Japan-North Korea Relations—A Dangerous Stalemate

Wada Haruki

Global attention focuses on North Korea (the DPRK, or Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) and the crisis that envelops its nuclear and missile programs. A little-noted aspect of the crisis has been the rise of Japan to centre stage in the Security Council proceedings and in the formation of global understanding of the problem.

Less than a year ago Japan was the outsider at the Six Party talks on North Korea, blocking any agreement, refusing to meet its obligations under the agreements that were in due course reached in Beijing, and protesting vigorously, and eventually in vain, at the US decision to remove North Korea from the list of terror-supporting countries. From outsider at Beijing and in Washington under the late George W. Bush, Japan’s influence has soared under Obama. Though occupying only a temporary Security Council seat, secured by horse-trading with Mongolia, it has become in effect an honorary superpower, major architect of the Security Council presidential statement of 13 April and of Resolution 1874 of 12 June. For North Korea, nothing could be more galling than the awareness that its old nemesis and former colonial master now leads the world in denouncing and sanctioning it.

In the following essay, Wada Haruki, emeritus professor at the University of Tokyo and authority on the modern history of Korea, discusses the background to the present frozen and hostile relationship between the two countries. (GMcC)

1 What is the state of the Japan-DPRK relationship?

According to the materials of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, there are now in this world 194 countries – setting aside Taiwan, the Republic of China. Among these 194 countries Japan has diplomatic relations with all save one—the DPRK. And yet the DPRK is one of Japan’s closest neighbors, and one with which it has been closely tied throughout its history. In ancient times Japan was influenced culturally by the kingdom of Koguryo, which ruled in what is now North Korea. In late medieval times Japanese forces invaded North Korea and occupied Pyongyang for seven months in 1592—93. In the modern era Japan annexed Korea in 1910 and turned it into her colony until 1945. In the Korean war of 1950-53 Japan served as the most important air force and logistics rear base to US armed forces fighting against North Korea. US B-29 bombers flew every day from Yokota and Kadena bases, raiding North Korean cities and facilities. In 1977-1983 North Korean agents abducted up to two dozen Japanese citizens in order to conduct subversive activities in South Korea.

At present North Korea, the DPRK is the most hated and feared country for the majority of Japanese people. In their eyes, Kim Jong Il’s regime looks threatening and poor. More than 150 North Korean missiles are targeted at Japan, first of all at US bases and second at the Self Defense Force bases. Of course, North Korea’s nuclear tests have generated fear and anger in Japan. Such North Korean actions led Japan to ban all exports from North Korea and all visits of North Korean vessels and citizens to Japan. Our relations with North Korea may be worse now than ever.

This situation is dangerously abnormal. Without reliable relations with one’s neighbors, normal life becomes impossible. In order to secure safety, at a minimum right now it is necessary to start diplomatic negotiations to normalize relations with the DPRK. Actually, negotiations between the Japanese and North Korean governments on normalization started in 1991, 18 years ago. Japan’s Prime Minister visited Pyongyang twice in the last seven years, but in vain. This is an additional factor of abnormality in our situation.

Therefore we must think over the problem, “What is wrong with our attitude toward the Japan-DPRK relations?”

2 Koizumi’s Visit, 2002

On September 17, 2002, Prime Minister Koizumi surprised the international community by visiting Pyongyang. This unexpected turn of events was nevertheless the result of long, secret negotiations that began at the initiative of the North Korean side at the end of 2001. “Mr. X,” a North Korean who enjoyed the confidence of leader Kim Jong Il, and Tanaka Hitoshi, head of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asia-Pacific Bureau, had conducted negotiations patiently and came to an agreement named later the “Pyongyang Declaration”. This agreement was disclosed to some leading high officials of the Foreign Ministry only on August 21 and to Abe Shinzo, Deputy Cabinet Secretary, when he was accompanying Koizumi on the plane to Pyongyang [1].

