To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred Year Journey Through China and Korea, 1910-2010

Tessa Morris-Suzuki

Everything was a strange contrast from what we had left; the cold colouring of Manchuria was replaced by a warm red soil, through which the first tokens of spring were beginning to appear. Instead of the blue clothing to which we had been accustomed, every one here was clad in white, both in town and country. Rice fields greet the eye at every turn, for this is the main cereal grown. The only things that were the same were the Japanese line and the Japanese official, no more conspicuous here than in Manchuria, and apparently firmly rooted in both.1

So wrote the British traveler Emily Georgiana Kemp (1860-1939), describing her crossing for the border from Manchuria into Korea a few months before that country’s annexation by Japan in 1910. Kemp had traveled through China several times before, but this was her first sight of Korea, and it gave her a vivid sense of entering a new world.

Kemp is an oddly forgotten traveler. While precursors and contemporaries like Isabella Bird (1831-1904) and Gertrude Bell (1868-1926) have been the subjects of much research and writing, Kemp remains a virtual unknown. Yet she was a remarkable woman: a scholar who was one the first women to study at Oxford University; an artist who exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago; and a dauntless traveler who not only journeyed through Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan but also crossed the Karakorums on horseback and was awarded a medal for her adventures by the French Geographical Society. Deeply religious, she was at the same time a proud feminist and outspoken advocate of women’s rights. Most extraordinary of all, perhaps, was her impassioned love of China, which survived and grew despite the terrible fate that overtook her family on Chinese soil: a fate that I learnt about only gradually, since Kemp herself maintained a deep silence on the subject.

|

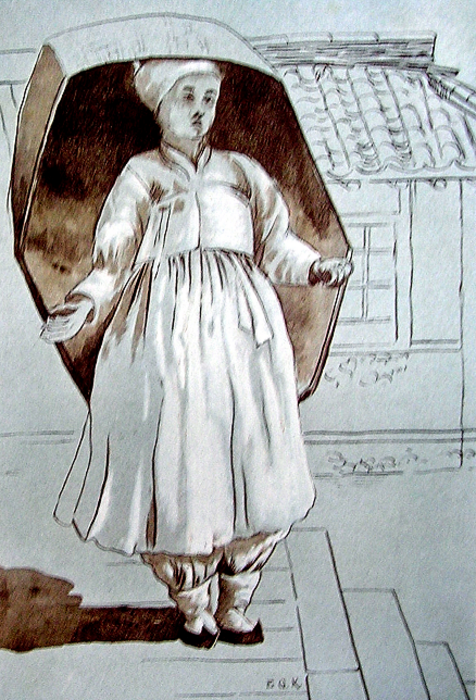

Self-Portrait of Emily Kemp in the Garb of a Chinese Travelling Scholar |

Her 1910 journey through Korea was beset by problems from the very start: friends in China had cheerfully assured her that Chinese was understood everywhere in Korea, so she and her traveling companion Mary MacDougall had hired a Chinese guide, Mr. Chiao, to accompany them on their travels. It was true that in the early twentieth century all Korean literati could read Chinese characters, but the travelers quickly discovered that most of the people they met on their journey were not literati, and the hapless Mr. Chiao spent much of his time hunting for local scholars or officials with whom he could communicate through messages written on scraps of paper or scratched into the dirt of unpaved roads. His task was not helped by the fact that their itinerary through Korea had been planned on a German map which rendered some place names into Germanized approximations that were utterly impossible to correlate with Korean, Japanese or Chinese equivalents

In spite of these handicaps, with the help of missionaries, English-speaking Koreans and Japanese, sign language and Mr. Chiao’s Chinese characters, Kemp and MacDougall managed somehow to find their way through the country, record a wealth of information and impressions, and sometimes even engage in conversations with local people. The exchanges of ideas that she achieved across the language barrier left Emily Kemp with a generally warm and positive image of Korea: “the people”, she wrote, “are naturally peaceful and diligent, and under a wise rule the land ought to become an ideal one.”2

Korea, “somewhat larger than Great Britain”, had a population that in 1910 was estimated at around twelve to thirteen million, though the figures were inexact, as the first attempt at a census had been taken by Japanese officials, and (Kemp noted) many people had avoided being counted for fear that the records would be used to impose new taxes.3 Like many of Emily Kemp’s observations of Korea, her comments on the first census are a reminder of how firmly the country was already under Japanese control by the first years of the twentieth century. The formal annexation of Korea in August 1910 was the culmination of a long process of colonial penetration, rather than its beginning.

|

Korean Landscape with Graveyard, by Emily Kemp |

Kemp’s fascination with the region arose from her awareness that it held the key to the destiny of East Asia. In the introduction to her travel account, The Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, which she completed just four days after Japan’s annexation of Korea had been formally announced, she reflected on the shifting power balance in the region from the collapsing China Empire to the newly ascendant Japan:

The European and other Powers who have wrangled over the possibility of commercial and political advantages to be obtained from the Chinese Government (after the Boxer troubles) have withdrawn to a certain extent, but like snarling dogs dragged from their prey, they still keep their covetous eyes upon it, and both Russia and Japan continue steadily but silently to strengthen their hold on its borders. These borders are Manchuria and Korea, and it is in this direction that fresh developments must be expected.4

For it was here that the decisive step in Japan’s imperial advance was being taken: “the latest step in advance is the annexation of Korea, the highroad into Manchuria”.5

A century on, the region where Kemp traveled is once again in the grip of momentous transformations. The rise of China is overturning the old certainties of regional and global power relations. As the world confronts economic crises, China, the last major self-proclaimed Communist power, has ironically come to hold the key to the future of global capitalism. Just as Japan’s ascendance aroused international anxieties in the first part of the twentieth century, in the early years of the twenty-first century China’s assertiveness evokes a similar mixture of admiration and nervousness from regional neighbours, and from the wider world. Above all, though, a century after the annexation, it is the fate of the Korean Peninsula that lies in the balance: Korea still divided by the world’s last Cold War frontier, still formally at war in a military conflict that has lasted sixty years.

