US Bases, Japan and the Reality of Okinawa as a Military Colony

Yoshida Kensei

Translated by Rumi Sakamoto and Matt Allen

On June 24, 2007, two US Navy minesweepers entered the small Sonai port in Yonaguni island, the westernmost Japanese island near Taiwan, on a ‘good-will visit and crew R and R’. Okinawa prefectural governor Mr. Nakaima had stated that the ‘US Navy warships should use the designated ports such as White Beach and Naha Military Port and should not use civilian ports’. He asked the Commander, US Naval Forces, Japan to voluntarily refrain from entry into Sonai port; Mr. Hokama, the mayor of Yonaguni town and its residents had also expressed opposition, but they were ignored. According to the Division Chief, North American Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who visited the Yonaguni town office prior to the vessels’ visit, ‘due to the provisions of the SOFA (Status of Forces Agreement), the heads of local public bodies have no right to reject the US minesweepers’ visit to their ports. There is no choice other than to accepti their entry into the port.’

In May 1998, the Fukuoka High Court’s Naha branch dismissed the request of residents living near Kadena Air Base who suffered from noise pollution and tremors from early morning till the middle of the night to ban US military aircraft taking off and landing, despite accepting the fact that the aircraft caused damage. The ruling was based on the judgement of the Supreme Court that Kadena Air Base had been ‘offered’ to the US through the Japan-US Security Treaty and SOFA, and therefore the residents did not have a right to demand limitation of the operation of the US military flights there.

These two examples reveal that in Okinawa, which is supposedly a part of Japan, US military intentions prevail over the wishes of Japanese residents, and that the Japanese constitution and laws do not apply in Okinawa. Not only in Okinawa but also in Japan, US military bases, US military planes and warships that arrive and leave from these bases, US military personnel and civilian employees who belong to the bases, and even civilian ports if the US needs them, all fall under the principle of extraterritoriality; that is, they are beyond Japanese law. Okinawa, which hosts US military forces (USF) and US bases, can, therefore, be called a ‘military colony’ of the US. I would like to begin this article using this perspective to examine the reality of the USF in Okinawa, the history of military bases in Okinawa, the role of these bases within US international policy, and the nature and future of US bases in Okinawa.

US bases are an extension of the US

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the USF and bases in Japan are governed by the SOFA, which ‘regulates the USF’s use of facilities and areas, as well as the status of the USF. This is to ensure effective operations of the USF maintained in our country in order to achieve the goal of the Japan US Security Treaty’. However, although Japan accepts the stationing of the USF in Japan and provides the bases, the USF Japan, military personnel and civilian employees are basically an extension of US sovereignty and the US military. Therefore, the USF, military personnel and civilian employees are subject to a military chain of command with the US President at the apex and below him the Secretary of Defense, Commander of the Unified Commands (I will discuss this in more detail later), the commander of the USF in Japan, the commander of Marine Corps Forces in Japan (and concurrently the commander of III Marine Expeditionary Forces) in Okinawa, and commanders and senior officers at each base. They are also bound by the US Constitution, Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), regulations within each unit, commanders’ orders, or precedents within the USF (although there are some cases where the US Constitution and laws have not been observed in Okinawa). Okinawa thus coexists with the US with only a wire fence separating them. Many base-related problems arise from military planes, transport planes, helicopters that take off from these bases for training and combat, toxic substances the USF uses, and (some) service members and civilian employees who hit the town nightly.

The USF differ greatly from ordinary Japanese society. There are some cases, such as leaking official secrets or rape, where a court martial is stricter than Japanese courts; but if a US service member commits other sex crimes or manslaughter due to drunk driving, depending on the status, distinguished service, and wishes of the complainant, in order to protect the honour of the military and the person concerned, or in order to avoid complex legal procedures, it is possible to allow them to voluntarily retire instead of being dishonourably discharged or imprisoned. It is also possible for a criminal or a gang member to join the military forces through the ‘waiver’ system. Because of the difficulty in recruitment, some foreigners are inducted in the armed forces in exchange for the promise of US citizenship. The military regime is arduous, and many soldiers depend on alcohol to deal with stress from base discipline and combat training. Perhaps such a ‘military culture’ forms the background for the crimes around the bases. The US Department of Defense stated that there were 2,688 incidents of sexual violence by US soldiers (of which 60% were rape cases) in the year starting September 2006. However, given the nature of sexual violence, in which victims often remain silent, this could be just the tip of the iceberg.

