Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.

Sato Manabu

Translation and Introduction by Gavan McCormack

On December 16, 2012 the Abe Shinzo-led Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) trounced Noda Yoshihiko’s governing Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in elections for the Lower House (House of Representatives) of the Japanese Diet. The landslide victory, delivering Abe (and his coalition partner, New Komeito) 325 of the seats in the 480 member House of Representatives (294 LDP plus 31 New Kometo), opened the way to the second Abe cabinet (following the Abe government of 2006-7). It was remarkable in several ways.

Firstly, it was, in a sense, unconstitutional, according to Supreme Court rulings that the regional discrepancy in the value of a single vote under the current electoral system is too wide.[1] But virtually no one paid this any attention. Secondly, forty-one percent of the voters (roughly 11 million people) did not vote at all, a higher absentee figure than in any post-war election, and of the 59 per cent that did vote, less than 30 per cent favoured Abe (in the proportional sector the figure was 27 per cent). Thirdly, the LDP vote actually crashed even when compared with 2009 (a disastrous year that saw the DPJ achieve its landslide victory), from 33.4 million votes in the local constituency sector to just 25.6 million, and its proportional bloc from 18.8 million to 16.6 million. Its victory therefore rested on unprecedented mass absenteeism and the collapse of the DPJ rather than positive endorsement of its agenda.[2] Fourthly, especially notable was that young people, who will determine the country’s future and bear the burdens created by their elders of this and previous generations, had little interest in the election. While the figures for 2012 are not yet available, in the 2010 Upper House election the average voter age was 56 and the turnout rate for eligible voters aged between 20 and 24 was 33.68 per cent while for those aged between 65 and 69 it was 78.45 percent. [3] Those with most at stake in the election are less and less involved in it. In 2012 that trend could only have sharpened. Japan faces an increasingly gerontocratic future.

Nowehere in Japan is more affected by this peculiar Abe landslide victory than Okinawa. Okinawa has just five representatives in the 480-seat House of Representatives, and all five of those elected, irrespective of their party affiliation, campaigned in opposition to the policy that all the major parties (including, for several, their own) insisted on: prime consideration in Okinawa to the US military presence and specifically the construction of a new base for the US Marine Corps in Northern Okinawa, regardless of mass opposition.

As the rest of Japan digested the implications of the return to Abe government, the Okinawan media was uniquely dark. The Asia-Pacific Journal gratefully acknowledges the permission of Okinawa International University’s Sato Manabu to translate and publish the following essay, published in the Okinawan daily Ryukyu shimpo, on New Year’s Eve, 31 December 2012. (GMcC)

