Stephanie Bangarth

Because the overwhelming majority of us are innocent, we protest against restrictions based on our racial ancestry; we protest against the fine technical distinctions of word and deed to cloak the facts; we protest against the arbitrary judgments on our loyalties; we protest against the indifference to and disallowance of our human qualities . . . all because we happen to be of Japanese descent.

“Racialism is a Disease,” Nisei Affairs (January 1946)

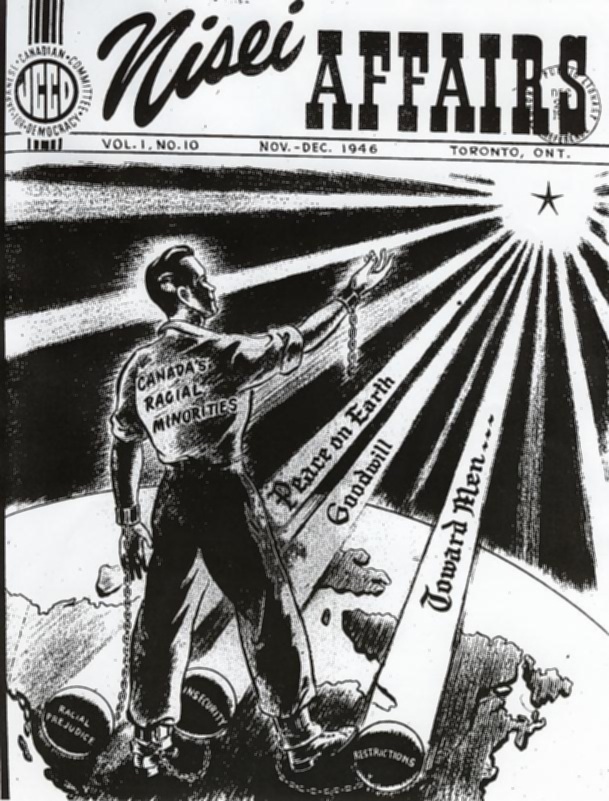

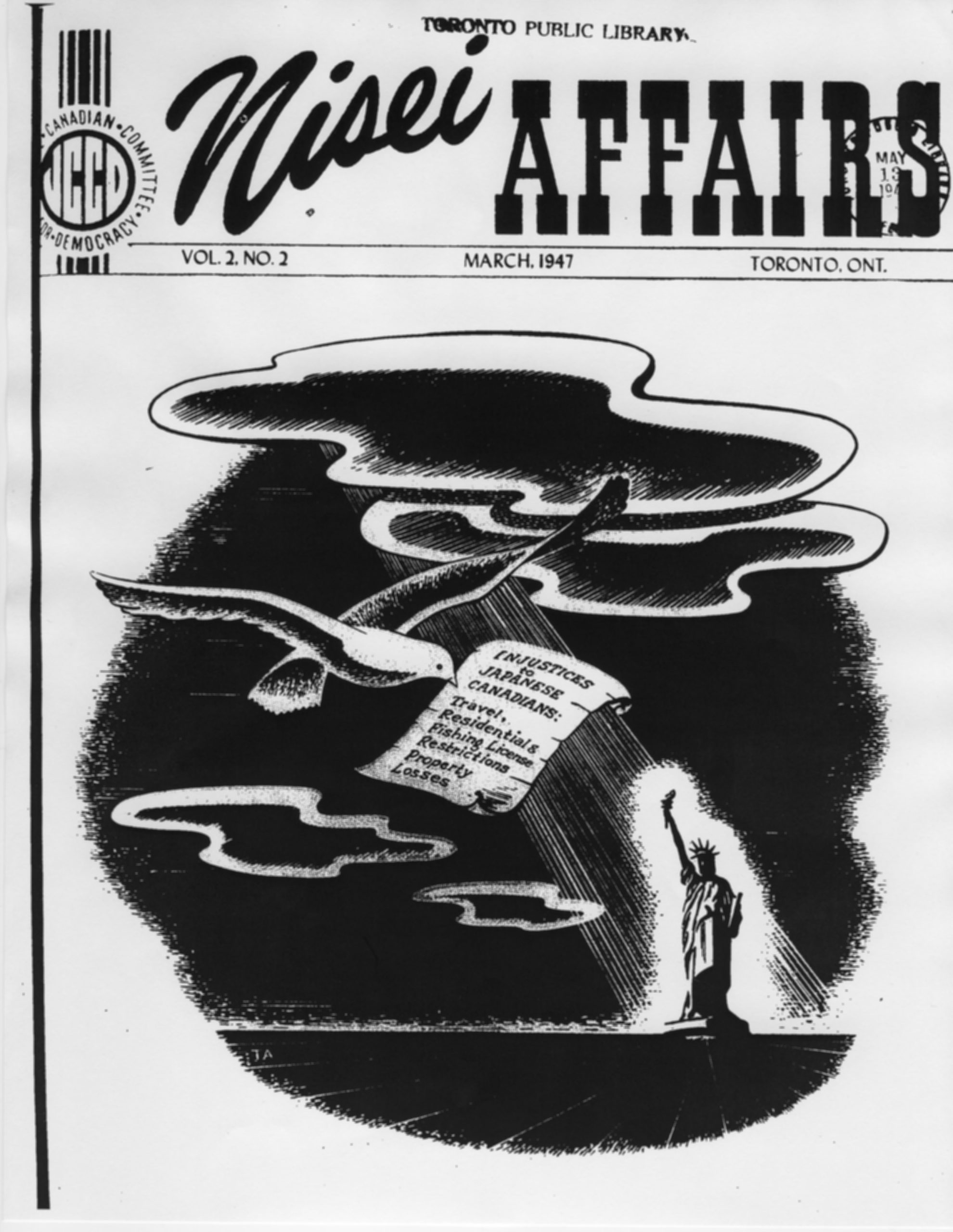

From 1945 to 1947, Muriel Kitagawa wrote numerous articles exhorting the Japanese Canadian community to respond to injustice, not unlike the call to action above. She believed that, if those who advocated the denial of Nikkei (persons of Japanese ancestry in North America) rights remained unopposed, other groups would soon feel the sting of oppression with the wholesale curtailment of their human rights. Although the leading Canadian and American public advocates for the Nikkei were almost exclusively white males from religious or professional backgrounds, they were not alone. American and Canadian Nikkei did not sit passively while others defended their rights over the course of the Second World War and beyond. Instead, many expressed their activism through the organizations that represented them and through their community publications. In the United States, the main organization was the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). Its organ was the Pacific Citizen, the best-known Nisei publication. In Canada, the Nikkei found expression in the following groups (in order of the date of formation): the Japanese Canadian Citizens League (JCCL); the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group (NMEG); the Japanese Canadian Citizens Council (JCCC); and the Japanese Canadian Citizens for Democracy (JCCD). The New Canadian, initially Vancouver-based and later Winnipeg-based, voiced the opinions of the JCCL while the Toronto-based Nisei Affairs circulated the largely Nisei views of the JCCD during and immediately after WWII.