Despite Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ insistence that USF and US service members ‘must respect Japanese laws and pay appropriate attention to public safety, as required by SOFA’, Japanese police power and jurisdiction do not apply to the bases. Even if there is concern regarding environmental pollution, Japanese Ministry of Environment or local municipalities cannot enter a base to investigate. There is no obligation for the US to return the land in its original condition when the bases are closed and returned to Japan (it has such an obligation within the US). Even with incidents outside the bases, if the service member involved was ‘on duty’, the case falls under US jurisdiction. With ‘off duty’ incidents, too, if the US arrests the suspect, they will keep the detainee until the Japanese side presses charges, thus slowing down important early stage investigation. Military personnel and US civilian base employees in Okinawa are treated differently from ordinary foreigners. They do not have to show their passports for entry into and exit from the country, nor do they have to register as residents in Japan. Even if they live outside the bases, right next to ordinary citizens, they are not required to register with local Japanese authorities the name of their unit, their rank, gender, age etc. If Japan has no information on those to whom SOFA applies, how is it to ensure that they adhere to SOFA? With USF exempted from conforming to the Japanese Constitution and laws, it is unsurprising that service members respect neither Japanese custom and law, nor the SOFA.

On May 1, 2008, Haisai, a PR pamphlet of the Okinawa Defense Administration Agency, carried the following announcement. ‘Okinawa Defense Administration Agency, based on the SOFA, provides compensation for any damage caused by accidents or incidents within our administrative area due to illegal actions by the USF and its members etc. (soldiers, civilian employees). Should you suffer damage, please contact us at the address below as soon as possible after the accident.’ Thus a local agency of the Japanese government even provides compensation for damages caused by US service members and civilian employees.

When a US transport helicopter from Futenma Marine Corps Air Station crashed at the Okinawa International University campus (2004), despite this taking place outside the base, the US military acted as if Japan was its occupied territory and closed off the accident site, thus disrupting the work of Japanese police and fire fighters. On top of this, it was the Defense Agency’s Naha Facilities Administration Agency (now the Ministry of Defense, Okinawa Defense Administration Agency) that repeatedly apologized over the accident and paid compensation for the damage to the university.

Futenma Base in crowded Ginowan

The US freely decides what weapons and bombs will be brought into the bases, what training is conducted, and which wars to fight. Japan upholds the three non-nuclear principles of ‘nonpossession, nonproduction, and nonintroduction’. This also applies to Okinawa. The reality, however, is unclear. Japanese government officials cannot enter bases to confirm whether there are nuclear weapons or not.

Concerning the Japanese SDF’s dispatch to Iraq, there was no reporting of the Nagoya High Court’s judgment in mid April that Air Self Defense Force (ASDF) activities ‘contain activities that breach Article 9 of the Constitution’, namely, that the disparth of ASDF to Iraq was unconstitutional. Article nine states that ‘Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes’. From the perspective of Okinawa, however, Japan has already participated in many wars by way of the USF in Okinawa and Japan, including the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and attacks on Iraq and Afghanistan. In Iraq and Afghanistan, the US Air Force and Marine Corps from Okinawa have participated in combat, transport, and intelligence. The number of Iraqi civilian deaths exceeded 150,000 in the first 3 years of the war according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Military colonisation that has lasted for 65 years

It has been 65 years since the ‘militarisation’ of Okinawa. The bases were initially built by the Japanese government (Imperial Headquarters). In order to defend the ‘imperial land’ (mainland Japan) from the US army moving north, the Japanese government dispatched the 32nd Army to Okinawa. Using the slogan of ‘voluntary labour service’, it also mobilised many residents including youth to build and repair numerous airfields such as the Naha (Koroku) Naval Airfield, Kadena Airfield, Yomitan Airfield, Makiminato Airfield, Yonabara Airfield. Three airfields were built on both Iejima and Miyako Island. In addition to the 32nd Division’s Underground Headquarters directly under Shuri Castle in Naha, the Japanese military also entrenched itself in many other locations.

