Class and Work in Cultural Capitalism: Japanese Trends1

Yoshio SUGIMOTO

Paradigm Shift: From Homogenous to Class-divided Society

A dramatic paradigm shift appears to be underway in contemporary Japanese society, with public discourse suddenly focusing upon internal divisions and variations in the population. At the beginning of the 21st century, the nation has observed a drastic shift in its characterization from a uniquely homogeneous and uniform society to one of domestic diversity, class differentiation and other multidimensional forms. The view that Japan is a monocultural society with little internal cultural divergence and stratification, which was once taken for granted, is now losing monopoly over the way Japanese society is portrayed.2 The emerging discourse argues that Japan is a kakusa shakai, literally a ‘disparity society’, a socially divided society with sharp class differences and glaring inequality. The view appears to have gained ground during Japan’s prolonged recession in the 1990s, the so-called lost decade, and in the 2000s when the country experienced a further downturn as a consequence of the global financial crisis.

The new image of Japan as a class-divided and unequal society has resulted not so much from intellectual criticisms levelled at the once dominant model as from public perceptions of changing patterns of the labor market. In mass media, on one end of the spectrum, the new rich who have almost instantly amassed vast wealth in such areas as information technology, new media and financial manipulation are celebrated and lionized as fresh billionaires.

At the other end of the spectrum are the unemployed, the homeless, day laborers and other marginalized members of society who are said to form karyū shakai (the underclass), revealing a discrepancy which gives considerable plausibility to the imagery of class-divided society.

At the heart of the controversy is job stability which used to be the hallmark of Japan’s labor market. One out of three employees are now ‘non-regular workers’ whose employment status is precarious. Even ‘regular’ employees who were guaranteed job security throughout their occupational careers have been thrown out of employment because of their companies’ poor business outcomes and the unsatisfactory performance of their own work. Moreover, in regional economic comparisons, affluent metropolitan lifestyles often appear in sharp contrast with the deteriorated and declining conditions of rural areas.

Reflecting these developments, scholarly class analysis has attained center stage in public discussion. In sociology, debate continues to rage over the extent to which social mobility to the privileged upper middle white-collar sector Japan has declined.3 In labor economics, many researchers focus their attention on how Japan’s level of social inequality – measured by the Gini index – compares with those of other developed societies.4 In family sociology, empirical studies show that intra-class marriages within identical occupational and educational categories remain predominant, and ‘ascriptive homogamy’ is most robust among university graduates, with inter-generational class continuity enduring most firmly in most educated strata of Japanese society.5 In the field of education, about three quarters of the students of the University of Tokyo, the most prestigious university in Japan, are the sons and daughters of company managers, bureaucrats, academics, teachers and professionals.6 In poverty studies, one in seven workers is estimated to live under the poverty line in Japan,7 a condition that hardly makes the country a ‘homogeneous middle-class society.’

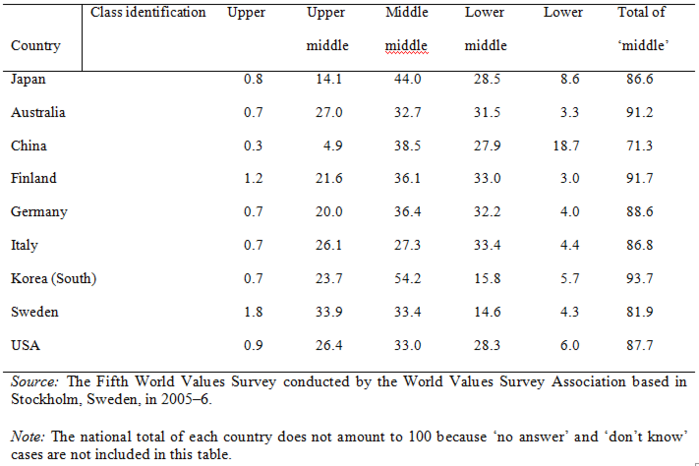

Table 1: International comparison of ‘middle class consciousness’ (%)

Still, a sobering reality prevails. Despite the claim of the emergence of kakusa shakai, an overwhelming majority of Japanese continue to regard themselves as belonging to the ‘middle class,’ a pattern that has persisted for decades.8 Yet, as Table 1 shows, comparative studies of class affiliation in a number of nations found that 80–90 percent of people identify themselves as ‘middle class,’ which suggests that this phenomenon is far from being unique to Japan.

