Can Japanese Agriculture Overcome Dependence and Decline?

Yukie Yoshikawa

Agriculture in Japan suffers from a wide range of problems, including a low food self-sufficiency rate of only 41%1 and an inflexible farmland market. Rather than seriously tackling these problems, the Japanese government has chosen to compensate farmers through import restrictions, subsidies and price supports.2 These measures, aimed at addressing the widening urban-rural income gap and assuring the Liberal Democratic Party’s rural base, raised Japanese rice prices to among the highest in the world and further reduced food self-sufficiency. Japan’s farm support initiatives began in the 1960s and were promoted by Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei as “Nihon Rettō Kaizō Ron” (Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago). The large infrastructure projects launched under this program provided public works jobs in rural and urban areas that boosted incomes of rural communities but did little to stay the decline of agriculture.

Moreover, international pressure to open Japan’s agricultural markets increased, most strikingly during the Uruguay Round Agreement in 1994. Japanese policies of protecting farmers through maintaining high market prices and high tariffs were targeted, and Japan was forced to accept food imports at the level imposed by the World Trade Organization (WTO), in return for keeping high tariffs on rice and other products. This has not helped Japan’s agriculture, however, because the government simply chose to delay the drastic changes necessary to enhance the competitiveness of Japanese farmers. Meanwhile international demands for free trade continued to increase.

A chance for a drastic shift in Japan’s agricultural policy came in 2009, when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) ousted the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from power. The DPJ has proposed a new agricultural policy that would facilitate opening of Japan’s agricultural market while compensating farmers with direct subsidies. But will the DPJ’s policy work, and how well will it serve Japanese agriculture? This article compares LDP and DPJ policies, and assesses the future prospects for agriculture.

I. Problems of Japanese Agriculture

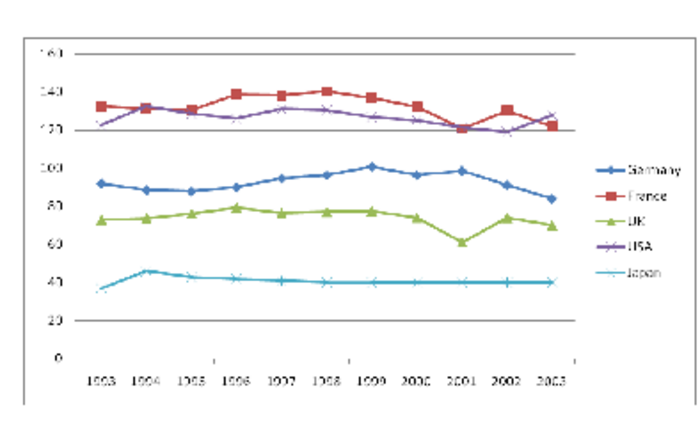

As Figure 1 shows, Japan has the lowest rate of food self-sufficiency of developed countries.

Figure 1: Food Self-Sufficiency Rate Comparisons

Source: Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishery (MAFF) website.

Note: Food self-sufficiency rate = domestic food production (including for export)/ domestic food consumption.

Japan’s low rate of food self-sufficiency is principally due to the fact that farm size is so small that it is almost impossible to make a living by farming. The result has been a decline in the number of farmers, the aging of the agricultural population, and a drop in the amount of land under cultivation. The population of those who primarily engage in farming sharply declined from 11.8 million in 1960 to only 1.9 million in 2009, with 61% being 65 years of age or older. Revenue from farming amounted to only a quarter of farmers’ total revenue in 2007. Agriculture accounted for just 0.8% of GDP in 2007. And total farmland shrunk by nearly a quarter from 609 hectares (ha) in 1961 at its height to 463 ha in 2008.3

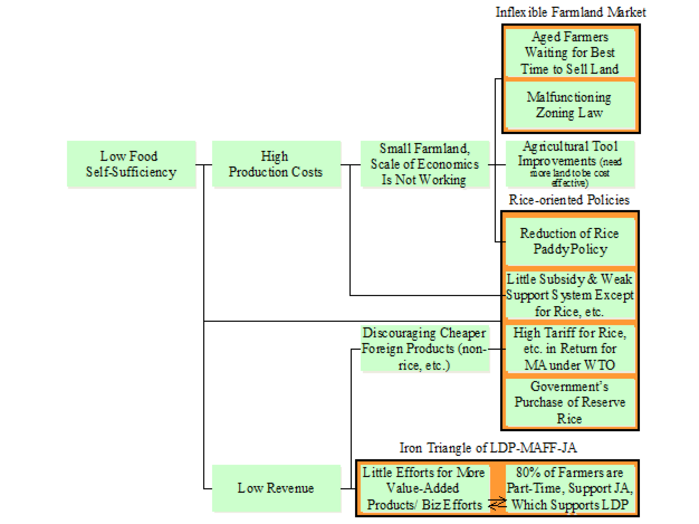

As shown in Figure 2, Japanese agriculture suffers from an inflexible farmland market, rice-oriented government policies, and the part-time farming cycle. We examine each of these problems below.

