The Axis of Vaudeville: Images of North Korea in South Korean Pop Culture

Stephen Epstein

Summary

This paper examines how South Korean understanding of what it means to be—or to have been—a citizen of the DPRK has evolved during the last decade. How does South Korean popular culture reflect that evolution and, in turn, shape ongoing transformations in that understanding? These questions have significant policy implications and take on a heightened salience given the recent deterioration in relations that has taken place under the Lee Myung Bak administration: is the South Korean imagination being enlarged to make room for an inclusive but heterogeneous identity that accepts both parts of the divided nation? Or, conversely, is a hardening of mental boundaries inscribing cultural/social difference in tandem with the previous decade’s (anything but linear) progress in political/economic rapprochement? In examining these questions, I sample key discursive sites where the South Korean imaginary expresses itself, including music, advertising, television comedy programs, film and literature.

Certainly, as widely noted, policies of engagement have led to noteworthy changes in the South’s images of North Korea. Prior to Kim Dae Jung’s presidency, South Korean popular representations of the North were one-dimensional, depicting it generally as a demonized object of fear or contempt. North Korean characters were almost inevitably presented as spies or terrorists—cardboard caricatures of evil incarnate, or, at best, brainwashed automatons, victims of the state. Recent years have added, if not finely nuanced representations, at least a broader array of hues to the palette from which depictions of the North are drawn. In the discussion I highlight significant but less noted developments.

I concentrate on an important but little noticed trend in the South’s imagining of North Korea since the turn of the millennium. Dealing with the DPRK is of course serious business, and its nuclear program and chronic food shortages dominate media images of the country outside of the Korean peninsula. In the last decade, however, South Korean cultural productions have often treated the North in modes that draw on comedy, irony or farce in preference to more straightforward, solemn readings. This partially reflects a broader post-modern turn in Korean popular culture, but one might hypothesize that the ironic mode has also become a strategy for dealing with a growing sense of heterogeneity on the Korean peninsula. If North Korea is no longer viewed as an evil portion of the South Korean Self, but rather simply another country (albeit with a special relationship to South Korea), the South Korean imaginary becomes freer to treat these differences as humorous rather than threatening.

Introduction

Just over ten years ago, in 1998, Roy Richard Grinker published his important book Korea and its Futures: Unification and the Unfinished War. Grinker, bringing to bear keen anthropological insight and a fresh comparative perspective, argued persuasively that the South Korean nation exhibited a collective desire to maintain the dream of unification rather than achieve it. In his cogent analysis, South Korea has wished to continue imagining a homogenous Korea without confronting dissonant evidence to the contrary about its alienated sibling to the North. For Grinker, the general ignorance of most South Koreans about the everyday life of the North Korean people has allowed North Korea and a unified Korea to function in the Southern imagination as (1998: xi) “blank slates open to fantasy and projection”; moreover, in his analysis, a resultant discourse of homogeneity (tongjilsŏng) disrupted by national division has functioned as a stumbling block to unification.

Much has changed, however, since Grinker’s book appeared, and his thesis deserves re-examination ten years on. Increasing contact with the North and its people has rendered South Korea’s neighbor more familiar but attitudes towards it more complex.[1] Despite the souring of the North-South relationship that has occurred since Lee Myung Bak assumed the presidency in February 2008, a decade of the Sunshine Policy, the partial demystification of the North that accompanied it, and the momentous 2000 summit meeting between Kim Jong Il and Kim Dae Jung have all contributed to popular Southern reassessments of North Korea and North Korean identity. Amidst a trajectory of increased interaction, in 1998 Hyundai Asan began tours to scenic Mount Kǔmgang, extending them in late 2007 to Kaesŏng, just across the border from Seoul. Although shepherded away from direct contact with the citizens of Kaesŏng, for the first time South Koreans in large numbers observed a North Korean city at close quarters.[2] In addition to the 1.9 million South Korean tourists who set foot on North Korean soil before the tours were suspended last year, roughly half a million North and South Koreans visited each other’s country for official and semi-official purposes in the last decade, in contrast to a figure of 2980 for the entire 1989-1997 period.[3] Equally significantly, by 2007 the number of former North Koreans in the South, whether one prefers to term them t’albukja (“refugees from the North”) or saet’ŏmin (“new settlers”),[4] surpassed 10,000 and they now form a substantial minority within the Republic of Korea (ROK). There has thus been exponential growth in the number of South Koreans who either have firsthand experience of the North or have met those who grew up in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

Critical as well to a change in the South Korean imagination of North Korea, but perhaps less immediately obvious, are important internal developments in South Korean self-understanding. Since the turn of the millennium, such factors as the Korean Wave, success in the 2002 World Cup, and global leadership in digital technologies have dramatically reconfigured the South’s sense of its place in the region and in the world; simultaneously, greater labor migration and a phenomenal spike in international marriage are altering the ethnic makeup and consciousness of South Korea itself.[5] Despite any nostalgia one might find for a purer Korean “essence” untainted by globalization, the South enjoys an unassailable confidence in the superiority of its system to that of the North.[6] Popular perceptions of the dangers the North poses to South Korea have focused in recent years more on its potential to inject instability by suddenly imploding or igniting a conflict with the United States than as an ideological menace.

In this paper I consider how South Korean understanding of what it means to be—or to have been—a citizen of the DPRK has evolved during the last decade. How does South Korean popular culture reflect that evolution and, in turn, shape ongoing transformations in that understanding? These questions have significant policy implications in light of Grinker’s earlier argument: is the South Korean imagination being enlarged to make room for an inclusive but heterogeneous identity that accepts both parts of the divided nation? Or, conversely, is a hardening of mental boundaries inscribing cultural/social difference in tandem with (anything but linear) progress in political/economic rapprochement? In examining these questions, I offer a diverse sampling from key discursive sites where the South Korean imaginary expresses itself, including music, advertising, television comedy programs, film and literature.

Certainly, as widely noted (cf. Lee 2007: 58; Kim 2007; Kim and Jang 2007), policies of engagement have led to noteworthy changes in the South’s images of North Korea. Although always subject to partial contestation, prior to Kim Dae Jung’s presidency, South Korean popular representations of the North were one-dimensional, depicting it generally as a demonized object of fear or contempt, with North Korean characters almost inevitably spies or terrorists—cardboard caricatures of evil incarnate, or, at best, brainwashed automatons, victims of the state. Evidence of evolution became particularly apparent with the blockbuster movies Shiri (1999) and Joint Security Area (JSA) (2000), which put a more human face on North Korean adversaries. These films have drawn a great deal of attention (see, e.g., Kim 2004: 257-276; Kim 2007), and I do not dwell on them here.

Recent years have added, if not finely nuanced representations, at least a broader array of hues to the palette from which depictions of the North are drawn, and in the discussion that follows I wish to highlight significant but less noted developments. I concentrate on an important trend in the South’s imagining of North Korea since the turn of the millennium: dealing with the DPRK, as widely conceded, is serious business, and its nuclear program and ongoing food shortages often dominate media images of the country outside of the Korean peninsula. In the last decade, however, cultural productions from South Korea have often treated the North in modes that draw on comedy, irony or farce in preference to more straightforward, solemn readings. This partially reflects a broader postmodern turn in Korean popular culture,[7] but one might hypothesize that the ironic mode has also become a strategy for dealing with a growing sense of heterogeneity on the Korean peninsula. If North Korea is no longer viewed as an evil portion of the South Korean Self, but rather as another country and one with a special relationship to South Korea, the South Korean imaginary becomes freer to treat these differences as humorous rather than threatening.

