‘Forgetting, even getting history wrong, is an essential factor in the formation of a nation, which is why the progress of historical studies is often a danger to nationality.’ Ernest Renan

In 2002, the Japanese government built the “Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims” within the Hiroshima Peace Park. It is located less than two hundred meters from the A-Bomb Peace Museum operated by the Hiroshima City Council. This new Memorial Hall, funded and run by the Japanese government, includes the following message on one of the wall panels:

‘At one point in the 20th century, Japan walked the path of war. Then, on December 8, 1941, Japan initiated hostilities against the U.S., Great Britain and others, plunging into what came to be known as the Pacific War. This war was largely fought elsewhere in the Asia Pacific region, but when the tide turned against Japan, American warplanes began bombing the homeland, and Okinawa became a bloody battlefield. Within this context of war, on August 6, 1945, the world’s first atomic weapon, a bomb of unprecedented destructive power, was dropped on the city of Hiroshima.’

Other panels present the following statements:

‘The Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims is an effort by the Japanese national government to remember and mourn the sacred sacrifice of the atomic bomb victims.’

‘We hereby mourn those who perished in the atomic bombing. At the same time, we recall with great sorrow the many lives sacrificed to mistaken national policy.’ (emphases added)

1. Hiroshima following the atomic bombing

These formal statements clearly reflect the Japanese government’s assessment, but they also articulate widely held popular attitudes concerning Japan’s war responsibility. In other words, in the absence of explanation of any kind, the viewer is left to conclude that Japan simply, inexplicably, “walked the path of war” and the “real” war started with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941. That “real” war, in other words, did not begin on September 18, 1931, the day that the Japanese Army detonated an explosion on the South Manchurian railway, providing the pretext for the seizure of Manchuria and the establishment of Manchukuo under Japanese aegis. Nor did it begin on July 7, 1937, when the Marco Polo Bridge Incident plunged Japan into full-scale war leading to the occupation of large areas of China. In the Memorial Hall’s rendering, Japan’s major enemies in the Asia-Pacific War were the U.S. and Great Britain, not China, still less the other Asian peoples that Japan conquered following the attack on Pearl Harbor. In short, Japan was defeated by Anglo-Saxons not by Asians. Such an interpretation of the history of the 15 year war (1931-45) naturally hinders full recognition of responsibility for Japan’s abhorrent military acts and the war losses that its Asian neighbors suffered as a result of war and colonialism. It also fundamentally distorts the dynamics of power played out on the fields of colonialism and war in the first half of the twentieth century.

On the other hand, the atomic bomb is said to have been “dropped on the city of Hiroshima” as if it were a natural calamity, without identified human agency, the consequence being that many people were “sacrificed to mistaken national policy.” Thus the responsibility of American forces for the killing of large numbers of civilians is not seriously questioned. Instead, the victims of atomic bombing are simply presented as the “sacred sacrifice” of war, just as the nature of Japan’s “mistaken national policies” is left unexamined. In particular, the words “sacred sacrifice” remove any reference to who killed so many people or why and for what these people had to be “sacrificed.” This is partly due to the fact that the word “sacred” possesses a kind of religious function that blurs the historical process whereby these people became victims of war. The word “sacred” tends to refute any mundane queries regarding the background of a “sacred person.” In other words, it is widely accepted that once a person is apotheosized and becomes “sacred,” no one should catechize about his or her past. Here we can find a similarity with the “sacred souls” of soldiers enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine, where the issue of Japanese war crimes remains unquestioned.

Because non-explanations of this kind are the characteristic not only of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall but of most school textbooks and the school curriculum generally, the result is that the majority of Japanese people remain ignorant not only of Japan’s war responsibility, but also of the history of the Asia-Pacific War in general.

It is often said that the Japanese people tend to see themselves as victims of war rather than as assailants, largely due to the experience of U.S. aerial bombing towards the end of the war, culminating in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Undoubtedly this was one of many factors that contributed to such a popular perception.