Debate and Caution about the Kakusa Society Thesis

While gaining broad acceptance, the so-called kakusa society thesis has been subject to animated debate and must be examined with caution.

First of all, the assertion that Japanese society has suddenly become a kakusa society raises much skepticism. There is much well founded argument that Japan has always been a class-divided and stratified society and was never a uniquely ‘middle-class society’ as described by the Nihonjinron model. From this perspective, an abrupt shift took place in public awareness and sensitivity, not in empirical substance and reality. Even at the prime of the ‘uniquely egalitarian society’ argument, numerous studies demonstrated that such claim may represent only the tatemae side of Japanese society. Some comparative quantitative studies suggest that Japanese patterns of socioeconomic inequality show no systematic deviance from those of other countries of advanced capitalism. The overall social mobility rate in Japan is basically similar to patterns observed in other industrialized societies.9

The second proviso bears upon the optical illusion that appears to have persisted during the high economic growth era. There is no doubt that the high-growth economy of postwar Japan led to changes in the occupational composition of the population and shifted large numbers from agriculture to manufacturing, from blue-collar to white-collar, from manual to non-manual, and from low-level to high-level education.10 However, this transfiguration left a false impression – as though industrialization were conducive to a high measure of upward social mobility. In reality, the relative positions of various strata in the hierarchy remained unaltered. For example, the educational system which produced an increasing number of university graduates cheapened the relative value of degrees and qualifications. To put it differently, when everyone stands still on an ascending escalator, their relative positions remain unaltered even though they all go up. A sense of upward relative mobility in this case is simply an illusion. When the escalator stops or slows down, it becomes difficult for the illusion to be sustained. The occupational system cannot continue to provide ostensibly high-status positions, and eventually it must be revealed that some of the social mobility of the past was in fact due to the inflationary supply of positions. This is exactly what many in the labor force began to feel when Japan’s economy came to a standstill, recording negative growth in the 1990s and entering into a deflationary spiral in the early 2000s. The reality of class competition began to bite only when the economic slowdown failed to discernibly enlarge the total available pie.

Third, a widening gap between haves and have-nots may be exaggerated because of the increase in the proportion of the aged in the population. Since social disparities are the largest among senior citizens, an aging society tends to show a greater chasm between the rich and the poor. The demographic transformation towards a greying society overstates the general levels of class differentiation of the total population.

Fourth, Japan’s socio-economic disparities were accelerated not only by unorganized structural transformations but by deliberately engineered policy changes in the taxation system. They have decreased the rate of progressive taxation with the result that its redistribution functions have been weakened. For one thing, the consumption taxation scheme was put into motion in 1989, making it necessary for each consumer to pay five percent of the price of purchased goods as sales tax. This system benefits the wealthy and harms the poor, because the consumption tax is imposed on all consumers in the same way regardless of their incomes and assets. Further, the reduction of the inheritance tax rate in 2003 has lessened the burdens of asset owners in the intergenerational transfer of ownership. This advantaged the relatively rich and enhanced class discrepancies in this area.

Finally, one would have to see the perception shift in class structure in Japan from the perspective of the sociology of knowledge. Apparent or real, recent changes in class situations took place close to the everyday life of opinion makers and data analysts. Even when economic hardship and class competition were daily realities in the lower echelons of Japanese society, many of these commentators paid little heed to the issue because they occupied privileged positions distant from the lower levels of social stratification. However, their perceptions began to alter with the shifting class structure affecting their acquaintances and friends in their networks as a consequence of the economic stagnation and downturn in the 1990s and 2000s. The job security of full-time employees in the elite track of large companies is now at risk.11 The upper white-collar employees, a category that comprises managers and professionals, are an increasingly closed group which the children of other social strata find it difficult to break into.12 A decline in scholastic achievements even among the pupils of the upper middle classes and above has aroused concern among parents.13 There are grounds to suspect that the class position of ‘class observers’ influences their sensitivity to stratificational divisions in Japanese society.