Dancing at the DMZ

Let me begin with an intriguing case study. In 2006, observers of the South Korean music scene may have noted a surprising entry in K-pop’s continual search for fresh sensations: the industry’s appetite for local equivalents of the Spice Girls—which has currently achieved an apotheosis in the Wonder Girls—led to the debut of the Ǔmaktan (the “Wild Rocambole Band,” as at least one source has translated it).[8] Composed of five women who had trained as musicians and dancers in the North and who had arrived separately as refugees in the South, the Ǔmaktan came together in the hope of finding success in the competitive local pop scene. Although high-profile defector Kim Hye-Young has made a career as an entertainer in the South, the Ǔmaktan are thus far the lone case of a saet’ŏmin “girl group” or “boy band.” The members of the band played up their Northern origins as their comparative advantage and attracted a modicum of press attention, both domestically and internationally (Yi ǔn-jŏng 2006). In sporadic television appearances, they performed songs that drew on North Korean shinminyo (“new folk ballad”) stylings and a heavy t’ǔrŏt’ǔ (“trot,” an older form of Korean pop music) influence. Despite an initial minor flurry of media interest, however, the group has already disappeared more or less from view.[9] Although the band’s musical talent won admirers, ultimately the Tallae Ǔmaktan is a novelty act within contemporary South Korean society, and, as with novelties, interest waned once the period of novelty wore off.

Nevertheless, the Tallae Ǔmaktan’s very existence and its lighthearted and self-referential fusion of North Korean identity and South Korean popular culture merit attention. In particular, the band’s video for their catchy tune Mŏtchaengi (“Sharp Dressed Man”), with its parodic homage to memorable scenes from JSA and 2005’s Welcome to Dongmakgol, raises questions about reconstituted understandings of the North.[10] Far from dwelling on dark or melodramatic images of North Korean refugees, the music video takes a playful approach; to be a t’albukja, it tells us, does not automatically mean to be somber.

The Video for Motchaengi

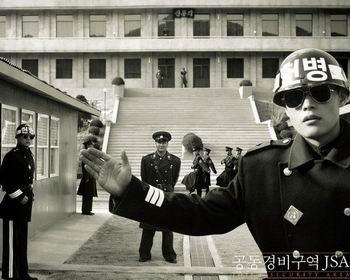

Directed by O Se-hun and using a set created for JSA, the video opens with perhaps the canonical image of direct North-South contact: Panmunjom. The camera gazes northward across the demarcation line, capturing in the frame Southern soldiers from behind, while a North Korean officer goosesteps across the background to the rear of two North Korean guards at the line. The initial shot, as might be expected, thus encourages the audience to share a Southern viewpoint. Meanwhile, however, a red scroll unfurls down the screen with the band’s name in a font style that clearly suggests North Korea, as accordion music, equally evocative of North Korea, plays at a muted level. Inset in this introductory sequence is a small split screen where an announcer declaims in an exaggerated tone. His heavily reverbed voice, reminiscent of propaganda broadcasts, is punctuated by a high-pitched shriek and exaggerated gestures. Although unquestionably introducing the band, his words are muffled and distorted, rendering comprehension difficult. Nonetheless, one can make out snatches of phrases mixed incongruously such as the Northern “chosŏn inmin tongmu” (North Korean comrades), “nyŏsŏng tongmu” (“female comrades”), alongside Southern preference for naming the two countries (i.e. “nambukhan” for South and North Korea, where the North would prefer a form with “chosŏn”). Just before he finishes, the camera’s point of view reverses and is that of the north. We now see the Ǔmaktan, in plain black and white hanbok (traditional Korean dress), looking down on the scene from The Freedom House Pagoda and gesticulating toward the soldiers. The mélange of camera viewpoints, linguistic input and a quasi-surreal situation destabilize any ready interpretive framework.

The scene then shifts, and the song proper begins. As the band sings lyrics that pay tribute to the fashionable love interest of the title, we focus on Northern and Southern guards confronting one another. In a less amicable replay of JSA, one soldier berates the other because his counterpart’s shadow falls over the line, and the two then spit at each other in an escalating challenge. Fellow soldiers rush to them and guns are drawn. Interspersed with this threatening imagery, however, are shots of the soldiers from both sides dancing in unison along with the band and gazing at them with longing, one of them even doing push-ups at their feet in an amusing display of testosterone-fueled swagger. The band members thus appear as both objects of desire and a force for reconciliation.

An abrupt cut away offers a second vignette that again recalls JSA. Here we witness an abbreviated reenactment of the scene in which the Southern protagonist steps on a mine while out on patrol and is rescued by his Northern counterpart, again intercut with shots of the Tallae Ǔmaktan performing, still at Panmunjom. In Mŏtchaengi, however, although the detonator is removed and the mine evidently defused, immediately before the song’s shouted “hey” signals the end of the first chorus, the mine blows up along with the soldier in an unexpected moment of black humor.

The second verse, which repeats the lyrics of the first, then shifts to a set that recalls Welcome to Dongmakgol. We find ourselves in a traditional rural village at a tavern. Three Southern soldiers are drinking with the villagers when three Northern soldiers arrive, led in by a young woman, reprising Kang Hye-Jŏng’s prize-wining turn in the film as a slightly unhinged girl. Guns are again drawn, and the opposing soldiers once more appear in confrontation, as in the film. The young woman twirls before them pushing the guns away with an utter lack of concern, and the villagers merrily continue their drinking, while the soldiers remain poised to attack one another. Yet again, the scene is interspersed with shots of the Ǔmaktan performing, now in ornate hanbok, and beckoning to the camera in winsome fashion. As the song moves to its end, the standoff yields to a sequence of cheery ensemble dancing, with Northern and Southern soldiers stepping along side by side, the villagers behind them, in a spirit of unity. And as the first half of the video ends with an explosion, so too does the second conclude with an accidental detonation. The young woman nonchalantly hurls live ammunition into the air, but instead of returning to earth as shrapnel, it descends as popcorn, recapitulating one of Welcome to Dongmakgol’s most remarkable moments.

Viewers might well ask themselves: just what is going on here? How are we to make sense of this video and its mischievous take on contact between North and South? Of course, the generic conventions of music videos, with their penchant for rapid cutting and edits, often make it difficult to reconstruct linear, or even logical, narratives from them. To attempt to do so here is perhaps even more fruitless than usual, given the postmodern pastiche of its intertextual allusions. Rather, we might say that the video presents a fantasy realm that allows for the free play of imagination. We encounter not merely the surreal, but also a spirit of Aristophanic revelry or even quasi-Bakhtinian carnival that upends rigid political structures in favor of collective release, as figured in its images of drinking, eating, dancing and singing. Military aggression is mollified through indulgence in bodily pleasures, and via the Ǔmaktan, who mediate between North and South in their capacity as entertainers, as border crossers, and as women, a point to which I will return momentarily.[11] The band occupies a liminal space, flush against the boundary between a past within the DPRK and a present in the ROK. This liminality is explicitly symbolized by their performance on the Southern side of Panmunjom, the demarcation line visible just a meter behind them.