Figure 2: Root Causes of Japan’s Low Food Self-Sufficiency Rate

Inflexible Farmland Market

There are four main factors behind the low self-sufficiency rate: high production costs, low revenue (i.e., sales), government policy failures, and the combination of high market price for rice with high entry barriers. The high production costs are in part a product of inefficiencies associated with small-scale farming. Indeed, in 2009 the average farmland per farmer was only 1.41 ha, except in Hokkaidō4 (where it was 20.5 ha).5 While today in Japan 10 ha or more is said to be the optimal farmland size for full-time agriculture,6 only 0.7% of Japanese farmers have land this size. The vast majority—92%—have 3 ha or less;7 this has not changed much since the 1947 Land Reform which created a structure in which 99% of Japanese farmers owned land of this size, one considered optimal for farmers at that time. Due to technological improvements leading to rising cost in agricultural tools and machines, more revenue, or land, is required to cover costs. But while the minimum size of farmland to make living has increased by more than 300% in 60 years, the farmland per farm household has not expanded.

Why are Japanese farmers having a hard time expanding their farmlands? The two major reasons are the inflexible farmland market and the government policy of reducing the amount of land cultivated as rice paddies (gentan). In addition, the majority of farmers are already at the retirement age of 65 or older, with few successors.8 According to government statistics, 390,000 ha of farmland was abandoned (not farmed but still owned by an(ex-)farmer household) in 2005,9 though the actual number is probably higher, as farmers often deny abandoning land in order to receive various incentives and to avoid higher land taxes, as the real estate tax law favors farmland. Yet few younger Japanese farmers can buy the abandoned land.

Why? It is because of the irony that “farmland itself, not crops, is the most profitable output in Japanese agriculture.”10 Farmers can expect their land to be sold at extraordinarily high prices when the government builds roads, airports and other public facilities or when discount stores and other companies buy their land. Good farmland is flat, sunny, and square, with good access to roads and water. These also happen to be good conditions for big shopping centers and factories.11

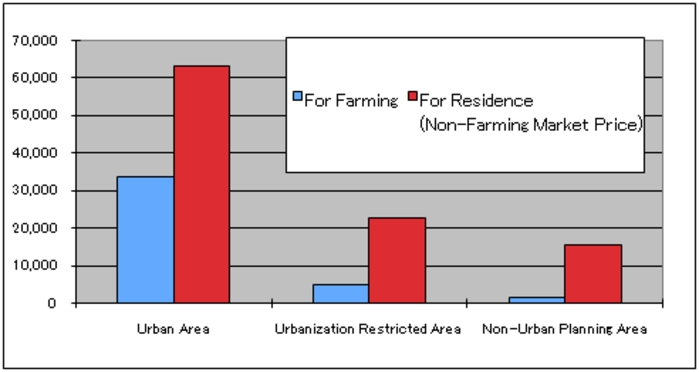

Thus, it makes sense for farmers, especially those with good farmland, to wait for such offers rather than to sell their land to fellow farmers who cannot pay as much, as shown in Figure 3. Landowners are even reluctant to lease land to other farmers, for fear that the renters could demand a portion of the profit if the land is sold. And farmers know the best way to foster windfall offers: pressure local politicians. Indeed, the best scenario for Japanese farmers is, first, keep the farmland, whether they are actually farming or not, in order to receive various agricultural subsidies and enjoy a low tax rate; second, pressure local politicians to start public works projects or to promote shopping centers so that they can sell their farmland at premium prices; third, when the projects are approved, remove their land’s status as farmland to facilitate its sale;12 and fourth, sell it.

Figure 3: Wide Price Gaps in Land Sales by Purpose, National Average

(Unit: 1,000 yen per 10 a)

Source: Zenkoku Nōgyō Kaigisho (National Chamber of Agriculture), Denpata Baibai Kakaku tō ni Kansuru Chōsa [Survey on the Sales Prices of Farmland etc.], FY 2007 edition, (Tokyo: National Chamber of Agriculture, Fall 2008).

