Preparing Okinawa for Reversion to Japan: The Okinawa International Ocean Exposition of 1975, the US Military and the Construction State

Vivian Blaxell

“Everywhere it is machines – real ones, not figurative ones:machines driving other machines, machines being driven by other machines, with all the necessary couplings and connections.” Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

Japan’s war for empire in Asia had many endings: the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the imperial broadcast announcing acceptance of surrender terms, “suffering the insufferable”; signing of the surrender instrument on the deck of the USS Missouri; promulgation of a new constitution; the last execution of a convicted Japanese war criminal, Nishimura Takuma; American implementation of the Treaty of Peace with Japan; the 1964 Tokyo Olympics; establishment of the Asia Women’s Fund to compensate the former comfort women (1995). But no one of those endings was more protracted and potentially more recuperative of Japan’s view of itself than the reversion of the Ryūkyū Islands to Japanese rule on May 15, 1972 after 27 years of direct American military control. Reversion did not go uncontested among Ryūkyūans. Memories of the entrepôt Kingdom of the Ryūkyūs and its final annexation by Meiji Japan in 1879persisted: independence was the impossible possibility. But the hand of the Pentagon had been so stern, so deforming on the Ryūkyūs,and the realistic alternatives so few, that reversion to Japanese sovereignty seemed better to many Ryūkyūans than continuing as America’s China Sea military outpost complete with nuclear weapons. Yet, at the point of reversion and in the 38 years since reversion, Japanese sovereignty was a mask: the US occupation of the Ryūkyū Islands continued undiminished, but now Tokyo and not Washington paid most of the bill; Japanese sovereignty in post-reversion Okinawa continued “to be subject to the over-riding principle of priority to the military, that is, the US military.”1

On the day of reversion, it rained. There had been protests against reversion in Japan and in the Ryūkyūs, but now there were street marches, speeches, celebrations, and an approaching tide of laws and policies and plans made by Tokyo, all designed to reterritorialize the Ryūkyū Islands into Okinawa, into Japanese space, and to give heft to the gauze of Japanese sovereignty. Political reversion entailed territorial mobility, the U.S.-governed Ryūkyū Islands moved, becoming Okinawa Prefecture again in territory bounded by Japanese title but dominated by American military policy. As part of this movement, Tokyo set aside budget and marshaled corporate sponsorship for an international exposition to be built and held in 1975 near Motobu, a very small townon the Motobu Peninsula in the north of Okinawa Island just a short journeyfrom Nago City. During the time of the Ryūkyū Kingdom there had been a collection of villages here. One of those villages, Nuwha, is the setting of a famous Ryūkyūan love song still sung today:

伊野波の石くびり

無蔵連れて登る

にやへも 石くびり

とさはあらな

The steep cobbled street of Nuwha

Is very hard

Yet, when walking and talking with my love

I want it to go on forever

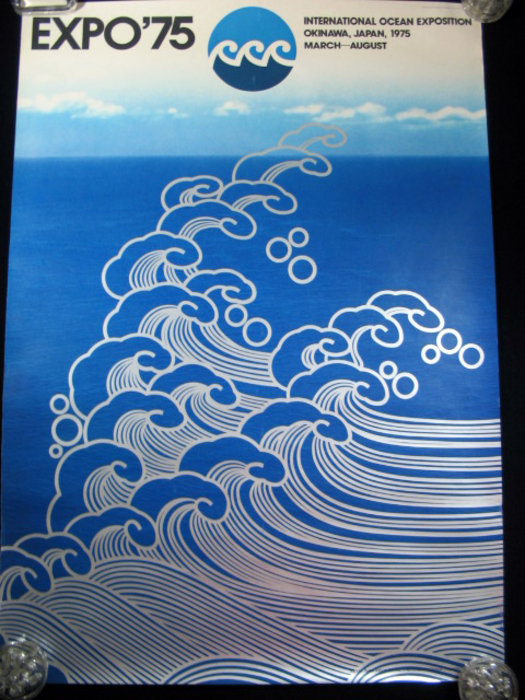

In this nostalgic, relatively remote, provincial place, in this very local place, Japan built Okinawa Kokusai Kaiyō Hakurankai; the Okinawa International Ocean Exposition: Expo 75. The exposition occupied 1 million square meters of land and sea. It hosted the pavilions of 37 countries. Crown Prince Akihito made a speech at the opening ceremonies and James Michener was the keynote speaker. With its centerpiece, Aquapolis, Expo 75 celebrated the reversion of the American-controlled Ryūkyū Islands to Japanese rule as Okinawa Prefecture. As one Japanese report from the time put it, Expo 75 was integral to shinsei Okinawa-ken, the “reborn Okinawa Prefecture.”2

Expo 75 Opening Day Ceremonies

Expo 75 was a grand affair designed to make the insubstantial seem substantial, to make a narrow ambit appear broad, and to produce and release the Japanese state and its intimate connections with capitalism and imperial history into the regained prefecture. And given the limits of the renewed Japanese sovereignty in Okinawa, the task of producing and projecting what sovereignty there was fell heavily on Expo 75. But how are we to apprehend the tasks of Expo 75 in all their complexity, connectivity, productivity and, yes, in all their emptiness? World fairs and international expositions have been well-studied, variously conceived of and interpreted as symbolic universes ritualizing and affirming dominant social, economic and political orders,3 as pedagogical strategies, models and sets of lessons “of what the future might look like [and] how it may be brought about”,4 as spectacles imposing hegemonic meanings onto a depoliticized mass audience5 and as metaphors for colonial and/or economic orders of power.6 Each approach tells us something about the operations of expositions and world’s fairs, but not enough. Expositions are more than materializations of hegemonic discourse; they are more than architectural and visual metaphors for prevailing relations of power and capital. Expositions and world’s fairs are more than themselves.

A Poster for Expo 75

Machinic thinking reveals this more. In what follows below, machinic thought is a mode of thinking about Expo 75 that conceives of it and pulls it apart as machine or machinic device, rather than mechanical device, in the sense that machine and machinic are conceptualized in the work of Gilles Deleuze and in Deleuze’s work with Félix Guattari. The advantage of machinicas opposed to mechanical thinking about Expo 75 is twofold. First, both discourse and techne can be seen together and apart as machines doing what machines do: production. In this way, machinic thinking recovers the Marxist understanding of machines as constantly multiplying agents of capitalist production and enslavement, but by taking mechanical devices as at once techne and abstraction, and discourse as both techne and abstraction, machinic thinking evades the problem posed to agency by metaphor while collapsing the erroneous distinction between base and superstructure in upon itself. Ideas, capital and the means of production then are all machines composed of machines, and all machines are both produced by, expressive and productive of the “social forms capable of generating them.”7 Whereas the one existing study of Expo 75 by Tada Osamu8 sees its subject as a metaphorfor dominant social forms, a sign of something else, machinic thinking turns Expo 75 into the social form itself.

