South Korean Soap Operas Win Large Audiences Throughout Asia – and beyond

By Vanessa Hua

Seoul — Patients in hospital gowns crowded in with their IV poles. Visitors pressed against glass doors to watch. The crew hovered with lights, camera and microphone.

“Ready … cue,” the director barked, then filmed the scene of a young widow undergoing tests to give a kidney to her mother, who had abandoned her as a child.

![]()

1. On the set of “Be Strong, Geum-Soon,” cast and crew enact a story abt a young widow having tests to give a kidney to her mother. All photos by Vanessa Hua.

On location at Chung Ang University Hospital, the crew from “Be Strong, Geum-Soon” on the MBC network was filming the latest installment of a hot South Korean export: television dramas. Like the ardent horde at the hospital, millions of fans across Asia began tuning to South Korean soap operas in the late 1990s. Now, the dramas are winning over devotees in the United States.

As Americans flee network television in droves, Korean dramas are grabbing audience share. In the Bay Area, “Dae Jang Geum,” or “Jewel in the Palace,” aired this spring, dubbed in Mandarin on the Chinese-language KTSF. For the finale, more than 100,000 fans tuned in, handing the show higher ratings than ABC’s “Extreme Makeover,” the WB’s “Starlet” or PBS’ “Live From Lincoln Center” in that time slot.

The “Korean wave” of pop culture – known in South Korea as hallyu – is a point of national pride, helping introduce the country to the world and breaking down historical grudges with its neighbors. The soaps have also boosted the popularity of South Korean movies and singing acts.

Business leaders are betting on the wave to sell other products, and the government is promoting the trend to attract tourists. Travel agencies in California and across Asia offer package tours of filming sites, which government figures show attracted 200,000 visitors in 2003. Last year, exports of South Korean programs – mostly dramas – totaled $71.4 million, up 70 percent over 2003, according to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

South Korean dramas arose when the country began deregulating its economy in the wake of the 1996 Asian financial crisis. As entrepreneurs remade the entertainment industry, academics say, creativity blossomed in the arts.

Along with television dramas, South Korean movies are gaining recognition in the United States. The gritty thriller “Old Boy” earned the 2004 Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. It played at the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival earlier this year, along with other South Korean movies now popular on the art-house circuit.

The television dramas often start in the childhood of the main characters, who face love triangles, deadly disease, family intrigue, class differences and other obstacles. Most last 20 or 30 episodes, instead of enduring the endless plot twists of U.S. soaps. They tend to have less violence and sex and to emphasize longing and delicate flirtation culminating in a kiss.

In South Korea, fans can get their fix of popular shows twice a week, often on consecutive weeknights, and episodes are re-run on weekends. Viewers can also download episodes from the Web, and show producers monitor online fan postings, which can influence the plots.

“Koreans are the No. 1 drama lovers in the world,” Lee Byung Hoon, producer of the popular historical epic “Jewel in the Palace,” said over a green tea shake at a Seoul cafe favored by politicians. “Korea is surrounded by powerful neighbors. Throughout history, (we) have suffered and endured. Koreans keep hope inside and never give up.”

Episodes of “Jewel in the Palace” include an evil court lady’s plot to hide a bad luck charm in the kitchen to turn the queen’s unborn child into a boy; a competition on how to cook whale meat; and a doctor using his acupuncture kit to save a woman who ate poisoned berries.

Produced for $15 million, the tale of an orphaned kitchen cook who went on to become the king’s first female physician 500 years ago has pulled in $40 million worldwide since it first aired in 2003. After reaching as many as 57 percent of viewers in South Korea, the series spawned a theme park and restaurants in Hong Kong that serve dishes featured on the show.

At the Korea National Tourism Organization in downtown Seoul, a new team of five marketers is selling the Korean wave, organizing events for overseas fan clubs and appointing actors as “tourism ambassadors.” Last month, the government launched the website www.hellohallyu.com, which lists information on celebrities, television dramas, movies and filming locales – in English, Korean and Japanese.

