Steve Rabson

On March 28, 2008, the Osaka District Court dismissed a lawsuit against Nobel Prize-winning author Oe Kenzaburo and his publisher for publishing accounts of the Japanese military ordering “group suicides” of civilians during the Battle of Okinawa. The plaintiffs, a former garrison commander and the brother of a late former commander, had claimed the descriptions in Oe’s Okinawa Notes (Okinawa Noto, Iwanami Shoten, 1970) and in the late Ienaga Saburo’s The Pacific War (Taiheiyo Senso, Iwanami Shoten, 1968; translation, Pantheon, 1978) were defamatory.

Oe at March 28, 2008 press conference following the verdict

Oe at March 28, 2008 press conference following the verdict

Like his earlier Hiroshima Notes (Iwanami Shoten, 1963; translation, Grove Press, 1996), Okinawa Notes is based on Oe’s visits to a place devastated during the Pacific War, and his conversations with local residents. Hiroshima Notes focuses on prejudice and discrimination experienced in postwar Japan by victims of the atomic bomb, and advocates the abolition of nuclear weapons. Okinawa Notes traces Japan’s oppression and exploitation, starting with annexation of the Ryukyu Kingdom in the 1870s, and examines discriminatory policies toward the people of Okinawa Prefecture, culminating in Imperial Army atrocities against local civilians during the 1945 battle. This work was published two years before Okinawa’s return to Japanese administration in 1972, and one year after the U.S. and Japan negotiated a reversion agreement that, to the bitter disappointment of many Okinawans, left the vast U.S. bases there intact. Oe emphasizes that the prolonged postwar U.S. occupation and military presence, often called “the Okinawa problem” (Okinawa mondai), is more accurately a problem of the U.S. and mainland Japan, which are responsible for creating and perpetuating it.

The court’s verdict came in the wake of the Education Ministry’s 2007 decision to delete references to the Japanese military from descriptions of “group suicides” in school textbooks. The Education Ministry’s decision had earlier ignited the largest demonstration in Okinawan history with more than 100,000 participants. The Asahi Shimbun and both of Okinawa’s daily newspapers, Okinawa Taimusu and Ryukyu Shimpo, praised the court’s verdict for recognizing the validity of testimony by surviving eye-witnesses, and criticized the Education Ministry for basing its decision on the testimony of the plaintiffs, rejected by the trial’s presiding judge as “lacking credibility.” In contrast, a Yomiuri Shimbun editorial disregarded the testimony of surviving eye-witnesses in praising the Education Ministry’s decision to delete “such phrases as ‘the Japanese army forced mass suicides’ [from school textbooks] as long as there is no development regarding the state of historical evidence.” The Ministry had initially sought to eliminate all mention of the Japanese military; only after massive protests in Okinawa and strong objections by the textbooks’ publishers, did it agree to insert the phrase “with the involvement of the Japanese military.” The editorial claimed that “when writer Sono Ayako researched the mass suicides for a book published in 1973, the paucity of evidence supporting the explanation that garrison commanders issued such orders became clear.” It fails to mention, however, that many have questioned the objectivity of Sono’s research, which was based on Japanese military sources and assertions by one of the garrison commanders, especially considering her conclusion that the “group suicides” were “acts of love.” (See Kamata Satoshi, “Shattering Jewels: 110,000 Okinawans Protest Japanese State Censorship of Compulsory Group Suicides,” Japan Focus, January 3, 2008.)

The plaintiffs have appealed the verdict. Compared with local district courts, Japan’s higher courts frequently issue rulings more closely in line with government policies.

Asahi Shimbun, from editorial of March 29, 2008

Court’s verdict acknowledges involvement of Japanese military in “group suicides”

In the Battle of Okinawa late in the Pacific War, the U.S. military made its initial landing in the Kerama Islands west of Naha City. Oe Kenzaburo writes in Okinawa Notes (Iwanami Shoten, 1970) that the group suicides of civilians on Zamami and Tokashiki islands at that time were ordered by the Japanese military stationed there. Umezawa Yutaka (91), former commanding officer on Zamami, and relatives of the late Akamatsu Yoshitsugu, former commanding officer on Tokashiki, claimed that the book’s description was erroneous, and filed a defamation lawsuit against Oe and his publisher seeking 20 million yen [roughly equivalent to $200,000) and a ban on further printing of Okinawa Notes. On March 28, 2008, the Osaka District Court dismissed their suit in its entirety.