American and Canadian Nikkei involvement in the campaigns to safeguard their rights was not restricted to advocacy within organizations. In the United States, Gordon Hirabayashi, Minoru Yasui, Mitsuye Endo, Ernest and Toki Wakayama, and Fred Korematsu took very public and very individual actions to oppose Washington’s orders. Had they not opted, at great personal risk to resist the incarceration of Japanese Americans, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) could never have sponsored test cases. Unlike its American counterparts, the Canadian litigation had no identifiable defendant. The case was a reference case; that is, a submission by the federal government to the Supreme Court of Canada asking for an opinion on a major legal issue. Nonetheless, the Nikkei were involved there too: the legal briefs and representations they made to government officials played an integral role in halting objectionable government actions. Collectively the dissenting US voices loudly proclaimed the need to respect the Bill of Rights. Canadian advocates had no such legal document to appeal to. Although the courts in the United States served as a check on the powers of elected representatives, under the British system that Canada inherited, Parliament reigned supreme. In the absence of constitutional protections, the principle of parliamentary supremacy meant that the elected representatives were responsible for passing and revoking legislation and the justices of the nation’s highest courts would not impinge upon the exclusive authority of the Parliament. For that reason, Canadian advocates appealed to the emerging discourse of human rights and depended on the court of public opinion more than on judicial channels.[1]

In many respects, the struggles of Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians to achieve voice, representation, and constitutional rights shared much in common; however, some of their approaches differed. Nikkei individuals and organizations cooperated with and received support from national organizations such as the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians (CCJC), an umbrella group formed in 1943 comprised of individuals and organizations from across the country, and the ACLU, a long-standing civil rights organization; members of both groups came from largely “respectable” white, middle-class background. In the US, the JACL worked closely with the ACLU. Eager to demonstrate its loyalty, the membership of the JACL complied with the removal orders and urged all Japanese Americans to follow suit. It became more militant by war’s end as its leadership came to view test cases as an effective tool in dismantling the internment legislation. The initial reluctance to support test cases placed the JACL in conflict with the ACLU.

Canada had no counterpart to the JACL until late 1947, when the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA) was created. While several Japanese associations existed in British Columbia, none had enough organizational clout or resources to claim national representation of Japanese Canadians and Japanese nationals, although the JCCD, the forerunner of the NJCCA attempted to perform such a function by the mid-1940s. Significantly, the CCJC welcomed Japanese Canadian members from its inception and later cooperated with the JCCD when it was formed; in the United States, Japanese Americans, deterred from directly participating in “white” groups, were encouraged instead to form their own organizations. The degree of solidarity expressed in the Canadian movement to protect the rights of Japanese Canadians would provide an important foundation for future human rights campaigns. The movement for justice for the Nikkei was not as significant a turning point or revelation in the United States as it was in Canada, likely due to the impact and precedent-setting nature of the deportation policy. Still, Nikkei activism in the 1940s provided important groundwork for inter-racial cooperation on issues of racial discrimination in the decades that followed.

