Assessing the Nishimatsu Corporate Approach to Redressing Chinese Forced Labor in Wartime Japan [Japanese and Chinese texts available]

中国人強制連行・西松建設(広島・安野)訴訟後の和解について

Kang Jian, Arimitsu Ken and William Underwood

Introduction: Wartime forced labor and the future of Japan-China-Korea Relations

WILLIAM UNDERWOOD

The Nishimatsu Settlement Controversy

Xinhua News Agency reported in October 2009 that Nishimatsu Construction Co. “secured a reconciliation” by voluntarily agreeing to compensate Chinese victims of wartime forced labor in Japan, after resisting the redress claim for more than a decade. But questions have arisen regarding the content of the settlement, and whether it might foreshadow greater Japanese willingness to address past injustices. (The Japanese text of the settlement is available.)

In the out-of-court pact finalized on October 23, Nishimatsu Construction Co. agreed to set up a trust fund of 250 million yen, or $2.5 million (based on an exchange rate of 100 yen per dollar). The money will be used to compensate the 360 Chinese men who were forcibly taken to Hiroshima Prefecture in 1944 to build a hydroelectric power plant at Nishimatsu’s Yasuno worksite—or their families, since most of the workers have already died. The amount breaks down to about 690,000 yen ($6,900) per worker, but the trust fund must also provide for erecting a memorial in Japan, holding memorial ceremonies and conducting historical investigations. Nishimatsu apologized as well.

Post-settlement press conference in Hiroshima

Building on research begun by Japanese community activists, five survivors of forced labor at the Yasuno site sued Nishimatsu and the Japanese government in 1998, seeking apologies and compensation of 5.5 million yen ($55,000) each. The Hiroshima District Court rejected the claim in 2002, but two years later the Hiroshima High Court reversed that decision and ordered Nishimatsu to pay damages in full. The company appealed to the Japan Supreme Court, which ruled in 2007 that the treaty that restored Japan-China ties in 1972 extinguished the right of Chinese citizens to file war-related lawsuits against the Japanese state or Japanese firms. Yet the top court also stated that the defendants had jointly operated an illegal forced labor enterprise and measures to repair the plaintiffs should be expected.

The Nishimatsu Yasuno Settlement represents the response of the corporate defendant; the Japanese government has made no move toward reconciliation. At post-settlement public meetings in Hiroshima and China’s Shandong Province, elderly forced labor survivors and family members were depicted in media reports as well satisfied, speaking of personal closure and Chinese-Japanese friendship. Other participants in the Chinese forced labor redress movement, however, are more critical of the accord.

Beijing attorney Kang Jian dissects the Nishimatsu Yasuno Settlement in the first article below, calling it an insincere agreement devoid of accountability and appropriate compensation that cannot bring about authentic reconciliation. A prominent member of the All China Lawyers Association, Kang has been actively involved in most of the Chinese forced labor suits in Japan, from assisting with the initial selection of plaintiffs to making regular appearances in Japanese courtrooms. (See her previous article in The Asia-Pacific Journal on the eve of the Japan Supreme Court’s decision in the Nishimatsu case.) Kang continues to work closely with the Japan-based Lawyers Group for Chinese War Victims’ Compensation Claims, which since 1995 has litigated dozens of lawsuits in Japan on a pro bono basis.

The Lawyers Group, in fact, is now in the final stages of negotiating a second compensation agreement with Nishimatsu Construction Co. stemming from forced labor by 183 Chinese at its Shinanogawa worksite in Niigata Prefecture. Nishimatsu presumably considers the recent Yasuno settlement to be the basic template for the Shinanogawa settlement that is expected by year’s end. Kang Jian and the Lawyers Group were not involved in the Nishimatsu Yasuno lawsuit or subsequent negotiations, and the Shinanogawa plaintiffs view that model as unacceptable.

Arimitsu Ken, in his commentary below, frames the Nishimatsu Yasuno approach more positively as a belated first step toward comprehensive settlement of the Chinese forced labor redress claim, and urges the Japanese government to break with its long pattern of inaction by accepting responsibility and providing fitting compensation. As executive director of the Tokyo-based Network for Redress of World War II Victims, Arimitsu interacts with reparations advocates in and out of Japan at both grassroots and legislative levels. His network aims to comprehensively address unresolved war legacies ranging from Japan’s system of military sexual slavery to the postwar internment of Japanese soldiers in Siberia. A second article by Arimitsu, reprinted from the Asahi Shimbun, makes the related case that Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio’s vision of an East Asian community will remain a pipedream unless his administration squarely faces Japan’s past.

However it is evaluated, the Nishimatsu settlement has important implications for the 20 or so other still-operating Japanese firms that likewise badly mistreated Chinese workers in Japan, profited from their uncompensated forced labor, and now enjoy legal immunity as a result of the Japan Supreme Court ruling. Following the 2007 ruling, even Mitsubishi Materials Corp., which earlier in the decade aggressively defended itself using revisionist historical arguments, has expressed willingness to settle claims stemming from Chinese forced labor—but only on the condition that the Japanese state participates in the process.

