The Songs of Nippon, the Yamato Museum and the Inculcation of Japanese Nationalism

Yuki TANAKA

Si vis pacem para pacem

Over many years textbooks and conservative educational policies such as “moral education” have been central to the discussion of the propagation of Japanese nationalism. These are important facets of the persistent efforts to raise national sentiment. In recent years, however, new avenues for inculcating nationalism have emerged. This essay examines two such examples to gauge the role of popular culture in creating “love of nation” among children and youth.

The Songs of Nippon and Yasukuni Shrine

In April 2006, Yasukuni Shrine ran a music competition, inviting people to submit newly composed songs on the theme “Songs that make you love Japan,” as part of an event to commemorate “the end of the Great East Asian War.” Two hundred and thirty one songs were submitted in the three months before the closing date and six songs were ultimately selected by a panel of judges headed by musician Tsunoda Hiro. All six songs were written and sung by young amateur or semi-professional musicians, who are virtually unknown in Japanese music circles.

Tsunoda is a 58 year old singer, jazz drummer, and composer. In the early 1970s he played at famous jazz festivals in Montreuil and Newport as a member of one of Japan’s top jazz groups, the Watanabe Sadao Quartet. In 1971, his song Mary Jane became a big hit. However, his fame as a jazz musician quickly faded and subsequent efforts to form new bands all ended in failure. His recent songs express strong national sentiment.

Following the competition, Yasukuni Shrine produced a CD entitled Nippon no Uta (Songs of Japan), comprise of the above mentioned six songs, together with another song, written by Uchida Tomohiro, a relatively unknown writer of children’s songs, and arranged by Tsunoda. All the songs on the CD, except for one, composed and sung by a group called Arei Raise, are in the fashionable folk song style, characterized by a soft, slow melody, with sentimental, hackneyed phrases mingled with patriotic sentiments.

The following are extracts from some of these songs.

Spin your endless dream

Keep walking without looking back

Your heart is unshakable

Embrace your motherland

This is the nation to which you will always return

The land of Yamato, with its gentle breeze’

‘We are blessed with peaceful days

Thanks to those who endured harsh times

Those who had little food and water day after day

Yet kept a strong will and dreamt of a distant future

I pray for eternal peace and love

That is what I wish, sitting by this little stream of pure water

One of the songs entitled The Last Courage, by a group called Lily, does not include a single reference to Japan, the nation, or subjects which imply national sentiment. Instead it is a mélange of hackneyed phrases like these:

We live helping each other, connecting with each other

Dream, you, love and I

How long should we keep running

We do not realize even if we are running the wrong way

The more we struggle to live, the more happiness we gain

We don’t want to cry, therefore we believe in the last courage.

Riding on A Dragon, the song written by Uchida and arranged by Tsunoda, exudes Japanese sentiment, through evocation of the courage and sacrifice of the wartime generation:

No matter how times change, there are things that we must not lose

We will revitalize this nation that you loved so much

Atop a cherry tree where we aspire to be,

We find a blossom of our unchangeable oath

You protected this nation of eight islands with your own hands,

With endless dreams and ever-lasting love

Thank you for your dreams, Thank you for your love

We, too, will protect this golden country

Riding on a dragon, riding on a dragon.

Are not these songs too mediocre to attract the attention of young people and become big hits? Indeed, few copies seem to have been sold at the Yasukuni Shrine shop.

One exception is the song entitled Kyoji (Heroic Spirits), a rap song, by the group Arei Raise [Eirei Raise], comprised of three young boys. This group was formed when one of the boys saw a leaflet for the Yasukuni music competition shortly before the closing date. Indeed, they did not even have time to name their group before submitting their work. When their music was selected as one of the best pieces, Tsunoda named the group Arei Raise, a pun on a Japanese expression meaning “departed spirits of war heroes in the next world.”