Presiding Judge Fukami Toshimasa noted that Japanese soldiers had distributed hand grenades to local villagers, telling these civilians to kill themselves rather than be captured by U.S. forces, and that “group suicides” had occurred only in places where Japanese forces had been stationed. “The Japanese military was deeply involved,” he said. ”It is reasonable to believe that they ordered them.” The court’s verdict was based on the testimony of surviving witnesses and scholarly research.

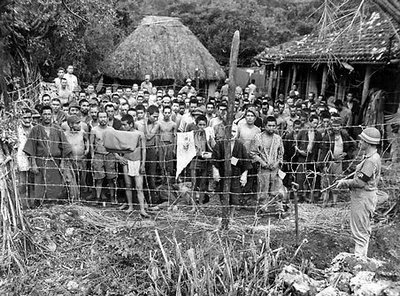

Okinawans under US guard following the battle which took 12,500 American and more than 100,000 Japanese and Okinawan lives

Okinawans under US guard following the battle which took 12,500 American and more than 100,000 Japanese and Okinawan lives

In his book, Oe does not identify either of the commanding officers by name or say they had personally ordered the suicides. In targeting Oe for their lawsuit, the plaintiffs’ purpose seems to have been to undermine the accepted view that the military had ordered them. In an astonishing admission, former commander Umezawa testified in court that he had not read Okinawa Notes until after the lawsuit was filed.

In their testimony, the plaintiffs insisted that the islands’ residents had died for their nation of their own free will “with beautiful hearts,” and that the suicides on Zamami had been ordered by the deputy mayor of Zamami Village. However, the court’s verdict flatly rejected as “lacking credibility” their claim that the order had come from the mayor, and also dismissed their contention that a story about commanders’ orders had been fabricated so the bereaved families could receive war survivors’ pensions.

The court’s verdict aside, the Education Ministry bears a heavy burden of guilt for using the filing of this lawsuit as an excuse to order deletion last year of the phrase “forced by the Japanese military” from descriptions of group suicides in school textbooks. Having based it on the plaintiffs’ one-sided claims, the ministry must now seriously reconsider this action.

In November of 1944, the Japanese military issued a directive that “soldiers and civilians must live and die together.” In Okinawa, all civilians from children to the elderly were mobilized, and told never to become prisoners of war. These were the circumstances in which group suicides occurred.

The Ministry has now permitted insertion of the phrase “with the involvement of the Japanese military” in school textbooks. This verdict reaffirms the undeniable fact that the Japanese military was deeply involved in group suicides.

Asahi Shimbun, March 28, 2008

Reactions to the court’s verdict in the Okinawa Notes case

Today’s verdict of the Osaka District Court acknowledged the Japanese military’s involvement in the tragic group suicides that occurred in Okinawa. Surviving witnesses from Tokashiki Island, who had testified in the case, looked relieved as they commented on the verdict. “We could not allow the rewriting of history.” Former commanding officer Umezawa Yutaka and the other plaintiffs glared at presiding judge Fukami Toshimasa who had announced the dismissal of their lawsuit.

In an interview following the trial, Oe Kenzaburo (73) said, “This verdict indisputably confirms the deep involvement of the Japanese military. Although only the word ‘involvement’ has been restored to school textbooks, teachers can now explain to children the horrible circumstances it signifies.”

In the spring of 1941, the year the Pacific War started, Oe entered elementary school where the militaristic curriculum taught that “No one should live to suffer the shame of becoming a prisoner of war.” After the war, Article Nine of the Constitution, enacted when he was in middle school, became the guiding principle of Oe’s life.

“Future Japanese must never repeat the tragedy of the Battle of Okinawa,” he said today. “Yet, despite the experience of 1945, Japanese have still not overcome the weaknesses of a hierarchical social structure.” Oe published Okinawa Notes in 1970, a tumultuous year of protests against renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. It has sold more than 320,000 copies. A leading author of postwar literature, his activism as a writer has centered on advocating for peace and against nuclear weapons. He was awarded the 1994 Nobel Prize for literature. In June of 2004, he founded the “Article Nine Association” along with philosopher Tsurumi Shunsuke and the late author Oda Makoto. He has lectured widely on the importance of Article Nine and against the deployment of Japan Self-Defense Forces to Iraq.

Last November Oe testified at the trial, responding to questions for three hours on the witness stand. He explained that Okinawans had received an “education to make imperial subjects,” and were forced into a “hierarchical social structure” of military over civilians in which the military forbade anyone from incurring the “shame” of becoming a prisoner of war. Regarding Okinawa Notes, he firmly maintained that “there is no need to change what I have written.”

