Inoue Hisashi: Crusader with a pen

By Tanaka Nobuko

So wide-ranging are 71-year-old Inoue Hisashi ‘s talents and activities – including playwright, director, novelist, public intellectual and activist, that it is difficult to know which to focus on at the expense of others.

Inoue at east during his recent Japan Times

interview Miura Yoshiaki photo.

Inoue not only writes plays regularly for numerous theaters in Japan, but his own Komatsu-za company that he founded in 1983, and which only stages his plays, is constantly touring the country. He is also a prolific best-selling novelist and has been president of the prestigious Nihon Pen Club since 2003 — as well as being director of Nihon Gekisakka Kyokai (Japan Playwrights Association), director of

Reflecting his irrepressible, often self-deprecating wit, that library’s name is Chihitsu-do, which means Slow-writer’s Hall, since Inoue is well known for not being the speediest of creators. Indeed, because of his “sense of responsibility to the audience,” he is often still rewriting his scripts as the curtain rises.

Looking back, it’s clear to see that the roots of Inoue’s hectic lifestyle run deep.

In the early postwar years, Inoue first got his foot on the literary ladder writing scripts for a striptease theater in downtown

Inoue recently made space in his non-stop schedule to talk to The Japan Times about his work. He talked fluidly and unceasingly, drawing on his wealth of historical knowledge, leavened with witty asides. No doubt his great charm contributes to the busyness of his life, as he is certainly one of those people who acts like a magnet to others.

Why did you become a writer?

My father wanted to be a writer. He ran a pharmacy in a small town in

A scene from Inoue’s “Yumena Namida,” which

follows a family after the mother joins the Tokyo

Trials defense team for accused Class A war

criminals. Yako Masahiko photo.

I was writing hero-story novels when I was 7, but I always got bad marks for composition at school. The teacher asked me why I always wrote made-up stories, and told me that I should write “true” stories from my daily life. After that I intended to be a newspaper journalist as I thought it would be difficult to be a novelist from the beginning. But just then, radio and television were becoming influential, so I became a scriptwriter in those media and started to write plays. Finally, I began writing novels in my 30s.

Why do you mainly write plays nowadays?

Because I realized that since the bubble economy [which “burst” in the early 1990s], people have not been reading novels in their daily lives as before. When my novel “Kirikirijin (The Kirikiri People)” was a best seller in 1981, I saw people reading it on the train and I could get a sense of instant feedback about my work from society. But since the ’90s it has become difficult to get readers’ response to novels.

On the other hand, through theater I can get the audience’s response immediately and directly then and there. Audience members have all taken the trouble to get their tickets in advance and to come all the way to the theater, even these days when everything is normally geared to convenience. Naturally, the audience gets angry if the play is bad, but if it’s good, they thank us in the lobby after the performance.

Also, I am sure that most young people now read younger-generation authors’ books, and it’s probably older ones who read my novels. However, people from all generations — from teenagers to retired people — come to see my plays, so I can address a wider span of society through the theater.

Meanwhile, novels have to be translated, but a good play can be appreciated in other countries even though the language it’s performed in is different, because people can enjoy many aspects, such as the direction and physical expression, the stage sets and lighting and so on — not to mention the acting skills. So I believe theater is more accessible internationally even though we stage it in our own language.

Are you normally involved in the staging of your plays, or do you give any special orders to directors?

In this scene from Inoue’s play “Yume no

Kasabuta,” a family in a remote town in

northern Japan learn they have been chosen to

put up the Showa Emperor for a night during

his postwar national tour.

No. My task is writing the play and I just give my script to the director and say nothing afterward.

Recently, I heard your speech at an event titled “Promoting the renunciation of war by theater people.” What is your opinion on the current nationalistic movement in

Why does the Japanese government not say anything against the

First and foremost,

In article 11 of the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, it says that

So, postwar

Yes, but why does

Well afterward, when

However, in 1978, Yasukuni Shrine secretly enshrined 12 convicted and two indicted Class A war criminals there — so they suddenly became gods. As a result of this, the basis of the postwar fiction disappeared — and the Chinese got angry about this contradiction. The current Yasukuni issue and the problem between Japan and China will never be sorted out without taking this point into account — that China gave up on huge compensation to accept the story that only some people were war criminals, and the rest of the Japanese were victims.

So actually, Japanese governments have had a strong sense of obligation to the

Although that fiction was agreed by international consensus, and the world decided to move forward on that basis, I wonder why Japan forgot about that agreement to blame those 14 war criminals and then enshrined them as gods at Yasukuni and stuck to its own understanding in isolation from other Asian countries.

All my works focus on that point. What was that war? Without searching for the answer to that question, how can we accept responsibility for the war. I experienced militarism when I was small, and the nation became independent when I was a high-school student — so I have seen many of these things myself.

What is the most dangerous weapon in the 21st century? Probably, many people would say nuclear weapons, but I think it’s “information.” Amassing information and being able to sell it and use it and control the timing of when things are revealed — all of these things will be the key weapons in international conflicts.

What do you think about

Now, the relationship between the

It is a similar mentality to Japanese people who believe they won’t have any problems if they get a position at a big company — but I don’t believe that.