Machinic thinking also emphasizes the radical connectivity and proliferation of machines. Machines are comprised of other machines connecting over and over again with still more existing machines, and with time and space, to produce new machines, which then connect with other machines. When it comes to the study of Expo 75, this idea of machinic connectivity and proliferation is especially important for it permits us to understand Expo 75 well beyond the abstract and technical material bounded by its gates and beyond the scholarship of representation and metaphor. Like other Deleuzian machines, Expo 75’s job was to aid and abet reterritorializations of space, matter and thought through production and release of social forms that resulted in both enslavement and subjectification, and it did so by connecting with other abstract and technical machines, producing more machines which acted upon the spatial and social territory of Okinawa at reversion to vary and mutate it9 in ways serving the strictured ambit of Japanese sovereignty. Everything about Expo 75 connected with other machines, abstract and technical, from the machine of the 1970’s Japanese state in its multiple embraces with developmental capitalism, to the machines of historical memory, landscaping and avant-garde architecture. Through these machinic connections, Expo 75 produced technocracy, nationalism, religion, knowledge capital and design aesthetics in Okinawa in ways that made the mask of return of the Ryūkyū Islands to Japanese sovereignty seem almost real, seem to be the face itself.

The theme of Expo 75 was marine and futuristic: “The sea you want to see.” There was a small crack in the mask of Japanese sovereignty here, for in its seemingly innocuous theme, Expo 75 connected with more serious matters and looped around back to the decades of American military enslavement of Okinawa. Despite Japanese sovereignty, Okinawa remained a linchpin in the Cold War military strategy of the United States, a Deleuzian “war machine.” By 1960, military oceanography and ocean exploitation constituted an important part of Cold War strategy for both the Soviet Union and the United States, primarily because the development of ballistic missile submarines and the Polaris, Chevaline, Poseidon (US) and R-13 and R-21 (USSR) submarine launched ballistic missiles had reterritorialized the sea as a prime site for intercontinental nuclear strikes and what Paul Virilio might call the absolute and terrifying peace of nuclear deterrence, mutually assured destruction. The theme also connected Expo 75 with another machine: the international political economy of energy and its plans to exploit the oceans as sources of minerals, natural gas and oil. For Japan in particular, insular and mountainous, the sea promised solutions to increasing concerns about burgeoning population and finite resources, the latter anxiety brought to a head in 1973 when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries imposed an embargo on oil sales. The problems of energy supply and demand drove a substantial proportion of Japanese state policy and economic planning. The connection of Expo 75 to the energy issue dragged Okinawa into the territory of Japanese national interest, an habitual place for the Ryūkyū Islands in both Japanese discourse and practice since the archipelago was first defined by Tokyo as the southern gate of the modern empire and thus needing incorporation into the modernizing 19th century state.

Furthermore, “The sea you want to see” connected Expo 75 with Okinawa and Okinawa with the proliferating and machinic complex of Japanese tourism. Speaking the language of the sea, Expo 75 was to unite Okinawa and the main islands of Japan as one but more importantly, the theme of sea, desire and the future was to instate “Hawai’ianization” of the Ryūkyūs.10 If the Ryūkyū Islands were becoming Okinawa Prefecture again, Okinawa Prefecture was also becoming something in addition to a US military base and a Japanese border region. It was becoming aoiumiaoisora (blue sea, blue sky), a resort and site of pleasure for Japanese. The advantages and possibilities of turning the islands, especially the main island of Okinawa, into a simulacrum of resortified Hawai’i, itself a copy of South Pacific islands and their representations in the cinema, had been discussed since the 1960s, but the American authorities had blocked this sort of Japanese investment in the islands.11 At the time of reversion, apart from a few new hotels, some plantings of palms and hibiscus, and improved training of personnel for service of the existing beach and war memorial tourist trade, little had been done to turn the Ryūkyūs into Japan’s Hawai’i. Expo 75 changed that. Tada Osamu describes what he terms a complete “resortification” of the islands coincident with reversion from American military rule to Japanese sovereignty in 1972 and finally delivered by Expo 75.12 This production of commodity tourism constituted an important dimension of the mask of Japanese sovereignty in Okinawa. Beach resorts, ocean landscapes, theme parks and packaged representations of Ryūkyūan culture concealed the facts of the American war machine and Japanese complicity with it. Parts of Expo 75 looked and functioned like a beach resort and Expo 75 promotional materials teemed with idyllic images of sun, blue sea and blue skies. From these parts, Expo 75 produced both other resorts (techne) and the abstract machine of commodity tourism in Okinawa. Here there was a significant connection with massive socioeconomic transformations in Japan resulting from high rates of economic growth since the end of the 1950s. By 1975, the Japanese economy was ready for mass-market tourism, for new service industries and for places as commodities. And mutating Okinawa into Japan’s own Hawai’iseemed to promise some solution to Okinawa’s poverty. It promised to balance radical economic asymmetry between Tokyo and Naha, while opening up opportunities for Okinawan businesses and addressing chronic local unemployment. The promises went largely unmet.

In financial terms, many of the actors at Expo 75 had also been major players in the Japanese Empire before 1945: the government, Mitsubishi and Fuyō Group (formerly the Yasuda zaibatsu) for example. The government contributed an estimated ¥180 billion and the Okinawa Ocean Exposition Association, a quasi-government organization, contributed ¥30 billion to the cost of building infrastructure. Mitsubishi and other big businesses contributed billions of yen either as cash or as technology, time and labour. Although most of the cost of development and management was borne by the state and its cohort in big business, at least one major personality from the imperial time made a sizeable contribution to the exposition: the ultranationalist, Sasakawa Ryōichi. Sasakawa’s Japan Motorboat Racing Association and Japan Shipbuilding Industry Foundation contributed ¥30 billion to the construction and operating costs of Expo 75.13 This was a very significant amount indeed, approximately USD$107 million and if adjusted to reflect an average US inflationrate of 4.54 percent between 1972 and 2009, would now have a purchasing power of approximately USD$530 million. And it came from the organizations of a man known for his ultranationalist and fascist beliefs and activities in Japan both before and after the war, during which latter period he had been arrested as a Class A war criminal for his activities financing Japan’s war in Asia and profiting from Japanese colonialism in Manchuria and China.14

The stakes were high and the responsibilities of Expo 75 manifold. The decision to situate Expo 75 adjacent to a small and impoverished village on a remote and rural peninsula was exemplary of the functions it was to perform. In its last year of office as interlocutor between the US military command and the people of Okinawa, the Government of the Ryūkyūs chose Motobu for Expo 75, but the decision relied on approval from Tokyo.

Motobu made an unlikely site for an international exposition. Previous international expositions had been held in major metropolitan areas (Stockholm, Paris, Brussels, New York, Seattle, Osaka, Montreal) or in significant provincial cities such as Spokane, San Antonio and Naples. But the condition of Motobu served the main Japanese agenda: the area’s lack of infrastructure represented a surface on which the Japan that Gavan McCormack calls the doken kokka or “construction state”(itself a machine comprised of machines) could write itself without interruption by building Expo 75 and all that was necessary to make Expo 75 possible in Okinawa.