Indeed, the A-Bomb Peace Museum operated by the Hiroshima City Council is filled predominantly with exhibits highlighting the victimization of the citizens of Hiroshima as a result of indiscriminate bombing using the atomic bomb. Although there is a brief explanation of the Nanjing Massacre in relation to the activities of the Imperial Army dispatched from Hiroshima to China prior to the atomic bombing, the museum invariably presents the atomic bombing of the city as the historically unprecedented and unparalleled victimization of Japanese citizens. Indubitably the museum conveys a powerful anti-nuclear message. Yet it is interesting to note that the museum exhibits scarcely nothing except information on the bombing of Hiroshima, and even the bombing of Nagasaki and other landmarks of nuclear history are hardly mentioned. Hence the museum fails to bring to light fundamental features common to all victims of atomic bombings, nuclear tests, indiscriminate bombing, and war in general.

2. Collecting and classifying rubble that would

eventually be exhibited at the Peace Memorial

Museum.

Yet even this perception of “war victims” is rapidly fading, and younger generations no longer recognize their nation’s war responsibility or even the price that war exacted on their own society. Indeed, few have sufficient knowledge of Japan’s modern and contemporary history to hold opinions concerning Japan and war.

We cannot give a simple answer to the question of why many Japanese failed to nurture a strong sense of war responsibility. In this essay, I examine some important factors that have hindered the cultivation of a clear public sense of Japanese war responsibility. I will particularly concentrate on the 15 years after the war (1945 – 1960), the period in which the fundamental framework of the Japanese popular concept of “war responsibility” was molded. This is because of my strong belief that a lack of of war responsibility among younger generations is not simply due to a lack of education, but is deeply rooted in the very fabric of Japanese popular thinking on war issues formulated and implanted in the early post-war period.

One of the new programs that GHQ (General Headquarters of the Allied Occupation Forces) introduced in the early stages of the occupation was “the re-education of the Japanese.” The CIE (Civil Information and Education Section) of GHQ was given the task of teaching Japanese citizens “the truth” about the war by revealing Japanese war crimes and highlighting the devastating consequences of the war including Japan’s destruction and defeat. Between December 8 and 17, 1945, the CIE required all Japanese national newspapers to publish a series of articles drafted by CIE on the history of the Pacific War. At the same time, NHK (the Japan Broadcasting Commission) ran a serial radio program called “This is the Truth.” This series, designed and produced by CIE, was broadcast once a week over 10 weeks from December 9, 1945. The content of the two series of articles and broadcasts can be summarized in the following points.

1) Although they pinpoint the Manchurian Incident of 1931 as the start of the war and acknowledge the continuity between Japan’s invasion of China and the Sino-Japanese War as well as the Pacific War, Japan’s colonial rule of Taiwan and Korea is completely ignored.

2) The decisive role of U.S military forces in determining the outcome of the war in the Pacific is singularly emphasized, while the anti-Japanese resistance carried out by Chinese forces over fifteen years, and by various Southeast Asian forces over four years, are ignored. The single exception is brief mention of Filipino guerrillas who collaborated with American forces.

3) The responsibility of a handful of Japanese military leaders is emphasized, while Emperor Hirohito and his close associates within the Imperial Court as well as business and media leaders, are simply characterized as “moderate groups” in contrast to the militarists.

4) Emphasizing Japanese military leaders’ concealment of the actual circumstances of the war creates a popular image that the Japanese people were deceived by their military leaders. The result was therefore to ignore the structural foundations that led Japan on the road to colonialism and war.

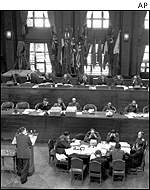

On December 8, 1945, the same day that the newspaper series commenced, General MacArthur issued an order to set up the IPS (International Prosecution Section) for the IMTFE (International Military Tribunal for the Far East, popularly known as the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal) and appointed an American lawyer, Joseph Keenan, as the chief prosecutor. A-class war crime suspects had already been arrested and the IMTFE was planned to open in May 1946. In short, one of the aims of the media exercises directed by CIE was to prepare the Japanese people to accept the legitimacy of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal on basis of the official American interpretation of the Asia-Pacific War.

3. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal

The judges of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal were chosen from U.S. allies who fought in the Pacific War. The result is that the justices were from 11 nations, namely the U.S., the U.K., the Soviet Union, France, Australia, Canada, China, Holland, New Zealand, India and the Philippines. There were three Asian judges including one from China, which sustained by far the largest casualties of Japanese invasion (serious estimates range between ten and twenty million war-related deaths), as well as India and the Philippines. However, despite that fact that millions of Asian died in the war and it was Asia that bore the brunt both of Japanese colonialism and war deaths, no legal representative was drawn from Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Burma, Indo-China, Korea or Taiwan, and the court was dominated by Western allies of the U.S. It should also be noted that the U.K., France and Holland as well as the United States were the colonial rulers of large areas of Asia, in which national independence movements were underway including the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, Singapore, Burma, the Philippines and Indochina. Therefore, it is not surprising that Japanese responsibility toward Asian people was framed by the tribunal in ways that focused on war atrocities and elided issues of colonialism.

In addition, General MacArthur and the U.S. government protected Emperor Hirohito from indictment as a war criminal, kept him on the throne, and shielded him even the necessity to testify. Their goal was, of course, to exploit the emperor system in order to smooth occupation control of Japan. For this purpose, GHQ presented Hirohito as having been manipulated by the military leaders, denying all direct exercise of power over the Imperial Forces – in other words, the emperor, too, was a victim of the war. Further, Hirohito was credited with taking the crucial initiative to end the war, that is, he emerged during the occupation as the peacemaker who saved Japan from annihilation. MacArthur skillfully burnished the image of Hirohito of the peacemaker as well as the key figure who “voluntarily” led the Japanese government to formulate the new democratic Constitution renouncing all Japanese military forces. The U.S. in short, with the enthusiastic support of the Japanese government thus propagated an image of a “democratic monarch” and a “peace monarch.”

In short, CIE’s “re-education programs” together with the American framing of the War Crimes Tribunal and the projection of the myth of the peace emperor, had a huge impact upon the formation of the postwar Japanese self-image. That is, the Japanese were pitiable war-victims like their humane emperor, who were deceived by military leaders represented by General Tojo Hideki. The result was to relieve the Japanese people of the necessity to reflect seriously upon the colonization and oppressive rule of Taiwan and Korea by Japan, war crimes such as the Nanjing Massacre that their troops committed against the people of various nations in Asia, and the emperor’s ultimate responsibility for the sufferings of vast numbers of Asian people. This lack of reflection concerning responsibility towards their Asian neighbors is central to understanding why many Japanese still cannot overcome their prejudice toward other Asians. John Dower makes the point well in his book, Embracing Defeat, as follows: ‘One of the most pernicious aspects of the occupation was that the Asian peoples who had suffered most from imperial Japan’s depredation – the Chinese, Koreans, Indonesians and Filipinos – had no serious role, no influential presence at all in the defeated land. They became invisible. Asian contributions to defeating the emperor’s soldiers and sailors were displaced by an all-consuming focus on the American victory in the Pacific War.’ (p.27)

It should also be noted that one third of young Japanese men, who were born between 1920 and 1922, and who comprised the largest segment of the Japanese Imperial Forces, died by the end of the war. Consequently many surviving men came to hold a deep sense of guilt about not having died. This quite probably contributed to preventing them from engendering an acute sense of responsibility for the Asian victims of the war. Typical of their attitude, was the determination to adopt a strong resolve to work hard to help rebuild Japan on behalf of their deceased friends, i.e., “true war victims” in their eyes.

This popular self-perception, which highlighted Japanese “victim-hood” and downplayed their war responsibility to Asia, was further augmented with signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in September 1951. This treaty marked the formal cessation of the Asia-Pacific War, ended the occupation of Japan by the Allied (primarily American) forces, and simultaneously restored Japan’s independence, and consummated a US-Japan security treaty that provided for the permanent stationing of U.S. forces that continues to this day, and lashed Japan firmly within the arc of U.S. military power. With the refusal of the Soviet Union, Poland and Czechoslovakia to sign the treaty, and with neither the People’s Republic of China (Beijing government) nor the Republic of China (Taiwan) invited to attend, despite the fact that China had suffered the heaviest casualties in the war against Japan, the treaty was clearly revealed as a Cold War instrument of the U.S. In addition neither North Korea, fighting the U.S. in the Korean War, nor South Korea were invited to attend, on the dubious ground that Korea was not a state at the time of Japan’s surrender in 1945. India and Burma refused to participate in the conference, regarding it as a “rigged affair” so that only four Asian nations – the Philippines, Indonesia, Ceylon and Pakistan – attended the conference. Yet Indonesia never ratified the treaty, but signed a separate peace treaty with Japan in 1958. The Philippines only ratified the treaty after it came into effect. In this way, the “invisibility of Asia” was again conspicuous at the San Francisco Peace Treaty Conference.

