Simon Nantais

Abstract

A Canadian diplomatic mission led by Rodolphe Lemieux in November 1907 shares an anniversary with the much-maligned Japanese immigration controls, introduced on 20 November 2007. The themes underlying the Lemieux mission – racial profiling, xenophobia, discrimination in immigration, and claims of unassimilability in the host country – resonate deeply with the current political climate in Japan. The anniversary of Lemieux’s arrival in Japan 100 years ago serves to remind us how little attitudes have changed in regards to immigration and racialization.

The furor over Japan’s new discriminatory immigration procedures was palpable. [1] From 20 November 2007, all visitors to Japan face rigorous screening tests. “Visitors to Japan” is a rather dishonest term, one that underlines the Japanese government’s ambiguity, if not outright hostility, to immigrants. In the “Visitors to Japan” queue, nearly everyone who does not possess Japanese citizenship undergoes the new high-tech (retinal scans), low-tech (finger-printing), and oral questioning immigration control procedures. This means that all non-Japanese who possess spousal visas, cultural visas, and even Japanese permanent resident status are treated like criminals as they return to the country that initially “permitted” them (thanks to the re-entry permit) to return in the first place. Ironically, the only non-Japanese citizens not to suffer this fate, other than diplomats and children under 16, are “special-status permanent residents,” a code for the large, mostly Korean, zainichi population. For 40 years, from 1952 to 1992, under the Alien Registration Law, the zainichi were forced to submit their fingerprints until a campaign of civil disobedience, with the active support of several provincial politicians, ended the discriminatory measures. The zainichi would never allow such a measure to be enforced on them again. The United States, under the US-VISIT program, is currently the only other country to enforce such strict port-of-entry procedures for visitors, including finger-printing and retinal scans, but even they exempt their permanent residents.

Justice Minister Hatoyama Kunio claims that these strict measures will keep Japan safe from acts of international terrorism. In a well-publicised gaffe, Hatoyama said “a friend of a friend of mine is a member of al-Qaeda” and that the suspected terrorist entered Japan with false passports and disguises. [2] Though the foolish remark was dismissed by Hatoyama’s own Ministry, it nonetheless demonstrated the rather shallow premise for invoking such draconian measures. Furthermore, by attempting to (falsely) demonstrate how easy it was for foreigners to enter Japan illegally, the comment squarely placed the blame for a future terrorist attack on Japanese soil on foreigners, rather than on faulty Japanese intelligence or lax immigration controls. [3] The governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) have refused to back down in the face of international criticism that the measures are a violation of human rights. Furthermore, as the measures treat every non-Japanese as a potential terrorist or criminal, it is clearly a case of racial profiling of the highest degree.

The mid-November 2007 implementation date marks a curious anniversary that Minister Hatoyama should note. On 7 September 1907, a mob of Canadian and American whites pillaged the Chinese and Japanese communities of Vancouver, British Columbia, a tragic event known as the “Vancouver Riot.” [4]

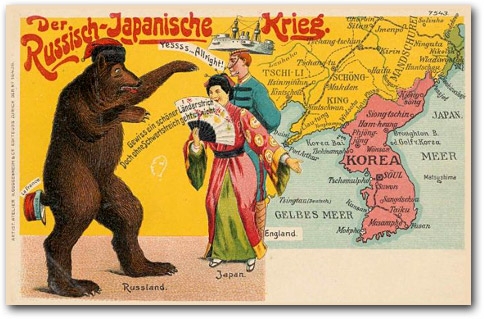

Subsequently, in November 1907, the Canadian Minister of Labour and Postmaster-General Rodolphe Lemieux led a small diplomatic delegation to the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo to request that the Japanese government severely curtail Japanese emigration to Canada. The Japanese had recently confirmed their status among the Great Powers with their military victory over Russia in 1904-1905 and their alliance with Great Britain. They were now livid that the Canadian government trampled over their treaty rights and that they were now discriminated against solely because of their race. With the successful conclusion of the “Lemieux Agreement” (also known as the “Gentlemen’s Agreement”) in early 1908, the proud Japanese were crestfallen to be lumped in the same category of restricted and undesirable immigrants as the Chinese and “Hindoos” (who were in fact Sikh Indians). This paper examines the Lemieux Mission and its political background, with emphasis on how the issue of race in Canadian society and politics dictated the pace of negotiations with the Japanese government. With the advent of Japan’s new discriminatory immigration procedures, the Lemieux Mission offers interesting lessons about the history of racial profiling and immigration. It is a case where the shoe (or the geta as the case may apply) is now on the other foot.