Motobu before Expo 75

By 1975, the impact of two successive centralized Comprehensive Development Plans on industrialization and infrastructure and socioeconomic formations since 1962 had produced a metamorphosis in the Japanese national space that was nothing short of astonishing: a high-flying leap toward national integration powered by designated industrial zones, an automating and globalizing automobile industry, construction of a new state-of-the-art national communications system, sanitation, television, a cutting edge national transportation network that included freeways and the world’s first super high speed train, shinkansen, and the expansion of a consumer society driven to shop by a constructed craving for the Three Cs: color television; car; cooler. Expo 75 connected to the construction state and to the infrastructural and capitalist machines produced by the construction state; itproducedthis high speed, high tech, networked, planned, constructing and consumerizing Japan and released it in Okinawa.

Motobu after Expo 75: Note the Motobu Bridge as well as hotels and other infrastructure on the far side of the bridge, all built for Expo 75

Sakaiya Taichi, head of Japan’s Economic Planning Agency and a central figure in the construction state, was deeply engaged in planning for the exposition and he brought with him to the project the modernizing and technocratic assemblage that was the Japanat the time. Motobu provided Sakaiya, the Government of the Ryūkyūs, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and their private sector cohorts, Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Hitachi and Matsushita, with an exemplary site for production of the state, its meanings and its powers in Okinawa. Motobu is 85 kilometers from the international airport at Naha. Roads had to be built. Motobu lacked an electricity supply adequate for the Expo 75 project. A new power grid had to be built. It lacked the necessary sewage and water supply facilities. Motobu did not have hotels and inns, living accommodations for Expo staff, medical facilities and almost every other infrastructural facility necessary for such a large project. Of the total government funds for Expo 75, ¥72.2 billion was spent on widening existing roads and building the Okinawa Expressway and National Highway 58.15 Motobu’s population increased by approximately 3,000. A bridge was built across the harbour. The Naha Nikko Grand Castle Hotel, the Okinawa Harbor View Hotel Crowne Plaza in Naha and numerous other hotels and guest facilities in and around Motobu were built with public funds or with the support of public funds to service Expo 75. The investment was enormous; though little of the funds reached Okinawan pockets, the Expo 75 project enriched hondo construction companies, but in these ways Expo 75 functioned as Deleuzian machines do: it connected with other machines and reproduced them in Okinawa and produced new machines both technical and abstract — the tourist industry, hotels, Okinawa as Hawai’i, the construction state in Okinawa, highways and the idea of speed, infrastructure, a mutated town of Motobu. A coalition of powers — construction state, commodification, government, big business, Sasakawa money — produced Expo 75 to produce themselves in Okinawa and in so doing, enmeshed the reverted prefecture, previously and still enslaved by American military policy, in the networks of Japanese capitalism.

This second enslavement relied upon demonstration of what Okinawa did not have as much as it relied upon demonstration of what Japan could do for Okinawa. If Expo 75 produced the Japanese construction state and its connections in Okinawa as the substance of renewed sovereignty, it also revealed a steep escarpment between the Tokyo plateau and the Naha plateau, an asymmetry with its geneaology in the 19th century, now renewed and over-coded by the site of Expo 75 and by Expo 75 itself. At Expo 75 the recovered tatter of empire and the state came together in a power relation predicated on adisplay of technology that simultaneously affirmed Tokyo’s postwar and post-1964 Olympics choices “in the sphere of production and in the consumption implied by that production”16 and underlined the failure of Okinawa’s status since 1945 when it had been occupied by the United States. Such asymmetry was most dramatically reproduced by the Expo 75 centerpiece, Aquapolis, which is discussed below, but the whole of Expo, its internal components and its sprawling connections to development, construction and infrastructure, also served to produce and illustrate the fundamental imbalance between Okinawa and metropolitan Japan. Sumitomo, Hitachi, Mitsubishi, Fuyō Group, WOS Group, Sanwa, Mitsui and Matsushita all had pavilions at Expo 75. These functioned as Deleuzian machines function, comprising the larger Expo 75 machine and connecting to and producing other machines. The architecture of the pavilions tended to be futuristic and technocratic. The displays used the latest available technologies, such as video imaging, computerized displays, multiple giant movie screens, futuristic sound and moving footways to present both a corporate version of the future and the sea and to foreground corporate goods and services that were far beyond the means of most Okinawans. Japan’s first completely automated transportation system (AGT) was introduced at Expo 75,17 a driverless people mover built by Kobe Steel there on the provincial landscape exposing the dissonance between Okinawa and Tokyo: Japan, powerful enough to make things move by themselves; Okinawa to be moved on. Even the Okinawa Pavilion accentuated the disparity between the archipelago and the main islands of Japan. Its theme was intended to be local, an articulation of the importance of the sea in Okinawan history and culture, but by the time the pavilion opened in 1975, the theme was more about showing how the sea had globalized Okinawa over the centuries and now integrated it with Japan.18 Traditional housing provided the inspiration for the design of the Okinawa Pavilion, but the final building was so large, so precise and so modernist in its concrete forecourt with fountain and cylinders for seats that the architectural gesture to the local only made traditional housing remarkable for what it was not, not for what it was. The task of the Expo 75 machine was to produce a mask of Japanese sovereignty in Okinawa and to generate development. It did both, but the result confirmed Okinawa’s peripheral condition. There was both a promise and a threat in the production of the construction state in Motobu: this is what Tokyo can do for Okinawa and this is what Tokyo can do to Okinawa.

Expo 75’s productions of the construction state in Okinawa and its Hawai’ianization of Okinawa depended heavily on expurgation. Three Okinawan bunkajin (cultural figures) were selected by the Okinawa Ocean Exposition Association to guide the principles and themes of the Okinawa Pavilion. One of them, Ōshima Tatsuhiro, writer and winner of the 1967 Akutagawa Prize, made the following proposal for the theme of the Okinawa Pavilion:

For Okinawa the sea is both a mother blessing us with resources since ancient times and a road bringing culture from abroad. However, for Okinawa, the sea also represents aggressions beginning with the inroads of the Satsuma domain in the beginning of the 17th century, the road to the Pacific War and now the American military bases. Is not Expo 75 an opportunity to perhaps recover these original meanings of Okinawa’s seas?19

Ōshima’s proposal met with unanimous approval from the other members of the association but later, the head of the association observed that the Americans were worried that some of the proposed themes could be seen as insinuations (atekosuri 当て擦り) and Ōshima’s proposals were dismissed, thereby establishing the tacit code of the machine that the problems of the Pacific War and American military bases in Okinawa would not collide with Expo 7520 whilst also exposing the fictions of Japanese sovereignty in the archipelago.

And the expurgations multiplied. The exposition site next to Motobu was chosen in part because of its natural beauty. The final design for the traverses, open spaces and slopes of Expo 75 connected to the surrounding area and transformed the site itself and territories within visual range into landscape. Landscaping entailed mutations of territory and territorial meanings through aesthetic practices. For example, the pathways and main plaza of Expo 75 were designed to perfectly frame the adjacent small island of Iejima. Landscaping of Iejima mutated territory through a connection to the shakkei or “borrowed scenery” technique, a method of incorporating a distant vista into the composition of a garden or a city, which is central to Japanese ways of doing landscape and originated in its Japanese form in the 11th century.