For this strategy to work, farmers need weakly enforced zoning regulations. As noted by Yamashita Kazuhito, an ex-MAFF official, although Japan has two related laws designed to prevent the reduction of farmland, they have not functioned effectively.13 The Local Agricultural Committee (LAC), which is elected by farmers and represents the voice of local farmers, investigates and gives opinions on whether a tract of farmland should be re-designated to allow its use for other purposes. The local officials listen to the Committee, and then make the final decisions.14 Considering that local farmers elect these officials, it is hard to ignore their opinions, and collusion prevails between the Committee and potential sellers of farmland, who typically are both longstanding members of the same community.15

Indeed, in 2006, 13,413 ha of farmland was re-designated, of which 55.9% became roads, railways, public facilities (including hospitals, and industrial, commercial use) and service facilities. As much as 49–55% of the re-designated farmland has undergone such re-designation yearly since 1986,16 when land prices, especially in cities and neighboring areas, skyrocketed along with the bubble economy. While the MAFF statistics show that the amount of farmland re-designated for other purposes in 2006 was half of the amount at the peak in 1991,17 Prof. Gōdō Yoshihisa warns that the statistics do not include illegal re-designation and re-designation after abandonment, He estimates that this re-designation increased 1.5 times from 1994–2003 and 1.4 times from 1995–2000. This implies that the total shifting area of re-designated land has actually increased, not declined.18

The MAFF has been trying to tackle the inflexible farmland market by promoting leasing. The revision of the Agricultural Land Act in 1970 and the projects to promote effective usage of farmland in 1975 bade farewell to the owner-farmer principle of land reform, and allowed leasing if supported by the LAC.19 Despite similar efforts made since then, the rented land area grew only to 448,481 ha in 2005,20 slightly more than the 390,000 ha of farmland abandoned in the same year, and less than the amount of abandoned farmland during 2007–2009.21 Despite revision of laws to favor landowners, renters can still refuse to leave unless given money as compensation. Thus, farmers with good land are reluctant to lease their lands.22

Rice-Oriented Policies

The second main reason why full-time farmers are having trouble expanding their farmland is the government’s gentan policy of reducing the amount of land cultivated as rice paddies. To date, the gentan policy has reduced rice paddies by 1.1 million ha. Introduced in 1969, the policy is intended to keep the price of rice high by reducing the rice supply. All farmers, with the exceptions of those in the few regions that did not accept the gentan policy,23 are required to shift part of their rice paddies to other crops according to the size of the rice paddy (the larger the paddy, the more production has to be shifted). The MAFF spends 200 billion yen annually to compensate 2 million farm households. But this policy does not make sense, because it encourages farmers with smaller tracts of farmland to hold onto their land thus preventing consolidation of farmland into more economically viable farms. For the LDP, asking small farmers to abandon their farmland was tantamount to political suicide, as these farmers constituted its loyal power-base in rural regions that have been disproportionately represented in the Diet.24 Gentan, which was primarily a political program aimed at shoring up a local constituency, has prevented rationalization of land use and kept farms inefficient.

In the late 1950s, due to the growing income gap between urban laborers and rural farmers, the government took control of rice production and distribution, buying all rice crops at a high price and selling them at a cheaper price. This policy obviously resulted in losses for the government, while providing incentive for farmers to harvest as much rice as possible. Finally, in 1969 the LDP gave up this costly policy. By then, the revenue gap between city and rural dwellers had significantly declined.25

The gentan policy also allowed interim dealers to trade rice freely, bypassing the Food Agency. This too benefited rice farmers, because the farmers’ association, Japan Agriculture (JA), could sell rice more freely. The government control system, however, could not catch up with changing consumer demand, and an increasing amount of illegally traded rice (yami gome, or rice sold by anyone, including individual farmers, who bypassed JA) came to the market. Finally, in 1995, the LDP abandoned the rice control system completely, allowing anyone to sell rice (legalizing yami gome) and to import rice under the Uruguay Round Agreement. In 2003, the government limited its purchases of rice to reserve purposes.26 Of course, such purchases are still a form of intervention to absorb the oversupply of rice in the consumer market. But the impact is much smaller than during the days of full governmental control. Today, the gentan policy, besides high tariffs, is the primary means government uses to maintain high rice prices.27

