Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.

Sabine Frühstück

The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force public relations channel (https://www.youtube.com/user/JGSDFchannel; for the English version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tT63npchUM) recently announced in an illustrated video showing the GSDF in action that, according to the new National Defense Program Guidelines for FY 2014 and Beyond, Japan is building a “Dynamic Joint Defense Force.” As such the SDF will emphasize “readiness, sustainability, resilience and connectivity in its software and hardware, supported by advanced technology and C3I (Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence) capabilities, also laying a wide range of foundations for JSDF’s operations.” The grand and stylish 15-minute film is perhaps the most combative piece of public relations issued by the SDF thus far. There is talk of a “tough & resilient Japan Ground Self-Defense Force” and “effective deterrence and response” capabilities. The SDF do not just appear perfectly aligned with the USFJ. The USFJ look as if they were but one branch of the Japanese armed forces.

To my knowledge, never before has the SDF public relations apparatus officially dared to adopt the hawkish rhetoric of becoming “more battle oriented,” speaking of “combat vehicles” that are needed for “optimizing the force structure from an operational point of view,” or the eventuality of responding “to attacks on remote islands.” The smooth aesthetic, musically dramatized and enhanced with defense rhetoric more similar to American military public relations efforts than anything I have seen before in Japan, is a clear departure from earlier, more amateurish attempts to familiarize a broad audience with the Self-Defense Forces’ mission and style.

Yet, there are familiar messages of disaster relief, peace-keeping and peace-building as well and it is important to note that the Self-Defense Forces’ range of public relations techniques and strategies have been more varied than those of many other military establishments, sometimes to the point of conveying rather contradictory messages. Furthermore, style and rhetoric have significantly evolved since the end of the cold war. Numerous political, technological and social factors contributed to this change. Internationally, Japan drew criticism, even scorn, particularly from the United States, for its primarily monetary contribution to the Gulf War (1990–1991). Domestically, the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations Bill was passed in the Japanese Diet amidst substantial protests as it established the legal grounds for Japan’s first peacekeeping mission in Cambodia that same year. Many similar peacekeeping missions followed. Together with the first international disaster relief mission to Honduras in 1998, the 1990s marked a clear departure from the scope of previous operations. Until then, the Self-Defense Forces had been primarily deployed for domestic community and disaster relief missions.

Despite all those experiences, the SDF were deemed inept and unprepared when the then second-biggest earthquake in Japan’s modern history hit the Kobe area in 1995. They would only recover from that natural disaster’s public relations debacle much later, namely in the aftermath of the massive triple disaster – earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown – that struck northeastern Japan on March 11, 2011. The majority of the Japanese population had opposed the deployment of service members to Iraq. Yet, it was the State Secrecy Law of December 2013, put into place by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō in the wake of America’s “global war on terror,” that drew the most massive protests as many feared not only restrictions on freedom of speech but an end to civilian control over the military and matters of security. These, together with growing China-Japan territorial and other conflicts, have spurned a rhetoric of “ever more severe” and “ever more complicated” security concerns for Japan. Accordingly, some of the recent public relations projects have shifted to incorporate the language of crisis and urgency and thus appear alarmingly in line with the 2013 State Secrecy Act that empowers the Minister of Defense to designate information he determines to be “especially necessary to be made secret for Japan’s defense” (see http://japanfocus.org/-Lawrence-Repeta/4011).

In addition to these political events, the multi-layered mechanisms of engaging new electronic and digital technologies such as those used in the film furthered the military’s tighter embrace of the aesthetics of the entertainment and media world. Even ten years ago, the defense ministry’s and SDF branch websites looked dull and bureaucratic. Now, they offer video clips and games, individual service members’ accounts of their motivations and experiences, and other dynamic materials in addition to data about capabilities and missions.

The military public relations apparatus is now appealing to a youthful audience that is largely clueless about the circumstances of the Constitution’s Article 9 and the U.S.-Japan alliance. Many in the young generation tend to see the first as outdated and the second as fait accompli and unproblematic.