Shortly before the verdict was announced, Oe wrote in the Asahi Shimbun that “Whether or not there were written or spoken orders is irrelevant to the resulting ‘group suicides.’ Everything about the structure of the Japanese military forced massive numbers of Okinawans to die. . . . I am devoted to preventing a resurgence of the ideology of ‘education to make imperial subjects’ that permeated Japan’s modernization. That is the life-long aim of my writing.”

Yomiuri Shimbun, from editorials of March 29, 2008

Court: Books don’t defame World War II veterans. Army “closely tied to Okinawa mass suicides”

The Osaka District Court on Friday rejected a damages lawsuit against Nobel prize-winning writer Oe Kenzaburo and a publisher brought by a veteran of the Imperial Japanese Army and a brother of a deceased veteran, who claimed descriptions in two books of mass suicides during the Battle of Okinawa were defamatory.

The plaintiffs demanded 20 million yen in compensation and a publication ban on Oe’s Okinawa Notes and The Pacific War by historian Ienaga Saburo, both originally published by Iwanami Shoten press in 1970 and 1968, respectively, on the grounds that the books’ claims that military personnel ordered civilians to commit suicide were false.

Oe’s book does not mention commanding officers Umezawa Yutaka and Akamatsu Yoshitsugu by name. The Pacific War, however, does mention Umezawa directly, saying, “Umezawa ordered [the civilians to] commit mass suicide.”

Presiding Judge Fukami denied the plaintiffs claim, saying: “The army was deeply involved in the mass suicides, so it’s possible to presume the veterans were involved. It’s difficult to readily conclude that the veterans in question ordered [the civilians to commit] mass suicide, but the books’ descriptions have reasonable grounds, and therefore, there is due reason to believe [the descriptions] are truthful . . . .Top-down organizations led by the plaintiffs and others were established on the islands. Therefore, it is possible to presume that [Umezawa and Akamatsu] were involved.”

Recognizing the “deep involvement” of the Japanese army in the mass suicides, the court’s ruling rejected the plaintiffs’ claim. At the same time, the court said it was reluctant to recognize the army’s involvement went as far as issuing orders as described in Oe’s book and ultimately avoided passing judgment on the “order” issue.

Education Ministry’s stance is appropriate

Last year, in the high school history textbook screening case, a passage stating that citizens “were forced by the Japanese army into committing mass suicides” was amended to say they “were driven to commit mass suicides using hand grenades and other means distributed to them with the involvement of the Japanese army.” The opinion formed by an advisory panel to the Education Minister as part of the textbook authorization process was that, as it was not entirely clear whether the army had “forced” the suicides to take place, a decisive description should be avoided. The panel’s position not to permit use of such phrases as “the Japanese army forced mass suicides” as long as there is no development regarding the state of historical evidence seems an appropriate one.

With regard to the mass suicides, for much of the postwar period it has been generally accepted that garrison commanders “ordered” residents to do this. The view is based on accounts given by survivors and local residents, some of which were recounted in the book Tetsu no bofu (Typhoon of Steel), a record of the Battle of Okinawa published in 1950 by the Okinawa Times. But when writer Sono Ayako researched the mass suicides for a book written in 1973, the paucity of evidence supporting the explanation that garrison commanders issued such orders became clear. Taking this view into account, a passage regarding the garrison commanders’ suicide order on Tokashiki Island was expunged in 1986 from The Pacific War, originally published by Iwanami Shoten.

The core point in the trial has been the issue of whether the army issued a specific “order.” The plaintiffs intend to appeal the ruling to a higher court. We will keep a close eye on developments in the higher court.

Okinawa Taimusu, March 29, 2008

Verdict negates Education Ministry’s rationale for textbook revisions

Today Nakazato Toshinobu, Speaker of the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly, called for an early and complete cancellation of previously announced textbook revisions. He noted that the Education Ministry had cited the trial testimony of garrison commander Umezawa Yutaka as its main reason for deleting references to the Japanese military in descriptions of “group suicides.” Now the Osaka District Court has determined that Umezawa’s testimony was not credible. With its major premise undermined, the Ministry has lost its rationale.

“Their troubled souls can now rest in peace.” Bereaved families on Tokashiki Island express relief.

