Suisheng Zhao

Abstract

Introduction

To meet

In contrast, the state-centered approach is based upon neo-mercantilist thinking that relies on bilateral diplomatic contacts with oil producing countries to beef up energy security by the use of national resource and state-owned enterprise investments in overseas energy assets and tight control of exports and imports of energy products. Although market-oriented economic reform has been the direction of post-Mao reforms, the market-oriented approach has not gained momentum in the energy sector because the Chinese leadership has considered

Indeed, energy security is all about maintaining the nation’s strong economic growth, a linchpin to social stability and ultimately the regime legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as well as the foundation for

A state-led global search for energy security

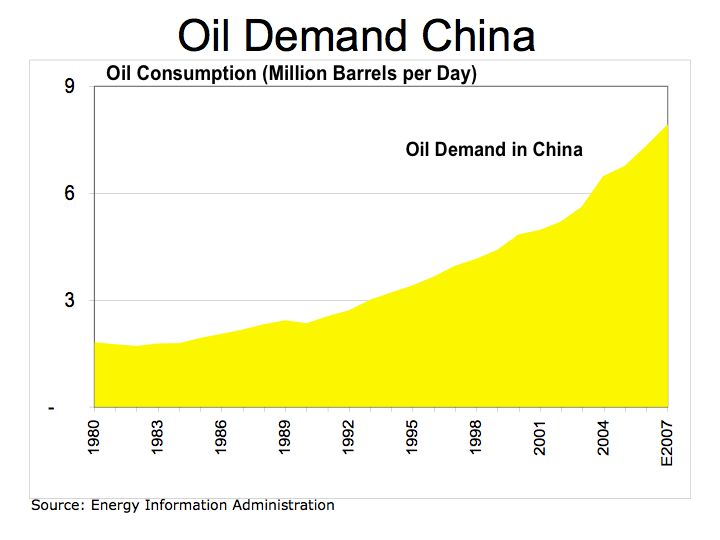

Rapid economic growth in recent years has brought

In the meantime, the state has taken a neo-mercantilist approach to acquiring direct control of overseas energy production and supplies by the state-owned companies. This is to be achieved first through encouraging its giant state-owned energy corporations to acquire overseas assets/companies and lock in supplies of oil and natural resources. While China’s ninth five year plan from 1995 to 2000 called for, among other things, improving energy efficiency by 5% annually, in part by acquiring modern technology, the tenth five year plan in 2001-2005 added a call for seeking international sources of oil and gas. As one indicator of this new strategic move, all three major Chinese oil companies—CNPC, SINOPEC, and CNOOC—have moved quickly to internationalize their operations and expanded into a diverse range of international ventures, ranging from Venezuela to Sudan to Kazakhstan. For example, CNPC in the late 1990s began to transform into a multinational company by building its international subsidiary flagships, CNPC International (CNPCI) and China National Oil and Gas Exploration Development Corporation (CNODC), with overseas production accounting for 60-70% of profits. [10] Since 2003, the company has signed more than 20 contracts to explore or purchase production facilities in 12 countries, including

The corporate investment decisions have been made based on the consideration of the presence of competition from international oil companies and an assessment of political risk as well as technical factors. [12] Although each company has its own corporative objectives and their overseas investments are primarily driven by the companies themselves, the government has tried to help coordinate the companies to make sure that they will not compete against one another for overseas projects and have investment priorities in different parts of the world. [13] To enhance Chinese company’s competitiveness and reduce political risk, Chinese leaders have visited many oil producing countries helping Chinese corporations to secure acquisition deals, and Chinese diplomats have taken advantage of

Gholam Hossein Nozari (R) with the head of China’s Sinopec international arm Zhou Baixiu in Tehran, December 2007 announce a two billion dollar contract to develop a major Iranian oil field

Before the Iraq War in 2003,

This new strategy encourages Chinese state-owned oil corporations to secure investment agreements involving energy exploration, pipelines and refinery facilities with all states around the world that produce oil, gas, and other resources.