It was against that background that, in search of fresh understanding of the region’s past and future, almost a century after Kemp’s journey I set off to retrace her footsteps through northeastern China and Korea in the company of my artist sister Sandy and doctoral researcher Emma Campbell. Kemp’s writings proved to be a fascinating guidebook. Some of her stopping points: such as the Manchu tombs of Mukden (today known as Shenyang) and Seoul’s royal Gyeongbok Palace are familiar landmarks on the twenty-first century tourist itinerary. But others, like China’s Thousand Peaks (Qianshan) and the beautiful, rugged eastern coast of North Korea are little known to the outside world today.

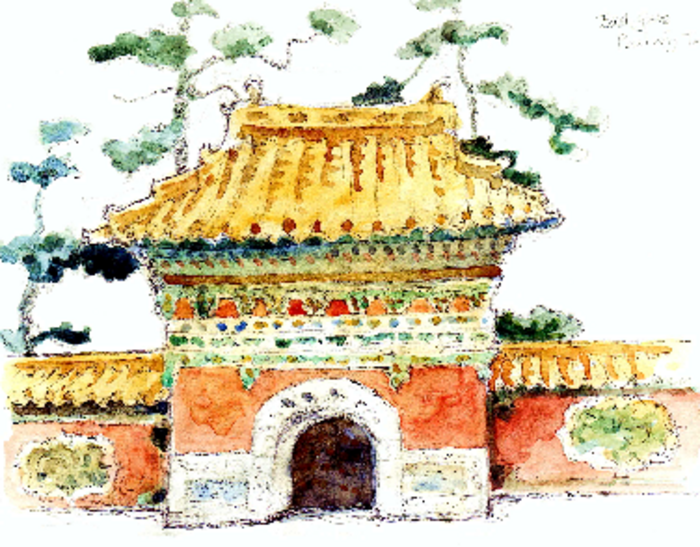

Left: Gateway to Manchu Tombs, Shenyang, by Emily Kemp (1910)

Right: Gateway to Manchu Tombs, Shenyang, today, by Sandy Morris

Of course, the surviving remnants of Cold War politics make a precise replication of Kemp’s route impossible. There is no way to travel directly from North to South of the Korean Peninsula, and our journey had to take a more complex and serpentine course. With Kemp’s writings as our guide, we found ourselves along the way soaking in the hot spring baths of a crumbling Manchurian hotel once frequented by China’s Last Emperor Pu Yi and his opium addicted wife Wan Rong; being taken on a guided tour by young men who smuggle goods across the China-North Korea border; and chatting to a friendly fisherman on a glorious and deserted stretch of beach near the North Korean city of Wonsan, as we attempted to follow Kemp’s course to the intended highlight of her Korean itinerary: the Diamond Mountains (Mount Kumgang), which lie just north of the 38th Parallel that now divides the Peninsula.

|

Kemp and MacDougall’s Itinerary through Manchuria and Korea (Solid lines show the route of their journey through Korea and Manchuria; dotted lines show a side trip to China, not described in Kemp’s book, and a detour through Dalian taken on their journey back to Russia) |

The Water-Carriers of Pyongyang

Korea today is a peninsula divided, not just by barbed wire, mines and all the monstrous machinery of modern warfare, but also by words. The old differences in regional dialect between north and south have been sharpened by ideology; foreign words imported since division in 1945 – “helicopter”, “cable car” – have been translated differently on either side of the 38th parallel. Our North Korean driver Mr. Kim gives a broad smile, revealing the gleaming gold fillings in his teeth, when I use the phrase ireopseumnida, which in North Korea is polite and means “it’s not a problem”, but in South Korea means “mind your own business”. The rival governments on either side of the divide have developed different systems for converting Korean characters into the Roman alphabet, causing endless problems for people (myself included) who write books in English containing place names in both North and South.

Most troublesome of all is the divide in the name given to the country itself. When Cold War Germany was divided in two, both halves at least still called themselves Deutschland. But in Korea, the regimes on either side of the Cold War dividing line chose to inherit different versions of the historical name for Korea. The North became the Democratic People’s Republic of Choson (Joseon in South Korean romanization) Minjujuui Inmin Konghwaguk, using the official name used by the Korean kingdom known for most of its history since the fourteenth century. (Choson is often translated into English as “Land of Morning Calm”, though Emily Kemp, more correctly, translates it “Land of Morning Freshness”.) The South became Daehanminguk (“Great Nation of the Han People”), “Han” being another archaic term for Korea, briefly revived by the modernizing Korean Empire between 1897 and 1910. The search for a shared name is just one of the multitude of roadblocks that litter the path towards reunification.

The problem of names also has other, more subtle effects. Not only Koreans themselves but also their neighbours, the Japanese and Chinese, have come since 1945 to use their own versions of the two different names for the two halves of the peninsula and its people. The people of the North are known in Japanese as Chōsenjin and in Chinese as Chaoxianren; the people of the South are Kankokujin in Japanese and Hanguoren in Chinese. When Japanese people remember their country’s annexation of Korea, they use the term Kankoku Heigō, which roughly (and ambiguously) means “unification with” or “absorption of” Korea – but the term for “Korea” in this phrase is the word which today means “South Korea”.

The of Kankoku Heigō has prompted much debate in the Japanese media about appropriate ways for Japan and its neighbour Kankoku – South Korea – to collaborate in commemorating the 100th anniversary of this event in 2010. But the debate also serves to deepen a strange shadow in Japanese memory – a shadow that obscures recollections of colonial expansion in the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Few if any Japanese people, as they watch the military parades in Kim Il-Sung Square which regularly accompany news items on the North Korean “rogue state”, think of Kim Il-Sung Square as the place that once housed the offices of the Japanese-run telephone exchange and Chōsen Bank in the city of Heijō (the Japanese colonial-era name for Pyongyang). Few of the Japanese media consider how Japan and its other neighbour, North Korea, might come together to commemorate the memory of the annexation. As time goes on, Japan’s colonial rule in Korea is increasingly remembered as a colonization of South Korea, while the colonial history of the North is consigned to uneasy oblivion.