Wartime images of construction site for Yasuno hydroelectric plant

The Nishimatsu Settlement: Implications for Korean Forced Labor and Allied POWs

Nishimatsu’s shift from confrontation to conciliation also has meaning for backers of redress for forced labor by Koreans and Allied POWs, whose movements continue to make slow but significant progress. Hundreds of thousands of Koreans were conscripted into working in Japan for private companies that typically withheld the bulk of their wages; in the late 1940s the funds were quietly deposited in the Bank of Japan and remain there today. Having waived all rights to the money under its 1965 treaty with Japan, the South Korean government now needs details about the BOJ deposits in order to provide former conscripts with the state compensation it authorized in 2007.

In spring 2009 the Korean Broadcasting System aired a 50-minute documentary called “The Secret of the 200,000,000 Yen Financial Deposits” and charged Japan with perpetrating a “60-year cover up.” Pressure on Japan to come clean about the conscription-linked cash may grow next year as the two nations observe the one-hundredth anniversary of Korea’s annexation by Japan in 1910. Meanwhile, the remains of hundreds of military and civilian conscripts are being returned to South Korea from Japan at a glacial pace. Giving preferential treatment to cases of military conscription, the Japanese government has invited Korean family members to memorial services in Tokyo and made small condolence payments on a “humanitarian” basis. Corporate Japan is not cooperating with the location, identification and return of civilian remains.

Allied POW reparations efforts got a big boost last January when, following nearly two years of evasion and denial, then-Prime Minister Aso Taro was finally forced to admit that there were POWs at Aso Mining in 1945. An Australian survivor of forced labor at Aso Mining and the British son of an Aso POW who died after the war visited Japan in June 2009, attracting heavy media coverage and meeting with a sympathetic Hatoyama. Although Prime Minister Aso refused to meet the visitors or apologize to them, his administration was pressured into issuing official apologies in the Diet to “all POWs” in February and March.

In May 2009 the Japanese ambassador to the United States apologized in Texas at the final convention of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, then waded into the audience to shake hands with wheelchair-bound survivors of the Bataan Death March. But when the head of the American POW group asked the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) for a similar gesture, citing the group’s charter on ethics and corporate social responsibility, his letter went unanswered.

Japan has announced that a new reconciliation program for American former POWs and their kin will begin in 2010. More than 1,000 British, Dutch and Australian ex-POWs and family members have been invited to Japan since 1995 through the Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative, while related programs have benefitted Canadians and New Zealanders. Yet these laudable initiatives and sustained attention to Allied POWs raise the bar for reconciliation with Asian forced laborers, especially since Tokyo’s relations with the West are already much smoother than those with China or Korea. Little is ever mentioned, or even known, about the millions of Asians pressed into harsh service for the Japanese empire outside of the home islands.

Chinese Forced Labor, Japanese Government Duplicity, and the Future of China-Japan Relations

The case of Chinese forced to work in Japan, the focus of this package of articles, best illustrates the extreme brutality of Japan’s wartime mobilization of labor and the basic dishonesty of the nation’s postwar approach to dealing with the aftermath.

Nishimatsu plaintiffs during visit to Yasuno worksite last month

Expecting widespread war crimes prosecutions by the Allied coalition that included the Nationalist Chinese government, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) in 1946 secretly compiled the so-called Foreign Ministry Report (FMR) with the active cooperation of all 35 companies involved, essentially as a tool for government and corporate self-defense. The 646-page FMR, while attempting to portray the labor program in the best possible light, details how beginning in 1943 a total of 38,935 Chinese men between the ages of 11 and 78 were brought to Japan to toil at mines, construction sites and docks from Kyushu to Hokkaido. The FMR states that 6,830 workers died, making for a death rate of 17.5 percent (more than one in six), but at some sites half of the workforce perished.

Due to Cold War priorities only two war crimes trials involving Chinese forced labor were held, prompting the Japanese government to suppress or destroy the Foreign Ministry Report and related records. Progressive Japanese citizens pushed the state to repatriate the remains of deceased victims to China throughout the 1950s and early 1960s—and to admit the inhumane reality of the forced labor program. Records declassified by MOFA in 2002 depict how the state consistently evaded responsibility by deceiving the Diet and citizen groups about its postwar production and possession of Chinese forced labor records.

This cover up peaked during the late-1950s administration of Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, who had been the wartime cabinet member formally in charge of Japan’s labor schemes and was later imprisoned for three years as a Class A war crimes suspect. Kishi as prime minister claimed the Chinese had voluntarily come to Japan and worked willingly; other postwar officials described the nature of the labor program as unknowable due to the lack of documentation.

That stance became untenable in 1993 when a Chinese civic group in Japan supplied the NHK broadcasting network with a dusty but complete copy of the Foreign Ministry Report, along with a mountain of records upon which the report was based. The documents describe worker recruitment in North China by means of deception and “laborer hunting,” which typically meant the abduction of farmers from their fields. The FMR also contains breakdowns of the large sums of money that companies received from the central government after the war as reimbursement for losses supposedly incurred while administering the program, even though workers were never paid wages. The Japanese government today concedes that the Chinese labor program was carried out in a “half-forcible” manner, using the same term it originally employed in the FMR.