Job Market Rationalization

The world of employment constitutes the center of debate about class and inequality in contemporary Japan. While the familial and paternalistic ‘Japanese-style’ model remains entrenched in Japan’s work culture, the prolonged recession of the 1990s and the subsequent penetration of globalizing forces into the Japanese economy has seen two fundamental shifts in the system of work – the casualization of the workforce and the introduction of performance-based employment.

Casualization of Labor

The first distinctive trend is the casualization of the labor force, a development that has been deemed a major factor that has contributed to the widening inequality between social classes. The restructuring that many companies launched in the face of the sluggish economy produced a growing number of part-time and casual workers and sharpened the line of demarcation between regular employees (seishain) and non-regular employees (hi-seishain). Regular employees encompass the full-time salaried workers who enjoy various company benefits, with many relishing the privilege of ‘lifetime employment.’ Non-regular employees include a variety of impermanent workers with disposable employment status and unstable wage structure. With economic rationalism forcing managers to minimize the costs of employment, approximately seventeen million workers, one out of three employees, now fall into the category of non-regular employees.14 It is estimated that more than half of working women and two out of five young employees belong to this group. Many of these non-regular workers form the ‘working poor,’15 a class of individuals who attempt to work hard in vulnerable jobs but are unable to get out of the cycle of underemployment and undersubsistence. Because of their vulnerable positions, many of them submit tamely to this condition and fail to demonstrate their dissatisfaction openly for fear of their employers refusing to renew their existing contract.

These marginalized employees comprise a few subcategories, some of which overlap with each other. The first of these are made up of the so-called part-time workers. Though classified as part-timers, many in this group work for thirty hours a week and differ little from full-time regular employees in terms of working hours and the substance of the jobs they perform. Married women who work to help support family finances far outnumber other types of part-timers. Generally, these ‘full-time part-timers’ receive low hourly wages, stay in the same position for years without career prospects and rarely have the privilege of joining the employee welfare pension system to which employers make contributions.

The second subcategory consists of those who engage in arubaito, a Japanese term derived from the German, which includes a variety of side jobs. Many students do after-school or vacation jobs to cover the costs of their school life. Moonlighters who earn extra money from casual jobs also belong to this category. While part-timers normally designates simply those who work less than full-time, most of those who perform arubaito are regarded as having full-time work (including schoolwork).

In popular parlance, the term friiter (freeter) is an established classification that combines these two subcategories (though excludes married female part-timers) and signifies those young workers who are ostensibly willing to engage in casual work on their own volition. The term comes from the English word free combined with part of the German term Arbeiter (people who work) and invokes the image of free-floating and unencumbered youths who work on and off based on their independent will, though the reality behind this image is highly complex.16 Many are the so-called ‘moratorium type’ youths who are buying time against the day when they could obtain better employment status, after dropping out of either school or other work without clear plans for their future. Some set their sights on being hired as regular employees despite the diminishment of these posts over time. Others accept casual work in the hope of obtaining ‘cultural’ jobs in the arts or doing skilled craftwork, though paths to long-term employment in such areas are narrow and limited. Still others simply drift in the casual job market, living week by week or month by month, with no aspirations for their future life course.

There are also other forms of non-regular workers, including contract employees (keiyaku shain) who are employed in the same way as regular workers only for a specified contract period; temporary workers (haken shain) who are dispatched from private personnel placement agencies; and part-time employees who work for a few years after retirement under a new contract (shokutaku shain).

These non-regular workers are now firmly embedded into the Japanese economy which cannot now function without their services. They are quite noticeable in Japan’s highly efficient and fast-paced urban life, at the counters of convenience shops and petrol stations and in fast-food restaurants, some of which are open twenty-four hours a day. One can also observe many non-regular workers among middle-aged female shop assistants in supermarkets, elderly security guards at banks and young parcel-delivery workers from distribution companies.