The Water Carriers of Pyongyang

As Emily Kemp and Mary MacDougall arrived in Pyongyang in the early afternoon, and climbed into the sedan chairs prepared by a Korean Christian missionary who was waiting to meet them, they saw the “handsome large new red brick barracks” and the “Japanese suburb” that were rapidly growing up around Pyongyang Station. With interpreter Mr. Chiao and the Korean missionary walking behind while conducting a silent conversation in written Chinese characters, the two women were carried in their chairs through streets lined with stalls selling a multitudinous array of unfamiliar foods: “dried cuttle fish hang up in rows, and are a tasty dish in the eyes of the natives, and all kinds of other fish are dried and hung up in strings to form artistic designs for the adornment of the shops, as well as for the benefit of the purchasers.”6 Kemp was delighted by the exotic clutter of these alleyways, but (as she had in Harbin) lamented the steady spread of architectural modernity across the face of the city: “it is sad,” she wrote of Pyongyang, “to see every place being disfigured by European-looking erections of the ugliest and most aggressive type”.7

Emily Kemp’s ambivalence towards the western presence in Northeast Asia is mirrored in her ambivalence towards the Japanese presence on the Asian continent. As the child of a socially-conscious industrial revolution pioneer, she wholeheartedly welcomed the modern medicine, hygiene and education which foreign intruders brought to Manchuria and Korea. But, as a traveler who delighted in the exotic landscapes, sounds and physical sensations of Asia, she lamented the vanishing traditions displaced by modernity.

A sight that instantly attracted her attention in the streets of Pyongyang was the presence of water-carriers, since all the city’s water was still drawn from the river. Unlike other parts of Korea, where the heavy work of water-carrying was often done by women, the water-carriers of Pyongyang were mostly men, who bore their precious burden in pails on their backs. By 1910, however, the Japanese authorities, already in de facto control of the city, had just completed new waterworks on the banks of the broad Taedong River which flows through the centre of Pyongyang, and on Rungna Islet in the middle of the river itself. The waterworks were a highlight of the Pyongyang tourist itinerary, and as she visited them Kemp observed wistfully that “soon that picturesque being – the water carrier – will be nothing more than a memory; but undoubtedly the advantages of a good water supply will reconcile the inhabitants to the change.”8

|

The Waterworks of Pyongyang under Construction, c. 1910 |

The waterworks were just part of a profound colonial reshaping of the city, whose influence can still be seen throughout the centre of Pyongyang today. Visiting Pyongyang almost two decades before Kemp, the missionary James Gale had found an ancient city still enclosed in high walls. In the remote beginnings of recorded history, the area around Pyongyang was a place of intense interaction between Korean and Chinese kingdoms, and high on Moranbong, the forested hill overlooking the Taedong River, stood a weathered monument which for almost a millennium was revered as the tomb of the semi-mythical Chinese figure Kija. Known as Jizu in Chinese, Kija was said to have fled from Shang China to Korea more than a thousand years before the start of the Common Era, and to have ruled the northern part of the country from Pyongyang.9 When Gale passed through the city in the early 1890s, aristocrats who claimed descent from Kija still lived in the hills to the south, while in the hills to the north was a “citadel” of Buddhist temples, whose “beauty and strength of situation gives one an idea of the power Buddha once possessed” in Korea.10

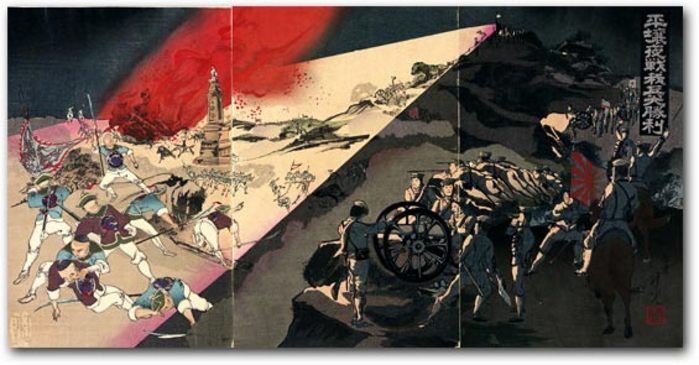

But in 1894 disaster struck Pyongyang. The city had the misfortune to lie in the path of Japanese troops as they marched northward towards the Yalu River, and of the Chinese army as it sought to confront them, and so became the site of one of the fiercest conflicts of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. After the battle, the city of Pyongyang (wrote Gale),

was strewn with corpses, and the once busy streets were silent, for the inhabitants had scattered, no one knew whither. A Korean with his wife and three children, escaped through the thick of the fight, and by climbing the wall reached safety. He had been a man of some means, but of course had lost everything. He said he was thankful he had his three children spared to him. The little black-eyed girl had heard and seen that night what she would never forget – the rattle of Murata rifles and the other hideous accompaniments of war.11

|

Contemporary Print of the Battle of Pyongyang by Kobayashi Toshimitsu |

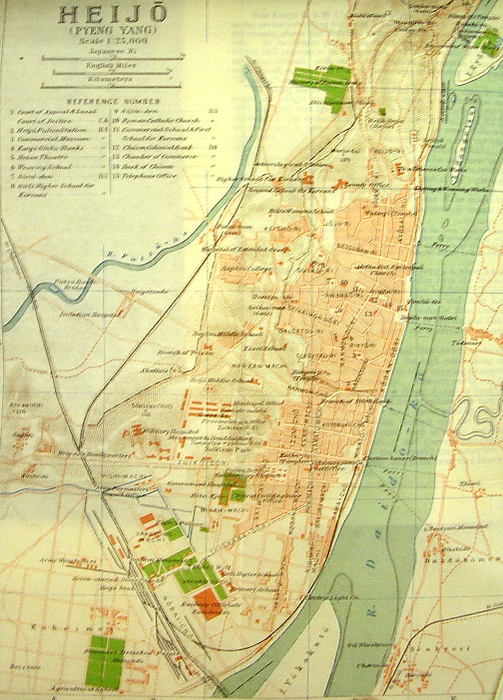

Japan’s growing domination over Korea following its victory in the war provided an opportunity to impose a new geometry of modernity on the shattered city. The “Japanese suburb” that Emily Kemp saw springing up around the station was part of an urban design that prefigured the grand Japanese experiment of Manchukuo’s “New Capital”. A broad, straight avenue – Teishaba Dōri [Japanese for “Station Avenue”] – was laid out from the railway station towards the Taedong River, where a new town of shops, offices and warehouses, planned on a grid pattern like that of American cities, accommodated around 6,000 Japanese settlers, alongside the old city’s Korean population of some 36,000.12