After hearing the verdict announced, several of the families bereaved by the “group suicides” gathered to pray at the local memorial to the victims. “This verdict calms the troubled souls of our families and relatives who died.” Minamoto Keisuke (69), six years old at the time, survived because a grenade at the site failed to detonate. “Obviously, the residents of Awaren Village gathered there because the Japanese military ordered it. The voices of people in Okinawa must continue to be heard,” he said. “Considering it was a time when the military arrogantly wielded their total authority, it is only natural that the verdict recognized their involvement,” said Murata Takayasu (85), President of the Senior Citizens Association.

A woman traces the name of deceased kin at memorial service following the verdict

A woman traces the name of deceased kin at memorial service following the verdict

Okinawa Taimusu, from editorial of March 29, 2008

Verdict affirms historical fact

A key point of this verdict is that it recognizes the importance of testimony by surviving eye-witnesses. In 1982, the Education Ministry sought to delete references in school textbooks to the killings of civilians in Okinawa by the Japanese military. The Ministry claimed that, because descriptions of the killings in books on Okinawan history were “stories of people’s experiences” (taiken-dan), these books did not qualify as research works (kenkyu-sho). This excuse represents the worst kind of documentarianism (bunsho-shugi). Documents are valuable as historical sources, but it is impossible to know the actual circumstances of the Battle of Okinawa by relying on them alone. The text of this verdict, which draws on extensive interviews and written materials collected by researchers of the Battle of Okinawa, can serve as a standard explanation of “group suicides.”

Political motives explain timing of lawsuit

Oe’s Okinawa Notes was published in 1970, two years before Okinawa’s reversion to Japan. So why a lawsuit now? We cannot help suspecting a political connection between the lawsuit’s filing and the textbook revisions announced last year. It was when the Education Ministry’s panel was in the midst of drafting the revisions last August that a close associate of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo in the Diet gave a speech announcing that “masochistic views of history will be identified and revised by the Prime Minister.” The panel cited the lawsuit, then being contested, in denying the military’s coercion, and recommended textbook revisions. The court’s verdict makes it clear that the panel acted rashly.

Ryukyu Shimpo, March 29, 2008

Verdict recognizes importance of war survivors’ eye-witness testimony

Few written documents survive the chaos of war. This is why the testimony of surviving eye-witnesses is so valuable. Clearly, it played a decisive role in determining truth and falsehood about the Battle of Okinawa in this trial.

This verdict cleared the name of the late Miyazato Morishige, former deputy mayor of Zamami Village, and brought relief to his relatives. The plaintiffs claimed that he had issued the order for villagers to commit “group suicide.” Surviving witnesses testified that the order had come from the military, and the verdict explicitly rejected the plaintiffs’ contention as “without credibility.”

Ryukyu Shimpo, September 10, 2007

Surviving eye-witness testifies to Japanese military coercion of “group suicides”

Judges from the Osaka District Court arrived in Naha yesterday to hear testimony of surviving eye-witnesses to “group suicides” during the Battle of Okinawa. Kinjo Shigeaki (78) testified this afternoon that Japanese military coercion was involved. A former president of Okinawa Christian Junior College, Kinjo was sixteen years old in March of 1945 when 329 residents of Tokashiki Island lost their lives, including his mother and younger brother.

Ryukyu Shimpo, May 25, 2007

Medoruma Shun connects lawsuit and textbook revisions to U.S. and Japanese military policies

Author Medoruma Shun, speaking at a symposium in Osaka, warned that “this lawsuit and the textbook revisions must be viewed in the context of the build-up in Okinawa of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. Recently, for the first time, S.D.F. units were deployed there to facilitate base construction in Henoko. The aims of the lawsuit and the textbook revisions are to undermine the view of the Self-Defense Forces held in Okinawa and Japan as a whole, based on lessons learned from the Battle of Okinawa, that military forces do not protect people; and, to elicit residents’ cooperation in war waged by the U.S. and Japan together.”

Japan Focus associate Steve Rabson compiled and translated all the excerpts above except those from the Yomiuri Shimbun which publishes its own translations of editorials. He prepared this article for Japan Focus. Published on April 8, 2008.

Rabson is professor emeritus of East Asian Studies, Brown University, the author of Righteous Cause or Tragic Folly: Changing Views of War in Modern Japanese Poetry, and a translator of Okinawan literature.

See also

Steve Rabson, Okinawan Perspectives on Japan’s Imperial Institution

Roger Pulvers, Landmark case spotlights ‘Japanese-style nationalism’