The casualization of employment poses a particularly serious issue to workers in the prime of their working lives. Those between twenty five and thirty five years of age, who entered the job market during Japan’s ‘lost decade’ in the 1990s, form the nation’s ‘lost generation’17 and constitute the bulk of non-regular workers. Without having much hope for the future, some drift into the life pattern of the so-called NEET, youth who are never educated, employed or vocationally trained. It is telling that, among males in their early thirties (30–34 of age), only 30 percent of non-regular workers are married, half the rate of regular workers (59 percent).18

Performance-based Model

The second emerging trend that departs from the conventional internal labor market model is the rise of new work arrangements, in which short-term employer evaluations of an employees’ market value and job performance form the key criteria determining remuneration and the continuation of employment. Some enterprises have started to offer large salaries to employees with special professional skills and achievements while not ensuring job security.

These companies no longer take years of service as a yardstick for promotion and wage rise and have thus opened ways for high achievers to be rewarded with high positions and exceptional salaries regardless of age or experience. Under this scheme, many employees opt for the annual salary system and receive yearly sums and large bonuses subject to their achievement of pre-set goals. Their job security would be at risk if they failed to meet the set targets. It has been argued that this system provides good incentives to ambitious individuals and motivates them to accomplish work in a focused and productive manner. Though not representative of a majority, a few bright success stories of high flyers who have chosen this path are splashed in the mass media from time to time. Head-hunting and mid-career recruitment became rampant among high flying business professionals in the elite sector.

While an increasing number of large corporations adopt the performance-first principle in one way or another, the number of employees who elect the annual salary system remains a minority. On the whole, this form of employment is more widespread in the service sector than in the manufacturing industry.

The performance model has been subject to criticism in many respects. The system, in reality, requires employees to work inordinately long hours without overtime for the attainment of set goals and thereby enables management to pay less per unit of time and reduces the total salary costs of the company. It has also been pointed out that the introduction of the annual salary system not only creates two groups of employees in an enterprise but also enhances the level of intra-company social disparity and reduces team work and morale. At issue also is the transparency of the evaluation process regarding the degree to which pre-arranged goals have been attained. While advocates of the performance model contend that the scheme is in line with globally accepted business practice, ‘Japanese-style’ management proponents maintain that it is predicated upon the principle of the survival of the fittest, a doctrine detrimental to the general wellbeing of employees. Even in the late 2000s, in the sphere of value orientation, the paternalistic ‘Japanese-style’ management model appears to have robust support among Japanese workers: national random surveys conducted by the Institute of Statistical Mathematics have consistently shown for more than half a century that ‘a supervisor who is overly demanding at work but is willing to listen to personal problems and is concerned with the welfare of workers’ is preferred to ‘one who is not so strict on the job but leaves the worker alone and does not involve himself with their personal matters.’19 Likewise, a larger proportion of the Japanese populace would prefer to work in a company with recreational activities like field days and leisure outings for employees despite relatively low wages, rather than in one with high wages without such a family-like atmosphere.20

It should be reiterated that the beneficiaries of lifetime employment, seniority-based wages and enterprise unionism have been limited in practice to the core employees of large companies, a quarter of the total workforce at most. Inter-company mobility and performance-based wage structures had been prevalent in small firms and among non-core workers, though neither was quite visible nor controversial during the high growth period because every worker’s labor conditions appeared to be improving at least on the surface.

The debate over the performance model flared up because it started affecting the elite sector; ‘Japanese-style’ management has never applied to small businesses which adjust their employment structure according to economic fluctuations, with workers moving from one company to another with considerable frequency. An increasing number of non-regular workers, those part-timers and casuals with no long-term employment base, are hired and fired depending upon performance and output. One should, therefore, examine the debate over the competing models of work with a conscious focus on the lower end of the labor-force hierarchy.

Cultural Capitalism: An Emerging Mega-sector

Culture has become big business around the world with advanced economies increasingly dominated by the information, education, medicine, welfare and other cultural industries that specialize in the world of symbols, images and representations. Japan’s capitalism has been at the forefront in this area by producing fresh value-added commodities in the face of growing competition from Asian countries to which the centers of industrial production had shifted. No longer the manufacturing powerhouse of the world, Japanese capitalism has carved out new and enormous markets through expertise in the worlds of software technology, visual media, music, entertainment, hospitality and leisure. In these fields, Japanese companies continue to hold comparative advantage and claim international superiority, thereby releasing a constant stream of cultural products into the global market and reshaping the Japanese economy.