We do not know when the United States government was informed of this agreement. Though Koizumi’s visit to Pyongyang was carried out with the consent of the United States government, full information was not given to the United States. It was a rare case of independent Japanese diplomacy.

At Pyongyang, the two leaders agreed to “make every possible effort for an early normalization of relations.” Koizumi expressed “deep remorse and heartfelt apology” for “the tremendous damage and suffering” inflicted on the people of Korea during the colonial era, while Kim Jong Il apologized for the abductions of 13 Japanese and for the dispatch of spy ships in Japanese waters. North Koreans informed Japan that 8 of 13 were dead and 5 survived.

North Korean Stamp to Commemorate the Koizumi Visit

Initially Koizumi’s diplomacy and the moves to normalize relations with North Korea drew a positive public response in Japan. But of course the families of the victims, informed that their sons or daughters were dead, were dismayed and reluctant to believe such information. Sukuukai (the National Association for the Rescue of Japanese Abducted by North Korea), headed by Sato Katsumi, an anti-DPRK activist, devised an argument which served as a way out of this crisis.

Sukuukai issued a statement on September 19, two days after the Koizumi visit, saying:

“There is no basis for the information on the survival or death of the abductees that the North Korean government provided to Koizumi during his visit. The Japanese government has yet to verify the accuracy of this information. Thus, there is a strong possibility that the eight people who are reported as dead may still be alive. Despite this, the Japanese government’s simply informing the families that these people are dead may increase the possibility that these victims, if indeed alive, will be killed.” [2]

Whether North Korea gave evidence of the deaths of the eight victims or not, Japan should have responded to its confession about their death with sincere attention. The Sukuukai argument was not logical. Sukuukai began to attack Foreign Ministry officials, especially Tanaka Hitoshi. He came to be called a traitor who betrayed the national interest. Unreasonable anti-DPRK feelings were provoked in Japan.

Three weeks after the Summit, five of the thirteen recognized abductees returned to Japan in a special plane. According to the agreement between the two governments, these five were to return to Pyongyang to work out their long-term future and that of their families. But their parents and brothers and sisters were not willing to allow them to go back to Pyongyang. The five finally made up their minds to remain and wait for their children in Japan [3]. What the Japanese government should have done at this moment was to apologize for violating the promise and to ask the North Korean government to allow the five to remain permanently in Japan. Instead, Tanaka Hitoshi was forced to say that there was no such promise and Abe Shinzo, to whom Koizumi entrusted this matter, began to issue highhanded and insulting demands for the return of the children of the Five.

The relations between two governments became hostile and Japanese national feelings toward North Korea deteriorated precipitously. Around this time Abe was saying that “In Japan there is food and oil, and since North Korea cannot survive the winter without them, it will crack before too long”.

Against this background US Assistant Secretary of State James Kelly’s visit to Pyongyang and his story of a North Korean uranium enrichment program played a decisive role in disappointing the Japanese aspiration for normalization of relations with North Korea.

After these four lost years, 2002-2006, Abe succeeded Koizumi as Prime Minister.

3 Japan’s policy toward North Korea—“Abduction Issue First”

Japan’s Policy toward North Korea was comprehensively defined by the Abe Cabinet in autumn 2006. Prime Minister Abe said in his policy speech to the Diet on September 29, 2006:

“There can be no normalization of relations between Japan and North Korea unless the abduction issue is resolved. In order to advance comprehensive measures concerning the abduction issue, I have decided to establish the “Headquarters on the Abduction Issue” chaired by myself, and to assign a secretariat solely dedicated to this Headquarters. Under the policy of dialogue and pressure, I will continue to strongly demand the return of all abductees assuming that they are all still alive. Regarding nuclear and missile issues, I will strive to seek resolution through the Six-Party Talks, while ensuring close coordination between Japan and the United States” [4].

