Japan’s New Blue Water Navy: A Four-year Indian Ocean mission recasts the Constitution and the US-Japan alliance

By the Asahi Shinbun

Translation by Eriko Osaki and Michael Penn

[This is the second of a two part series on the strategic and constitutional implications of Japan’s expansive naval role in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf. See Richard Tanter’s “Japan’s Indian Ocean Naval Deployment: Blue water militarization in a “normal country”.]

Part One: Postponing the Legal Issues and Sailing Rapidly

Facts about the Dispatch

According to its commanders, the unit which is now operating in the Indian Ocean is the thirteenth. So far, forty-seven ships, including convoy ships, supply ships, minesweepers, and others — with 9,260 sailors — have been dispatched. The ships sail from five bases in rotation, but two supply ships have been dispatched five times each.

“Prepare the warning shot!”

The command of the watch echoed on the bridge of the convoy ship Kurama, which was sailing in the Gulf of Oman near Iran, after 8 pm. Sailors in helmets and bulletproof vests hastily began to load pistol belts into machine guns on the deck, and the atmosphere of the ship became electric.

Radar had picked up a small craft of unidentified nationality approaching aft from the left at over 20 knots. The shadow of the ship was moving rapidly without answering signals of international radio. Everybody on the bridge suspected that it was a suicide terrorist vessel.

“If the ship approaches at this pace, we’ll have to shoot,” thought a commander of the first group, Honda Hirotaka (58). Next to him, Hirano Terutsugu (44), a ship commander, gasped, thinking, “This is going to be the first fire.”

It was about an hour after they spotted the ship. The shadow approached to about 500 meters, then sailed abreast of the convoy, and finally turned on its navigation lights. It turned out to be an Iranian police craft and danger was avoided. It was January 3rd, 2002, not long after they arrived in the Arabian Sea. The start was just like a “semi-combat zone.”

Commander Honda was sounded out on the dispatch after 9.11, shortly after Prime Minister Koizumi issued a seven article directive. Preparation started hastily.

“In any case, head your ships for the Indian Ocean. I’ll handle the situation before we reach there.” Just after he was told this by the commander of the convoy and left Japan with about 700 sailors, Kabul fell. The capital of Afghanistan had been controlled by the Islamic fundamentalist Taliban.

When they crossed the Straits of Malacca, the basic plan of the anti-terrorism law was finally decided in the cabinet, prescribing where and how to operate. However, details were uncertain, such as how to make contact with the U.S. military and where to buy fuel.

When they entered the Indian Ocean in the middle of November 2001, a U.S. military frigate requested refueling from them for the first time. However, the Defense Agency ordered them to “Wait.” Their explanation was that “the fuel they were carrying was not for the multinational force,” but for themselves, having been purchased from their defense expenses. The first refueling was thus unsuccessful.

The first duty of a commander in the field was to find a support base where they could get fuel. The Kurama visited nine locations in seven countries, including some along the Persian Gulf. Above the waters, hundreds of aircraft were flying out of three aircraft carriers with the intention of mopping up Al-Qaida remnants.

The long period of navigation in the Indian Ocean can be said to be “an uncertain battle” for the MSDF, which usually just repeats short-term training on Japan’s periphery. At first, the sailors were not told when they would return home.

In December 2001, a ship named Sawagiri reinforced the convoy transporting humanitarian supplies to Karachi, Pakistan. Many sailors assumed that they would be back before the end of the year, and some of them carried only several thousand yen, assuming that “we will not call at any port.” Their wallets were soon empty, and they asked their families to mail money from Japan.

As sailing drags on, human relations inside the narrow ships tend to get tense. When a baby was born in a family of a sailor, there was an announcement that “both mother and baby are in good condition,” and on Coming of Age Day, everybody congratulated young members. These things were done so as to “prevent divisions” among the crew.

Eventually the dispatch stretched over 152 days, into the next year. Petty Officer Usui Koichi (50) said, “It was more delightful to bring everyone back home safely than to actually accomplish our duty.”

It has been a full four years since the relief activities of the MSDF on the Indian Ocean began. Approximately nine thousand crew members and forty-seven ships have been dispatched in total. This series is going to describe their activities though the eyes of the dispatched crew members.

Part Two: Sticking to the Aegis Ships for Safety

The Aegis Ships

A U.S.-made combat ship provides air defense for the fleet. The ship is equipped with high-performance radar and computers, which enable it to locate and attack a target automatically, and to attack more than ten targets simultaneously with missiles with a range of more than 100 km. The MSDF now possesses four of these Aegis ships.