Background to the Lemieux Mission

During the first decade of the twentieth century, Canadian society witnessed a boom like no other it had experienced before. Tapping into this optimism, the Liberal Prime Minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier (1896-1911), famously promised that “the 20th century will belong to Canada.” The population grew exponentially as new immigrants from Europe claimed their 160-acre parcel of prime prairie farmland. Canadian business and industry, protected by a British Imperial tariff, enjoyed robust growth after a series of lean years in the late 19th century. Although most immigrants were generally welcome to Canada, skilled labourers, such as engineers, were particularly sought after.

Canadian attitudes to Asian immigrants, however, were generally hostile. While cheap Chinese labour was invaluable in constructing the trans-continental Canadian Pacific Railway that would link the Atlantic with the Pacific, they were no longer welcome to Canada after this project was completed in 1885. Successive Liberal and Conservative governments both imposed restrictions on Chinese immigrants, which, before the Lemieux Mission, culminated in the $500 “head tax” of 1903. For Chinese labourers, this was equivalent to two years’ salary and effectively barred their entry to Canada. Until 1907, Japanese migrants to Canada were relatively few, as most settled in Hawaii. Furthermore, as Iino Masako reminds us, the Meiji government did not encourage large-scale immigration to continental North America until 1905-06. [5] Nonetheless, at the time of the Vancouver Riot, nearly one-quarter of British Columbia’s population, the Canadian province bordering the Pacific, was of Asian descent.

Politicians of all political stripes in British Columbia never lost votes in calling for a “White Man’s Province” and several claimed active membership in anti-Asian groups, such as the “Asiatic Exclusion League.” These anti-Asian associations claimed that thousands of Japanese came from Hawaii and landed in the United States, only to flood across the “porous border” into B.C. At the turn of the century, the majority of B.C.’s white population was British-born or of British descent and they were strong pro-British imperialists. The B.C. provincial government routinely passed anti-Asian legislation, aimed at restricting their entry in the province or barring them from employment in certain sectors of industry. The federal government in Ottawa often had to declare such legislation unconstitutional, citing not its own displeasure with the province’s discriminatory legislation, but rather the need to retain British imperial unity. [6]

Great Britain’s diplomatic rapprochement with the Meiji government complicated matters for British imperialists in Canada. In 1894, the British and Japanese governments signed the historic Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation [hereinafter “Anglo-Japanese Treaty”], which began the process of reversing the unequal treaties. The first article of the treaty stipulated that subjects of either country would “have full liberty to enter, travel, or reside in any part of the dominions and possessions of the other Contracting Party, and shall enjoy full and perfect protection for their persons and properties.” [7] The British government invited the Canadian government to enter the treaty as Canada did not enjoy foreign policy autonomy in 1897. Laurier refused, not because of the prospect of unrestricted Japanese immigration, but rather on the grounds that the most-favoured nation clause would hurt the Canadian economy. Despite Canada’s non-adherence to the Anglo-Japanese Treaty, Laurier’s Liberal government disallowed B.C.’s anti-Asian statutes ostensibly to avoid embarrassing Great Britain and its important ally, Japan. [8] Pro-British imperialists were in a bind. They often loudly petitioned their elected provincial and federal representatives to enact policy that demonstrated Canada stood side-by-side with Britain (such as sending troops to fight in the Boer War). Yet even though Canada would not adhere to the Anglo-Japanese Treaty until 1906, B.C.’s anti-Asian statutes drew the Japanese government’s ire and reflected badly on Canada as a member of the British Empire.