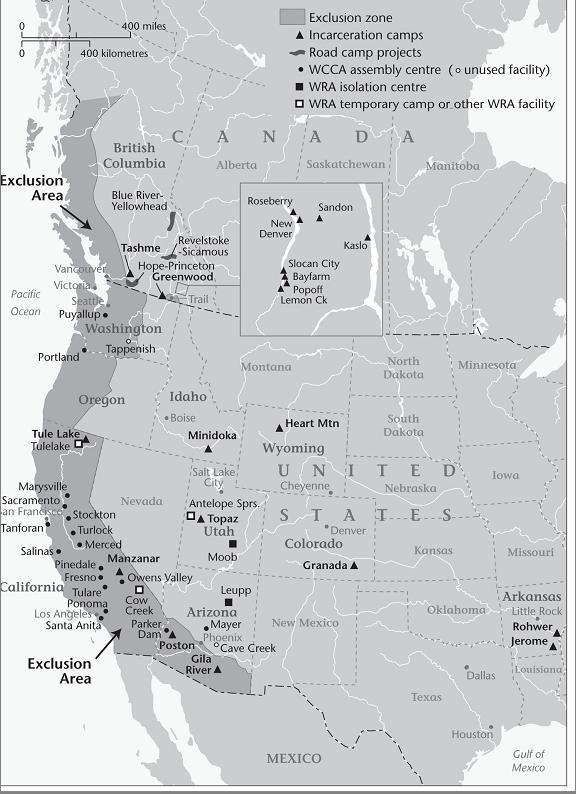

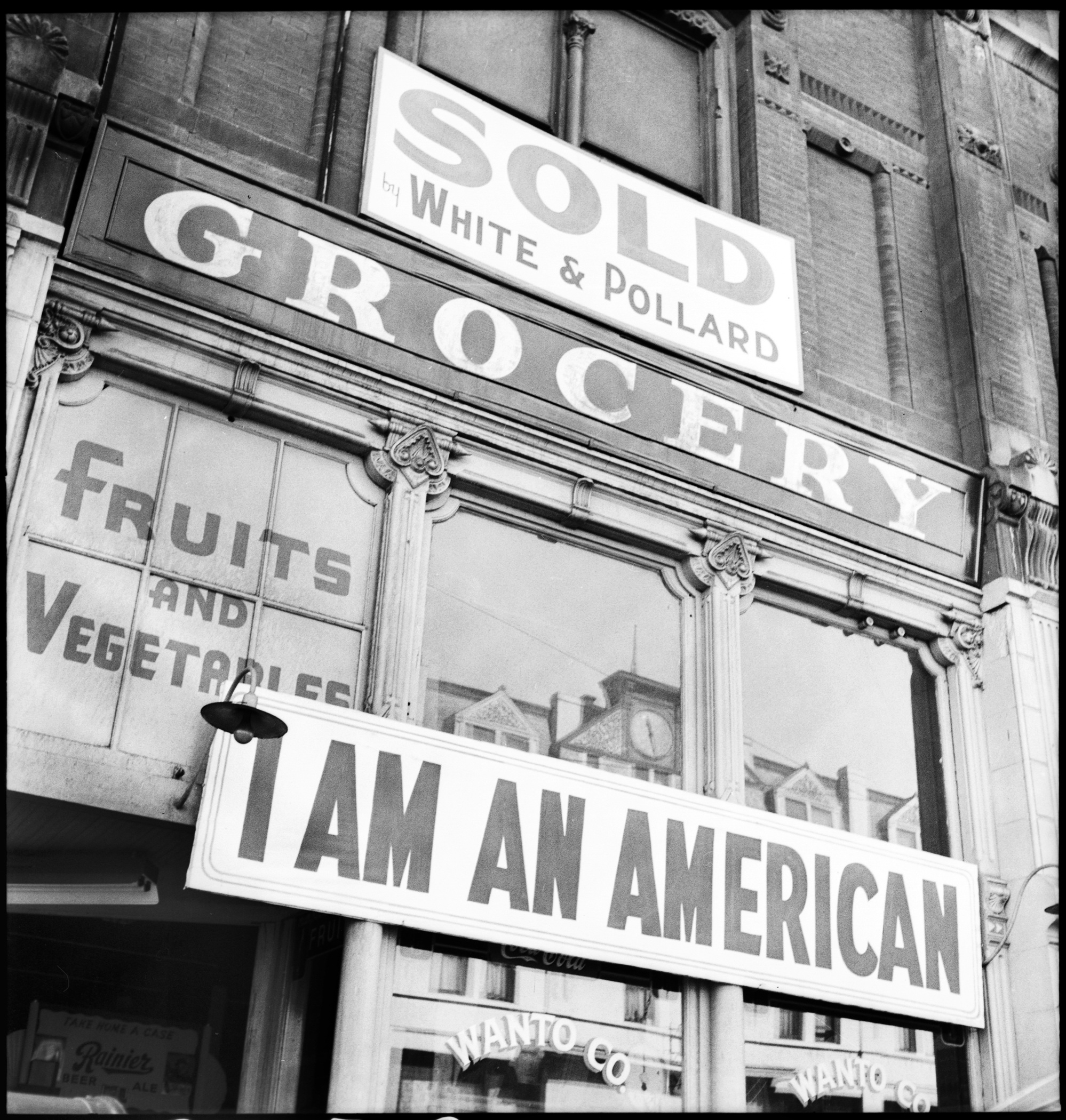

A basic accounting of the similarities and differences in the situation of American and Canadian Nikkei sets forth something like this: In North America in general, the Japanese were subjected to discriminatory treatment upon arrival, including the denial of citizenship rights in the US and franchise rights in Canada; they negotiated this impediment by clustering in “ethnic enclaves” primarily on the west coast and increasingly became objects of suspicion, fear, and envy over the course of the early twentieth century. Following the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, both countries “evacuated” Japanese aliens, Japanese nationals, and their North American–born children from their west coasts and “relocated” them to inland camps on the basis of “military necessity,” a politically expedient term legitimating an historic racist animus. This movement involved about 112,000 people in the US and nearly 22,000 in Canada.

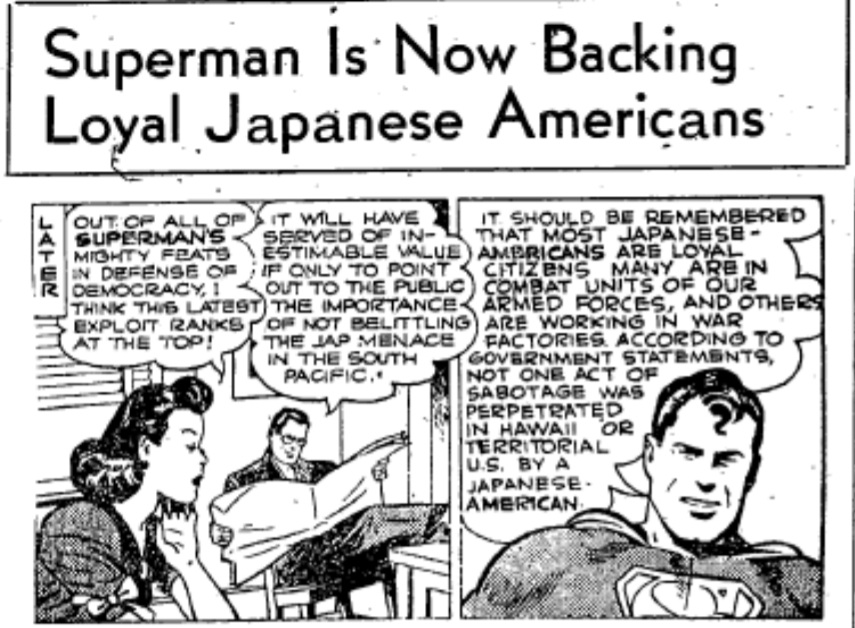

In the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor, both the US and Canada also developed policies that were used to defraud the Nikkei of their property and to encourage a more even “dispersal” of the population throughout the country. The policies diverged in the mid-1940s when the Canadian government expatriated Canadian citizens of Japanese ancestry and deported some Japanese aliens (those who signed repatriation forms requesting to be sent to Japan). The Americans also deported some, but only those who renounced American citizenship. Japanese Canadians were disfranchised by provincial and federal legislation; by virtue of the Bill of Rights, those Japanese Americans who had been born in the US were not. In addition, they were permitted to enlist and many did so proudly in the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. It is also worth noting that many Nisei who joined the armed forces did so while their families remained in the camps; still others resisted pressures to join, particularly after 20 January 1944 when the draft was reinstated for Japanese Americans.

Throughout much of the war, by contrast, their Canadian counterparts were prohibited from serving in the armed forces and thereby demonstrating their loyalty. Canadian government officials feared that in return for serving their country, Japanese Canadians might agitate for the franchise. It was only toward the end of the war that about 150 Nisei were permitted to work as translators for the Canadian military. Another important diffrence is that the US government allowed persons of Japanese ancestry to return to the Pacific coast in 1945 as a result of the Endo decision, whereas Japanese Canadians had to wait until 1949 when wartime government legislation finally lapsed.[2]

These and other differences aside, both countries experienced the development of significant organized dissent with respect to the above-noted policies. The JACL and Japanese Canadian groups initially focused on the conservative and accommodationist strategies of dispersal, assimilation, and patriotism. These responses reveal the degree of Nikkei faith in the main traditions of justice in each country: the British sense of justice and fair play in Canada and the Bill of Rights in the United States. While some Nikkei groups in both countries advocated cooperation with the removal and internment, not all Nikkei chose to regard the relocation as an “acid test” of Canadian and American democracy and of loyalty to their respective countries. Some directly engaged and clashed with government officials, while some American Nisei refused the draft and renounced their citizenship.

Nikkei in Canada and the US offered varying forms of resistance to relocation to the interior camps, despite pressures from within and without the Nikkei community to conform to government policies. Angered by their general treatment and by the specific proposal delivered in March of 1942 to separate families and send many Nisei males to work camps throughout Canada, Nisei in Vancouver created the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group. The NMEG formation was the first numerically significant resistance to removal. Its leadership was comprised of JCCC members who were expelled from the organization for open disobedience on the issue of family separation. In a 15 April 1942 letter to a government official, the NMEG firmly stated its scorn for the plan to break up family units:

When we say “NO” at this point, we request you to remember that we are

British subjects by birth, that we are no less loyal to Canada than any other

Canadian, that we have done nothing to deserve the break-up of our families,

that we are law-abiding Canadian citizens, and that we are willing to accept

suspension of our civil rights – rights to retain our homes and businesses, boats,

cars, radios and cameras. Incidentally, we are entitled as native sons to all civil

rights of an ordinary Canadian within the limitations of Canada’s war effort.[3]

The NMEG also pointed out the contradiction between the teachings of Canadian religious institutions – that family unity be regarded as a “God-given human right” – and a policy that would take away the freedom to live with their families. No such policy was enacted in the US, noted NMEG activists. Yet, even as the NMEG criticized this aspect of removal policy, it lauded the faith of its members in British fair play and justice. Some who were angry with the policy disobeyed the road camp orders and went ‘underground’, others interned themselves voluntarily in an immigration shed in Vancouver which was met by a show of force from the military. Strikes also occurred in the road camps. By July the NMEG’s protests achieved a degree of success when the federal government agreed to let married men return to their families, leaving several thousand single men in the work camps.[4]

Japanese American groups in the incarceration camps also organized resistance to the removal. The example of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, in particular, calls into question the stereotype of the Japanese American as victim of wartime oppression, responding only with patriotism and resignation. On 1 March 1944, 400 Nisei at the Heart Mountain camp voted to resist the draft until their constitutional rights were restored. By 26 June, 63 men from Heart Mountain were convicted for refusing induction. They were sentenced to three years in prison (267 from all ten camps were eventually convicted for draft resistance). Tule Lake was also a centre of resistance, mainly by the Kibei, a group of young Nikkei who had been born in the US and educated in Japan. They saw renunciation of their citizenship as the best means by which to resist. Nearly one-third of its residents applied for “repatriation” to Japan after the war, 65% of whom were American-born. At the Manzanar Camp, a camp-wide riot broke out on 6 December 1942, largely at the instigation of anti-JACL-War Relocation Authority “agitators” and joined by the majority of the camp population, many of whom were Kibei malcontents. After the military police were called in, two young males were killed and many others were treated for gunshot wounds.[5]

In Canada, the eastward resettlement resulted in the formation of other Nisei-based groups, most notably the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy. The close cooperation between the Japanese Canadian community in Toronto and the white, middle-class, politically active liberal members of the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians evolved in the early years of the Second World War. In 1944, the increasing politicization required to launch a serious campaign for Nikkei rights resulted in the official formation of the JCCD, which would ultimately become the leading Japanese Canadian organization at the time. Its purpose was five-fold: to publicize the Japanese Canadian question, to coordinate the activities of other Nisei organizations, to report on the educational and vocational trends of the Nisei, to provide for the social needs of the Nisei, and to promote the work of the CCJC. However, it did not speak for all Japanese Canadians. Groups in the province of Manitoba rejected the JCCD as they viewed it as not a truly national organization, and Japanese Canadians in Quebec rejected outright the notion of an organization. Additionally, generational cleavage existed between the Nisei and Issei, between the generation angered at what was happening to them and the generation of shigata-ga-nai, nothing can be done about it. Nonetheless, the views of the JCCD were the ones to be promulgated. Soon, Nisei Affairs began to print JCCD materials; in fact, though Nisei Affairs billed itself as a “Journal of Opinion,” viewpoints that deviated from the JCCD party line found no place in its pages.

Whereas the Japanese Canadian community fractured over maintenance of family unity and resistance to the federal government’s separation plan (but not significantly over internment itself), the Japanese American Citizens League instantly split Issei and Nisei in the United States. The JACL was for citizens only. It was also, as Roger Daniels states, a “hypernational” organization that rejected cultural ties to Japan, an approach that alienated Issei leaders. The JACL was marked less by power struggles and confusion over leadership among the Nisei generation than were its Nisei-run counterparts in Canada. Thus, it was able to become a strong organization that could address the needs of its constituents immediately following Pearl Harbor. The eagerness with which the JACL demonstrated Japanese American patriotism and loyalty to the US in early 1942 made it difficult to launch an effective effort to oppose removal.[6] Indeed, although the ACLU and the JACL cooperated closely in the later years of the war on test cases and other matters, such was not the case in early 1942. The JACL was “unalterably opposed” to test cases challenging the incarceration orders. The test cases represented the cornerstone of ACLU advocacy for Japanese Americans. By mid-1942, some Nisei, including some JACL leaders, had become frustrated with the non-confrontational stance of the JACL. In the Pacific Citizen Saburo Kido, JACL president, commented that the “Native Sons have raised $1000 and the Native Daughters, a similar amount, to launch the movements to deprive us and our children of our citizenship rights. Are we going to do anything to defend what we have so that we may resume our role as citizens once the war is over?”[7]

Kido’s plea to the Citizen’s readers certainly did not amount to full support for the ACLU program, but it set in motion closer cooperation between the ACLU and the JACL on the issue of test cases.

Although the Nisei were strongly pressured to join the JACL, many resisted, refusing to subscribe to its initial American boosterism. In a letter to the Tolan Committee (also known as the House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration), the Los Angeles United Citizens Federation, a very small Nikkei group, officially criticized the relocation program and the JACL leadership. For example, a YMCA employee from San Francisco named Lincoln Seiichi Kanai, while appearing before the committee objected to the indiscriminate identification of American citizens of Japanese ancestry with alien enemies.