Shakkei is an aesthetic mode of both deterritorialization and reterritorialization, one in which the disjunction between inside territory and outside territory is overcome: outside is brought in and inside migrates out, and it might not to be too much to suggest that the practice of shakkei by the Japanese construction state at Expo 75, overcame the inside/outside distinction residual in the situation of reversion. More specifically, as Tada Osamu points out, the perfect view of Iejima designed into Expo 75 aestheticized Okinawa and prepared it for final Hawai’ianization, a commoditizing territorial movement necessary for a specific sort of post-reversion Okinawan identity in Japan.21

Here, Expo 75 connected in yet another way the construction state, tourism, and Japanese aesthetics with Okinawan time and space, and here, a considerable mutation occurred, one that sought to incorporate Okinawa within a Japanese topos through historical expurgation. One of the most savage of the many very savage battles between Japanese and American troops in Okinawa was fought on Iejima in early 1945 and resulted in the deaths of around 3,500 civilians and Japanese troops. Further, the old Iejima airfield, since replaced by a new and under-utilized airport built for Expo 75, was the point at which Japanese officials carrying the official instruments of Japan’s surrender disembarked from Japanese bombers and boarded American military aircraft for the remainder of their journey to the Philippines where they met with Douglas MacArthur’s staff at Corregidor. As borrowed scenery at Expo 75, all of this became something else: history expurgated and replaced by landscape. That is not to suggest that local history and its meanings did not retain their full cogency when Iejima was viewed from outside Expo 75. And it is fair to assume that Okinawan visitors to Expo 75 retained their local literacy when it came to reading the view of Iejima framed by the exposition, despite the fact that it elided not only the battle for the island but the continued anti-base struggle waged by Iejima residents subsequently.

Shakkei: Iejima and Gusukuyama framed and borrowed by Expo 75

Yet, the great majority of the nearly 3.5 million visitors to Expo 75 were not Okinawan and for these visitors (mostly Japanese) the Iejima produced by shakkei framing was surely innocent of local meanings. The design of space and spatial traverse at Expo 75 entailed a significant attempt at subjectification: visitors ran the risk of seeing things the way the machine wanted them to. It also meant that Iejima’s history and the history of the Japanese empire underwent a forgetting, a mutation into something beautiful, a landscaping of the past. Although Japanese tours of “Southern Battle Sites” were commonplace by 1975,22 war memorials, the glorious imperial war dead and all that they implied about Japan’s defeat and the dismemberment of its empire, including the loss the of Ryūkyū Islands, were not part of the Expo 75 machine and its enunciations, unless by omission, the nagging shadow of the unspoken.

The production of Iejima as an expurgated landscape also made a refracted connection back to an older Japanese way of doing colonialism in the Ryūkyū Islands: the folding and expurgating of Ryūkyūan religious practices and territories of faith. In the late 19th century, the Japanese imperial-signifying regime imposed dōka, assimilation, across the empire. Inserted into colonial Okinawa, dōka acted machinically to connect to Ryūkyūan society and culture and to mutate them into national material. Dōka prohibited some Ryūkyūan practices, permitted others, mutating, enfolding, and expurgating as needed to complete the movement of the pre-1945 territory from Kingdom of the Ryūkyūs to Okinawa Prefecture and the extension of Japan to the Ryūkyū Islands. Religion and belief were especially affected. After annexation in 1879, Japanese Shinto folded Ryūkyū shrines and sacred spaces into the ideals of saiseiitchi, governance by a deified ruler according to religious rule. Shuri Castle, the sacerdotal center of the Ryūkyū Kingdom and residence of the Ryūkyū monarchs, who were both political and religious figures, was left to decay after the Meiji government deposed the last Ryūkyū king, Sho Tai, and sent him into exile in Tokyo, thereby expurgating the political and spiritual meanings of the castle. In 1925 Tokyo transformed Shuri Castle into the main Shinto shrine for Okinawa, a dōka of territory folding the castle into the politico-spiritual regime of the modern Japanese state.23

Borrowing of Iejimaat Expo 75 to produce a landscape for the fictions of Japanese sovereignty both expurgated and folded Ryūkyūan spiritual territory into the Japanese construction state in an operation similar to the ways in which dōka had expurgated and folded Ryūkyūan religion and spiritual spaces into a 19th century Japanese topos. The view of Iejima from the main avenue and the plaza was, and still is, remarkable for the sharp peak of Gusukuyama, an erosion artifact resembling a weathered mountain. Along with the caves of Sefa Utaki, the little island known as Kudakajima and the area around Nakijin Castle on the Motobu Peninsula, the eroded peak of Gusukuyama is one of the most important sacred spaces in the Ryūkyū Islands, operating as a guide to Ryūkyūan sailors and as a place where people pray for safe voyages, good harvests and good health: a territory of faith. But when Expo 75 connected with Gusukuyama, matters changed. Distant mountains are the most frequently borrowed scenery for Japanese shakkei landscaping24 and where there is not a mountain to borrow, rocks may be gathered and grouped to represent mountains in the garden, or sand may be shaped and packed into the shape of a mountain, as at the garden of Ginkakuji in the Sakyō-ku district of Kyoto.

Shakkei, Mt. Hiei borrowed as scenery for the garden at Shoden-ji, Kyoto

The sacred mountain constructed in the garden at Ginkakuji

The making of mountains in Japanese landscaping, whether borrowed or constructed, recreates a Japanese territory of faith in the garden. Mountains possess very substantial spiritual power and significance in Japanese Buddhism and in Shinto. Shumisen, the cosmic mountain, is at the center of Japanese Buddhist spiritual geography, the core of the universe, and migrated from Hinduism to Buddhism, from South Asian Buddhism to China and from China to Japan in the 8th century when Nara Period sinification released Buddhism into the land. Just as the sand representation of Mount Fuji at Ginkakuji recreates a specifically Japanese sense of the sacred world order in the temple garden, so too the view of Gusukuyama from Expo 75 recruited and folded indigenous Ryūkyūan faith into Japanese sacred territory, a Japanese topos, where it became panorama, a cog in the reterritorialization of the Ryūkyū Islands as Okinawa Prefecture, as Japan and an element in the claim of sovereignty.

Deleuzian machines not only connect to and produce other technical and abstract machines, they are comprised of machines. As I have indicated above, we can see each pavilion and installation at Expo 75 as a machine in itself, charged with connections to and productions of the social formation from which it came. But the most important machine within the Expo 75 machine was Aquapolis.