In light of the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance and Japan’s stunning military victory over Russia in 1905, the Laurier government decided it was time to forge closer ties with Japan, the newest member of the Great Powers circle. In 1903, Minister of Agriculture Sydney Fisher, enticed by the commercial possibilities, held talks with Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro that ended in failure. Fisher wanted a new treaty, but Komura would not consider it. The Foreign Minister did allow the Canadian government to join the existing 1894 Anglo-Japanese Treaty if it desired, which the British Foreign Office permitted in 1905. As the contents of the treaty would not change, the Foreign Office reminded Laurier that “Japanese subjects” would have “full liberty” to enter Canada. [9]

In a personal bid to change the provisions regarding Japanese immigration, Laurier decided to confer directly with the Japanese Consul-General, Nosse Tatsugoro. Nosse assured Laurier in 1905 that “the Japanese government will always adhere to their policy of voluntary restrictions on their people emigrating to British Columbia.” [10] Nosse was referring to the Meiji government’s pre-1905 lukewarm position on emigration to North America (excluding Hawaii). But, as Lemieux would discover during his visit to Japan, Nosse failed to consult with the Meiji Government whether this was still official policy. When Canada adhered “unreservedly” to the Anglo-Japanese Treaty in 1906, the Consul-General’s promises were not appended or mentioned in the official documents.

Almost immediately after adherence to the treaty, thousands of Japanese arrived in Vancouver. Though some were in transit to the United States and some were returning from a trip to Japan, the sight of so many Japanese angered various sections of British Columbia society. In Vancouver, fears of an “Asiatic invasion” boiled over on 7 September 1907. [11] A mob led by the Asiatic Exclusion League destroyed Chinese and Japanese property in Vancouver and there were many wounded.

The Japanese Foreign Minister, Count Hayashi Tadasu, suggested avoiding “the usual diplomatic channels” and hoped Canadian authorities could settle the issue of damages and reparations “independently of the British government.” [12] Laurier wasted no time in sending his regrets to the Consul-General and the Imperial Japanese government, while he appointed Deputy Minister of Labour W.L. Mackenzie King as Royal Commissioner to investigate the damages in Vancouver.

“The influx of Oriental labour,” in the popular phrase of the day, clearly violated Nosse’s promises. Laurier considered sending a diplomatic envoy to Tokyo and the Cabinet endorsed Rodolphe Lemieux as the government’s chief envoy. The French-Canadian Lemieux was one of Laurier’s most trusted ministers. The object of Lemieux’s mission was to obtain written assurances from the Japanese that they would not allow more than 300 labourers and artisans a year to emigrate to Canada. Even though the first article of the Anglo-Japanese Treaty stated that the Japanese enjoyed “full and perfect protection for their persons and properties,” and that the race riot had clearly been caused by Canadian and American agitators, by sending Lemieux on his mission, Laurier essentially shifted the blame to the Japanese. The large “unassimilable” Japanese presence in Canada had caused the riot, not the violent white nativists. If mother Britain were not dependent on Japan’s goodwill and military presence to protect its commercial and colonial interests in East Asia, Laurier would surely have made even more stringent demands on Japan to restrict emigration, in order to satisfy his B.C. constituents, or even the Governor-General of Canada, Lord Grey. [13]

The Lemieux Mission, November – December 1907

Lemieux set sail on 29 October 1907 and arrived in Yokohama on 14 November. The British Ambassador to Japan, Sir Claude MacDonald, lent the Lemieux team invaluable diplomatic help. MacDonald introduced Lemieux to Foreign Minister Hayashi and the first official meeting was scheduled for 25 November. Lemieux understood Laurier’s request but he also had a keener understanding of the difficulties of imposing such strict demands on a British ally and an emerging world power. As Lemieux observed, with the signing of the Anglo-Japanese Treaty, “Jap[an] gained admittance [into the] Comity of Civilized nations on a status of Equality.” [14]

During his trans-Pacific voyage, Lemieux prepared for his meeting with the Foreign Ministry by reading a confidential report on the situation in B.C. written by a W.E. McInnes, who was sent at the behest of the Minister of the Interior, Frank Oliver. The report had a major impact on Lemieux’s thinking on racial matters in Canada, as he had virtually no first-hand knowledge of anything Asian. The crux of McInnes’s findings, which Lemieux studiously jotted down, rested on the opinion that Japanese immigration to Canada, whether large-scale or not, was primarily a racial issue which threatened to destabilize Canadian society. Lemieux noted how the Chinese, while paradoxically unwelcome as immigrants, were actually highly desirable workers. “[The] Chinese [were] less objectionable” and “in demand” because they did menial, dirty, and dangerous jobs, which he listed as “domestic servants, laundry men, cooks, labourers in clearing forests, market gardeners, inside workers in canneries [and], above ground workers in collieries.” [15]

