Shuri Castle’s Other History: Architecture and Empire in Okinawa

Tze M. Loo

The Ryūkyū Kingdom Festival (Ryūkyū ōchō matsuri), organized and sponsored by the Shuri Promotion Association (Shuri shinkōkai), is a fixture on Okinawa Prefecture’s cultural and tourist calendar.

2008 Shuri Castle Festival poster

This one-day festival is one part of the larger Shuri Castle Festival (Shurijō sai); together, they celebrate the grandeur of the Ryūkyū Kingdom and its court traditions as a pure cultural past for the prefecture.1 Of pivotal importance to these events is Shuri Castle itself. Not merely the stage on which festivities unfold, Shuri Castle – with its vermillion architecture epitomized by its main hall (seiden) and Shurei Gate (Shurei mon), and its high, imposing ishigaki stone walls – is cast as the very heart of Ryūkyūan culture. While this representation of the castle celebrates local culture, it is difficult to ignore the role it plays in Japan’s continuing colonization of Okinawa. By suggesting that Ryūkyūan culture not only exists, but flourishes within the framework of the Japanese nation state, this representation plays an important part in a narrative that obfuscates the rupture of Japanese colonization of the Ryūkyū Kingdom and naturalizes Okinawa’s inclusion into the modern Japanese nation state.2

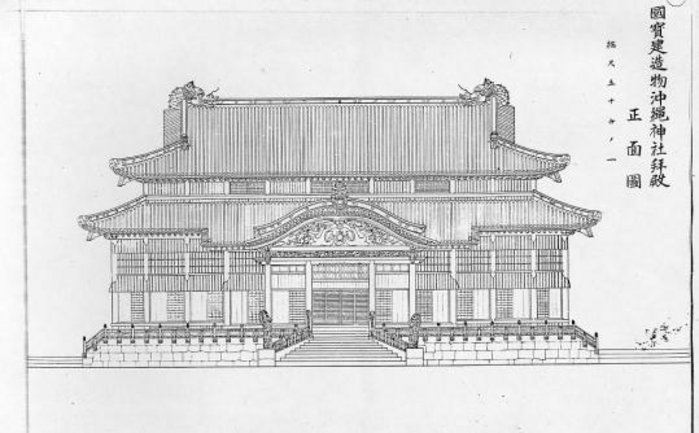

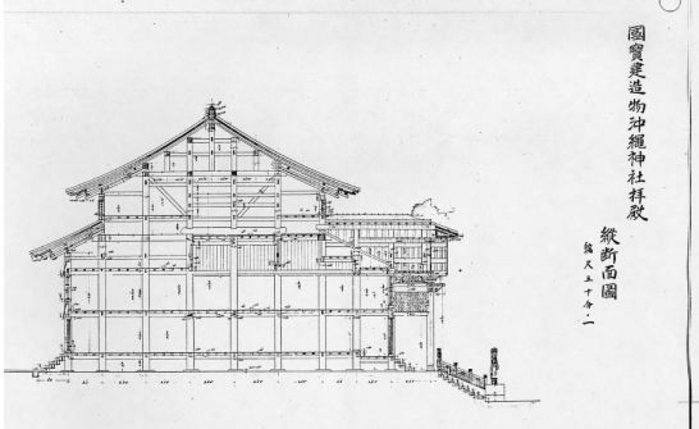

Nowhere is the assimilative nature of cultural valuation more stark than in the Japanese state’s 1925 designation of Shuri Castle’s main hall as a “national treasure” (kokuhō) of Japan. This designation is often lauded in the postwar as a sign of the Japanese state’s early recognition of the value of Ryūkyūan culture, but it also deftly transformed a marker of a prior independence into a marker of inclusion. The official text explaining the designation reads:

This is the main hall of the former Shuri Castle, and it is the Ryūkyū’s most important and largest piece of architecture … The current building was built in the 14th year of Kyōhō (1730) and underwent substantial repairs in the 3rd year of Kōka (1837). It has a very large, multilayered hip-and-gabled roof, a step canopy (kōhai) in the front [and demonstrates] unique Ryūkyūan form and techniques. Even though its large pillars and the decorative feature (fun) of the bargeboard (karahafū) resemble Chinese style (kan shiki), the frog-leg strut (kaerumata) and dragon carvings below the step canopy’s bargeboard carries the trace (obi) of the style of our Momoyama period [and is] extremely novel artisanship.3

Assimilation is performed in several ways here. First, Shuri Castle’s history is told in terms of Japanese reign names, mapping the castle’s history onto a regime of Japanese temporality even though the Ryūkyū Kingdom at this time was, for all intents and purposes, an independent political entity. Second, while the designation recognizes the uniqueness of Ryūkyūan form and techniques and even acknowledges its resonance with continental styles, the text – in the final analysis – folds these features into a narrative of Japanese architectural history. By discovering in these Ryūkyūan/continental features the “trace” of “our Momoyama” style, the designation skillfully sublimates any Ryūkyūan uniqueness into a larger, encompassing, and original Japanese cultural universe, diffusing the critical potential in these markers of difference.

There was, however, another way in which this designation appropriated and assimilated Shuri Castle into the Japanese national imaginary. In order for Shuri Castle’s main hall to be designated a national treasure in 1925, it was converted into the worshipper’s hall of Okinawa Shrine. This completed the layout for Okinawa Shrine, and Shuri Castle spent the period 1925 to 1945 as “Okinawa Shrine,” a functioning node in the ideological universe of State Shinto, put into the service of the emperor-centered Japanese nation state. This transformation occurred in part because Japanese heritage preservation laws until 1932 stipulated that only Shinto shrine and Buddhist temple buildings could be designated “specially protected buildings” to receive state protection and funding as “national treasures.” The problem is that the argument that the castle’s conversion was necessary for its preservation was privileged, both at the time as well as in our present, such that Shuri Castle’s tenure as a Shinto shrine is overlooked and its significance downplayed. This article traces Shuri Castle’s other history, to tell the story of its transformation into Okinawa Shrine in order to reveal the nakedness of the violence of Japanese colonialism as it is embedded in Shuri Castle.

The Silence around Okinawa Shrine

People have generally expressed surprise when I’ve posed the question, “Did you know that Shuri Castle used to be Okinawa Shrine?” This is not entirely surprising considering that histories of the castle – including the castle’s “official history” as it is told at the Shurijō Castle Park – do not reference its past as Okinawa Shrine. What is curious, however, is that the castle’s history as Okinawa Shrine is not exactly the object of a concerted campaign of silencing and obfuscation, with references to it readily available in the historical record. For instance, in prewar official inventories of national treasures compiled by the Home Ministry (Naimushō) which list all designated buildings and objects, Shuri Castle’s main hall is listed as “the worshipper’s hall of Okinawa Shrine” (Okinawa jinja haiden).4 In a relatively recent compilation by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (Bunkachō) of national treasures lost to war and disaster in the prewar period, the entry for Shuri Castle’s main hall, razed to the ground as a result of American bombardment, was similarly listed as the worshipper’s hall.5 Thus as far as one version of the Japanese state’s official record is concerned, “Shuri Castle” does not actually exist in the period between 1925 and 1945, replaced instead by “Okinawa Shrine.”