Prime Minister Abe declared that the solution of abduction issue was “the most important problem our country faces” and appointed Cabinet Secretary Shiozaki Yasuhisa as Minister in charge and Nakayama Kyoko as Special Adviser to the Prime Minister on abduction issue. Just three days after the start of his Cabinet, Abe established a “Headquarters on the Abduction Issue” (hereafter: HAI) chaired by the Prime Minister and including all Cabinet members. It was a sort of an emergency form of the Cabinet.

The first meeting of the HAI, held on October 16, adopted a document entitled “Principles for measures to address the abduction issue”. In the preface phrases of Abe’s policy address were re-confirmed, such as “there can be no normalization of relations between Japan and North Korea unless the abduction issue is resolved,” and that the government united would seek to realize “the return of all abductees” alive.

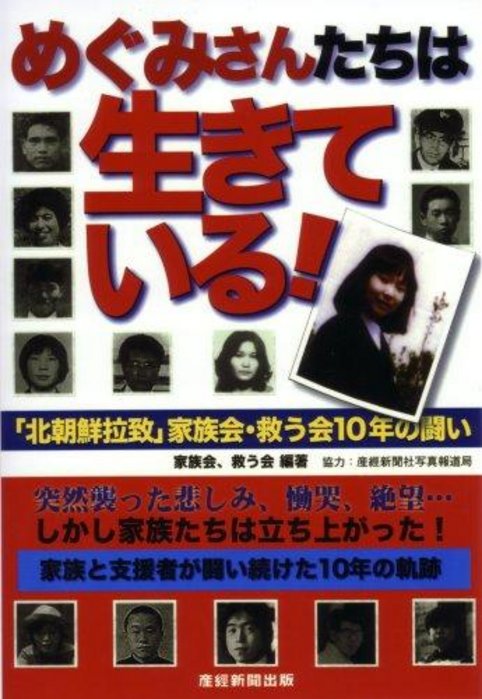

“Megumi, and the Other Abductees, Are Alive – The Record of 10 years of Struggle”

Sankei shimbunsha, 2007

Behind this latter phrase lies the notion that if North Korea could not provide clear evidence of the death of the victims Japan should assume all are still alive and demand the return of all abductees. This notion was promoted by Sukuukai in September 2002. At that time, such a view was shared only by victim families, but in December 2004, just after the DNA examination of the so-called Yokota Megumi bones, the Japanese government adopted it as official policy toward North Korea.

North Korea declared that 13 had been abducted, of whom 8 were dead and only 5 remained alive. Japan demanded evidence of death, but not receiving satisfactory answers, came to think the 8 all still alive and to demand their return. It was a jump in logic, inappropriate in diplomatic negotiations.

The first meeting of the HAI decided on the following six point program.

1. The Japanese Government will continue to call resolutely on North Korea to allow all abductees to return immediately to Japan, to reveal the facts behind the abductions, and to hand over those who carried out the abductions.

2. The Japanese Government has implemented a series of economic sanctions against North Korea. It will consider implementing further measures, in accordance with the future stance adopted by North Korea.

3. The Japanese Government will continue to implement strict legal measures. (Under this head, wholesale harassment was carried out of North Korean-affiliated Koreans in Japan and their association, Chongryon, by the strict implementation of legal measures.)

4. The HAI will further enhance efforts to raise the awareness of the Japanese people regarding the abduction issue.

5. The HAI will continue to promote every effort to study and investigate other cases in which the abduction of Japanese citizens by North Korea cannot be ruled out.

6. The HAI will further strengthen its international collaborative efforts in multilateral forums such as the United Nations, and through close cooperation with concerned countries.

HAI has a secretariat, with a staff currently of around 40 from related Ministries and the Police agency and a budget of 226 million yen (2006), 480 million yen (2007), and 677 million yen (2008), not including personnel. In 2008, 75 million yen was spent on policy studies, 100 million on intelligence services, 110 million on public relations and education, 110 million on activities abroad, 146 million on broadcasts to North Korea [5]. Around 200 million yen for the 40 officials is paid by their home ministries or police agencies. Therefore, if personnel expenditures are included, the HAI budget amounts to 900 million yen.