|

Colonial Era Map of Heijō (Pyongyang) |

In this new Pyongyang, however, parts of the old were carefully preserved. From the colonizer’s perspective, Kija’s role in Korean history was evidence of the country’s historical subordination to China, and therefore of its lack of cultural creativity and political autonomy. Kija’s tomb became a key exhibit in a new Japanese colonial version of history that smothered Korea’s claims to independence, and was a landmark visited by most foreign travelers to Pyongyang in the first half of the twentieth century. Emily Kemp climbed the forested slope of Moranbong and found the tomb surrounded by a dense grove of pine trees. It was “tightly shut and barred”, but she and Mary MacDougall were able to catch glimpses of the grave mound with its surrounding retinue of stone animal and human guardians. Like most visitors, they were captivated by the breathtaking view from Moranbong over the sparkling river and the fields and hills beyond. But, as Kemp noted sadly, the walls of Pyongyang, dating according to legend from the days of Kija himself, were “now in the course of demolition”. This, she added wryly, “synchronises with the coming of the first party of [Thomas] Cook’s personally conducted tours!”13

Three years later, Korea’s new colonial rulers would begin the construction of a grand wooden hall with steeply sloped thatched roof on the hill near Kija’s tomb. This was to be Pyongyang’s Shinto Shrine, where not only the city’s growing Japanese population but more particularly the indigenous Korean inhabitants would be required to pay homage to the descendant of Japan’s primordial Sun Goddess, Amaterasu Ōmikami: the Japanese Emperor in distant Tokyo. Needless to say, no trace of the Shinto Shrine remains in today’s Pyongyang.

The further she traveled in Korea, the more Kemp became aware of a dark side to colonial modernity – a cultural violence that went beyond the irresistible retreat of the past in the face of encroaching modernity. Even in these final months before the formal annexation of Korea, the Japanese government continued to disavow any plans for full-scale colonization, insisting that their presence was merely a protectorate exercised with the consent of the Korean king. But, Kemp observed,

instead of trying to make their protectorate as conciliatory as possible, they too often do the reverse;… In many ways they are doing a great deal which should benefit the country, but in such a manner as to make it thoroughly obnoxious. It is little use to repudiate the idea of annexation, when they trample on the dearest wishes of the Korean, and treat him as a vanquished foe.14

The Sound of Silence

The Pyongyang landscape which entranced Emily Kemp when she visited Moranbong can be seen in even greater splendour from the landmark to which every foreign visitor is taken today: the Tower of the Juche Idea. Kija, with his foreign and colonial associations, has fallen out of fashion and his tomb has been destroyed; for Juche Thought is above all else profoundly nationalistic. From the summit of the soaring white tower, surmounted by its stained glass flame, you can look out to every side across the city, and over the glittering midnight green waters of the Taedong river flowing serenely through its heart.

|

Pyongyang from the Tower of the Juche Idea |

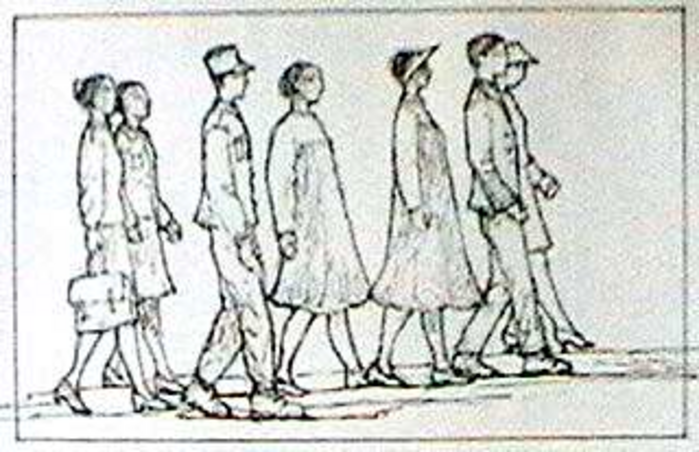

The broad avenues and squares of the city are kept immaculately clean by legions of track-suited residents, performing their required civic duties with trowels, dustpans and brooms. The occasional truck or bus clatters past, but most of the traffic is pedestrian. The people of Pyongyang – men in black suits or army uniforms, women in demure skirts and blouses, children in school uniforms or sports gear – move with the distinctive gait of those used to walking long distances: unhurried, heads held high, arms swinging rhythmically by their sides. In the parks along the banks of the Taedong, with their neatly trimmed grass and disciplined topiary, the citizens fish, smoke, or squat in the shade of trees, reading books. The azaleas are in flower, and willow branches, delicate with the green of spring, touch the water’s surface.

There is a strange resonance to the open spaces of Pyongyang, a deep silence lying beneath the blasts of martial music and mournful electronic midday and midnight chimes that issue from above the rooftops. Before a truck or bus appears, you can hear its approaching sound from far away, and the deepening grind of its engine continues to reverberate long after it has disappeared from view: for Pyongyang, with its population of over three million, lacks the sound that permeates every other city today – the ceaseless background hum of vehicles.

|

Pedestrians, Pyongyang (Sandy Morris) |

When, in my early teens, I first lived in a big city, I would wake at night and listen in terror to that sound – the deep inhuman endless roar of the metropolis. Now the sound of the city has become so familiar that (like most people) I no longer hear it; but in Pyongyang, I hear its resounding absence.