The northern Arabian Sea at dawn was blurred with a cloud of sand.

It was the early morning of March 20, 2003. Not many days had passed since the aerial bombing of Baghdad was launched. Takashima Hiroshi (53) of the fourth unit, a unit commander of the first ship, made an announcement to the unit members of three ships on the microphone of the Aegis ship Kirishima: “Our mission is clearly different from the attack of the American and British armies. Each of you is to calmly protect your allotted space.”

Recognizing that a number of navies were sailing toward the Persian Gulf, he felt it necessary to sweep away the crews’ worries about their involvement in the Iraq attack.

In December 2002, more than a year since they started operations in the Indian Ocean, the government decided to dispatch the Aegis destroyers. However, there was a gap between the perceptions of frontline U.S. forces and the Japanese government, the latter regarding the dispatch as “evidence of the Japan-U.S. alliance.”

Unit commander Takashima said, “The refueling activities were appreciated, but there weren’t any special remarks on the dispatch of the Aegis ships.”

The MSDF stressed security during ocean refueling. The two ships connected by a refueling pipe had to remain parallel to each other for long hours. Since the ships were vulnerable to attack during refueling, it was desirable to be guarded by the Aegis ships, whose radar could pick up targets a great distance away and whose computers had excellent data processing ability.

Shibata Masahiro (51), unit commander of the second ship, who led the Aegis destroyer Kongo, said that he felt “safe.” Every time a target on radar moves, a conventional convoy ship has to be maneuvered by an operator checking its direction and speed. On the Aegis ships, all of these operations are automated.” On a conventional convoy ship, no matter how skillful the sailors are, they still have some worries.”

In fact, a case was reported to the Defense Agency in which the guards on board observed a plane from one of the coastal nations, which was in a blind spot for the radar, flying over a conventional ship.

The dispatch of the Aegis ships was justified in the name of improvement of the sailors’ onboard quality of life, although it was initially delayed because the Aegis vessels’ ability to share information with the American Navy was not fully supported within the Japanese government.

“The air temperature was 42 degrees (C.), but 80 degrees on deck.” Sugimoto Masahiko (53), a unit commander of the third ship of the second unit, who had worked on a conventional ship during the summer, dropped an egg on the deck and took a picture, saying, “Just reporting numbers won’t help people understand the heat.”

Twenty or thirty minutes later, a sunny-side up egg was ready. This picture was probably used by the Defense Agency to gain the understanding of Komeito leaders, who had been hesitant about the dispatch of the Aegis ships.

Regarding the dispatch of the Aegis destroyers, Admiral Koda Yoji (55) reflected, “It would have been valuable if the Aegis ships had been dispatched right after 9.11.” His thought was based on his experience as a defense manager and the commander of a convoy ship.

DD Aegis Chokai, the last Aegis-equipped ship to be dispatched

At first, the U.S. military intended to deploy many Aegis ships on both the east and south coasts of Iraq, in addition to NATO AWACS aircraft (Airborne Warning and Control System), in order to prevent terrorism by aircraft.

If Japan’s Aegis ships had been dispatched to the Indian Ocean at that time, when the area was only lightly guarded, the dispatch might indeed have become “a symbol of the Japan-U.S. alliance.”

Why did they continue to deploy the Aegis ships? Admiral Koda answered, “Since the dispatch of the mine-sweeping unit to the Persian Gulf, our operations have become fairly well understood by the nation. However, we cannot say it is fully recognized. This time, there can be no failure at a time when the number of overseas operations is increasing.”

The Aegis ships carried out six missions to the Indian Ocean. There has been no dispatch of an Aegis ship since the Chokai was sent in November, 2005.

Part Three: Anti-terrorism: Shivering with Fear At Times; Exercises Daily

The Arms of the Convoy

A convoy ship is equipped with anti-aircraft missiles, explosive shells, and machine guns for air defense; anti-submarine torpedoes for defense against submarines; and anti-ship missiles. Under the anti-terrorism law, there are no limitations on the kinds of arms they may use.

The Arabian Sea looks dark green from the sky, and the tranquil water continues on to the horizon.

