Asahi Shimbun

Japan Focus introduction. Below are the first two in a twenty-one part series published by the Asahi Shimbun and International Herald Tribune on May 23, 2007 that seeks to chart Japan’s role in shaping the world’s future. The Asahi editors target the twin dangers of militarism, particularly nuclear weapons and global warming, at the center of their effort to frame an appropriate role for Japan in the coming decades. These are indeed two of the most intractable issues facing the Asia Pacific and the world. Yet the series nowhere confronts the central obstacles to an expanded Japanese contribution toward peaceful resolution of global problems: that is Japan’s subordination within a US-Japan security relationship. Nor, in reaffirming Article 9, does it address the implications of the US-Japan relationship or Japan’s contemporary drive for a more powerful, expansive, and constitutionally mandated military role. It remains, in short, at the level of rhetorical commitment to “peace” without engaging the intractable geostrategic issues that challenge peaceful outcomes, above all the nature of US global power and Japan’s subordination to it. The point was made clearly by Terashima Jitsuo, President of the Japan Research Institute (Nihon Sogo Kenkyujo). Responding to questions from an Asahi editorial staff member about the value of a China-Japan-US meeting, Terashima commented, “So long as Japan is viewed both by the US and China as a peripheral country attached to the US, then materialization of a China-Japan-US meeting is far off.”

Likewise, in broaching environmental issues, the Asahi series nowhere suggests how Japan, which appears to have effectively abandoned in practice, if not in rhetoric, even the modest Kyoto targets, can contribute to halting the expansive carbon emissions development strategies that ultimately must be tackled globally. This means recognizing, and acting to halt, the reckless energy policies pursued by the US, followed by addressing the challenges posed by such high growth countries as China and India. As Michael Klare pointed out, the Pentagon alone consumes, by the most minimal estimates, 1.3 billion gallons of oil annually, more than the 150 million population of Bangladesh. At a time when Japan has relinquished much of its earlier leadership in energy efficiency, and with a government that, like the US, rejects compulsory or even economic measures to halt and reverse the increase of greenhouse gases, and which has largely abandoned earlier efforts to promote energy alternatives to oil, coal and nuclear power, it is difficult to discern the basis for Japanese leadership. Immediately following publication of the Asahi series, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo made his first claim to providing Japanese global leadership with a call for 50 percent reduction in greenhouse gases by 2050. In fact the proposal was a mild version of the German proposal. Moreover, like proposals emanating from successive Japanese administrations, and like the Asahi’s call for environmental citizenship, the proposal is without teeth and without so much as a nod at an approach to implementation. It remains, in short, like the Asahi series, at the level of feel-good rhetoric without substance.

What would it take to turn a wish list, which includes such praiseworthy goals as arms reduction, nuclear disarmament, the curbing of carbon emissions, and promotion of East Asian community, into a viable strategy for leadership and international cooperation? The series provides few answers. MS

1. Japan as a Global Contributor: Becoming a global ‘coordinator’

Let’s take a moment to imagine the future.

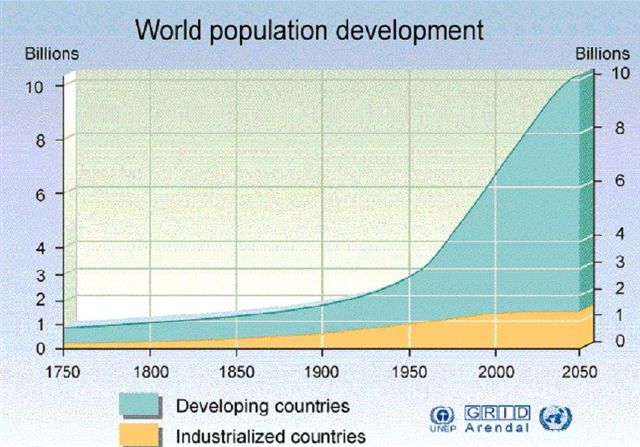

The world’s population, which now stands at about 6.5 billion, could surpass 10 billion by 2045. Economies will balloon accordingly. But will the Earth be able to tolerate such growth?