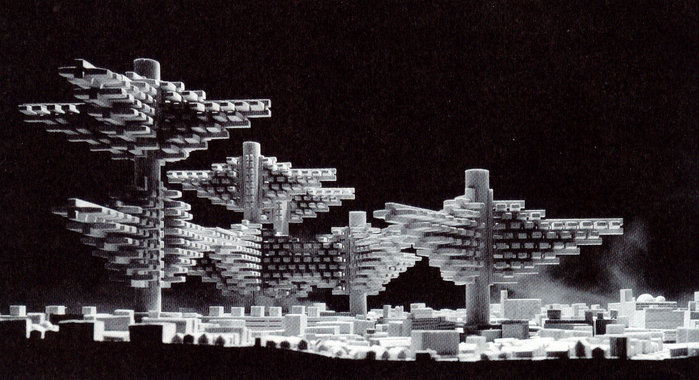

The design and architectural aesthetic of Expo 75 owed something to Expo 70 at Osaka whereavant-garde architecture, design anda patina of futurity hadreplaced the exhibits of manufactured goods and fabricated ethnicities typical of expositions and world fairs in the Fordist era. In the view of the Government of Japan, the success of Expo 70 had owed much to the involvement of Japan’s Metabolist architects, and it was to Metabolism that the Expo 75 managing committee turned for design of the centerpiece of Expo 75: the machine inside the machine. The Metabolists had vaulted onto the international architectural scene with a design manifesto presented at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo. They were especially concerned with the city and with urban living in an age of rapid technological innovation and mass society. Metabolists proposed an architecture for city living that could reproduce in techne the organic transformations nature makes in response to changing conditions. They conceived of both cities and the buildings within cities as metaphors of natural organisms, built synonyms of living matter, composed of cells that divide, change and die within a total body that lives on and develops. In 1960-62 Isozaki Arata designed Clusters in the Air, a concept for mass housing in Tokyo inspired by trees with the housing units as leaves and the access and service facilities as tree trunks and soon designs for metabolic, mutable buildings represented the cutting edge of Japanese architecture.

Clusters in the Air, Isozaki Arata

The Metabolist building and the Metabolist city were temporary ensembles, owing something to both the Buddhist concept of impermanence25 and to the Japanese tradition of cyclically disassembling and rebuilding structures,26 especially sacred structures, yet answering modern Japanese concerns and dynamics. Metabolist buildings, built communities and cities were to be floating systems, material machines that could be disassembled and reassembled according to the demands of an age marked by accelerated technological advances, economic development and massive urbanization and were designed to respond to the particularly Japanese pressures of overpopulation and limited land for urban expansion. Nomadic buildings. The technical demands of such experimental and visionary architecture meant that Metabolist design had to be deeply enmeshed in technological innovation, wedded to technology itself. Every built Metabolist structure pushed hard at the current limits of engineering and construction methods.

For this reason, Metabolist architecture had both everything and nothing to do with Okinawa. The design impulse of such Metabolist buildings as Watanabe Yōji’s New Sky Building in Shinjuku and Kurokawa Kisho’s Nakajin Capsule Hotel Tower in Shimbashi materialized Japan as the construction state, giving built form to the ideals of the time: technological innovation; engineering synthesized from multiple applications; rationalized urban living. In these rather fantastic buildings there is utilitarianism at the technical core of the fantasy. There is, too, a visual brutality in their organic forms, an impression of immobility in their supposed nomadism apparent in monumentality, visible engineering effort, modernist geometry. In view of the technical demands required by Metabolist architecture and its connection with the problems of dense urban living in Japan, it is not easy to account for it in provincial, rural and militarized Okinawa. But the decision to hire a Metabolist architectas the signature designer of Expo 75 represents another machinic connection, a connection between Expo 75, Okinawa, the urbanism of Japan and the marriage of the nation to technology. And yet, the asymmetry between capital and technology heavy Metabolist architecture and theory and buildings and life on the Motobu Peninsula also shows us how little Expo 75 had to do with Okinawa as it was: an impoverished border territory, furrowed by decades of devastating war, American military occupation, agrarian, and ambivalent about its history and its identity.

New Sky Building, Watanabe Yōji

Nakajin Capsule Hotel Tower, Kurokawa Kisho

As architect of the Expo 75 centerpiece the managing committee selected Kikutake Kiyonori, a founder of the Metabolist architecture movement. Kikutake had designed one of the signature structures of Expo 70 in Osaka: Expo Tower, which articulated Metabolist principles in its organic mesh of steel scaffolding and viewing/entertainment pods that could be raised and lowered, even removed and added if required.

Osaka Expo Tower, KikutakeKiyonori

Detail of Osaka Expo Tower, KikutakeKiyonori

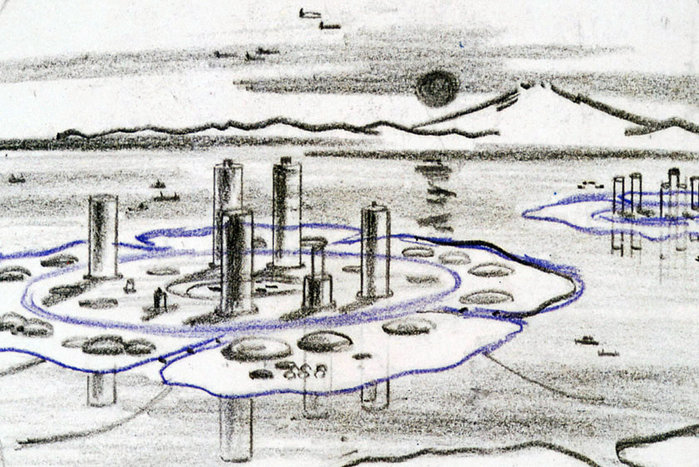

In 1958 Kikutake had designed and built his own home in the Tokyo ward of Bunkyo-ku as an opening declaration of his own Metabolist principles paying particular attention to the technological challenges posed by mutable structures. He designed the house as an elevated single large permanent living space with kitchen and bathroom and other service spaces attached to it so that they could be detached and moved according to his family’s needs. His children’s bedrooms were attached to the core living space as capsules that could be detached completely from the dwelling when the children left home.27 Also in 1958, the government of Tokyo called for plans to cope with the city’s growth. In response, Kikutake presented drawings and schemata for a floating city. The design was not realized but Kikutake persisted, developing concepts, schemata and plans for floating cities in 1961, two in 1963, 1968 and 1971. Here, Kikutake found a creative space in the intersection of Metabolist architectural principles with marine cities and his vision was so visionary, his grasp of the engineering challenges so thorough, that along with Buckminster Fuller and Paul Maymont, he became a leading figure in what Peter Raisbeck calls “one of the more curious minor architectural traditions of the 1960’s”: floating cities.28 In this space Kikutake elaborated a vision of nomadic, organically adaptable human habitats in previously uninhabitable territory that offered solutions to postwar Japan’s dilemmas about living space and the relationship between technology, change and human life. Kikutake’s floating cities were marine habitats in which human technology exploited the sea as both resource and living space; a rediscovery of smooth space which would lead, in Kikutake’s view, to human happiness.29 His vision was futuristic, technocratic, romantic, impossible. The technology did not yet exist. But there is a considerable deterritorialization and its concomitant, reterritorialization in Kikutake’s plans: his designs for floating cities moved human habitat from land, striated space, to sea, smooth space, and in that movement deterritorialized human habitat and reterritorialized the sea. In his floating city designs, the city was radically nomadized, it was modular and metabolic: not to be anchored at any fixed point. All or part of it was to be able to cruise to new moorings as necessary or desired. And at the end of its useful life, the floating city was to be sunk to the ocean floor, itself a mode of disassembly, nomadic movement, where it would be reterritorialized as a reef for marine life.

