Militarism and Anti-militarism in South Korea: “Militarized Masculinity” and the Conscientious Objector Movement.

Vladimir Tikhonov (Pak Noja)

Korea – “a national defense/conscription state”

It is a well-known fact that warfare and obligatory military service system long played decisive role in the formation of modern nation-states, first in Europe and later elsewhere in the world. While externally the military prowess of a given state was (and still is) decisive for defining its place in a competitive international system explicitly based upon an equilibrium of military force and hegemonic interstate relations,1 internally conscription-based national armies formerly served as main pillars of the state, linking conscript-age able-bodied males with the nationalist ethos1 and acculturating them to views and practices often referred to as “militarized masculinity culture”. “Militarized masculinity”, both in the conscription states and in states possessing large-scale military but relying upon a volunteer force in peacetime, usually involves both a gendered view of the world in which the able-bodied man, the “defender of the fatherland”, was unconditionally privileged over women, defined either as sexualized objects or as child-rearing “mother of the nation”, and a shared feeling of superiority towards men unfit for or unwilling to engage in combat (handicapped, conscientious objectors, etc.).2 Examples of modern states which chose to define their whole able-bodied male citizenry as potential soldiers and use conscription as the primary instrument of “creating nationals”, include revolutionary and post-revolutionary France (which began the history of modern conscription by declaring the levée en masse on August 23, 1793), and the Prussian state, which began introducing French-style conscription practices after suffering a defeat at the hands of Napoleon’s conscript army in 1806-1807.3 In more recent times, the state of Israel successfully used a comprehensive conscription system applicable to both men and women. The conscription system inculcated Zionist ideals and the newly-forged Israeli national identity, as well as a siege mentality based upon the imperative of the “national defense” against the demonized Arabic/Muslim world, into the minds of a very heterogeneous body of citizens,4 In South Korea too, as we will see below, conscription provides an ideological fiction of equality, the exclusion of women from the conscription system and, consequently, much more manifestly the “hegemonic masculine” character of the army being an important difference.

While the classical militarized masculinity of the nineteenth century conscription states tended to grant able-bodied male “nationals”, as potential soldiers, a privileged place in the “national” discursive hierarchy, it marked all resisters and evaders, actual and potential, either as ideological delinquents lacking loyalty to the “nation”, or as moral delinquents placing their personal well-being above “national interests”. Both resisters and evaders became an easy target for often extremely violent in-group exclusion, which was supposed to “strengthen the national spirit” and prevent any further deviations from dominant ideological and behavioral forms. In heavier militarized and illiberal states like pre-World War I Germany, predominantly religious military objectors – the members of such minority peace churches as the Mennonites and Adventists – were subject to routine abuse, imprisonment and scornful press coverage, as “non-patriots”.5 In France after defeat in the war with Germany in 1870-71 and before World War I, draft resistance was viewed as sacrilege, unacceptable rebellion against basic Republican values,6 While the “official” nationalisms in pre-World War I France and Germany used each other in order to create an image of an implacable external enemy, all those deviating from the norms of militarized nationalist masculinity were conceptualized as an internal threat to the nation’s defense and its very existence. The negative otherization of all who were unwilling to conform to the dominant militarist ethos became an organic part of the general nationalist worldview of continental 19th century European conscription states. A similar worldview has been used by the South Korean elite in order to consolidate society on the anti-communist and developmentalist platform, create a climate of uniformity and conformity and prevent the emergence of deviations from dominant modes of thinking and behavior.

As is the case with many other modern states, South Korea’s (hereafter referred to as Korea, except to differentiate South and North Korea) officially defined “nation” and mainstream, establishmentarian nationalism are inseparably connected to universal male conscription. While the institutional history of conscription in Korea is comparatively short – as explained below, it was introduced by the Japanese colonial authorities in 1943 – its discursive history is much longer. Conscription as the cornerstone of the military strength of the continental European powers was repeatedly mentioned in the publications of Korea’s earliest modern newspapers, Hansǒng Sunbo (October 30, 1883 – August 21, 1884) and Hansǒng Chubo (January 25, 1886 – July 14, 1888). One of the young reformist intellectuals charged with editing Hansǒng Sunbo, Yu Kiljun (1856-1914), included a detailed account of the conscription system in his encyclopedic Sǒyu Kyǒnmun (A Record of Personal Experiences in the West). Explaining that, unlike the continental European countries, the US and Britain used voluntary recruitment in peacetime, he also emphasized the “warlike spirit” of the Anglo-Saxon countries by adding that Britons and Americans “receive military training when they are not busy, in such a manner that all citizens become soldiers”. He stressed also that conscription of the French or German type “equally makes both noble and base, rich and poor join the colours” and that the essence of keeping a modern standing army, conscript or voluntary, is in training and disciplining the soldiers, singling out the Japanese conscript soldiers, “known for sometimes getting into trouble with the police” as not yet well enough trained.7 Modern military – and the continental conscript armies were obviously seen as among the predominant types of modern military – was viewed by Yu as one of the main components of “civilization”. These views were essentially shared by the influential courtier and diplomat, Min Yǒnghwan (1861-1905), who concluded that universal conscription made Bismarckian Germany the strongest state on the continent. On October 21, 1896, he urged king Kojong to follow the example of the Russians, who strengthened themselves by introducing conscription, by introducing it, together with modern schooling for both sexes, into Korea – even though many other “Western customs” could not be introduced.8

Alarmed by the Russian advance into Manchuria in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, Kojong soon decided to follow this advice and had the General Staff (Wǒnsubu) draw up a draft of a conscription edict – only to be thwarted in August 1901 by objections from certain (unnamed) senior bureaucrats.9 On the urging of his closest advisers,10 Kojong managed, however, to override the objections of conservatives, for whom the principle of universality of modern conscription looked dangerously close to the “undesirable” idea of civic equality, and ultimately promulgated the conscription edict on March 15, 1903. The edict represented a compromise of sorts, as modern conscription was explained as “restoration” of a purported “ideal” Confucian military system, in which “military affairs and agriculture were the same, and all four classes of the subjects learned military skills” and the “conscription rules of various countries” were referred to only in passing.11 However, the edict was never realized in practice, due to administrative shortcomings and chronic financial deficits.12 The Korean state was unable to render effective military resistance to Japanese troops, who occupied the country without a single shot being fired at the start of the Russo-Japanese War in February 1904, Korea’s relatively small professional army, formally numbering around 16,000 officers and men, was gradually reduced in size under Japanese pressure, before being forcibly dissolved on August 1, 1907.13 As Korea was deprived of its sovereignty and became a protectorate of Japan on November 17, 1905, hopes that the government would establish a meaningful conscription system, disappeared. However, in many cases nationalistic educators were attempting to take the matter into their own hands and provide the boys in the newly established “modern” schools with some amount of basic military training befitting “patriotic nationals”. Pyongyang’s Taesǒng School, established on September 26, 1908, by the noted Protestant nationalist educator and politician An Ch’angho (1878-1938), not only had “military gymnastics” on its curriculum for all 3 years, but also treasured the custom of periodically arousing its boys on nights for harsh training sessions, which sometimes included marching barefoot in the snow.14 “Warlike spirit” was generally seen by the intellectuals in the early nationalist milieu as a crucial component of modern life, “Spartan training” in the schools being considered the second best choice in a situation where conscription was not possible.

After Japan’s full annexation of Korea in 1910, the military and/or physical training of Korean youth remained one of the main concerns of An Ch’angho, now an exiled, mostly US-based nationalist activist. He founded the Young Korea Academy (Hǔngsadan) in San Francisco on May 13, 1913, basing it on the Spencerian idea of the “harmonious development of intellect, morals, and body” which was widely popular in Korea in the 1900s. Its “Constitution” (yakpǒp) lists training in military gymnastics or another sort of sports as a condition for membership.15 On April 29, 1920, An Ch’angho, then in Shanghai in connection with the organization of the Korean Provisional Government (where he was appointed in succession as Minister of the Interior, Acting Prime- Minister, and Labour Office Director), organized the Far Eastern Committee (Wǒndong Wiwǒnbu) of the Young Korea Academy, which had its own Sport Section (Undongbu) and routinely included sport competitions (undonhoe) in its regular meetings.16 While considering “preparations” and “cultivation of strength” for Korea’s independence in the future as its first priority, An Ch’angho did not exclude a military option, and mentioned in his famed 1920 New Year Speech (Sinnyǒnsa) that, in order to prepare for an eventual “war for independence” the émigré Koreans, men and women, had to realize the “principle of universal military duty (kaebyǒngjuǔi) and spend at least one hour daily in military training. An concluded that “those who do not learn military skills are not Koreans. (…). Those who do not train in military skills oppose the principle of universal military duty. Those who oppose the principle of universal military duty oppose the war for independence. And those who oppose the war for independence are oppose independence”.17 Conscription, together with tax-paying, was proclaimed the main duty of Korea’s (male) citizens in the “Charter” (Hǒnjang) published by the newly-established Shanghai Provisional Government on April 11, 1919, and was mentioned in most projects for Korea’s future statehood worked out by the Provisional Government and the groups affiliated with it.18 However, all the military units organized by the Provisional Government from October 1938 onwards in order to assist China’s Nationalist government in its struggle against Japanese invasion, were voluntary:19 the Provincial Government had no administrative apparatus at its disposal to conscript Korean residents of China.