Capping this pattern of insincerity, MOFA announced in 2003 that it had searched its own basement storeroom and discovered 20,000 pages of the worksite reports submitted in 1946 by the corporate users of Chinese forced labor. Prodded into checking its own in-house archives late last year, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare similarly unearthed various records confirming there were Allied POWs at Aso Mining, though the ministry cited privacy concerns in refusing to make the records public. It is hoped that Japan’s new government will reform the dysfunctional national archive system and declassify the wartime and postwar documents needed to clarify the historical record and enable redress work to proceed.

The Nishimatsu Model and the Road Ahead

Can Nishimatsu’s done deal with Chinese from the Yasuno worksite, along with the company’s pending pact with Chinese from the Shinanogawa worksite, serve as a wedge for producing greater post-LDP responsibility concerning Chinese forced labor, other classes of forced labor and perhaps the longer list of Japan’s wartime transgressions?

That seems unlikely, at least in the near term, for Japan shows few signs of following the German example. Set up in 2000 and funded in equal measure by the German federal government and corporate sector, the Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and the Future” paid out some $6 billion in compensation to 1.7 million Nazi-era forced laborers or their heirs, mostly non-Jews living in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. The foundation provided robust individual apologies and continues to emphasize truth telling through educational activities. However, Germany confronted the forced labor legacy only when faced with the public relations nightmare of class-action lawsuits in the United States, and only after the U.S. government helped broker a complex deal that granted the German state and companies legal immunity.

The Chinese forced labor claim, though, has been hamstrung by weak support from the Chinese government and generally low international awareness. Beijing authorities were slow to allow victims to file compensation lawsuits in Japan and have tended to view redress activists with suspicion. State media reported in the middle of this decade that similar lawsuits against Japanese firms would be allowed in the Chinese court system. The reports even named the first prospective plaintiff and defendant (Mitsu Co.), but such suits never materialized. Yet forced labor redress supporters occasionally have been permitted to directly present their demands at the Chinese offices of Japanese companies, and last year they held their largest-ever meeting in Shandong.

The Nishimatsu model clearly represents important forward motion for the compelling and comparatively resolvable Chinese forced labor issue. If the few hundred survivors of the injustice are to obtain reparations in their lifetimes, the company’s move is likely the “last best hope for a start.” To the extent that Japan’s political and economic leaders are moved to recalculate the costs of perpetual intransigence and the potential benefits of improved relations with Asian neighbors, the Nishimatsu settlement may contribute to eventual improvement in the nation’s mostly dismal record of atoning for its war misconduct.

*************************

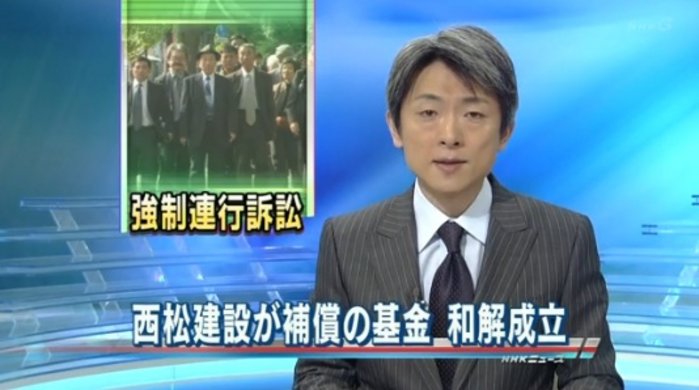

Japanese TV coverage of Nishimatsu settlement (video available)

Nishimatsu Settlement is Devoid of Facts and Accountability

KANG JIAN

On October 23, 2009, Nishimatsu Construction Co. secured a “Settlement” with eight wartime Chinese laborers who were captured and enslaved at the Nishimatsu Yasuno worksite and their survivors. Under the “Settlement Terms” signed by both parties, Nishimatsu Co. will not assume legal liability, but agrees to pay 250 million yen as “compensation” to the 360 Chinese laborers forced to work at the Yasuno site located in Hiroshima, Japan.

The plaintiffs in the separate case involving Chinese forced laborers at the Nishimatsu Shinanogawa worksite in Niigata are represented jointly by myself and lawyers in Japan including Onodera Toshitaka, Matsuoka Hajime, Takahashi Toru and Morita Taizo. The Shinanogawa plaintiffs have clearly expressed that the terms of the Yasuno “Settlement” are unacceptable.

I. Background of the Nishimatsu Co. lawsuits

In the first half of the twentieth century, Japan’s militaristic government invaded China, bringing terrible disaster to Chinese people. As part of its national strategy to maintain a long-term war of invasion, the Japanese government abducted at least some 40,000 Chinese laborers beginning in 1943. They were sent to Japan to perform hard labor at 135 sites belonging to 35 Japanese corporations, including Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Kajima. Forced to work long hours under horrendous conditions, in just a year or so 6,830 Chinese laborers died, many of them succumbing to diseases, while others were disabled permanently.