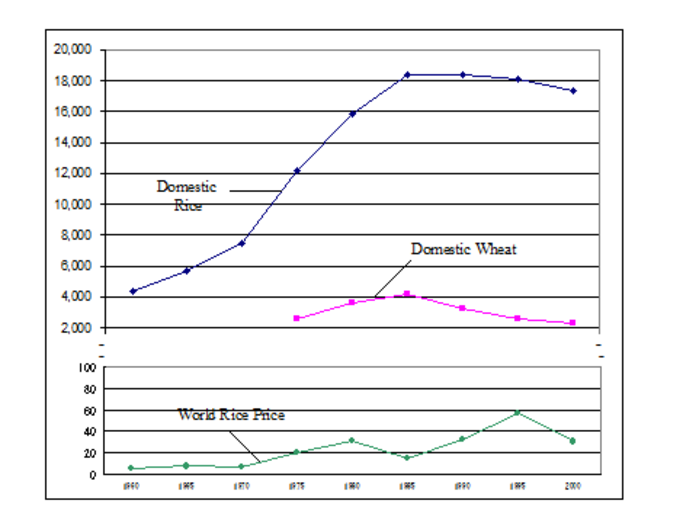

While rice farming has long enjoyed significant LDP support, other products, including wheat, beans, and cereals for cattle feed, are virtually ignored, and most of these products are imported. Despite the consistent increase in the consumption of bread and the decline in the consumption of rice (this “Westernization” of the Japanese diet is the MAFF’s official excuse for Japan’s low food self-sufficiency rate), no serious discussion was undertaken in the MAFF on increasing wheat production. The result was that the price of rice remained high, while the consumer wheat price (the sale price of the government to the milling companies) was kept low, as shown in Figure 4.28 Not surprisingly, Japan’s high priced rice surplus grew while the nation grew ever more dependent on the import of wheat and other grains.

Figure 4: High Rice Price, Low Wheat Price

(Unit: yen/ 60Kg)

Note: The prices refer to the sales prices of the government to private distributors.

Source: MAFF, Shokuryō Tōkei Nenpō [Food Statistical Yearbook], 2005 edition; International Rice Research Institute website; World Bank, World Development Indicators Online.

Partly as a result of price disparities, rice consumption continued to decrease from 13.4 million tons at its peak in 1963 to 8.7 million tons in 2008, while wheat consumption grew from 6 million tons in 1960 to 8.5 million tons in 2008,29 as shown in Figure 5.30

Figure 5: Comparison of Rice and Wheat Production and Consumption

(Unit: 1,000t)

Source: MAFF website.

The LDP stubbornly protected rice from foreign competition, in return for surrendering most other items. At the Uruguay Round Agreement in 1995, the Japanese government accepted importing from 4% (1995) to 8% (2000) of domestic rice for consumption according to the minimum access requirement, in return for not opening the rice market (no private entity was allowed to import foreign rice). In contrast, all other products whose trade the government had full control over (no private entity was allowed to import them) were allowed on the open market. In 1999, Japan agreed to open the rice market, in exchange for reducing the import quota to 7.2%.31 Yet, the rice tariff (778%) is extremely high. By comparison, the average tariff of agricultural products is 12%.32 Some crops with low self-sufficiency rates also have high tariffs, including wheat (252%), barley (256%), and red beans (403%).33 Yet rice enjoys more robust protection.

As a result of these rice-oriented policies, Japan’s food self-sufficiency rate today is 100% for rice, 14% for wheat, 26% for cereals for feed, and 9% for beans.34

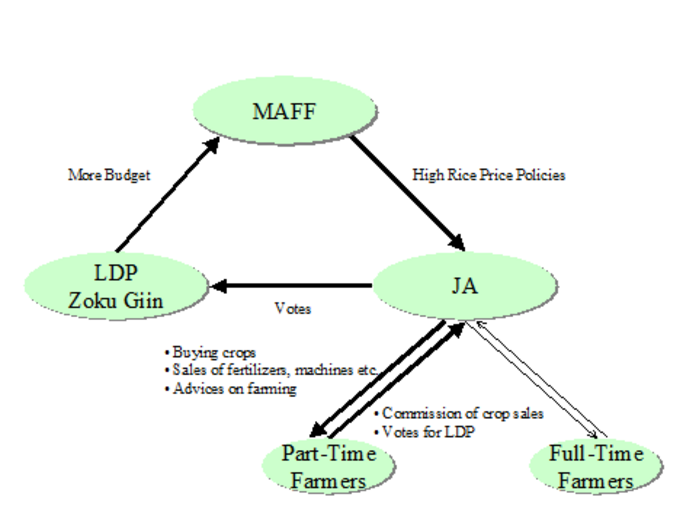

Iron Triangle of LDP-MAFF-JA

Then why does the LDP go to all this trouble to focus on rice? We can find the answer in the structural collusion among the LDP, MAFF and JA, as shown in Figure II-6.

Figure 6: Iron Triangle of Collusion of LDP-MAFF-JA

Note 1: This figure is based on Yamashita Kazuhito, “Minshutō no Manifesuto no Mondai [Problems of the DPJ Manifesto]”, August 20, 2009, Tokyo Foundation website.

Note 2: The lighter lines of Full-Time Farmers with JA show weaker link than those of Part-Time Farmers.

For most farmers, lacking economies of scale, farming is not sufficient to make a living, forcing 80% of farmers to work part-time.35 This discourages younger generations to succeed as farmers and invest their time to become successful farmers, including analyzing the market, producing value-added products, promoting their products, and expanding their sales networks. Instead, they look to the JA, which advises them about how much to plant, water and fertilize, sells/rents them all kinds of agricultural equipment, sells them fertilizer and seeds, and buys agricultural products from them. For JA, the commission it gets from sales of these products and crops is significant. Thus, JA has a strong incentive to keep the rice price high so that their sales commissions also will be high.36

In order to maximize its profit, JA approaches local politicians, namely the LDP Diet members who have close connections with the MAFF, also known as Nōrin-zoku, asking them to pressure the MAFF to keep the rice price high. The LDP Nōrin-zoku happily do so in return for the farmers’ votes. The MAFF in return receives larger budgets.37

II. LDP Agricultural Policies

What has MAFF done so far to tackle these problems? Below we will discuss the three most important issues: farmland reform, rice-oriented policies, and the LDP-MAFF-JA Iron Triangle.