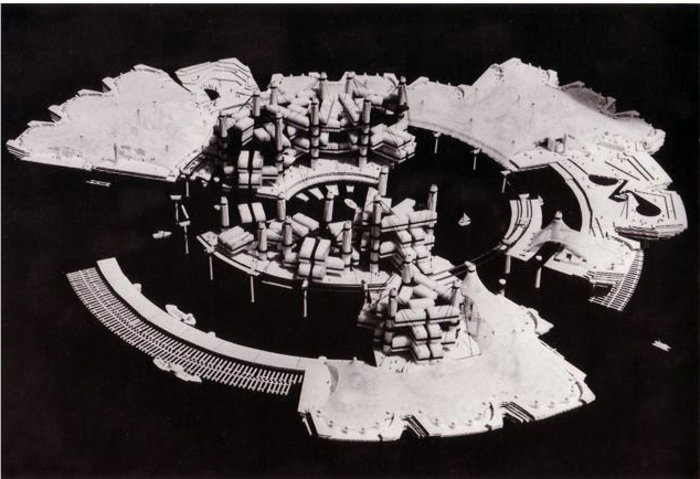

Sketch for floating city, Kikutake Kiyonori 1960

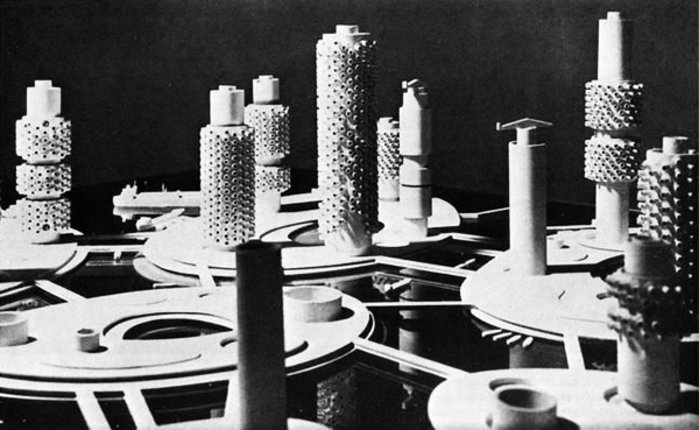

Model of floating city, Kikutake Kiyonori, 1962

Floating city, Kikutake Kiyonori, 1971

Kikutake’s record as a Metabolist architect with a successful structure at Osaka Expo and his expertise in the principles and engineering required for floating habitats fitted nicely with the futurist, technocratic and sea themes of Expo 75 in Okinawa, and he was contracted to design and build the Expo 75 centerpiece, a floating habitat, a city on the sea (kaijōtoshi) called Aquapolis. Aquapolis was the machine within the Expo 75 machine. In Okinawa, Aquapolis provided the engine of Expo 75 and distilled and producedthe essence of the Japanese construction state and its connections to science, technology and big business in Okinawa, promising parity but delivering only asymmetry in the already lopsided Japan-Ryūkyū Islands relation. The project was gargantuan in every way. Nothing like Aquapolis had ever been built before and the obstacles were many, beginning with the challenges posed by situating a built human habitat structure of such size on the sea:

In planning sea space as human habitat, unique terms and conditions may arise. First is the point that this is new space and so far we are inexperienced with it. Secondly, the conditions are three-dimensional and it is necessary to understand that the space is not only on the water, at the same time it is in the water, and moreover, basically movement is immanent in the space, and due to buoyancy there are special characteristics of the built environment. The sea is horizontal planed space, it is continuous space, it is the largest space on Earth, larger in the southern hemisphere than in the northern hemisphere.30

Solutions to the obstacles meant that the built Aquapolis bore only a vague resemblance to Kikutake’s early sketches and concept art, which evolved as engineering and technical dilemmas were confronted and resolved. Solutions to obstacles also proved expensive, so expensive that only the government could afford the ¥13 billion direct investment in it, but the project was considered so important to the national interest, additional development, construction and installation expenses were borne by Japanese businesses.

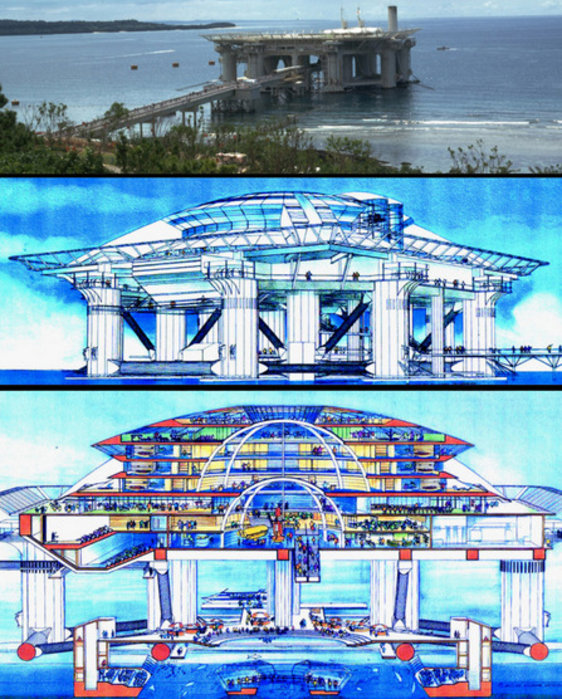

The evolution of Aquapolis from concept to realization

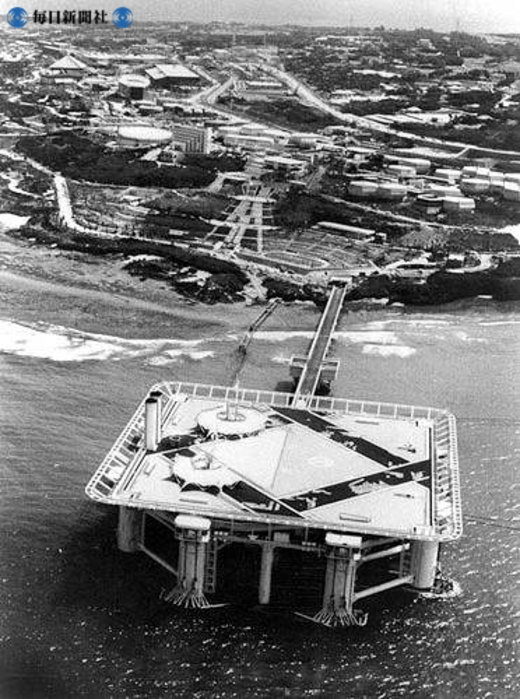

Although Aquapolis was to float in the sea off the coast of Okinawa in celebration of the Ryūkyū Islands becoming part of Japan again, Okinawa got none of the employment benefits, skills and technology transfer associated with construction. Instead, in a decentralized production process, Hiroshima Shipyard and Engine Works, a subsidiary of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, produced Aquapolis from parts manufactured elsewhere and transported by sea to Hiroshima for final assembly and trials. The structure was to be so large that the company had to build a new wet dock to accommodate it.31 After extensive sea trials in the Setonaikai, tugboats towed Aquapolis more than 1000 kilometres to Motobu in Okinawa.

