, Korea, 147; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:356–57. At Yongchon, 350 kilometers from Seoul, a mob of ten thousand disarmed and kidnapped forty policemen after ambushing the police station and burned the homes of rightists.

40 John R. Hodge to Douglas MacArthur, SCAP, April 17, 1948; Police Diary, Major Albert Brown, Survey, October 1946, USAFIK, Okinawa, box 26; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” July 1947, GHQ-SCAP, 34; Henderson, Korea, 146; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 1:357. Henderson notes that not one identifiable North Korean agent was involved in the protests, which leftists claimed exceeded anything that had taken place under the Japanese.

41 “Summation of Non-Military Activities,” February 1948, GHQ-SCAP, 182; Richard J. Johnston, “Political Jailing in Korea Denied: Authorities Say 17,867 Held Are Accused of Theft, Riot, Murder and Other Crimes,” New York Times, November 26, 1947; Richard J. Johnston, “Seoul Aids Police in Checking Reds,” New York Times, September 6, 1949; Richard J. Johnston, “Korean Reds Fight Police and Others,” New York Times, July 29, 1947;“Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” September 1946, GHQ-SCAP, 22; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” December 1947, GHQ-SCAP, 165; Henderson, Korea, 167; Maglin, “Looking Back in History,” 69.

42 “History of the Police Department” and “Investigation of the Police,” July 30, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 25; “Visit to Wanju Jail,” August 1, 1946, USAFIK Okinawa, box 27, folder 1; “Sanitary Inspection of Jails,” USAFIK Okinawa, box 26, folder 4; Gayn, Japan Diary, 406, 407; Robinson, “Betrayal of a Nation,” 152.

43 Major General W. F. Dean to Lt. Commander John R. Hodge, “Review by the Departmentof Justice of Persons Confined to Prisons or Police Jails Who Might Be Considered Political Prisoners,” April 5, 1948, USAFIK, Records of the General Headquarters, Far EastCommand, General Correspondences (1943–1946), AI 1370, box 1.

44 “Summation of Non-Military Activities,” April 1948, GHQ-SCAP, 170; “Summation of Non-Military Activities in Korea,” July 1947, GHQ-SCAP, 22.

45 “Summation of Non-Military Activities,” January 1948, GHQ-SCAP, 181; “Report of Daily Police Activities,” USAFIK Okinawa, box 27, folder Civil Police; “Summationof Non-Military Activities in Korea,” August 1947, GHQ-SCAP, 196; Larsen, “Police and Public Security,” 133, 145; Bertrand M. Roehner, “Relations between Allied Forces and the Population of Korea,” Working Report, Institute for Theoretical and High Energy Physics, University of Paris, 2010, 168.

46 Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2:252.

47 Cumings, The Korean War, 122; Millett, “Captain James R. Hausman and the Formation of the Korean Army,” 503.

48 “Cheju-do: Summation of Non-Military Activities,” June 1948, GHQ-SCAP, 160; Merrill, Korea, 66.

49 “Field Report, Mission to Korea, U.S. Military Advisory Group to ROK,” RG 469, Mission to Korea, U.S. Military Advisory Group to the ROK, Records Related to the KNP (1948–1961) (hereafter KNP), box 4, folder Cheju-do; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2:250–59; Merrill, Korea, 125. My thanks to Cheju-do native Sinae Hyun for providing me with a clearer understanding of the internal dynamics fueling the violence during this period. After the massacre, the U.S. military command oversaw an increased police presence and stepped up local training efforts at the Cheju-do police school, which they financed. William F. Dean to Director of National Police, July 30, 1948, USAFIK Okinawa,box 26, folder Cheju-do.

50 Merrill, Korea, 113; Time, November 14, 1948, 6.

51 “Award of UN Service Medal to the National Police, Mission to Korea, Office of Government Services, Senior Adviser to KNP,” February 10, 1954, PSD, GHQ-SCAP (1955–1957), box 1, folder Awards and Decorations; “Policy Research Study: Internal Warfare and the Security of the Underdeveloped States,” November 20, 1961, JFKL, POF, box 98; Kim, The Unending Korean War, 122; Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA (NewYork: Doubleday, 2007), 56, 57.

52 Charles J. Hanley and Jae-Soon Chang, “Summer of Terror: At Least 100,000 Said Executed by Korean Ally of US in 1950,” Japan Focus, July 23, 2008.