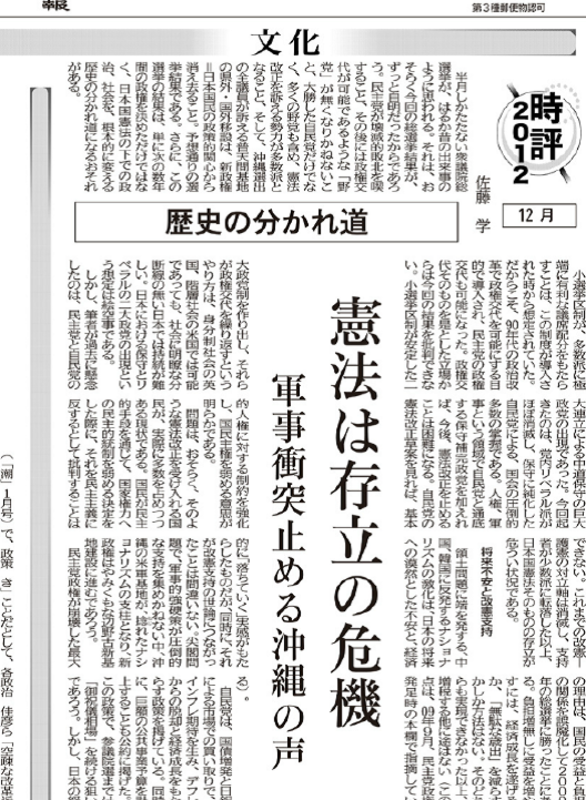

Constitution under Threat

Just two weeks have passed since the House of Representatives election, but it already seems like a long-ago event. That may be because the outcome of this election was long evident. Just as anticipated, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) suffered a crushing defeat, leaving it in such a position that it might not even be able to function henceforth as an opposition party capable of change of government, while forces favouring constitutional revision include not only the hugely victorious Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) but also many others even from the opposition parties. At the same time, the transfer of Futenma Marine base to a location outside Okinawa or outside Japan, supported by all the members elected from Okinawa, has disappeared from the consciousness of the new government and the Japanese people in general. Furthermore, not only does this election result establish the government for the next few years but there are fears that it might constitute a historic turning-point capable of fundamentally changing Japan’s politics and society under the Japanese consttution.

Futenma Base

Ever since the small electorate constituency system was established, it has been understood that it would result in extremely advantageous seat distribution for the major parties. Introduced under the political reforms of the 1990s as part of a design to make change of government possible, it helped make possible the change of government to the DPJ [in 2009]. If one approves in general of the idea of change of government it is hard to criticize the outcome of this present election. If one is in favour of change of government, one cannot object to this particular change, because it has been brought about by reforms (in the 90s) designed to advantage two main parties and to replace the long one party LDP era with a two party system. In short, what those in the 1990s who favoured “political reform” wanted, has come to pass.

However, what has long concerned this author is the possibility of the emergence of a giant centrist party through a grand coalition of the DPJ and LDP. What has emerged now is a Diet overwhelmingly dominated by an LDP that has shed its liberal wing and become almost exclusively conservative. If other, lesser, conservative parties that seem to be in fundamental agreement with it on matters concerning human rights and the military join it, it will be difficult hereafter to block revision of the constitution. Looking at the LDP’s draft constitutional revision, it is clear that it would reinforce limits on fundamental human rights and dilute popular sovereignty.

The problem may be that people ready to accept such revision of the constitution is actually in the process of becoming a majority.[4] Should the people decide by democratic means to weaken democratic controls over state power, it will not be possible to criticize this as anti-democratic. The situation, now that the balance between revisionists and upholders of the constitution has dissolved and upholders have become a minority, is that the very existence of the constitution is threatened.

Anxiety about the Future and Support for Constitutional Revision

There is no doubt that the increasing stridency of nationalism in reaction against China and South Korea, based on territorial problems, has been based on vague anxieties over the future of Japan together with the realization of “economic decline,” and that this is linked to the public opinion in favour of constitutional revision. As military hard-line policies over the Senkaku problem gather overwhelming support, the US bases in Okinawa become a prop for distorted nationalism and the new government is likely to press ahead with constuction of he new Henoko base.

The main reason the DPJ collapsed was because it won the 2009 election through tricking people about the relationship between people’s interests and obligations. There was no way to increase benefits for the people without increasing burdens too except by either accomplishing economic growth or cutting “unnecessary expenditure.” Since neither of these proved possible there was no alternative to increasing taxes, a point that I made in this column at the time the DPJ took government in September 2009.

The LDP has floated policies of accomplishing escape from deflation and stimulating economic growth by encouraging inflationary expectations through increase in bond issues and market interventions by the Bank of Japan. At the same time, it has pledged to greatly increase public works expenditure. It aims to maintain a “honeymoon market” until the forthcoming House of Councillors election (summer 2013). However, the current economic stagnation is not caused by a high yen or insufficiency of money supply. Tried and familiar growth policies are of no use so long as there is no change in the condition of society with too few children and an aging and shrinking population, and with the electronic and auto industries that were once the mainstay of the economy losing their international competitiveness.