Here is a full translation of Kyoji:

Even with those two atomic bombs

You could not burn down our nation, Sir

We overcame that disaster

Japan is great, after all

With few natural resources

With many descendants of talented people

Who overcame the human experiment with nuclear weapons

Let’s learn from the wisdom of our ancestors

With the full experience of the Sino-Japanese, Russo-Japanese, and Great East Asian Holy Wars

The experience of Edo, Meiji, Taisho, Showa and Heisei

This spirit of progress cannot be replaced by anything else

That is our unauthorized intangible cultural asset

Japan’s counterattack will soon be launched

First we must arm our hearts with nuclear arms

People always survive, thanks to the sacrifice of others

But the important thing is what we do with that sacrifice

It has been sixty years since the war ended

It’s now time to respect the spirits of war heroes and the end of the war

Japan’s war was noble and grand, whether it was right or wrong

To fight the enemy, knowing you would be defeated

To fight to win from time to time at the risk of your own life

Our ancestors were not wrong

We just love Japan

We are neither right nor left, we are simply bald headed

We like Japan and the Japanese a lot

Don’t forget our hopes and pride

For a start, raise your voices, you Japanese boys and girls

The spirit of Kamikaze is always with us

Let’s change the way people see “the typical Japanese”

With hip hop scenes

We really love this country

So we want to keep our hearts as gold as our nation is

We Japanese are strong minded, training ourselves day after day

Let’s make our song everlasting

We can get together here whenever we like

Our feelings echo each other

And become a rainbow under the sky of Yasukuni

There are things that we cannot do

Yet there are things that only we can do

Things that even we can do

Let’s keep singing until our voices grow hoarse

Don’t forget what we inherited from our ancestors

Keep them in mind all the time

And pass them on to the next generation

Let’s walk together towards our future

Nippon, A beautiful country

Nippon, The country where the sun rises

Nippon, A magnificent country

Nippon, Nippon, Nippon

Nippon, The country where gods live

Nippon, The country that we love so much

Nippon, Our country

Nippon, Nippon, Nippon

View and listen to it here

Listen here to their song Kudan (an allusion to Yasukuni Shrine) with photos of kamikaze pilots and texts of their letters home

This song, particularly the last phrase with the repeated words “Nippon” (“Japan”), is so jaunty and rhythmic that it could easily be chanted by a crowd of Japanese supporters at a World Football Cup match. In fact, chanting “Nippon” seems to be adopted from the actual football support group cheering at the World Cup games.

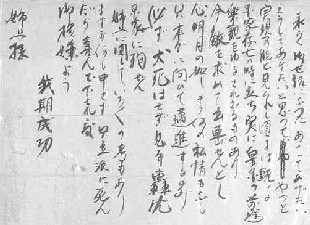

On August 15, 2007 – the 62nd anniversary of the end of the war – Arei Raise launched its first CD album, entitled Kyoji, using the title of its first song selected for the Yasukuni CD. This new CD contains eight rap songs including a rap version of the national anthem Kimigayo and the above-mentioned title track. One of the other songs, Kudan, bears the name of the district in Tokyo where Yasukuni Shrine is located. This song, dedicated to kamikaze pilots, uses extracts from the last letter sent home by a young Kamikaze pilot – ‘Dearest Father, Dearest Mother, the only regret I leave on this day is that I was unable to show you sufficient filial piety. I can’t thank you enough for giving birth to me and allowing me to live a fruitful 20 plus years.’

Kamikaze pilots prior to takeoff

Rap music is extremely popular among Japanese youth, as it is among young people in many parts of the world. Its historical origins – as an expression of rebellious sentiment by American black and Hispanic youth – have endeared it to some Japanese minority youth, particularly those of Ainu and Okinawan origin, who have begun to adopt rap and integrate it with their own ethnic melodies, thereby creating somewhat novel and appealing new music. One example is the band, Ainu Rebels, comprised of 16 Ainu youth who recently formed a band that promotes Ainu pride through rap performance.

This enthusiasm for imported styles is not shared by some Ainu elders, however, who fear the mixture of foreign music with their own may destroy the authenticity of Ainu culture. The leader of the Ainu Rebels, Sakai Mina, is the 24 year old daughter of Sakai Mamoru, who was active in organizing worker movements against the exploitation of day laborers in Sanya in the1980s, and died mysteriously in April 1988. His body was found floating in a canal near the Tokyo Bay.

Ainu rebels perform live at Alta Space

It is ironic, however, that rap is now eagerly adopted by groups like Arei Raise, which promote national sentiment and thus endorse the anti-minority policies adopted by Japanese state authorities. It is well recognized that the authorities continue to sanitize Japanese wartime atrocities not only against neighboring Asians but also against Japanese minority groups, as is evident, for example, from the recent text book affair regarding the compulsory group suicide of Okinawan citizens during the battle of Okinawa. There are, of course, those who think rap and hip hop music are an insult to the heroic Japanese spirits enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine. Regardless, it seems that songs by Arei Raise have a youth following – particularly among the so-called NEETs (Not in Education, Employment or Training). Indeed, the members of Arei Raise themselves belong to NEET. It is well known that some young NEETs seek identity through patriotism, as a means of regaining self-respect. Some, for example, are fans of nationalistic and xenophobic comics, such as those written by Kobayashi Yoshinori. There seems to be a similar phenomenon developing in the world of Japanese rap music as well.

It is also ironic that these patriotic NEET youths, who are themselves the victims of Japanese government policies of “economic restructuring and social reform” are unable to understand that young Kamikaze pilots – who were of a similar age at the time – were exploited by the military leaders and politicians of a government on the verge of collapse. If one reads carefully Kike Wadatsumi no Koe (Listen to the Voices from the Sea: Writings of Fallen Japanese Students), a collection of wills and letters written by young student soldiers including Kamikaze pilots, one can easily understand that Kamikaze pilots did not die for the “noble cause” of defending Japan.

Listen to the Voices from the Sea

Rather, through an indescribably painful psychological process, many sought justification for their forced suicide in an effort to defend their own beloved family members.

Letter from Kaiten pilot in Naval special forces

Some professional military pilots rejected the logic of the Kamikaze. Lieutenant Seki Yukio, a professional naval pilot, is a case in point. In October 1944, when ordered to carry out a suicidal mission by his senior officers, Seki told a colleague shortly before departure ‘We can no longer save Japan. It is a desperate measure that they have now decided to kill the best pilots like myself. I can drop a 500 kilogram bomb on the deck of an enemy aircraft carrier without killing myself’; ‘I am not going to die for the emperor, nor for Imperial Japan. I am going to carry out this mission for my beloved wife. I cannot refuse an order, so I will die to protect my wife. I will die for my beloved. Is that not splendid?’

In Usa city of Oita Prefecture, a Japanese restaurant called Tsukushi-Tei was frequented by many Kamikaze pilots before departing for their last missions. The columns and lintels of the Japanese rooms of this restaurant are full of marks of sword cuts that the young Kamikaze pilots made, heavily drunk and swinging around their swords. These marks convey the frustration experienced by these boys and the depths of bitterness at their forced self-annihilation. If any rap music is to be composed about Kamikaze pilots, it should convey the profound bitterness and anger of these youths. Undoubtedly, their anger, which they could not be clearly expressed in the political situation at the time, was directed at the military leaders and politicians who had little concern for the sacrifice of the lives of thousands of young men under the grand but meaningless justification of “defending the nation,” despite their clear knowledge of unavoidable defeat in the war in the very near future.

In addition to the music competition, Yasukuni Shrine is trying to appeal to young people through other new programs. For example, “ecology” is one of the issues that Yasukuni Shrine has recently begun promoting. On November 11, the World Peace Commemoration Day of 2007, the shrine held a public symposium on ecology and education under the title To Live. Here is the text which advertised the symposium:

Protect the Japanese “Spirit”

Japan’s nature is unusually rich in the world

Dense forest, pure water, and mild climate have had a considerable influence on the Japanese “spirit”Japan’s education used to be outstanding and impressed the rest of the world

It provided children with the world’s highest level of academic abilityHowever, now, Japan’s nature is suffering

Japan’s education is distorted

Such conditions may seriously damage the Japanese “spirit”What is the Japanese “spirit”?

What should we do to protect the Japanese “spirit”?Let’s think about these issues, with our guest speakers, ecological mountaineer Noguchi Ken, and educational scholar Takahashi Shiro, who tackles education problems.

Noguchi is well known in Japan as a young and sincere mountaineer who regularly goes to Mount Everest and collects garbage that other mountaineers have left at various places in the mountains.

He is popular among youth and often appears on TV shows, but hardly expresses any nationalistic opinions. He seems to be apolitical and politically naïve. He perhaps feels that he should utilize any occasion to promote ecological issues, even an event organized by a controversial institution like Yasukuni Shrine. Takahashi, on the other hand, a professor at Myojo University in Tokyo, is one of the nationalist academics who belong to the Society for History Textbook Reform, an organization promoting a revisionist history textbooks. From the above-mentioned advertisement, it is clear that the real topic that the Yasukuni Shrine wished to highlight at the symposium was the controversial school textbook issue, the ecological issue and the star power of Noguchi Ken to attract an audience. Yet, it is ironic that Yasukuni Shrine, which glorifies war – one of the most ecologically damaging human activities – exploits popular ecological concern for the propagation of their real aim: to inculcate nationalism and patriotism among the youth in Japan.

The Yamato Museum and Supremacy of Japanese Technology

The Japanese government and the Ministry of Defense are also utilizing ostensibly non-militaristic issues such as scientific technology in order to quietly infiltrate nationalistic ideas into the minds of Japanese youth, in order to pave the way for the eventual abolishment of Article nine of Japan’s constitution. One such example is the Yamato Museum.

On April 23, 2005, just months before the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of the Asia-Pacific War, Kure City Maritime History and Science Museum was officially opened at the port of Kure, about 40 kilometers from Hiroshima city. Despite its name, this four-storey museum is filled almost entirely with exhibits related to the Japanese Imperial Navy. They include a huge model of the Battleship Yamato, replicas of artillery shells used by the Yamato and other Japanese battleships, a replica of the Kaiten (a human suicide torpedo) and zero fighter planes. A more accurate name would be the Kure Military History and Science Museum,” although the museum is known throughout Japan as the Yamato Museum. This refers to the main exhibit, which is a model, one-tenth the actual size of the battleship Yamato, the world’s largest, heaviest, and most powerful battleship ever constructed with nine 460mm canons firing 1.36 tonne shells. A pamphlet produced by the Kure City Council calls it “the Yamato Museum,” and the official title is not used at all. The museum’s official website also uses the name “Yamato Museum”.

Visitors to the museum pass through the entrance on the ground floor to a huge hall displaying a 26.3meter long model of the Yamato, which is the centerpiece of the museum and can be viewed from all four stories of the building.

Visitors then proceed to a separate exhibition room containing small models of many other battleships constructed at the Kure Naval Dockyard before and during the Asia-Pacific War. A series of panels explains how Kure developed into a modern industrial city and prospered, thanks to the Naval dockyard. In the center of the room is a large panel with a copy of one of the original blueprints and other panels that proudly explain the sophisticated technology used at the time to construct and assemble the world’s largest battleship. In addition, panels tracking the path the Yamato took on its last mission against more than 1,000 US ships off Okinawa. Diagrams and photos show how the ship was attacked and destroyed by U.S. planes and bombers on April 7, 1945, well before reaching the sea of Okinawa. Interviews with surviving crew members are also shown on a screen.

Yet, there is no mention of the fact that Admiral Ito Seiichi, the commander of Operation Ten-Go for which the Yamato and several other ships were mobilized, considered the mission strategically absurd strongly protested to Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Toyoda Soemu, up to the last moment. One panel circuitously notes that ‘3,056 out of 3,332 crew members met their fate alongside the ship,’ avoiding the word “dead.” (emphasis added)

The highlight of this section, however, is a large screen, which repeatedly shows a colorful 15 minute long film which explains in a very simplistic manner how post-war Japanese industrial technology, ranging from oil tankers, to automobiles, bullet trains, electric appliances, binoculars and more, developed as a result of the technology used to construct the Yamato.

Beyond these pre-war and war time exhibits, visitors proceed to another room displaying post-war industrial technology used by local factories in Kure. These appear almost as if they are advertisements for private companies. As one enters the section, a small panel mentions with scant explanation “the law for transforming former naval ports,” Most visitors pass this without really understanding the meaning of this law, which was enacted in 1950, and which applied to the four former naval base cites – Yokosuka, Kure, Maizuru, and Sasebo. The law transferred the Imperial Navy facilities of these cities to privately-owned facilities or those managed by local communities, so as to redirect their industries to peaceful ones. Article 1 of this law stated that ‘by changing former naval port cities to peaceful industrial port cities, this law aims to contribute to accomplishing the ideal of establishing a peaceful Japan.’ Ironically, however, not long after the enactment of the law, all four cities began to provide facilities for the U.S. Naval Forces in the Korean War. They soon became important bases for Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Forces. In other words, the U.S Navy and the Japanese Self Defense Forces have violated this law almost since its inception and continue to do so today.

The museum’s official website homepage states that ‘The battleship Yamato was the world’s largest battleship, secretly constructed and completed in December 1941 at Kure Naval Dockyard, as a culmination of the foremost technology of the time. On April 7, 1945, it was sunk by American planes, while en route to a mission in Okinawa, and 3,056 out of 3,332 crew members met their fate alongside the ship.

The Yamato moments after the explosion that sank it

Yet, the technology used in the construction of the battleship Yamato survived and was subsequently applied, not only to the construction of large scale oil tankers, but also to many other fields, including the production of automobiles and electric appliances, thereby supporting Japan’s post-war rehabilitation. This model of the battleship Yamato, conveys the importance of peace and brilliance of scientific technology to future generations.’ (emphasis added) Despite this grand claim, however, it is difficult to find any message about the importance of peace among the museum exhibits celebrating Japan’s wartime navy.

In May 2006, a group of concerned citizens from Kure city lodged a request to the museum to reconsider the way the museum displays and explains its exhibits, emphasizing the following four points.

(1) There is no explanation that arms and weapons including battleships are designed to kill large numbers of people.

(2) There is no reference to the fact that, in the 15 years of the Asia-Pacific War, during which most items at the museum were produced and used, Japan plundered natural resources and food in many parts of Asia and killed a large number of Asian civilians, and that at the same time some 3 million Japanese people also died. The museum chooses, simply, to emphasize proudly the different aspects of military technology.

(3) In the section on historical background, there is no reference to the forced labor of Korean and Chinese workers, nor to the underground trenches in and around Kure city made by exploiting these workers. Instead, the museum emphasizes only that the people of Kure enjoyed a modern life style from early in its history, thanks to the Navy, as they were the first in Hiroshima prefecture to have train and city water services.

(4) The museum exhibits show little consideration for visitors from neighboring Asian countries such as Korea, China and Indonesia.

In responding to this request, the director of the museum, Mr. Todaka Kazunari, stated that the museum demonstrates to visitors that there are two aspects to technology – a good one and a bad one. Ideally, he explained, visitors to the museum should understand that the abuse of technology can result in tragedy. Yet nowhere in the museum exhibits is there a reference to the “two aspects” or the “abuse of technology.”

The building of this museum was a costly exercise. Kure city spent 6.5 billion yen (approximately US$60 million), of which 1.1 billion yen was funded by the Self Defense Agency and 1.3 billion yen by the Japanese government. Given this financial support, it would seem likely that the museum’s basic policies have been influenced considerably by the official Japanese government view of the Asia Pacific War and the conduct of the Japanese Imperial Navy during the war. Yet, it is important to note that the museum does not openly express strong patriotism or militarism. Instead, as described above, it takes an indirect approach, emphasizing Japan’s wartime technological superiority in the production of battleships and urges visitors –particularly children on school excursions – to admire Japan’s military power. In this sense, there is a certain similarity between the exhibition of the model battleship Yamato and that of the B-29 bomber, Enola Gay, in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the U.S. National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. The Enola Gay is presented as evidence of U.S. military might and technological supremacy, with no information about the devastating destruction of Hiroshima City and the mass killing of civilians by the atomic bombing.