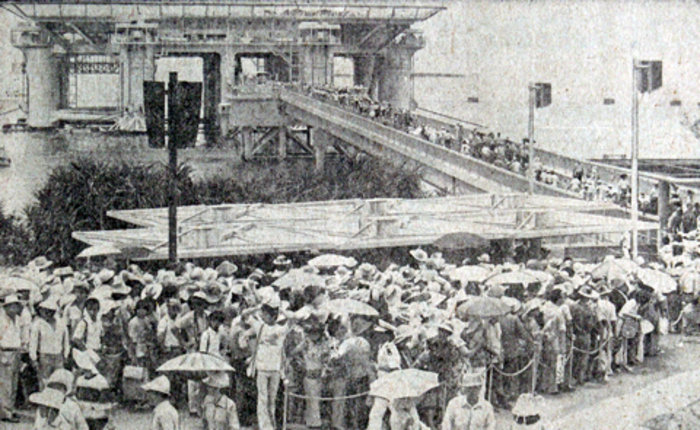

Crowds line up to visit Aquapolis at Expo 75

Aquapolis

It is almost impossible these days to appreciate the sheer size of Aquapolis and the mobility of that size. Most photographs do not do it justice; only in scenes where Aquapolis rides the ocean billows caused by the approach of a typhoon in Matsuyama Zensō’s 1976 documentary film, Okinawa Kaiyōhaku (Okinawa Ocean Expo), can we begin to apprehend the enormity and power of this floating machine. The 10,000 square meters, multiple deck structure weighed 15,000 tons and represented the final landing place of a line of flight begun in the late 1950s with the emergence of a techno-romantic vision of cities on the sea. Aquapolis was constructed as a semi-submersible, welded, cubic structure made up of decks, lower hulls, columns and braces. Megafloat technology remained in the future and so Aquapolis moved in correspondence with the tides and rough seas. A 250-meter bridge constructed to elastically withstand severe climatic and tidal conditions connected Aquapolis to the shore. Sixteen permanent anchors fixed on the seabed tethered the structure at the end of sixteen expandable chains controlled by motorized windlasses. By lengthening or shortening each anchor chain, it was possible to move Aquapolis a further 200 meters out to sea. Drainable ballast tanksalso made it possible to adjustfor mobility (towing) or for semi-submerged stasis. The lower decks contained a variety of urban and residential facilities, including a display area, a machine room, a dining room, a kitchen, aclerical office and a First Aid room, in addition to a rest, information and telephone area, a post office offering international services, rooms for visiting VIPs and staff officials, a central control room, a utility control room, a computer room and a residential area for about forty employees. Aqua Plaza on the upper deck featured lawns and a heliport.

Aquapolis from the air

Aquapolis was largely self-sufficient when it came to energy and one of the world’s first waste water recycling processes was tested there. Once in Aquapolis, visitors could ride a moving footway through three main exhibits, all of them devoted to the sea theme of Expo 75: Marinorama, a static dioramic representation of the primeval ocean; Sea Experience, an observation gallery; Sea Forest, a representation of the flora of the ocean floor. The exhibits were trite, for it was Aquapolis itself that was the attraction and the main exhibit. Aquapolis was huge, but it was also a much-reduced realization of Kikutake’s earlier concepts for floating cities. In his view, however, Aquapolis at Expo 75 was but one prototypical module of a larger metabolic floating urban structure to be composed of other floating and detachable modules linked together on the surface of the sea.32 The engineering and design of Aquapolis drew on Kikutake’s fifteen years of research and on advances in the defense, transport and mining industries. Aquapolis was the machine at the heart of the Expo 75 machine, intensively productive of Japanese capitalism and the creative and technological imperatives driving it. Every part of Aquapolis reproduced the networks of Japanese capitalism in Okinawa. For just one example, the 3445 square meter tensile membrane canopy on the upper level alone required new technologies and new strategies of production involving multiple sectors of the 1970s’ Japanese economy: the design skills of Kikutake and his associates; Takenaka Corporation for construction; Shimizu Corporation for canopy engineering; Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for metal and chemical components; Osaka Tents Corporation for webbing and rigging supplies. In interviews, papers and presentations, Kikutake made a point of noting how design and construction of this new floating city stimulated a previously unimagined integration of different sectors of Japan’s economy, bringing together sciences, technologies and methods from the shipbuilding, rolling stock, machine and public works industries to create a new “human habitat industry” as he called it.33 Other designs for floating living, such as Kikutake’s earlier project, Unabara, Paul Maymont’s floating extension of Monaco, Buckminster Fuller’s Triton City project and Thallasopolis I, a floating city of 45,000 designed by Jacques Rougerie and intended for the fishing communities of the Banda Sea in Indonesia, had not been built: the techno-romantic vision of these architects exceeded the possibilities of the technology. And Aquapolis, though hugely reduced from the grand visions of floating cities that preceded it, would not have been built either were it not for the financial and technological investments of the Japanese government and big business, Mitsubishi in particular. This powerful concentration of public funding and private investment is a testament to the importance of Aquapolis (and Expo 75) in the production of Japanese sovereignty in Okinawa after reversion.

As Deleuze and Guattari note, “One of the fundamental tasks of the State is to striate the space over which it reigns, or to utilize smooth spaces as a means of communication in the service of striated space.”34 The marine theme of Expo 75, itself devised by the state, striated the meaning of sea (smooth space) through a special abstract machine produced by the social formations present in the dominant signifying regime. And this theme connected machinically to the construction state, to technocracy and produced Aquapolis as its most condensed articulation. Tada Osamu describes Aquapolis as both a symbol and incarnation of the Japanese state and its government35 but Aquapolis was something more than that: it was the State itself, its government apparatus and the technosocial formations of that apparatus reproduced as machine, migrated and installed in Okinawa as a grand, yet essentially futile production of Japanese sovereignty. It was the state and its network of cohorts in the technocratic capitalist economy that made Aquapolis what it was. And at both the level of enunciation and at the level of technical operations, Aquapolis was the Japanese state and its business: its official name, Okinawa Kokusai Kaiyō Hakurankai Seifushutten Kaijō Shisetsu, was translated into English in Expo 75 literature as Floating Pavilion of the Government of Japan. Every nut and bolt, every measurement, construction and operating standard had been set and administered to Aquapolis by the state apparatus itself: the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, the Ministry of Construction. All visitors to the structure received certificates of Aquapolitan citizenship. There, off the beach at Motobu, Aquapolis striated the sea with furrows of the Japanese state and its connections to technology, capital, modes of production and futures, and with the fictions of Japanese rule returned to the archipelago.

Expo 75 closed on January 18, 1976. It then metabolized into Ocean Expo Park, anational commemorative site and tourist destination offering exhibits such as the Tropical Dream Center, the Tropical and Subtropical Arboretum, the Native Okinawa Villages, Emerald Beach and the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium.