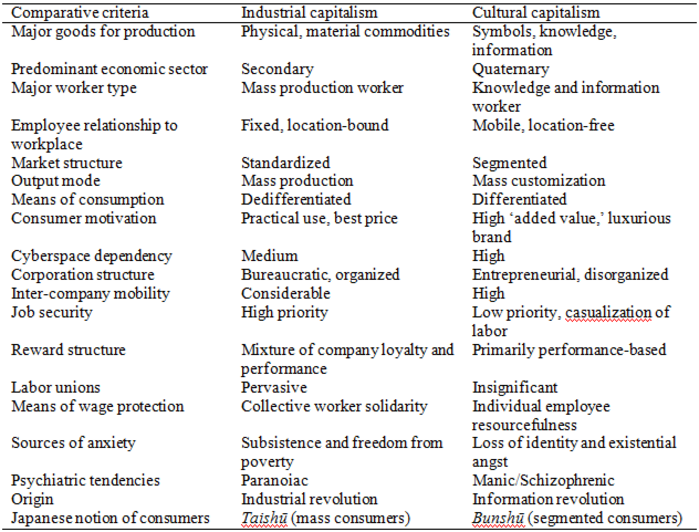

One may argue that Japan has now developed cultural capitalism, which relies upon the production of symbols, knowledge and information as the guiding principle of wealth creation and focuses upon cultural attractions and activities as the primary motivating factors underpinning consumption. The debate over ‘soft power’ and ‘Japan Cool’ has arisen in this context. To provide a map of the comparative features of emerging cultural capitalism as distinguished from conventional industrial capitalism, Table 2 contrasts the modus operandi of the two types of capitalism in existence today. It should be stressed that the features in the cells do not denote exclusive properties of each type but exhibit the relative points of emphasis of the two for comparative purposes.

As early as the 1980s, market analysts were quick to point out that the patterns of Japanese consumer behavior were becoming diversified in a fundamental way. Previously, manufacturers sold models standardized for mass consumption, successfully promoting them through sales campaigns and advertisements. Recently, however, this strategy has become ineffective as consumers have begun to seek products in tune with their personal preferences. They have become more unpredictable, selective, and inquisitive. The notion of the Japanese as uniform mass consumers does not effectively account for their consumer behavior patterns today. A consumer behavior study21 suggested the emergence of shōshū – individualized, divided, and small-unit masses – as opposed to taishū, the undifferentiated, uniform, and large-scale mass. The research institute of Hakuhōdō,22 a leading advertising agency, also argued that the notion of bunshū (segmented masses) would account for the behavior of consumers more effectively than the conventional view of them as a homogeneous entity. In short, cultural capitalism thrives with mass customization, the production of many different commodities tailored for specific focus groups, unlike industrial capitalism that is built upon the mass production of a small number of standardized goods. If industrial capitalism survives on the relative homogeneity of consumer lifestyles, cultural capitalism rests upon their differentiation. Mobile phones, for instance, are frequently revamped with different functions, designs and colors, fashioned to fulfill the distinct desires of particular and shifting demographics.

Contents of takeout box lunches sold to office workers at convenience stores are highly varied to satisfy the diverse tastes of youngsters, women, middle-aged men and other socio-economic groups.

Table 2: Patterns of two types of capitalism

Such differentiation of consumer motivations mirrors alterations in the criteria of class formation. Hara and Seiyama, leading experts in social stratification, argue that inequality has been removed in contemporary ‘affluent’ Japan as far as ‘basic goods’ are concerned, while the nation is increasingly stratified in pursuit of what they call ‘upper goods.’23 Absolute poverty was eradicated when the population’s subsistence needs were met. Almost every household can now afford a television set, telephone, car, rice cooker and other essential goods for a comfortable daily life. Virtually all teenagers advance to senior high school and fulfill their basic educational requisites. In the meantime, community perceptions of social stratification are becoming multi-dimensional. The different sectors of the Japanese population are increasingly divergent in their respective evaluations of status indicators. Some attach importance to asset accumulation, while others regard occupational kudos as crucial. Still others would deem quality of life the most significant dimension. In each sphere, what Hara and Seiyama call ‘upper goods’ are scarce, be they luxury housing, postgraduate education or deluxe holidays, with these expensive commodities being beyond the reach of many people. Thus, social divisions in Japanese society today derive not so much from the unequal distribution of commonplace and mundane industrial goods as from that of prestigious and stylish cultural goods.