The Enola Gay at the National Air and Space Museum

The Yamato Museum actively encourages school excursions and school study tours from all over the country to the museum, falsely claiming that the museum is “the establishment from which peace messages are dispatched.” It also runs various special events and workshops for children at the museum on weekends and during school holidays. In order to attract children and young adults, the museum also has a small manga library, which is filled mostly with the manga series Uchu Senkan Yamato (The Space Battleship Yamato), one of the most popular manga which was made into a series of films, as well as a long-running TV animation series from the mid 1970s to early 80s. In fact, the story of this manga has little reference to the real battleship Yamato. Set in the year 2199, the Earth is attacked with radioactive bombs by an alien known as the Gamilas, and as a result, becomes uninhabitable. The surviving people live in refuges deep underground, and convert the ruin of the Japanese battleship Yamato into a spaceship. The space battleship departs for a long journey to the planet Iscandar, 148,000 light years away from Earth, to obtain a device called the Cosmo-Cleaner D, which can clean radiation covering the Earth. In this journey, the Yamato faces various crises that have to be overcome to save the Earth. The Yamato Museum made Matsumoto Reiji, the comic artist who produced this manga series, an honorary director of the museum. It is rather ironic that a museum located so close to the city that was the first target of the atomic bomb has little concern with the reality of the actual effects of radiation upon human beings. On the contrary, it promotes the manga which creates the myth that human beings can still survive even when all of Earth is contaminated with radiation. Fantasizing the battleship Yamato through the science fiction form of manga and animation also distracts children and youth from the real issues surrounding the battleship: the horrors of war and the sacrifice of many lives for meaningless missions.

In the first 197 days after the official opening of the Yamato Museum on April 23, 2005, one million people visited the museum. In the next 188 days, a further one million visitors viewed its exhibits, and by May 20, 2007, three million people had visited the museum. The opening of the museum coincided with the release of the film, Otokotachi no Yamato (Men’s Battleship Yamato), which became a big hit in Japan. This film does not openly glorify the suicidal mission of the Yamato, but instead romanticizes the deaths of more than 3,000 crew members of the Yamato by emphasizing the young boys’ feeling that they were sacrificing their lives in order to defend their families and lovers. Thus the film does not question the fundamental issue of sacrificing people’s lives for war. There is no doubt that the film also contributed to the popularization of the museum itself.

The museum shop sells not only toy models of the Yamato and other Japanese battleships, fighter planes, submarines and tanks, but also the serial pictorial publication, Welfare Magazine, whose cover title shows the ‘f’ of ‘Welfare’ as a pistol pointing down. The title remains a conundrum to this critic, as this glossy magazine is filled with photographs illustrating the ways and activities of the Self Defense Forces, from haircut styles, to uniforms, equipment, weapons and arms. It would appear to be a fascinating source of information to young boys whose imagination is stirred by the myths of the heroism of war.

The long-term impact of the exhibits in the Yamato Museum and Yasukuni Shrine’s various tactics for shaping the ideas of Japanese youth on war and peace cannot be underestimated. Many people throughout Japan are currently actively involved in grass-root movements opposing revision of the Japanese peace constitution, the militarization of Japan, revisions of school history textbooks, relocations and expansion of the U.S military bases on Japanese soil and the like. Some young activists are trying to use musical and visual tools to promote their campaigns. Yet in general, Japan’s grass-root movements remain narrowly focused on “political issues,” and are not developing as wide-ranging “cultural movements.” Can these movements cultivate and develop a distinctive peace-oriented popular culture – music, manga, films, theatre, fine art and the like – to reach the wider population, including children and youths. Such a popular culture must counteract the “nationalistic sentimentality” that Yasukuni Shrine inculcates, and the mythos of “technological superiority” that the Japanese government and the Ministry of Defense propagate. Such a culture would help people understand the harsh reality of war (i.e., the reality that people do not die for war, but rather, that war brutalizes and kills people), and at the same time show the values of peace, love and friendship. There is profound truth in the proverb “Si vis pacem para pace (If you seek peace, prepare for peace),” peace activists’ variation of “Si vis pacem para bellum (If you seek peace, prepare for war).”

The Are Raise video of Kyoji with English subtitles, but without the powerful war graphics, is available here.

Yuki Tanaka is Research Professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute, and author of Japan’s Comfort Women. Sexual slavery and prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation, and a coordinator of Japan Focus. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted May 8, 2008.