On the other hand, objections were raised against the “unassimilable” Japanese because they were doing too good a job at integrating in Canadian society. The Japanese, Lemieux wrote in his notes, were more competitive, had “more energy,” and had “more independence than others.” He then listed the different sectors where Japanese were employing their “competitive” spirit: fisheries, lumber industries, boat building, mining industry, railways, sealing, domestic servants, market gardening), farming, land clearing, tailors, waiters, and finally, the all-encompassing “engaged in business.” [16]

The Japanese faced more hostility from whites in B.C. than the Chinese or Indians, even when they were employed in the same sectors, because the former’s enterprising attitude represented a clear threat to established notions of the superiority of the white race. That threat is clearly demonstrated in McInnes’s report:

“There is an uneasiness in British Columbia to-day that would not be felt if the Asiatic immigration were confined to Chinese and Hindoos, who are looked upon the whites as greatly inferior races.[…]The Japanese do not confine themselves to limited and subordinate occupations as do the Chinese and Hindoos. The Japanese are competing with white merchants for white trade; they are competing with white artisans and clerks for work and employment in every line of activity. I visited the town of Steveston, where formerly over 3,000 white fishermen earned their living; they have been entirely supplanted by the Japanese. Steveston is now to all intents and purposes a Japanese town.” [17]

The Japanese work ethic and enthusiasm clearly represented the kind of labour Laurier needed to fulfill his promise of a strong and economically vibrant 20th century for Canada. However, their presence on Canadian soil manifested another unique, though ill-defined, problem. According to his notes, the large-scale presence of “Mongolians” in “an Anglo-Saxon country” was “fraught with danger.” These “races [were] unfamiliar” with “democratic institutions,” and thus threatened – though he never explained how – British and Anglo-Saxon civilization. Although he noted that the ratio of whites to Asians in B.C. was an alarming “1 in every 4,” he concluded that the “reason for restriction [was] far more compelling[.] Orientals belong to a civilisation radically different than ours. Well nigh impossible gulf between the 2[.]” McInnes invoked stronger imagery when he observed that “the whites fear that in a very few years, under existing conditions, that ratio will be so decreased as to make British Columbia an Asiatic Colony.” [18]

At their first official meeting, Lemieux’s memorandum attempted to bridge the “well nigh impossible gulf” between the Canadian and Japanese representatives. After insisting that the Japanese abide by the “Nosse promises” and limit emigration to Canada to 300 labourers and artisans a year, Lemieux attempted to flatter his hosts by emphasizing the history of goodwill and cordial relations between the two countries. On this matter of “goodwill,” Lemieux pointed out that the Laurier-led federal government had disallowed 22 of B.C.’s anti-Asian statues in the last ten years, including nine that specifically restricted Japanese immigration. As Iino Masako points out, Lemieux’s statement was disingenuous. The real pressure to disallow B.C.’s legislation came from the Japanese government, via the British authorities in London, rather than the federal government’s own sense of outrage over the discriminatory legislation. [19] Furthermore, Lemieux was pleased to announce that his government had approved a compensation package worth $9175 to the Japanese community and $1600 for the Japanese Consulate’s legal costs. Lemieux’s intention was to demonstrate that the Canadian government could and did differentiate racially between the Japanese and the Chinese (if only for diplomacy’s sake), even if British Columbians only saw “Orientals,” “Asiatics,” and “Mongolian hordes.”