While An Ch’angho’s position on universal military training for Korean emigrants was hardly more than a declaration of principle, another prominent nationalist in exile, Pak Yongman (1881-1928), undertook to realize the dream of the “people in arms” – at least, on the level of one small-sized community. Having arrived in the US in February 1905, Pak, at that time politically and personally allied with Syngman Rhee (Yi Sǔngman, 1875-1965), promptly established himself as one of the leaders of the Korean-American community, and founded in June 1909 a Boys’ Military School (Sonyǒnbyǒng Hakkyo) in Kearney, Nebraska. He hoped this would develop into “Korea’s West Point”.20 In April 1911, while studying at the University of Nebraska, Pak wrote and published in the Korean-American newspaper Sinhan Minbo (which he edited) his treatise on the necessity of conscription, entitled On Universal Military Duty (Kungmin Kaebyǒng non, republished by America-based Tongnip between April 11 and August 22, 1945). Pak described war as inevitable due to the inescapability of the “struggle for survival”, and emphasized that conscription, whose origins he traced back to ancient Sparta, was the only way to respond to the challenges of the “commercial age”, when inter-nation competition intensified to the degree that “one is necessarily attacked by others unless one attacks them first”.21 After moving to the biggest center of Korean-American life, the Hawaii Islands, in early December 1912, Pak Yongman succeeded in establishing a larger (180-strong first enrolment) Korean military school. But by 1915, he had run into a conflict with his erstwhile friend Syngman Rhee over the finances of the Korean-American community. Rhee, a moderate who did not anticipate a “war for independence” in the foreseeable future, and viewed the attainment of independence as first and foremost a diplomatic task, wanted to use the funds for educational purposes. Pak Yongman’s ultimate defeat in this conflict shows that the “militarization” of the Korean-American society was hardly a popular priority among America-based Koreans in the 1910s. However, the belief that military training, together with regular schooling, was essential in creating worthy “nationals” (kungmin) seemed to be widespread.22

While Korean émigrés in the US or China were free to elaborate publicly on the virtues of conscripting and drilling Korean youth, and even to organize some model drilling centers, the intellectuals of colonial Korea, writing in heavily censored newspapers and journals, had to limit themselves to glorifications of Korea’s “warlike” past and appeals to Korean youth to improve their physical condition. Yi Kwangsu (1892-1950), a famous novelist and one of An Ch’angho’s prominent disciples, wrote in his Minjok Kaejoron (On the reconstruction of Korean Nation: Monthly Kaebyǒk, May 1922 issue) that “remaking” Koreans into modern “nationals” would require not only a library and school, but also a stadium for every county – together with mass-production of hygiene- and sports-related books.23 Sports were seen as an opportunity to produce a strong and disciplined citizenry and were one of the main foci of nationalist activities well into the late 1930s. However, discussions about conscription emerged in earnest when Japan, in dire need of new recruits after having launched full-scale invasion of China in 1937, in 1938 allowed Koreans to “voluntarily join the Imperial Army”. The Korean Education Law (Chosen Kyōiku rei) was also revised for the third time, introducing a much stronger military element into school curricula. While the decision to switch to wholesale conscription of Korean youth was finally taken by the Japanese government only on May 8, 1942,24 there was already an atmosphere of “all-out mobilization” in the late 1930s. Many Korean nationalist intellectuals, partly under pressure, partly based on their own racialized, Social Darwinian vision of the world, came to see Japan’s expansion abroad and its officially proclaimed policy of naisen ittai (“Interior [Japan] and Korea as one body”) as a certain form of fulfillment for Korea’s own dream of national greatness and a world-historical role. They voiced support for Korean recruitment into the Japanese army, often advertising for the Japanese military.25 So, while hardly enjoying popularity among ordinary Koreans, conscription became an article of the intelligentsia’s nationalist faith – conscripting or providing voluntary military training to émigré Koreans being an important part of the nationalist exiles’ plans for restoration of the nation’s sovereignty. Conscripting and disciplining Korean masses was the proclaimed wish of “pro- Japanese” colonial nationalists in the late 1930s-early 1940s, who, for a variety of reasons, came to view Koreans as a part of the bigger “Japanese race” and Japanese state. Although not implemented in Korea until the mid-1940s, it became a central part of the Korean discourse on modernity.

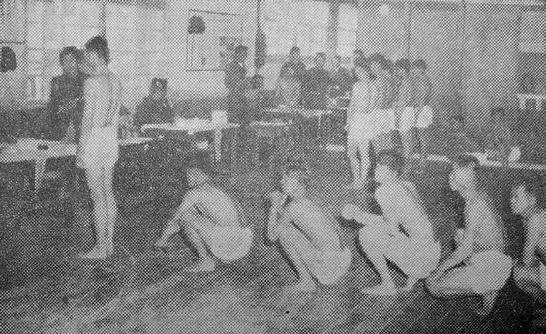

Korean youths conscripted by the Japanese authorities in the last years of the Pacific War

Conscription, first applied to Korean subjects of the Japanese Empire by Japanese colonial authorities in 1943 (promulgated March 1, effective August 1), was reintroduced soon after the establishment of the post-colonial Korean state on August 15, 1948. The first Military Duty Law (pyŏngyŏkpŏp), promulgated on August 6, 1949, drew largely on colonial precedents and continental European (German and French) models, putting all male citizens under the age of 40 under service obligations, requiring those whose obligations were unfulfilled to return from sojourns abroad before reaching the age of 26 (and prohibiting anybody above this age from traveling abroad until fulfillment of the service obligations). Exceptions were only made for those declared medically unfit, criminals, or delinquents.26 In anticipation of the coming all-out conflict with the competing regime in the Northern part of the peninsula and wishing to “consolidate” the militaristic nationalist platform and crush discontent among citizens at official corruption and the dire socio-economic situation, the Syngman Rhee regime began from an early point to militarize the schools as well: on December 26, 1948, regular military exercises were introduced in all schools above the middle level.27 In the beginning of the Korean War, on December 1, 1951, all male Korean students on the high school level and above were proclaimed soldiers of the “student army” (haksaenggun), to be drilled by active-duty officers on a regular basis; on April 1, 1953, it was declared, in the “Rules for the Execution of the Order on the Conduct of the Student Army Drills” (haksaenggun hullyǒn silsiryǒng sihaeng kyuch’ik), Defence Ministry Order No. 16/Education Ministry Order No. 29), that the appropriate amount of drill time for high school students was 156 hours per year, with 5 obligatory days in field camp.28

In exchange for participation in training rotines, the students – most of whom were at that point coming from better-off families – received draft deferments from the start of the conscription system in 1949.29 In wartime conditions, it was an enormous privilege, which meant that the scions of the propertied classes might be legitimately spared the horrors of the frontlines. It simultaneously underlined the inherently unfair nature of what was supposed to be “universal” conscription. The deferment system was scrapped in 1958, but students continued to enjoy an important privilege of serving only 18 months, that is half the usual term for conscripted non-students.30 The privileges the country’s would-be educated elite in discharging its military service obligations, were defended by the mainstream right-wing newspapers, Tonga Ilbo and Chosǒn Ilbo, on the grounds that higher education represented a crucial element of “national strength”, but was bitterly resented by many whose offspring were unlikely to share in them.31 In addition to legal privileges, illegal ones for the rich and well-connected presented another good reason for popular resentment. In the chaos of the war, and under Syngman Rhee’s corrupt and inefficient administration, the actual workings of the conscription system differed vastly from the orderly ideal of law- abiding citizens dutifully presenting themselves to recruiting agencies upon receiving their first official notice.32 Corruption was generally rampant in the military forces, especially on the issues of military recruitment.33 Lack of connection or inability to bribe one’s way out of the system could expose a conscripted youth to all sorts of abuse, including, for example, being forced to serve in the army twice.34 Many young people, lacking any trust in government and afraid of bad conditions and harsh treatment in the army, did everything possible to evade the draft. Even according to official statistics for 161,470 young males successfully drafted into the army between September 1955 and September 1956, there were 33,361 evaders,35 a situation that did not change significantly throughout the 1950s. In 1959, around 16% of the conscription-age males were dodging the draft – approximately the same share as in 1955 (16,8%).36 The state was perceived as externally imposed and predatory, the bureaucrats were considered self-interested rent-seekers, and the wide use of naked violence by the state reduced its perceived legitimacy. In such a situation, the conscription state sought by Syngman Rhee and his associates, could hardly succeed: conscription was, justifiably, seen as a “poor man’s draft”, which burdened the poorer disproportionably and was relatively easy to avoid for the sons of the rich and influential.