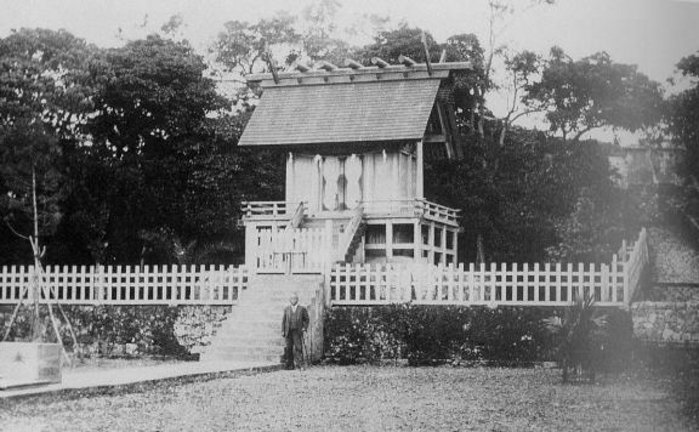

Two different treatments of a photograph in a recent volume about Okinawa demonstrate what is at stake. The photograph in question dates from the 1920s and shows Yamazaki Masatada, a medical professor from Kyushu in front of Okinawa Shrine’s main sanctuary (honden).

Yamazaki Masatada in front of Okinawa Shrine’s main sanctuary. From Nonomura Takeo, Natsukashiki Okinawa

In a comment on the photograph, Nonomura Takao writes:

Considering the situation at the time, there was no other method of rescue except for the main hall to take on the name of Okinawa Shrine’s worshipper’s hall, thereby receiving financial aid from the state in the form of a repair budget. This was a turnaround for a building that was destined to be demolished, and there was the great repair in the early Shōwa period. This ingenious plan (myōan) was thought up by Itō Chūta, and was seen to extraordinary success by Sakatani Ryōnoshin. [The castle] was saved as Okinawa Shrine. As the worshipper’s hall attached to the main sanctuary, Shuri Castle’s main hall sidestepped the big wave of the time.6

While all this is certainly true, this treatment deftly sublimates Shuri Castle’s becoming Okinawa Shrine into the larger aim of preserving the main hall and effectively dismisses the transformation of the castle into the shrine as a significant event in its own right. By privileging a narrative of preservation, the meaning of the Shuri Castle’s transformation into Okinawa Shrine is strait-jacketed into an argument in which the end (preservation) justifies the means.

The second treatment of this photo is in an essay discussing the role of old photographs in the restoration of Ryūkyūan architecture.7 While the author acknowledges that the photograph is one of the few which exist of the shrine, he notes that the photograph’s value lies in what it tells us of the area around the main sanctuary. He is interested in the information the photograph provides, but ignores the existence of the shrine itself. The castle’s tenure as a Shinto shrine is present, even acknowledged when it surfaces, and yet those who come into contact with it seem able to ignore its existence and its implications. What was the reality of Okinawa Shrine, and what were the conditions of its emergence?

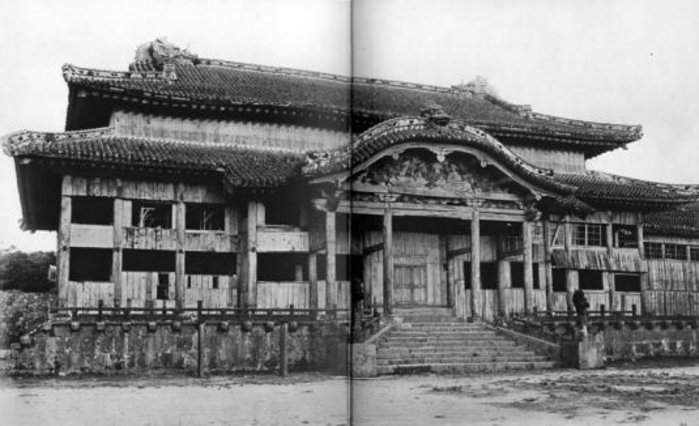

Shuri Castle in the early Meiji period

Until the early 15th century, the Ryūkyū Kingdom was divided into three competing power blocks, Hokuzan, Chūzan, and Nanzan. In 1429, Shō Hashi completed the unification of the kingdom and established Chuzan’s hegemony over the other centers. The seat of his power was Shuri Castle, which remained the kingdom’s political and sacerdotal center until 1879. Even before unification, the Ryūkyū Kingdom was already part of the Sinocentric world order as the lords of Hokuzan, Chūzan, and Nanzan sought political legitimacy and trading rights from the Ming emperor. Upon achieving unification, Shō Hashi received the Chinese court’s investiture as the “King of Ryūkyū” and the kingdom’s submission to the Chinese empire (while maintaining political autonomy) became a dominant factor in Ryūkyūan life. The tribute relation was not only political, but was also economically profitable and transformed kingdom into a prosperous linchpin in an “intra-Asia trade system” (Ajia ikinai kōei ken).8 The kingdom subscribed to Chinese influence in other ways too as Chinese Confucianism became the dominant framework that governed political, social and ethical life.9

In 1609, Tokugawa Japan’s southernmost fief, Satsuma, invaded the Ryūkyū Kingdom as it sought to appropriate the profits from the kingdom’s lucrative tribute trade. Satsuma could not impose its rule explicitly because it had to allow the kingdom to maintain an appearance of independence in order for that trade with China to continue. This resulted in the period of “dual tribute” – where the Ryūkyū Kingdom paid tribute to both China and Japan – which effectively reduced the kingdom to poverty.10 Despite its “non-explicit” overlordship, Satsuma’s invasion marked the beginning of Japan’s gradual colonization of the Ryūkyū Kingdom which culminated the Meiji state’s formal annexation in the 1870s. The Meiji state began this process in 1872 by unilaterally converting the kingdom into “Ryūkyū domain” (Ryūkyū han) and making Shō Tai (the last Ryūkyū king) into the “domain king” (han ō). In 1879, in what was termed the Ryūkyū Dispensation (Ryūkyū shobun), Meiji Japan annexed the Ryūkyū Kingdom, turning it into Japan’s southernmost prefecture, Okinawa.

The imposition of Japanese colonial rule meant the absorption of the kingdom into Japan’s administrative structure, a process which entailed the neutralization of the Ryūkyūan king as a symbol of independence and autonomy. When the Meiji state formally annexed the kingdom in 1879, it evicted Shō Tai from Shuri Castle and installed him as a member of the Japanese aristocracy in Tokyo. The seat of his power was not exempt from similarly radical change. Immediately after the annexation, the castle was converted into barracks for the Kumamoto Garrison (Kumamoto chindai bunkentai heiei), to become what Uemura Hideaki has called “Ryūkyū/Okinawa’s first foreign military base” in 1876.11 It suffered much damage in this conversion as it was a process of displacement which broke existing meanings and replaced them with new significations in both the physical and symbolic registers. Maps of Shuri Castle from the 1880s demonstrate the symbolic violence of this displacement in stark terms. The visual force in an 1893 map of the garrison, for instance, lies in its demonstration of the garrison’s complete takeover and redefinition of the site where even the buildings that were not in use were labeled “empty” (aki) or left shaded in the stripes as the building under use.12

Map of the Garrison. From Okinawa hontō torishirabe sho (1893)