4. Prime Minister Yoshida

Shigeru signing the San

Francisco Peace Treaty

The question of reparation is similarly important for locating Japan in comparative perspective, particularly vis-à-vis German behavior. Under U.S. pressure the Allied nations waived all reparation claims in accordance with Article 14 of the treaty. Later, Taiwan, China (both Beijing and Taipei), the Soviet Union and India likewise renounced the right to reparations. Thus, Japan eventually paid modest war reparations only to Burma, the Philippines, Indonesia, and South Vietnam. In addition, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and South Korea eventually received small amounts of economic aid and cooperation as Japan rejected the idea of paying reparations.

We have shown that the San Francisco Peace Treaty was less a peace treaty than an agreement to lash Japan to U.S. aims in the Asia Pacific. The combination of the Treaty and the AMPO Security Pact signed on the same day strongly reflected America’s anti-communist policy and intention to use Japan to contain the Pacific side of the communist bloc (namely the Soviet Union, China and North Korea) by retaining U.S. military bases in Japan, in particular, in Okinawa. Therefore the treaty as a whole was lenient with respect to Japan’s war responsibility. The Japanese government did perfunctorily acknowledge its war responsibility described in Article 11: “Japan accepts the judgments of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and of other Allied War Crimes Courts both within and outside Japan, and will carry out the sentences imposed thereby upon Japanese nationals imprisoned in Japan.” However, the same article also opened the possibility that Japanese B- and C-class war criminals who were tried for crimes against humanity such as war atrocities, and who constituted the great majority of war criminals, would be granted clemency, reduction of sentences or parole if the foreign government that conducted the war crimes tribunal agreed. Therefore, shortly after the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect in April 1952, a movement demanding the release of B- and C-class war criminals began, emphasizing the “unfairness of the war crimes tribunals” and the “misery and hardship of the families of war criminals.” In this way, Japanese B- and C-class war criminals came to be viewed as “victims of war” by Japanese people generally. By the end of 1958, all Japanese war criminals, including A-, B- and C-class were released from prison and politically rehabilitated.

As a result, by the early 1950s the basic framework of popular thinking on war issues, which has hamstrung the development of a clear and deep sense of Japan’s national responsibility ever since, was well implanted within Japanese society. For its part, the Japanese government had adopted a kind of double-standard ¬– on the one hand it officially accepted as a foreign policy Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, including the judgment of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, while refusing to accept war responsibility as a domestic policy. This is evident both in the large-scale amnesty of those convicted by the Tokyo and the B- and C-class trials, and in the failure to embed responsibility for the consequences of the war in its public statements, in its textbooks, or in substantial reparations to the victims of colonialism and war. This contradiction, which continues today, has been the main cause of friction between Japan and other Asian nations, in particular China and South Korea. It is interesting to note that even such hawkish politicians as Nakasone Yasuhiro could not openly negate the legality of Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty while serving as prime minister. Even the current Prime Minister, Koizumi Junichiro, does not publicly contradict the Japanese government’s official interpretation of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

From around 1950, military histories written by former staff officers of the Japanese Imperial Army and Navy Forces, such as Tsuji Masanobu, Kusaka Ryunosuke and Hattori Takushiro, began to be published and many became bestsellers. However, as typified by Hattori’s Daitowa Senso Zenshi (General History of the Great East Asian War), these popular books are written strictly from the perspective of explaining Japan’s defeat, invariably attributed to the lack of natural resources and economic power. None address questions of Japanese colonialism, aggression or the atrocities that Japanese troops committed throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Indeed, Hattori does not even mention Japan’s warfare against guerilla forces in China, the Philippines or elsewhere, as he did not regard “guerrillas” as proper military forces. For him “military history” was the history of war conducted only by regular military troops, i.e., in this case the Japanese Imperial Forces versus the Allied Forces.