Another member, James Omura, a florist and part-time editor of a liberal Nisei magazine, made an impassioned plea to the Tolan Committee expressing disdain for the JACL and strong opposition to removal. But such examples of resistance in the early days of the incarceration were few; military authorities had issued a warning that Japanese Americans would be removed by force if they called for or engaged in resistance. James Omura became editor of a newspaper called the Denver Rocky Shimpo. In 1944, after publishing statements issued by the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee and supporting the committee in his editorials, he was indicted for conspiracy to violate the Selective Service Act and for counselling resistance to the draft. The statements had declared that Fair Play Committee members would not cooperate with the draft unless their citizenship rights were restored. The cost of the trial bankrupted Omura’s newspaper.[8]

Although Nikkei protest movements began slowly, by the mid-1940s Japanese Canadian and Japanese American advocacy groups moved with greater urgency. There were some important motivating factors: in the U.S., the test cases launched by ACLU affiliates in Northern and Southern California were making their way through the legal system; in Canada, the federal government was passing increasingly draconian measures against persons of Japanese ancestry. When the Canadian government approved Bill 135 in 1944, in which the federal disfranchisement of British Columbia’s Nikkei was extended to all those who had left the province to live elsewhere in Canada, the JCCD, in cooperation with the CCJC, saw an opportunity to demonstrate its newfound political ambitions. Anti-Nisei politicians had long alleged that the Nikkei were uninterested in exercising the franchise, and furthermore that they could not undertake the level of Canadianism that correlated with the appreciation of the right to vote. JCCD representatives traveled to Ottawa, the capital of Canada and seat of the federal government, to opposed the bill. Their brief noted that the “proposed amendment is contrary to British justice, and contrary to the expressed war aims of the United Nations.”[9] It is interesting to note that at this point in the mid-1940s Japanese Canadians sought to bolster their desire for equality by appealing to the Atlantic Charter. “British liberties” could go only so far to protect the rights of minorities. The federal government’s Japanese Canadian policies demonstrated that it did not fully accept the emerging international objective of promoting fundamental human rights. With its appeal to citizenship rights and the Atlantic Charter, the JCCD’s brief on the disfranchisement clause was an important contribution to rights discourse in Canada. It would become a major component of Canadian resistance to the deportation policy.

In 1945, when Japanese Canadians in British Columbia were forced to choose between resettlement throughout Canada, or “repatriation” to Japan, the JCCD joined with the CCJC in their delegations to federal government officials and the efforts to overturn the deportation policy. The New Canadian exhorted all Nisei to join in the fight, including the Nisei Fellowship in Montreal, the Sophy-Ed Club in Hamilton, the Manisei group in Winnipeg, the Youth Central in Lethbridge. In the meantime, other Nisei-based groups began working towards the same goals, cooperating closely with the JCCD and the CCJC. The leadership of the Lemon Creek Housing Centre in the BC Interior alerted the CCJC to the duress involved in the decisions for repatriation on the part of some of Nikkei. The JCCD and the Slocan Valley Nisei Organization, a group comprised of the Japanese committees of the five incarceration camps in the interior of BC (New Denver, Bay Farm, Lemon Creek, Slocan City, and Popoff), also kept in contact regarding a plan of action to fight the repatriation orders. They actively petitioned Prime Minister King and other senior members of government. Earlier in 1945, this group had petitioned King to allow parents to remain in Canada, on the grounds that they “appreciated the democratic way of life for their children and have urged them to assume the full obligations of citizenship.”[10]

Government officials remained unmoved by the appeals and delegations. In early December 1945, Ottawa announced that the first nine hundred would be deported to Japan in early January. JCCD and CCJC members decided to employ litigation to overturn the deportation program. Kinzie Tanaka, Kunio Hidaka, and other members of a CCJC special committee planned the legal strategy. The JCCD appointed a Citizenship Defence Committee (CDC) to raise funds from Japanese Canadians across Canada, eventually collecting over $10,000 to finance the Supreme Court challenge and, later, the appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain. The CDC, comprised of Issei and Nisei members, served as a CCJC affiliate member. On its own, the JCCD, by way of the CDC, collected $1,486; by 23 January 1946, it had given $1,000 to the CCJC for legal expenses.[11]

The JACL’s stance on non-participation in test cases was effectively abandoned when the JACL submitted an amicus brief in the Hirabayashi case. In 1942 Gordon Hirabayashi defied a military order that required “all persons of Japanese ancestry” to register for evacuation to the state fairgrounds at Puyallup, south of Seattle. This individual act of resistance was fostered by his Quaker roots and his belief in due process and civil liberties. The Seattle branch of the ACLU initially championed the case; upon reaching the US Supreme Court it was joined by the national ACLU. The JACL brief, drafted by Morris E. Opler, a community analyst at the Manzanar Relocation Center in California, levelled a charge of racial discrimination at the government’s policy. Opler sought to demonstrate that Japanese Americans were no different from any other immigrant group in either their attempts to assimilate and seek acceptance in American society or their retention of old-world conventions such as language, religion, and cuisine. The JACL brief also questioned the motives behind the military orders. Opler cited Lieutenant General DeWitt’s statements, such as “a Jap’s a Jap”, and his assertions that American citizenship did not guarantee loyalty, as evidence that racism, not military necessity, was the real issue in the case. Some Japanese Americans in the assembly centres supported Hirabayashi. For example, residents of the Topaz Relocation Center contributed $1,312 to support this and other test cases.[12]

Nisei resistance and discontent was also evident in the pages of the Nisei press. The Pacific Citizen observed wryly that, due to its past and present treatment of the Nikkei, “Beautiful San Francisco” had forfeited its right to become the home of the United Nations. During the UN conference meetings in that city, it reported, “Certain Californians took to burning down the homes of evacuees, to shooting into their homes, and some of these incidents took place but a few miles from the spot in which delegates from the entire world were planning a prejudice-free world.” The Canadian Nisei Affairs borrowed from the Double-V campaign of the African American press. The paper remarked that because young Nisei were attempting to volunteer for the Canadian army, Canadians on the home front should begin to address racial prejudice.

An editorial in another issue condemned deportation as being contrary to the values of Canadian citizenship. The bold title of a 3 November 1945 New Canadian column – “Deportations a Violation of Human Rights” – made the point crystal clear.[13]

By the mid-1940s, the political organization of the Japanese Canadian community was undergoing a significant change. The clearest manifestation of this was the movement to create a larger national political association to replace local groups. Although the JCCD was gradually becoming recognized by other Nikkei organizations and government officials it endeavoured to form a “truly national” organization of Japanese Canadians. Even its outlook became more international, as evidenced by the fact that it sent a twenty-five dollar donation to a Japanese American organization in support of its activities.[14] As a result of continual lobbying throughout the 1940s, Japanese associations across Canada realized that a unified effort was necessary to win equal rights. For this, the JACL was consulted, and its president, Mike Masaoka, was partially influential in guiding the federated structure and the objectives of the new group. In an emotional speech in Toronto, Masaoka said, “Many of us Nisei in the States, who took on the thankless task of leading our people into the camps and out again back into civilian life, did so only because we knew that someone had to do it. Some of us were beaten up by our own people, but that didn’t stop us from fighting for our rights as American citizens!”[15] Thus, in September 1947, with the end of the expatriation issue, the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy dissolved. It became part of the Toronto chapter of the Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (JCCA), but not before altering its rules to allow the Issei to join, indicating the degree to which some Nisei were willing to mend the intergenerational strife that had plagued the community for decades. Other Canadian groups followed suit, unifying under the National JCCA (NJCCA), which was Toronto-based and comprised mainly of former members of the JCCD.[16]