Farmland Reform

As we have seen, the root problem of Japan’s agriculture lies in the inflexible farmland market, which forces most farmers to be part-timers who end up supporting the JA and the LDP, who in return enforce policies to keep the price of rice high. Full-time farmers must be able to obtain or rent more farmland in order to have enough land to make economic sense, meaning that a majority of current part-time farmers need to be encouraged to sell or leasetheir lands. Farmers can only achieve economies of scale and increase productivity through consolidation of landholdings at least to the extent thatthey can make a living by farming.

Unfortunately, LDP administrations never addressed this issue. Given that part-time farmers who want to sell their land at high prices for non-farm uses represent a key constituency for the LDP, the party balked at reforms aimed at consolidating farm holdings. In addition, the JA facilitates such profitable non-farm use land transactions because the cash from the sales are deposited in JA bank accounts. In this context, it has been difficult for the MAFF to strictly enforce zoning laws that would curtail the lucrative practice of re-designating farmland for non-farm use. The most the ministry can do is facilitate land leasing, especially of abandoned land, and encourage cultivating twice a year and harvesting different crops from the same farmland. The New Agriculture Policy 2008 mentioned that the ministry would eradicate abandoned land by 2011.38

Changing Tactics of Rice-Oriented Policies: Introducing Direct Subsidy

The government has mostly ignored the cost of its rice-oriented policies: instead of ending these policies including gentan, which encouraged farmers to produce more rice than Japan could consume, it desperately sought to expand domestic consumption of rice. For example, it shot TV commercials encouraging people to eat rice for breakfast (mezamashi gohan campaign); encouraged local consumption of local products (chisan chishō); urged using rice powder (komeko) in bread and pasta and producing rice for feeding cattle; and promoted exports of Japanese agricultural products. In order to reduce production costs, it also supported eco-feeding (feeding cattle leftover food) and using rice straw for fuel.39

The only significant exception is the policy change that came with the international pressure of the WTO’s Doha Round negotiations to comply with authorized policies to support farmers (sticking with unauthorized policies brought penalties, including a high mandatory ratio of minimum access imports). In 2007, the MAFF started a new direct subsidy system (Hinmoku Ōdanteki Keiei Antei Seisaku) that would comply with the WTO. This system provides two kinds of subsidies. One is aimed at compensating for the gap in production costs compared with those of the primary source of Japan’s imports, the United States, for four products: wheat, soybeans, sugar beets, and potato to produce starch. The other provides revenue for farmers producing rice, wheat, soybeans, sugar beets, and potato to produce starch in case of poor harvests due to bad weather or price plunges. Further, only farmers and farming organizations with 4 ha or more (10 ha or more in Hokkaidō) were entitled to the subsidies40 in order to encourage the concentration of farmland among large-scale farmers.

However, this LDP policy proved to be unpopular. The DPJ victory in the Upper House election in 2007 was partly due to its proposal for another direct subsidy system (Kobetsu Shotoku Hoshō Seido). This one targeted more farmers (there were no conditions on farmland size) with a generous budget of 1 trillion yen, compared with 142 billion yen budget41 for the MAFF’s new direct subsidy system in 2007.42 Soon, the LDP loosened the strict condition on farm size for eligibility to participate in the Hinmoku Ōdanteki Keiei Antei Seisaku system so that smaller-sized farmers could benefit if authorized by local government,43 and the budget was increased to 224 billion yen in 2008.44 But this new policy was doomed with the LDP’s loss in the 2009 Lower House election, which also had more significant consequences, as we discuss below.

III. DPJ Agricultural Policies

A Fatal Blow to the LDP-MAFF-JA Iron Triangle: The DPJ’s New Agricultural Policy

The iron triangle of the LDP, MAFF, and JA seemed to be robust enough to last forever. However, one element, the LDP, crumbled with its great loss in the general election of August 2009. The new DPJ administration succeeded in defeating the LDP in rural areas, which had been its traditional power base, partly by proposing Kobetsu Shotoku Hoshō Seido [System to Compensate Farming Households].