The Ǔmaktan at the DMZ

Indeed, the use of Panmunjom as the setting in which to introduce the band, and the DMZ motif throughout, indexes changing representations of the North-South relationship. Panmunjom offers a particularly fruitful site for artistic manipulation because it encapsulates literally an interface between North and South: the two sides stare each other down, present within the same space across a clear dividing line. After years of commentators pointing to the oxymoronic name “demilitarized zone,” to the extent that noting the incongruity had become a cliché, we are witnessing a genuine demilitarization of the zone in South Korean pop culture, such that it forms a setting for humorous play. Diaspora Korean Brandon Lee, for example, also makes fine use of the JSA set for Panmunjom in his Planet B-Boy sequence “Run-DMZ,” in which Korean breakdancing crews, costumed as Northern and Southern soldiers, square off against each other in a spirit of competition that resolves as intra-Korean solidarity.[12] The distorted mirroring effect between North and South that occurs at Panmunjom can now be treated as if it belongs to a geopolitical fun house.[13]

The Run-DMZ sequence from Brandon Lee’s Planet B-Boy

Mŏtchaengi and Planet B-Boy also suggest the extent to which South Korean images of the North are being articulated in an intertextual form. That is, South Korean pop culture is now self-reflexively engaging with a history of portrayals of the North and differing visions of the nature of a divided Korea. Mŏtchaengi and Planet B-Boy allude directly to the already canonical JSA, but also comment more obliquely on a half-century’s tradition of representations and the malleability of these representations. Just as hegemonic, top-down interpretations of the North have been challenged from below in the South, North Korean refugee and diaspora subjectivities are now sculpting the contours of these representations as well.

A canonical DMZ shot from Park Chan-wook’s JSA

Planet B-Boy homage to JSA

Namnyŏ pungnyŏ

That the Tallae Ǔmaktan simultaneously embodies aspects of Self and Other as a saet’ŏmin band makes their contribution to South Korean popular culture particularly noteworthy. In coming to grips with the unusual spectacle the band presents, commentators have regularly invoked a discourse of homogeneity, seasoned with enticing difference. As one reporter remarks (Yi Chae-won 2006), “Other than their Northern accent and way of speaking, there is nothing that distinguishes the members of the Ǔmaktan from young women of the South.“ Similarly, a Yonhap News story (Anonymous 2006) notes with surprise that in making the video for Mŏtchaengi the members of the band wore komushin (gumshoes) for the first time, but that their grumbling over how the flat shoes make them look shorter is precisely what one would expect from South Korea’s shinsedae (new generation).[14] Similarly, in self-description, the band members and those who work with them contrast cultural aspects of the North and South, but identify a desire to meld the two. For example, Im Kang-hyŏn, the composer of Mŏtchaengi, states that “some think that North Korean music is backwards (ch’onsǔrŏpta), but in fact it has a high degree of artistic accomplishment. We want to demonstrate a fusion of North Korean artistry and the South’s ease and refinement.” The comment, appearing in Yi Chae-won’s (2006) article “Tallae Ǔmaktan: We Want to Convey the Fragrance of Unification,” gives pause for thought: while the discourse of unification often stresses the recovery of lost homogeneity, North and South are also often simultaneously set apart with complementary qualities, not simply because of ideological difference and not always to the detriment of the North.

This notion of the complementarity of North and South has, of course, long played a role in an important realm: the four-syllable set phrase namnam pungnyŏ (lit. Southern man, Northern woman) helps shape perceptions that the ideal Korean couple brings together a man from the South and a woman from the North. The aphorism has appeared as the title of two films,[15] in a 2008 KBS radio sitcom that stars Im Yu-gyŏng of the Tallae Ǔmaktan, and now crops up in matchmaking services, such as “Namnam pungnyŏ kyŏrhon k’ŏnsŏlt’ing” (“Southern Man, Northern Woman Marriage Consulting”),[16] whose owner is a saet’ŏmin woman. The increasingly high percentage of women among North Koreans now in the South as a result of lopsided demographics in the North Korean refugee population,[17] the stir created by the North Korean cheerleaders at the Taegu Universiade in 2003 (see e.g. Faiola, 2003; Sohn 2003), and the increase in international marriages of Korean men to women from elsewhere in Asia have all likely played a role in maintaining the durability of the phrase. Although the maxim itself predates national division,[18] it also may now suggest in gendered terms a hierarchical relationship between the nations and how (Grinker 1998: 51) ”as the two Koreas diverge, south Korea takes on the role of metaphorical colonizer to north Korea as metaphorical Other.”

Nonetheless, this widespread metaphorical equation of gender and hierarchical national relations is undergoing a complex evolution on the Korean peninsula. The Tallae Ǔmaktan itself underscores the ongoing importance of the North to South Korean discourses of gender. In a piece about them that includes the phrase “namnam pungnyŏ” in its title only to dismiss it (Anonymous 2006), a band member is quoted as saying, “The whole idea that it’s men in the South and women in the North is out of date. South Korean women are really pretty” (namnam pungnyŏ ta yetmal. namhan yŏjadǔrǔn nŏmu yeppŏyo) The last decade has seen an increasing differentiation in the South’s imaginings of paradigms of feminine beauty in North and South, with the North promising purity in contrast to Southern sexiness. The Ǔmaktan appropriates such a mantle of purity in explaining the band’s name (Yi Chae-wŏn 2006): “the fresh plant that gives off the fragrance of spring from frozen ground is none other than the tallae….we want to give our South Korean fans a sense of comfort and purity like that of the tallae.” Indeed, the concept of innocent purity (sunsuhada), with its positive and nostalgic view of qualities associated with a lack of sophistication, appears in a variety of Southern contrasts: between its own rural and urban inhabitants, between a developing Asian hinterland and the developed South Korea, and between North and South (cf. Grinker 1998: 171). Band members draw further implicit distinction between themselves and South Korean female stars in discussing their choreography (Anonymous 2006): “We’re seeking after a classical dancing style. Actually, we don’t know much about South Korean dance, but Lee Hyori and Chae Yeon seem to dance well.”

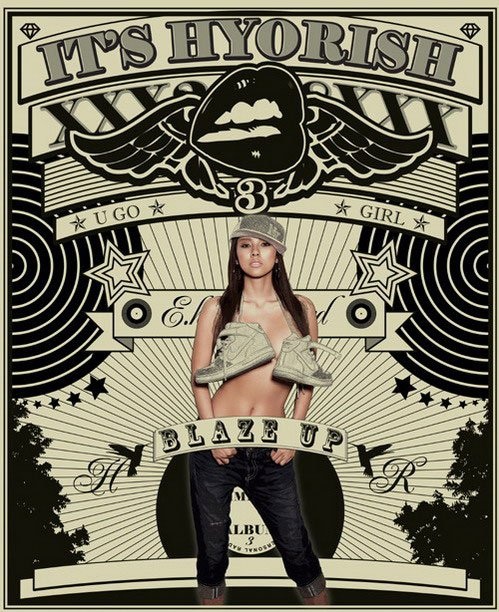

The contrast in dancing styles between the Tallae Ǔmaktan and the South Korean stars mentioned could hardly be starker. K-pop megastar Lee Hyori, whose latest album title knowingly declares, with an in-your-face pun for English speakers, “It’s Hyorish,” stands as symbol par excellence for the increasingly provocative sexuality of South Korean popular culture.