The situation began to change in the mid-1960s, however, as Pak Chǒnghǔi’s (Park Chung-hee) government, involved in the Vietnam War on the US side and aspiring to militarize the country to prevent the growing working class from becoming “restive”, simultaneously tightened implementation of the conscription laws and started a large-scale indoctrination campaign aimed at winning ideological hegemony for the “national defense state” the regime was building. Immediately after the junta led by Pak Chǒnghǔi assumed power on May 16, 1961, a national campaign against draft evasion was launched. The special “voluntary surrender periods” (chasu kigan), which allowed evaders to report to the authorities and simply perform their service with minimum or no punishment, were promulgated twice in 1961 and 1962.37 Already in early June 1961, 9,291 civil servants, including teachers, even in the private schools (customarily counted as “semi-civil servants” in Korea), were fired from their positions for failure to join the army at the appropriate time.38 The military manpower administration, previously a joint field of responsibility between the Interior Ministry (Naemubu) and the Defense Ministry, was from November 15, 1962, concentrated in the hands of the special Military Manpower Administration (Pyǒngmuch’ǒng), with regional bureaus in all provinces and bigger cities and 2010 specially trained employees nationally.39 The still-existing, although somewhat lenient, system of strictly controlling foreign travel by conscription-age males (under 35), which restricted permits for general traveling to 1 year, and for study to 4 years for undergraduates and 3 years for postgraduate study courses, with cancellation of passports after the expiration of the permit periods, was put in place on October 5, 1963 (Defense Ministry order No. 84).40 Foreign travel and study abroad were still largely elite pursuits in the 1960s, and the number of conscript-age males who were granted individual permits by the Defense Minister to travel abroad totaled 5,916 for all of the 1960s. Of them, 299 did not return, and their guarantors and families becoming objects of punishment.41 This aimed at strengthening the myth of “equality” in fulfilling military service and thus consolidated the ideological foundations of the new military regime.

Medical check-up of conscripts, 1970s

The strengthening the administrative machine, fear-provoking campaigns against both draft-evaders and their corrupt “abettors” in official positions, obligatory national identification cards from 1968 with fingerprints, stamped upon having completed military service,42 and other related measures drove down the rate of evasion from military service to a negligible 0.1% in 1974,43 thus giving people the view that military service as an inescapable part of a “normal” male lifecycle. They subjected to military drills from an early age: military training was re-introduced to the universities from 1968 and strengthened from December 1970.44 Starting in 1969, mandatory, basic military training (kyoryǒn) was also taught to both to male and female students (the latter focused upon emergency aid) in all high schools.45 It was praised as the way to make a “real man” (chincha sanai) on all levels of education, in mass culture, and in the media. Draft-evaders were made national scapegoats, accused of being both unpatriotic and unmanly, as manliness was now firmly identified with willing service in the army. This concentrated flow of militaristic propaganda, together with the strengthened popular legitimacy of the Pak Chǒnghǔi regime brought about by tangible economic success, seems to have won “ideological hegemony” of sorts for the conscription state. By the end of the 1970s, disgust at the “poor men’s draft” so widespread in the 1950s-60s, was largely replaced by acceptance, if somewhat grudgingly and unwillingly, of military service as an organic part of a “normal” male life and as natural as a citizen’s duty to pay taxes or complete primary and secondary education. Viewing military service as a matter of choice rather than an “innate” obligation of all Korean males towards “their” state and demanding a peaceful alternative to the draft was basically tantamount to questioning the legitimacy of the state and the fundamental coordinates of what was commonly viewed as “standard”, “normal” manhood. It comes as no surprise that, against the backdrop of such institutional and discursive settings, draft objectors became subjects of especially vigilant persecution.

South Korea may be classified as a “hardcore conscription state” –obligatory military service lasts 24 to 28 months at the time of this writing (last reduced in October 2003), is comparatively long by international standards. While Thailand, Columbia, or Kazakhstan also require their male citizens to serve approximately 2 years in the military, those EU countries that continuously practice conscription, rarely impose more than one year of compulsory service, and Taiwanese conscripts currently serve only 16 months. Practically all able-bodied Korean males aged 20-35, are legally required to serve. Korea’s standing army, staffed largely by conscripts at lower levels, has approximately 690.000 servicemen and servicewomen, while an additional 140,000 draftees serve for a longer period (28-32 months) doing civil tasks (public administration, work at “designated enterprises”, etc.), but only after having completed 4 weeks of basic military training. Thus, rather than being a genuine alternative service for those unwilling to take arms due to considerations of conscience, this “supplementary” service (poch’ungyǒk) presents a way of utilizing the “human material” judged, for reasons of health or any other reason (special qualifications, etc.) to be unfit for actual military duty. South Korea’s Military Duty Law does not envision the possibility of legally refusing to perform military service, and stipulates that those who object to active military service face prison sentences of up to three years (Article 88). Those who object to reserve force training, face prison sentences of up to six months or pay a fine of up to two millions wǒn (Article 90). In reality, however, the price those who either objected on principle to military service (COs – conscientious objectors) or simply tried to avoid it for a variety of personal reasons, had to pay, was much higher. First, there was (and there still is) the prospect of legal punishment, and in the 1970s, in the heyday of the Yusin (“revitalization”) dictatorship, it was not necessarily limited to 3 years. There were cases when COs, mostly Jehovah witnesses, were forcibly sent to the barracks even after completing their sentences, and then were given second ones, as they refused to serve once again; the process was often accompanied by cruel, sometimes lethal, beatings. The total number of imprisoned COs for the whole history of Korea after 1949 (when conscription was introduced) is more than ten thousand (more than 99% of whom are Jehovah witnesses), and over the last two decades there has been a constant increase: from 220 in 1992 to 683 in 2000, and 755 in 2004. The number is estimated by some Korean researchers to comprise around 90% of all COs imprisoned annually worldwide, in such conscription states lacking provisions for alternative service as Turkey, Korea, Azerbaijan or Angola. However, the customary sentence meted out to COs was shortened to 18 months by the early 2000s. It is the minimum time one has to spend in prison to avoid being drafted again. Second, there are institutional sanctions waiting for COs after their release from prisons – the criminal record prevents them from entering the service of the state or any major corporation, and effectively marginalizes them politically, socially and economically. Third, COs are still largely stigmatized by public opinion, often to the degree of making them “non-citizens” (pigungmin) in the eyes of the public. In such an atmosphere, which did not significantly change even after the “democratization” of 1987, closely knit religious communities like Jehovah witnesses were perhaps the only social groups able to withstand the enormous pressures and develop a CO movement. Although students belonging to undongkwǒn (anti-establishmentarian social movement circles) were often targeted in the army for indoctrination, forcibly recruited as informers or simply brutalized and killed in the 1980s, the undongkwǒn did not develop any recognizable CO movement in the 1980-90s. The only possible exception was the 1988 campaign against placement on the frontline (DMZ) by “NL” (“National Liberation” – left-nationalists) activists. The situation has only started to change in the 2000.46

Factors behind the emergence of the CO movement in the 2000s

The growth of the new CO movement in Korea in the 2000s was influenced by several factors. First, throughout the 1990s Korea’s undongkwǒn was undergoing a deep transformation. The beginning of this period was marked by the demise of the Eastern European Stalinist states, and 1995-1998 witnessed a major humanitarian catastrophe in North Korea. The transformation of European Stalinism into “normal” capitalism – together with capitalist restructuring by Mao’s successors in China – largely discredited those mainstream currents among the “PD” (“People’s Democracy” – orthodox socialists, often subscribing to various interpretations of Marxism-Leninism) followers which took Bolshevism in its Stalinist guise as their doctrine. The obvious inability of the North Korean state to secure its subjects the basic right to physical survival greatly reduced the appeal of pro-Pyongyang left-nationalists. However, the “anti- hegemonic” thrust of their propaganda retained a certain currency in the eyes of their followers, due to the continuous tension in the US-DPRK relationship and constant visibility of the US military presence in the southern part of the peninsula. Inside the undongkwǒn there emerged a tangible demand for rebuilding the ideological basis of activism, transcending both the “socialism in one country” dogma and rigid attachment to “anti-hegemonic nationalism” and its “liberated zone” in the North. The violent showdown between the police and nationalist-led Hanch’ongnyŏn students in August 1996, followed by a wave of arrests targeting almost exclusively left-nationalists, failed to deal a decisive blow to the “NL” stream of the student movement, but left it seriously weakened.47 The “PD” stream – including its moderate outgrowth called “21st Century Student Council” (21 segi haksaenghoe) – continued to control a sizable chunk of the universities – 27 in 1997 and 18 in 1998. They also applied new pressures to the hardcore nationalist leadership of Hanch’ongnyǒn,48 Lack of internal democracy and the need for reforming the entire movement were among the main issues on the agenda on March 3, 2001 meeting of Hanch’ongnyǒn’s Central Committee – the first such meeting in four years, since governmental repression relentlessly continued.49 On April 13, 2003, the reform-minded milder nationalists were at last elected into Hanch’ongnyǒn’s leadership, winning leading positions on a platform advocating internal democratic reforms and eventual legalization of the organization – which did not materialize in the end due to the unchanging governmental course.50