When the invasion of China ended, the Japanese government and those Japanese corporations gave neither wages nor compensation to the forced Chinese laborers. Instead, they hurriedly sent the Chinese laborers away.

Since 1995, with the support of a number of conscientious Japanese citizens and lawyers, as well as support from people and lawyers in China, some surviving Chinese victims have launched lawsuits in Japan requesting compensation from the Japanese government and corporations. After 10-odd years of litigation, court decisions in Japan confirmed that the Japanese government and those corporations illegally abducted and enslaved the Chinese laborers. It was confirmed that the Chinese laborers performed hard work under horrendous conditions, enduring great harm and suffering both mentally and physically.

On April 27, 2007, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan made a final judgment on the first case of Chinese laborers’ claim for damages against Nishimatsu Co. It dismissed the legitimate claims by the Chinese laborers on the ground that their right to claim had already been waived in the China-Japan Joint Communique signed in 1972. However, the judgment acknowledged the abduction of Chinese laborers and the verdict stated:

“The victims of the case endured great pain both mentally and physically. The appellant (Nishimatsu Construction) forced the Chinese laborers to work in the aforesaid working conditions, benefiting from doing so and also obtaining government indemnification payments. In light of these facts, we expect related parties including the appellant to make efforts to provide charitable relief for the losses suffered by victims in this case.”

Such a statement in the Supreme Court verdict is obviously addressed to the Japanese government and those corporations that enslaved the Chinese laborers. After the ruling, Nishimatsu Co. began negotiating with the Chinese victims in response to prodding from various parties.

Nishimatsu Co. enslaved Chinese laborers at two locations, namely the “Shinanogawa worksite” with 183 Chinese laborers (at Shinanogawa, Niigata Prefecture) and the “Yasuno worksite” with 360 laborers (at the Yasuno Power Plant in Hiroshima). From the beginning of the negotiations, Nishimatsu Co. insisted on modeling the agreement on the Hanaoka “settlement” nine years ago. The Hanaoka agreement is characterized by:

1. The representation of facts in an abstract manner without admitting legal liability. Liability for damages caused by extreme violation of human rights is whitewashed into a moral obligation to provide charitable relief.

2. Payment of a small symbolic “settlement” amount to the victims. Such a small amount must also cover expenses such as memorial ceremonies, exchange activities, investigations, etc.

During negotiations with Nishimatsu Co., the corporation did not deal with the Chinese laborers at both worksites as a whole. Instead, the talks were conducted separately.

The case of Chinese laborers enslaved at the Yasuno worksite was represented exclusively by lawyers and a support group in Japan, with no participation from Chinese lawyers. While we should trust the integrity and sincerity of these Japanese lawyers and supporters in helping the Chinese victims, can we expect the victims to fully and accurately understand the terms of the “Settlement” and their implications, given the fact they were represented by lawyers who were foreigners to them? I have some reservations about this. If Nishimatsu Co. intended to fully resolve all outstanding claims of Chinese forced laborers, why did it conduct the negotiations with victims of the two worksites separately? From the very beginning, we requested a single negotiation process for the Chinese laborers at both sites, but Nishimatsu Co. ignored our request.

Attorney Kang Jian (left) outside Japanese courthouse after legal defeat

On September 18, 2009, representative plaintiffs from the Shinanogawa worksite and their survivors wrote to the president and each director of Nishimatsu Co. They made it clear that a settlement should be made with sincerity. Nishimatsu Co. should admit the historical facts and apologize explicitly to the Chinese victims and their survivors. It should provide “compensation” to the slave labor victims and their survivors (not in the form of charitable relief or settlement money). It should adopt an integrated and unified approach to resolving all the claims with sincerity, without resorting to a divide and conquer tactic. Nishimatsu Co. has not replied. Instead, the company continued to adopt the divisive approach and finally signed the problematic “Settlement Terms” with eight Chinese claimants from the Nishimatsu Yasuno worksite last October 23.

II. A “settlement” lacking in accountability

Article 1 of the “Settlement Terms” still denies the legal liability of Nishimatsu Co., citing a wrong judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan made on April 27, 2007 (hereafter the “4.27 ruling”). The liability for damages caused by severe violation of human rights is converted into humanitarian relief. This is consistent with the problematic principles of the Hanaoka “settlement”. In the 4.27 ruling, the Supreme Court unilaterally misinterpreted Article 5 of the 1972 China-Japan Joint Communique, concluding that the Chinese government had given up the right to claim damages, including the right of its citizens to claim damages.

On the day of the 4.27 ruling, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated clearly that the Japan Supreme Court had unilaterally interpreted the China-Japan Joint Communique in an illegal and invalid manner.

