What the U.S. Government No Longer Wants You to Know about Nuclear Weapons During the Cold War

Edited by William Burr

[The National Security Archive has released an important series of documents revealing the reversal of several decades of efforts to make available for public scrutiny the numbers of US nuclear missiles during the early decades of the atomic era.

The complete report, and the supporting documents revealing both the numbers of weapons and their deployment, including the deployment of nuclear weapons in Asia and the Pacific, as well as evidence of recent policy shifts designed to suppress already available public information, are available.

The report confirms the larger pattern of closure of public access to official information that has been a hallmark of the Bush administration as it has moved to eliminate major arms control agreements of previous decades and step up US nuclear development and testing. MS]

Washington, D.C., August 18, 2006 – The Pentagon and the Energy Department have now stamped as national security secrets the long-public numbers of U.S. nuclear missiles during the Cold War, including data from the public reports of the Secretaries of Defense in 1967 and 1971, according to government documents posted today on the Web by the National Security Archive.

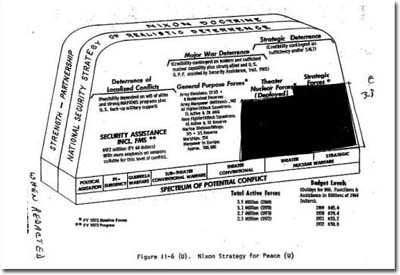

Pentagon and Energy officials have now blacked out from previously public charts the numbers of Minuteman missiles (1,000), Titan II missiles (54), and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (656) in the historic U.S. Cold War arsenal, even though four Secretaries of Defense (McNamara, Laird, Richardson, Schlesinger) reported strategic force levels publicly in the 1960s and 1970s.

Released in 1971

The security censors also have blacked out deployment information about U.S nuclear weapons in Great Britain and Germany that was declassified in 1999, as well as nuclear deployment arrangements with Canada, even though the Canadian government has declassified its side of the arrangement.

The reclassifications come in an environment of wide-ranging review of archival documents with nuclear weapons data that Congress authorized in the 1998 Kyl-Lott amendments. Under Kyl-Lott, the Energy Department has spent $22 million while surveying more than 200 million pages of released documents. Energy has reported to Congress that 6,640 pages have been withdrawn from public access (at a cost of $3,313 per page), but that the majority involves Formerly Restricted Data, which would include historic numbers and locations of weapons, rather than weapon systems design information (Restricted Data).

Documents posted today by the National Security Archive include:

* Recently released Defense Department, NSC, and State Department reports with excisions of numbers of nuclear missiles and bombers in the U.S. arsenals during the 1960s and70s.

* Unclassified tables published in a report to Congress by Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird as excised by Pentagon reviewers.

* A “Compendium of Nuclear Weapons Arrangements” between the United States and foreign governments that was prepared in 1968 and recently released in a massively excised version under Defense Department and DOE guidelines.

* Canadian and U.S. government documents illustrating the public record nature of some information withheld from the 1968 “Compendium.”

“It would be difficult to find better candidates for unjustifiable secrecy than decisions to classify the numbers of U.S. strategic weapons,” remarked Archive senior analyst Dr. William Burr, who compiled today’s posting. “This problem, as well as the excessive secrecy for historical nuclear deployments, is unlikely to go away as long as security reviewers follow unrealistic guidelines.”

“The government is reclassifying public data at the same time that government prosecutors are claiming the power to go after anybody who has ‘unauthorized possession” of classified information,” said Archive director Thomas Blanton. “What’s really at risk is accountability in government.”

Declassification decisions on U.S. nuclear weapons information by federal agencies have taken a surprising turn. Security reviewers are treating as “classified” information that has been available in the public record for decades. For years during the Cold War the U.S. nuclear arsenal included 1,000 Minuteman and 55 Titan II missiles; this information could easily be found in a variety of public record sources. For reasons that are truly perplexing, when the current reviewers open up archival documents from the Cold War, they are redacting those and other publicly-available numbers, even to the point of classifying parts of a public report by the Secretary of Defense [see examples in Part II). Excessive secrecy continues to abound in another category of historical nuclear information: the overseas deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons during the Cold War. Information on the deployments that has been publicly available for many years is also being classified by U.S. government agencies.

Members of the U.S. Air Force’s 71st Tactical Missile Squadron check a

nuclear-capable Mace MGM-13B missile on its launcher in a steel and

concrete underground hanger at Ramstein Air Force base in Germany,

1968. The Mace’s W-28 thermonuclear warhead had an explosive yield of

1.1 megatons. (Photo no. 112895, file 342B-ND-057-5, Still Pictures

Division, National Archives).

Government attempts to classify public-record information brings to mind the recent controversy over the reclassification of thousands of pages of documents at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The controversy was sparked by doubt whether many of the formerly open-shelf documents that the CIA and the Air Force had withdrawn from open records at NARA had any current sensitivity (some of the documents had been published by the State Department years earlier). Just as questionable is the Pentagon’s attempt at virtual reclassification of the numbers of Cold War strategic nuclear systems. During the 1960s and 1970s, Secretaries of Defense produced public reports showing that at the height of the Cold War, the United States had 1,054 intercontinental ballistic missiles (1,000 Minutemen and 54 Titan IIs) and 656 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). This and related information has also been available before in previously declassified documents, but now Pentagon officials excise the same numbers when they review documents. Although National Security Archive staffers have challenged the practice in mandatory review appeals, the number game continues to this day.

Another category of nuclear weapons information, the overseas deployments of the weapons during the Cold War, also raises questions about the standards used in declassification reviews. Since Fiscal Year 1999, Congress has authorized the Department of Energy to review formerly open-shelf records at NARA to locate and impound documents containing inadvertently released secret information about nuclear weapons. (Note 1) One of the classes of secrets that have been at issue in DOE’s review process has been the locations of the thousands of U.S. nuclear weapons that the U.S. Army, Air Force, and Navy deployed overseas during the Cold War. While government agencies have occasionally released information on the deployments, since the late 1990s DOE and the Defense Department have been working together to keep the information under wraps. As sensitive as information on the scale of the deployments was during the period of U.S.-Soviet confrontation, it is questionable whether all of it must remain classified. A recent massively excised “release” of a “Draft Compendium of Nuclear Weapons Arrangements” prepared in October 1968 by the Department of State’s Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs demonstrates the rigid approach that U.S. government agencies take to protect the secrecy of historical nuclear deployments.

This briefing book provides examples of government declassification decisions on questionable nuclear secrets: the numbers of strategic weapons systems and the locations of, and policies concerning, overseas deployments during the Cold War. While secrecy is likely to shroud the historic overseas deployments for some time, the hot light of publicity might halt the laughable practice of classifying public record information on the numbers of strategic weapons.

1.George Lardner Jr., “DOE Puts Declassification in Reverse,” The Washington Post, May 19, 2001, .

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 197 was posted at the National Security Archive website on August 18, 2006. Posted at Japan Focus on August 18, 2006.

For more information: Dr. William Burr, Thomas Blanton, 202/994-7000.