In this atmosphere of lively debates strongly tinged with a sense of crisis – as nationalistic rhetoric of “self-reliance” and “struggle for unification” appealed less and less to the student public, and Hanch’ongnyǒn’s visible lack of institutional democracy was becoming a major issue -interest in less orthodox means of “progressive struggle” was gradually growing. In the end, some of the former student radicals turned to the anti-military movement, perceiving it as a venue for fulfilling the aspirations which grew out of the old “NL” and “PD” platforms but not realizable inside the framework of the older 1990s student movement. For example, Yu Hogǔn (born 1976), who proclaimed his refusal to serve in the army on July 9, 2002 – thus being among the pioneering non-Jehovah witness COs in Korea – belonged to a left-nationalist stream in the Korean Democratic Labour Party (KDLP).51 He proclaimed himself a CO saying that he would never point his gun at another Korean, regardless of the state affiliation forced upon them by the era of national division; but at the same time advocated a “pluralistic society”, which would acknowledge the differences between those who agree to serve in the army and those who do not.52 His example vividly shows the changes in worldview of some milder left-nationalists brought about by the crisis and uncertainty of the 1990s undongkwǒn milieu. A good example of a “PD” activist-turned-CO is Na Tonghyǒk (born 1977).53 He declared himself a CO on September 12, 2002, and, explaining his decision, mentioned, among other things, Korea’s “defensive, exclusionist nationalism, typical for a country which has been through a war, but also useful for controlling and freezing a society in the name of national security, locking up people’s imagination and making it comfortable and natural for people to be controlled in their everyday lives”.54 In this case, the “PD” aversion to nationalism, which deepened in the course of the competition with hardcore mainstream “NL” forces for influence on campuses, further developed into a logic of struggle against the logic of the “national security state” underpinned by nationalism.55 The fact that the representatives of two competing anti-establishmentarian ideologies, “PD” and “NL”, eventually became comrades in the anti-militarist struggle may seem somewhat paradoxical, but it shows that the introduction of the anti-militaristic topic was necessitated by the general logic of the development of Korea’s social movement in the 1990s. This logic expanded confrontation with the state to deeper layers of Korea’s “life world”, and challenged the “national security complex” underlying the whole construction of Korea’s dominant ideology.

The second factor which definitely influenced the growth of the CO movement in the 2000s, was a general strengthening of the left-wing in Korean politics in the wake of several landmark events – the first-ever pan-national general strike after 1946 and a concomitant wave of demonstrations and mass meetings by radical labour unions in December 1996-February 1997, the Asian financial crisis and the IMF bailout in late 1997-early 1998, and Kim Taejung’s (Kim Dae- jung) government rise to power in February 1998. While the general strike, with the participation of around 380,000 unionized workers,56 demonstrated the mobilization potential of anti-establishmentarian radicalism, the fact that Kim Taejung’s government, initially supported – albeit “critically” – by many activists, especially among left-nationalists, rushed to implement the IMF restructuring programme which undermined the livelihoods of a large part of the working class, distinctively showing the need for political organization by the workers and for the workers, and alienating activists from mainstream “bourgeois” politics. KDLP, formed on January 30, 2000, by moderate “PD” activists on an anti-neoliberal, “welfarist”, and pro-peace platform,57 instantly became a popular alternative for unionized workers, lower-ranked intellectuals and a large segment of the lower middle and middle classes. In an opinion poll conducted around the time of its formation, it was ranked 3rd by its approval rating, which was 20.9%.58 The unexpectedly high approval rating did not immediately translate into electoral success, but in the December 2002 presidential elections the KDLP candidate, Kwǒn Yǒnggil, scored 3.98%, having almost one million Koreans vote for him, and during the April 2004 parliamentary elections, the party elected 10 MPs and managed to get 13.1% of the vote.59 Given the scale of anti-communist indoctrination in Korean society up to the mid-1990s, the achievements of the KDLP were indeed unusual, reflecting the deep sense of frustration in non-privileged sectors of the society over all mainstream politics. The very fact that a legal workers’ party existed that highlighted “peace” in its programme and advocated reduction of both North and South Korean armies to the 100,000 level, and abolishment of conscription in South Korea and introduction of a professional military,60 was an enormous psychological boost for the fledgling CO movement. A sizable portion of COs in the 2000s are KDLP members – O T’aeyang (the first to declare his refusal to serve, on December 17, 2001), Yu Hogǔn, Kim Yǒngjin (Dongguk University philosophy student, declared himself a CO on January 1, 2005, currently imprisoned), and several others. However, so far organizational support of the KDLP for the CO movement has been very limited.

O T’aeyang

The third factor is a massive gap between the state of Korea’s civilian society and life in the barracks. That compulsory military service in Korea often entails direct danger for one’s life is indicated by the large number of cases under investigation by the governmental Investigation Committee on Suspicious Deaths in the Army (Kun ǔimunsa chinsang kyumyǒng wiwǒnhoe, formed in January 2006). By the beginning of January 2007, the number of cases accepted by the Committee had reached 595.61 Even during the supposedly “democratic” 1995-2005 decade, the average annual number of deaths in the army was 202, and 41% of this number were officially declared “suicides”. It is quite obvious, however, that in many cases the “suicides” were, in fact, violent deaths caused by “disciplinary” beatings by superiors; in other cases, there are ample grounds to suggest that the conscripts in question were driven to suicide by the institutionalized brutality of barrack life.62 In fact, already by the end of 2006, the Investigation Committee managed to confirm that in two of the cases it had accepted – one of them as recent as 1996 – the deaths, initially classified as “simple death” (tansun samang) or “suicide”, were, in fact, caused by beatings.63 While “disciplinary” killings look somewhat extreme and unusual even by the standards of the Korean army, “simple” beatings, together with other forms of abuse (verbal, sexual, etc.) remained a “normal” part of military life until very recently.64 It looks as if certain efforts to eradicate at least the worst forms of abuse in the barracks and make military life more acceptable for conscripts occurred in the last fewyears.65

Nevertheless, prospective conscripts still have ample reasons to view military life as intolerable, inhumane oppression aimed at dehumanizing young males and instilling the habits of blind obedience. A survey of writings and statements by Korean COs shows that extreme aversion towards routine brutalization of conscripts played an important role in forming their general attitudes towards military service. The role of the CO movement in the improvement of the “feudal authoritarianism” of army life, its potential to strengthen the pressure upon the military authorities to eradicate the practice of physical punishment in the barracks, were highlighted, for example, by an anonymous activist in the CO movement in a letter sent to the Korean Socialist Party (Han’guk sahoedang) on May 16, 2003.66 In addition to physical violence, another unsavory part of military life for urban conscripts who lean towards independent, progressive thinking is “moral education” (chǒngsin kyoyuk) – a weekly four hour long (two hours for technical units) weekly indoctrination sessions.67 The thaw in inter-Korean ties in the early 2000s led to a significant weakening of anti-North Korean army rhetoric (for example, by the end of 2004, South Korea’s White Book on Defence stopped defining North Korea as the “main enemy”).68 While it is possible to surmise that such a change at the top influenced indoctrination below, it still basically clings to the Cold War worldview, emphasizing the “reality of the hostility” between North and South over peace ideals or possible unification.69 Since the military is quite slow to reform its ways of “educating”, disciplining and punishing conscripts, army brutality is expected to stimulate the anti-military movement for a long time to come.