HAI’s main activities are propaganda at home and abroad on the awfulness of the North Korean crime of abduction and on North Korean cruelty. Posters, TV commercials, pamphlets, a DVD program entitled “Abduction—An Unforgivable Crime” have been produced and circulated. The documentary film “Megumi” and the animation film “Megumi” were bought up and shown, especially to high and middle school boys and girls. A broadcast to North Korea entitled “Wind from home towns” was regularly repeated. Together with local governments in Japan, HAI organizes various events during the “North Korean Human Rights Abuses Awareness Week” held every year from December 10th to 16th, and also occasional international symposia and national rallies.

One of HAI’s functions is to liaise between Kazokukai (The Abductee Families Association), the abducted families and the government. Abducted families regularly meet the Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister through HAI. The activities abroad of abducted families are attended by officers of HAI and supported financially. Thus HAI tends to cope with the abduction issue monopolistically, taking over some of the diplomatic functions of the Foreign Ministry. The result is a phenomenon of dual diplomacy.

HAI’s activities are combined with economic sanctions against North Korea, decided in October 2006 and renewed or intensified every half year since then. The main content of economic sanctions is prohibition of North Korean exports to Japan and North Korean vessels’ visits to Japan. As these measures were adopted and carried out only by the Japanese government, their effects are believed to be not so serious. But it is a fact that the ban on Mangyongbong Ferry between Niigata and Wonsan, which was used mainly by Koreans in Japan, caused palpable damage to them.

Besides these measures, the direct harassment of DPRK–affiliated Koreans in Japan and their organization, Chongryon, was carried out systematically by police and local governments in the name of strict implementation of the rules. This policy was promoted and led by the Director of the Police Agency, Uruma Iwao. Uruma said overtly that it was the police’s task to make North Korea enter into negotiation with Japan [6]. In the case of Koreans in Japan, even small violations of laws were not overlooked. Police search houses and arrest suspects. Newspapers write inflated articles. Tax exemptions which Korean associations and schools had enjoyed for many years were re-examined and abolished as illegal. These were all petty harassments which outraged minority groups and created internal cleavages.

Prime Minister Abe’s policy was expressed in Japan’s approach to the Six Party talks. In February 2007 it was decided that during the Initial Action phase and the next phase energy assistance up to the equivalent of 1 million tons of heavy fuel oil would be provided to the DPRK. Five countries were each expected to provide 200 thousand tons of heavy fuel oil. Japan, however, refused to give its portion because the abduction issue was not solved. In October 2008 the U. S. government approached the Australian government to ask it to contribute in place of Japan. North Korea at that time said that Japan need not remain in Six Party Talks.

Prime Minister Abe’s HAI policy can be characterized as an Abduction Issue First policy.

4 Prime Minister Fukuda’s Failure and Exodus

In September 2007 Abe suddenly resigned, and was replaced as Prime Minister by Fukuda Yasuo. In his campaign speech Fukuda clearly distinguished his policy line on North Korean issue from Abe’s. In his October 1 policy address to the Diet, Fukuda stated:

“The resolution of issues related to the Korean Peninsula is indispensable for peace and stability in Asia. For the denuclearization of North Korea, we will further strengthen coordination with the international community, through fora such as the Six-Party Talks. The abduction issue is a serious human rights issue. We will exert our maximum efforts to realize the earliest return of all the abductees, settle the “unfortunate past,” and normalize the relations between Japan and North Korea” [7].

Fukuda put the nuclear issue as his top priority and sought the solution of abduction issue in the process of normalization of relations with North Korea. During his administration, no meeting of the HAI was held. It seems that Prime Minister Fukuda was not even conscious of being Chairman of this headquarters. Yet he could not actually abolish the HAI and kept the position of Nakayama Kyoko, Special Adviser on the Abduction Issue, intact. HAI’s budget and its staff was maintained and continued to expand.