The US military planned to use Okinawa to launch attacks on mainland Japan. Therefore, after declaring that the Ryukyu Islands and their residents were separated from the administrative control of Japan and placed under US military government, the US repaired and reinforced the destroyed airfields, ports, roads and bridges while attacking the Japanese Army. They occupied villages, fields, rice paddies and beaches, using them as barracks, repair facilities, and storehouses. In the fierce battle, a total of 200,000 Japanese and Americans lost their lives. The number of civilian deaths, excluding soldiers and civilian employees, was close to 100,000.

After Japan surrendered, the US military retained possession of bases in Okinawa and enlarged or strengthened some. The first opportunity to do so occurred during the war and the immediate postwar period. The second opportunity to expand followed the deterioration of the ‘Far East’ situation: the deepening of the Cold War that came with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and the outbreak of the Korean War; tensiosn over the Taiwan Strait; and the Vietnam War. In all these cases, bases were maintained and strengthened without regard for the residents of Okinawa. Residents’ opposition was ignored. It is a clear contradiction that the US on the one hand holds up the ideal of ‘freedom and democracy’ and ‘regional security’ but on the other hand in Okinawa it overlooks residents’ voices, their requirements for a peaceful life, and their human rights.

In the early occupation, the US enclosed huge areas without the consent of the landowners and without paying compensation. The requisition and use of such land as military bases is a violation of the Hague Convention’s Laws and Customs of War on Land (1907), which prohibits confiscation of private property or pillage, the Cairo Declaration (1943), in which Great Britain, the US, and other nations pledged no territorial expansion, and the Potsdam Declaration (1945), which established democracy after Japan’s surrender and withdew most of the occupying forces. It is unclear whether the US had planned from the outset to occupy Okinawa for an extended period; but Louis Johnson, the Secretary of Defense, when he visited Okinawa in June 1950 as tensions mounted over the situation in the Far East, stated that in order to make Okinawa an impregnable fortress, the US ‘will build permanent facilities that will withstand typhoons and other destruction.’

Article 3 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which Japan signed with the US and other countries in 1951 (effective 28th April 1952) stipulated: The US proposes to the UN that the Nansei Shoto including Ryukyu, is ‘placed under its trusteeship system’ with the US as the sole administering authority; Japan will concur with any proposal of the US. However, during the period between the proposal and its approval, the US will have the right to exercise ‘all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction’ over these islands, sea territory and their inhabitants.

Article 3, too, possibly violates the aforementioned Hague Convention’s Laws and Customs of War on Land and the Potsdam Declaration. At any rate, for 20 years since then, the US placed Okinawa under the jurisdiction of the US Secretary of Defense (represented locally by the High Commissioner) based on Article 3. Okinawa thus became a US military colony. Okinawan fiercely protested against the US military’s requisition of land by a sit-in and other means; however, the US mobilised its forces, using ‘bayonets and bulldozers’ to move them off their land.

In January 1954, President Eisenhower stated in his annual State of the Union message to Congress: ‘We shall maintain indefinitely our bases in Okinawa.’ From around that time, the USF began to call Okinawa a ‘Keystone of the Pacific.’ In December of the same year, nuclear weapons were placed in Okinawa, their number peaking at 1,200 in the 1960s (Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Nov/Dec 1999). According to a recently released classified US Air Force document, at the time of 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis, the US Pacific Air Force had a strategic plan to deploy nuclear weapons against mainland China using a bomber from the Kadena Air Base.