Everyday brutality – a conscript being punished by a senior soldier in the Korean Army

Last but not least, intensification of worldwide warfare by the US and its allies in the early 2000s, together with mounting tensions on the Korean Peninsula after the inauguration of the G.W. Bush administration in January 2001, seemed to greatly boost the pacifist strain in Korea’s social movement camp, inspiring COs for a struggle not only against their own country’s militarism, but also against the phenomenon of militarism as such. Individual COs and their organization, “World without war” (withoutwar.org: Chǒnjaeng ǒmnǔn sesang), formed on May 15, 2003, were active participants in the campaign against Korean participation in the US-led invasion of Iraq. One of Korea’s best-known COs was actually an active-duty soldier, Private 2nd class Kang Ch’ǒlmin, who proclaimed himself a CO while on leave in November 2003, protesting Korean government plans to send Korean troops to Iraq. He was given the 18 month-long sentence customarily meted out to COs, and released on parole from custody in February 2005.70 Another cause célèbre for Korea’s pacifists was the struggle against the forcible removal of villagers in Taech’uri and Toduri near P’yǒngt’aek, when the government decided to confiscate 2,851 acres of their land to expand Camp Humphreys of the United States Force Korea (USFK). The campaign, which lasted more than a year, culminated on May 5, 2006 in a violent eviction of resisting farmers and activists by around 13,000 Korean army troops.71 Several COs were among the Taech’uri defenders on May 5, 2006, and “World Without War” issued a strongly worded protest against military and police violence in the P’yǒngt’aek area, pointing out that the modern Korean state monopolized the legal means of violence, but still continued to behave in a manner more befitting an organized criminal group.72 The Korean government kept its 2,300-strong military contingent in northern Iraq for several years, and did not complete their withdrawal until December 2008.73 It also contributed 360 soldiers to the “peacekeeping mission” in Lebanon, which promises to be anything but peaceful.74 It is quite clear that Korean participation in US wars or in missions related to conflicts initiated by US allies will continue to fuel anti-militarist protest inside Korea’s social movement.

Composition of the 2000s CO movement

The jumpstart for the CO movement in the 2000s was provided by O T’aeyang’s public refusal to serve in the military (December 17, 2001). O, born in 1975 in Kwangju, was early traumatized by the soldiers’ violence he experienced during the 1980 Kwangju massacre, and by the ubiquity of violence in Korea’s family and social life. A graduate of Seoul Pedagogical University, he became a deeply devout Buddhist and simultaneously led the life of a social activist, working full-time for a Buddhist humanitarian organization “Good Friends” (Choǔn pǒt dǔl).75 His decision to refuse serving in the military partly had its background in O T’aeyang’s involvement in social activism, but was mostly based on his Buddhist beliefs – which included the disciplinary precept against taking life, and on the belief that violence could never lead to peace.76 However, despite the tangible depth of O T’aeyang’s Buddhist beliefs, his CO declaration received only very limited and guarded support from his co-religionists. Institutional Buddhism, represented in Korea by the Chogye Order and many lesser Buddhist denominations, provided no public support at all: the Chogye Order never made any official statement on the issue, while its representative inside the military, Kim Marhwan, the Buddhist director of the Army’s Religion Office (Kunjongsil), told reporters in June, 2004, that Korea’s Buddhism is “state- protecting in character” and “takes military service as a form of realizing the Bodhisattva’s way, by sacrificing yourself for the sake of the others”.77 A spiritual head of another main Buddhist denomination, the T’aego Order, the Chongjǒng Hyech’o,, interpreted in a private capacity, Buddhism’s attitude towards military service in an even more original way, saying that serving in the army in peacetime does not involve any killing and thus does not contradict Buddhist precepts; moreover, only after having fulfilled one’s obligations to the state can one rightly serve Buddha.78 However, by February, 2002, O T’aeyang received messages of encouragement and support from a number of lay Buddhist organizations,79 and also very active assistance from some influential monks involved in social causes.80 The fact that O T’aeyang’s views were also widely aired, mostly in a very positive light, by a variety of progressive media outlets, including Hangyǒre and www.ohmynews.com , and made into a national issue by human rights campaigners, undoubtedly contributed to producing a small miracle in the world of Korean jurisprudence – in February 2002, O T’aeyang was released for the duration of his trial on charges of violating the conscription law, to be sentenced and imprisoned only in August 2004, and then released in November 2005.81 His two years of unexpected freedom in 2002-2004 turned out to be an enormous boost for the CO cause, as his activities (interviews, lectures, and articles) hugely contributed to exposing the whole conscription system and popularizing anti-militarist beliefs.

Buddhist chaplains (kunsǔng) in the Korean Army, wearing military uniforms, symbolize the collusive ties between institutional Buddhism and the military

O T’aeyang’s pioneering declaration and the momentous controversy it created, were followed by successive “coming-outs” of other COs. The non-Jehovah witnesses who declared their refusal to undergo military training in the 2000s – numbering around 30 in 2001-2007 – may be categorized in the following way:

a) Socialist/left-nationalist activists. Together with Na Tonghyǒk and Yu Hogǔn, mentioned above, several other people belong to this category, notably Yǒm Ch’anggǔn (born in 1976, declared himself a CO on November 13, 2003), who served as a managing director (samu kukchang) for Iraq Peace Network, the umbrella organization for a variety of groups involved in the struggle against Korean participation in the US invasion of Iraq. Yǒm aspired to go to Iraq as a “living shield” in early 2003, but his intentions were thwarted by regulations that severely limited the right of conscription-aged males to leave the country.82 So far, the number of Korean socialist COs is very small in proportion to the size of the socialist milieu. This is due both to family pressures and the several limitations a criminal conviction for refusal to serve may impose on one’s professional life and political career. However, the belief in the basic right to refuse military service to a (capitalist) state seems to have become an accepted article of faith among Korea’s political radicals, excluding perhaps only hardcore pro-Pyongyang left-nationalists.

b) Religious COs – for the time being, two Buddhists (O T’aeyang and Kim Tohyǒng; the latter, born in 1979, proclaimed himself a CO on April 30, 2004, and received an 18-month sentence), one Catholic (Ko Tongju, born 1980, proclaimed himself a CO on October 19, 2005), and one Protestant (Kyǒngsu, born in 1980, proclaimed his refusal to serve in June 2006). A common feature of nearly all of them is activist participation in religious youth groups: Kim Tohyǒng had worked full-time for the Korean Students’ Buddhist Federation (Han’guk taehaksaeng pulgyo yǒnhaphoe), while Ko Tongju, born to a deeply Catholic Cheju family, rose to vice-chairmanship of the Seoul Diocese Federation of Catholic Students (K’at’ollik taehaksaeng yǒnhaphoe). Young activists holding broadly progressive orientations, especially in Catholic and Buddhist communities, tend to be either sympathetic or, at least understanding of “their” COs – fellow religious activists, whose devotion to their respective faiths is well-known in their denominations. The attitude of the denominations to which the religious COs belong is, however, much more guarded. It has already been mentioned above that the main Buddhist denominations in Korea have never made any clear public statements on the issue of military objection, obviously either being unable to give a full, logical and non-contradictory doctrinal justification to the fact of their long-established collaboration with the Korean military, or being unwilling to expose their pro-military attitudes to the progressive- minded younger Buddhist public. In private interviews, however, they emphasized the primacy of the obligations of a Korean Buddhist (kungmin ǔrosǒǔi pulcha) towards the state and the link between sacrifices in the name of the state and the realization of Buddhist ideals. Catholics used to show much more awareness of worldwide trends in religious pacifism and Biblical doctrinal justifications for the refusal to undergo military training: Cardinal Kim Suhwan told Educational Broadcasting (Kyoyuk pangsong) in one interview in March 2002, that alternative service for the COs is acceptable in principle, as long as it does not threaten the state’s defense potential.83 Clearly this statement was influenced by Cardinal Kim’s knowledge of the authoritative “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et Spes” adopted by the Second Vatican Council in 1965 and including the following clause about conscientious objection: “It seems right that laws make humane provisions for the case of those who for reasons of conscience refuse to bear arms, provided however, that they agree to serve the human community in some other way”.84 However, despite the ultimate acceptance of the conscientious refusal to bear arms by the Vatican in 1965, the Korean Catholic hierarchy still avoided giving any official and public encouragement to Korea’s own potential Catholic COs, obviously unwilling to challenge the prevailing militaristic norms of the society and disturb its own cooperative relationship with the military.85 Thus, the Korean Catholic hierarchy practically reaffirms its conservative vision of a confrontation with North Korea as a “just war”.86 In this context, it should be remembered that, unlike many Catholic leaders worldwide, in November 2003, Cardinal Kim Suhwan supported the dispatch of Korean troops to Iraq “for the sake of peace and reconstruction” – while at the same time reiterating the Vatican’s basic position critical of the Iraq war itself.87 While Buddhists and Catholics largely avoid public debates on the issue of the conscious objection, Protestants seem to be sharply divided. While the progressive Korean National Council of Churches (KNCC: Han’guk kidokkyo kyohoe hyǒbǔihoe) officially urged the government in May 2004 to speedily introduce an alternative service for pacifists and to stop imprisoning them, the conservative Christian Council of Korea (CCK: Han’guk kidokkyo ch’ong yǒnhaphoe) stated that the introduction of alternative service might only “disrupt public harmony and endanger our national security”.88 Even progressive Protestant clergymen, however, kept relatively low profiles in the debates on conscientious objection and alternative service, avoiding doing anything that may compromise their credentials as assiduous contributors to the “national defense” cause in the eyes of more conservative audiences.