This conversion of the castle’s space to new uses coincided with its destruction as a palace. During his visit in 1882, the traveler F.H.H. Guillemard noted that he thought that the main hall was “a holy of holies” but upon entering,

[a] more dismal sight could hardly have been imagined. We wandered through room after room, through corridors, reception halls, women’s apartments, through the servant’s quarters, through a perfect labyrinth of buildings, which were in such a state of indescribable dilapidation. The place could not have been inhabited for years. Every article of ornament had been removed; the paintings on the frieze – a favorite decoration with the Japanese and the Liu-kiuans have been torn down, or were invisible from dust and age … In all directions the woodwork had been torn away for firewood, and an occasional ray of light from above showed that the roof was in no better condition than the rest of the building. From these damp and dismal memorials of past Liu-kiuan greatness it was a relief to emerge on an open terrace on the summit of one of the great walls …13

For Guillemard, the castle, along with any greatness of civilization it marked, was a thing of the past. His observation that “the place could not have been inhabited for years” establishes the scale of the dilapidation, but also removes Shuri Castle even further from the present. The castle’s physical decline was tactile proof that the castle, and by extension, the Ryūkyū Kingdom itself, belonged to a different time, out of sync with the present of Meiji Japan. The castle became a double wound on the Okinawan landscape: its dilapidated presence reminded Okinawans that the Ryūkyū Kingdom was now a thing of the past, and that the eclipse of past greatness constituted the reality of the present.14

Shuri Castle’s physical decline created the conditions that broke the monopoly of meanings as a royal palace and opened it to redefinition, demonstrated in the calls for the palace site to be returned to the prefecture and converted into a site for popular pleasure. With the garrison’s departure in 1896, Okinawans called for the return of the castle to local civilian use. In 1899, Shuri ward petitioned the central government that notions of social progress called for the development leisure facilities in Shuri Ward for local use and to attract visitors from other prefectures, but Okinawa Prefecture had not achieved this.15 The solution, they proposed, lay with the castle site, arguing that it would be regrettable if the castle site – “the beauty of the Ryūkyū Kingdom for several hundreds of years” – was lost due to the current policy of abandonment.16 The petition asked the government to give the castle site and its buildings to Shuri ward without cost. Tokyo denied this request. Shuri ward tried again a year later, but this time requested the sale of the buildings which the Home Ministry approved but only allowed the use of the land for a thirty-year period.17 In 1909, Shuri ward petitioned the central government for the sale of the land and succeeded.18 In this way, ownership of Shuri Castle and its land was returned to the prefecture thirty years after Shō Tai’s eviction. Unfortunately the prefecture’s poor finances prevented any plans from coming to fruition. The castle’s main hall was so dilapidated that substantial and expensive restoration work would have been necessary simply to guarantee its structural integrity. Before the prefecture could raise the money, plans were already being made for the castle’s site to be used as the precincts of Okinawa Shrine.

Okinawa Shrine

Okinawa Prefecture first proposed the establishment of a prefectural shrine in April 1910 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Meiji emperor’s ascension.19 The proposed shrine would install Minamoto no Tametomo, Shunten, and Shō Tai as its resident deities, selected because they were important historical figures (san dai ijin) for Okinawa Prefecture who “made clear” (meiryō naru) Okinawa’s close relationship with mainland Japan.20 However, the idea was abandoned because of the death of the Meiji emperor in 1912. The motion to establish a prefectural shrine resurfaced in 1914 and 1915, but was denied on both occasions. The 1914 proposal, which suggested establishing the prefectural shrine within the grounds of Naminoue Shrine, was rejected as “impossible,” while the 1915 proposal was rejected because the deities the prefecture proposed – Amamiko and Shinireku, both of which were mythical figures in Ryūkyūan folk beliefs – were not recognized as part of the Shinto pantheon. The Home Ministry approved the establishment of “Okinawa Shrine” in March 31, 1923 for reasons that remain unclear and Shuri Castle was chosen as the site because it had been the historical center of Okinawa’s politics and was intimately connected with the prefecture’s “cultural enlightenment.”21

It is also possible that the Shuri Castle site was selected for financial reasons. The 1915 proposal budgeted 10,000 yen for developing a 3,443 tsubo site (approximately 2.8 acres) in Mawashi-cho, out of which 4,250 yen was slated for roads and other infrastructural costs.22 The proposed site was close to Shuri Castle, and maps from the period indicate a densely populated area interspersed with relatively large, aristocratic estates. That half the budget was set aside for infrastructure and other costs suggests that the site was quite costly to develop.23 By contrast, the Shuri Castle site was largely available, even though part of it was being used by the Shuri First Primary School and Shuri Girls’ Craft School. Construction began in September 1923, and the shrine’s main sanctuary was constructed behind the castle’s main hall. Given its poor condition, the decision was made to demolish the castle’s main hall so that a new worshipper’s hall could be built on its site in order to complete the spatial layout of Okinawa Shrine.

It is at this moment on the brink of physical erasure that Shuri Castle’s fortunes turned, almost entirely by chance. Kamakura Yoshitarō, a teacher who had spent some time in Okinawa, was visiting with friends in Tokyo one day in early 1924 when he noticed a newspaper article reporting the main hall’s demolition.24 Kamakura recounts that he rushed immediately to see Itō Chūta, the eminent architect with whom he was acquainted.25 Itō had never seen the castle itself, but knew that it was an important building.26 Itō in turn called on the Home Ministry and succeeded in halting the demolition.27 Concerned with securing both permanent protection for the main hall as well as official funding for its repair, Itō set out with Kamakura in the summer of 1924 on a month-long study trip to Okinawa.

In his account of his role in saving the main hall, Itō makes special mention of the main hall’s dilapidated condition.28 He notes that Okinawan authorities were keen to repair the building, even though the impoverished prefecture could not afford such a project. Unable to bear the loss of this “enormous building with deep pedigree,” efforts to raise funds for the building’s repairs continued even as the castle’s inner courtyard was slated to be given over to the new Okinawa Shrine. Itō’s account stoked the drama of the moment:

… it was a large sum of money, and there was no way to acquire it. With flowing tears, there was the realization that there was nothing else that could be done except to abandon (migoroshi suru) the main hall.29

From a photograph of the main hall, Itō said that he knew that it was a “representative masterpiece of Ryūkyūan architecture,” and after succeeding in halting the demolition and saving it from the “brink of death” (kyūshi ni isshō), Itō took it upon himself to see what he could do to further preserve the main hall. He writes,

I had to think of a concrete plan of how to save this almost dead (hinshi) patient. Before doing anything, there was the urgent task (kyūmu) of diagnosing the patient’s condition. One aspect of my research in Ryūkyū was this important mission.30

Itō’s assessment of his position was twofold: “Aside from welcoming me as a researcher of Ryūkyū, many Okinawan officials and civilians also welcomed me as the doctor (ishi) of Shuri Castle’s main hall.”31 Itō’s account conveys the urgency of his mission in which saving the castle took top priority, but his claim that he was welcomed by Okinawa officials and civilians adds an important dimension by implying the approval and support for his plans of Okinawans.