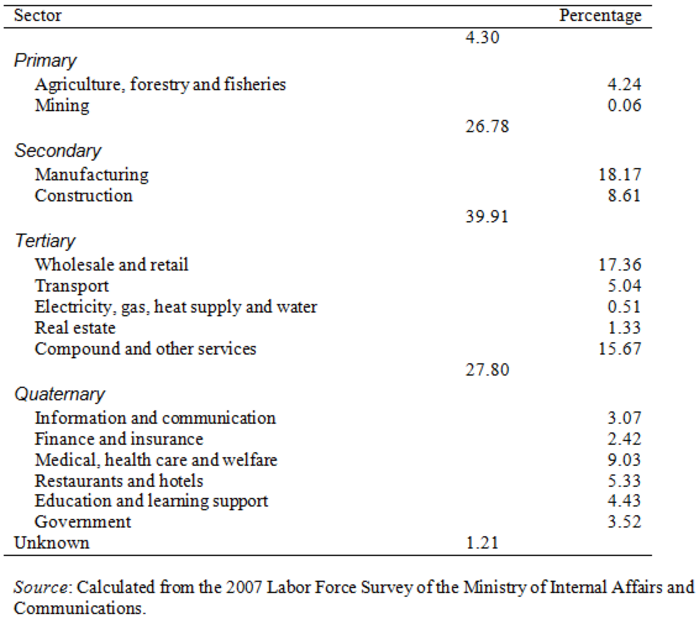

Table 3: Distribution of workers in four mega sectors

It is an established convention to divide economies into three sectors of activity: the primary sector (including agriculture and fisheries) which transforms natural resources into products, the secondary sector (comprising manufacturing and construction) which produces finished goods from the output of the primary sector, and the tertiary sector which offers services or intangible goods and encompasses industries ranging from retail, wholesale, finance and real estate to the public service. Given that some 70 percent of workers in Japan are now employed in the tertiary sector,24 this sector needs reclassification according to internal varieties. Specifically, the recent expansion of areas that make knowledge-based, informational and value-added products form what may be categorized as the quaternary sector which branches off from the conventional tertiary sector. Though no governmental statistics are based on such category, on a rough and conservative estimate, approximately one quarter of Japan’s workforce operates in this sphere, ranging from employees in the information and telecommunications industries, medical, health care and welfare sectors, restaurants, hotels and other leisure businesses to education and teaching support staff, and government workers. As Table 3 suggests, the number of employees engaged in the quaternary sector is on par with that of those in the manufacturing and construction industries that are typically classified as the secondary sector. These figures are admittedly very crude approximations.25 Nevertheless, broadly speaking, cultural workers undoubtedly predominate as much as industrial workers in the landscape of Japan’s workforce today.

In tandem with these domestic shifts, Japan is now seen internationally as a superpower in terms of cultural ‘soft power’ that exercises a significant influence around the world in various areas of popular culture, including computer games, pop music, fashion, architecture, not to mention manga and anime. In the field of education, the Kumon method which has spread across at least forty four countries and territories uses special methods to tutor children in a variety of subjects. In music, the Suzuki method is marketed as a unique and special approach to enhance musical talent. Even in sushi restaurants, Japanese cuisine techniques constitute the core of business activity.

Nintendo is now a household name around the world, and computer games made in Japan enjoy immense popularity. So do Sudoku puzzles initially actively commercialized in Japan. These developments reflect the sharp edges of the emerging international division of labor in which the production of cultural goods occupies a crucial position in advanced economies in general and Japanese capitalism in particular.

All this signifies that the knowledge-intensive skills that are based on exclusive patents, copyrights and intellectual properties take on increasingly profound significance and attach greater significance to the cultural dimensions of production.