Hayashi and his Vice-Minister the Baron Chinda dismissed the Canadian Minister’s case. First, according to Chinda, Consul-General Nosse was “not authorized to give such assurance” in promising restrictions on emigration. This had been Lemieux’s strongest argument and Chinda’s remark suddenly invalidated the diplomatic and legal grounds of Lemieux’s case. Second, Hayashi promised to study Lemieux’s memorandum but he warned the Canadian that the Japanese people “were high spirited and sensitive” and they would not look favourably towards a treaty which limited their freedom to emigrate, and “that they could not tolerate being regarded as inferior to other races against whom no other restrictions were enforced.” [20] In this respect, Hayashi taught his Canadian and British guests a history lesson. When the American Commodore Matthew Perry opened Japan to the Western world in 1853, he told the Japanese that “the only way” they would elevate themselves among the world’s nations would be by “welcoming all races to their shores.” Fifty years later, Japan’s ports were open to Americans and other Westerners while Asian “races” had the immigration “door shut in their faces.” [21] This example of American (and by extension Canadian) hypocrisy was not lost on Lemieux. He came to appreciate the tensions his government’s efforts to treat Japanese immigrants as third-class (after the British and other white Europeans) were having in Japan.

Count Hayashi returned a week later to announce that while the Japanese government could not enter into a new treaty, it “acknowledged our difficulties in [Canada]” and was thus prepared to limit emigration. [22] In truth, bearing in mind its relationship with Britain and the situation in British Columbia, the Japanese had very few available options. Even though the Japanese government stood on the legal high ground, it could not possibly ask for the status quo vis-à-vis Canada. To do so would invite more physical harm and discriminatory legislation against Japanese residing, or desiring to reside, in Canada. For the Japanese to go against the Canadian government’s express wishes might alienate Great Britain, their powerful ally. Yet to accept Canadian demands would be to acknowledge that, despite their newfound Great Power status and alliance with Great Britain, they were considered an “inferior race” and lumped in the same category of unwanted people as the Chinese and the Indians. Hayashi accepted the Canadian demands because while the restrictions were insulting and their treaty rights violated, there were other places where Japanese labour could emigrate and make a valuable contribution, such as Korea, Manchuria, and South America. [23]

Rodolphe Lemieux, Claude MacDonald, Joseph Pope (the Canadian undersecretary of State for External Affairs), and Ishii Kikujiro (then Director of the Bureau of Commerce of the Foreign Ministry) drafted a proposal on December 4 that would become the basis for the Lemieux Agreement. The wording of the proposal conveyed a stronger sense of racial exclusion than even Lemieux had originally suggested. Whereas Lemieux had demanded a limit of 300 labourers and artisans per year, according to the proposed draft, all Japanese emigration would be forbidden. Only four exemptions were made: 1) current Japanese residents of Canada; 2) domestics for Japanese residents; 3) contract labourers requested by Japanese residing in Canada or by Canadian nationals, who then needed the Canadian government’s approval; and 4) agricultural workers or miners for Japanese-owned farms and mines. [24] Rather than change the treaty, the Japanese government would send a letter detailing these instructions to the British Ambassador and the local Consular authorities. [25] These four exceptions had a dual purpose. Those few permitted to emigrate would be working on the margins of the Canadian economy. Furthermore, the restrictions indicated a desire to segregate Japanese workers and their community from the white community. Both Lemieux and MacDonald urged their respective superiors to approve the proposals. [26]

Laurier was not satisfied and he replied with a curt message: “Proposed arrangement not satisfactory.” [27] While the terms seemed agreeable, Laurier insisted on a written document that he could introduce to Parliament that promised Japan would enforce a fixed number for emigration. The Japanese government, fearing a public backlash not unlike the 1905 Hibiya riots [28], would not sign such a document for public demonstration. Lemieux relayed to his prime minister how important it was to approve the current proposal, as the Japanese government could not do more to satisfy Canada. As Laurier was so far from Japan, Lemieux wrote, he could not appreciate that the Japanese were “very proud and very sensitive as regards the racial issue.” The press “was up in arms against any proposed arrangement.” Finally, Lemieux made it very clear the essential difficulty in realizing the goals of his mission: “[The] Japanese Government will not in any event permit a foreign Government to discriminate against their subjects.” [29]

Stuck between his government’s refusal to accept any proposal until it could speak with Lemieux and a Japanese government that would not include numerical limits, Lemieux left for Canada on December 26 disappointed at not having completed an agreement in Japan. But as historian Patricia Roy notes, based on initial despatches from Tokyo, British Columbians were wary of the progress Lemieux had made in Japan. Pressure from B.C.’s Members of Parliament required Laurier to present a document outlining Japan’s firm intention to restrict emigration. But after he returned to Ottawa in January 1908, Lemieux explained the details of the proposal. The Cabinet approved Lemieux’s arrangement with the Japanese government and this became known as the “Lemieux Agreement.” There were some initial fears that the Japanese had ignored “the spirit and title of the agreement” when hundreds of Japanese arrived at Vancouver in the first half of 1908. This led to the appointment of the ex-Liberal politician R.L. Drury to supervise immigration from Japanese ports. However, from May 1908, Japanese immigration ground to a halt and less than 50 left for Canada over the next six months. [30] The Lemieux Mission, in the opinion of B.C.’s white community, had clearly been a success.