c) Environmentalists and followers of alternative lifestyles – a growing category of objectors, which includes, for example, environmental activist Ch’oe Chunho and environmentally minded primary school teacher Ch’oe Chin89, or gay activist Im T’aehun.90 The common motive for this group of military objectors, together with their reluctance to be trained as killers of living beings, is the rejection of the authoritarian nature of military life – that is, extreme unwillingness to accept the uniformity and absolute obedience that barrack life imposes. Possibly, the clearest expressions of such sentiments are the interviews and writings by one of the most unconventional representatives of “alternative Korea”, anarchist Cho Yakkol.91 Radical anarchists are a tiny minority inside the Korean social movement, and have a much smaller following than other radical non-conformist groups – Trotskyites (International Socialists), militant “PD” groups, or hardcore left-nationalists. However, the environmental movement is known to be on the rise, and coming-out becomes easier and easier for sexual and lifestyle minorities. It may be expected that activists from these milieux will continue to fill the ranks of COs, motivated both by their belief in non-violence and by their alienation from the Korean state, with its persistent developmental agenda, consistent disregard for environmental concerns, and continuous use of “disciplinary” techniques in the educational sphere and barrack life.

As demonstrated above, the CO movement of this century includes widely diverse components: radical socialists (Yi Wǒnp’yo) have, for example, a political and social outlook essentially different from that of minority activists (Im T’aehun). But what is interesting is the degree of “cross-involvement” inside the CO movement: some religious COs, especially Kim Tohyǒng, are active in the environmental causes, others –for example, O T’aeyang – became KDLP members and tried hard to achieve their (moderate) socialist ideals and religious beliefs. Practically all the COs, united under the umbrella of their main organization, “World Without War”, were very prominent in the campaigns against the deployment of Korean troops to Iraq and against the forcible removal of the Taech’uri and Toduri peasants. In a way, CO/anti-military movement seems to become a “cooperation zone” within the social activism domain in Korea’s public life – a zone, where cross-fertilization between diverse and often conflicting branches of Korea’s social movement is possible. The struggle against the conscription state emerges today as a common denominator for Korea’s assorted and heterogeneous social movement community, together with a number of other foreign policy and domestic issues (disengagement from Iraq, boycott of Chosǒn Ilbo, etc.). But while in the matter of military service, the right to choice seems to have been firmly adapted as a part of the unwritten commonsensical credo of Korea’s progressive circles, it still has not become a part of wider popular consciousness.

Anti-military activist, Kang Ǔisǒk (Seoul National Univeristy, Faculty of Law student), fully naked, protests a military parade in Seoul in 2008.

CO movement – a long road to official and popular recognition?

While the concrete, short-term aim of the CO movement is defined as the introduction of an alternative civil service for draftees with pacifist beliefs, the long-term, broader aim is to scrutinize the “militarized citizenship” complex and the whole framework of the “national security state” ideology, as well as legitimize non-violence as the new, alternative norm for societal and personal behavior.92 However, despite greatly strengthened awareness of pacifism inside the social activists community, both aims of the CO movement have thus far only been achieved to a very limited degree. The road to recognition of pacifist beliefs both on the legal level and in popular consciousness still seems to be a long way off.

On January 29, 2002, a judge from the Southern Seoul District Court, Pak Sihwan, who had to sentence a Jehovah witness refusing to take arms, sent an appeal to the Constitutional Court (Hǒnpǒp chaep’anso) alleging that Korea’s Military Duty Law (Pyǒngyǒkpǒp), which does not provide any venue for realization of pacifist beliefs, is anti-constitutional.93 As the matter was under investigation at the Supreme Court (Taebǒbwǒn) and Constitutional Court, a number of pioneering non-Jehovah witness COs were paroled. This gave wide publicity to the issue and gave the COs an opportunity to promote their cause in the media while waiting court decisions. However, this pause in the legal persecution of COs – possibly influenced, among other factors, by a “détente” mood on the Peninsula after the June 2000 summit meeting between North and South Korean leaders – did not last long. Although in May 2004 another Southern Seoul District Court judge, Yi Chǒngnyǒl, gave, for the first time in modern Korean history(!), an acquittal to three Jehovah witnesses refusing the join the army,94 this historical verdict was soon overturned by two successive decisions of the Supreme Court and Constitutional Court. It ruled, in July and August 2004 respectively, that the COs were to be found guilty of violation of the Military Duty Law, and that the Military Duty Law in its existing form is fully constitutional. The ruling of the Constitutional Court (voted 7:2), stated significantly that the future introduction of an alternative service would require a “national consensus” (kungminjǒk konggamdae). This was obviously judged to be lacking for the time being – and the state had to investigate ways to accommodate the demands of the COs – but at the same time was not constitutionally prevented from punishing them at present.95 The ruling – which came as Korea was preparing for its September 22, 2004, deployment of 2,800 troops to Iraq,96 despite the staunch opposition of a majority of influential NGOs and amidst a growing alienation between progressive NGOs and Pres. No Muhyǒn’s regime – signaled that repression against COs was back to “normal”. Pre-trial detentions of COs once again became common, although the practice of giving COs “custom-tailored” 18-months sentences – a minimal sentence for making an individual exempt from conscription in the future – established in 2000-2001, did not change, and most COs actually continued to be paroled after having served about a year. The conservative court’s onslaught on CO rights was to a certain degree reversed when the National Human Rights Committee (Kukka in’kwǒn wiwǒnhoe) recommended on December 26, 2005 that the right of conscientious objection to military service be officially acknowledged, and alternative service introduced.97 Influenced by this decision, the defense minister promised on February 9, 2006, that a decision on the introduction of alternative service would be made after approximately one year of thorough deliberation98

It should be remembered, however, that neither the “recommendations” of the National Human Rights Committee nor any “promises” by the defense minister were binding. Indeed, while the Defence Ministry promised in September 2007, in the last days of Pres. No Muhyǒn’s administration, to draft and submit to the Parliament a new law allowing alternative service for the religious COs,99 subsequent political changes cast doubt on its willingness to do so. After the new conservative administration of Pres. Yi Myǒngbak assumed power in early 2008, the Defence Ministry announced that it would “further look into public opinion” and “thoroughly reconsider” its previously stated commitment to establish the alternative service option, hinting that it might renege on its promises. Eventually, on December 24, 2008, it declared that “lack of national consensus” did not presently allow the government to implement alternative service, while leaving open this possibility in the future.100 The external pressure – the fact that the right to conscientious objection is recognized by the UN Commission for Human Rights as one of the basic civil and political rights,101 the UN Commission for Human Rights in early December 2006 recommended that the South Korean government compensate previously imprisoned COs and stop imprisoning COs,102 and that the issue of Korea’s CO rights started to attract the attention of many human rights groups all around the world – does not seem to have decisively affected the course of the South Korean authorities. Far more decisive is the ability of the defence establishment and its allies in the media and educational system to continuously inculcate the notion of the “sacredness” and “indispensability” of the conscription system into the minds of the public, and to present COs as “deviants” – “religious fanatics” (in the case of the Jehovah witnesses), “immoral individuals”, “ideologically impure persons”, etc. So far, it appears that the ideological hegemony of the “national security state” remains solid, despite all the challenges put forward by the CO movement and the NGOs supportive of it in the last years.