Kobetsu Shotoku Hoshō Seido is intended to encourage Japanese farmers to cultivate agricultural products whose production costs are higher than their prices, including rice and wheat, and to invest more in agriculture in order to improve quality and aid other business efforts. By guaranteeing to pay the difference between the cost of production and market prices, the system encourages farmers to plant crops other than rice. Furthermore, by providing incentives for farmers to produce according to the government’s production plan, the policy could contribute to a higher food self-sufficiency rate.45 Farmers can even sell their products at prices that can compete with their foreign counterparts. (This is why the DPJ initially proposed to sign a long-debated Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the United States. Subsequently, it backed away from this bold proposal, instead merely proposing that Japan “expedite FTA negotiations,” fearing a voter backlash in the August 2009 election.) The shift from price support to direct subsidy is acceptable to farmers who do not care whether their revenue comes from a high price of rice or from a direct subsidy, as long as their income is assured. It is only the JA that wants to keep the price of rice high.46

Of course, there was an underlying factor in the crumbling of the triangle: JA has been losing power. Gōmon posits the following reasons: 1) declining profit in its financial sector, which has been its major revenue source; 2) the electoral reform of 1994, which narrowed the electoral district voting disparity between city dwellers and rural people; 3) liberalization of the agricultural products distribution system (legalizing yami gome) where JA played a dominant role; 4) an increase in criticism of public works in rural areas, making it difficult for JA to bring in such projects; and 5) the shrinking farming population undermined its political power.47

Further, farmers are not always happy with JA and its inefficient practices. They are frustrated about its fertilizers and other agricultural materials that are more expensive than those in garden stores, partly because JA has to provide such merchandise in remote regions at the same price as more central areas, and these costs had to be shared among all farmers. Farmers also complain about JA’s low purchasing prices for their crops, which do not allow them to make a living by farming alone. Thus, in 1992 when the farmers association (nōkyō) renamed itself JA, a satire was heard: “JA sayonara” (“ja” can mean “good bye” in Japanese.)48 Thus, if there was an attractive alternative to JA, many farmers would welcome it.

Therefore, the DPJ appealed directly to the farmers, while damaging JA, which it saw as just a power broker for the LDP. The subsidies would bypass JA and provide direct government to support to farmers.

Prospects for DPJ Agricultural Policy

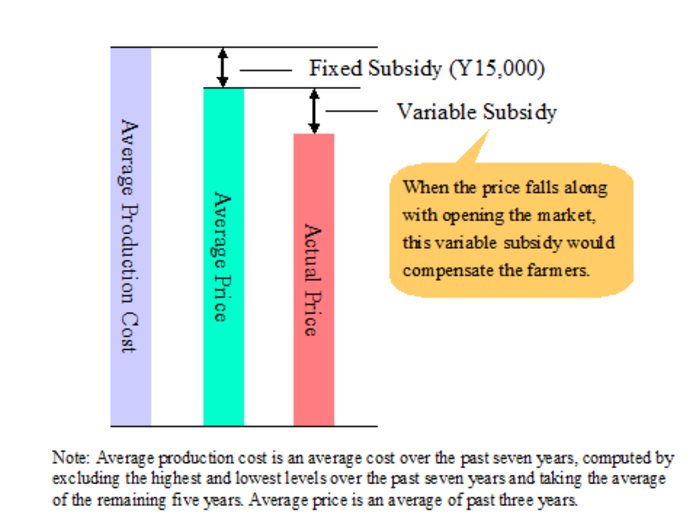

It is too early to evaluate the DPJ’s proposed policy.Little is really known about it other than what is in MAFF’s FY2010 budget, which the Hatoyama cabinet approved on Christmas Day of 2009. But the budget suggests that the largest change will be in the rice-oriented policies, namely the DPJ’s direct subsidy system. There will be a transitional budget (562 billion yen) before full introduction of Kobetsu Shotoku HoshōSeido in 2011.

In FY2010, the government will introduce Kobetsu Shotoku HoshōSeido for rice as a model case, and another direct subsidy system to farmers who cultivate crops with low self-sufficiency rates including wheat (Suiden Rikatsuyō Jikyūritsu Kōjō Jigyō). Kobetsu Shotoku HoshōSeido for rice would provide a direct subsidy of 15,000 yen per 10 ares (a)49 (the average gap between the rice price and the production cost), as well as for the gap between the actual price and average price, as shown in Figure 7. The subsidy would go to rice farmers who consent to produce according to the production plan agreed upon with the government. In return, the gentan policy was quietly removed from MAFF’s budget document for FY 2010.50 This farewell to the gentan policy seems to be a big step forward in rectifying the distorted demand-supply relationship and undermining the JA stranglehold on the farming sector.