There are many first-rate aspects to Japan, such as our culture and food and manga, for instance, and our Constitution has lots of brilliant ideas that are suitable for this 21st century and which many countries look at and admire. We have also been tackling environment pollution since early on, and Japanese companies have been earnestly working to remove pollution in their production processes. So, if

Another good thing about

Why do you write about the effects of the war on

“What was that war to the Japanese?” — that is my lifetime question. I’ve been searching for the answer to that and to discover what it is about Japanese people’s fundamental mentality that brought the militarism about. This task has not yet finished, as the Japanese have not bothered to clarify the root causes or the responsibility for so long as they have hidden behind

When the Cold War finished, the

On the other hand, the only case of Japanese becoming victims involved prisoners of war detained in

It is very contradictory, isn’t it? This two-faced attitude gives

What is the main reason

The main problem is our education system. Japanese children learn

But in practice in

Recently you published a children’s book about the Constitution, and you sometimes you visit schools to give lectures to small children. How do they react to your story?

They understand it so well. The adults, however, don’t listen to my opinion, and they just say it is an idealistic theory. Fundamentally, for example, the idea of the European Union was also said to be a dream idea, but everything sounds like a dream story when it starts. Of course, nothing is achieved by ideals alone, but it’s also no good just going in for “realistic” thinking. The balance of these two elements will make the goal happen in the end.

Your plays not only carry strong messages, often about political and social issues, but they are also high-quality entertainment at the same time.

We take money from the audiences, so first of all we must make them enjoy the play. This is our — theater people’s — job ethic. The most important thing is that every customer/audience member should delight in the play. So many types of people, from normal housewives to old ladies, scholars, politicians and students gather in the theater and share the play, and we must make all of them interested in it.

This is the fundamental theory of the theater but, for example, shingeki [the “new drama movement” that started at the end of the Meiji Era under the influence of Western drama] was part of the social movement, so they emphasized parts that were a bit difficult for the audiences to understand. Well, they may have been very “important” plays, but in my opinion that’s not real theater; that’s a sense of elitism. It’s as if they thought they had a role to advance the stupid masses and raise their intelligence — as if people should see the play even it’s difficult and boring. That’s completely wrong.

There are many dialogues and arguments in your plays, but I also feel the actors throw the questions out to the audiences as well.

Any staging is a quite serious fight between the maker and the audiences. A play should not be done only on the stage, and the words should reach out to every corner of the theater. We have to find the best way to get our message across. So we consider the most effective way of presenting the message, and I compose the lines to let the audiences think naturally during the play about the subjects or themes. This is professional theater people’s work.

One other task, I believe, is for theater people to take responsibility for someone who is visiting the theater for the first time in their life. If that person enjoys the play, she or he will believe the magic of the theater and will continue to go even though the next play may be boring. I feel apologetic toward earlier dramatists such as Shakespeare and the others involved in making theater if I can’t give an excellent experience to that first-time visitor.

Why will people still go to the theater in the 21st century?

Completely different types of people may be standing in line to see the same play at a small venue, but strangely, each person’s thoughts and feelings spread throughout the venue and they share that experience. In the small space, each person becomes related to the others in an invisible chain. Furthermore, that also links to the stage, to the actors, and finally there is a magical moment, a sense of unity and cooperation there. So a good play takes people back to a pure condition, and I see so many people who leave the theater with a bright look like after having a sauna.

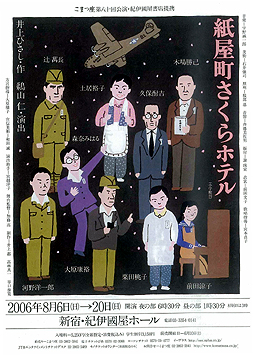

Your recent production of “Kamiyacho Sakura Hotel” was quite different from its successful 1997 staging. Why did you do that?

Poster for Kamiya Sakura Hotel, August

2006 production

It depends on the audiences. Plays change every day they are staged, and after a certain number of stagings the actors become able to adjust to the feeling of that day’s audience. If they sense that many in the audience seem interested in a political matter like the issue of the Emperor’s war guilt, the actors will take the stage more in that direction; while if there are many in the audience who loves jokes and wit, then they can switch direction. So, people liked it because we adjusted the play depending on the structure of the audience each time. We never do exactly the same play; it changes every day. Actually, the audiences are the center of the theater world.

When I went to

What are your future plans?

I have to write a play about

This is top secret: I am planning to make a new play whose characters include Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini and the Showa Emperor — the gigantic dictators in the 20th century. I’ll adjust the story to fit the history as logically as possible and let them meet all together. Because of them and the same trick — reigns of terror — people suffered for a long time. Actually, nowadays the people holding power use the same trick as they control citizens by implanting a sense of terror. So, if I write about the 20th-century dictators, and I search for the fundamental mentality, the play will work for any time.

“Chichi to Kuraseba” was translated into English, German, Russian and Italian, and will soon be staged in

Inoue Hisashi ‘s book “Kodomo ni Tsutaeru Nihonkoku Kenpo (The Constitution We Want to Pass on to Children)” was published by Kodansha in July 2006.

The next production by Inoue’s Komatsu-za company will be an as yet untitled new work by him about the German pacifist, satirist, poet and novelist Erich Kastner (1899-1974). It will run Jan 14. to Feb. 25, 2007 at Kinokuniya Southern Theater in Shinjuku,

Tanaka Nobuko is a freelance drama writer for publications in

On related themes see Roger Pulvers, The Human Condition after Hiroshima: the world of Inoue Hisashi.

and “A Freedom That Rocks the Boat”: Yoji Sakate’s Small Theater.