In 1962, the US Army’s former 267th Chemical Service Platoon in Alaska was reactivated and stationed at the US Army Depot in Okinawa. In 1965, it became the 267th Chemical Company and was assigned to the 196th Ordinance Battalion, 2nd Logistics Command. In 1968, a toxic gas leak at the Chibana ammunition storage facility of the 2nd Logistics Command poisoned 24 US service members. The US Department of Defense admitted that it was storing highly lethal chemical weapons such as sarin and mustard gas, and stated that it was relocated chemical munitions to Johnston Island in 1971 (Operation Red Hat). In the early 1960s, the US sprayed Agent Orange containing highly toxic dioxin in the training area in northern Okinawa. Nuclear weapons were reportedly removed by 1971, but since US policy regarding the storage of nuclear weapons is to ‘neither confirm nor deny’, there is no way of knowing the truth.

In 1972 Okinawa finally reverted to Japan and came under the Japanese Constitution. However, the wish to abolish the US bases in Okinawa, or at least to reduce their size to those on the mainland, was not granted. When Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon agreed to Okinawa’s reversion to Japan in November 1969, the precondition was that it not be detrimental to the ‘security of the Far East including Japan’. In order to fulfill this condition, both governments applied the Japan-US Security Treaty and SOFA to Okinawa ‘without any modification’. According to Headquarters USF: ‘the return and joint use of US facilities and areas continued during the 1970s, especially in Honshu. The 5th Air Force transferred its fighters etc. from the main islands to the Kanto Plain area. With that, support forces and military housing areas were closed, and Army supply houses were also reduced or closed. In addition to the return of facilities, there was also a huge cutback of Japanese employees of the USF Japan.’ The US military bases in mainland Japan were thus substantially reduced; but the USF in Okinawa remained essentially the same as in the pre-reversion era. Therefore, the proportion of the USF in Okinawa in relation to the country as a whole increased. Okinawa became the pillar that supports the Japan-US Security Treaty. Under Japan-US SOFA, Okinawa was turned into a military colony of both Japan and the US.

Okinawa in US International Strategy

In 1975 the US withdrew from Vietnam and in 1989 the Cold War ended. However, the US neither withdrew its forces from Okinawa nor closed the bases. Even though Okinawa was under Japanese administrative sovereignty, it continued to be a military colony with the predominance of the USF.

Since then, the 1991 Gulf War, multiple simultaneous terrorist attacks iin 2001, the North Korean nuclear threat, and China’s expanding military budget, the US had new pretexts for building up its military forces and maintaining the USF in Okinawa.

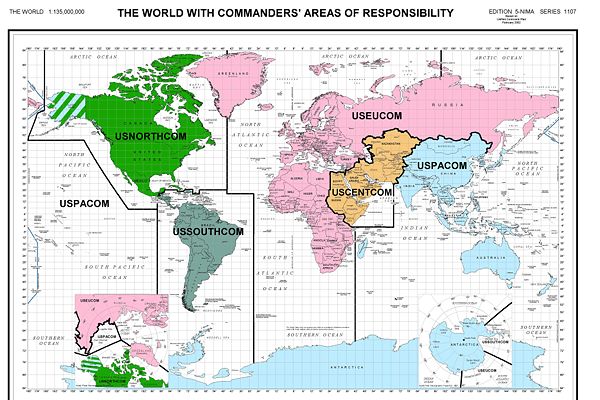

Since World War II, the US has rationalised and modernised the armed forces. Central to this process has been Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) both in and outside the US, and the functional reorganisation of the armed forces. In particular, aiming at constructing a post-Cold War new world order, the US advanced the Unified Combatant Command (area army) system. The USF in Japan including Okinawa belongs to the Pacific Unified Command based in Honolulu. Its area of responsibility covers the west coasts of South and North Americas (including armed forces stationed in Alaska and Hawaii, but excluding the area within 500 nautical miles of the US mainland and the West coast of South America, which comes under the responsibility of the US Southern Command), most of the Indian Ocean except the Middle East, and more than half the Arctic Ocean and the Antarctic Ocean. Located in this area, which covers more than half the surface of the world, are the world’s military superpowers: the US, China, Russia, as well as India, Japan, Korea, North Korea, and Australia, as well as major US trading partners. This area is critical for the US strategically and economically. The Command system that covers the whole earth and stretches even to outer space, shows that the US regards itself ‘the world’s sheriff’.