As the Fukuda Cabinet faced continuously various annoying political issues, it could not tackle the North Korean problem. But in the spring of 2008 a new tide came in. Both in ruling parties such as the Liberal-Democratic Party and Komei Party, and in opposition parties such as the Democratic Party and Social-Democratic Party, committees and study groups committed to tackling the Korean peninsula issue were organized. Soon a Parliamentarians’ League for Promotion of Japan-DPRK Normalization was inaugurated on the basis of such committees and study groups. Backed by such moves, Saiki Akitaka, Head of the Foreign Ministry’s Asia-Pacific Bureau, negotiated with Song Il-ho, North Korean Ambassador, twice in June and August, 2008. They managed to come to agreement each time on partial removal of economic sanctions and re-investigation of the abducted victims.

In negotiations in Beijing on June 11-12, 2008 the North Korean ambassador stated that North Korea would no longer contend that the abduction issue was solved, and promised to re-investigate the abducted victims. He stated that return of the hijackers of the JAL plane Yodo (1970) would be promoted. A Japanese representative stated that the prohibition of visits for government employees and the ban on charter flights would be lifted and that North Korean vessels would be allowed to enter Japanese ports in order to carry humanitarian aid [8]. However, when this agreement was made public in Japan, reaction was so strong that Cabinet Secretary Machimura hurried to retreat and stated that such sanctions would only be lifted after checking the results of the re-examination. North Korea rejected this.

But on August 11-12 Saiki and Ambassador Song met again in Shenyang and came to another agreement: when the North Korean side informed Japan about the start of the committee for re-investigation into the victims of abduction, Japan would lift the prohibition on visits by government employees and the ban on charter flights. It is amazing that the North Korean side withdrew its demand for the right of its vessels to visit Japan. But in the beginning of September Prime Minister Fukuda showed a lack of responsibility by suddenly resigning, and the second agreement collapsed.

From October 18 to 22, I visited Pyongyang (as Secretary-General of the National Association for Normalization of Japan-North Korea Relations) to meet North Korean participants in Japan-DPRK negotiations. Ambassador Song did not appear, but his assistant Yi Byung dok did. He explained that in the June negotiations the Japanese side had promised in future to behave carefully so as not to irritate the North Korean side and not to use the abduction issue for political purposes. He further said that in the August negotiations the Japanese side had pledged to keep its promise in the name of Prime Minister Fukuda. “Therefore,” he said, “we dared to come to the second agreement”.

This is the story from the North Korean side. I could not hear the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s response. But it is natural to imagine that on hearing that Japan was ready to change its attitude fundamentally, the North Korean side also changed its stand that the abduction issue was already solved. Saiki, representative of Japan, after the June negotiations explained that “we were able to have penetrating discussions about important issues between Japan and DPRK in a sincere and constructive atmosphere”. That is to say that the June and August negotiations were carried out by Prime Minister Fukuda and Foreign Ministry in different spirit from the HAI line. With Fukuda’s departure, however, the possibility of change disappeared.

5 Popular Consciousness and the Mainstream Media

While Fukuda was Prime Minister, he was under great pressure from the people’s consciousness and from mainstream media. The Japanese people have deep sympathy toward the abducted victims and their families. They are inclined to think that the abduction issue is the most important task Japan faces and are not willing to hear dissident opinions about this issue. Such prevalent social atmosphere binds equally government, Diet members, and Foreign Ministry.

The mass media tends to unite in a hard-line attitude. TV news shows in particular are sensational. The Abe Cabinet ordered Nippon Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) to step up its coverage of the abduction issue in its overseas broadcasts. This order exerted influence on NHK generally and NHK’s regular news at 19:00 began to cover the abduction issue constantly. Almost every Sunday this news covers the activities of abducted families, especially Yokota Megumi’s parents. When Prime Minister Fukuda resigned, in the main national NHK TV news at 19:00 it was the representative of Kazokukai (Association of Abducted Families), Iizuka Shigeo, who appeared first to assess the event. He was followed by the President of the Federation of Economic Organizations, Mitarai Fujio. Nowadays the leaders of Kazokukai, IIzuka and Masumoto Teruaki (Secretary General), are first priority in newspapers and on TV programs as commentators on North Korean matters. Their comments are always fiercely anti-DPRK and in favor of increased economic sanctions.