Both the JACL and the NJCCA, in cooperation with the ACLU and the CCJC, respectively, sought financial redress for the sale and confiscation of property. In both cases, the JACL and the NJCCA assumed responsibility for coordinating the claims procedure. In this final chapter of the relocation process, the NJCCA benefited from the prior experience of the JACL. Delegates at the National Conference on Japanese Americans, held in New York on 8 November 1945, formally discussed the idea of restitution for property loss and sent a letter to President Harry Truman supporting the indemnity claims of Japanese Americans. The ACLU offered to coordinate, through its coastal and national offices, the collection of claims in order to build a case for action by Congress. The JACL assisted Japanese Americans in filling out the forms. In 1948, Congress passed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, which gave the Nikkei the right to claim from the government “damage to or loss of real or personal property” not compensated by insurance that had occurred “as a reasonable and natural consequence of the evacuation or exclusion.”[17] Claims pertaining to emotional losses, such as the psychological impact of relocation, or even physical injury or death, were not addressed, nor were the losses of earnings or profits. Under the act, 26,568 claims totalling US$148 million were filed; the total amount disbursed by the government was approximately US$37 million. Adding to the problem of claims assessment was the fact that, by 1948, the IRS had destroyed most of the 1939-42 income tax returns of the affected Japanese Americans. Acting on this information, the JACL attempted in 1954 to widen the scope of the act, but to no avail, as the necessary documentation no longer existed.[18]

By 1946, the CCJC and the JCCD had turned their attention to securing compensation for Japanese Canadian property losses. The JCCD modified a claims form used by the ACLU and the JACL and local chapters distributed it throughout Canada in order to gather details on property losses. The claims procedure involved the Canada-wide cooperation of local NJCCA and CCJC chapters. Later, the CCJC and the NJCCA would use this evidence in approaching the government to establish a claims commission. After CCJC and JCCD delegates met with the prime minister on 27 May 1947, Justice Bird was appointed under the Public Inquiries Act to head a royal commission to investigate property losses, but only those losses arising from negligence or lack of care by the property custodian or his staff. Lawyer Andrew Brewin lobbied Ottawa on behalf of the CCJC-NJCCA coalition to widen the terms of reference. The government agreed but only in case of losses incurred through the sale of property by the custodian at less than its fair market value, or through the loss, destruction, or theft of personal property vested in the custodian (but not while in the care of someone else). In the end, over eleven hundred claims were handled by the CCJC-NJCCA counsel, and by 1950, Bird’s final report was submitted to Cabinet. The government stated that $1,222,829 would be paid in awards. In all, the overall recovery on the claims was 56 percent of the gross value claimed. A group known as the Toronto Claimants Committee was especially vocal in its disapproval of the handling of the case, arguing, among other issues, that the CCJC acquiesced too easily to government guidelines.[19]

The CCJC-NJCCA coalition continued to fight for more compensation, urging the government to pay interest on the awards recently granted and in September 1950, the NJCCA sought further redress by submitting a brief to the government that criticized the Bird Commission’s narrow terms of inquiry. It proposed compensation for general losses, interest on all awards, the creation of an agency to address losses on forced sales, and percentage settlements on various other losses. Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent put closure to the NJCCA appeals when he informed the CCJC that “in carrying out the recommendations of Mr. Justice Bird we feel we have discharged our obligation to both the Japanese Canadians and to the general public.”[20] The NJCCA-CCJC partnership ended with the disbanding of the CCJC in mid-1951. An important legacy of this cooperation, however, was the development of modest ties between the Japanese Canadian community and two other minority rights organizations – namely those representing Jews and blacks. Similar forms of cooperation between groups representing minorities were also evident in the United States.

The relocation and expatriation issues enabled minority groups in Canada and the US to recognize their common problems. As the war neared its end, marked by Allied victories, public opposition to such racially based policies as relocation and expatriation became more pronounced. As a result, dissent, including dissent from minority representative organizations, became more acceptable. Indeed, shortly before the NJCCA was formed, Kinzie Tanaka, as editor of Nisei Affairs, was among the first to exhort the Japanese Canadian community to work towards the “common good” and to stress that “we shall not attain our ends until we have fought unselfishly for the other’s struggle for some basic human right.” Calls for Japanese Canadians to work for the rights of Jews and African Canadians were repeated in its pages. Writing in Nisei Affairs under the pen name Sue Sada, Muriel Kitagawa critiqued the government policy of continuing post-war restrictions on Japanese Canadians, titling her piece “Today the Japanese – Tomorrow?” Not surprisingly, the national JCCA support the demand for a Canadian bill of rights and fair employment practices legislation. A brief submitted to Parliament by the Committee for a Bill of Rights even included a clause disallowing the exile of Canadian citizens, clearly an acknowledgment of the expatriation struggles of the Japanese Canadian community. With the campaign for Fair Employment Practices legislation, in Ontario in particular, ethnic communities realized the value of coalition building.[21]

The JACL amended its membership policy in late 1944 to permit all Americans to enroll as members, regardless of race. This new proposal reflected the broadened scope of JACL activities in recognizing the wider problems of minority groups. It also illustrated the desire on the part of activist Nisei to break down the barriers imposed on and by other minority groups. The JACL made further advances in interracial cooperation with the founding of an Anti-discrimination Committee (JACL-ADC), incorporated in 1946 as its legislative activist agency. It was created with the following goals: to push for legislation that, while of interest to Nikkei groups, would “probably be initiated and receive its primary support from other organizations”; to advance “general civil rights and social legislation which … may be expected to receive support from organizations interested in ‘equal rights and equal opportunities for all’”; and to oppose legislation that the JACL-ADC deemed “inimical and detrimental to the welfare of this country or its people.”[22] The JACL also established a Legal Defense Fund in late 1946. Its purpose, not surprisingly, was to defray legal and court costs in litigation involving civil and property rights of racial minority groups that the JACL would initiate or participate in as a “friend of the court.” To that end, the Legal Defense Fund contemplated submission of briefs in cases involving restrictive covenants against African Americans and members of other minority groups. In the immediate post-war period, JACL and NAACP attorneys united to fight the California Alien Land Act and to challenge racially restrictive covenants, at times as part of a larger multigroup struggle.[23]

Conclusion

Some forty years after the Second World War ended Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians and their organizations were at the forefront of another significant redress campaign. In 1988, both Canada and the United States officially endorsed redress, their actions forty-three days apart. On 10 August (in an election year), Republican president Ronald Reagan formally announced that under the Civil Liberties Act each survivor of the incarceration would receive an apology and US$20,000 tax-free as compensation. On 22 September (also in an election year), the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney unveiled a similar policy. It agreed to pay C$21,000 to each survivor. Furthermore, it created what is now known as the Canadian Race Relations Foundation to serve as a memorial for the Japanese Canadian community and in an investigative capacity for historic injustice. Nikkei activists were at the forefront of both campaigns for redress.