A relative newcomer to Latin America,

China’s strategy has alarmed the United States, the world’s largest energy consumer, and raised concerns among some in the US that China is not only challenging the United States’ historic dominance in Africa, Latin America, and Asia but also undermining Western efforts to promote transparency and human rights in these developing countries, damaging US interests and values as China has vied for energy resources in some of the most unstable parts of the world and often ignored the promotion of transparency, good governance and responsible behavior with its partner nations. It is particularly a concern of the

From the Chinese perspective, however, implementation of the diversification strategy has bared fruits. As a Chinese scholar stated, with ‘strengthening international cooperation and diversify energy supplies’ in mind, ‘tapping into energy resources in countries that do not have sound oil and gas infrastructure and helping them establish their own energy industries will bring about a win-win situation where both are able to share the benefits’. [18]

The Asia-Pacific is one crucially important area in which

Energy security was not an issue when

Two policy shifts were significant during the first stage. One was to abandon ideology as the policy guide and to develop friendly relations with neighboring countries regardless of their ideological tendencies and political systems (buyi yishi xingtai he shehui zhidu lun qingsu). The other was to change the practice of defining

The Tiananmen Massacre in 1989 and the subsequent end of the Cold War started the second stage of improvement in

The energy issue became a factor in

First, following the disintegration of the Soviet Union,

Second, China initiated a ‘Treaty of Enhancing Military Mutual Trust in the Border Areas’, which was signed by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan in Shanghai in April 1996, then known as the ‘Shanghai Five’. At its June 2001 meeting in

Third, setting

The acquisition of PetroKazakhstan was feted in

Fourth, making acquisitions and investments in oil fields,

In addition to Central Asia,

Among the mainland Southeast Asian countries,

Although the state-led search for energy security has helped deepen

Disputed areas of Senkakus (Diaoyutai)

Progress towards the settlement of the border disputes has been made largely in the first category. The most important progress is over land disputes with

However, the territorial disputes with several countries along

The

The great power that controls the South China Sea will dominate both archipelagic and peninsular Southeast Asia and play a decisive role in the future of the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean—together with their strategic sea lanes to and from the oil fields of the Middle East. [37]

It is in

Facing these challenging strategic planning issues, the Chinese leaders have found it even more difficult to reach border demarcation agreements or compromises with Southeast Asian countries.

The Chinese foreign ministry also decried efforts by some other Southeast Asian countries to invite multinationals to explore oil and gas in the Spratlys. On 26 October 2004, a partnership of

The dispute between

The energy imperative has gradually changed

It is revealing that when seven Chinese activists shook off Japanese coast guard vessels and landed on one of the islands in March 2004, the Chinese government did nothing to stop these protesters setting sail from a Chinese port. When they were taken into custody by Japanese police and coast guards, the Chinese foreign ministry made official protests. After the seven finally returned to

According to the reporter, the changing position was due to the petroleum imperative, evident in the statement of a leader of the group: they were risking their lives ‘for the sake of our children and grandchildren … the room for existence for the Chinese race will be bigger’ if Beijing could reassume sovereignty over the Diaoyus and exploit their mineral riches. [46]

Both

It is against this background that there has been mounting tension between

A Chinese exploration group started drilling there and plans were drawn up for a pipeline to ship the stuff back to the mainland. As a countermeasure, the Japanese government planned to begin procedures to grant private developers the right to test-drill on the Japanese side of the median line. To add to the sensitivity of the competition, a Chinese nuclear-powered submarine incurred into Japanese waters off the

In addition to these disputes,

Other than the problems with these maritime neighbors,

Conclusion

Armed with foreign exchange reserves approaching $1 billion,

“The results of China’s energy diplomacy are being watched with growing unease, especially in Asia but in other parts of the world as well … There is a danger that China’s neo-mercantilist strategy to bolster energy security by gaining direct control both of oil and gas fields and supply routes could result in escalating tensions in an already volatile region that lacks regional institutions for conflict resolution and is in the midst of a difficult transition process, which is due in fact to the rise of China. Competition for energy is exacerbating existing rivalries between