III. A “settlement” ignoring facts of history

Article 2 of the “Settlement Terms” simply regards the abduction of Chinese laborers as a decision of the wartime Japanese cabinet. In fact, the Japanese corporations enslaving the Chinese at that time were all military suppliers. They had common interests with the state. Many courts in Japan dealing with the Chinese laborers’ claims for compensation have ruled that the Japanese government and corporations jointly planned and carried out the abduction and enslavement of the Chinese laborers. These judgments based on historical evidence submitted were issued by the Tokyo High Court, Fukuoka District Court, Fukuoka High Court, Niigata District Court, Sapporo District Court, Sapporo High Court, Miyazaki District Court, Gunma District Court, Kyoto District Court, Nagano District Court, Yamagata District Court, Hiroshima High Court and the Japan Supreme Court.

One example of such rulings relates directly to the lawsuit by Chinese laborers at the Nishimatsu Yasuno worksite. On April 27, 2007, the Japan Supreme Court found that

“(W)ith the Lugouqiao Incident (Marco Polo Bridge Incident) in July of Showa 12 [1937], Japan and China went to war (hereafter called the “Sino-Japanese War”). With the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 8, Showa 16 [1941], the Pacific War broke out. In the course of these wars, the military supplies corporations experienced a labor shortage, especially in labor-intensive units such as mining, construction and loading at maritime docks. In view of the manpower shortage, the Japanese government created a labor mobilization scheme under the National General Mobilization Law announced in April of Showa 13 [1938]. At the same time, it brought in many laborers from the Korea Peninsula, which had been annexed by Japan. However, the serious shortage of manpower in labor-intensive units remained acute.

The coal, construction and other industries, foreseeing a labor shortage early in the war, began considering importing foreign workers, particularly workers from northern China. Their wish was presented to the Japanese government. As a result, on November 27, Showa 17 [1942], the cabinet passed a resolution about importing laborers from China.

The appellant (Nishimatsu Co.) was a civil construction corporation that had been given many railway and road construction projects because it supported military operations of the Japanese troops in China. The corporation had undertaken the project of building the Yasuno Power Plant in Yamagata-gun, Hiroshima, during the period from June of Showa 18 to March of Showa 22 [1943-47]. However, there was no guarantee of sufficient manpower. Therefore, the corporation considered using Chinese workers to supplement its workforce. In April of Showa 19 [1944], it submitted an application to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, which was responsible for allocating and managing imported labor. It asked for the importation of Chinese laborers who would be deployed in power plant construction …

The above-mentioned 360 Chinese laborers were loaded onto a cargo ship in Qingdao on July 29, Showa 19 [1944]. The laborers arrived at the Port of Shimonoseki seven days later, during which time three of them died of sickness. They were then transported to the site of the Yasuno Power Plant, and were divided into four groups when being housed. They were placed under constant police surveillance. The laborers were divided into two shifts, working round the clock. They performed work such as excavating tunnels. The three meals a day were small in quantity and poor in quality, and they often went hungry. All of them began to lose weight. Furthermore, clothing and shoes were poorly provisioned and sanitation was very poor. No treatment was offered to the wounded and sick … .”

Another example of such rulings is related to the Chinese laborers at the Nishimatsu Shinanogawa worksite. On June 16, 2006, the Tokyo High Court gave a second-instance ruling on the Chinese laborers’ claim against the Japanese government and corporations including Mitsubishi and Nishimatsu. It confirmed that the state (i.e., the Japanese government) and private enterprises had jointly committed an illegal act. The court found that Japanese soldiers and Nishimatsu employees

“abducted the first-instance plaintiffs who had been living a life of serenity, taking them to a foreign country and enslaving them in extremely dreadful conditions. Such conduct was inhuman and should be vehemently condemned … The workers slept closely packed together in a head-to-head configuration in a wide and long makeshift structure built with boards. The structure was surrounded by walls. There were also electrified fences … As regards clothing, food and housing, the Chinese laborers were ill-treated. As they had to perform hard labor every day, many broke down … .”

As the verdicts from many Japanese courts show, a cabinet resolution by the Japanese government was absolutely inadequate to explain away the illegal acts of abducting and enslaving the Chinese laborers. The Japanese government and related Japanese corporations jointly engaged in the abduction and enslavement of the Chinese laborers in pursuit of their common illegal interests. In this Yasuno “Settlement”, Nishimatsu Co. ignored the fact that they had subjected the Chinese laborers to cruel and ruthless treatment. This refusal to face the facts casts serious doubt on the company’s sincerity.

IV. Cheap “compensation” hardly indicates remorse or sincere reconciliation

Article 4 of the “Settlement Terms” states that Nishimatsu Co. will pay a “settlement” of 250 million yen as “compensation” for the 360 Chinese laborers at the Yasuno worksite. This means that each laborer will get about 690,000 yen, amounting to approximately RMB 50,000 [or $6,900 at 100 yen per dollar]. But it must be pointed out that this amount must also cover expenses incurred in building a memorial in Japan, holding memorial ceremonies, conducting investigations, etc.

These terms are the same as in the Hanaoka “Settlement”. Under the Hanaoka agreement, fully half of the “settlement” amount given to the Chinese laborers was first deducted (i.e., 250 million yen was deducted from 500 million yen) for the expenditures on exchange visits, investigations, memorial ceremonies, etc. Only then was the remaining half given to the 986 Chinese labor victims. Each Hanaoka victim was to receive a little more than RMB 10,000.