Ocean Expo Park

Some of the pavilions fromExpo 75 remain, but Aquapolis no longer floats on the sea. It was towed off to Shanghai to be turned into scrap metal for an American company in 2000. Its architect, Kikutake Kiyonori, saw Aquapolis off to China and oblivion. “I wanted it to be used as a research base for an offshore oilfield or as a Black Current research station,” he said as the material manifestation of his 1970s’ visions of marine communities and the machinic heart of reversion headed toward the horizon. “Why did it have to end up a giant piece of scrap?”36

But by 2000, the work of Expo 75 and Aquapolis in the factory of Japanese sovereignty in Okinawa was done. The mask of Japanese control in the archipelago produced by Expo 75 had some success in convincing Japanese at least that the rule of Tokyo was real, and Expo 75 also proved to be an effective machine for production of Okinawa as an Hawai’ian-style resort destination and in reterritorializing Okinawa as part of the construction state. But in the end, the people who really needed to be convinced that the mask of sovereignty was in fact the actual face were not, for infrastructure, resorts, mutations of landscape and place, and construction failed to conceal the real visage of power from Okinawans themselves. Just as United States’ objections to the proposed theme of the Okinawa Pavilion at Expo 75 determined how that building and its exhibits finally materialized, so too United States’ permissions, prohibitions, needs and global strategy continued and still continue to dominate what and how Okinawa is today. Japan’s sovereignty in the Ryūkyū Islands is little more than a stage prop for the performances of the American war machine against which Okinawans continue to fight as they did not fight against Expo 75 and its machinic productions.

Vivian Blaxell researches the spatial, cultural and social practices of Japanese colonialism. She has taught Japanese and Asian politics and history at universities in the United States, Japan, China, Australia and Turkey. Currently an independent scholar, she runs a global literacy consultancy in Australia. She may be contacted at [email protected].

She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Vivian Blaxell, “Preparing Okinawa for Reversion to Japan: The Okinawa International Ocean Exposition of 1975, the US Military and the Construction State,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 29-2-10, July 19, 2010.

Notes

1 McCormack, Gavan. 2010. “The Travails of a Client State: An Okinawan Angle on the 50th Anniversary of the US-Japan Security Treaty,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 10-3-10, March 8. For other discussions of the continued dominance of the United States in Okinawa after 1972, see for example, Yoshio Shimoji, “The Futenma Base and the U.S.-Japan Controversy: an Okinawan perspective,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 18-5-10, May 3, 2010. Steve Rabson, “’Secret’ 1965 Memo Reveals Plans to Keep U.S. Bases and Nuclear Weapons Options in Okinawa After Reversion,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 5-1-10, February 1, 2010.

2 1973. “Okinawa kokusai kaiyō hakurankai – Expo 75” Tsuchi to kiso, Vol. 21, No, 4, pp. 87-89. The Japanese Geotechnical Society.

3 In Robert W. Rydell. 1985. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

4 Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age. New York: Hill and Wang, p. 209.

5 See Ley, D., Olds, K. 1988. “Landscape as spectacle: World’s fairs and the culture of heroic consumption.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 191 – 212.

6 For just one example, see Yamaji Katsuhiko, “Takushoku hakurankai to ‘teikoku hantonai no shojinshu’” [The Colonial Exposition and “Peoples of the Empire”], Kansai Gakuin Daigaku Shakaigakubu Kiyō, Vol. 97, 2004, pp. 25-40.

7 Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October, Vol. 59, Winter, p. 4.

8 Tada Osamu. 2004. Okinawa imeeji no tanjō: aoiumi no karuchuraru sutadiizu [Formation of the Okinawa Image: Cultural Studies of the Blue Sea], Tokyo: Tōyō Keizai Shinpōsha.

9 Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum, p. 367.

10 Kikutake Kiyonori. 1973. “Kaiyō kaihatsu” [Ocean Development], Kaiyō kaihatsu no mondai: Kenchiku nenpō 1973, Architectural Institute of Japan, p. 543.

11 Figal, Gerald. 2008. “Between War and Tropics: Heritage Tourism in Postwar Okinawa” The Public Historian, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 91-94.

12 Tada Osamu, op. cit., pp. 1-4.

13 This data is taken from the official Nippon Foundation Library website. Accessed October 20, 2009. The Nippon Foundation was established as the Sasakawa Foundation in 1962 by Sasakawa Ryoichi who also founded the Japan Motorboat Racing Association and the Japan Shipbuilding Industry Association.

14 On Sasakawa, see for example, Richard J. Samuels. 2005. Machiavelli’s Children: Leaders and Their Legacies in Italy and Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, and Karoline Postel-Vinay and Mark Selden. 2010. “History on Trial: French Nippon Foundation Sues Scholar for Libel to Protect the Honor of Sasakawa Ryōichi,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 17-4-10, April 26.

15 Tada Osamu, op. cit., p. 48.

16 Debord, Guy. 2002. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Ken Knapp, p. 2. Available as a PDF file here. Accessed and downloaded October 25, 2009.,

17 Accessed October 21, 2009.

18 Tada Osamu, op. cit., pp. 107-109.

19 Quoted in Tada Osamu, op. cit., p. 105.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid, pp. 72-75.

22 Figal, Gerald, op.cit, pp. 91-94.

23 For a full discussion of the colonial folding of Shuri Castle into a Japanese topos, see Tze M. Loo. 2009. “Shuri Castle’s Other History: Architecture and Empire in Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 41-1-09, October 12.

24 Accessed March 2, 2010.

25 Pernice, Raffaele. 2004. “Metabolism Reconsidered: Its Role in the Architectural Context of the World” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, Vol. 3, No. 2, p. 359.

26 See this link.

27 See this link. Accessed March 16, 2010.

28 Raisbeck, Peter. 2002. “Marine and Underwater Cities 1960-1975” ADDITIONS to architectural history XIXth conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand, Brisbane: SAHANZ, p. 1.

29 See this link. Accessed October 19, 2009.

30 Kikutake Kiyonori. 1977. “Kaiyō wo ningenkyojū kūkan to shite toraeru hitsuyōsei” [The necessity of taking the sea as human habitat] Kenchiku Zasshi, Vol. 92, No. 1126, p. 35.

31 Hoshino Mamoru, Ishida Minoru, Ninomiya Katsuya, and Nishitani Harumitsu. 1976. “A Study of Characteristics of World-First Floating City Aquapolis” A paper prepared for presentation at the Eighth Annual Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, May 3-6, 1976.

32 Kikutake Kiyonori. 1974. “Kaiyōkaihatsu to Akuaporisu” [Ocean development and Aquapolis], Kenchiku Zasshi, Vol. 89, No. 1084, pp. 785.

33 Kikutake Kiyonori. 1975. “Akuaporisu keikakujō no shomondai” [Various problems regarding the design of Aquapolis] Kenchiku Zasshi, Vol. 90, No. 1097, p. 798.

34 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p. 425.

35 Tada Osamu, op. cit., p. 82.

36 Okinawa Taimzu, October 24, 2000.