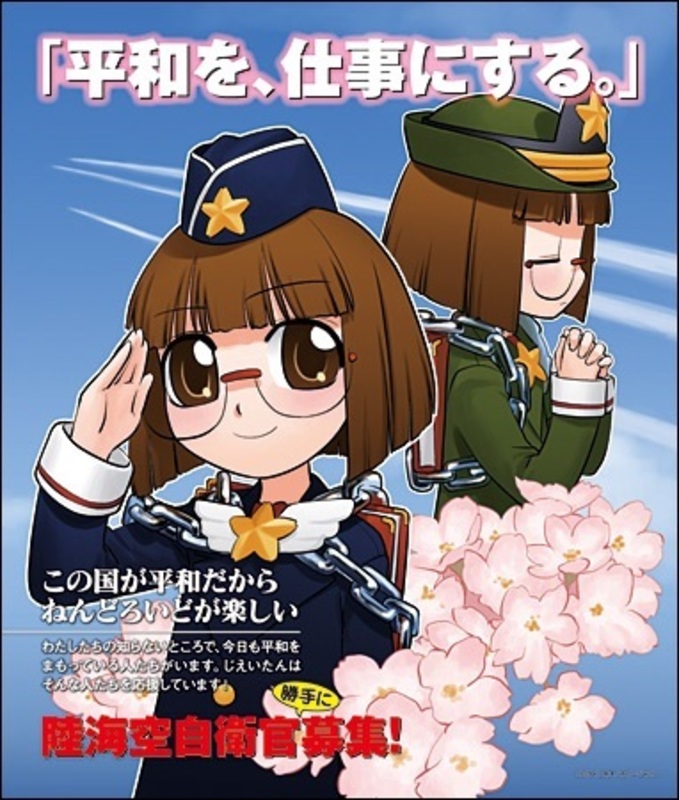

Today, SDF presentations range from professionally shot defense ministry-sponsored interviews with service members to staged encounters of young service members with equally young fellow citizens who appear utterly ignorant of the SDF and matters of defense more generally https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cah5SYGq9U8, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-Wt3Nl-Hvo) to cheerful messages and imagery that defy the vision of the SDF’s future laid out in the National Defense Program Guidelines for FY 2014. They include fast-paced weapons systems flashing across one’s screen. One 2013 highlight was the first publically advertised Mr. and Ms. Maritime Self-Defense Force contest showing each contestant in his fast-paced often high tech work on land, sea and in the air as the beat goes on (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SUEVf6I-NA). Another was the almost seamless merging of military and popular cultural takes of the SDF during open house days of bases across Japan. For instance, while the National Defense Program Guidelines for FY 2014 and Beyond was being worked out, the Ministry of Defense homepage continued to encourage visitors to “Believe your heart” (fig. 1) and promised recruits that once in the SDF, they would come to “love themselves” by virtue of “making peace [their] business” (fig. 2).

Fig. 1: The new Self-Defense Forces public relations line of 2014, “Believe your heart.” Source: GSDF webpage of the Ministry of Defense. The video clip with the same “Believe your heart” rhetoric and aesthetic can be found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-Wt3Nl-HVo (Sakura Channel, 8/12/2014).

Fig. 2: More recruitment material following the 2011 triple disaster in northeastern Japan promises that once in the Self-Defense Forces, a service member would surely “love oneself,” due to the fact that they “make peace their business.”

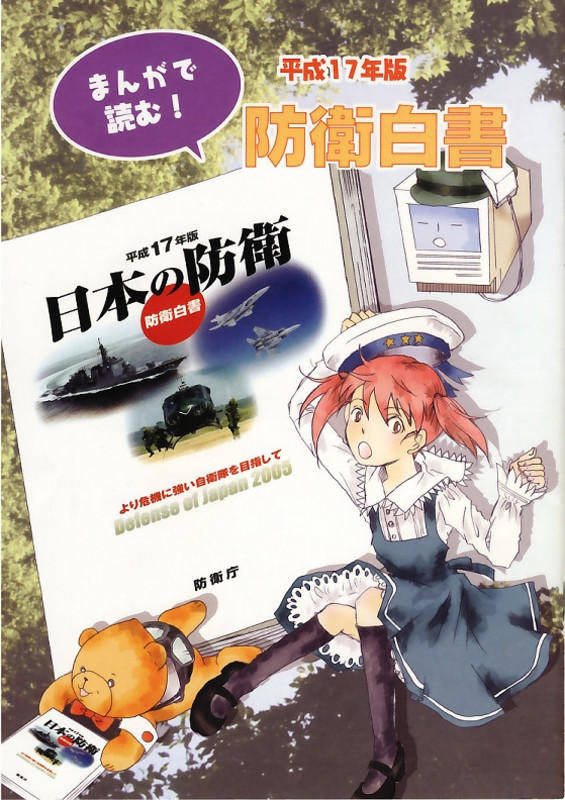

Yet even in the announcement proclaiming the newly dynamic joint SDF, military narratives spread through defense ministry and SDF branch sites remain cleansed of information on potential or actual military missions and the death and destruction that follow in their wake. Instead, they are said to exist “for further contribution to world peace” (http://www.mod.go.jp/e/). Many such textual and visual narratives effortlessly and seamlessly blend with and actively employ an expanding military popular culture whose key characters are gendered female, coded childlike and unapologetically sexualized (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Official 2005 defense white paper.