At the end of his study, Itō proposed that Shuri Castle’s main hall be used as the worshipper’s hall of Okinawa Shrine, thereby qualifying it for permanent state protection under the 1897 Old Shrines and Temples Preservation Act. The local newspaper carried an article with the headline: “Shuri Castle’s Preservation, The main hall becoming the worshipper’s hall of Okinawa Shrine through the Shrine and Temple Preservation Law after receiving recognition as a prefectural shrine and receiving the Home Ministry’s support is a good plan in Professor Itō’s opinion.”32 The article noted that this was the best way for the main hall to receive the repairs it badly needed, and thanks to “Professor Itō’s efforts (rō),” Okinawa’s famous site would now be preserved. A photograph of the repaired main hall testifies to the castle’s new doubled reality: two plaques hang at the entrance to the hall, mark it as both a “national treasure” and “worshipper’s hall”.

Detail, Showing “kokuhō” plaque on left, and “haiden” plaque on right.

The significance of Okinawa Shrine

As Itō’s commentary and the treatments of the photograph with Yamazaki that I began this essay with demonstrate, there is a strong desire to apprehend the moment of the castle’s main hall’s designation in terms of its preservation while ignoring its incorporation as part of Okinawa Shrine. Through the use of medical tropes and the drama of the situation, Itō successfully conveys that he was most concerned with the preservation the castle’s buildings. My intention is not to challenge this; Itō certainly had a deep and abiding love for buildings and spent his career committed to their preservation. However, to neglect the transformation of the main hall into the shrine’s worshipper’s hall surely misses the point at best. At worst, it marks the success of erasure in which the ideological machinations that enable Shuri Castle’s transformation into Okinawa Shrine are misrecognized as unimportant and regarded as irrelevant.33 To focus only on the preservation aspect of the 1925 designation echoes the constitutive logic in colonial power that seeks to obfuscate the arbitrariness and violence of its rule. Here, the violence of transforming Shuri Castle into Okinawa Shrine achieves the perfect cover behind the lofty goals of heritage preservation.

How then to read the moment of the 1925 designation, against the hegemonic desire to render it a triumph for heritage preservation, in order to recover Okinawa Shrine as a site of violence? The context of prewar State Shinto provides an important starting point. By becoming a Shinto shrine, Shuri Castle’s space was absorbed into the ideological universe of State Shinto and disciplined by its particular logic. Following the Council of State’s (Dajōkan) declaration of “the unity of government and rites” (saisei icchi) on March 13, 1869, the Meiji state promulgated a decree stating that Shinto shrines “constitute[d] the rites of the state” (jinja wa kokka no sōshi nari) on May 14, 1871.34 These measures defined Shinto as the national religion and established Shinto shrines as privileged spaces in the political life of the Japanese nation state. The role that the Grand Shrine of Ise played in the prewar era exemplifies the effect of this configuration: worshipping at the specific site of Ise Shrine was a mode of conduct for loyal Japanese imperial subjects to contribute to maintaining the health of the national polity.35

One of the most prolific theoreticians of the role of shrines in State Shinto and their relationship to Japanese national identity was none other than Itō Chūta, the “savior” of Shuri Castle’s main hall. Beginning with his involvement in the construction of Heian Shrine in Kyoto to commemorate the 1100th anniversary of transferring the capital to Kyoto, Itō designed and built a significant number of imperial Japan’s most important Shintō shrines.36 Professionally, Itō was the Home Ministry’s special consultant for constructing Shintō shrines from 1898, leading Maruyama Shigeru to observe that Itō’s official position in the bureaucracy was a way in which architecture was placed in the service of the nation state.37 Itō developed his ideas about Shintō shrines and their role in State Shinto in many articles, regarding shrines as the physical representations of the link between the imperial house and the Japanese nation state. He argued that while Shinto bore some similarities with Chinese Taoism or Central Asian religions, Shinto shrines were uniquely “Japanese” because they were for the worship of the Japanese imperial house and its imperial ancestors.38 Shinto shrines were, in other words, spaces that referenced the emperor and by extension, the imperial Japanese nation state.

Far from being simply a staging ground of Shinto, shrine buildings could channel individual emotion and feeling to focus on the worship of the imperial house.39 Itō considered “ideal” (risō) shrine architecture to fulfill two different aims.40 The first, material aim was functional: buildings and structures had to be easy to use in a practical sense. More importantly however, was shrine architecture’s second, spiritual dimension, which referred to their ability to manifest the spirit that repaid one’s ancestors for their gratitude, to return people’s hearts to the past, and to return to the fundamentals of the country.41 Itō’s ideas about the relationship of architecture and national identity, as well as his position on Shinto shrines as a specific site of Japanese national identity means that he was not a politically neutral actor when it came to Shinto shrines. Itō’s actions brought the central cultural symbol of the Ryūkyū Kingdom into State Shinto. This must in turn, at the very least, raise questions about Itō’s intentions in proposing the transformation of Shuri Castle’s main hall, and destabilize the comfortable narrative of salvation and preservation that Itō and others have cast the process as.

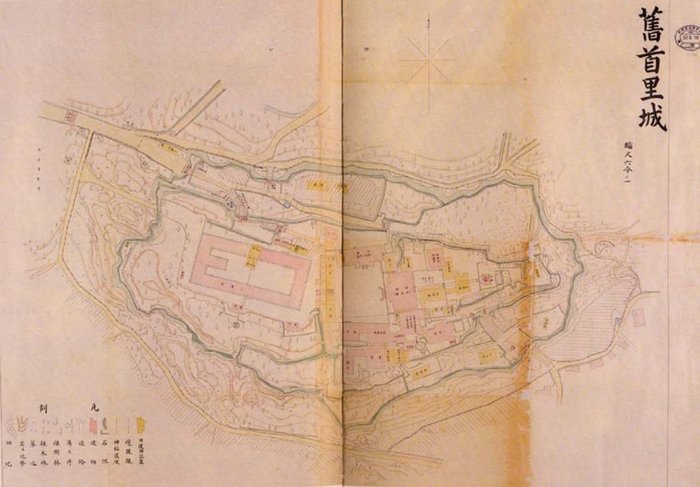

The Home Ministry regulated Shinto shrines strictly: not only who could establish a shrine and when, but also the very shape and content of shrine precincts. These regulations applied to the top-ranking national and government shrines as well as the prefectural and village shrines at the bottom of the shrine hierarchy.42 The Home Ministry listed seven structures that a shrine would have to include: the main sanctuary (honden), its surrounding fence, a torii, a worshipper’s hall (haiden), hall for food offerings (shinsenjo), temizuya, and shrine offices.43 These specifications constitute a set of rules by the Japanese state to govern the space of Shinto shrines. Each of the seven structures served a specific function and shrines without them were not recognized as shrines.44 The radical alteration to Shuri Castle’s space that resulted from its use as Okinawa Shrine is illustrated in a map titled “Old Shuri Castle” (Kyū Shurijō) which shows the castle’s original buildings overlaid with the new shrine’s buildings, including the seven structures that the Home Ministry deemed necessary.

Map of Okinawa Shrine precints, showing new and old buildings. Kyū Shurijō

Seen this way, it becomes clear that Shuri Castle’s transformation into a Shinto shrine was not simply about the transformation of its physical space, but rather the transposition of the castle into a spatial economy centered on the Japanese nation state.

This new configuration of space imposed a particular regime of bodily practices that regulated the conduct of those who entered it.