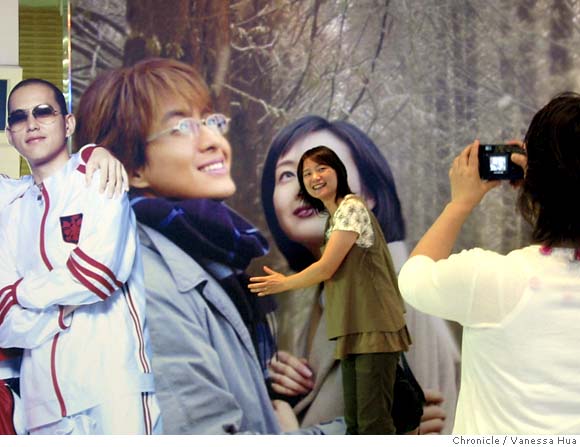

In the Korean Entertainment Hall of Fame, Midori Mizoguchi and Yumi Yamada, two sisters on vacation from Japan, giggled and took turns posing in front of a huge photo of Bae Yong Joon, the star of the mega-hit “Winter Sonata.” His sensitive look is replicated on billboards, notebooks, knit socks and other products throughout Asia.

2 . Midori Mizoguchi, a Japanese tourist, photographs sister Yumi Yamada with a Korean soap opera star. Mizoguchi, 36, a hairdresser, said her clients talk about nothing but the Korean stars.

“I thought (South Korea) was a very inflexible or constrained society,” she said. “But I find the people kind and enjoyable.”

Though popular culture naturally circulates among neighboring countries, that flow was disrupted in East Asia for decades after World War II. Bitterness among other Asian countries over Japan’s invasions hampered cultural exchange, and China, isolated under communist rule, cut off cultural influx from the rest of the world. Only in 1998 – more than 50 years after the Japanese occupation ended – did South Korea gradually lift its ban on cultural imports from Japan.

Greater exchange is likely ahead. “Once that is achieved, people who live in the region are able to gain a better understanding of how other parts of their region live and think,” said Michael Kim, an assistant professor of Korean Studies at Yonsei University in Seoul.

Su-jin Chun, 28, television columnist for the English-language edition of JoongAng Daily, one of South Korea’s biggest newspapers, cautioned that the world portrayed on Korean soaps reflects only a part of society.

“Still, it’s good that it’s hit it big,” she said.

South Korean dramas air in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Chicago, New York and Washington, D.C., and can be seen nationally in the US on cable channel AZN Television.

San Bruno’s Yesasia.com sells 20,000 to 30,000 English-subtitled Korean dramas every month, a figure it says is steadily growing. In the first six months of this year, the retailer sold more Korean dramas than in all of 2004.

In Hawaii, the Honolulu Advertiser prints synopses of the shows, which are broadcast there subtitled in English. The University of Hawaii held a conference last year on how South Korean dramas have influenced pop culture worldwide.

The Internet also abounds with bulletin boards, where fans from different countries discuss what happened and what they missed, and can view English-subtitled video clips they’ve made.

“I LOVE this drama,” writes user “clockworkhorror” in a bulletin board devoted to South Korean soaps available in California.

The fan, who describes herself as a “Hispanic girl who likes to watch Korean/Japanese shows,” was writing about “My Lovely Sam-soon,” South Korea’s version of “Bridget Jones.”

“Kim Sun Ah is great. I’m glad she isn’t the typical leading lady. And Hyun Bin’s acting has improved a lot. I can see why it’s kicking butt in the ratings!”

In the Bay Area, South Korean soaps attract fans of both sexes and various ages and ethnicities.

Cecilia Chang watched “Jewel in the Palace” with her husband, Dan, who praised the show in a column for Sing Tao, one of the Bay Area’s largest Chinese-language dailies.

“This is a gentle, feminine woman who is upholding her principles and beliefs, without alienating her family and friends,” said Chang, 54, of Fremont, describing the heroine. “She has all the virtues of a woman brought up in Confucian society.”

Melissa Lo, 25, shares their love of the series.

“I was almost dreaming about it, every day anticipating the next episode, ” said Lo, who is Chinese American, adding that she often discussed the show with her mother. “I can’t think of a single American show that has that sort of pull for me.”

“My mom said, ‘Who knew Koreans were so refined and sophisticated?’ ” the UC Berkeley graduate added. “She thought they were copycats of Chinese people.”

Kevin Roe, 51, a San Jose attorney, appreciates the rich photography, character development and emotionally interesting stories of South Korean dramas.

“Korea was sort of overlooked before,” Roe said, “but now it’s worth investigating.”

Vanessa Hua is a staff writer for The San Francisco Chronicle. This article appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle on August 28, 2005 and at Japan Focus on August 29, 2005.