If the objective of the Yasuno “Settlement” is to compensate the Chinese laborers, then the costs for erecting a memorial, victims’ visits to the worksite, memorial ceremonies and investigations should not have been included as part of the “settlement” amount. These expense items are not compensatory in nature. Lumping money for items of different natures hardly supports the claimed intention of compensation with the “settlement” amount.

In order to deal with the trial of Japanese war criminals by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the postwar Japanese government produced the Investigative Report on Working Conditions of Chinese Laborers (hereinafter called the “Foreign Ministry Report”). Book III of the Foreign Ministry Report contains a section recording that the 35 Japanese corporations involved in enslaving the Chinese laborers told the Japanese government that the use of Chinese laborers had incurred losses for them in the form of administrative costs, food costs, wages, etc. However, the Chinese laborers did not receive any wages. The corporations did not mention the gains generated from the Chinese laborers who performed hard work for them without pay.

The Japanese government understood full well that the so-called “losses” claimed by the corporations were non-existent. However, it still paid indemnification payments of 56,725,474 yen in total to the corporations concerned, of which Nishimatsu Co. got 757,151 yen. (Note that in its 4.27 ruling, the Supreme Court of Japan confirmed that Nishimatsu Co. actually received indemnification payments of more than 920,000 yen.) We do not rule out the possibility that the Japanese government took this action to evade state compensation liability by transferring treasury funds to the Japanese military supplies corporations.

According to calculations by Japanese lawyers, the yen value in 1946 is equivalent to 1,000 times the current yen value. This means that those Japanese corporations received government indemnification payments for using Chinese workers that would be worth more than 56.7 billion yen today [$567 million]. Nishimatsu Co.’s government indemnification payment would be worth 750 million yen today [$7.5 million]. If calculated based on the verified facts of the 4.27 ruling, Nishimatsu Co.’s government indemnification payment would be equivalent to more than 920 million yen at today’s value [$9.2 million]. Thus, the 250 million yen offered to the Chinese laborers in the Yasuno “Settlement” is far from enough to cover their wages and would hardly qualify as compensation.

In this serious case of human rights violation, the perpetrating parties do not face up to the facts of history and do not assume liability. A small amount of money is given to victims to brush them off. Such actions indicate a lack of remorse and sincerity in reconciliation.

V. “Friendship Foundation” – the laurel conceals a denial of responsibility

Article 6 and Article 7 of the “Settlement Terms” state that the foundation set up to manage the “settlement” is named the “Nishimatsu Yasuno Friendship Foundation”. The foundation is subordinate to the Japan Civil Liberties Union, a civic organization in Japan. How can a “compensation” fund for Chinese victims be controlled and managed by a Japanese civic organization?

Maintaining friendly exchanges and building friendly relationships are the wishes of every good and honest person. In the Yasuno case, the “Settlement Terms” fail to indicate the fact that Nishimatsu Co. severely violated the human rights of the Chinese laborers and should assume liability. There is no basis to the so-called “friendship” that is being put on display. For the Chinese labor victims, seeing this usage of the term “friendship” is obviously like being forced to swallow a bitter pill. A friendly gesture without foundation cannot be regarded as friendship. Professor Liu Jiangyong at Tsinghua University told a reporter for The Beijing Youth Daily that we should “avoid creating a situation where [the Japanese] would rather pay money than face up to their historical responsibilities; otherwise, there will be bad consequences for the reconciliation between the two peoples.”

Forced labor survivors and families at Kang’s Beijing office in 2000

In contrast to the Nishimatsu Yasuno Friendship Foundation, the Remembrance, Responsibility and Future Foundation was established in Germany in 2000 to compensate the laborers enslaved in wartime. It squarely faced history and explicitly assumed responsibility, comforting the hearts of victims. This is the only way to face the future moving forward.

VI. “Settlement Terms” and “Confirmation of Settlement Issues”

The lawsuit regarding Chinese laborers at the Nishimatsu Yasuno worksite came to an end on April 27, 2007. The related lawsuit regarding Chinese laborers at the Nishimatsu Shinanogawa worksite also ended that year. The Yasuno “Settlement” is an agreement secured through out-of-court negotiation. Nishimatsu Co. requested that the “Settlement Terms” signed by both parties be submitted to the Tokyo Summary Court for affirmation by a judge so that execution would be guaranteed. Consequently, the “Settlement Terms” concluded by both parties were affirmed by a Japanese judge on October 23, 2009.

Article 8 of the “Settlement Terms” states that the Yasuno “Settlement” is regarded as having completely resolved the compensation issue for the 360 laborers at the Yasuno worksite, and the laborers concerned and their survivors have given up the right to claim against Nishimatsu Co. in other countries and regions. Such stipulation is consistent with the problematic Hanaoka “settlement”.

In fact, the Japanese lawyers representing Nishimatsu Co. and the Chinese laborers prepared another document titled “Confirmation of Settlement Issues”, which was not submitted to the Tokyo Summary Court. In that confirmation document, the lawyers of both parties interpreted Article 8 as “without prejudicing the legal rights” of individuals who disagree with the Settlement. If both parties could reach such a consensus, why couldn’t this explanation be added directly to the more formal “Settlement Terms” that were affirmed by a court judge? This would have given the “confirmation” document more legal weight than by treating it as an out-of-court interpretation.