Figure 7: DPJ’s Direct Subsidy System on Rice

Note: Drafted by Yukie Yoshikawa based on MAFF, Heisei 22 Nendo Nōrin Suisan Kankei Yosan no Shuyō Jikō [Major Points in the FY2010 Budget on Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery] MAFF website

Suiden Rikatsuyō Jikyūritsu Kōjō Jigyō would provide direct subsidies to farmers who cultivate wheat, barley, soybean, feed cereals (35,000 yen/10 a), or rice for energy or feed (80,000 yen/10 a), or who cultivate buckwheat or rapeseed (20,000 yen/10 a).51 The DPJ expects that, by subsidizing these crops, farmers can earn as much as rice farmers while boosting food self-sufficiency.

At least theoretically, these policies appear promising, as 1) they would encourage rice farmers to have larger fields and improve productivity; 2) without the gentan policy which limited production of rice, the rice price would decline; and 3) encouragement to produce crops other than rice would enhance the national food self-sufficiency rate. Farmers could profit more by lowering actual costs below the average cost that the Kobetsu Shotoku HoshōSeido policy assumes, and the easiest way to do so would likely be through achieving economies of scale, namely procuring more farmland. Although the fixed amount of the subsidies does not seem likely to raise productivity, if a farmer sells surplus rice beyond the amount initially planned as rice for cattle-feeding, he/she can increase profit by receiving subsidies from both Kobetsu Shotoku HoshōSeido and Suiden Rikatsuyō Jikyūritsu Kōjō Jigyō.

Yamashita Kazuhito, however, questions these merits. He argues that the DPJ plan is not intended to increase productivity. Rather, like the gentan policy, he argues that it is intended to decrease rice production as the DPJ plans to give subsidies for “reducing production to 6 tons of rice for farmers who can produce 10 tons.”52

Moreover, the DPJ policies do not address effectively the need to expand the amount of farmland under cultivation, do not promote consolidation of landholdings and do not tighten enforcement of zoning restrictions. Rather, part-time farmers would be assured of receiving the same revenue from the direct subsidy as before, and thus small-scale farmers will choose to continue farming rather than sell their farmland. Nor do the new policies help full-time farmers acquire more farmland.53 This policy may help the DPJ woo small-scale farmers away from the LDP, but it will not promote significant agricultural reform. Other than the changes mentioned above, the DPJ proposal does not represent much improvement on LDP policies, although it does subsidize the cost of reviving abandoned land into productive farmland.54

Thus, DPJ policy may lead to somewhat lower rice prices, while lowering rice production through its new direct subsidy system and facilitating the opening of Japan’s agriculture market so that Japan can promote FTAs with the US and other countries, which Japanese business circles eagerly promote. This represents a wasted opportunity to initiate more sweeping and urgently needed farmland reforms.

Yukie Yoshikawa is a Senior Research Fellow at the Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies, School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), The Johns Hopkins University. She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Yukie Yoshikawa, “Can Japanese Agriculture Overcome Dependence and Decline?” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 26-3-10, June 28, 2010.

Notes

1 2008 figure. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishery, Japan (MAFF) website.

2 The Republic of Korea (ROK) followed Japan around the late 1980s. For example, in Japan the percentage of the national budget devoted to agriculture doubled agriculture’s portion of the GDP for the first time in the late 1960s, while in the ROK that happened in the 2000s. In China in the mid-1970s, Deng Xiaoping announced that China was entering the first stage of modernization under the slogan of the Four Modernizations, claiming that those who could get rich quickly (including in the coastal region, such as Shenzhen) should indeed get rich. Signs of the transition to the second stage in China are starting to show today. See Hara Takeshi and Waseda Daigaku Taiwan Kenkyūjo ed, Gurōbarizēshon-ka no Higashi Ajia no Nōgyō to Nōson: Nichi/ Chū/ Kan/ Tai no Hikaku [East Asian Agriculture and Rural Villages under Globalization: Comparison of Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan] (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 2008), 167; Chen Zhonghuan, Crisis of Chinese Agriculture and the Meaning of its Transition into Protection Policy (Tokyo: Hihyōsha, 2008), 3.

3 MAFF website.

4 The Japanese archipelagos except Hokkaidō are mountainous or hilly (73% of the total area has these features) and have few plains. Hokkaidō is regarded as exceptional. Thus, the figures used in this article exclude Hokkaidō, unless otherwise indicated.

5 The 2009 figure. MAFF website .

6 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 134.

7 MAFF, Farmland Census, 2005.

8 The 2009 figure. MAFF website.

9 MAFF website.

10 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 146.

11 Ibid, 131-4.

12 Ibid.

13 Yamashita Kazuhito, “Let Corporations Play a Role in Reviving Japanese Agriculture”, December 2, 2008, Tokyo Foundation website.

14 MAFF website.

15 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 138-9.

16 Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Bureau website. Links 1, 2.

17 Ibid.

18 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 147-8.

19 Ibid, 156-9.

20 MAFF, Farmland Census, 2005.

21 MAFF, “Kōchi Menseki [Farmland Areas], various years, MAFF website.

22 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 157-8.