World population growth 1750 to 2050

There are already concerns regarding diminishing energy, food, water and other resources. In the meantime, global warming is intensifying, adding to those fears. If nothing is done, hundreds of millions of people will likely be affected by water shortages in the 2020s. Many species will likely become extinct and agricultural productivity could drop, resulting in greater threats of starvation.

The world has shrunk. As it became easier for people, money and goods to travel freely across national boarders, the movement of terrorists, drug traffickers, infectious diseases and other negative factors has increased. The 9/11 terrorist attacks were a typical example.

The time of uni-polar domination by the United States will come to an end, while the integration of Europe will probably extend further. China and India are sure to become more powerful. The world will shift more to a multi-polar structure. This is an era in which countries, businesses and people worldwide are becoming connected more diversely, and thus are influencing one another to a greater extent.

National egos often clash, but what is different now from any previous period in the past is that no nation will be able to “protect its national interests” without thinking about the fate of this shrinking world. Fighting for land and resources, and destroying the Earth’s ecosystem for immediate national interest, would simply result in putting a noose around one’s own neck.

Yet, such an era offers an optimal opportunity for Japan to make the most of its inherent characteristics. This is because the country became wealthy as a trading nation through its constant efforts and ingenuity–despite its woeful lack of natural resources.

This being the case, Japan should aim to become a “nation that contributes to the world.”

* * *

A nation that does so is one that seriously ponders issues that affect all of mankind, thereby leading the international community in its efforts to react positively. Japan should try to secure its national interests by looking through this prism. The diagram above lays out the overall concept.

Japan was once an economic powerhouse, but its power is declining in relation to the rapid growth being chalked up by China and India. But if it sticks to self-centered national interest out of a sense of crisis, its influence will shrink and there will be fewer gains.

Instead, we believe Japan should promote a broadening of the “international public good” that can be shared with many countries. We are sure it would be wiser to reap the fruits of such a policy.

Japan excels in efficient energy use. It should extend that expertise to China and India, and other countries that would benefit. Certainly, it would be appreciated by people all over the world. Moreover, it would contribute to the global environment. Japan’s business opportunities would grow, too.

Countries that have disintegrated due to civil wars and other catastrophes often bemoan the fact that the “rule of law” has been undermined.

Terrorists, drug and arms syndicates, and other crime organizations invariably establish a foothold in such countries, using them as bases to spread their evil around the world. Infectious diseases become prevalent and spread across national boundaries. The establishment of the rule of law comes before everything. And this is something that Japan can certainly help to implement.

Japan should increase its aid to developing nations and dispatch many more people to work in international organizations. It should also provide more support to nongovernmental organizations operating abroad and work hand in hand with companies that respect international common interests. Japan should aim to be a “coordinator for the international public good,” so to speak.

In Asia, China and India are becoming regional powers. North Korea has created international tensions by conducting its first-ever nuclear test. There is also a threat of growing nationalism. And while this cannot avoid complicating things, we should not react too strongly to such trends.

Japan should ensure its security on the basis of the Self-Defense Forces and the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. At the same time, Japan should help promote reciprocal relations among Japan, the United States and China, as well as the East Asia community to prevent conflicts in the region. “Institutionalization of trust,” rather than a structure of distrust, would improve common interests in Asia as well as benefit Japan. This concept must also be used to resolve territorial disputes with our neighbors.

Japanese aid being loaded for Iraq

To become a “coordinator” of the world, it is important for Japan to expand and effectively use “international public properties” that would help solve problems, with the United Nations at the core. These include collective security, free trade, conservation of the global environment and humanitarian programs, organizations and treaties as depicted in the diagram below.

Countries like Japan that respect the “rule of law,” without falling into great-power ambitions, would be perfect to nurture such concepts. Japan should combine such “public properties” and make good use of them to work toward global peace and sustainable economic development. Japan should use them to work toward a “J brand” that would embody the nation’s diplomatic efforts.

* * *

Our Constitution is a precious resource in walking such a path. In light of its deep remorse for the past war, Japan has adhered to a course that suppressed military activity to the extreme. At the core of this thinking is the preamble to the Constitution that proclaims internationalism and Article 9 regarding pacifism.

The message of Article 9 is that Japan will never be put in the position of repeating the foolishness of military aggression. Countries cannot help but feel relieved at the provisions contained in Article 9. Certainly, this is particularly helpful with regard to Japan’s relations in Asia. The Japan-U.S. Security Treaty is also important. However, Article 9 is an effective breakwater to maintain an appropriate distance from the United States. Altering Article 9, particularly with regard to upgrading the SDF to a military both in name and in reality, would not be a positive move for Japan.

Nevertheless, it would be desirable to position the SDF under the Constitution. For this reason, The Asahi Shimbun proposes developing a quasi-constitutional basic law about peace and security to clarify the basic characteristics and role of the SDF, thereby keeping it in check at the same time.

Based on the spirit of the preamble and Article 9, Japan must maintain an exclusively defense-only policy. The right of collective self-defense that would result in joining wars with other countries should not be exercised. As the only country to experience the horrors of atomic bombing, Japan should stand firm on remaining nuclear-free. Civilian control is also important. As for international peace-building programs led by the United Nations, Japan should participate in a manner that reflects what the SDF stands for–the fact that it does not contain the word “military” in its name.

The basic law should have these factors as its pillars, as they are directly related to contributing to the world.

This is the first of a twenty-three part series published in IHT/Asahi Shimbun on May 23,2007. The entire series can be accessed here

2. Climate Security: Kyoto the starting point of global environmental conservation

Constrain the average rise in global temperature by 2 or lower degrees.

Set up an energy-saving resource-conservation social model in Japan and popularize it around the world.

Make environmentally friendly businesses more attractive to encourage the United States and China to help prevent global warming.

It’s early May in Kyoto and the Aoi Festival is drawing near. The national leaders visiting Japan are driven through major streets in “eco cars,” vehicles that do not use gasoline. The fresh green colors of spring are in evidence everywhere. The scene is the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Kyoto Protocol, which took effect in 2005.

Keeping such an image in mind for 2015, The Asahi Shimbun wishes to propose putting the prevention of global warming at the center of this country’s national strategy.

Having expressed deep remorse for its actions in World War II that ended following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan has walked the path of peace ever since. Hiroshima was the starting point for postwar Japan. Similarly, Japan should make the Kyoto Protocol its starting point for the 21st century, and for global environmental conservation efforts over the century ahead.

After the end of the Cold War, the global environment became a hot topic in international politics. Today we even have the expression “climate security.” Why climate security?

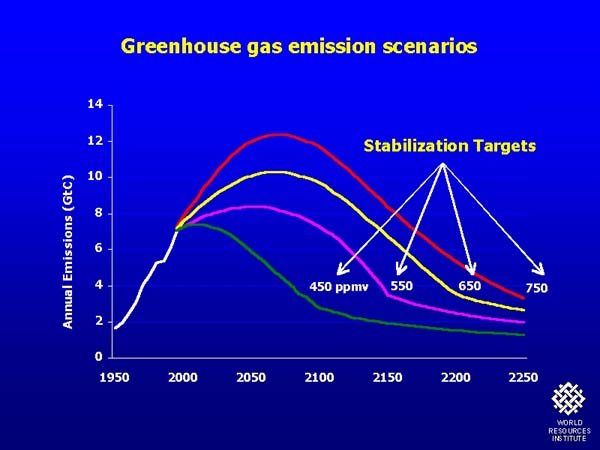

According to the committee report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, whose members are scientists from around the world, if the global economy maintains high economic growth that depends on oil and other fossil fuels, average global temperatures will rise by about 4 degrees by the end of this century from the level at the end of the 20th century.

Kyoto gas emission targets. A pipedream?

What will happen if there is a 4-degree increase?