The US national defense expenditure for carrying out its international strategies, partly because of the rising cost of the Iraq War, reached $700 billion (48% of the world’s total national defense expenditure) in 2008. This is six times higher than China’s national defense expenditure in the same year, which was $120 billion (8%) (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). US national defense expenditure exceeds, for example, the GDP of Turkey or Taiwan (2007 estimate), and is more than 350 times the United Nations’ normal budget.

The new role the US has allocated to the USF in Okinawa international strategies was to deal with the area that the US Department of Defense has called ‘the arc of instability’ in the 2001 ‘Review of the National Defense Strategy’, namely from North Korea via South East Asia to the Middle East and the African coasts. Okinawa has turned into a military base for the ‘state of perpetual preparedness for war’ watching over the ‘arc of instability.’

Partly because of this, the size of the USF on the small islands of Okinawa is extraordinary compared to those in other countries. As of the end of September 2006 the USF in Okinawa consisted of 890 service members in the Army, 1,690 in the Navy, 13,840 in the Marine Corps, and 7,080 in the Air Force, for a total of 23,140. (‘USF and SDF bases in Okinawa’ Compiled Statistical Resources, March 2007)). Indeed, Okinawa hosts 69% of all USF in Japan (33,450), 53% of the Air Force, and as much as 94% of Marine Corps personnel. If we add to this figure the 1,333 US civilian employees and 20,000 family members, more than 43,000 people who are associated with the USF are stationed in Okinawa.

If we look at the USF in other members of NATO, Turkey hosts 1,590 US service members, Belgium 1,330, Spain 1,290, Portugal 830, the Netherlands 580. These numbers are much smaller than in Okinawa, mere remote islands of Japan. Only 55 are stationed in France. Even in the UK and Italy there are only about 10,000. In Australia, an important ally of the US in Asia Pacific, only 140 are stationed. 120 US service members are in Singapore; 90 in Thailand, and 95 in the Philippines. In the Pacific Ocean, other than in Hawaii, there are only 2,800 in Guam, which is an unincorporated territory of the US, five in Wake island and two in Samoa. 140 in Canada across the US border, 20 in Mexico, and 400 in Honduras.

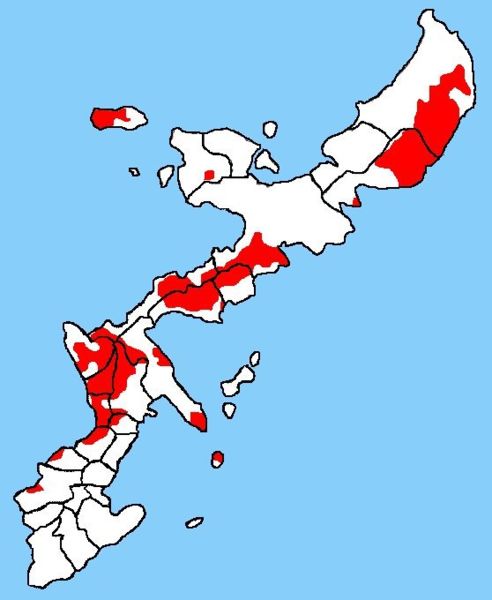

Japan has about 310 square kilometers of facilities exclusively used by the USF with an overwhelming proportion of US bases concentrated in Okinawa. According to the Ministry of Defense, as of 1st January 2008, 74.23% of the total area of US military facilities in Japan (229 sq. km) are located in Okinawa. The proportion of the land area occupied by the US bases on mainland Japan is 0.02%; in Okinawa prefecture, 10.08%. The second largest area of the US military facilities is in Aomori prefecture (24 sq. km; 7.69% of the prefectural land), third, Kanagawa (18 sq. km; 5. 91%), and fourth, Tokyo (13 sq. km; 4.28%). None of these comes anywhere close to Okinawa. It would not be wrong to say ‘the USF Japan means the USF Okinawa, and the US bases in Japan means the US bases in Okinawa.’

