Korean Overseas Information Service and William Underwood

Introduction:

In August 2005, marking the sixtieth anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonialism, the South Korean government stated that Japan continues to bear legal responsibility for “inhumane illegal acts” committed against the country and its nationals before and during the Asia Pacific War. Individual claims involving comfort women, victims of the atomic bombings and forced laborers abandoned on Sakhalin Island were said to remain unresolved by the 1965 treaty that normalized relations between Seoul and Tokyo.

In recent years the Japanese government, quietly and on “humanitarian grounds,” has helped fund the repatriation to South Korea of some Sakhalin Koreans, more than 40,000 of whom endured a harsh Cold War existence as “stateless persons” on the island controlled by the former Soviet Union. As many as 150,000 Koreans were brought to Sakhalin between 1910 and 1945, many of them to work in Japanese coal mines and lumber yards. The latest repatriation efforts are described by the Korean Overseas Information Service in the article below. (Background information on the difficult history of Sakhalin’s Koreans can be found at Wikipedia.)

The Japanese government is currently taking other modest steps to partially address the forcible conscription of hundreds of thousands of Koreans for military and civilian work throughout its wartime empire—while insisting that the 1965 bilateral accord represents a final legal settlement. Within Japan, Japanese and South Korean officials are jointly inspecting charnel houses holding the remains of civilian labor conscripts and, as is now being clarified, their offspring. Tokyo is also helping to pay for South Korean family members to visit overseas battlefields where their conscripted relatives were killed.

Hundreds of sets of Korean remains (mainly military conscripts) long housed at Tokyo’s Yutenji temple are slated to be returned to South Korea before the end of the year. It has recently come to light that Japanese authorities attempted to repatriate the Yutenji remains to both South Korea and North Korea in the 1970s. But Seoul’s anti-communist regime blocked the plan because it might have led to warmer North Korea-Japan relations, underscoring how states place low priority on repairing war-related injustices even when their own nationals are the victims.

South Korea’s current government (its most human rights-minded ever) last month backed away from its own proposed legislation, actually approved by the National Assembly, that would have used domestic funds to compensate Koreans conscripted by Imperial Japan. The Roh administration became concerned about the measure’s rising price tag and the fairness of excluding Korean War victims. A revised compensation bill will be introduced this fall.

On Sept. 5-6 in Mongolia, meanwhile, top diplomats from Japan and North Korea resumed long-delayed talks on normalizing relations. Japan is aiming to establish Tokyo-Pyongyang ties using the same formula employed with Seoul in 1965: providing economic assistance while sidestepping legal responsibility for historical wrongdoing. North Korea is placing top priority on obtaining reparations for Japan’s colonization of the Korean peninsula, a legacy that involves the ongoing plight of ethnic Koreans in Sakhalin. The negotiations ended without positive result. –WU

More than 600 elderly ethnic Koreans who have been residing on an island in the Russian Far East since World War II will permanently return home this fall, Korea’s Red Cross said Wednesday (Aug. 22).

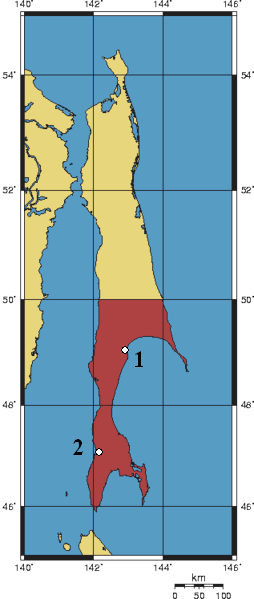

Japan forced about 150,000 Koreans to work on Sakhalin Island in coal mines, pulp mills and other military facilities during World War II. At the time, the southern half of Sakhalin was under the control of the Japanese empire; Japan had annexed the Korean Peninsula as a colony in 1910.

When the war ended in Japanese defeat, Russia regained control of the entire island and the Korean Peninsula was liberated, but about 43,000 Koreans remained stranded on Sakhalin after being classified as “stateless people.” The situation forced many to obtain Russian citizenship, and live from hand-to-mouth as coal miners or farmers.

“A total of 610 aged people will return home for permanent residence from September through November as part of a 15-year-old government program aimed to aid Sakhalin Koreans,” said Kim Dae-young, a Red Cross official in charge of the aid program for overseas Koreans.

It will be the second-largest group ever to return home since 1992, when Korea launched the program jointly with Japan to help elderly Sakhalin Koreans who were eager to permanently settle in Korea. In 2000, a group of 900 ethnic Koreans entered Korea for resettlement in Ansan, about 42 kilometers south of Seoul. So far, 1,684 people have returned home under the program.

“The Seoul government aims to repatriate all first-generation Koreans by 2009,” Kim said.

The 610 returnees will be provided with 300 leased apartments in the western port city of Incheon, he added.

Incheon is one of several residential areas currently available for the Sakhalin Koreans, along with those in Seoul and Ansan. The returnees are entitled to a monthly government allowance of about 400,000 won ($425) per person if they have no income.

Japan initially supported the cost of building a village for Sakhalin Koreans on land in Ansan, which was provided by the Seoul government and the local government. As the village has already reached its full capacity of about 900 people, those who returned after 2000 have been separately allowed to live in leased apartments in Ansan, Incheon and Seoul.

Japan later turned its method of support to providing airfare and basic household goods, according to Kim.

Many Koreans believe Japan should contribute more, since it brought back most of its 380,000 nationals on the island by 1959.

But Japan has denied official responsibility for the Koreans on Sakhalin, citing a 1965 treaty in which the Seoul government promised not to make further compensation claims in return for a Japanese aid package of $800 million.

Some critics argue that the treaty doesn’t apply to the Sakhalin Koreans, who never regained their Korean citizenship.

Japan later chipped in 6.5 billion yen ($58 million) “on humanitarian grounds” to help the returnees from Sakhalin resettle in Korea.

Due to a shortage of funds, however, the returnees were allowed to bring their spouses only, leaving behind their children unless they were born before the end of the World War II in 1945.

Critics say the rule makes elderly Koreans make a painful choice between their family and a chance at life in Korea.

This article was originally posted on August 22, 2007, at the website of the Korean Overseas Information Service (KOIS), part of the South Korean Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The KOIS site includes other articles on “History and Truth.” Posted at Japan Focus on September 7, 2007.

William Underwood is a faculty member at Kurume Institute of Technology and a Japan Focus coordinator. He is the author of a series of Japan Focus articles on Chinese and Korean forced labor in wartime Japan, most recently Proof of POW Forced Labor for Japan’s Foreign Minister: The Aso Mines.