Lee Hyo-ri’s most recent album “It’s Hyorish”

Strikingly divergent modes of idealized Northern and Southern femininity underpin a 2005 ad campaign for Samsung Anycall’s video mobile phone technology that pairs Lee with North Korean dancer Cho Myung Ae.[19] In the series, the two are performing in Shanghai in a joint South-North concert. They are first seen in the concert hall, each surrounded by a media crush, and make longing eye contact as they pass each other in the midst of their entourages without exchanging words. A dramatic voiceover (whose breathiness even carries quasi-erotic overtones) says, “You can speak without speaking. Just from looking, your pulse can race. Digital Exciting. Anycall.”

The opening sequence of the Lee Hyori/Cho Myung Ae Samsung Anycall ad campaign

In a sequel, Lee sends a satellite DMB phone as a gift to Cho in her dressing room. We then see Cho on stage, in elegant hanbok and gyrating with a vase on her head, an accomplished classical dancer. Cho’s performance is juxtaposed with shots of Lee in her own dressing room, clad in jeans and a top that exposes her midriff, practicing a few dance moves. The camera allows fleeting glimpses of the overtly sexual grinding of her hips, affirming Lee’s iconic status among contemporary South Korea’s foremost sex symbols. Lee and Cho then hold a joint press conference in which Lee asks her counterpart’s age, and, upon hearing the answer, notes that she is Cho’s “big sister” (ŏnni). In a final segment, we view the two spending the day together, holding hands, and exchanging gifts before departing with a promise to meet once more. The campaign, notable for its rare depiction of interaction between South and North Korean women, hints at a sisterly bonding akin to the intense homosociality of JSA (see Kim 2004: 266). I would argue, however, that while the ad foregrounds the possibility of a warm relationship between the two, it equally emphasizes flagrant contrast. South Korean popular culture, while at times encouraging belief that North and South can develop close friendship, also increasingly highlights a gulf that extends beyond obvious ideological difference to fundamentally opposed modes of acculturation.

Sisters? Lee Hyori and Cho Myung Ae

The Axis of Vaudeville

In a similar vein, a trio of 2003 B-film comedies aimed at South Korea’s youth market all imagine romantic couplings between North and South and engage in explorations of complementarity and difference. Namnam pungnyŏ, Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyǔn kanch’ŏp and Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani (respective English titles: Love Impossible, Spy Girl, and North Korean Guys), in their use of humor and caricature, decline to be taken seriously, but this refusal of earnestness paradoxically deserves to be considered seriously as an indicator of a sea change in the South Korean imaginary. Although prior to the 2000 summit one occasionally finds jollier treatments of the North in South Korean popular culture (e.g. 1999’s Kanch’ŏp Ri Chŏl-jin; English title: The Spy), the meeting between Kim Dae Jung and Kim Jong Il thrust the North into new territory: that of romantic farce. The triggering of optimism about inter-Korean relations made it possible to find in the North a source of fun and romantic reveries, and filmmakers eagerly exploited the opportunity.

Namnam pungnyŏ (English title: Love Impossible), in tackling head-on the putative ideal Korean match, sets the clash between North and South in execrably ludicrous (even offensive) terms. The film follows the “impossible” love story between Ch’ŏl-su, a handsome university student from the South who is an incorrigible and not terribly sympathetic womanizer, and Yŏng-hǔi, a beautiful and academically talented young woman from Pyongyang. The two meet in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Northeast China, where they are taking part in a joint North-South excavation project on Koguryŏ tombs. In the movie’s farcical calculus, however, Yŏng-hǔi exhibits an odd mixture of ethereal femininity and masculine toughness: in Ch’ŏl-su’s first sighting she has an artlessly radiant beauty, but she later displays an astonishing capacity for alcohol and her martial, acrobatic dancing style causes onlookers’ jaws to drop. Although she displays ideological fervor, demurring on her budding relationship with Ch’ŏl-su by saying she still has much to do for her country, she also shows potential corruptibility: she listens to rap music on the sly in Pyongyang, her Northern sidekick convinces her to visit a disco in Yanbian, and she readily turns to makeup when given the opportunity. The film seems torn between portraying her as alien and suggesting that North Korean girls, like their Southern peers, just wanna have consumerist fun. The tension between centripetal and centrifugal forces towards similarity and difference drives much of the film’s humor.

Namnam pungnyŏ – an Impossible Love?

Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyǔn kanch’ŏp likewise portrays a romance between a Southern young man and a beautiful woman from the North, whose angelic demeanor here belies the fact that she is a tough-as-nails spy. While both Nannam pungnyŏ and Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyǔn kanch’ŏp apparently wish to emulate the success of recent forerunners that featured forbidding women as the protagonists in romantic comedies, such as 2001’s Chop’ok manura (My Wife is a Gangster) and Yŏpkijŏgin kǔnyŏ (My Sassy Girl), the Northern element adds a crucial twist: the female protagonists are not treated so much as exceptional individuals as representatives of an exceptional nation. Nonetheless, the North Korean “Spy Girl” clearly evokes audience sympathy in contrast to the film’s “bad” Southern characters. The latter include not only gangsters but venal and vain young women, who can only be enticed on dates at the price of expensive eye shadow. Indeed, a striking feature of this set of films is the discourse they open about South Korea itself, and the frequency with which this framework is turned to the South’s detriment. For example, the clash of the South’s growing sexual openness and the North’s more traditional restraint has become a stock trope, but handling of this motif can vary greatly depending on the needs of the moment: the North can be seen as enticingly innocent or hickish; the South, suavely sophisticated or decadent.

Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyǔn kanch’ŏp – “Spy Girl”

The premise of Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani is that two sailors in North Korea’s Navy are blown off course and wind up in the South. The film’s title derives from the sailor’s names, Ch’oe Paek-tu and Rim Tong-hun, and, in quoting the opening line of the South Korean national anthem referring to the East Sea and Mt. Paektu, suggests the film’s patent aspirations to tap into allegories of unification. Again, however, culture clash drives comedy, as when circumstances lead the protagonists into performing a rap song, and the viewer witnesses the incongruous spectacle of North Koreans mimicking the most Westernized aspects of contemporary South Korean popular culture. When the pair first recognize from a vantage point on a bluff above an East Coast beach that they have arrived in the ROK, the film shifts into a montage of attractive young men and women in skimpy swimsuits, public displays of affection, families playing in the water, and joyous dancing beside a boom box surrounded by cans of Hite beer, all set to a rock-and-roll soundtrack. The two Northerners stand motionless, jaws agape.

Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani – “North Korean Guys,” strangers in a strange land

Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani recapitulates numerous features of Nannam pungnyŏ and Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyǔn kanch’ŏp, the primary difference lying in its reversal of the usual formula of Southern man and Northern woman. Captain Ch’oe Paek-tu is portrayed sympathetically as a dashing, if muttukttukhan (brusque) lead. He is a skilled fighter, in touch with the natural world, and exhibits chivalry. His favorable qualities impress a troubled young South Korean woman with the unsubtle name Han Na-ra (“Grand Nation” or “One Nation”), and affection develops between the two. At the film’s conclusion, the two North Koreans depart for home in a dinghy and Ch’oe Paek-tu and Han Na-ra share a sentimental farewell, promising that when they meet again they will be able to be friends. The film thus offers a frothy concoction of allegory-lite for the popular market, offering the hope that “Nara” might be reunited with “Paektu.” But some implicit assumptions should not escape the viewer’s attention: first, the locus of the Korean nation naturally resides within South Korea and unification thus signifies reabsorbing territory that belongs with it. Moreover, in projecting a happy ending for its Northern protagonists, the film sends them to a third destination:[20] because the North is no longer suitable for them after their taste of Southern pleasures, and the South can not yet accommodate them, their boat is once more blown off course, and this time they wash up on a tropical beach. In the film’s final moments, Hawaiian-inflected music plays and two bikini-clad Caucasian women, holding cocktails, walk by and give them come-hither smiles, at which point the credit roll begins.

The film pictures life in South Korea, then, as desirable, but desirable for an open leisure culture that includes the right to relax and admire scantily clad bodies at the beach, not for political concepts such as freedom and democracy. Indeed, these films often emphasize oppressive aspects of South Korean society, and Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani portrays figures representing both the law (the police and the military) and the lawless (gangsters) as infringing on the life of common citizens. Likewise, Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyǔn kanch’ŏp, as noted, also features gangsters, and Ch’ŏl-su in Namnam pungnyŏ must confront an overbearing professor. Additionally, he receives a slapstick roughing-up from his authoritarian father, who, it turns out, is no less than the director of the National Intelligence Service. Conversely, in treating the North Korean political system as endearingly quirky rather than inhuman,[21] this set of films aligns North Korea more closely with an axis of vaudeville than an axis of evil. The use of humor thus takes on an implicit political and moral dimension: rejection of anti-Communist rhetoric in these films humanizes North Koreans at one level; however, in rendering Northerners appealing, the films also entrench them as Other.

While one might therefore debate whether South Korea’s recent delight in finding the North a source of comedy represents a step forward for inter-Korean relations, the comic mode itself can be applied in different directions. In 2002, Korea’s premier comedy program, KBS2’s long-running Kegǔ k’onsŏtǔ (Gag Concert), ran a set of skits featuring the Kkotbonguri yesuldan (Flower Bud Art Troupe).[22] The series involved a group of women in North Korean-style hanbok singing slightly twisted children’s songs, and the segment’s affectionate humor suggested naïve but lovable country cousins. By September 2008, however, a new set of Kegǔ k’onsŏtǔ skits had begun, featuring the Taep’odong yesulguktan (Taep’odong Art Theatre Troupe). Instead of flowers, the name references North Korea’s ballistic missiles, and the show’s more mean-spirited jibes come across as a throwback to an earlier era of virulent anti-Communist ideology.

The segment’s appearance in 2008 with the election of Lee Myung Bak is unlikely to be a coincidence, whether we are witnessing a desire to pander to the current government’s essential abandonment of the Sunshine Policy or a reflection of a new national mood in dealing with North Korea. Each segment has members of the troupe performing before a laconic Dear Leader, who gives commands to the two military figures who flank him. The troupe’s vignettes vary in content each week, but one constant has been a lesson on North Korean sat’uri (dialect) that has purported natives of Hamgyŏng and P’yŏngan Province demonstrating the niceties of expression in their locales. The show plays on negative stereotypes about Northerners as dirty, cruel and, despite being socialists, mad for money. The segment also slights North Korean masculinity. Thus, the “translation” of “I want to sleep with you” in Hamgyŏng dialect becomes “I’ve washed up,” while in P’yŏngan, it is “Don’t move or I’ll shoot.” Likewise, we’re told that, in order to lure a woman, in Hamgyŏng one says “We’ve got a color TV,” while in P’yŏngan it is simply “tie her up.”[23]

Stills from the Taep’odong yesulguktan segment of Kegǔ k’onsŏtǔ depicting Kim Jong Il

The Sopranos in Seoul

If, however, the broad brushstrokes of television comedy can favor a view of North Korea that is relentlessly stereotypical, literature offers the possibility for far more sophisticated treatments, by allowing us to share in the detailed imagining of a North Korean character’s thought processes. As a final case study, let me briefly consider Kim Young-ha’s 2006 novel Pitǔi Cheguk.(Empire of Light), perhaps the most significant South Korean novel of the new millennium to involve a North Korean character.[24] The extent to which a Northern identity has become “good to think with” is evident in the compelling premise of this novel by Kim, widely regarded as the finest literary light of his generation: the protagonist Ki-yŏng is a North Korean spy who has been in the South since the mid-1980s and assumes that he has been forgotten since he has had no communication from the North in a decade. Over the years he has become assimilated into South Korean life as an indie film distributor, with a former student activist wife and a daughter now attending junior high school. Suddenly, however, he is summoned to return within twenty-four hours, an order that has no possibility of being contravened. Aside from the thought-provoking existential implications of the novel (how does one confront the knowledge that in twenty-four hours one’s life will essentially come to an end?), the text presents Kim’s intriguing meditations on the process of identity formation and re-formation for a North Korean embedded in South Korean society. Not only do these meditations offer penetrating insights into the meaning the North holds for contemporary Korean society, but the North itself becomes a vehicle through which to explore the changes that the South has undergone over the last generation.

Kim brings an urbane, ironic sensibility to his writing. Indeed, given the almost obsessive namedropping of cosmopolitan pop culture touchstones in his work, one suspects that he may have been influenced by the acclaimed HBO TV series The Sopranos, which, with cool detachment, portrays the family of a Mafia don as a suburban New Jersey family. Similarly, Kim tries to envision a North Korean spy as part of a typical Seoul nuclear unit, but he brings with him a fin-de-siècle, or perhaps better, début-de-millénaire, take on South Korean society. Kim, shunning moralization, instead clinically portrays South Korean decadence: Ki-yŏng’s wife takes part in an explicit threesome with her university student lover and one of his male friends; his co-worker is addicted to internet pornography, and his daughter’s best friend is known around school for having flashed her breasts to a boy via a webcam.