53 James Cameron, Point of Departure (London: Oriel Press, 1978), 131–32; McDonald, Korea, 42; also Nichol, How Many Times Can I Die, 128. CIC agent Donald Nichol, a confidant of Rhee, reported that he stood by helplessly in Suwan as “the condemned were hastily pushed into line along the edge of the newly opened grave. They were quickly shot in the head and pushed in the grave. . . . I tried to stop this from happening, however, I gave up when I saw I was wasting my time” (ibid.)

54 Hanley and Chang, “Summer of Terror”; Bruce Cumings, “The South Korean Massacre at Taejon: New Evidence on U.S. Responsibility and Cover-Up,” Japan Focus, July23, 2008; Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 25; Kim, The Unending Korean War; Halliday and Cumings, Korea; Charles J. Hanley, Sang-Hun Choe, and Martha Mendoza, The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare fromthe Korean War (New York: Holt, 2000).

55 On U.S. strategic designs in Southeast Asia, see Chalmers Johnson, Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire (New York: Henry Holt, 2000); Gabriel Kolko, Confronting the Third World: United States Foreign Policy, 1945–1980 (New York: Pantheon,1990); John W. Dower, “Occupied Japan and the American Lake, 1945–1950,” in America’s Asia: Dissenting Essays on Asian-American Relations, ed. Edward Friedman and MarkSelden (New York: Vintage Books, 1971), 186–207.

56 Colonel Albert Haney, “OCB Report Pursuant to NSC Action 1290-d,” August 5,1955, DDEL, OCB, box 17, folder Internal Security; “Analysis of Internal Security Situationin ROK Pursuant to Recommended Action for 1290-d,” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957, pt. 2, Korea, ed. Louis Smith (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1993), 183.

57 “Bandit Activity Report,” May 1, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 4; Park Byong Bae, Chief, Security Division, “Operation Report,” July 1, 1954, and “Periodic Operations Report,” May 27, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 4; “Results of Police Operations,” July 15, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 2; “Summary of NSC Action 1290-d Report on Korea,” DDEL, OCB, box 17, folder Internal Security.

58 “G-2 Section Report,” February 2, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 4.

59 “Quarterly Historical Report,” July 10, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 4; also “G-2 Section Report,” March 25; May 2, 1954.

60 “Johnny” to Police Adviser, “Bandit Activity Report,” May 1, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 4.

61 “Police Wipe Out Last Known Guerrilla Band and “Red Bandit Chief Slain, TwoKilled,” Korea Times, December 1956, NA.

62 Henderson, Korea, 173.

63 William Maxfield to Director, NP [National Police], ROK, February 16, 1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 1; Gregg Brazinsky, Nation Building in South Korea: Koreans, Americans ,and the Making of a Democracy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 28–30; Report of an Amnesty International Mission to the Republic of Korea, March 27–April 9, 1975 (London: Amnesty International, 1977), 29; William J. Lederer, A Nation of Sheep(New York: Norton, 1961), 79; “Combined Korean Communities in USA Picket White House to Protest Carnage of Korean Youth,” April 22, 1960, DDEL, OCB, White House Office, Central Files, General File, Korea, box 821; Peer De Silva, Sub Rosa: The CIA and theUses of Intelligence (New York: Times Books, 1978), 163.

64 “Solon Alleges Police Attack,” Korea Times, October 26, 1956; “Captain Warren S. Olin: Chungmu Distinguished Military Service Medal with Silver Star,” March 1, 1955, Republic of Korea, courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, St. Louis; see also “Culprit Charges Police Plotted Murder,” Korea Times, December 15, 1956; “May 5 Riot Nets Prison Term for 14,” Korea Times, May 14, 1956. A Pacific war veteran from New Jersey, Olin went on to head the army’s Criminal Investigation Branch in Vietnam.

65 Kim, The Unending Korean War, 201–2; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2:265. For eight months in 1947, Kim was Chang Taek-sang’s personal bodyguard.

66 Muccio, quoted in Cumings, The Korean War, 183. One document preserved at the National Archives which points to the close symbiotic relationship between U.S. advisers and General Kim was a letter from Colonel Joseph Pettet of the Public Safety Branch thanking him for “the wonderful party you gave us on October 29, 1954. The food and entertainment was superb as always at a ‘Tiger’ Kim party.” Joseph Pettet to Chief Kim, November 1,1954, KNP (1953–1955), box 1.