Japanese American groups also demonstrated their organizational strength in the coram nobis cases of 1983, which served as an important parallel to the redress campaign. A writ of error coram nobis (the error before us) is a legal device that allows a person convicted of a crime to challenge the conviction on certain grounds after having served the sentence. This litigation sprang from a discovery made by Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, a clerical worker turned researcher, and Peter Irons, a university professor, civil rights lawyer, and political activist. When the two learned that War Department and Justice Department officials had knowingly altered, suppressed, and destroyed evidence in the wartime Japanese American cases, Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Minoru Yasui filed coram nobis petitions in early 1983 that sought to set aside their convictions. Although the coram nobis litigation discredited the factual basis of the 1943 cases and the convictions were vacated, the Supreme Court rulings still stand, specifically that of Korematsu, with its expansive interpretation of the wartime powers of government. None of the coram nobis cases reached the Supreme Court for final verdict, as the Reagan administration’s Department of Justice refused to appeal the reversals of Korematsu and Hirabayashi; Minoru Yasui’s death in November 1986 rendered his case moot.[24]

Indeed, the principles that Fred Korematsu, Min Yasui, and Gordon Hirabayashi followed during the war are now being taken up by their children in an amicus brief in support of a class action lawsuit accusing federal officials of racial profiling and wrongful detainment. The class action lawsuit (Turkmen v. Ashcroft) was filed by Ibrahim Turkmen and Akhil Sachedva, who were among hundreds of immigrants detained in the months following the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. For Eric Muller, a noted legal historian who filed the amicus brief, and for Karen Korematsu-Haigh, Holly Yasui, and Jay Hirabayashi, the similarities between the plight of the Issei in the aftermath of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the struggle of Arab and Muslim immigrants after September 11 are striking. The brief holds that the Issei, much like Arab and Muslim immigrants in today’s political climate, were singled out by the government because of race and that the federal trial judge who dismissed the case (Turkmen v. Ashcroft) resorted to the same legal theory that had justified the incarceration of Japanese aliens in the Second World War. The judge concluded that it was acceptable to use race and religion to distinguish foreign nationals and subject them to detainment on the ground that the 9/11 perpetrators were Arab nationals who belonged to an Islamic fundamentalist group. The Turkmen decision justifies racial profiling in circumstances where the government can claim urgent need in response to a perceived “enemy.”[25]

Memories of the incarceration were revived with the campaign to save Joy Kogawa’s childhood home from demolition, slated for 1 May 2006. Located in Vancouver’s Marpole neighbourhood, the house figured prominently in Obasan, Kogawa’s evocative and acclaimed novel of the incarceration and Canada’s treatment of its citizens of Japanese ancestry. A fundraising drive initiated through the Land Conservancy of British Columbia required $1.25 million to buy the house, renovate it, and create a writer-in-residence centre, as well as a place for schoolchildren to learn about the Japanese Canadian experience. Although the campaign progressed slowly, it eventually achieved its goal when it received an anonymous donation of $500,000. Although the house was saved, money is still being raised to assure its place as a physical reminder of injustice and as a haven where writers facing persecution in their homelands may challenge it.[26]

Persons of Japanese ancestry were active in their own defence and participated in the articulation of human rights as an important concept throughout the 1940s. Despite community pressures to abide by government policy, Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians initiated many of the early protests challenging the discriminatory policies directed at them. Indeed, little distinguished the human rights discourse of the JACL from that of Canadian human rights advocates, whether Japanese

or non-Japanese. The decision of Nisei-based organizations to cooperate fully with other Canadian advocacy groups, particularly the CCJC, and the evidence that the Nikkei were at the forefront of advocacy is emblematic of the nature of the fledgling human rights movement in post-war Canada. Long before multiculturalism became a state-sanctioned policy, certain Japanese Canadians were among the first to champion the full participation of racial and ethnic minorities in Canadian democracy. Examination of the advocacy materials drafted by Japanese organizations in Canada and the United States reveals a remarkably similar series of aims related to the respect for human rights.

This study has demonstrated that when collective voices are raised in protest, they can make a difference. In the words of a Canadian activist,

Here is one clear-cut example of how individual citizens, by banding

together, managed to change the course of events in a very significant way. They made democracy work because they cared enough about it to make it work. What they did can be repeated.[27]

Stephanie Bangarth is an assistant professor of History at King’s University College at The University of Western Ontario. E-mail: [email protected]

She wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted January 31, 2008.

Notes

[1]. Space does not permit a full discussion of this aspect of Nisei resistance. For further information see, for example, Stephanie Bangarth, Voices Raised in Protest: Defending North American Citizens of Japanese Ancestry, 1942-1949 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008), chap. 4; Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983); and Ross Lambertson, Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930-1960 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), chap. 3.

[2]. Representative works on the wartime treatment of the Nikkei include: Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was: A History of Japanese Canadians Rev. ed. (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991); Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps USA: Japanese Americans and World War II (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1981); Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003); Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2001); Patricia E. Roy, J.L. Granatstein, Masako Iino, and Hiroko Takamura, eds., Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during the Second World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990); Robert Shaffer, “Cracks in the Consensus: Defending the Rights of Japanese Americans during World War II,” Radical History Review 72 (1998): 84-120; Ann Gomer Sunahara, The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War (Toronto: James Lorimer, 1981).

[3]. NMEG to Austin Taylor, British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC), 15 April 1942, Library and Archives Canada [LAC], RG 36/27, vol. 3, series 27, file 66.

[4]. Ibid. Roy Miki devotes an entire chapter to the NMEG struggle in Redress: Inside the Japanese Canadian Call for Justice (Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 2004), chap. 3.

[5]. For full details regarding the Heart Mountain resisters, see Daniels, Concentration Camps: North America (Florida: Krieger Publishing Company, 1993), 118-29. For a description of the Tule Lake resistance, see Dorothy S. Thomas and Richard S. Nishimoto, The Spoilage (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1946), and Gary Y. Okihiro, “Tule Lake under Martial Law: A Study in Japanese Resistance,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 5, 3 (Fall 1977): 71-85. For differing accounts of the Manzanar riot, see Thomas and Nishimoto, The Spoilage, 49-52; Allan Bosworth, America’s Concentration Camps (New York: W.W. Norton Press, 1967), 157-62; Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis, The Great Betrayal (New York: Macmillan Press, 1969), 263-66; and Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, rev. ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 121-33.