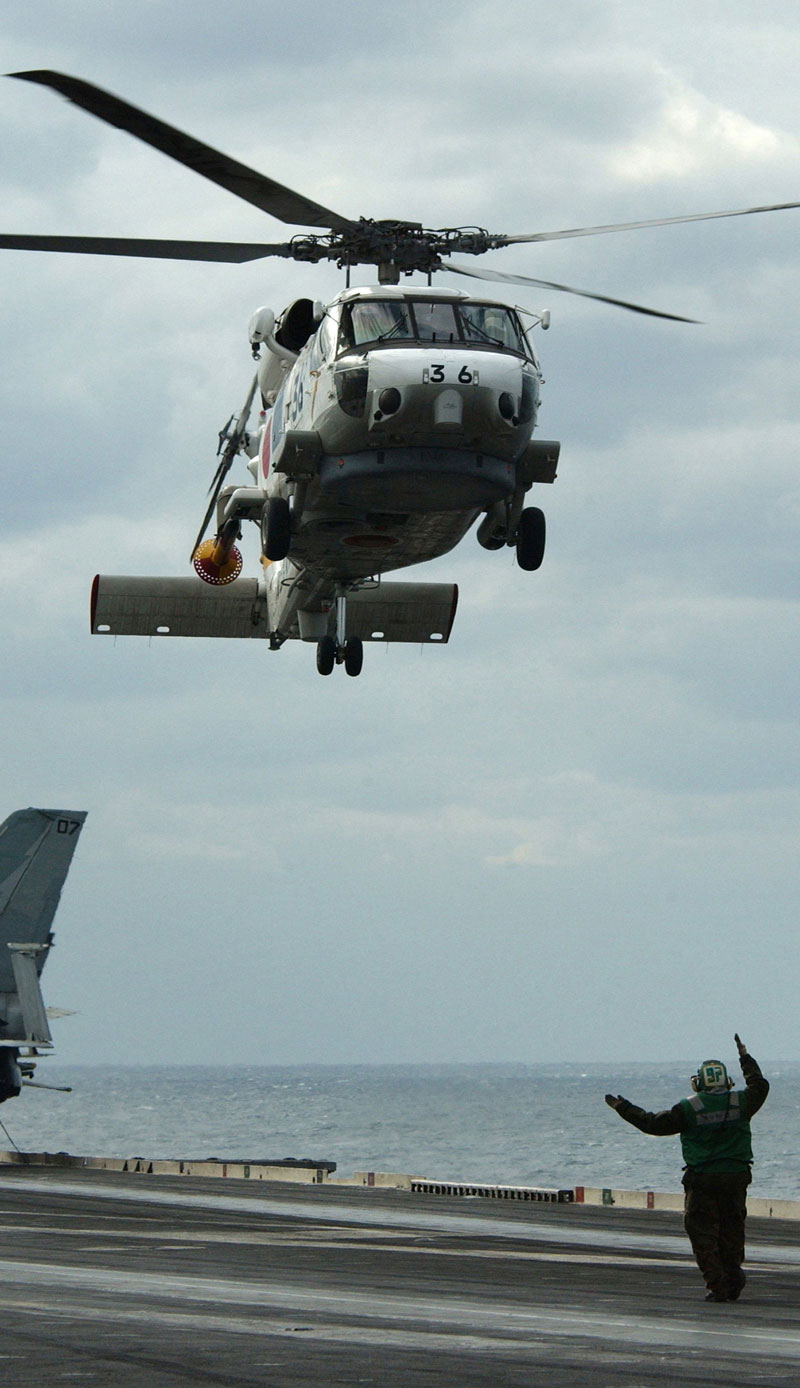

Aviation commander Murai Ryoichi (43) of the tenth unit, who returned home this January, was in charge of watching the water during refueling activities in a sea-borne helicopter. The Aegis ship Kirishima was at the front, followed by the refueling ship and a foreign ship parallel with each other. Another ship followed. The helicopter flew ten kilometers ahead at an altitude of about 150 meters.

Japanese SH-60J Seahawk landing

on the deck of the USS Kittyhawk

The detection range of the Aegis radar is over 200 kilometers, but small fishing boats and some others are hard to detect. He said, “Sometimes small targets emerge suddenly in the ocean and we were consistently moving.”

There were cases in which four sailors watched carefully and gave warnings on international radio when another ship moved into their path, and they even checked inside a suspicious ship using the guidelines and information of the U.S. military.

Other navies accompanied the refueling ships, but Captain Murai said, “I guess no other units guarded more carefully than Japan.”

On the water, exercises against suicide terrorism are repeated daily. “A craft of unidentified nationality is approaching at 60 degrees to the right of the ship, from 30 miles away.” A high-pitched warning vibrates in the ship. Sailors take their positions and a warship shell is sighted on the aircraft. There is a warning by radio, the shooting of signal bombs, warning fire…

In the Arabian Sea, where Operation Enduring Freedom is continuing, they have tried to learn from the attack on an American destroyer by terrorists on a small boat in Yemen in 2000. There are threats from both small planes that may plunge into a ship from a low altitude, and from small boats.