The main hall as Okinawa Shrine’s worshipper’s hall. From Shashinshu Okinawa

A torii at the northwest corner of the courtyard demarcated the shrine’s precincts, a line in the sand that marked the beginning of sacred space. In the courtyard, there was a small structure on the left, stone lanterns at the bottom of the stairs, an offering box at the entrance to the hall, and a braided rope above it. The small structure is the temizuya, where one washed one’s hands before approaching the worshipper’s hall. Going up the stairs, one stopped in front of the offering box and threw in a coin. One then performed the proper ritual combination of claps and bows to approach the gods deified in the main sanctuary. The braided rope above the offering box marked off the space it encloses as sacred, the hall and the area behind off limits to the profane masses.

Okinawa Shrine enshrined five deities: Minamoto no Tametomo, Shunten, Shō En, Shō Kei, and Shō Tai. As Torigoe has noted, the deification of Minamoto no Tametomo and his son Shunten emphasized Okinawa’s ethnic and blood proximity to mainland Japan and the legend of Tametomo and Shunten is worth recounting briefly here.45 After the Hōgen Rebellion, Tametomo – a direct descendent of the 56th emperor Seiwa – supposedly fled from the victorious Heike and escaped to the Ryūkyū Islands. There he fathered a son, Shunten, with the daughter of a local chief who rose to power as the island’s first king the 12th century. Scholars like Hagashionna Kanjun have shown that the Tametomo story (and Shunten’s reign, for that matter) have no documentary evidence, but note that they have a long history of circulation as legends.46 Scholars agree that the first mention of the legend is in the Buddhist monk Taichū’s Ryūkyū shintō ki (1605), but was established as part of the official record of the Ryūkyū Kingdom by Shō Shōken in his Chusan seikan (1650) and in turn popularized in Japan by Arai Hakuseki in his Nantō shi.47 The political potential of this narrative – that casts the Ryūkyū royal family and the institution of Ryūkyūan kingship as descendents of the Japanese imperial family – for assimilating Okinawa is obvious and it was reproduced frequently in novels, school textbooks, and studies of Okinawa history in the prewar period.48

What Torigoe does not discuss, however, is that the deification of the three Ryūkyūan kings was a similarly powerful, politically inclusionary move on Japan’s part. Shō En (r. 1470-1476) founded the second Shō dynasty; under his rule the Ryūkyū Kingdom shifted from government by the individual monarch to an institutionally based rule which contributed to its longevity.49 Shō Kei (r. 1713-1751) oversaw a cultural golden age in which the kingdom’s best-known Confucian intellectual Sai On flourished.50 Shō Tai’s reign saw the Ryūkyū Kingdom enter into formal Japanese control, cast in the prewar as opening the way for the modernization of Okinawa. Taken together these five deities speak to the appropriation of both the Ryūkyū Kingdom’s legendary past (Minamoto and Shunten) and its recorded history represented by the other three: Shō En founded the Second Shō Dynasty in which Shō Kei’s reign marked its high point, with Shō Tai marking its end. The deification of these five figures folds the beginning and the end of the Ryūkyū Kingdom’s history into the frame of State Shinto, and by extension, into the frame of the Japanese nation state and national imaginary.

How important or effective was the Okinawa Shrine? Did it register in the minds of Okinawan people as a site of State Shinto and what might this have meant to them? On the one hand, a 1936 report by Shuri city noted that “the number of worshippers increased every year, such that the sense of respect [for the national polity] has now gradually deepened.”51 On the other hand, Torigoe notes that worshippers were rarely seen at Okinawa Shrine, and he sees this as evidence of the forced nature of the Okinawa Shrine’s establishment and its disjuncture with what Okinawan popular religion.52 Okinawa Shrine’s relative unpopularity seems to be borne out by records in the Okinawaken jinja meisai cho, which lists the details of twelve shrines in Okinawa prefecture, including each shrine’s history, acreage, number of buildings, and the number of registered worshippers.53 Okinawa Shrine’s 4,914 ujiko households do not appear to be an insignificant number, especially when compared to Sueyoshi Shrine’s mere 160 ujiko households.54 However, Okinawa Shrine’s numbers pale in comparison to Yomochi Shrine’s 126,430 sūkeisha households.55 Given these numbers, it is likely that Okinawa Shrine was hardly the most popular and most-visited of shrines, demonstrating the distance that Okinawan people felt from State Shinto as a whole.

However, to assess Okinawa Shrine’s importance only in terms of the numbers of worshippers misses out on an important way in which spaces operate, and neglects how the particular space of the Shinto shrine functions. In particular, it misses how some spaces affect their environment simply by virtue of their presence, regardless of how resident populations feel about them. Overseas Shinto shrines (kaigai jinja), established in Japanese colonies (colonized Korea, Taiwan) as well as in locales with significant Japanese populations (Honolulu) illustrate this point. Overseas shrines were originally established for Japanese nationals in foreign lands as sites to connect ideologically and spiritually with the Japanese mainland, but many scholars have shown how overseas shrines also served as physical reminders of Japanese state power in the colonies for local populations.56 In addition to practices like compulsory visitations, which forced upon local populations a consciousness of the presence and function of the shrines, these shrines, often in geographically prominent sites (as in the case of Chosen Shrine, Taiwan Shrine, and Okinawa Shrine) were hard to ignore as sites on the landscape. A colonized population’s participation at shrines allows us to comment on the role these shrines played in people’s lives, but it is also important to pay attention to other reactions that local populations had to the space. These include non-participation at the shrines (except under duress) or their outright rejection of State Shinto, both of which do not necessarily render the shrines as unimportant or ineffective spaces.

Hildi Kang’s collection of oral histories from Korea under Japanese colonial rule includes accounts by people who talk about how they rejected State Shintō, but were forced to visit the shrines anyway. One of the most provocative vignettes however is a short account by a housewife who recalled: “The Pusan Shrine stood on top of the hill near the pier. We climbed up there many times, on holidays, but only for picnics. A beautiful view.” Even though this individual did not visit Pusan shrine to worship, she was clearly aware of how the space had been marked.57 Pusan Shrine existed as a place of worship even if people choose not to enter it or to use for other purposes, a space that local populations were forced to take into account, whether in confrontational ways or otherwise. In this sense, a lack of visitors or worshippers to Okinawa Shrine because of resistance to State Shinto or from indifference does not necessarily render the space ineffective. Okinawans’ failure to embrace the castle site as “Okinawa Shrine,” while signifying their lack of interest in participating in State Shinto, also reflects the success of that project in alienating the castle as a site of meaning for Okinawan people.

Conclusion

Let me return to the photograph of the shrine’s main sanctuary with which I began this essay and the question that it raised: what might account for this condition which allows for one aspect of the photograph to be noticed and not the other? In other words, what determines how historical materials and its “facts” are used? One possible explanation is that this is another effect of the Battle of Okinawa, which resulted in the death of between a quarter and a third of Okinawa’s population and the total destruction of its capital, Naha and much of the built environment of southern and central Okinawa. In addition to the loss of life, many of the materials that constitute a historical archive were lost. The result has been a paucity of materials about Okinawa’s history, and this exerts a certain pressure on materials that do exist. While the prefectural and village governments, tertiary institutions, and libraries in Okinawa are involved in an ongoing effort to collect and inventory what remains, the paucity of materials is a stark reality.58 In this context, the value of existing materials increases because they are (possibly) some of the only surviving traces of an “original” Okinawa. Alongside attempts to preserve what remains, there is a significant preoccupation with recovering the Okinawan past that was lost as a result of the war. This desire to recapture what was lost affects the treatment of historical materials from the prewar period, and creates a tension that the project to rebuild Shuri Castle illustrates.