While the last six to seven years saw publishing of several masterfully written books by legal experts, gender researchers and civil activists on the issue of militarism, conscription and CO rights,103 and several popular media publications, prominently the Daily Hangyǒre and the Weekly Hangyǒre21, took a consistent and principled stand in favour of the introduction of an alternative service system, the majority of the conservative media refused to prioritize human rights over the “sacred” issue of “national security”. Some strongly-worded editorials warned of the “grave danger of the growing mood of refusal of military service”,104 while others expressed doubts as to whether the National Human Rights Committee, which “came to the extreme of taking the side of military objectors” should exist at all.105 Most important, TV broadcasting, with its high penetration rate and ability to manufacture “popular consent”, continued to cover CO-related issues only sparsely and mostly focusing on the potential “negative influence” of military objection on “national defense”.106 The schools, for their part, continue to teach in civics classes that military service is the “sacred duty” of Korean males, indispensable for proving one’s masculinity and Koreanness.Teachers who refuse to toe the line, are still being punished.107 Little wonder that, in the situation when the KDLP’s progressive political agenda still remains largely marginalized in public political debates, the carefully crafted media and educational indoctrination strategy of the defense establishment and its allies brings these results: according to 2005 opinion polls (commissioned by the Defense Ministry), only 23.3% of the polled were in favour of introducing alternative service, although, significantly enough, the idea was favoured by 36.6% of the conscription age youth.108

Even if Korea’s Defense Ministry were to introduce an alternative system in the (distant) future, it would likely be limited to religious COs, thus leaving the tiny minority of socialists, environmentalists and non-religious pacifists to be punished and excluded from mainstream society – as a criminal record bars employment by the state, and scares many larger private employers. Judging from the way popular opinion is being formed today by newspaper and TV coverage, it is highly likely that alternative service would be punitive in character, for example, longer than the “normal” military service. Given the present state of regional tension in North-East Asia, as well as the ideological hegemony of the “national security” establishment, it is also highly likely that such a course will not meet mass popular resistance. However, that does not mean that the CO movement of the 2000s has achieved nothing. If the ideological hegemony of the hardcore conscription state is by and large intact, its ideological monopoly is gone forever: the subject of the anti-militarist movement, once taboo, is now firmly within the domain of public debate, and it continues to challenge orthodox views on both citizenship and “normative” masculinity. Appearing in the progressive media, the COs, who voluntarily choose imprisonment and potential exclusion from mainstream careers even after their release, present an image of self-sacrificing conviction, in sync with the traditional Confucian view of fidelity to one’s beliefs and perseverance in adversity. At the same time they staunchly refuse to allow the state to discipline their minds and bodies in the barracks, thus showing by their example that joining the army is not the only way to become a “real man”. The very fact that conscientious objection and the introducing an alternative service are being mentioned as “matters for deliberation” by the governmental, itself may help to destroy the myth of the “sacredness” of military duty: if it were truly sacral, the first people of the state hardy could have been allowed to commit “blasphemy” by mentioning alternatives. The challenge the CO movement presents to the state-approved image of the “model” male citizen voluntarily submitting to army discipline, passes the limits of debates on conscription and conscientious objection. If military service to the state is a matter of choice with individual conscience being the central criterion, then the same may be inferred about the whole spectrum of relationships between the individual and the powerful institutional actors of social life. Once state-sponsored militarism can be rejected by an act of individual conscience, the same may apply to the developmentalist logic that makes sacred the likes of Samsung Electronics into the “cornerstones of national economy” and precluding any consistent, thorough criticism of their managerial, environmental or labour practices, especially abroad, where they “earn foreign currency for the motherland”. It also challenges repressive labour immigration policies presented under the banner of “national interest”, which practically rules out legal immigration of mostly Asian and African manual workers to Korea for prolonged periods of time, with no hope of lawful permanent settlement. In brief, the challenge to the “sanctity” of conscription is, by implication, a major challenge to the whole set of officially-sponsored beliefs and values, which may be defined as Korea’s “establishmentarian ideology”. If this challenge is continuously pursued with today’s intensity, we may expect that it will further undermine the beliefs imposed by ruling groups, and could eventually contribute to a major re-definition of the dominant ideology.

Born in Leningrad (St-Petersburg) in the former USSR (1973) and educated at St-Petersburg State University (MA:1994) and Moscow State University (Ph.D. in ancient Korean history, 1996). Vladimir Tikhonov (Korean name – Pak Noja) is a professor at Oslo University. A specialist in the history of ideas in early modern Korea, he is the author of Usǔng yǒlp’ae ǔi sinhwa (The Myth of the Survival of the Fittest, 2005. He is the translator (with O.Miller) of Selected Writings of Han Yongun: From Social Darwinism to Socialism With a Buddhist Face (Global Oriental/University of Hawaii Press, 2008). This is a revised and updated version of his contribution to the collection entitled Contemporary South Korean Capitalism: Its Working and Challenges, (forthcoming, fall 2009, Oslo Academic Press).

Posted at The Asia-Pacific Journal on March 16, 2009.

Recommended citation: Vladimir Tikhonov, “Militarism and Anti-militarism in South Korea: ‘Militarized Masculinity’ and the Conscientious Objector Movement,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12-1-09, March 16, 2009.

Sources

An Honguk, “’Kangnyǒng minjujǒk hǒnhwan’ hubo ǔijang tangsǒn. Hanch’ongnyǒn happǒphwa t’allyǒk padǔl dǔt” (The candidate who pledged to democratize the Hanch’ongnyǒn platform wins. The legalization of Hanch’ongnyǒn may get momentum), – Kyǒnghyang sinmun, April 14, 2003

“Assembly panel OKs Lebanon troop dispatch”, – Korea Herald, December 16, 2006.

Aussaidǒ ǔi mal (Words by the Outsiders), Seoul: Aussaidǒ, 2004

Richard Benson, “The ‘Just War’ Theory: a Traditional Catholic Moral View”, – The Tidings, January 10, 2007:

Ch’ae Sǒngju, “Yusin ch’eje ha ǔi kodǔng kyoyuk kaehyǒk e kwanhan yǒn’gu” (Research on the Higher Education reform under the Yusin System), – Kyoyuk haengjǒnghak yǒn’gu, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2003, pp. 317-336.

“Chingjip chingbyǒng pujǒng tǔrǒ ǒje kukhoe esǒ taejǒngbu chilmunjǒn chǒn’gae” (The “war of questions” to the government yesterday in parliament about the corruption around conscription into the army), – Tonga Ilbo, October 26, 1952.

Cho P’ungyǒn et al, “Chonggyo iyu pyǒngyǒk kǒbu ch’ǒt muchoe” (The first-ever acquittal of religious COs), – Daily Segye Ilbo, May 21, 2004.

Ch’oe Chǒngmin, “Sahoe Pongmuje, kukhoe e nǒmgyǒjin kong” (Alternative service: the ball sent to Parliament), – Pressian, November 21, 2007.

Chǒng Hosǒn, “Sǒuldae ch’onghaksaeng hoejang sǒn’gǒ piundongkwǒn sasang ch’ǒǔm ch’oeda tǔkp’o” (For the first time in history, a non-undongkwǒn candidates receives the majority of votes in the election of Seoul national University student council chairman), – Daily Maeil Kyǒngje, November 24, 1999

Chǒng Inmi, “Zaitun pudae p’abyǒng yǒnjang tongǔian kukpangwi t’ongkwa” (The motion to prolong the dispatch period for the Zaitun unit [in Iraq] passed by [National Assembly’s] Defence Committee), – Minjung ǔi sori, December 12, 2006

Chǒng Kyǒngt’aek, “Chumin tǔngnokpǒp sihaengnyǒng kaejǒng naeyong kwa kǔ ǒmmu ch’ǒri” (The Revised Implementation Regulations for the Residents’ Registration Law and Processing of Related Administrative Duties), – Chibang Haengjǒng, Vol. 18, No. 189, 1969, pp. 141-144.

Sandi E. Cooper, “Pacifism in France, 1889-1914: International Peace as a Human Right”, – French Historical Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2, Autumn, 1991, pp. 359-386.

Uri Ben-Eliezer, “A Nation-In-Arms: State, Nation, and Militarism in Israel’s First Years”, – Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 37, No. 2, April 1995, pp. 264-285.

Cynthia Enloe, Morning after: Sexual Politics at the End of the Cold War, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993

Samuel Finer, “State and Nation-Building in Europe: The Role of the Military”, – Charles Tilly (ed.), The Formation of National States in Western Europe, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975, pp. 84-163.

Robert Gilpin, “The Theory of Hegemonic War”, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 18, No. 4, Spring 1988, pp. 591-613.

“Haksaeng kwa hakpumo pohoharyǒ haetta” (We were going to protect the pupils and their parents), Weekly Hangyǒre 21, August 17, 2006

Hong Sehwa, “Yangsimjǒk pyǒngyǒk kǒbu wa taech’e pongmu” (The COs and alternative service), Daily Hangyoreh, June 22, 2004

“Hǒnjae, ‘kukpobǒp, pyǒngyǒkpǒp haphǒn kyǒlchǒng’” (The Constitutional Court rules that the National Security Law and Military Duty Law are constitutional), KBS TV, August 26, 2004

Im Ch’anggǒn, “Nyusǔ haesǒl: “yangsimjǒk pyǒngyǒk kǒbu wa anbo ǔi chǒpchǒm” (Comments on the news: the point of contact between “conscientious objection” and “national defence”) , KBS, December 29, 2005

Im Hyǒnjin, “Han’guk ǔi sahoe undong kwa chinbo chǒngdang kǒnsǒl e kwanhan yǒn’gu” (A Study of Social Movements and Progressive Parties in Korea), Han’guk sahoe kwahak, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2001, pp. 1-49.