Cultural capitalism goes hand in hand with cultural nationalism. Japan’s state machinery regards the expansion of its cultural capitalism as a global strategy to enhance the nation’s position in the international hierarchy. In particular, the popularity of Japanese cultural goods has a special meaning in Asia where competing historical interpretations of World War II still cause contention. Even though memories of the past and the cultural trade of the present are two separate dimensions, it is a part of the master plan of the Japanese state that the prevailing popular image of Japanese cultural commodities in Asia will aid Japan as a nation in gaining general acceptance in the region in the long run. The notion that Japan as the most advanced country in Asia should lead other nations in the region concurs with the worldview of the Japanese establishment, even though the idea sometimes conjures up the wartime Japanese ideology of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.

It is also worth noting here that an increasing number of workers in the cultural sector, if not all, can produce their commodities without being bound to a particular physical place of work. If industrial capitalism originated from the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth century, cultural capitalism exploded with the Information Revolution in the late twentieth century, accompanied by the sudden expansion of the internet and the proliferation of mobile phones. Cyberspace technology enables cultural workers to be de-localized, and this tends to facilitate the above-mentioned casualization of employment. At the same time, the creative expertise of cultural products can easily be copied without authorization and pirated inter-territorially. To confront the situation, the ‘Basic Law of Intellectual Properties’ was enacted in 2002 to safeguard not only Japanese patents but also the nation’s contents industry that produces original texts, images, movies, music and other creative data, while strict state regulation of cyberspace continues to be a near impossibility.

In this environment, workers become fragmented, with their work life becoming increasingly compartmentalized. Labor unions which used to be the bastion of worker solidarity have gradually lost membership and power, and individual employees attempt to defend themselves by being self-centered, resourceful and entrepreneurial. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Japanese are concerned less with the survival and subsistence issues that govern industrial capitalism and more with the precariousness of their sense of identity and reality, the existential issues that characterize cultural capitalism. This trend forms a backdrop against which people attempt to carve out a new form of community in expanding civil society.26

References

Asahi Shimbun ‘Lost Generation’ Shuzai-han 2007, Lost generation: smayou 2-sen mannin (The lost generation: straying twenty million). Asahi Shimbunsha.

Chiavacci, David 2008, ‘From class struggle to general middle-class society to divided society: Models of inequality in postwar Japan’, Social Science Japan Journal, vol. 11, no. 1: 5–27.

Chūō Kōron Henshūbu and Nakai, Kōichi (eds) 2003, Ronsō: Gakuryoku hōkai (Debate on the disruption of academic ability). Chūō Kōronsha.

Fujita, Wakao 1984, Sayonara, taishū (A farewell to masses). Kyoto: PHP Kenkyūsho.

Hakuhōdō Seikatsu Sōgō Kenkyūsho 1985, ‘Bunshū’ no tanjō (The emergence of segmented masses). Nihon Keizai Shimbunsha.

Hara, Junsuke and Seiyama, Kazuo 2006, Inequality amid Affluence: Social Stratification in Japan. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Ishida, Hiroshi 2010, ‘Does class matter in Japan?’, in Hiroshi Ishida and David H. Slater (eds), Social Class in Japan, London: Routledge, pp. 33–56.

Kenessey, Zoltan 1987, ‘The primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary sectors of the economy,’ Review of Income and Wealth, vol. 33, issue 4: 359–85.

Kōsei Rōdōshō (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) 2006, Heisei 18-nenban rōdō keizai no bunseki (Analysis of labor economics, 2006).

Kosugi, Reiko 2008, Escape from Work: Freelancing Youth and the Challenge to Corporate Japan. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Morioka, Kōji 2009, Hinkonka suru howaito karā (The impoverished white collar). Chikuma Shobō.

NHK Special ‘Working Poor’ Shuzai-han 2007, Working Poor: Nippon o mushibamu yamai (The working poor: the dicease that gnaws away at Japan). Popla-sha.

Satō, Toshiki 2000, Fubyōdō shakai Nippon (Japan: Not an egalitarian society). Chūō Kōronsha.

Shirase, Sawako 2010, ‘Marriage as an association of social classes in a low fertility rate society, Hiroshi Ishida and David H. Slater (eds), Social Class in Contemporary Japan. London: Routledge, pp. 57–83.