Moreover, the bases are concentrated on Okinawa Main Island (including Iejima and Kumejima), where the proportion of land area occupied by the US military facilities is as high as 19% (excluding the huge sea area and airspace the USF use as training grounds etc.) These figures are in fact smaller than what they were before reversion, when US military bases took up 14.8% of the total land area of Okinawa prefecture and 27.2% of Okinawa Main Island. The central part of the Main Island has the highest proportion of bases (25%): 83% of Kadena, about 60% of Kin, 54% of Chatan, 51% of Ginowan, and 45% of Yomitan are occupied by bases. In Kunigami, in the forested area in the northern end of Okinawa Main Island, the bases occupy 23% of the land area, or 45 square kilometers, which is the largest area of bases in any one city or village.

The Northern Training Area, Camp Schwab, Camp Hansen, Red Beach and Blue Beach in Kin, Henoko Ordnance Ammunition Depot, Iejima Auxiliary Airfield, Yomitan Auxiliary Airfield, Futenma Air Station, Makiminato Service Area, Camp Courtney, Camp McTureous, Camp Zukeran … many of these are for the Marine Corps because the core of the USF in Okinawa is the Marine Corps, which are combat units.

Base facilities include jungle warfare training areas, airfields, flight training fields, firing ranges, bombing practice areas, urban (anti-terrorism) training facilities, landing training grounds, harbours, ammunition depots, fuel storage, communication facilities for espionage prevention, barracks, and welfare facilities … There are also urban residential streets inside bases that are equipped with high rise apartments, shopping malls, schools, entertainment facilities, churches, gyms and restaurants.

The varied goals of the USF in Okinawa are varied, including military training (Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps), storage of weapons and ammunitions, repair/maintenance (supply), command, prevention of espionage, information gathering, storage and supply of fuel, medical care, administration, accommodation, rest and recreation. They are not limited to training and providing logistical support. As the repeated dispatches of the mostly Marine Corps and the Air Force to Iraq and Afghanistan from Okinawa has shown, and as the US Marine Corps in Okinawa states, the USF in Okinawa is a battle deployment corps under ‘perpetual preparedness for war’. Okinawa once possessed the Nike Hercules, an interceptor missile, and in 2007, the Patriot, a ground-to-air guided missile, was newly placed in the 1st Battalion, 1st Air defense Artillery Regiment at Kadena Air Base.

The excessive concentration of the USF and US military bases in Okinawa has created different perceptions of the US bases in the Japanese mainland and on Okinawa. This is why many Japanese citizens can ignore various problems arising from the US bases on Okinawa and adopt an attitude of ‘it’s none of our business’.

Special Action Committee on Okinawwa (SACO) Agreement and after

Consider another question: Will Okinawa continue to be a military base? When the US returned Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty, it returned Naha Airport, Yogi Fuel Depot, Motobu Auxiliary Airfield , Ishikawa beach, parts of Camp Schwab and Camp Hansen. Naha Airport, which had been a US Air Base, became a civil airport; but Naha Port is still under the control of the USF. After reversion, Naha Air and Naval Support Facilities were returned and developed as residential and commercial areas, while Hanby Airfield was turned into Mihamamashi (Amerikamura); Awase Communication Facility, which had extended over today’s Okinawa city and Nakashiromura, was mostly turned into a residential area and an athletic park; Makiminato American residential area that spread over the hill behind Naha city was reborn as Naha’s new downtown area (Omoromachi). However, while 60% of the US bases on mainland Japan was realigned and reduced since 1972, in Okinawa the percentage stopped at 16%. The wish of the residents to reduce the US bases in Okinawa to the same level as the mainland was betrayed, and Okinawa remained the ‘keystone’ of the USF.’