While the various case studies I discussed above use North Korea as a simple mirror to reflect the attractions and excesses of contemporary South Korean consumer culture, Kim offers a more thoughtful and incisive view of the role that consumer choice plays in establishing contemporary Southern identities. Ki-yŏng has, in fact, managed to adapt successfully enough that his first impulse upon receiving the order to return are to select a few books and his iPod. Likewise, a former lover attempts to dissuade him from obeying the order to return to the North by denying that he can still have allegiance to the Party and the Dear Leader. For her, Ki-yŏng’s Southern identity is proven because he is an individual who can be defined in terms of consumption choices (cf. Lee 2007: 59):

I know you. You like fugu-infused sake, sushi, and Heineken. Sam Peckinpah and Wim Wenders movies. You love Camus’ novel where Meursault kills an Arab. You underline elegant passages in the writing of the gay reactionary Mishima Yukio. You have seafood pasta for Sunday brunch, and on Friday nights, you drink scotch at bars near Hongik University. Right? (Kim 2006: 289)

However, Ki-yŏng remains an eternal immigrant and an outsider. While he does not experience crippling angst, he cannot escape a quotidian anomie that results from the additional Northern identity that he brings with him. Having lived now over twenty years in the South has neither allowed him to re-establish a coherent sense of self, nor to bridge the chasm of difference that yawns between the North Korea he grew up in and contemporary South Korean society. This alienation is likewise figured in pop culture terms:

Gi-yong didn’t have the cultural experiences they took for granted from childhood. He grew up without knowing about King Kong and Mazinger Z, Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, Donald Duck and Woody Woodpecker, Superman and Spiderman. Steve McQueen’s Papillon and The Great Escape were on TV every holiday in the South, but he only studied them much later on video. He had no choice but to watch Gone With The Wind and Ben-Hur on cable. He didn’t recall when Cha Bum-gun dominated the Bundesliga or the huge sensation caused by pop stars Kim Chu-ja and Na Hoon-Ah. At Liaison Office 130, he memorized facts week after week and was quizzed on them, but he only learned these items with his head. He could give the right answers but couldn’t feel their meaning in his heart. It made him think of himself as a cyborg composed of circuits and microchips. He knew more about Cho Yong-pil and Aster and Seo Tae-ji than anyone, and he could rattle off the history of pro baseball and the student movement in the 1980s, but that knowledge didn’t fill his emptiness. (Kim 2006: 102)

In the world of South Korea in the new millennium, with its endless consumer choice, Ki-yŏng thus experiences himself as less than human:

He took off his watch…It was plated with 14K gold, unfashionable now. Unfashionable? Making fashion judgments that easily felt alien. In the world in which he grew up, having your own standards for beauty and ugliness was the most dangerous sort of adventure. At some point without his even noticing it his eyes, heart, and hard disk had been completely transplanted for this world, as if he were a rewired cyborg. (Kim 2006: 78)

In Kim’s imagining, then, even an intelligent, well-trained North Korean who has now spent half of his life in the South cannot achieve a sense of national belonging in contemporary South Korean society; the rejection of an idealized sense of Korean homogeneity is here almost complete.

Kim also provides a crucial insight for understanding how the possible recovery of tongjilsŏng has come to be lost, however. Much of the novel is concerned with a contrast of the days of student activism in the 1980s and the gulf that separates it from South Korea in the first decade of the twenty-first century (cf. Lee 2007). Ki-yŏng in fact notes that the South Korea of the 1980s shares more with the DPRK of the 1980s than with the South Korea of today:

Jobs generally came with a lifetime guarantee and university students almost never worried about their futures. Banks and conglomerates had their lobbies fitted out with imported marble, and they seemed like eternal institutions. Children supported their elderly parents and parents held authority over children. The president was chosen in an indirect election that took place in a gymnasium. He won with overwhelming support, and the opposition existed only in name. Most people had little interest in the outside world. The North’s motto, “Let’s Live Our Way,” seemed equally applicable to the South Korea of the 1980’s. (Kim 2006: 198)

As the commitment of 1980s activism has yielded to consumerism, so too the goal of recovering an imagined lost Korean homogeneity recedes ever further into the distance, and perhaps unification with it. The growing problem, in this reading, is not so much that North Korea is an idiosyncratic and isolated outlier in the world system, but that South Korea itself has diverged from its own inherited Korean identity and become the Other to its past Self. In a key passage in Empire of Light, Ki-Yŏng recalls getting together with fellow North Korean spy Jong-hun to watch the 2002 Word Cup. As they sit in front of his 40-inch color TV, drinking beer, they cheer on South Korea’s performance:

As Park Ji-sung knocked the ball in from right in front of Portugal’s goal, they both leaped up from the couch spontaneously, cheering. But when Park ran over to the bench and jumped into Guus Hiddink’s arms, Jong-hun’s joy subsided. He sat back down and gulped some beer. “I just can’t get it. What do they need a foreign coach for? The players dye their hair, and the coaches are foreigners. How can you say that this team represents Koreans?”

Gi-yong didn’t agree, but he didn’t bother to argue the point. Nationalism, especially in the North, was the very lifeblood of politics. Gi-yong thought that someday the personality cult around Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il could be dismantled, but that a sense of nationalism would live on much longer. (Kim 2006: 133-34)

In other words, North Korea’s current regime need not stand forever. Nonetheless, its frequently avowed commitment to an ethnically pure (in a different sense of sunsuhada) and more rigid vision of Korean identity may prevent it from achieving solidarity from a radically reconfigured South, where Korean identity now embraces and even necessitates cosmopolitan belonging.

Conclusion

In conclusion, let me return to the difficult, even unanswerable, question that I posed at the beginning of this essay: is the South Korean imagination being enlarged to make room for an inclusive but heterogeneous identity that accepts both parts of the divided nation? Grinker, writing just before the Sunshine Policy was put into place, stated presciently that (1998: 222) “it is possible that the master narratives are changing, and anecdotal evidence from scholars working in Korea indicates that many people are beginning to discuss more explicitly the potential problems of unification.” Certainly, in the last ten years discussion and recognition of such problems has become widespread, and there are those who will publicly challenge the sacred Korean cow that is unification.

But popular culture opens a view to surprising twists in response to my question. At the conclusion of his study Grinker (1998: 269) wrote that he found it troubling that “Koreans do not employ a concept of difference that evokes the positive sense of a melting pot or multiculturalism often found in European and North American societies. Difference is assumed to be negative.” What Grinker could not have foreseen is the extent of South Korea’s diversification over the last decade. Although perhaps no one would argue that South Korea consistently propagates a positive sense of a national melting pot, a discourse of multiculturalism, albeit contested and far from universal, is emerging, and doing so with top-down support.[25] Paradoxically, however, it is this increasing sense of cosmopolitanism in South Korea and the enlarging of the South Korean imagination that in future years may function as a critical, and perhaps insurmountable, stumbling block to re-imagining the homogenous nation again, for this more inclusive heterogeneity is now diluting the pre-eminence of North Korea in the national imagination, as South Korea gropes tentatively toward a vision of national belonging based more on citizenship than ethnicity.

Increased marriage migration to South Korea and a surge in the number of offspring from these marriages is confronting the long-cherished notion of the tanil minjok (“unitary race”) with a serious challenge. This new migration is especially remarkable for being particularly widespread in the rural heartland, precisely in that sector of the nation where South Korean discourse most often holds that its version of the “real Korea” still resides. Popular culture is responding to this demographic trend in intriguing ways. Consider for a moment Sadon ch’ŏǔm poepkessǔmnida (Meet the In-Laws). The show, which debuted in 2007 as a segment on the show Iryoil chot’a (Happy Sunday), brings together the families of couples in international marriages for a first meeting and is clearly a well-intentioned attempt to humanize the numerous foreign brides who have taken up residence in Korea and to promote intercultural understanding generally. As journalist Kim Tae-eun writes, “The greatest virtue of Meet the In-Laws is that it causes us to meditate on the homogeneity (tongjilsŏng) of the peoples of Asia.”[26] The show thus fosters a growing regional identity, but Kim’s comment also raises a crucial conundrum: if South Korea can extend its imagination of homogeneity to the peoples of Asia, what does this mean for South Korea’s tongjilsŏng with North Korea? As the number of South Koreans in international marriages rises steadily, South Korea becomes more entwined within a regional web, and an increasing sense of difference, if not necessarily enmity, with the North is emerging. Despite South Korea’s ties of blood, language and history to the North, is it possible that North Korea might be jostled from its pre-eminent position in the South Korean imagination so that it becomes simply another country?