Calls for the castle’s rebuilding, which began in earnest in the 1970s, cast the rebuilding as the recovery of an important piece of Ryūkyūan cultural heritage as well as the repayment of a debt the mainland owed Okinawa for its sacrifices in WWII.59 Advocates for the rebuilding appropriated then-prime minister Sato Eisaku’s proclamation that “Japan’s postwar will not be over until Okinawa reverts to the mainland” and turned it into the slogan “Okinawa’s postwar will not be over until Shuri Castle is rebuilt.” This clever adaptation intended to demonstrate how important the rebuilding was to Okinawans by inserting Shuri Castle into a larger discussion about Okinawa’s relationship with mainland Japan and making the castle a symbol of that process. The push for the rebuilding gained official sanction in 1982 in the Second Okinawa Development Plan. In 1984, Okinawa Prefecture released the Shuri Castle Park Basic Plan (Shurijō kōen kihon keikaku) and a committee under the auspices of the National Okinawa Commemorative Park Office took charge of Shuri Castle’s rebuilding.60

The committee’s first and most important task was the rebuilding of the castle’s main hall. According to one of the architects involved in the rebuilding, the committee had very little sense of what Shuri Castle looked like.61 The committee spent much of their first year gathering materials – including Kamakura Yoshitarō’s photographs and notes, and Tanabe Yasushi’s 1937 monograph Ryūkyū Kenchiku – and analyzing them in order to produce an accurate model of the main hall. A significant body of materials were the project reports from the castle’s/Okinawa Shrine’s 1932 restoration. Labeled “Worshipper’s Hall Okinawa Shrine” [figs. 7 and 8], these were extensive plans of the main/worshipper’s hall structural detail. As a way to express their intentions for the project, the committee coined the following motto: “To regenerate the main hall that had been rebuilt in 1712 and designated a national treasure in 1925.”62

Project reports from 1932 restoration of main hall/worshipper’s hall. Labeled “National Treasure Architecture Okinawa Shrine Worshipper’s Hall” from Kokuhō jūyō bunkazai kenchikubutsu zushū

Project reports from 1932 restoration of main hall/worshipper’s hall. Labeled “National Treasure Architecture Okinawa Shrine Worshipper’s Hall” from Kokuhō jūyō bunkazai kenchikubutsu zushū

This motto illustrates something of how present demands and desires to recover a lost past impacts the treatment of historical materials related to that past, for what would it mean to take this motto seriously? The committee intended the motto to signal their commitment to an authentic reconstruction of Shuri Castle – that is, the castle as it existed since its last rebuilding in 1712 after a fire, the same one recognized by the Japanese state as culturally valuable in 1925.63 However, the motto actually exceeds these intentions because it gestures at much more than the castle itself by invoking Japan’s colonial encounter with the Ryūkyū Kingdom. The period from 1712 to 1925 in Ryūkyū-Japan relations is dominated by the story of Japanese colonialism and the Ryūkyū Kingdom’s loss of autonomy, first through the system of dual tribute and then through formal Japanese annexation that culminated in 1879. The nature of this relationship left its trace on Shuri Castle too: because the Ryūkyū Kingdom did not have enough materials due to its increased impoverishment, the 1712 rebuilding could proceed only after Satsuma fief presented the kingdom with over 19,000 logs of wood. Many of materials the committee used from the Meiji period and after – especially Kamakura’s photographs [figs. 9 and 10] – show not a glorious architectural structure but are rather visual proof of the castle’s decay and destruction. The materials from the restoration of “Okinawa Shrine’s Worshipper’s Hall,” labeled as such, have the potential to raise difficult questions about the transformation of the castle’s space into a Shinto shrine and the political aims this served. One need only scratch the surface for the materials to tell a story of Japanese colonialism and its damage to Shuri Castle. What is so interesting about this motto is that if we were to take it seriously – that is, to engage with it in all its implications as a principle to produce knowledge about Shuri Castle – is that it invites attention to the violence and arbitrariness of Japanese colonialism, the very things that need to be managed if the narrative of Okinawa’s inclusion into the Japanese nation state is to be cast as a natural, seamless, and beneficial one.

Kamakura Yoshitarō’s photograph of Shuri Castle’s main hall. From Kamakura Yoshitarō, Okinawa Bunka no iho

Kamakura Yoshitarō’s photograph of Shuri Castle courtyard in front of main hall. From Kamakura Yoshitarō, Okinawa Bunka no iho

And yet, despite the motto’s potential to destabilize, the realities of the conditions of Shuri Castle’s existence in the period between 1712 and 1925 slip from the committee’s view as they made choices about what to recognize in the materials and what to ignore. Dominated by the desire to regenerate the castle, Shuri Castle’s multiple histories entered into a calculation where not all elements of the historical document are accorded equal value. Instead they are subject to a certain “political arithmetic” based on the demands of the present. The treatments of the photograph of Yamazaki and the shrine’s main sanctuary are examples of this: the photograph is valorized not for what it says about the shrine, but for the information that it provides of the area around it. This is, of course, a reasonable use of the photo, but in the process we see how Shuri Castle’s other history – which has the potential to destabilize comfortable narratives about the castle’s cultural value and raise questions about how the castle was used in schemes to naturalize Japanese colonialism – is quietly lost in the demands of the present.

Tze M. Loo is assistant professor of history at the University of Richmond. She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Tze M. Loo, “Shuri Castle’s Other History: Architecture and Empire in Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 41-1-09, October 12, 2009.

Notes

1 In 2005, the chairperson of the Shuri Castle Festival planning committee noted that “The Shuri Castle Festival is being fixed as the event that transmits (hasshin) the culture of the Ryūkyū Kingdom. [We would like] through colorful events, to deepen understanding towards Okinawan culture.” “Shurijō sai 10-gatsu 28-30 nichi ni kaisai kettei,” Ryūkyū shinpō, September 7, 2005.

2 This is similar to the observation that Laura Hein and Mark Selden make regarding the use of Shurei Gate on the 2000-yen banknote. They suggest that “by appropriating Shuri Castle as a symbol of Japanese nationhood suitable to grace the currency, Tokyo is again asserting control over Okinawans and subordinating them to the nation.” Laura Hein and Mark Selden (eds.), Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003) 12. Gerald Figal has recently shown how constructions of the Ryūkyūan past are part of a complicated recasting of Okinawa as a tourist destination. See his “Between War and Tropics: Heritage Tourism in Postwar Okinawa,” The Public Historian 30 (May 2008), 83-107.

3 “Shin shitei tokubetsu hogo kenzōbutsu gaisetsu,” Kenchiku zasshi, May 1925, No. 39, Vol. 470, 31.