VII. The “settlement” negotiations are still a positive step in the right direction

The “Settlement Terms” described in this paper are problematic with regard to fundamental principles. However, considering the fact that the Japanese government has refused to assume liability and that other Japanese corporations complicit in the enslavement of the Chinese laborers have refused to negotiate, Nishimatsu Co.’s effort to negotiate with the Chinese laborers should still be viewed positively.

Nishimatsu Co. does offer an “apology” in the “Settlement Terms”. But this is not accompanied by any specific, relevant facts, producing a vague impression likely to confuse the general public as to what the apology is all about. However, it is still a step forward for Nishimatsu Co. to offer a written “apology”.

War brings disaster and pain to people. We will not see a repeat of such tragedy only if we learn our lesson. Learning from history is what both the perpetrators who initiate a war and victims of wartime atrocities should take to heart. As human civilization continues to progress, the world expects the Japanese government and corporations concerned to resolve the problems left in the wake of that evil war which trampled severely upon the human rights of Asian people.

*************************

The Nishimatsu Settlement is a Positive Step, Japanese Government Action Now Needed

ARIMITSU KEN

It was announced on October 23, 2009, that an agreement for an immediate settlement was reached at the Tokyo Summary Court between surviving victims and bereaved families of Chinese laborers, who were forced into wartime work at the construction site of the Yasuno power plant in Hiroshima Prefecture, and Nishimatsu Construction Co.

I commend Nishimatsu Construction Co. for finally accepting the Japan Supreme Court’s recommendation two and a half years after it was issued on April 27, 2007, and the plaintiffs for accepting this settlement.

I salute the plaintiffs and other victims, bereaved families and other families, supporters and the team of lawyers who have fought a long and difficult battle for the 16 years since they presented three demands in August 1993, and for the 11 years since they filed suit in January 1998. That the lead plaintiff, the leader of the support organization, and the lead lawyer all have passed away is yet another reminder of the slowness of the response by the defendant company and the Japanese courts.

This is the third time settlement between Chinese forced labor plaintiffs and a Japanese defendant company. It follows the November 2000 settlement with Kajima in the case involving the Hanaoka Incident, and the April 2004 settlement with Nihon Yakin in the Oeyama nickel mine case. [The latter agreement provided per capita payments of about $35,000 to a mere six plaintiffs.] This Nishimatsu Yasuno settlement is significant, however, in that it proved that plaintiffs could continue their fight and achieve their goal even after the Supreme Court dismissed their case, demonstrating that sustained efforts by all parties to negotiations could produce a settlement.

Provisions of the settlement include those key words that the victim side has long sought, such as “acknowledgment of historical responsibility,” “apology,” “building of a memorial,” and “compensation for the suffering.” Today’s press conference was attended by representatives of both the plaintiffs and Nishimatsu Construction Co. While the 2000 Hanaoka settlement left some issues inadequately addressed and created problems later, I believe that this settlement overcame those issues and became a better settlement. It is noteworthy that, as a new framework for payment, an independent non-profit organization, the Japan Civil Liberties Union (JCLU), was chosen as the trustee of the trust fund.

Scenes from memorial service and redress rally in Tokyo, summer 2009

I hear complaints from the plaintiff/victim side about the amount of the compensation and think their complaints are legitimate. It is extremely irresponsible and insincere for the Japanese government, which has greater historical and political responsibilities than do companies, to have taken no action. Obviously not only companies but also the Japanese government should apologize and pay compensation because the “Foreign Ministry Report” showed that forcibly taking Chinese people to Japan and making them perform forced labor was done according to the official decision of the Tojo Cabinet in November 1942, and that 38,935 Chinese people were sent to and used by 35 companies at 135 worksites.

I would like to call on the new Japanese government, which came into power after the recent election, to take immediate and sincere action. Next year will mark the sixty-fifth anniversary of the end of WWII, yet it is regrettable that only three companies have accepted a settlement in the past several years. Some companies have told the courts that they would “follow the lead of the government if it decided to take action.”

Although this situation is a negative legacy from successive LDP administrations, I strongly urge that the new administration, which promised to strengthen Japan’s Asian diplomacy, immediately start work on this issue. It is the responsibility of Japanese citizens to realize that time is running out and to make every effort to prompt their government to move forward.

Resolving Postwar Redress Is Crucial for Japan’s Asia-centric Policy

ARIMITSU KEN

With Prime Minister Hatoyama’s visits to South Korea and China, Japan’s Asia–centric “Fraternal Diplomacy” has begun. A strategic approach is needed for countries in the region to prosper together and to construct a peaceful and stable “East Asian Community.”

What is crucial for that policy is the unresolved matter of postwar redress. This encompasses a wide range of issues involving Japan and other countries, such as the forcible taking of Korean and Chinese people to Japan as forced laborers, Allied POWs’ forced labor, Siberian internment, the fire bombing of civilians, and recovering war remains.