A running joke in Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani has the Northern protagonists mistaken as Chosŏnjok, ethnic Koreans from China. A similar confusion occurs in the 2006 film Kukkyŏng-ǔi namtchok (Over the Border), and Yanbian, the center of the Chinese-Korean community, assumes a special importance in Namnam pungnyŏ as well. These pop cultural assimilations deserve attention: what does it mean for North Koreans to be framed as members of a Korean diaspora community rather than an integral part of a singular (South) Korean nation? The “Koreanness” of the Chosŏnjok is not denied. Indeed, one often finds the notion that they retain aspects of a Korean past more successfully than South Koreans themselves, as, for example, when noted travel writer Han Biya (1998b: 319) includes a photograph that offers visual proof that ‘our past’ remains intact on Chinese soil in the grass-roofed farm houses of Yanbian (uriǔi yetnarǔi kosǔranhi namaittnǔn yenbyenǔi nongch’on ch’oga). Their “South Koreanness” is, however, far more problematic. The South Korean nation’s significantly increased exposure in recent years to those with whom they share ethnicity but not necessarily a similar outlook has led at times to friction: Chinese-Koreans have often found themselves treated as second class citizens in South Korea and South Koreans have discovered that many Chinese-Koreans feel a greater allegiance to the PRC than a larger Korean nation.[27]

Consider too that in several of the cultural products I have cited in this essay, I have noted women wearing hanbok, such as the Tallae Ǔmaktan, Cho Myung Ae, the Kkotbonguri Yesultan, and the Taep’odong Yesulgǔktan. What, one might ask, could be a more quintessential image of “Koreanness”? At no point, however, in any of these texts do we see or hear of a South Korean woman wearing hanbok. Compare instead the appearance of the boy band Shinhwa in the 2003 “Concert for Unification (t’ongil ǔmakhoe) held in Pyongyang. On stage before a cutout backdrop in the shape of the Korean peninsula, they performed their song “Perfect Man,” which, in addition to its English title, mixes English and Korean lyrics. The band wore obviously Western-influenced garb, and incorporated Western-derived dance moves. The North Korean audience reaction ranged from polite boredom to bemusement to disdain. The clip, if I may offer an opinion, is hilarious, but clearly not by intention.[28]

South Korean boy band Shinhwa performing in Pyongyang

Chogukǔn hanada. So runs a well-known 1980s piece by activist South Korean poet Kim Nam-ju. And so it may be: “Korea” and its homeland may still be one. Longing for unification in the South has hardly evaporated completely. In this essay I have not dealt with a more recent subset of films that foster sympathy for the plight of North Korean refugees such as Kukkyŏng-ǔi namtchok, Chŏǔm mannan saramdǔl (Hello, Stranger; 2007) and K’ǔroshing (The Crossing; 2008). But even such films suggest that North Koreans will struggle to be assimilated into the South Korean national fabric because of the extent to which contemporary South Korea takes part in a globalized form of late-capitalist consumer culture. It appears that South Korea and its national imagination are increasingly able to incorporate a form of North Korean identity. The more difficult issue may be whether North Korean identity can accept South Korea and its national imagination in the 21st century.

This article is an expansion of a paper originally prepared for the North/South Interfaces in the Korean Peninsula conference held at l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris in December 2008. The author would like to thank the participants in that conference, as well as the referees of the Asia-Pacific Journal, for helpful feedback.

Stephen Epstein is the Director of the Asian Studies Programme at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. He has published widely on contemporary Korean society and literature and has also translated numerous works of Korean and Indonesian fiction. His co-translation with Yu Young-nan of Who Ate Up All the Shinga?, an autobiographical novel by Park Wan-suh (Pak Wan-sŏ), will appear on Columbia University Press in July 2009.

He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal. Posted on March 7, 2009.

Recommended citation: Stephen Epstein, “The Axis of Vaudeville: Images of North Korea in South Korean Pop Culture” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 10-2-09, March 7, 2009.

Sources

Burghart, Sabine and Rüdiger Frank. 2008. “Inter-Korean Cooperation 2000-2008: Commercial and Non-Commercial Transactions and Human Exchanges, Vienna Working Papers on East Asian Economy and Society 1: 1, 26 pp.

Grinker, Roy Richard. 1998. Korea and Its Futures. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Haggard, Stephan and Marcus Noland. 2006. The North Korean Refugee Crisis: Human Rights and International Response. Washington: U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Available at

Han Biya. 1998. Paramǔi ttal: kŏrŏsŏ chigu sebak’wiban 3. Seoul: Kǔmt’o Tosŏch’ulp’an.

Hwang Jongyon. 2007. “A Postmodern Turn in Korean Literature.” Korea Journal 47.1: 5-7.

Hwang Sŏk-yŏng. 1993. Sarami salgo issŏttne. Seoul: Shiwasahoesa.

Kang, Yŏng-suk. 2006. Rina. Seoul: Random House JoongAng.

Kim, Andrew Eungi. 2009. “Demography, Migration and Multiculturalism in South Korea.” The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Kim, Jih-Un and Dong-Jin Jang. 2007. “Aliens Among Brothers? The Status and Perception of North Korean Refugees in South Korea,” Asian Perspective 31:2: 5-22.

Kim, Kyung Hyun. 2004. The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Kim Suk-young. 2007. “Crossing the Border to the Other Side: Dynamics of Interaction between North and South Koreans in Joint Security Area and Spy Li Chul-jin,” in Frances Gateward, ed., Seoul Searching: Culture and Identity in Contemporary Korean Cinema (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007): 219-242.

Kim Young-ha. 2006. Pitǔi Cheguk (Empire of Light). Seoul: Munhakdongne.

Lee Hye-Ryoung. 2007. “The Transnational Imagination and Historical Geography of 21st Century Korean Novels,” Korea Journal, 47.1: 50-78.

Nam, Christine. 2008. “Brothers or Strangers?: The Re-identification of South Korea and the North Korean Refugee Other,” paper presented at 4th World Congress of Korean Studies.

Song, Changzoo. 2007. “Chosonjok between China and Korea: The Zhonghua Nationalism, De-territorialised Nationalism and Transnationalism,” The International Journal of Korean Studies 4: 75-102.

Newspaper articles

All internet sources accessed on 16/11/2008.