The newspaper Asahi Shimbun has been known to be liberal. This company organized exhibitions of Yokota Megumi’s photos in all parts of Japan during the past three years, with a late November exhibition in Tokyo to crown the enterprise. On November 23 Asahi Shimbun’s well-known column “Tensei Jingo” introduced this exhibition and finished with the following words: “A mother of a neighboring country is saying such words full of sorrow and anger, but a dictator still survives there.” [9] The mother, Yokota Sakie, has become a national heroine, fighting bravely against North Korea to get back her abducted daughter Megumi.

Yokota Megumi’s Parents, Shigeru and Sakie

On April 25, 2009 in the late night TV discussion program “Asamade Nama Terebi” the well-known anchor man, Tawara Soichiro, said, “The Japanese Government negotiations with North Korea are premised on the assumption that Yokota Megumi and Arimoto Keiko are alive. North Korea, however, has repeatedly said that they are not alive. And the [Japanese] Ministry of Foreign Affairs knows that they are not alive. But to negotiate on the understanding that they are not alive would be to invite severe criticism from public opinion and the mass media.” Tawara’s informant, he said, was a high-ranking Ministry of Foreign Affairs official (No. 2 or No. 3). Angry at this, Kazokukai demanded an apology from Tawara and his TV company.

It is difficult to examine the problem of life and death of abducted victims in public media or in parliament. Beneath the understandable anguish of the victim families a suspicion that their sentiments might have been manipulated, even by government, begins to surface. Yokota Shigeru, father of Megumi, spoke at a press conference on May 11:

“There is no evidence whatever of [my daughter’s] death. So long as there is no objective proof, naturally we have to proceed on the assumption that she is still alive. It would be outrageous if it turned out that negotiations are being prolonged even though she is dead. As her family, we want to know the truth. If she really is dead, then there is nothing for it but for us to accept that, but if it turns out that the government, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has been negotiating as if she were still alive while knowing her to be dead, that would be an extremely serious matter.”

If it is the case that the Japanese government has been manipulating the media and public opinion, and even the victim families, by concealing crucial information, and that political and media groups have been uncritically swallowing the government’s line, that would indeed be “outrageous.” Perhaps we simply have to wait for a small boy to say that “the king is naked.”

6 Prime Minister Aso’s Return Bout

The Bush administration’s decision to finally lift the terror-supporting label from North Korea hit the Aso Cabinet within days of its launch. On October 11, 2008 this decision was made public and North Korea, welcoming this action of the US government, announced that disablement of nuclear facilities at Yongbyon would be resumed. Given only 30 minute notice of the announcement, Prime Minister Aso and his government received a severe shock. Masumoto, Secretary General of the Abducted Families Association, said that it was “a betrayal, which shows the US government does not care for Japanese lives in the name of own national interest” [10]. The Yomiuri featured the headline “Defeat of Japanese Diplomacy” for its October 13 issue [11].

The Aso Cabinet reacted to this shock by reviving the HAI. On October 15 the second meeting of the HAI chaired by Prime Minister Aso was held and it re-confirmed the Abe document “Principles for measures to meet the abduction issue”. At the same time economic sanctions were renewed for another half year. North Korea thereupon effectively cancelled its agreement with the Fukuda government.

Thereafter there have been no negotiations between two countries. We are facing a true stalemate. The Aso Cabinet has been annoyed by the falling percentage of support in public-opinion polls. Prime Minister Aso has made desperate efforts to prolong his Liberal-Democratic Party administration by every means. To a Prime Minister in such straits, the North Korean announcement in March of intention to launch a rocket for a communications satellite provided a big chance to project the image of reliable government.