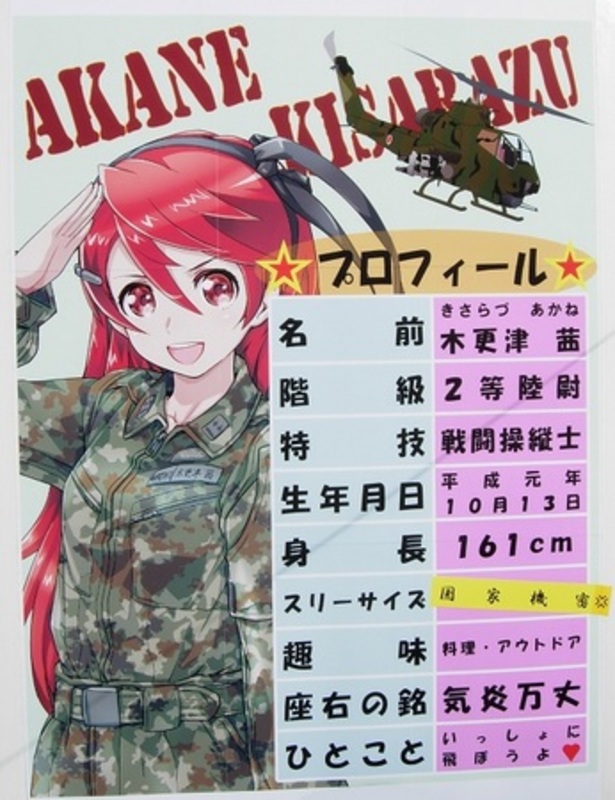

Japan’s 2005 defense white paper as manga, for instance, was enlivened with a Lolita-type girl figure and her loveable bear. Similarly, as part of an air show in Chiba prefecture in October 2012, a colorfully decorated new anti-tank helicopter whose primary capability, let’s not forget, lies in blowing up tanks, and a red-haired female in GSDF uniform by the name of Kisarazu Akane, stole the show (fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Source: http://en.rocketnews24.com/2012/10/19/japans-armed-forces-show-their-playful-side-moe-style-attack-helicopter-wows-crowds/

Mixed messages for sure. And why should they not be so? After all, the SDF engages in a whole range of missions and addresses a great variety of domestic and international audiences. In light of Abe’s nationalist appeals and calls for constitutional revision, China-Japan tensions, and the politics of fear regarding a dynamic and potentially expansive China, some among these audiences will surely end up blindsided.

Sabine Frühstück is Professor of Modern Japanese Cultural Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara and a Japan Focus associate. She is interested in problems of power/knowledge, gender/sexuality, and military/society. She is the author of Uneasy Warriors: Gender, Memory and Popular Culture in the Japanese Army, published in Japanese translation as Fuan na heishitachi and Colonizing Sex: Sexology and Social Control in Modern Japan. She is the coauthor with Anne Walthall of Recreating Japanese Men. http://www.eastasian.ucsb.edu/home/faculty/sabine-fruhstuck/

Related articles

• Fumika Sato, A Camouflaged Military: Japan’s Self-Defense Forces and Globalized Gender Mainstreaming http://japanfocus.org/-Fumika-Sato/3820

• Sabine Frühstück, AMPO in Crisis? US Military’s Manga Offers Upbeat Take on US-Japan Relations http://japanfocus.org/-Sabine-Fruhstuck/3442

• Sabine Frühstück, “To Protect Japan’s Peace We Need Guns and Rockets:” The Military Uses of Popular Culture in Current-day Japan http://japanfocus.org/-Sabine-Fruhstuck/3209

• Tomomi YAMAGUCHI and Norma Field, Gendered Labor Justice and the Law of Peace: Nakajima Michiko and the 15-Woman Lawsuit Opposing Dispatch of Japanese Self-Defense Forces to Iraq http://japanfocus.org/-T-Yamaguchi/2551

• David McNeill, In the Shadow of Hiroshima. U.S. Marines and Japanese SDF collaborate at Iwakuni six decades after the bomb http://japanfocus.org/-David-McNeill/2390