Serious water shortages would occur in many areas of the world and crop production will decline. More than 40 percent of species will go extinct. Ecosystems will be destroyed, the map of the distribution of infectious diseases will change, and there will be higher risks of catastrophic changes beyond our imagination.

When calculated in monetary terms, the damage will be huge. The Stern Report issued by the British government estimates that with a rise of 5 to 6 degrees in temperature, the global gross domestic product would drop by an average of 5 to 10 percent. Various disparities and conflicts will become more acute, and the whole world may be thrown into chaos.

Tremendous threats are close at hand. How can we defend people’s safety and protect our children and grandchildren from these threats? That is a major security issue, just like war and nuclear weapons.

* * *

The Kyoto Protocol will enter its target period in 2008, during which it obliges industrialized nations to achieve reduction goals for carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions. However, the accord does not include the United States, the world’s largest polluter that accounted for 23 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in 2003. In addition, China, the second-largest polluter at 16 percent, and India at 4 percent, are exempt from emissions reductions because they are ranked as developing nations.

When the first stage of the Kyoto Protocol is completed in 2012, it has to immediately go on to a succeeding framework. This is often called “Post Kyoto.” Japan should play a leading role in efforts to create a more effective framework than was attained in the first stage.

To play that role, Japan must fulfill its own responsibility to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 6 percent from the 1990 level. Then, it should reach out to the United States and get it to join in the efforts. Momentum for countermeasures against global warming is mounting at the state level and in Congress. Against the background of this internal pressure, Japan should urge the United States to return to the accord. Then Japan should encourage China, India, and other countries to assume obligations to reduce emissions.

Today, a low-carbon movement that aims not to emit CO2 is starting to accrue great economic value around the world. If emissions-control measures take more effect in each country and emissions trading takes root, having energy conservation and other technologies that slash emissions would become an important pillar in supporting economic competitiveness.

For China and India that aim to become next-generation economic powers, it would be essential to be competitive in moving away from carbon emissions. It may be a heavy burden to have the responsibility to reduce emissions thrust upon them; however, it would benefit them in the long run. This is where Japan’s diplomatic capabilities and persuasiveness can be put to the test.

Even after 2013, the spirit of the Kyoto Protocol should be continuously nurtured to develop a more detailed framework. Meetings should be held in Kyoto, and the “Kyoto” brand should be utilized as the focus for international relations on environmental issues. Japan should start by strengthening unity among industrialized nations at the Group of Eight summit to be held in Toyako, Hokkaido, in 2008.

* * *

Japan should also set a target to limit temperature rise to “within 2 degrees” from 20th-century levels.

The European Union has already established a goal to constrain temperature increases to up to 2 degrees from pre-industrial times (about 1.4 degrees from the 1990 level). Our proposal of “within 2 degrees” is not an unrealistic figure.

To achieve that goal, people will have to make changes to their lifestyles in accordance with a “low-carbon” policy. Despite likely differences in measures between industrialized nations and developing countries, it basically entails a transition from heavy resource consumption to a conservation model. Japan should use its leading energy conservation and natural energy technologies to draw up a blueprint and execute it as an example for the rest of the world.

Energy conservation also reduces expenses. Solar and wind power generation are more suited to countries with large territories and will certainly draw attention from countries such as China and India. Japan must not only sell its technologies but also promote the spread of their use while making the most of official development assistance.

It is also important to support the movement away from carbon emissions using market forces. The EU leads in this respect. Using an emissions rights trade system, it allocates emissions quotas to power plants, ironworks, and other facilities, and allows them to trade their rights. Similar movements are under way in some states in the United States.

A society in which such a movement away from carbon emissions earns money should be established, and such businesses must be promoted. Japan should follow the global trend and promote the development of a resource-conservation society and an emissions quota trading system. It should also encourage China, India, and other developing nations to join the effort. If the United States sees immense business opportunities there, it would come forward on its own to join the accord.

Climate security over several centuries requires diplomatic capabilities to change values on a global scale.

Japan should take the lead in this endeavor.

The complete series is available here .