Tachibanaki, Toshiaki 2005, Confronting Income Inequality in Japan: A Comparative Analysis of Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Tōkei Sūri Kenkyūsho (Institute of Statistical Mathematics) 2009, ‘Kokumin-sei no kenkyū: 2008-nen dai 12-kai zenkoku chōsa’ (Studies of national character: the 12th national survey, conducted in 2008). Tōkei Chōsa Kenkyō Report.

Yoshio Sugimoto is Emeritus Professor of Sociology, La Trobe University and Director, Trans Pacific Press Pty Ltd

He drew on material from his Introduction to Japanese Society to prepare this article.

His Recent books include An Introduction to Japanese Society, third edition (2010) and The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture (2009).

Recommended citation:Yoshio SUGIMOTO, “Class and Work in Cultural Capitalism: Japanese Trends,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 40-1-10, October 4, 2010.

Articles on related subjects:

Nobuko Adachi, Ethnic Identity, Culture, and Race: Japanese and Nikkei at Home and Abroad

Stephanie Assmann and Sebastian Maslow, Dispatched and Displaced: Rethinking Employment and Welfare Protection in Japan

David H. Slater, The Making of Japan’s New Working Class: “Freeters” and the Progression From Middle School to the Labor Market

Recommended citation: Yoshio Sugimoto, “Class and Work in Cultural Capitalism: Japanese Trends,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 40-1-10, October 4, 2010.

Notes

1 This article is based on material drawn from An Introduction to Japanese Society, third edition (Cambridge University Press 2010) and submitted at the invitation of Japan Focus.

2 For an excellent analysis of the paradigm change, see Chiavacci 2008.

3 Satō 2000 initiated the debate.

4 Tachibanaki 2005 is one of the best studies in the area.

5 Shirahase 2010.

6 Tokyo Daigaku Kōhō Iinkai 2008. The data were gathered in 2007.

7 Japan’s relative poverty rate, an indicator of the percentage of low-income earners, was 14.9 percent in 2004, the fourth highest among the OECD’s thirty member nations, and rose to 15.7 percent in 2007. The relative poverty rate represents the percentage of income earners whose wage is below half of the median income.

8 See Tōkei Sūri Kenkyūsho 2009, Table 1.8.

9 See Ishida 2010.

10 The total index of structural mobility records a consistent upward trend throughout the postwar years. The agricultural population provides the only exception to this propensity, showing a consistent downward trend. The total index arrived at its peak in 1975, reflecting a massive structural transformation which transpired during the so-called high-growth period starting in the mid 1960s.

11 Morioka 2009.

12 Satō 2000. Some experts dispute this thesis. See, for example, Hara and Seiyama 2005, pp. xxiii–vi.

13 Chūō Kōron Henshūbu and Nakai 2003.

14 The Labor Force Survey conducted in 2008 by the Ministry of Welfare, Labor and Health.

15 See NHK Special 2007.

16 For details, see Kosugi 2008.

17 Asahi Shimbun ‘Lost Generation’ Shuzai-han 2007.

18 Kōsei Rōdōshō 2006. The figures are calculated from data collected in 2002.

19 Tōkei Sūri Kenkyūsho 2009, Table 5.6. In the 2008 survey, 81 percent support the former type and 15 the latter.

20 Tōkei Sūri Kenkyūsho 2009, Table 5.6b. Both in 2003 and 2008, the figures were 53 percent versus 44 percent.

21 Fujita 1984.

22 Hakuhōdō 1985.

23 This is a major theme of Hara and Seiyama 2005. See pp. 164–7 in particular.

24 Labor Force Survey in 2007, conducted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

25 The so-called ‘compound’ and ‘other’ service industries include cultural enterprises, such as ‘political, business and cultural organizations’ and ‘religion.’ Some researchers of the quaternary sector – such as Kenessey 1987 – include ‘real estate’ in this sector. Our approximation here is quite conservative, and we simply wish to show that the quaternary sector now forms an independent, expanding and sufficiently large sector in its own right.

26 The thesis is examined in Chapter 10 of the book.