A major change took place in 1995, when a school girl was raped by US soldiers. This intensified anti-base public opinion in Okinawa. In the same year, the Japanese and US governments established the Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) in order to ‘reduce the burden placed on Okinawan people, and by doing so to strengthen the Japan-US alliance’. Agreement was made on the first significant return of bases (11 facilities) in Okinawa by December 1996. This led to the termination of live fire artillery training over Prefectural Route 104, measures for reduction of aircraft noise levels, revision of SOFA, attachment of number plates for USF official vehicles, and public reports on US military aircraft accidents. It also promised the return of the land used by 11 facilities (50 sq. km; 21% of the total land area occupied by the US bases in Okinawa) by 2008. However, even if all these areas are returned, the percentage of US bases in Okinawa out of all the land area of facilities exclusively used by the USF will change from 74% to 70%, leaving Okinawa overwhelmingly dominated by US bases. Moreover, the precondition of the return of seven facilities including the Futenma Air Station, is the relocation of these facilities. Mostly this meant ‘relocation within the prefecture’. Realignment and reduction have experienced major delays. Especially, the plan to move Futenma Marine Corps Air Station, where a helicopter crashed during training in 2004, to Henoko, Nago City in the Northern Pacific coast has ground to a halt after more than 12 years has passed since the agreement was made. Despite Governor Nakaima’s insistence that Futenma Air Station be ‘closed’ until relocation, training and mobilisation to the Middle East have continued; the residents in the area have been left with noise pollution and anxiety. Relocation of Futenma to Henoko, which is close to Camps Schwab and Hansen, will be convenient for the Marine Corps, but for the local residents it means new base pollution. The effect of the relocation on the dugong (a natural treasure that is close to extinction) and other creatures is another concern.

Since then, Japan and the US agreed on the SACO Interim Report in October 2005, and the Final Report was made public on May 1, 2006. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs calls it a ‘US-Japan roadmap for realignment’. It was decided that by 2012, the US will relocate 8,000 Marines and 9,000 family members from III Marine Expeditionary Force to Guam, and fully return five facilities located South of Kadena Base (Camp Kuwae, Makiminato supply area, Futenma Air Station, Naha Port facilities, Army oil storage facility), and part of Camp Zukeran. However, the Marine relocation to Guam (whose cost is to be born by Japan) depends on the relocation of Futenma Air Station within Okinawa, and the completion of the preparations for receiving them in Guam. Also, a precondition for the integration of the facilities and return of land south of Kadena is the completion of the Marine relocation to Guam. In short, there will be no relocation to Guam or a return of facilities until the Futenma Base relocation is complete.

The future of the USF in Okinawa

The crux of the SACO agreement was that while some facilities will be returned, the ‘function’ of the bases will be maintained by relocating them to alternative sites in Okinawa (or in Japan). On the one hand, aiming at increasing ‘interoperability’ of the USF and SDF, bilateral training and shared use of the bases have increased. A new urban warfare training facility has been built in Camp Hansen, and a ground-to-air Patriot guided missile system has been placed in Kadena. The purpose of the reorganisation of the USF Japan seems to be to incorporate the SDF into US international strategy, to expand the scope of the Japan-US Security Treaty (Japan-US Alliance) from the ‘Far East’ to the world as a whole, and to make full use of the already-existing bases in Japan, including those in Okinawa.

Other factors that influence the prolonged stationing of the USF is Japan’s ‘sympathy budget’ that far exceeds any other country’s US base budget, as well as the Okinawan economy’s dependenc on the bases. Japan’s contribution towards the cost of the stationing of US bases, which the US calls ‘host nation support’, consists of direct support (Japanese employees’ salaries, land rents, housing, utilities, relocation costs of training facilities – all added to the annual budget) and indirect support (tax waivers, road tolls and port use fees etc.). Every year, Japan’s financial support far exceeds the total of such support by NATO member nations, including Germany, Italy, and the UK. (The total amount of support by the 18 NATO member nations other than the US in 2002 was $2.5 billion or ¥300 billion; Japan’s support was $4.4 billion or ¥530 billion). Japan is one of the military superpowers of the world along with the UK, France, and China, with a defense budget of $44.3 billion. Japan’s ‘sympathy budget’ provides 75% of the total costs of the USF stationed in Japan (The NATO total is 27%, of which 97% is indirect contributions).