However, in the late 1940s and early 1950s a number of books containing moving stories conveying strong anti-war sentiment began to be published. One such influential publication was Kike Wadatsumi no Koe (Listen to the Voices from the Sea), a 1949 collection of the letters home, diaries and wills of young student soldiers (mostly kamikaze pilots). Although this book had a profound anti-war message, one that resonated deeply with the Japanese people who had experienced the destruction of their cities from the air in the final months of the war, it raised few questions of Japanese responsibility for their deaths. It powerfully presents the young students who died during the war as sympathetic “victims” of a war waged by irresponsible military leaders. Nowhere, however, does it suggest Japanese responsibility for Asian victims of the war. Two other remarkable books which appeared in the same period were semi-autobiographical novels – Furyoki (Prisoner of War) and Nobi (Fires on the Plain) – both written by Ooka Shohei, a former Japanese POW captured by the U.S forces in a jungle in the Philippines. (Fires on the Plain was made into a film in 1959.) In these novels Ooka skillfully describes the painful physical and psychological problems of a sick and emaciated Japanese soldier struggling to survive the jungle fighting. These outstanding literary works convey a profound anti-war sentiment. Yet again, in both novels, the focal point is a young Japanese victimized by war, and little attention is paid to the Filipinos who were the targets of brutal Japanese military conduct.

5. Listen to the

Voices From the Sea

Another book which became very popular in this period was Biruma no Tategoto (The Harp of Burma) by Takeyama Michio. It is a story about a young Japanese soldier in Burma, who deserted his troop and became a Buddhist monk. Even after the end of the war, he remained in Burma in order to appease the souls of his dead comrades. Here too, the plight of the Burmese people is completely ignored. Indeed, the author did not ever visit Burma. (The Harp of Burma was made into a film in 1956, and again in 1985.)

From the mid 1950s, numerous memoirs of former soldiers were published. Most were written by low ranking officers and noncommissioned officers, explaining how hard and bravely ordinary Japanese men like themselves had fought during the war and how honorably they had fulfilled their duties as Imperial soldiers. An interesting characteristic of these memoirs is that many authors criticized military leaders’ conduct of the war, including the abandonment of their soldiers in the final months of the war. In this sense there is a certain similarity with the book, Listen to the Voice from the Sea. Yet these publications, too, contributed to the existing popular perception of the Japanese as war-victims, and failed to address questions of war crimes committed by Japanese against Asians.

In the latter half of the 1950s, partly due to popular peace movements in Japan against U.S. nuclear tests conducted in the Pacific, the re-militarization of Japan and the existence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, lively discussions regarding the Japanese people’s war responsibility took place among the so-called progressive intellectuals. One product of this ferment was the publication of the book Showa-shi (A History of Showa) coauthored by three prominent Marxist historians, Toyama Shigeki, Imai Seiichi and Fujiwara Akira. The question of “war responsibility” in this case, however, centered on the failure of Japanese citizens to prevent the invasion of China. That is, the focus was on citizens’ failure to halt militarism and fascism. An important issue, to be sure. But little was said about the nature of Japanese killing and atrocities in China and nothing about the impact of Japanese militarism on other Asian nations. Another important book published in this period is Gendai Seiji no Shiso to Kozo (The Thought and Structure of Modern [Japanese] Politics) by political scientist Maruyama Masao. Maruyama provided a theoretical explanation of the development of Japanese fascism and militarism in conjunction with the strengthening of emperor ideology from the Meiji era, but nowhere did he address the question of the Japanese people’s war responsibility. In short, all of these works were heavily inward-looking rather than outward-looking. Furthermore, these debates were conducted within a limited academic circle and in left-wing circles associated with the communist and socialist parties. The result was that they had limited impact on popular perceptions of the war.

Popular feature films produced in the 1950s also shaped popular images of the Japanese as war victims, including feature films directly dealing with B- and C-class war criminals. Among them the most widely viewed was the 1958 film Watashi wa Kai ni Naritai (I Want be a Shellfish). This is a story of an innocent man, who happily returned home to his wife after the war to resume a normal life as a local barber only to be arrested as a war criminal and igiven the death sentence. His crime was to have carried out the execution of an American POW, a surviving crew-member of a B-29 bomber that was shot down over Japan. The film depicts him as an extremely unfortunate man in the lowest rank of the Japanese Imperial Army, who could not refuse an order handed down from senior officers. The result is that he emerges not only as a typical victim of Japanese militarism but also of the capriciousness of the war crimes tribunal. (This film was remade for television in 1994.) Another film, Kabe Atsuki Heya (Room With a Thick Wall), produced in 1953 is about B- and C-class war criminals detained in Sugamo Prison and it too presents the prisoners as victims of war, while highlighting some legal defects of the tribunal.