At breakfast in the huge dining room of our hotel, with its white linen tablecloths and crystal chandeliers, there is no menu, but only a rather shy waitress who seems very eager to please. After some consultation and a long wait, she produces large quantities of bread and fried eggs, and quite drinkable hot coffee. At the table next to ours an extended family, ranging from frail grandmother to small children, is conducting a conversation in a mixture of Korean and Japanese. Our guides, Ms. Ri and Mr. Ryu, tell us that this hotel is often used by Korean families from Japan and even the United States who have come to North Korea to meet long-lost relatives. Later we see the same family on the steps of the hotel. The grandmother stands shakily, bent double over a walking stick. There are tears pouring down her face.

Mr. Ryu is up early, revising his text for the day as he waits to meet us in the lobby. Although he is a older than his female colleague, he is (we discover) a newcomer to this job, having completed his military service and also worked as a researcher for some years before becoming a guide. His English is less polished than Ms. Ri’s, but his determination makes up for his lack of experience. Every spare moment is spent memorizing information and revising texts, so that, even though he sometimes stumbles over other words, English phrases like “under the wise leadership of the Great Leader Kim Il-Sung” flow smoothly and fluently from his tongue.

“I liked the army,” he says. “It was really hard work, but it was enjoyable too. You feel as though you’re an important person when you’re in the army.”

He does not really seem the military type, though. He looks more like a schoolteacher, which he was briefly before becoming a soldier. His black suit hangs loosely from his tall and gangly form, and the real loves of his life, I suspect, are his wife and the baby daughter whose photo he carries around with him in his wallet. In the car, as we drive beside the Taedong River, he rather bashfully shows us the little image of a tiny round face surmounted by tufty hair, and for a moment his eyes lose their sadness and are illuminated with a smile of pure fatherly joy.

Today’s Pyongyang is the product of a second wave of destruction and reconstruction, even greater than the first. Just as most Japanese people have forgotten the devastation of Pyongyang during the Sino-Japanese War, so most Americans, British, Australians and others have forgotten (or have perhaps never been aware of) the obliteration of Pyongyang during the Korean War.

The North Korean government does little to remind them. The memory of war is tangible everywhere in the city, but the stories that are commemorated are those of heroic resistance and brilliant victory. In the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in central Pyongyang, a cheerful young woman soldier proudly displays the massive dioramas depicting the great battle of Daejeon (in South Korea) where “our forces totally destroyed one big American military division at that time” and the titanic struggle at the Chol Pass where “the fighting spirit of the drivers of the People’s Army, under the guidance of our Great Leader, utterly frustrated the enemy’s plot to crush the Korean people.” With that passion for statistical trivia displayed by guides all over Korea, she also breathlessly informs us that the depiction of Daejeon, which covers the entire wall of a circular hall with a rotating platform in the centre, is “fifteen metres high and one hundred and thirty-two metres around and forty-two metres in diameter and from this place to the painting is thirteen and a half metres and on this one picture our artists have painted more than one million people”.

She pauses for breath before confessing, “but for me, I have continuously counted, but I cannot yet completely count them all”.

|

Section of the diorama illustrating the Battle of Daejeon, Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, Pyongyang. |

The Victorious Fatherland Liberation War, she explains to us, began on 25 June 1950, when “the American aggressors attacked our country from the south, over the 38th Parallel, and our Great Leader ordered our soldiers to frustrate the enemy’s challenge by going over to the counter offensive. And on the occasion of this war our Great Leader ordered that in one month we must liberate the whole South Korea. But our soldiers had not many weapons and the American aggressors brought massive reinforcements from their own country and from the Mediterranean Fleet and from the Pacific Fleet, and with these reinforcements they temporarily occupied some areas of the North, including Pyongyang, so our Great Leader Kim Il-Sung ordered our soldiers to temporarily retreat to the north. But then American imperialists bombed some places in China over the Yalu River, so the Chinese sent us volunteers, and together with our People’s Army they began a new offensive and we drove the Americans south of the 38th Parallel.”

The Chol Pass diorama, brought to life with the aid of melodramatic sound and light depicting enemy planes swooping low over the pass and the crackle of anti-aircraft fire, is (she says) very popular with children.

But everyday stories of human suffering fit uneasily with this strident official narrative – in which North Korea the victim is instantly transformed into North Korea the victor. I look in vain for a commemoration of two days in the life of Pyongyang that I read about shortly before leaving Australia: days whose statistics seem more significant than the dimensions of the Daejeon panorama. 11 July 1952: the day when US, British, Australian and South Korean planes flew 1,254 bombing sorties and dropped 23,000 gallons of napalm on Pyongyang and its inhabitants. 29 August 1952: the day when the number of sorties reached 1,403, and around 6,000 citizens of the capital were killed.15 The bombardment of Pyongyang ended a few days later, when the US command decided that there was too little left in the city to justify the effort of attack.16 By then, 80% of the city’s buildings were in ruins.

|

Aftermath of Korean War bombing, Pyongyang |

As we leave the museum, our Mr. Ryu remarks in passing, and without any noticeable sign of bitterness, that both his grandfathers and one of his grandmothers were killed in the Korean War. Such stories are commonplace here.

The new city that rose from the chemical saturated rubble was revolutionary defiance expressed in concrete, stone and marble. Pyongyang was to be the living embodiment of Juche Thought. Its buildings would be grander, its entertainments more lavish, its culture more elevated than anything other capitals could offer. The Tower of the Juche Idea, at 170 metres, is 70 centimeters taller than the Washington Monument, which it closely resembles. The Arch of Triumph, built to commemorate Korea’s heroic resistance to Japanese colonialism, is the biggest triumphal arch in the world. As Mr. Ryu explains (displaying the fruits of his careful homework) it is sixty metres high and fifty meters wide, while the French version stands at less than fifty metres in height and is a paltry 45 metres in width.