23 Includes well-known expensive rice brand farmers in Uonuma city, Niigata.

24 Yamashita Kazuhito, “The Pros and Cons of Japan’s Rice Acreage-Reduction Policy”, October, 07, 2008, Tokyo Foundation website.

25 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 100-4.

26 Ibid.

27 Yamashita Kazuhito, “The Pros and Cons of Japan’s Rice Acreage-Reduction Policy”, October, 07, 2008, Tokyo Foundation website.

28 Yamashita Kazuhito, “Nihon no Shokuryō Jikyūritsu ha Naze Teika shitanoka [Why did Japan’s Food Self-Sufficiency Rate is so low?]”, August 27, 2008, Tokyo Foundation website.

32 Hara Takeshi and Waseda Daigaku Taiwan Kenkyūjo ed, Gurōbarizēshon-ka no Higashi Ajia no Nōgyō to Nōson: Nichi/ Chū/ Kan/ Tai no Hikaku [East Asian Agriculture and Rural Villages under Globalization: Comparison of Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan] (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 2008), 51.

33 MAFF, “WTO Nōgyō Kōshō no Genjō [The Current Status of WTO Agricultural Negotiations]”, March, 2010, MAFF website, 3.

34 MAFF website.

35 2009 figure. MAFF website.

36 Yamashita Kazuhito, “Minshutō no Manifesuto no Mondai [Problems on the DPJ’s Manifesto]”, August 20, 2009, Tokyo Foundation website.

37 Yamashita Kazuhito, “Tokei no Hari wo 30nen Modoshita Jimintō Nōsei [The LDP Agricultural Policy that Made Japanese Agriculture Obsolete for 30 Years]”, July 9, 2009, Tokyo Foundation website.

38 MAFF, “21 Seiki Shin Nōsei 2008: Shokuryō Jijō no Henka ni Taiō shita Shokuryō no Antei Kyōkyū Taisei no Kakuritsu ni Mukete” [New Agricultural Policy 2008 in the 21st Century: Targeting a Stable Food Supply System in Align with Changes in Agriculture], May 7, 2008, MAFF website.

39 Ibid.

40 Hara Takeshi and Waseda Daigaku Taiwan Kenkyūjo ed, Gurōbarizēshon-ka no Higashi Ajia no Nōgyō to Nōson: Nichi/ Chū/ Kan/ Tai no Hikaku [East Asian Agriculture and Rural Villages under Globalization: Comparison of Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan] (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 2008), 59-74.

41 MAFF website.

42 According to the DPJ’s Nōgyōsha Kobetsu Shotoku Hoshō bill submitted to the Upper House in 2007, the DPJ estimated the cost as 1 trillion yen. Upper House, Nōgyōsha Kobetsu Shotoku Hoshō Hōan [Bill for Kobetsu Shotoku Hoshō to Farmers], Upper House website.

43 Hara Takeshi and Waseda Daigaku Taiwan Kenkyūjo ed, Gurōbarizēshon-ka no Higashi Ajia no Nōgyō to Nōson: Nichi/ Chū/ Kan/ Tai no Hikaku [East Asian Agriculture and Rural Villages under Globalization: Comparison of Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan] (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 2008), 95.

44 The MAFF renamed the policies Suiden/ Hatasaku Keiei Shotoku Antei Taisaku in 2008. The MAFF website.

45 DPJ, Minshutō Seisakushū INDEX 2009, DPJ website.

46 Yamashita Kazuhito, “Minshutō no Manifesuto no Mondai [Problems on the DPJ’s Manifesto]”, August 20, 2009, Tokyo Foundation website.

47 Gōdō Yoshihisa, Nihon no Shoku to Nō: Kiki no Honshitsu [Food and Agriculture in Japan: Core of Crisis] (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2006), 117-8.

48 Hara Takeshi. Nihon no Nōgyō [Japanese Agriculture] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1994), 40.

49 The subsidized area will be the total area minus 10 a, assuming the crop from the 10 a is consumed by the farmer’s family.

50 MAFF, “Heisei 22 Nendo Nōrin Suisan Kankei Yosan no Shuyō Jikō”, MAFF website.

51 MAFF, “Heisei 22nendo Nōrin Suisan Yosan Gaisan Yōkyū no Shūyō Jikō [Primary Agenda in Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Budget Request for FY2010]”, October 2009, MAFF website.

52 Yamashita Kazuhito, “Minshutō ha Nōsei Toraianguru wo Hōkai saseru [The DPJ will destroy the Agricultural Circle Triangle]”, July 22, 2009, Tokyo Foundation website.

53 Ibid.

54 MAFF, “Heisei 22nendo Nōrin Suisan Yosan Gaisan Yōkyū no Shūyō Jikō [Primary Agenda in Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Budget Request for FY2010]”, October 2009, MAFF website.