Two other types of war-related feature films were produced in the 1950s: films on the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and those presenting the brutality experienced by Japanese rank and file soldiers in the Imperial Army. Between 1950 and 1955, several films about Hiroshima and Nagasaki were produced. Amongst them were Nagasaki no Kane (The Bell of Nagasaki, 1950), Nagasaki no Uta Wasureji (Never Forget the Song of Nagasaki, 1952), Genbaku no Ko (Child of the A-Bomb, 1952), Hiroshima, 1953, and Kurosawa Akira’s Ikimono no Kiroku (Record of A Living Being, 1955). The last three films are particularly impressive from storytelling and filmic perspectives, and do not simply present Hibakusha (A-bomb victims) as the Japanese victims of war. Each has a profound and universal anti-nuclear weapon message. Yet none examines the impact of Japanese war on Asian people, and none poses serious questions of Japanese war responsibility.

The second group of films is represented by Shinku Chitai (Zone of Emptiness, 1952), based on the novel of the same title by Noma Hiroshi, and Ningen no Joken (Human Condition, 1960) based on a long story written by Gomikawa Junpei. Both films denounce the extreme brutality inflicted upon Japanese soldiers by their superiors. Although the latter film briefly touches on the atrocities Japanese troops committed against the Chinese, the main theme of these films is still the victimization of Japanese men through widespread inhumane conduct within the Japanese military forces. At the time, the most popular work in this category was a series of comedies called Nitohei Monogatari (The Story of A Private). In total ten films were produced in this immensely successful series between 1955 and 1961. It ridiculed the military system and ideology of the Japanese Imperial Forces. In each film, rank and file soldiers are severely maltreated by their seniors, and commanding officers are invariably corrupt and selfish. Each film ends, moreover, with a revolt by rank and file soldiers against their officers at the end of the war – a happy ending for audiences empathizing with the soldiers. In one film in this series, Japanese soldiers rescue Japanese comfort women captured by merciless Chinese soldiers, and a Chinese merchant closely collaborating with Chinese forces is presented in a dark light. However, not one of the films in this series depicts Japanese atrocities against local people in occupied territories.

Another popular film that deeply shaped the Japanese self-image as war-victims was Godzilla, particularly its original 1954 version. As I analyzed in an earlier article, ‘Godzilla and the Bravo Shot: Who Created and killed the Monster?’, in many aspects Godzilla symbolized B-29 bombers that repeatedly attacked cities from Hokkaido to Okinawa and dropped A-bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Many scenes in this film evoked U.S. aerial attacks that took the lives of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in the final months of the war. Thus, although the film’s effect is indirect, presented as it is through an entertaining monster film, it reaffirmed and strengthened the Japanese popular concept of being war victims not perpetrators of war crimes. Overall, these films sent a remarkably consistent message and hence their effect in shaping popular understanding of the Asia-Pacific War was vast.

Considering that feature films screened at local cinemas were one of the few sources of entertainment available to the Japanese public in the post-war period, the above-mentioned films undoubtedly played a considerable role in shaping a widely shared view of the Asia-Pacific War amongst the general population. In 1958, for example, Japanese films attracted more than 1.1 billion viewers throughout the country.

In early 1965, U.S. forces began full-scale bombing of North Vietnam. Over the next decade, large numbers of bombers, troops and military supplies were dispatched from U.S military bases in Japan, including Okinawa. In April that year, “Beheiren” (Japan Peace for Vietnam Alliance) was formed to oppose U.S. aggression and resist Japanese support for the U.S. war effort in Vietnam. Popular fears that Japan might again be dragged into war provided an important foundation for a relatively strong anti-war movement. Oda Makoto, a writer who led this movement, promoted the idea that the Japanese people should avoid becoming “war perpetrators” by refusing to collaborate with the U.S. in bombing and killing Vietnamese. He pointed out that, with respect to Japan’s own war experiences, hitherto ample attention had been paid to the aspect of their own victimization, but few had addressed the responsibility of the Japanese as assailants. To grasp the possibility of Japanese becoming assailants in the Vietnam War, he stressed the necessity to clearly recognize the historical fact that the Japanese people had been both victims and assailants in the Asia-Pacific War. It was a powerful appeal at a time when not only the general population but also the majority of intellectuals were preoccupied with only one side of their war experiences, that as victims both of the Japanese military and of U.S. bombing.