Comparing Canada in 1907 with Japan in 2007

Though on the surface, Canada in 1907 and Japan in 2007 appear to bear little in common, the issue of race as a determinant in national politics unites them both. Furthermore, the events surrounding the Lemieux mission and the new Japanese immigration procedures both employ the rhetoric of fear, a false sense of racial unity for political gain, and a disregard for treaty (or human) rights.

It is significant that the Lemieux mission occurred during a decade when the federal government actively sought hard-working people to settle the vast, underpopulated prairies. Even though the Japanese, in particular, possessed the skills and the work ethic that a developing Canada needed, their race, their “unassimilability,” and their “competitiveness” were not welcome to a white, primarily Anglo-Saxon, country.

It seems odd today that in a young country like Canada, where there was a desperate need for skilled labour, that politicians, newspapermen, and labour leaders would turn away the very people they needed because they were “evidently in some trades our superior.” [30] Yet the construction of a white Anglo-Saxon country, rather than the construction of an economically strong country which could develop its vast natural resources and compete with its American neighbours, dominated the rhetoric of Canadian political and labour leaders. With a large presence of French-Canadian Catholics, among other ethnic and religious groups, an Anglo-Saxon Canada was neither demographically nor politically feasible. Despite Canada’s multi-ethnic community, it was easy to play the race card for political gain in the era of Social Darwinism and “Yellow Peril.” This was particularly true case in British Columbia, which was on the front lines of Asian immigration. The white Anglo-Saxon leaders of B.C. used the baseless rhetoric of fear (“hordes of Orientals” who drove down wages) to rally their fellow Canadians to the cause of Asian exclusion and discriminatory immigration legislation. While the Lemieux mission targeted only Japanese migrants, it was one part of a larger effort by provincial and federal governments to bar Asian peoples from settling on Canada’s shores.

Japan’s new immigration policy, on the other hand, entails racial discrimination on a large scale, as virtually anyone who is not of Japanese blood now undergoes immigration procedures that treat them as potential terrorists and criminals. That such draconian measures could be accepted with so little political debate owes to this century’s new rhetoric of fear, the asinine “war on terror.” In Japan as elsewhere, the “war on terror” has inspired governments to scale back human rights in the name of protecting their borders. Coupled with the belief of Japanese superiority and racial homogeneity (ware ware nihonjin [“We Japanese”] and nihonjinron [“Theory of Japanese-ness”]), the Japanese government has created an immigration system that demonizes all foreigners under the pretext of appearing “strong” in the fight on terrorism.

The issue of skilled labour is another area where Canada in 1907 and Japan in 2007 have similarities. Canada sought skilled labour to develop its young country. Japan today is facing a skilled labour shortage, particularly in the health-care sector [32] and has already had the first absolute population decline in its modern history. Unlike the terms of the Lemieux Agreement, the new immigration procedures do not automatically bar anyone from entering Japan per se. But they have caused such hostility among human rights groups and businessmen, that Japan’s tactics might have significant long-term consequences. The latter say they will consider moving their business to Seoul (Incheon), Singapore, or Hong Kong, a decision that makes geographical sense as China and India experience explosive economic growth. It remains to see whether other skilled workers, particularly nurses and other health-care workers, will turn away from Japan in search of opportunities elsewhere.