But although North Korea’s leaders proclaimed their determination to erase all traces of the colonial city, the street grid which Japanese modernizers laid out in the early 20th century in fact provided a good foundation for the Juche capital, and its outlines can still be seen beneath the widened avenues and socialist neo-classicism of today’s city. Station Avenue, successively renamed “People’s Army Street” and then “Willow Street”, and now known as “Glory Street”17, still runs as straight as an arrow from the station towards the city centre. The main road that once bisected the Japanese business district of Yamato Machi (Japan Town) was straightened and broadened in the 1950s, and given a new name: Stalin Street. Today it is Victory Street – like the Arch of Triumph, a commemoration of the defeat of colonialism.

The island in the Taedong River which housed the Japanese-built waterworks is home to the May Day Stadium, where North Korea’s breathtaking Arirang mass-games are staged. But Moranbong remains, as it was when Emily Kemp visited, a popular picnic spot, while the museum built to commemorate the founding of North Korea’s ruling Workers’ Party occupies a colonial period edifice which looks suspiciously like the Diet Building in Tokyo and its alter-ego, the State Council building in Manchukuo’s lost capital of Xinjing (today’s Changchun). And at least until recently North Korea’s monument to the fallen soldiers of the People’s Army stood on the very spot where the Japanese colonial authorities had commemorated their soldiers killed in the 1894 Battle of Pyongyang and other imperial conflicts. The nationality and politics of “our glorious dead” change, but the rituals of remembrance remain much the same.

Sunday in Pyongyang

Pyongyang is a reward for virtue. To live in the capital is the ultimate mark of success, for (more than almost any other capital city) Pyongyang is dominated by the presence of the social and political elite. Guard posts on the roads into the city carefully protect it from any influx of undesirable rural poor. The apartment blocks that face onto the wide main streets present a bland superficial face of modernity. Emily Kemp would be horrified. Yet looking down from the summit of the Tower of the Juche Idea, you can see how each of the older apartment complexes forms a square surrounding and containing lines of rickety grey roofed one-story cottages: hidden villages stowed away in the heart of the metropolis.

|

Apartment blocks, Pyongyang |

No building more powerfully proclaims the utopian vision of Pyongyang than the Grand People’s Study House.

In the early twentieth century, the gentle hill in the city centre where the Study House now stands was occupied by Pyongyang’s Catholic church and Methodist Episcopalian mission: the latter described by Emily Kemp as a compound of buildings in “American style”, including a fine large church with a belfry “which can be seen as well as heard from afar.”18 Both churches were flattened during the Korean War19, and their space is now occupied by a palatial neo-traditional structure of white marble columns and tier upon tier of jade green tiled roofs. The Grand People’s Study House, completed in 1982, is not only North Korea’s national library, but also a research centre, adult education college and general disseminator of enlightenment.

To one side, in a paved expanse worthy of the Palace of Versailles, torrents of surprisingly clear water flow though a series of fountains, waterfalls and ponds, between the crags of miniature mountains, around gnarled pine trees and over rocky causeways. A group of boys in pioneer uniforms – red scarves round their necks, the cuffs of their white shirts and blue trousers rolled up – balance perilously, with shrieks of delighted fear, on the boulders in the middle of the torrent. Mothers have brought their toddlers for a picnic in the square, and one wipes her little daughter’s sticky fingers with a flannel dipped in the waters of the fountain.

Nearby, a newly-wed couple – the bridegroom in a grey suit, the bride in a high-waisted, wide-skirted pink chima jeogori adorned with golden flowers – laughingly play the rock-paper-scissors game as their wedding photographer darts around them selecting the best angle for his shots. There seem to be few guests in attendance, but several passers-by stop to offer smiles and waves of blessing at the couple.

North Korean marriages are still often arranged in traditional fashion by a go-between, who helps to check the political and social pedigree of the partners. Our guide Mr. Ryu’s wedding, he tells us, was arranged by his superior in the army. But here as elsewhere in Asia, arranged marriages do not preclude love, and Mr. Ryu promises us that, when his fellow guide and driver are not around to hear, he will tell us the story of how he fell in love with his wife.

“Chima jeogori are so beautiful,” remarks Sandy to Ms. Ri as we watch the bride pose in front of the fountains.

“Yes,” replies the guide, adding, with a surprising and conspiratorial smile, “also, very useful if you happen to have any little accidents between your engagement and your wedding.”

|

Wedding, Pyongyang |

The imposing Methodist Episcopalian church, which Emily Kemp visited and whose bells rang out over central Pyongyang, was at that time just part of a rapidly growing network of Christian churches throughout the city. In 1910 Pyongyang’s population of 40,000 was said to include about 8,000 Christians, and Kemp and MacDougall were able to spend the Sunday of their stay in the city happily touring one church after another (though in the case of the Methodist church, they slipped out quietly as the sermon began).20

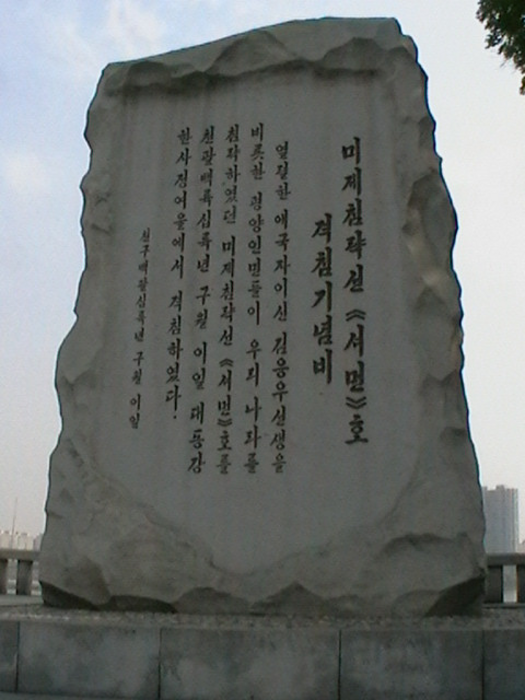

The first western missionaries to arrive in Pyongyang had not received a warm welcome. A Scottish pastor, Robert Thomas, armed with a trunk full of bibles, attempted to enter the city in 1866 aboard the General Sherman, an American vessel chartered by a British trading company as part of an audacious attempt to persuade the “hermit kingdom” to open its doors to trade. The voyage was a disaster that ended when the ship ran aground, the panicked crew fired cannons into a Korean crowd which had gathered nearby, and the incensed crowd set fire to the vessel, killing all on board. Korean defiance against “aggression by the American imperialist invasion ship General Sherman” still looms very large in North Korean historical imagination, and is commemorated by a large stone monument on the banks of the Taedong River, symbolically placed next to the USS Pueblo, the American spy ship captured by North Korea in 1968.