“Japanese are permitted to shoot only after thorough measures, even though a real attack could be completed in a matter of several seconds,” Fukuda Tatsuya (38), torpedo bombardier leader in charge of handling weapons, pointed out. If the object is an aircraft, shooting is not allowed until it approaches below approximately five kilometers, where it could be seen with the naked eye. That’s because they seek to avoid erroneous attacks by confirming carefully whether the opponent really plans to attack, according to the measures based on the antiterrorism law.

How dangerous is the operation in the Indian Ocean? Information which the U.S. provided other nations included one warning that specifically said that ships are targeted by terrorists.

Nishimura Takashi (42), a staff officer aboard a third unit ship, had a strange experience in the Straits of Hormuz in 2003. At midnight on a night with no moonlight, an object approaching at high speed from right forward was detected on the radar screen. He ordered the watch to spot it, but the light on the screen suddenly broke up into two. After passing by both sides of the convoy, they came together again. They couldn’t identify what it was. “They might have looked like one ship since they were close to each other. What would have happened if they had been terrorist ships?”

Sugimoto Masahiko (53) third ship Captain of the second unit encountered a drifting boat with about fifty people on board in 2002. He couldn’t just abandon them after finding them. He tried to make contact with them by sending a small boat. When the crew approached them, men who had been lying down suddenly got up.

“Damn! They may try to rob us of a boat.”

Captain Sugimoto told the Japanese boat crew to distance themselves from the drifting boat. If they were armed… In the end, they left it to the Canadian military which has the authority to board another vessel.

A number of units had liver-chilling experiences. However, no cases were reported in which units of the multinational forces were attacked by terrorists. “It has been three and a half years since launching the mission, and we’re now getting used to the field.”

In June 2005 the unit under the anti-terrorism law was reduced from three ships to two.

Part Four: Japan Has Become a Bond for the Multinational Force

Frequency of refueling from Japan to foreign countries: To the US, 296 times; to the UK, 23 times; to France, 55 times; to Germany, 12 times; to Spain, 10 times; to Greece, 10 times; to the Netherlands, 7 times; to New Zealand, 15 times; and to Pakistan, 57 times. The total was 552 refuelings as of October 8, 2005.

It was a very hot day, over 40 degrees. When the supply fleet started refueling, forty crew members were busy on deck. They were sweating all over, and the work generally takes from one to five hours.

In March 2003, the Iraq War was about to begin. Supply ship Tokiwa from Yokosuka base repeated this tough work and refueled seven other ships a day. They worked from 7 am to 8 pm for a month without holiday. The chief of the crew said, “It was tough work. I was worried about the condition of the crew.” One hour’s refueling enables a frigate to sail for four days. A mostly-American fleet started concentrating in the Arabian Sea for the coming Iraq War.

Supply ship Tokiwa refueling the USS Seattle during

Operation Enduring Freedom

The MSDF played an important role in supplying fuel to the multinational forces that confronted the terrorists’ organization in the Indian Ocean. Because ships en route to the Persian Gulf always pass there, fuel was supplied to all that were designated as working against the actions of terrorists. The amount of refueling that month shot up to twenty thousand kiloliters, which is twice the level of the previous month. A Japanese crew leader, Sawamura Koki (49), who was dispatched to the Indian Ocean three times, said, “It was the busiest period.” They received telegrams from the US, which informed them of the detailed actions of fifty ships from other countries such as France and Germany.

In summer 2003, Moriyama Susumu (35), a commander of the ship Haruna, that was dispatched from Maizuru, Kyoto, looked at the dispositions on the map with deep emotion. He said, “I felt that I was a member of the multinational force.” Japan has refueled fleets from eleven countries. It has refueled Pakistan since last July in addition to Western countries. Crews communicate with each other on the sea. A commander of the 61st ship of the tenth unit, Fukuda Takuo (55), got a message that said “We want to eat sushi,” before they supplied fuel to a Germany ship. So he told the cook to make “makizushi” for them. He said, “Because the work is monotonous, everyone looks forward to receiving supplies.”

The Japanese also performed taiko and kendo. In response, bottles of wine were sent from France, cookies from America, a box of apples from Pakistan, and so on. These were sent by the rope that tied the ships together. When an MSDF ship paid a goodwill visit on a long voyage around European waters this July, it received 630 free kiloliters of fuel in French ports in return for the Japanese refueling in the Indian Ocean.