In the same vein, both 1907 and 2007 share the honour of incurring the wrath of the people of Great Power/Western countries. The Japanese, having recently attained Great Power status, protested vigorously at being treated in the same fashion as the Chinese or Asian Indians. They held rights enshrined in a British treaty that permitted them “full liberty” to travel and reside in Canada. Thus the Japanese rightly expected to be treated with the dignity inherent of being subjects of an Imperial Power and allied to another Great Power, but they were rudely jolted from that notion very quickly. In 2007, human rights groups like Amnesty International, ordinary “foreign residents” of Japan, and frequent visitors to Japan protested loudly to the media and to their governments about this overt discrimination and infringement on human rights. Despite the Japanese protests in 1907, the Lemieux Agreement remained in force until after the Second World War (the annual limits were actually tightened from 400 to 150 in 1923). The Lemieux Agreement was initially enforced to keep Canada, particularly British Columbia, “white” and to quell labour’s fear of “unfair competition.” It endured for nearly 40 years because there was no political will in Canada, or elsewhere in the white Western world, to end the measures. Similarly, in the current global political climate of the “war on terror,” it is unlikely that the new immigration procedures will be repealed, for fear of appearing “weak” on terrorism. Nonetheless, Justice Minister Hatoyama would do well to remember how the geta was once on the other foot, when Canada and the United States indiscriminately targeted the Japanese as the source of their domestic ills for political advantage.

Simon Nantais is a doctoral candidate in Japanese history at the University of Victoria (Canada). He is currently a Japan Foundation Doctoral Research Fellow at the Ritsumeikan Center for Korean Studies in Kyoto. His research deals with the Korean community in the Kansai area during the American Occupation of Japan (1945-1952). He would like to express thanks to Professors John Price and Patricia Roy for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper, and to Professors Mark Selden, Nobuko Adachi, and Jim Stanlaw for their comments and suggestions. He would like to thank Takuya Tazawa for invaluable research assistance.

This article was written for Japan Focus and posted on January 21, 2008.

Notes

[1] In addition to dozens of letters to the editor, see Kevin Rafferty, “Not so welcome to Japan any longer,” The Japan Times, 1 November 2007.

[2] Jun Hongo, “Hatoyama in hot water over ‘al-Qaida connection’,” The Japan Times, 30 October 2007.

[3] This is reminiscent of the post-9/11 “guilt trip” the Bush Administration played on Canadians. It was “Canada’s porous border” that allowed terrorists to enter the United States; it was “Canada’s leaky immigration system” that admitted in terrorists who lived next to the United States. Lawrence Martin, “Spin game: the great Canadian guilt trip,” The Globe and Mail, 3 October 2001, p. A15.

[4] For the authoritative interpretation of the Vancouver Riot, see Patricia E. Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989), chapter 8.

[5] Masako Iino, “Japan’s Reaction to the Vancouver Riot of 1907,” BC Studies 60 (Winter 1983-1984): 36.

[6] Iino, 35-36.

[7] Honorius Lacombe, “La mission Lemieux au Japon (1907-1908).” MA Thesis, University of Ottawa, 1951, 7. Originally quoted from British and Foreign State Papers, 1893-1894, vol. LXXXVI, A.H. Oakes and Maycock, eds. (London: Willoughby, 1904), 40.

[8] The Canadian government, however, had no diplomatic qualms about offending the Chinese, as the head tax attests.

[9] Robert Joseph Gowen, “Canada and the Myth of the Japan Market, 1896-1911,” The Pacific Historical Review 39, no. 1 (Feb. 1970): 72-73.

[10] Letter from Nosse to Laurier, no. 97258, 8 May 1905, Sir Wilfrid Laurier fonds (MG26-G), Library and Archives Canada [LAC].

[11] Three days earlier, there had been an anti-Asian riot in nearby Bellingham, Washington, and there had been a number of anti-Asian riots across the Pacific states in 1907.

[12] Sessional Papers, No. 74b, 165, quoted in Howard Sugimoto, Japanese Immigration, the Vancouver Riots, and Canadian Diplomacy (New York: Arno Press, 1978), 159.

[13] The Governor-General of Canada, Lord Grey, took a keener interest in Canadian affairs than most of his predecessors. In an undated letter sent to Lemieux prior to his departure, Lord Grey, ostensibly speaking on behalf of the British Crown, warned that “The real danger to B.C. and Canada will not come from the officially permitted influx [of] Passport [holding] Japs into the mainland of B.C. – but from the possible occupation by nonofficial Japs of the rich and uninhabited Islands like Queen Charlotte Islands[.] I am much alarmed with possible consequences of a Jap invasion of these unoccupied lands.” Letter from Lord Grey to Lemieux, 140, vol. 3, Rodolphe Lemieux fonds (MG 27 II D10), LAC.