|

Monument to the Destruction of the “General Sherman”, Pyongyang |

But after initial hostility, in the first decade of the twentieth century the churches in the northern cities of Wonsan and Pyongyang experienced a sudden conversion boom – perhaps a response to the turmoil of war and encroaching colonialism. The Presbyterian Central Church, a lovely simple building in traditional Korean style, was large enough to contain a thousand worshippers, but when Kemp and MacDougall worshipped there it was often full to overflowing, and thirty-nine new churches had been set up in surrounding areas to accommodate the growing number of converts. By 1910, Pyongyang was already gaining its reputation in missionary circles as “the Jerusalem of the East”.

At the Central Church, Kemp and MacDougall met its Korean pastor, the fiery Reverend Kil, a convert to Christianity whose enthusiasm and energy seems oddly to resonate with today’s 150-day campaign:

When his people seemed to be growing careless, he started a daily prayer meeting at 4 o’clock in the morning, and this was soon attended by six or seven hundred people, with the result that a great revival took place, and his people promised to spend over 3000 days in trying to win others to a knowledge of Christ.

|

Open Air Evangelization in Colonial Pyongyang |

Kemp and MacDougall arrived at the Central Church just as a women’s bible class was starting, and Kemp was enthralled by the sight of the congregation – some wearing the giant hats with which Pyongyang women shielded themselves from male gaze – and by the children, who looked to her like “a gay group of butterflies”:

Nowhere (observed Kemp) could there be found a more attractive sight than the hundreds of white clad women, carrying their books wrapped in cloth tied round their waists in front, or their children tied on behind, the little ones dressed in every colour of the rainbow.21

These images invite speculation. Was a devout young Korean Christian woman named Kang Pan-Sok, daughter of Presbyterian church elder Kang Tong-Uk, amongst the white-clad women who attended this gathering of women at Pyongyang’s Central Church?22 In 1910, Kang Pan-Sok would have been eighteen years old. Two years later, she would give birth to her first son, Kim Song-Ju, who (after changing his name to Kim Il-Sung in adulthood) would then go on to become the Eternal President of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

After being taken on the obligatory pilgrimage to Kim’s giant gleaming statue near the site of the vanished Methodist and Catholic churches, it is tempting to superimpose on that image of the gargantuan bronze figure the alternative image of a white-clad young woman in her early twenties, with a butterfly-like infant strapped to her back as she said her prayers.

|

Young Korean Woman, Pyongyang, 1910, by Emily Kemp |

Chilgol, the village on the outskirts of Pyongyang where Kim Il-Sung’s mother grew up, was later transformed by her son (by then North Korea’s Great Leader) into “Chilgol Revolutionary Site”, an open-air museum dedicated to her memory. But, rather unusually for a revolutionary site in a nation dedicated to the Juche Idea, Chilgol contains a church, built in 1992 and said to be a replica of the church attended by Kang Pan-Sok.23 Presumably, the original must have been one of the dozens of little Presbyterian churches built by the faithful from Pyongyang’s Central Church to accommodate their overflowing flock.

The Chilgol church is just one of two Protestant churches in Pyongyang. The Pongsu Church, a little nearer to the city centre, is built in a similar unpretentious style, and is attached to noodle factory, where flour sent by Christian aid groups overseas is turned into meals for primary school children and the elderly. Its services are, on special occasions at least, accompanied by hymns sung by a choir of students from Kim Il-Sung University. Pyongyang also boasts Catholic and Russian Orthodox churches, and a mosque in the grounds of the Iranian embassy.

This strange presence of religious structures at the heart of an avowedly atheist country evokes all kinds of questions to which I expect no answers. Clearly, ordinary North Koreans are not free to choose their own religion. Unauthorized possession of a bible, indeed, is likely to bring down the most terrible punishments on the head of the offender. Who, then, are the Koreans who attend the Chilgol, Pongsu and Catholic churches? Why was Kim Il-Sung willing and even eager to reconstruct his mother’s church in the heart of the Revolutionary Village? What do the students of Kim Il-Sung University think about as they sing their Christian hymns?

The further I travel through North Korea, the more I am intrigued and perplexed by that strange and elusive phenomenon that we call “belief”.

The Cranes of Immortality

Beautiful scenery. Hwang Sok-Min stands lost in deep thought, gazing on the beautiful scenery…The inner stage is lit up, and fairies come down on it from the rainbow-spanned sky. The poor little Sun I appears and calls “Pa-Pa!”…

[Chorus]

Tell O Kumgang-san, Kumgang-san mountains

How many legends are there woven around you!

Here’s a girl crying for her father.

O Kumgang-san, is her story also a legend?

Legends flourish in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. In the revolutionary opera The Song of Kumgang-san Mountain, which premiered in 1973, choruses of fairies provide a backdrop to the story of a family torn apart by the cruelties of Japanese imperialism. The father, Hwang Sok-Min, who loves to play songs to his family on a bamboo flute, leaves his wife and baby daughter in the Diamond Mountains to join Marshall Kim Il-Sung’s heroic partisans fighting colonialism in Manchuria, and becomes a successful composer of revolutionary songs. After Liberation, the mountains – long denuded by the depredations of wicked Japanese landlords – are transformed into a socialist paradise bedecked with flowers.

The opera concludes with a moment to delight the hearts of all lovers of melodrama, when the poor little Sun I, now grown to beautiful maidenhood, is chosen to travel to the capital and sing in an opera set in her home village, but performed on the stage of Pyongyang’s Moranbong Theatre (which stands on the site of the long vanished Japanese Shinto Shrine). As the star-struck and nervous Sun I rehearses under the direction of the opera’s famous composer, the young singer clutches an old bamboo flute which the composer suddenly recognizes. This is the very flute that the composer himself played long ago as a young man before being parted from his beloved family, and yes, Sun I is indeed his long lost daughter.