4 Kuroita Katsumi, ed., Tokukenkokuhō mokuroku (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1927).

5 Bunkachō, Sensai tō ni yoru shōshitsu bunkazai: nijisseiki no bunkazai kakochō (Tokyo: Ebisukosho shuppan, 2003).

6 Nonomura Takao (ed.), Shashinshū Natsukashiki Okinawa: Yamazaki Masatada ra ga aruita Shōwa shoki no genfūkei (Naha: Ryūkyū shinpōsha, 2000), 14.

7 Taira Hiromu, “Ryūkyū kenchiku no fukkō to koshashin no yakuwari” in Nonomura Takao, Natsukashiki Okinawa: Yamazaki Masatada ra ga aruita Shōwa shōki no genfūkei (Naha: Ryūkyū shinpōsha, 2000), 44-47.

8 Hamashita Takeshi and Kawakatsu Heita (eds.), Ajia kōekiken to nihon kōgyōka, 1500-1900 (Tokyo: Riburo pōto, 1991) 9.

9 Gregory Smits has traced the way that Ryūkyūan court cultivated increasingly “Chinese” and Confucian representations and practice of kingship of the sage king, which included the decoupling of the Ryūkyūan king’s power from its historical relationship with the powerful female priestesses in Ryūkyūan religion. Iyori Tsutomu has traced how the changes in the architecture of Shuri Castle’s main hall (specifically looking at the changes to the bargeboard above the main hall’s canopy) were part of this policy of suppression. Gregory Smits, “Ambiguous Bounderies: Redefining Royal Authority in the Kingdom of Ryukyu,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 60 (June 2000), 89-123; Iyori Tsutomu, “Ryūkyū ōken no basho: Shurijō seiden karahafu no tanjō to sono kaishu ni tsuite,” Kenchikushi gaku 31 (1998), 4-6

10 George Kerr suggests that the Ryūkyū Kingdom saw its income reduced by more than half, from 200,000 koku to 80,000. George H. Kerr, Okinawa: The History of an Island People: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1975), 179.

11 Hideaki Uemura, “The Colonial Annexation of Okinawa and the Logic of International Law: The formation of an ‘indigenous people’ in East Asia,” Japanese Studies 23 (2003), 120.

12 Okinawa ken (ed.), Okinawa hontō torishirabe sho meiji 26-nen, 1893.

13 F. H. H. Guillemard, The Cruise of the Marchesa to Kamschtka and New Guinea. With notices of Formosa, Liu-kiu, and various islands of the Malay Archipelago (London: John Murray, 1886), 58-59. Italics are mine.

14 This is perhaps not dissimilar form Orhan Pamuk’s exploration of the the effect of Ottoman ruins as reminders of past greatness on Turks today and the melancholy (hüzün) that results from it. Orhan Pamuk, Istanbul Memories of the City (New York: Knopf, 2006).

15 “Kyū Shurijōseki nami kenbutsu haraisage seigan no gi nitsuki ikensho” in Maehira Bōkei, “Kindai no Shurijō,” in Yomigaeru Shurijō: rekishi to fukugen Shurijō fukugen kinenshi (Naha: Shurijō fukugen kiseikai, 1993), 276-277.

16 “We would like to use this land as a park, turn the buildings into a museum, establish an entertainment area displaying hundreds of things beginning with tropical plants that are different from that of other prefectures, and historical treasures that are different from places whose development is different. This is in planning for public leisure, but at the same time, to encourage economic development through foreigners who visit, to start the development of [our] civilization.” “Kyu Shurijōseki nami kenbutsu haraisage seigan no gi nitsuki ikensho.”

17 “Kanyūchi kariuke oyobi kenbutsu kaishū no ken” in Ryūkyū shinpō, January 29, 1903. Also in Maehira, “Kindai no Shurijō,”277. See also “Shurijō jisho taifu nami kenbutsu haraisage no ken,” Rikugun sho dainikki meiji 38-nen, National Archives of Japan.

18 The land was sold for 1514 yen 15 sen. Maehira, “Kindai no Shurijō,” 278.

19 The information in this paragraph summarizes parts of Torigoe Kenzaburō’s Ryūkyū shūkyōshi no kenkyū (Tokyo: Kadokawa shoten, 1965), esp. 655-660.

20 “Kensha sonsha kensetsu riyūsho” in Torigoe Kenzaburō, Ryūkyū shukyoshi no kenkyū, 655. For the Minamoto’s relationship to the Ryūkyū islands, see George H. Kerr, Okinawa: The History of an Island People: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1975).

21 Jinja kyōkai zasshi, 22:5 (1923), 34. Okinawa ken jinja meisai chō, Okinawa Prefectural Library collection, publication date unknown.

22 Figures are given in Torigoe, Ryūkyū shūkyōshi no kenkyū, 659. He set the costs for the construction of the buildings at 5000 yen.

23 Torigoe notes that the prefecture’s attempt to raise funds from among Okinawans for the shrine in 1914 failed. He took this as an indicator of the shallowness of Okinawans’ civilization and cultural development (mindō), as well as a lack of interest in establishing the prefectural shrine. Torigoe, Ryūkyū shūkyōshi no kenkyū, 659.

24 Kamakura Yoshitarō, Okinawa bunka no ihō (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1982), 61. Kamakura does not note the title of the article he saw, but it was likely “Okinawa ōchō no Shurijō wo torikowashi okinawa jinja konryū,” Kagoshima mainichi shimbun, 25 March 1924. See also Itō Chūta, “Ryūkyū kikō,” in Kengaku kikō (Tokyo: Ryūgin sha, 1936), 31.

25 Kamakura’s account can be found in his Okinawa bunka no ihō (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1982).

26 Itō Chūta, “Ryūkyū kikō,” Kagaku chishiki 5 (1925), 31.

27 He achieved this with an emergency provisional designation under the 1919 Historic Sites, Places of Scenic Beauty, and Natural Monuments Preservation Law.

28 Itō, “Ryūkyū kikō,” 30.

29 Itō, “Ryūkyū kiko,” 31.

30 Itō, “Ryūkyū kikō,” 31.

31 Itō, “Ryūkyū kikō,” 31.

32 “Kensha no nintei wo etaru ato shajihozonhō ni yotte seiden wo okinawa jinja no haiden tonashi naimushō no iji ni yoru no ga tokusaku Itō hakushi no iken,” Ryūkyū Shinpō, 9 August 1924. The text of this article is reproduced in Yoshiike Fumie, “‘Firudo noto dai 22 kan ryukyi’ wo moto ni,” Masters thesis, Kyoto Institute of Technology, 2006, 177.

33 Ernesto Laclau’s observation that “[t]he ideological would not consist of the misrecognition of a positive essence, but exactly the opposite: it would consist of the non-recognition of the precarious nature of any positivity, of the impossibility of any ultimate suture” is theoretically instructive here. Ernesto Laclau, “The Impossibility of Society” in his New Reflections on the Revolution of Our Times (London: Verso, 1997), 92.

34 Wilbur Fridell, “The establishment of Shrine Shinto in Meiji Japan,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 2 (1975), 143. Helen Hardacre gives a slightly different translation of this phrase: “shrines as offering the rites of nation.” Hardacre, Shinto and the State 1868-1988, 97.