Part of the contribution comes back to the Okinawan economy in the form of land rents, salaries, material purchases, construction work etc. In addition, cities, towns, and villages that host US bases can claim from the Japanese state base-related expenses such as noise prevention measures, fishing industry compensation, and other subsidies and grants. The cities, towns and villages that receive the relocated bases will receive new reorganisation subsidies from the government. Okinawa has a very low proportion – about 30% – of independent revenue such as prefectural taxes. For the rest, it relies on reallocating local taxes and national Treasury disbursement; in addition, in such places as Kin, Ginowan, Onna, and Kadena, base-related revenue accounts for more than 20% of total revenues. The long-term presence of the bases has hindered Okinawa’s autonomous economy (the bases did contribute to the civil engineering and construction business, food and drink industries and supply industries). And Okinawa’s reversion to Japan led to the maintenance of infrastructure such as roads and public facilities. However, neither laid a foundation for long-term autonomy such as manufacturing industry, and Okinawa has fallen into the pathology of the ‘carrot and stick’ ideology the Japanese government set up.

In order for Okinawa to escape from its ‘military colony’ status, it is necessary to break free from this structure; it will not be easy. We need to reduce the importance of the bases by nurturing talented people and building up facilities in areas such as IT, medicine and care, by exchanges with neighboring countries, attracting investments, and further promoting tourism, agriculture, fisheries, and trade, taking advantage of Okinawa’s geographical uniqueness and nature. We should not simply see ourselves as victims of the Battle of Okinawa and the US bases, but think about the reality that the bases are supporting wars; then we will not be so eager to accept land rents or subsidies. If the bases are returned, there will be less danger of crash accidents, less noise pollution, fewer sex crimes and other incidents involving US soldiers. Not only will we reduce our association with wars (war cooperation), but base sites can be turned into housing areas, commercial or industrial areas, parks, or education/research areas. Revitalisation of the community will bring about far more income and revenue than the current base-related revenue, which has benefitted a limited number of landowners, businesses, cities, towns, and villages. Since the realignment of US bases throughout the world has been decided by the US, we cannot deny the possibility that one day the US will suddenly decide to reduce or withdraw its bases from Okinawa. To avoid being caught by surprise when that happens, Okinawa (Japan) needs to practice its sovereignty and prepare for that occasion.

The Japanese preconception that Okinawa equals US bases needs to be changed. If the Japanese nation considers the stationing of the USF and the US bases necessary, instead of forcing an excessive burden upon Okinawa, bases should be distributed throughout the country. It makes sense to do so from the perspective of national defense, too. Furthermore, the Japanese nation needs to examine the SOFA and the USF reorganisation from the standpoint of a sovereign nation. If we leave things as they are now, the SDF may become incorporated into the USF, and Japan’s defense policy integrated into the US international strategy, leaving Japan with nominal sovereignty. Finally, forcing the burden of the bases on Okinawa, while neglecting Okinawan people’s voices, is simply anti-democratic.

Yoshida Kensei was born in Itomanshi, Okinawa. A graduate of the University of Missouri, he was a professor at Obirin University in Japan until his retirement in 2006. He has authored a number of books on Okinawa, including Okinawasen – beihei wa nani o mita ka 50 nen go no shogen (Sairyu-sha), Senso ha peten da: batoraa shogun ni miru Okinawa to Nichibei chii kyotei (Nanatsumori shokan), Gunji shokuminchi Okinawa (Kobunken). He published this article in Gunshuku Mondai Shiryo (Materials on Arms Reduction) in July 2008.

Rumi Sakamoto is Lecturer in Asian Studies at Auckland University and a Japan Focus associate. Matt Allen teaches Asian history at the University of Auckland and is a Japan Focus associate. They are the coeditors of Popular Culture and Globalisation in Japan. They translated this article for Japan Focus. This condensed translation is published at Japan Focus on August 19, 2008.