We cannot ignore the fact that many victims are still suffering after 64 years from injustices and visible and invisible scars caused by the war.

Representing various citizen groups, I have been involved in efforts to resolve issues of postwar redress for the past 20 years. More than 70 lawsuits seeking redress have been filed with Japanese courts since the 1990s. A handful of settlements have been reached with a few companies involved in forced labor, but all these lawsuits ended with legal claims being rejected. Yet in some rulings judges have acknowledged the illegality of the defendants’ conduct, showed sympathy for the victims, and recommended a legislative resolution.

The 1993 Kono statement on the issue of “comfort women” did acknowledge the involvement of military authorities and the system’s forcible nature. But interviews with actual victims, upon which the statement was based, were conducted with only 16 former “comfort women” during a five-day period by government officials who visited South Korea. No victims from China, Taiwan, the Philippines, or Indonesia were interviewed. Successive prime ministers have referred to the 1995 Murayama statement that mentioned “remorse and apology.” What victims want, however, is to have the Japanese public know how they suffered and remember it.

Western media reported that 300 Allied POWs were forced to work during the war at the coalmine belonging to Aso Mining, run by the father of former Prime Minister Aso. Yet Mr. Aso continued denying this until the end of last year by saying, “It has not been confirmed.” When the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare revealed the existence of records proving the historical reality, the then-prime minister retracted his previous statement early this year—without ever directly apologizing.

During the long years of LDP rule, the issue of unfinished postwar redress could not be resolved. On the contrary, old wounds stemming from the war were often reopened and trust was betrayed. With jurisdiction over these issues being divided among the ministries of Foreign Affairs, Health, Labor and Welfare, Internal and Communication Affairs, Justice, and the Cabinet Office, victims were merely given the “runaround.” Their disappointment with and negative feeling towards Japan deepened. A policy to change that disappointment into trust should be adopted before creating an “East Asian Community.”

Prime Minister Hatoyama has met with war victims on many occasions and shared the bitter feelings held by victims and bereaved families. Now that we have a new DPJ administration, there is a need to show repentance and determination in a tangible way. Several bills relating to postwar redress have been introduced in parliament by the DPJ and other parties. I hope lawmakers will work on them earnestly to achieve the goal. Clarifying Japan’s national responsibility and securing the necessary redress funding will be a sure step towards an age of trust and peace-building.

Kang Jian is an attorney with the Beijing Fang Yuan Law Office and a member of the All China Lawyers Association’s Committee for Redress Claims against Japan. The original Chinese version of her article, which she prepared for The Asia-Pacific Journal, is available here. Kang’s article was translated by Thekla Lit, co-chair of Canada Association for Learning & Preserving the History of WWII in Asia.

Arimitsu Ken is executive director of two Tokyo-based groups: Network for Redress of WWII Victims, and the Association of Lawyers and Citizens Seeking Legislative Solutions for Postwar Redress. His first article was prepared for The Asia-Pacific Journal and is available in Japanese here. The second article appeared in the Asahi Shimbun on October 28, 2009, and is available in Japanese here. Both of Arimitsu’s articles were translated by Kinue Tokudome, executive director of US-Japan Dialogue on POWs.

William Underwood, a Japan Focus coordinator, is an independent researcher of reparations for forced labor in wartime Japan. He can be reached at [email protected].

Recommended citation: Kang Jian, Arimitsu Ken and William Underwood, “Assessing the Nishimatsu Corporate Approach to Redressing Chinese Forced Labor in Wartime Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 47-1-09, November 23, 2009.

Related Articles

Kang Jian and William Underwood, Japan’s Top Court Poised to Kill Lawsuits by Chinese War Victims

Fukubayashi Toru, Aso Mining’s Indelible Past: Verifying Japan’s Use of Allied POWs Through Historical Records

Fujita Yukihisa, Aso Mining’s Indelible Past: Prime Minister Aso Should Seek Reconciliation With Former POWs

Michael Bazyler, Japan Should Follow the International Trend and Face Its History of World War II Forced Labor

Lawrence Repeta, Aso Revelations on Wartime POW Labor Highlight the Need for a Real National Archive in Japan

Kinue Tokudome, The Bataan Death March and the 66-Year Struggle for Justice

William Underwood, Chinese Forced Labor, the Japanese Government and the Prospects for Redress

William Underwood, Mitsubishi, Historical Revisionism and Japanese Corporate Resistance to Chinese Forced Labor Redress

William Underwood, NHK’s Finest Hour: Japan’s Official Record of Chinese Forced Labor

* The 59-minute documentary nationally televised by NHK on August 14, 1993, was called “The Phantom Foreign Ministry Report: The Record of Chinese Forced Labor (Maboroshi no Gaimusho Hokokusho: Chugokujin Kyosei Renko Kyosei Rodo no Kiroku).” It can be viewed on YouTube in five parts: Part 1 … Part 2 … Part 3 … Part 4 … Part 5

Additional Japanese TV coverage of Nishimatsu settlement

(video available)