Im Myǒngsǒp, “Chǒn, ǔigyǒng 41% kahok haengwi kyǒnghǒm, irǒlsu ga” (41% of the draftees in the militarized police and the conscript-staffed police units experience brutalities – is it possible?), Bǔreik’ǔ nyusǔ, November 14, 2005

Kang Sinuk, “97 nyǒn ihu 4nyǒn man e sǒngsatoen Hanch’ongnyǒn chungang wiwǒnhoe” (Hanch’ongnyǒn’s Central Committee meeting – for the first time in 4 years, since 1997), Minjung ǔi sori, March 6, 2001

Kang Sǒhǔi, “Pyǒngyǒk kǒbuja Yǒm Ch’anggǔn, Yi Wǒnp’yo ch’ulso” (COs Yǒm Ch’anggǔn and Yi Wǒnp’yo came out from prison), January 31, 2006

Kim Chaejung, “Yangsimjǒk pyǒngyǒk kǒby ch’ǒbǒl pǒbwǒnesǒ wihǒn simp’an chech’ǒng” (A court appeals to investigate the [possible] anti-constitutionality of punishing COs), Daily Kungmin Ilbo, January 30, 2002

Kim Ch’angsǒk, “Hanch’ongnyǒn, tasi pyǒnhyǒk ǔi kippal ǔl ollinda” (Hanch’ongnyǒn again raises the banner of reforms”, Weekly Hangyore21, Issue 152, April 10, 1997

Kim Hayǒng, “’P’abyǒng pandae yangsim sǒnǒn’ Kang Ch’ǒlmin ibyǒng kasǒkpangtwae” (Private 2nd class Kang Ch’ǒlmin, who issued a declaration of conscience protesting against the dispatch of [Korean] troops [to Iraq] released on parole from prison), P’ǔresian, February 28, 2005

Kim Samsǒk, Pan’gapta, kundaeya! (Glad to See You, Army!), Seoul: Sallimt’ǒ, 2001

Kim Tonghun, “Hanch’ongnyǒn kaehyǒk e han moksori” (All demand the reform of the Hanch’ongnyǒn), Monthly Sindonga, January 1997

Kim Tusik, K’al ǔl ch’yǒsǒ posǔb ǔl (Swords to Ploughshares), Seoul: Nyusǔ aen choi, 2002

Kim Yǒnggon, Han’guk nodongsa wa mirae (Korean Labour History and Future), Seoul: Sǒnin, 2005, Vol. 1-3

Kim Yongjun, Nae ga pon Ham Sǒkhǒn (Ham Sǒkhǒn as I saw him), Seoul: Ak’anet, 2006

“Kukka podan kaein ǔi inkwǒn I tǒ sojung” (Individual human rights are more important than the state), Daily Hangyǒre, June 28, 2002

Kwǒn Insuk, Taehan Min’guk ǔn kundae da (The Republic of Korea is an army), Seoul: Ch’ǒngnyǒnsa, 2005

“’Kyoryǒn’ yǒksa sok ǔro. 38 nyǒn man e kaemyǒng” (“Basic Military Training” Becomes History – renamed after 38 Years), Yǒnhap nyusǔ, January 28, 2007.

Ronald Lawson, “Church and State at Home and Abroad: The Evolution of Seventh-day Adventist Relations with Governments”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, LXIV/2, 1996, pp. 279-311.

“Lebanon Tongmyǒng pudae 2chin p’abyǒngsik” (The ceremony of the dispatch of the second part of Tongmyǒng Unit to Lebanon), Yǒnhap nyusǔ, January 15, 2008

Yagil Levy, “Militarizing Inequality: A Conceptual Framework”, Theory and Society, Vol. 27, No. 6, December 1998, pp. 873-904.

O Cheyǒn, “1950nyǒndae taehaksaeng chiptan ǔi chǒngch’ijǒk sǒngjang” (Political Growth of Students as a Social Group in the 1950s), Yǒksa Munje Yǒn’gu (Research on Historical Problems), Vol. 19, 2008, p.p. 180-181.

Pak Sǒngjin, Kim Yujin, “Yangsim pyǒngyǒk kǒbuja: sugam chung igǒna ch’urok hu sahoe pongsa” (COs – either imprisoned or engaged in voluntary activism after release), Daily Kyǒnghyang sinmun, December 31, 2006

“Sinbyŏn g 100 il hyuga p’eji, chŏnggi hyuga oech’ul ilsu chojŏng” (The 100 days-long leave for the newly drafted is abolished, the number of regular leave days is being reduced), Kukchŏng pǔrip’ing, January 3, 2008

Melanie Springer Mock, Writing Peace: The Unheard Voices of Great War Mennonite Objectors, Cascadia Publishing House, 2003

“Modǔn p’ongnyǒk kwa moryǒk e pandaehanda!” (I object to violence and military force in all forms!), Weekly Hangyǒre21, Issue 352, March 27, 2001

Moon Seungsook, Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea, Duke University Press, 2005

Na Kich’ǒn, “Kungmin 72% ‘Taech’e pongmu antoenda, kundae kaya’” (72% of citizens say that alternative service should not be introduced, and [COs] should serve in the army), Daily Segye Ilbo, October 29, 2005

O Sanghŏn, “Hannara, sahyŏngje kukpobŏp p’eji ‘sigi sangjo’” (Grand National Party – “too early” to repel death penalty system and National Security Law), Daily Mŏni T’udei, November 12, 2007

Ǒm Kiyǒng, “Kun ǔimunsa chinjǒng 600 kǒn nǒmǒ” (The number of petitions on suspicious deaths in the army surpasses 600), Daily Kungmin Ilbo, January 4, 2007

“Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et Spes”

Natasha Persaud, “U.S. base expansion in Korea sparks protests”

Pyǒngmuch’ǒng (Military Manpower Administration) ed., Pyǒngmu Haengjǒngsa (The History of Military Manpower Administration), Seoul, 1985

P’yo Myǒngnyǒl, “Nu ga kamhi? Nohǔi ga sagwan hakkyo rǔl ara?” (Who dared? Do you know the Military Academy?), www.ohmynews.com , February 14, 2007

“Sasǒl: Chajungchiran in’kwǒnwi, issǒya hana” (Editorial: Internal strife-ridden Human Rights Committee – should it exist?) , Daily Heraldǔ Kyǒngje, September 27, 2006

“Sasǒl: Pyǒngyǒk ǔimu nǔn pundanguk ǔi yangbohal su ǒmnǔn kach’i da” (Editorial: Military duty is a value a divided nation cannot yield on), Daily Segye Ilbo, December 10, 2006

Sin Chungsǒp, “’Chujǒk kaenyǒm’, pyǒn’gyǒnghaeya hana?” (Do we have to change the ‘main enemy” concept?), Munhwa Ilbo, November 23, 2004

Sin-Yuk Tonguk, “Ch’oe Chin: ‘Ai dǔl kwa p’yǒnghwa rǔl yaksokhan gǒryo’” (Ch’oe Chin: ‘But I promised to [serve the cause of peace] to my pupils’), Weekly Hangyǒre21, May 19, 2004

Sin-Yuk Tonguk, “Han’guk k’at’ollik ch’oech’o ǔi pyǒngyǒk kǒbu!” (The first CO among Korean Catholics!), Weekly Hangyǒre 21, Issue 583, November 1, 2005

Sin-Yuk Tonguk, “Tayanghan yangsim, kamokhaeng sijaktoeda” (Diverse consciences begin their way to prison), Weekly Hangyoreh21, Issue 519, July 21, 2004

“Taet’ongnyǒngnyǒng che 283ho chaehakcha chingjip yǒn’gi chamjǒngnyǒng” (Presidential Decree No. 283, Provisional Draft Deferment for the Students), Kwanbo (Official Gazette), February 28, 1949.

“Taet’ongnyǒngnyǒng che 1183ho chaehakcha chingjip yǒn’gi chamjǒngnyǒng p’yeji ǔi kǒn” (Presidential Decree No. 1183, Abolition of the Provisional Draft Deferment for Students), Kwanbo (Official Gazette), November 7, 1956.

“Tragedy and reform in the military”, Korea Herald, December 29, 2005.

Alfred Vagts, A History of Militarism, New York: Meridian Books, 1959.

“Yangsimjǒk pyǒngyǒk kǒbu wa taech’e pongmu” (Conscientious objection to military service and alternative service), Daily Hangyǒre, January 8, 2006