In addition to the Beheiren movement, efforts to normalize the relationship between Japan and China that started in the early 1970s stimulated debate on Japan’s war responsibility to the Chinese people. In this context, journalists such as Honda Katsuichi published detailed reports about the Chinese victims of Japanese military atrocities, notably those committed during the Nanjing Massacre. Some academics also started conducting research on war crimes that Japanese troops committed in China and other occupied territories of Asia. From the late 1970s, scholars such as Ienaga Saburo, Fujiwara Akira, Eguchi Keiichi and Oe Shinobu wrote about Japan’s war responsibility, posing serious moral questions. Encouraged by the work of these scholars, detailed accounts of hitherto unknown cases of Japanese war crimes – e.g., bacteriological warfare, massacre of POWs and exploitation of “comfort women” – were produced in the 1980s and 90s by historians such as Tsuneishi Keiichi, Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Kasahara Tokuji, Utsumi Aiko and others. The impact of such scholarly work upon intellectual circles was profound.

Yet the effects that progressive political movements such as Beheiren and academic research on Japanese war crimes had upon popular attitudes in Japan was insufficient to overcome the one-sided victimization perspective on the Asia-Pacific War. The dominant Japanese self-image as war victims infiltrated deeply into the psyche of many Japanese throughout the nation in the 1950s and 60s through both official and popular culture channels. It was no easy task for a progressive political or academic movement to overcome that established view.

From the early 1990s, a backlash against the above-mentioned progressive academic work was touched off by nationalist scholars, who denied the historical record of Japanese wartime atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre and the comfort women, and called on Japanese to take pride in their war record. Cartoonist Kobayashi Yoshinori was particularly influential in transmitting their views to a vast popular audience, and achieving a certain success in undermining the credibility of critical scholars. This backlash reverberated through the Japanese Ministry of Education’s approval of the school textbook produced by nationalist scholars associated with the Tsukurukai (The Association for Producing New Textbooks) group and government introduction of a nation-wide school program to inculcate patriotism. In addition, as a result of Prime Minister Koizumi’s stern rejection of the criticism of neighboring nations regarding his visits to Yasukuni Shrine, where Class A-war criminals are enshrined, and Foreign Minister Aso Taro’s publicly urging the Emperor to visit Yasukuni Shrine, the issue of war responsibility is again a national and international issue. The Liberal Democratic Party’s plan to amend the Japanese Peace Constitution in order to convert Japan’s Self Defense Forces to a fully legitimate military force should be viewed in light of the question of war responsibility.

To grasp the rise of neo-nationalism in Japan in the 1990s, it is necessary to understand its close interrelationship with contemporary socio-economic phenomena such as “the bursting of the bubble economy,” “financial crisis,” “globalization,” and “growing inequality.” But we should also contemplate the entire framework of ethics, including the sense of moral responsibility. Only when the Japanese people fully accept moral responsibility for the hardships inflicted on Asian people through colonialism and war, will it be possible to achieve the aim described in the preface of their Constitution “to occupy an honored place in an international society striving for the preservation of peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth.”

References

* John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (W.W. Norton & Company/The New York Press, New York, 1999)

*Awaya Kentaro, ‘The Tokyo Tribunal, War Responsibility and the Japanese People’ translated by Timothy Amos.

* Oda Makoto, Nanshi no Shiso (Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo, 1991)

* Takahashi Tetsuya, Sengo Sekinin-Ron (Kodansha, Tokyo, 2005)

* Takahashi Tetsuya, Kokka to Gisei (Nippon Hosho Kyokai, Tokyo, 2005)

* Yoshida Yutaka, Nipponjin no Senso-kan (Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo, 1995)

Yuki Tanaka is Research Professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute, author of Japan’s Comfort Women. Sexual slavery and prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation, and a coordinator of Japan Focus. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted August 20, 2006.