[6]. Daniels, Concentration Camps: North America, 24-25.

[7]. Saburo Kido, “US Nisei Must Raise Funds to Fight Threats to Civil Liberties,” Pacific Citizen 15, 6 (9 July 1942).

[8]. United States Congress, House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, Hearings before the Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, 77th Congress, 2nd Sess. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1942), p. 29, 11266-67. With the support of the ACLU, Lincoln Seiichi Kanai filed a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds that imprisonment would deny him due process and equal protection of the law, and that compliance with the evacuation orders would be a negation of his citizenship status. Eventually charged with violation of military orders, he was sentenced to six months in prison. The federal district judge in the case described him as a “full blooded Japanese.” The ACLU did not appeal. “Memorandum on the Court Cases Contesting the Evacuation of American Citizens of Japanese Ancestry,” January 1943, Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University, MC 005, Roger N. Baldwin Papers, box 18, folder 9; Besig to Baldwin, 1 August 1942, Princeton University, Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library [Mudd Library], ACLU Papers, vol. 2397. James Omura’s testimony can be found in United States Congress, Hearings, 11229-32. See also Paul Spickard, “The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese American Citizens League, 1941-1942,” Pacific Historical Review 52, 2 (May 1983): 162-64.

[9]. JCCD Brief in the Matter of the War Services Elector’s Bill (#135 of 1944) Section 5 regarding Certain Amendment to Section 14 ss. 2 of the Dominion Elections Act, 1938 and in the Matter of the Proposed Disfranchisement of British Subjects and Canadian Citizens in Canada [JCCD Brief], 24 June 1944, 2, LAC, MG 28 V7, vol. 1, file 23.

[10]. “We Must Fight Deportation,” New Canadian, 10 November 1945; Japanese of Lemon Creek to Mrs. Hugh MacMillan, 29 October 1945, LAC, MG 28 V7, vol. 1, file 6; Slocan Valley Nisei Organization to Margaret Foster, 16 March 1946, LAC, MG 30 C69, Margaret Foster Papers; CCJC News Bulletin 4, 15 March 1945, CCJC-MAC, folder 10.

[11]. JCCD, Minutes, 21 December 1945, 31 January 1946, LAC, MG 28 V7, vol. 1, file 7; Nisei Affairs 1, 6 (19 January 1946); Peter Nunoda, “A Community in Transition and Conflict: The Japanese Canadians, 1935-1951.” PhD diss., (University of Manitoba, 1991), 249-50; Fowke, They Made Democracy Work, 19-20, LAC, MG 28, series 6, vol. 2, file 13.

[12]. Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943), Brief, Japanese American Citizens League, amicus curiae; “JACL Brief in Evacuation Raised Cases Opposes Race Issue by Government Attorney,” Pacific Citizen 16, 19 (13 May 1943); Irons, Justice at War, 192-93; ACLU national board, Minutes, 18 December 1944, Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University, ACLU Papers, vol. 2584.

[13]. “World Capital,” Pacific Citizen 22, 2 (12 January 1946); Editorial, Nisei Affairs 1, 2 (28 August 1945), and editorial, 1, 4 (31 October 1945); “Deportations a Violation of Human Rights,” New Canadian, 3 November 1945.

[14]. JCCD executive, Minutes, 26 February 1946, LAC, MG 28 V7, microfilm reel C12818, file 1-7.

[15]. Quoted in Kitagawa, This is My Own, 260.

[16]. JCCD Annual Secretariat Report, 1 November 1946, LAC, MG 28 V7, microfilm reel C12818, file 1-8. As of 2 April, the Issei were allowed to join the JCCD; as of the date of this report, 150 had done so.

[17]. Toru Matsumoto, Committee on Resettlement of Japanese Americans, “To the Delegates,” 7 December 1945, Mudd Library, Princeton University, ACLU Papers, vol. 2664; Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, 50 U.S.C. App. s. 1981 et seq., s. 1981(a).

[18]. United States, Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, rev. ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 118-19; Roger Daniels, Prisoners without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II (1993; rev. ed., New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 88-90.

[19]. “Statement to Claimants Re: Origin, Nature and Work of the Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians, April 1950,” 3-15, McMaster University Archives, CCJC Papers, folder 13; F.A. Brewin, “A Review of Property Claims,” New Canadian, 20 October 1948, LAC, RG 36/27, vol. 34, file 2202. For more on the Toronto Claims Committee dissent, see Nunoda, “A Community in Transition and Conflict,” chap. 9.

[20]. G. Tanaka to Louis St. Laurent, 23 September 1950, LAC, MG 28 V7, microfilm reel C12818; St. Laurent quoted in Sunahara, The Politics of Racism, 159-60.

[21]. George Tanaka, “For the Protection of Human Rights,” 26 January 1950, LAC, MG 28 V7, National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association Papers, microfilm reel C12830 Nisei Affairs 2, 1 ( January 1947); Nisei Affairs 2, 3 (April 1947); Nisei Affairs 2, 4 ( June 1947); Kitagawa, This Is My Own, 236-41; Ross Lambertson, Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930-1960 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), chaps. 5 and 8.

[22]. Japanese American Citizens League, Anti-discrimination Committee, “National Legislative Program-1949,” Princeton University, Mudd Library, MC 005, Roger N. Baldwin Papers, box 1056.

[23]. For more on this discussion, see Greg Robinson and Toni Robinson, “Korematsu and Beyond: Japanese Americans and the Origins of Strict Scrutiny,” Law and Contemporary Problems 68, 29 (September 2005): 29-49.

[24]. Ibid.

[25]. David Cole, “Manzanar Redux?” Los Angeles Times, 16 June 2006; “Amicus Brief Ties Internment to 9/11 Cases,” Rafu Shimpo Online, 9 April 2007, www.rafu.com/amicus.html; Lydia Lin, “Following in their fathers’ footsteps,” Pacific Citizen, 20 April 2007.

[26]. Columnist Rod Mickleburgh covered the Save Joy Kogawa House campaign in the Toronto Globe and Mail (“Donations needed to save a landmark,” 21 April 2007, and “Firm helps buy B.C. landmark,” 1 June), as did Camille Bains in “Kogawa’s childhood home to be saved,” 29 April 2007.

[27]. Edith Fowke, They Made Democracy Work: The Story of the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians (Toronto: Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians, 1951).