35 See for instance Hiroike Chikuro, Ise jingu to waga kokutai (Tokyo: Nichigetsusha, 1915).

36 These included the rebuilding of the Grand Shrine of Ise (1899 and 1909), Yahiko Shrine (Niigata, 1916), Meiji Shrine (1920), the expansion of Atami Shrine (1922), various parts of Yasukuni Shrine including the Yūshūkan, and the expansion of the Grand Shrine of Izumo. Of these, Ise, Meiji, and Yasukuni shrines stand out as especially privileged sites as the nexus of sacral, imperial, and state power that State Shintō enabled. In addition, Itō was also responsible for the design and construction of Shintō shrines in the Japanese empire’s colonial possessions, beginning with the Grand Shrine of Taiwan in 1901, but also Karafuto Shrine (1912), and the Grand Shrine of Chosen (1925).

37 Maruyama Shigeru, Nihon no kenchiku to shisō: Itō Chūta shoron (Tokyo: Dobun shoin, 1996), 121.

38 Itō, “Sekai kenchiku ni okeru nihon no shaji,”316-317

39 Itō Chūta, “Jinja kenchiku ni taisuru kōsatsu.”

40 Itō, “Jinja kenchiku ni taisuru kōsatsu,”17.

41 Itō, “Jinja kenchiku ni taisuru kōsatsu,”18-20.

42 These regulations start in the 1870s as the then Ministry of Doctrine (Kyobushō) issued regulations on the size the format of national and government shrines. See also Yamauchi Yasuaki, Jinja kenchiku (Tokyo: Jinja shinpōsha, 1972), 194-202 for some of these regulations.

43 Optional structures were also recommended. See Kodama Kuichi, Jinja gyōsei (Tokyo: Tokiwa shobō, 1934), 48.

44 Kodama, 54.

45 Torigoe, Ryūkyū shūkyōshi no kenkyū, 656. Also see note 37 above. George Kerr asks: “What better man to serve as a link between Okinawa and Japan than the legendary Minamoto Tametomo?” Kerr, Okinawa, 50.

46 Higashionna Kanjun, Ryūkyū no rekishi (Tokyo: Shibundō, 1957), Textbooks on Okinawan history today trace the beginnings of political history to the 13th century, and treat the period of Shunten’s reign as myth. See for instance Okinawaken kyoiku iinkai, Gaisetsu okinawa no rekishi to bunka (Naha: Okinawaken kyoiku iinkai, 2000).

47 Shō Shōken was a pro-Japan, Ryūkyūan statesman who is credited with being the earliest proponent of the theory of common Ryūkyūan and Japanese ancestry (nichi-ryū dōso ron) who was writing from within a Ryūkyū Kingdom subdued by Satsuma.

48 Kikuchi Yūhō, Ryūkyū to Tametomo (Tokyo: Bunrokudō shoten, 1908); Bungakusha, ed., Shōgaku sakubun zensho (Tokyo: Bungakusha, 1883); Shimabukuro Genichiro, Okinawa rekishi: densetsu hoi (Mawashison okinawaken: Shimabukuro genichiro, 1932).

49 Kerr, Okinawa, 102.

50 Gregory Smits, Visions of Ryūkyū: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999).

51 “Shuri shi kinen shi” in Naha shishi, Vol. 2, No. 2, 374. Kaji Yorihito has also found newspaper reports on Okinawa Shrine’s vibrant and busy shrine days. Kaji, 100-101.

52 Torigoe, 660

53 Okinawa Prefectural Library collection. All the figures that follow come from this material.

54 Ujiko refers to the group of people reside in an area around a shrine and who are registered with it. They are somewhat analogous to the notion of “parishioners” in terms of their relationship to the site of worship. Kokugakuin University’s online Shinto glossary defines ujiko this way: “Generally, a group from the land surrounding the areas dedicated to the belief in and worship of one shrine; or, the constituents of that group.”

55 Sūkeisha also refers to a shrine’s worshippers and is often used interchangeably with ujiko. However, strictly speaking, where ujiko refers to worshippers who live within the shrine’s defined district, sūkeisha refers to worshippers from outside that area. Yomochi Shrine’s numbers are those for “Okinawa prefecture as a whole” (Okinawa ken ka ichien). Yomochi Shrine was nevertheless a popular shrine and seems to have enjoyed support from the local population, in part because its resident deities were Ryūkyūan heroes, rather than deities from the Shinto pantheon. For more on Yomochi Shrine, see Kaji Yorihito, Okinawa no jinja (Naha: Okinawa bunko, 2000), 106-111. See also Kadena City’s website on the shrine,

56 See for example Mitsuko Nitta, Dairen jinjashi: aru kaigai jinja no shakaishi (Tokyo: Ofu, 1997), Koji Suga, Nihon tochika no kaigai jinja: chosen jingu taiwan jinja to saijin (Tokyo: Kobundo, 2004), and Akihito Aoi, Shokuminchi jinja to teikoku nihon (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2005). See also Minoru Tsushi’s Shinraku jinja: yasukuni shisō wo kangaeru tameni (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2003). For compulsory visitations, see Takeshi Komagome, “Shokuminchi ni okeru jinja sanpai,” in Seikatsu no naka shokuminchi shugi (Kyoto: Jinbunshoin, 2004), 105-129, Takeshi Komagome, Shokuminchi teikoku nihon no bunka togo (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1996).

57 Hildi Kang, Under the Black Umbrella: Voices from Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), esp. 114. See also pages 111-116.

58 The efforts of the Okinawa Prefecture Committee for the Promotion of Culture (Okinawaken bunka shinkōkai) and the Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education (Okinawaken kyōiku iinkai) to compile historical materials are exemplary. The latter’s Okinawaken shiryō (Okinawa Prefecture Historical Materials) series is an important collection of primary source material from the prewar. This is reflected in the mission of the Okinawa Prefectural Archives. In remarks commemorating the opening of the archives on August 1, 1995, the then director Miyagi Etsujirō commented that “because almost all [of Okinawa’s] prewar records were lost in this past war, it was a situation where we had to put postwar documents at the center [of our efforts].” Okinawa Prefectural Archives, ARCHIVES, vol. 1 (1996), 3. Photographs seem to receive special attention: Ryūkyū shinpō sha, ed., Mukashi okinawa: shashinshu (Naha: Ryūkyū shinpôsha, 1978), Shuritsu hawaidaigaku horeisokan henshu iinkai, Bōkyō okinawa shashinshū (Tokyo: Honpō shoseki, 1981), Okinawa terebi hoso kabushiki gaisha, ed., Yomigaeru senzen no okinawa: shashinshu (Urasoe: Okinawa shuppan, 1995), Okinawa terebi hoso kabushiki gaisha, ed., Yomigaeru senzen no okinawa: shashinshū (Urasoe: Okinawa shuppan, 1995).

59 Shurijō fukugen kisei kai kaihō 1, 1982, 3.

60 Okinawa kaihatsu chō, Okinawa shinkō kaihatsu keikaku. dai ni ji (Naha: Okinawa kaihatsu chō, 1982).

61 Kiyoshi Fukushima, “Shurijō fukugen sekkei ni tsuite no zakkan,” Okinawa bunka kenkyū 21 (1995), 40.

62 「1712年に再建され、1925年に国宝指定された正殿の復元を原則とする」, Fukushima, “Shurijō fukugen sekkei ni tsuite no zakkan,” 46.

63 Shuri Castle was rebuilt three times before after fires destroyed it in 1453, 1660, and 1709.