Prime Minister Aso immediately on March 13 stated that even if it was a satellite launch, it would be a breach of U.N. resolutions, and that Japan was determined to cooperate with the United States and the ROK in promoting a Security Council resolution imposing sanctions [12]. He ordered any possible falling objects from the North Korean missile flying high above Japan to be destroyed, allocating PAC3 rockets in several places of Japan. People’s apprehensions were very much heightened. The March 28 issue of the Mainichi wrote that Prime Minister Aso wishes to raise the Cabinet’s reputation by showing its crisis-control ability [13]. When North Korea launched a rocket on April 5, the Japanese government called upon the Security Council to convene an urgent meeting and joined with the United States to call for a resolution of further sanctions. Prime Minister Aso persuaded Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao to join Japan’s resolution [14]. Though a new Security Council resolution was not obtained, Japan succeeded in getting a Security Council chairman’s Statement that recognized North Korea’s launch as a violation of Security Council resolution 1718. Further sanctions against North Korea followed.

Japan itself decided to renew the existing economic sanctions for another year and adopted a new sanction. Each traveler to North Korea could hitherto take one million yen with him, but now was to be allowed to take only 300 thousand yen.

On the eve of the North Korean launch Japanese specialists without exception thought that North Korea wanted to achieve a repetition of the process after the launch of the Taepodong missile in September 1998, in other words, to start a process akin to the second Perry process. I agreed with my colleagues, but I attached greater importance to the North Korean internal situation. To Kim Jong Il’s regime the rocket launch on April 5 was rather an action to demonstrate Kim Jong Il’s power and the national integration around his leadership.

The ailing leader Kim Jong Il came to realize that the country’s internal situation had declined and many rumors of possible successors spread during his absence from the political scene. After recovery, he began his pilgrimage to various places in the country to show that he is alive and to remove people’s apprehensions. On March 8 an election of deputies to the Supreme People’s Assembly was held. The rocket for a communications satellite was launched on the eve of the opening of the new Supreme People’s Assembly. On April 9 the Assembly opened and a new Defense Committee was elected. The portraits of all members of this highest power organ were published in the April 10 issue of Nodong Shimbun [15]. The launch of the rocket was tightly linked with this power ceremony.

Japan paid no attention to this situation and led an international campaign against North Korea. The accusations of the international community, the Security Council chairman’s statement and the new sanctions damaged Kim Jong Il’s prestige. North Koreans were so infuriated that on April 30 the press officer of the North Korean Foreign Ministry issued a statement saying that if the Security Council did not apologize for freezing the assets of three North Korean companies, North Korea would take measures for self defense, such as nuclear tests and the launch of trans-continental ballistic missiles. This means that the actions taken by the Security Council after the launch of the rocket on April 5 rather than having a positive effect instead worsened the situation.

On April 17, two conferences were held in Tokyo at the initiative of the Japanese government: the Pakistan Donors Conference and the Friends of Democratic Pakistan Group Ministerial Meeting. Prime Minister Aso promised to give 100 million dollars in aid to Pakistan, saying “Without the stability of Pakistan, there can be no stable Afghanistan, and vice versa”. No doubt this is necessary aid. But Pakistan possesses nuclear weapons and is still developing missile technology, and Pakistan provided uranium enrichment technology to North Korea. There are many problems in this country. Japan took the lead in helping Pakistan to overcome social unrest without saying that first it had to abandon its nuclear weapons program. We can not deny that this was a double standard.

7 The Obama administration and North Korea

Obama diplomacy toward Northeast Asia has not yet started in full scale. In its policy priority the position of Northeast Asia does not seem high. Iran, Afghanistan and Iraq problems may top President Obama’s list. Perhaps the Cuban problem ranks higher than North Korea. This is to be understood and supported. And in the beginning of April during his visit to Prague, he proposed a bold plan for nuclear disarmament. This address touched the Japanese people by such words, “As the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act”. This was great indeed.