[14] Lemieux notes, 148, vol. 3, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[15] Lemieux notes, 146, vol. 3, Lemieux fonds, LAC. Menial, dirty, and dangerous jobs are the kitsui, kitanai, kiken (the 3Ks) that the Japanese today say they will not do. The McInnes report and comments from British officials can be found at 326-331, 2 October -28 November 1907, F.O. 371/274, Public Record Office. I used British Foreign Office Japan Correspondence, 1906-1929 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1988) to locate the McInnes report.

[16] Lemieux notes, 150, vol. 3, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[17] W.E. McInnes to Frank Oliver, 328, 2 October 1907, F.O. 371/274, Public Record Office.

[18] Lemieux notes, 151, vol. 3, Lemieux fonds, LAC; McInnes to Oliver, 328, 2 October 1907, F.O. 371/274, Public Record Office.

[19] Iino, “Japan’s Reaction to the Vancouver Riot,” 35-36.

[20] Precis of interview with Count Hayashi at the Foreign Office, 255, 25 November 1907, vol. 4, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[21] Ibid., 256.

[22] Precis of the meeting held at the Foreign Office at Tokio, 370-372, 2 December 1907, vol. 4, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[23] Around the same time the Lemieux was in Japan, President Theodore Roosevelt’s Administration and the Japanese government exchanged a series of notes which effectively ended Japanese emigration to the U.S. (but not, for the moment, to Hawaii). Japanese authorities did not issue passports to people wishing to work in the United States. This became known as the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement.

[24] Precis of the meeting held at the British Embassy, 406, 4 December 1907, vol. 5, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[25] Telegram from Lemieux to Laurier, 472, 10 December 1907, vol. 5, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[26] Telegram from Lemieux to Laurier, 438, 6 December 1907, vol. 5, Lemieux fonds; Paraphrase of telegram from Sir C. MacDonald to Sir E. Grey, 421, 5 December 1907, vol. 5, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[27] Telegram from Laurier to Lemieux, 441, 8 December 1907, vol. 5, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[28] The Japanese public had been led to believe that Japan would get all of its demands at the Portsmouth Treaty negotiations, which officially ended the Russo-Japanese War, when in fact the Japanese government’s position was not as strong as it or the press claimed. When the disappointing terms were announced, a mass rally was held in Tokyo on 5 September 1905 against the Japanese government for concluding the Treaty. The next day, the day the Treaty was signed, riots broke out across Tokyo and over 350 buildings were destroyed, including the official residence of the Home Minister. In dealing with the Canadian immigration question, the Japanese government refused to present a document to the public outlining restrictions imposed on its subjects. They feared similar violence if the terms were announced. For an analysis of the 1905 Hibiya Riot, see Shumpei Okamoto, The Japanese Oligarchy and the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970).

[29] Telegram from Lemieux to Laurier, 468-470, 10 December 1907, vol. 5, Lemieux fonds, LAC. About a week later, Lemieux sent Laurier another cable explaining how Japanese feelings of maintaining racial dignity were at the core of their refusal to include numerical limits in any negotiated proposal. He wrote: “Japanese Government offer to insert in confidential letter to [British] Ambassador expression of their confident expectation that united immigration domestic and farm hands will not exceed four hundred annually. While in opinion of Ambassador and myself they are perfectly sincere in this and in their fixed purpose voluntarily to restrict immigration within limit acceptable to us, they cannot possibly give any written assurance of numerical limitation. Any limiting of treaty rights would mean their defeat and perhaps lead to serious trouble. Feeling very high.” Telegram from Lemieux to Laurier, 622, 19 December 1907, vol. 6, Lemieux fonds, LAC.

[30] Roy, A White Man’s Province, 211-213.

[31] Ibid., 211.

[32] See for example the following recent reports: “OB-GYN career shunned by med students,” Japan Times, 16 November 2007; “Coping with the doctor shortage,” Japan Times, 1 October 2007; “Japan physician shortage serious: OECD,” Japan Times, 26 July 2007.