The play-within-a-play concludes with the assembled cast heralding the glories of Kim Il-Sung, our Sun.

|

Illustration from the Libretto of the “Song of Kumgang-San Mountain” |

Kumusan Memorial Palace lies to the north of Pyongyang’s city centre, surrounded by a moat where swans glide through the reflections of the willow trees. Emily Kemp, on her travels, often encountered pheasants in the forested mountains of Korea, and at Kumusan for the first time we catch a glimpse of a brightly plumed cock pheasant strutting across the manicured lawns.

The opportunity to visit this place is a rather unexpected honour. Until recently, the palace was off limits to all foreigners except official guests of the state. Its waiting room, with brown marble walls, looks like the lobby of an office suite, which perhaps it once was; for this was the heart of North Korea’s political world: both Kim Il-Sung’s home, and the office complex from which he and the senior Party leadership managed the affairs of the nation. Today, this is the mausoleum where the Eternal President lies in state.

Before entering the main precinct, we must hand in all our belongings except for purses. Cameras and cigarettes are particularly sternly forbidden, and a body search is carried out to make sure that none are secreted on our persons. A green plastic shoe cleaner removes the detritus of the outer world from our feet, and we step onto a conveyor belt that glides silently along immensely long corridors, over the moat and into the realm beyond. I am reminded of the beautiful Bulgugsa Temple in South Korea’s Gyeongju, where a great moat once separated the transient world outside from the sacred space within.

Here in Pyongyang, the walls between which we move are lined with marble friezes of cranes – the symbol of eternal life. In North Korea, there is a legend that on 8 July 1994, the day when the Great Leader Kim Il-Sung died, a throng of cranes descended from the sky and gathered on the roofs and walls of his palace.

Beyond the corridors lies a hall watched over by female attendants clad in black velvet Chima jeogori embroidered with golden suns. A vast statue of the lost leader is set at one end of the hall, against a background of the rising sun.

As we enter the next chamber, a black-clad attendant hands us each an audio set with an English language explanation of the world beyond. As well as the Iranians, there are several other foreigners in the room, moving quietly through the hall amongst the large and orderly groups of North Korean visitors.

The taped narration is intoned in deep and dramatic cadences by a male voice with an unmistakable north-country English accent. The foreigners move through the room with downcast countenances and audio sets pressed tightly to their ears, assiduously avoiding one another’s eyes.

Now we have reached the heart of the mausoleum, but before we enter it, there is a further stage of cleansing. We pass through a gateway where blasts of air sweep away impurities from our clothes and bodies. In the middle of the sanctum beyond stands a glass case, with a long line of people waiting nearby. We join the line, and then go forward in groups of three to bow our heads before the glass case. I look at the faces of the others in the room. A few of the Korean women wipe away a tear, but the expressions on most faces are difficult to read.

The figure in the glass case wears a suit, and his head rests on a traditional Korean pillow. No longer monumental or giant sized, with faint marks of age on his face, he looks as though he is sleeping.

|

Moat of the Kumusan Memorial Palace, Pyongyang |

Later, when we eat dinner with a group of guides from another tour party, Sandy (who is better than me at asking forthright questions) says to one of them,

“In your country, what do you think happens to people when they die?”

“It depends,” says the North Korean pensively. “Some people like to be cremated. Some people like to be buried. Some want to come back in another life.” He gives a little laugh and then says, “No, only joking… But who knows. Sometimes when one person dies, another one like them is born…”

But all that, he insists, is quite different from the eternity of Kim Il-Sung.

“He is with us forever.”

Remembering the figure lying in endless state through days and long dark nights in the glass case at the heart of the Kumusan Palace, I suddenly feel filled with sadness for all the butterfly children whom Emily Kemp glimpsed, flying through fleeting shafts of sunshine into the winter gales ahead.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History at the Australian National University and an Asia-Pacific Journal Associate. She is the author of Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War. Her two most recent books are To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred Year Journey Through China and Korea, from which this article is excerpted, and Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era.

Recommended citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred Year Journey Through China and Korea, 1910-2010,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 46-1-10, November 15, 2010.

Notes

1 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan (New York: Duffield and Co., 1911), 62.

2 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 63.

3 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 63.

4 E. G. Kemp, The Face of Korea, Manchuria and Russian Turkestan (New York: Duffield and Co., 1911) vii.

5 Kemp, Face of Korea, Manchuria and Russian Turkestan, p. xii.

6 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan (New York: Duffield and Co., 1911), 68-69.

7 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 68.

8 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 71.

9 On the Kija myth, see Hyung il Pai, Constructing “Korean” Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology (Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2000).

10 James S. Gale, Korean Sketches (Chicago and New York: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1898), 82.

11 Gale, Korean Sketches, 84.

12 See Heijô Jitsugyô Shinpôsha ed., Heijô Yôran (Heijô [Pyongyang]: Heijô Jitsugyô Shinpôsha, 1909), 17; Kosaku Hirooka, The Latest Guidebook for Travellers in Japan including Formosa, Chosen (Korea) and Manchuria (Tokyo: Seikyo Sha, 1914), 219.

13 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 71-72.

14 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 95.

15 See Steven Hugh Lee, The Korean War (Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd., 2001), 88; Chris Springer, Pyongyang: The Hidden History of the North Korean Capital (Budapest: Entente, 2003), 20.

16 Lee, The Korean War, 88.

17 On street names, see Springer, Pyongyang, 61-62.

18 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 80.

19 Springer, Pyongyang, 39.

20 George T. B. Davis, Korea for Christ (New York: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1910), 20.

21 Kemp, Face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan, 75.

22 On Kang Pan-Seok, see Yeong-Ho Choe, “Christian Background in the Early Life of Kim Il-Song”, Asian Survey, 26, no. 10, (Octoner 1986): 1082-1091.

23 Springer, Pyongyang, 105.