A US admiral, who commanded the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk, expressed thanks to Japan in March 2003 at a press conference in Yokosuka, because the MSDF had refueled it indirectly through the U.S. supply fleet in the Arabian Sea in February 2003. The Anti-terrorism Special Measures Law provides that the activities in the Indian Ocean are to contribute to international society by eliminating international terrorism. The Iraq War was outside of this law. A highly-placed government official explained, “The aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk was also engaged in the operation against terrorists.” But the truth is not yet clear.

The amount of refueling to the multinational forces in the past four years was about 410 thousand kiloliters, ninety percent of it to US ships. The activities in the Indian Ocean mainly involved support to the U.S., but refueling for Pakistan also became frequent.

Koda Yoji (55), who has seen the whole process, said, “For 4 years Japan has kept on refueling without rest. Not only the US, but also other countries highly appreciate Japanese activities. Giving free fuel became a bond among multinational forces. It is something that only Japan can do.”

Part Five: The World’s Gaze Makes Japan Tense

The Changing Quantity of Refueling

Japan still refuels about ten ships a month, but the quantity of refueling has decreased sharply. The maximum was forty thousand kiloliters in March 2002, and the minimum was one thousand in August 2005. Nowadays the use of compact ships has increased, while large supply ships were common at first.

“How long will it take to complete the mission?”

“We can’t finish soon. I think it will take about ten years.”

When Shibata Masahiro (51), commander of the second unit, who was dispatched to the Indian Ocean in 2003, met commanders from Canada and Germany at sea, he talked about their activities with them. Because of the difficulty in tying down terrorist movements on the sea lanes, Shibata agreed with their view that the mission would be a long-term one.

Twelve countries, including Japan, joined the operations against terrorists at sea. The Japan Defense Agency said that it has inspected 11,000 suspicious ships, seized drugs, and arrested many crews since September 2001. However, it is not clear how this work actually contains terrorists. The MSDF has provided 410 thousand kiloliters of fuel, which is about the same amount that 400 Japanese ships consume in a year.

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi at a Naval Review

However, the quantity of refueling declined rapidly after the peak in 2002. Even some inside the MSDF say that Japan should shift to other activities now. Most of the commanders, however, feel that continuing to participate is important.

Because the Japanese fleet includes battleships that not only have artillery, but also missiles and torpedoes, their very presence shows foreign countries the “national will.”

Commander of the sixth unit, Kawano Katsuyoshi (50) thinks, “The presence of Japanese ships in the Indian Ocean means not only the Self-Defense Forces, but also Japan has taken a big step forward in international society.”

In 1991, the MSDF left Japanese seas for the first time to engage in disposing of sea mines off Kuwait. Commander Kawano says, “The difference from the activities in 1991 is that now Japan works in cooperation with ten other countries.” He also said, “Japan doesn’t go there to fire missiles. Working together with other countries in the same place is what is important.”

Admiral Kojo Koichi (59), who has been engaged in the mission from the beginning, told each commander, “This mission doesn’t mean just the support for US-UK military action. What you have done is for Japan. I want you to keep telling the crew this.” His words show his recognition of the fact that the sea lane that the fleet uses between Japan and the Indian Ocean is the same one that oil tankers use to link Japan with the Middle East.

The activities of the MSDF are limited to waters around Japan, except for military training in the US or for long-distance voyages. Long-term navigation stretching over half a year is an unfamiliar experience for Japan. Commander Tanaka Tsuneo (53) told a press conference, “I was inspired with confidence because I worked on such an intense mission” after finishing a 162 day voyage this September. Kawano said, “Japanese ability is highly estimated by other countries’ navies. The navy must go wherever it is ordered. The Japanese navy is likely to improve its weak points.”

The New National Defense Program Outline that was laid down at the end of last year states that the mission of the SDF is to join international operations to improve the international security environment as well as Japanese security.

On October 26th, the Japanese government decided to extend the term of the dispatch one more year based on the Anti-terrorism Special Measures Law. How will the MSDF change in the future? The mission to the Indian Ocean will be a key.

This five-part series, coordinated by Tanida Kuniichi, appeared in the Asahi Shinbun between October 29 and November 5, 2005. This slightly abbreviated English translation is by Eriko Osaki and Michael Penn of the Shingetsu Institute for the Study of Japanese-Islamic Relations http://www.shingetsuinstitute.com. Richard Tanter provided helpful suggestions for the improvement of an earlier version of the English translation.