Anonymous. 21/7/2006. “Myubitchijǔn Ǔmaktan ‘uri kopge bwa chuseyo: nanam pungnyŏ yetmal, namhan yŏjadǔl nŏmu yeppŏyo” (The Ǔmaktan on the Video Set: ‘Southern Man, Northern Woman Is Already Dated, Southern Girls Are Really Pretty”)

Faiola, Anthony. 8/9/2003. “What Do They Want in South Korea? Unification!” Washington Post, p. A1

Kim Tae-ǔn. 25/12/2007. Sadon ch’ŏǔm poepkessǔmnida. Imi uriga doen oegugin myŏnǔridǔl (Meet the In-Laws: Foreign Daughters-in-Law Who Are Already Part of Us)

Kim ǔn-hye, 1/10/2002. “Ajikto uri minjokǔl pogo usǔshimnikka?” (Do You Still Laugh At Our Fellow Koreans?).

Lee, Sung-Jin, 4/11/2008. “South Korean Films Not Popular Anymore[sic] in North”, The Daily NK.

Sohn Jie-ae, 9/9/2003. “Shock Over Korean Beauties’ Rage.”

Yi Chae-wŏn,. 18/7/2006. Ǔmaktan ‘t’ongilǔi hyangi chŏnhallaeyo.’ “Ǔmaktan: We Want to Convey the Fragrance of Unification”,

Yi ǔn-jŏng , 11/7/2006. “Oeshindo kwanshim t’albbuknyŏ ‘pantchak kǔrubiranyo!’ (The Poreign Press’ Interest in the Northern Refugee Women: ‘They’re a Sparkling Group!’ “ )

Filmography

Chop’ok manura [My Wife is a Gangster], 2001. dir. Cho Chin-gyu.

Chŏǔm mannan saramdǔl [Hello, Stranger] . 2007. dir. Kim Tong-hyŏn {Kim Dong-hyun].

Kanch’ŏp rich’ŏljin, [The Spy], 1999, dir. Chang Chin.

Kongdonggyŏngbiguyŏk: JSA [Joint Security Area: JSA], 2000, dir. Pak Ch’an-uk [Park Chan-wook].

Kukkkyŏngǔi namjjok [Over the Border]. 2006. dir. An Pan-sŏk..

Kǔnyŏrǔl morǔmyŏn kanch’ŏp [Spy Girl], 2003, dir. Pak Han-jun.

Kǔrŏshing [The Crossing]. 2008. dir. Kim Tae-kyun.

Namnambuknyŏ [Love Impossible], 2003, dir. Chŏng Ch’o-shin.

Swiri [Shiri], 1999, dir. Kang Che-gyu.

Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani [North Korean guys], 2003., dir. An Chi-u [Ahn Ji-woo].

Welk’ŏm t’u tongmakkol, [Welcome to Dongmakgol], 2005. dir. Pak Kwang-hyŏn [Park Kwang Hyun].

Yŏpgijŏgin kǔnyŏ [My Sassy Girl ], 2001. dir. Kwak Chae-yong [Kwak Jae-yong].

Notes

[1]See Burghart and Frank, 2008 for a good précis of the significantly increased contacts in recent years.

[2]Visitors to Kaesŏng itself had reached 100,000 by October 2008. See “Gaeseong Visitors Top 100,000,”

[3]Ministry of Unification figures on Human Cooperation cited in Burghart and Frank (2008: 19).

[4]For more on the issues of nomenclature, see Nam (2008: 8).

[5]On these latter issues, see Andrew Kim (2009), “Demography, Migration and Multiculturalism in South Korea.“

[6]Cf. Lee (2007: 58): “In terms of popular culture, at least, it is no longer possible for the North to invade the South; rather, the North is seen as being captured by capitalism.”

[7]Cf . Hwang (2007: 5-6) on literature: “the literature of commitment and moral virtue has been superseded by a detailed exploration of everyday life.”

[8]Anonymous, “New girl band has talent and a North Korean past in common.”

[9]Member Im Yu-gyŏng has maintained a higher public profile, releasing a solo album, collaborating with other performers, and occasionally appearing on variety shows such as Star Golden Bell. Most notably, in 2008 she took on a lead role in a KBS radio sitcom entitled Namnam pungnyŏ, for more on which see below.

[10]This video is available for viewing online in several places including here and here. The latter also carries the song’s lyrics.

[11]That the Ǔmakdan carries a notion of carnival with it is supported by the choice of popular rap artist MC Mong to have member Im Yu-gyŏng do a vocal portion for his track “Circus.” The artist has gone on record as saying that he did so because her North Korean vocal style enhanced the old-fashioned circus flavor of his material.

[12]For an online clip, see this.

[13]The set of Panmunjom is also used in a sequence in Tonghaemulgwa Paektusani that offers one of the film’s more amusing conceits. A third sailor marooned with the title characters hopes to defect but is unceremoniously thrust back across the line with a perfunctory apology from the Southern security apparatus: “We’re sorry, but the economy is really bad right now, Come back when things are better.” They then fob him off with a parting gift of Orion sweets (a popular South Korean brand), and he dashes across the line ostentatiously shouting praises to the Kims.

[14]Cf. Yi ǔn-jŏng (2006):: “With their baseball caps and body-hugging pants with mini-skirts worn over them, their style is no different from any 20 year old of the new generation. Only their pronunciation of “s” and “o” and their accent gives away a Northern origin.”

[15]In addition to the film analyzed below, Pak Sang-ho directed a 1967 film by that title.

[16]See this.

[17]In addition to the unfortunate truth that North Korean women in China know that they have they have their bodies to sell if they become desperate, women in North Korea have taken a more active role in trading and have been more active than North Korean males in developing coping strategies. For more on these issues, see Haggard and Noland (2006).

[18]The phrase is first used in 1927’s Chosŏnyŏsokko by Yi Nǔng-hwa. For more, see an article by Kim Chi-hyŏng on “namnam pungnyŏ” on the website “uri mal iyagi,”

[19]Portions of this ad campaign sequence may be viewed in multiple places online, including here and here.

[20]One may be tempted to see the influence here of Choe In-hun’s seminal novel Kwangjang (The Square), which similarly sends its protagonist to a third destination after he experiences life in both North and South, although such a highbrow literary reference may sit uneasily with the film’s lowbrow tastes.

[21]The primary exception occurs with the goons of Namnam pungnyŏ, who are sent by Yŏng-hǔi’s father, himself a figure high in the DPRK military hierarchy, to break up the relationship. But even here Ch’ŏl-su eventually has a chance to make his case before none other than Kim Jong Il himself.

[22]On the Kkotbonguri yesuldan, see this.

[23]For a sample of the Taep’odong yesulgǔktan, see this. One can find a taste of the contested reaction to the Taep’odong yesulgǔktan here and here.

[24]Mention should be made of Kang Yŏng-suk’s 2006 novel Rina, winner of the Han’guk Ilbo’s literature prize. This fascinating but idiosyncratic text never explicitly identifies its protagonist as a North Korean refugee, however, and the t’albukja Rina never arrives in “country P,” which appears to stand for South Korea. Instead, Kang seemingly uses her protagonist to explore the idea of an eternally wandering diasporic, stateless subject.

[25]See Kim (2009).

[26]See Kim Tae-eun (2007).

[27]For more on these issues, see Song (2007). In particular note the disgusted reaction of the woman at 3:10-3:13. For a recent piece that suggests the declining popularity of South Korean DVDs in the North, see this.

[28]In particular note the disgusted reaction of the woman at 3:10-3:13. For a recent piece that suggests the declining popularity of South Korean DVDs in the North, see here.