But unfortunately in the very morning, April 5, when President Obama was going to make the address, North Korea launched a rocket over Japan. The President was busy forming his attitude to this action of North Korea. Finally in his address President Obama included some remarks about North Korea. He said that North Korea had broken the rules once more and that violations must be punished. “North Korea must know that the path to security and respect will never come through threats and illegal weapons”. I think that the President of a country armed with long-range and middle-range nuclear missiles should not call a North Korean rocket “illegal”. President Obama talked as if he were a high school teacher rebuking a boy in his class. In his address Obama tried to persuade the Iranian government, but not the North Korean government.

Former President George Bush liked independent actions and lifted the terror-supporting label from North Korea in spite of serious Japanese opposition. President Obama, however, favors international cooperation and chose to move against the North Korean launch in close cooperation with Japan and the ROK. Japan and the ROK now have no diplomatic contact with North Korea. Therefore, if the US wishes to cooperate closely with these two countries, it can do so not by dialogue but only by increasing pressure on North Korea. The result of international cooperation undertaken without adequate thought as to its consequences was the second North Korean nuclear explosion on May 25.

Now is the time for strong and developed countries to examine soberly the effect of their sanctions and to find ways to negotiate with North Korea, a small nation, irritated to the utmost, but aspiring to national security and economic development in its own way.

Notes

1. Yomiuri Shinbun seijibu, Gaiko wo kenka nishita otoko—Koizumi gaiko 2000 nichi no shinjitsu, Shintyosha, 2006, pp. 26, 32.

2. Araki Kazuhiro (ed.), Rachi kyushitsu undo no 2000 nichi 1996-2002, Soshisha, 2002, pp. 479-481.

3. Hasuike Toru, Rachi—Sayu no kakine wo koeta tatakai he, Kamogawa shuppan, 2009, pp. 31-33.

4. Asahi Shimbun, September 30, 2006.

5. Information from Aoki Osamu.

6. Aoki Osamu, “Abe seikenka, tai tyosensoren atsuryoku seisaku no jittai,” Sekai, 2008, No. 7, p. 153.

7. Asahi Shimbun, October 2, 2007.

8. Asahi Shimbun, June 13, 2008.

9. Asahi Shimbun, November 23, 2008.

10. Mainichi Shimbun, October 12, 2008.

11. Yomiuri Shimbun, October 13, 2008.

12. Asahi Shimbun, March 13, 2009.

13. Mainichi Shimbun, March 28, 2009.

14. Asahi Shimbun, April 10, 2009.

15. Nodong Shinmun, April 10, 2009.

Wada Haruki is Emeritus Professor of Tokyo University and author of Kin Nissei to Manshu Konichi Senso (Kim Il Sung and the Manchurian Anti-Japanese War, 1993), Chosen Senso zenshi (A Complete History of the Korean War, 2002), Kita Chosen – Yugekitai kokka no genzai (North Korea –Partisan State Today, 1998), Chosen yuji o nozomu no ka (Do we Want a Korean Emergency? 2002) and Dojidai hihan – Nicho kankei to rachi mondai (Critique of Our Own Times – Japan-North Korea Relations and the Abduction Problem, 2005). He is also Secretary-General of the National Association for Normalization of Japan-North Korea Relations.

This is a revised and expanded version of the talk he delivered on 5 June 2009 at the conference on “North Korea – Nuclear Politics” at the University of Washington, Seattle.

He is the author of the following Japan Focus articles on relevant themes:

Maritime Asia and the Future of a Northeast Asia Community (link)

The North Korean Nuclear Problem, Japan, and the Peace of Northeast Asia (link)

Recovering a Lost Opportunity: Japan-North Korea Negotiations in the Wake of the Iraqi War (link)

The Strange Record of 15 Years of Japan-North Korea Negotiations (link)

Japan-North Korea Diplomatic Normalization and Northeast Asia Peace (link)

Recommended citation: Wada Haruki, “Japan-North Korea Relations—A Dangerous Stalemate,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 25-2-09, June 22, 2009.