From this perspective, China’s claim to pursuing a ‘peaceful ascendancy’ policy and putting aside areas of disagreement in favor of creating a stable environment for economic development is limited to areas where China’s vital strategic interests are not threatened. It is not by coincidence that

This article appeared in Journal of Contemporary

Suisheng Zhao is Professor at the Graduate School of International Studies, Executive Director of the Center for China-US Cooperation, University of Denver, and the founding editor of the Journal of Contemporary China. He is the author of China-US Relations Transformed: Perspectives and Strategic Interactions.

Recommended Citation: Suisheng Zhao, “

Notes

1. Christian Constantin, ‘Understanding China’s energy security’, World Political Science Review no. 3, (2007), p. 11.

2. Heinrich Kreft, ‘

3. Willy Lam, ‘

4. Jaewoo Choo, ‘Energy cooperation problems in

5. Zheng Bijian, ‘

6. Erica Downs, The Brookings Foreign Policy Studies, Energy Security Series:

7. Peter S. Goodman, ‘Big shift in

8. ‘

9. Xu Tao, ‘Major Central Asia players: what does a rising

10. Jeff Moore, ‘

11. Goodman, ‘Big shift in

12. Daniel H. Rosen and Trevor Houser, China Energy, A Guide for the Perplexed, China Balance Sheet (a Joint Project by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 2007), p. 30.

13.

14. Ilan Berman, ‘A dangerous partnership’, Wall Street Journal, (22 February 2007).

15. Jim Fisher-Thompson, ‘

16. Drew Thompson, ‘

17. Fisher-Thompson, ‘

18. Xuecheng Liu, ‘

19. Steven I. Levine, ‘

20. You Ji and Jia Qingguo, ‘

21. Suisheng Zhao, ‘The making of

22. Andrew Higgins and Charles Hutzler, ‘

23. Xu Tao, ‘Major Central Asia players’, p. 43.

24. John Keefer Douglas, Mathew B. Nelson and Kevin Schwartz, Fueling the Dragon’s Flame: How China’s Energy Demands Affect Its Relations in the Middle East, Report to US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, (14 September 2006), p. 12.

25. Keith Bradsher and Christopher Pala, ‘Consolation prize for

26. ‘CNOOC Corp. signs Caspian exploration deal’, Washington Post, (8 September 2005).

27. Jonathan Leff and Dominic Whiting, ‘

28. ‘New pact to pipe Kazakh oil to

29. Evan Osnos, ‘The coming fight for oil: the roaring Chinese economy needs more oil’, Chicago Tribune, (19 December 2006).

30. Anon, ‘

31. He Shengda, ‘The water transport network between

32. ‘

33. David Lague, ‘A crucial

34. ‘

35. Lam, ‘

36. John C. K. Daly, ‘Energy concerns and

37. Brad Glosserman, ‘Cooling South China Sea competition’, PacNet no. 22A, (1 June 2001).

38. Osnos, ‘The coming fight for oil’.

39. Kreft, ‘

40. Mark J. Valencia, Hon M. Van Dyke and Noel A. Ludwig, Sharing the Resources of the South China Sea (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1997), pp. 77 and 99.

41. Roger Mitton, ‘

42. Xinhua, (26 October 2004).

43. Valencia et al., Sharing the Resources of the

44. Daly, ‘Energy concerns and

45. Editorial, ‘

46. Lam, ‘

47. ‘

48. Editorial, ‘

49. Chietigj Bajpaee, ‘

50. David Pilling and Victor Mallet, ‘

51. ‘

52. Alela Kornysheva and Evgenia Sokolova Irkutsk, ‘

53. Pallavi Aiyar, ‘Chinese victory parade for PetroKazakh win’, The Indian Express, (24 August 2005).

54. Peter Cornelius and Jonathan Story, ‘

55. Heinrich Kreft,’