Japan’s misfortune is that it has not produced true “economic conservatives.” The economc policies of the DPJ are completely different from an economic conservative position and are really just like those of the LDP in the sense of “postponing the burden.” Furthermore, since the conditions for growth are absent, the possibility that stable economic growth might result from such policies is so low as to be almost zero. The situation cannot long continue in which the people’s wealth is used to sustain the national debt.

The Classic Escape Route

When there is no way forward, what will the LDP government do? I have no wish to entertain such a thought but the classic escape route is war, the calculation that the people’s dissatisfactions can be diverted into an eruption of nationalism, and that Japan absolutely could not lose such a war because there is the Security Treaty with the US and the US would support Japan in any such war with China. Whether from history or from the contemporary world, we can see so plainly that it almost painful just how irrational human beings can be, and there is no guaranteee that today’s Japan will not go this route.

How can we change the way forward for Japanese society and politics? Might it not be the case that only Okinawa, which knows that even if money is spent constructing a new base at Henoko the US is not going to support a war with China, can put a stop to this mistaken path? If it fails to achieve this, an armed clash over the Senkakus would put Okinawan lives at risk and bring our economy to collapse.

Okinawa can avoid a worst case scenario by continuing to insist on its rights based on principle and keeping up its resistance to the idiotic policy of pouring monies into the wasteful Henoko project. For Okinawa’s tiny minority of the Japanese people, this is a most difficult path. However, if we surrender, that would spell the end. We have to believe in the strength of the voices coming from the Okinawan front-lines.

See in addition the New Year day editorial of the Ryukyu Shimpo, “Okinawa Should Spearhead a Global Drive to Promote Peace,” http://english.ryukyushimpo.jp/2013/01/04/8922/

Author

Sato Manabu is a professor of politics at Okinawa International University. This is his monthly (December) column for the Okinawan daily, Ryukyu shimpo, published on 31 December, 2012. For a 2007 essay by author Sato: “Forced to ‘Choose’ its Own Subjugation: Okinawa’s Place in U.S. Global Military Realignment,” August 27, 2006, http://japanfocus.org/-Sato-Manabu/2202

Translator

Gavan McCormack is a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal, emeritus professor at Australian National University, and author, most recently (with Satoko Oka Norimatsu) of Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, Rowman and Littlefield, 2012.

Recent pieces on related subjects:

Roger Pulvers, “The Lessons of the 3.11 Meltdown for Japanese Nuclear Power: Citizenship vs. A Corporate Culture of Collusion,” Dec. 23, 2012, http://japanfocus.org/events/view/164

Martin Dusinberre “Mr. Abe’s Local Legacy and the Future of Nuclear Power in Japan,” Dec. 23, 2012, http://japanfocus.org/events/view/165

‘Jinbo Taro, “The Second Time as Farce?’ Abe Shinzo’s New Challenge,” Dec. 24, 2012, http://japanfocus.org/events/view/166

Gavan McCormack, “Abe Days are Here Again – Japan in the World,” December 24, 2012.

http://japanfocus.org/-Gavan-McCormack/3873

[1] On the so-called “malapportionment” problem, see “Elections in Japan,” Wikipedia, (27 December 2012), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elections_in_Japan/

[2] Compiled from contemporary media sources, notably “Hirei daihyo wa kinki nozoki jimin shui, tokuhyoritsu 27%, sanpai zenkai nami,” Nihon Keizai shimbun, 18 December 2012. http://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXDZO49683680Y2A211C1M10700/

[3] Reiji Yoshida, “Election 2012 – Older voter glut helps politicians avoid long-range problems,” Japan Times, 14 December 2012.

[4] Asahi shimbun reported on 17 December the result of a survey of the newly elected Diet members, finding that 89 per cent favoured constitutional revision and 79 per cent affirmed the Japanese right to participate in “collective security.” (“Shudanteki jieiken 8 wari ga yonin, shuinsen tosensha,” Asahi shimbun, 17 December 2012.) (Translator’s note)

Original editorial: