Introduction

At noon on Wednesday, August 4, 2010, the Public Relations Office of the United States Forces Japan (USFJ) released the first of four volumes of a manga, Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership.1 The manga series was intended to mark and celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (better known as AMPO) that had been signed between the United States and Japan in Washington, D.C. on January 19, 1960. Despite its express purpose to burnish the reputation of USFJ and appease critics of the alliance, the launch of this entirely new public relations effort was unfortunately timed. Delayed by several months, it was released two days prior to the 65th anniversary of the dropping of “Little Boy” on August 6, 1945. It also came shortly after the failure to create a new base to replace Futenma Marine Corps Air Station.2 “In this politically and militarily charged environment,” explained Major Neil Fisher, the director of the Public Relations Office and a member of the U.S. Marine Corps, “every element in the manga suddenly meant something.”3 Drafts of the manga had been vetted carefully by a slew of military and other officials beyond the Public Relations Office in Tokyo. Apparently, all senior leadership within USFJ, representatives in the International Public Affairs Office of the Japanese Ministry of Defense, the North America desk of the Pacific Command in Hawai’i, as well as the Pentagon were consulted to weigh in on the final product before it became available on the USFJ webpage for free downloading and promoted in a variety of locales. At the same time, 100,000 copies were produced in hardcopy and distributed to people around U.S. military installations; to people who perhaps had not yet made up their minds about how they felt about the alliance, ranging from mid-teens up to mid-thirties; and to attendees at manga and anime fairs.

While the anniversary might have been an opportunity for a critical reflection on the history of the alliance, an “historical look at a successful and important relationship instead of a political commentary on the current moment” had been desired. Major Fisher described his office’s directives as follows:

We wanted to keep it as light as possible. We are not able to resolve the current political aspects [of the alliance; the author]. I have just been to a dinner reception at the embassy with 100 university students. One student asked, ‘How do Americans feel about the continuous state of war and how do they feel about Japan and its peaceful existence?’ This question paints the full picture. Japan doesn’t know war, doesn’t know conflict. We are trying to explain the relationship between the two militaries. We couldn’t resolve the issue of how to bring up the contentious issues in this manga.

Hence, the manga playfully describes a carefree U.S.-Japan alliance and confirms the role that USFJ have played in this relationship. The Public Relations Office of USFJ settled on a three-chapter model for all four issues. In each issue, the first chapter provides a continuing story line; the second chapter explains the relationship between the U.S. service branch and its Self-Defense Forces (SDF) counterpart; and the third chapter maps military installations and activities. Two characters dominate the narrative. One is Arai Anzu or Ms. Alliance, an ordinary-looking Japanese girl with long dark hair who wears glasses and impersonates Japan. The other is USA-kun, a play on “USA” and “usagi,” the Japanese word for “bunny.” He is a boy visiting from and embodying the United States who wears shorts and a bunny hoodie. The two figures contemplate the role of USFJ and the usefulness of the U.S.-Japan alliance. There are a number of other females who also appear in the manga, but Mr. USA is the only male character, a feature that caused some consternation in the Public Relations Office of USJF as well, according to Major Fisher:

I am trying to figure this out myself. Why so many females? I asked them. I gave them a lot of leeway. Our biggest concern was accuracy and content as long as the characters were not derogatory or risqué. But there is only one guy. In volume two we are going to have more characters. I am learning more and more about manga. The male audience seems to prefer female characters. There is a lot of give and take with the audience. We don’t want this to be an American product. We need to keep our Western sensibilities out of the comic. The Marine Corps issue will have more male characters though.

Major Fisher describes the production of the manga as a learning process, but also as an attempt to speak Japan’s language, both literally and culturally.

(Pop) Cultures of Military Public Relations

Military public relations efforts around the world promote an impressive variety of images of themselves. These include selective, cleansed and aestheticized images of what the military claims it does. Accordingly, such images typically center on the military capacity to project power and use sophisticated technology, for instance, while carefully suppressing its capacity to kill large numbers of people and cause enormous destruction and environmental disasters. Other images underscore what the military promises to provide its members. Those images focus on a portrayal of the military as a platform to mature, show courage, or sacrifice oneself for a national objective, for instance, while thoroughly removing from the picture the military’s preference for recruiting the young and naïve and the possibility that they will return physically and psychologically damaged, or in body bags. Alternatively, military organizations present themselves as a valuable or, at least, a predictable career path. No matter how different, contradictory, and unrealistic these images might be, their core message is designed to make them appear useful and necessary and thus appealing to the audiences of these public relations efforts, be they recruitable youth, worrying parents, or complacent and/or hostile citizens. Military establishments the world over perceive such public relations activities as increasingly necessary for a number of reasons: For instance, military budgets in many parts of the world have exploded rather than decreased since the end of the cold war and, in many people’s eyes, draw important resources away from education, health, and other public services whose budgets have frequently been slashed. The United States, whose military budget is more than half of the entire world’s military budget, is a prime example. At the same time, public interest in and willingness to go to war has decreased in many western democratic societies. For that trend, Japan is an obvious case in point, but so too is much of Western Europe. What is certain is that the public relations officers of the Self-Defense Forces and USFJ agree that Japan is a particularly difficult place to successfully engage in such efforts. According to Major Fisher, the environment is very challenging at headquarters but varies according to locale throughout Japan:

It’s challenging at headquarters because of the various relationships that need to be balanced with MOD, MOFA, and other agencies of the Japanese state […]. The other factor that makes public relations work challenging is the fact that Japan has lived in a peaceful environment for so long that they don’t see the need for a standing military and thus don’t understand the role of the U.S. military in the country. In that sense the situation of the U.S. military is similar to their own Self-Defense Forces, but on top of it, we are foreigners.

It seems obvious then, that USFJ was rather desperate to handle this anniversary year well. Hence, the popular cultural format of a manga seemed particularly suitable to endearing USJF to an audience in Japan that they experience as hostile, critical or ignorant. In Japan, “adult manga” or manga that describe complex matters in a manga booklet, particularly for young people or people with a lack of interest in the subject matter, have been common for decades. At least since the 1980s, large corporations and government agencies, including the Ministry of Defense and the Police, have discovered the educational potential of the popular cultural form. They began to produce instructive manga with appealing main characters. Available also as emblems or stickers, these figures adorn recruitment materials for government agencies and public relations materials for a wide range of corporations and businesses. Produced as three-dimensional figurines in various sizes, they can be attached to cellular phones, bags, and rear window mirrors, or serve as decoration in people’s homes. They serve as mascots designed to foster institutional or corporate identities among employees and positive feelings among the wider citizenry. In a society that is so permeated with the aesthetics of manga and animation, goes the rational, this strategy is de rigueur across different agencies, institutions and corporations no matter what the composition of the targeted clientele.

It is not particularly surprising that a manga was produced to somehow acknowledge the 50th anniversary of the alliance. What is surprising is that it was the USFJ that chose to do so. As Major Fisher noted,

About a year ago our directors at USFJ needed to think about how to address the 50th anniversary of the relationship and the security treaty. They came up with a list of 25 ideas. General Rice reduced the list to three.4 One was the creation of a manga.5 We spent fall and winter researching manga. They are different from US manga. They are often risqué. It was a challenge.

A number of critics have pointed out the tendency of public relations materials to present corporations as benevolent service institutions rather than the capitalist enterprises that they are (Kinsella 2000). Military manga also provide organizations – whose members, after all, train to exercise extreme forms of violence – with the possibility of presenting a cuddly, depoliticized image. In this specific manga, the embodiment of complex configurations such as military establishments or nation states in two children also helps to further the desired “innocent character” of their characters and, by extension, of the institutions they stand for as well as to minimize, dehistoricize and flatten these very configurations.6 In Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, the complexities and magnitude of the so-called “war on terror” shrink and metamorphose into a bunch of cockroaches that need to be exterminated. The frequently and often violently contested alliance appears simply as an important, long-lasting friendship, cleansed of all such trials. The dramatic imbalance of the partners in this alliance is thoroughly suppressed or even reversed. The Asia-Pacific War in which Japan’s defeat created the basis for the alliance remains unspoken.

The following is a critical reading of this first volume against the backdrop of similar kinds of efforts by military establishments.

The Manga: Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership

|

Fig. 1: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, cover. |

Except for the cover page that reads Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership in Japanese and English, the manga is written entirely in Japanese only. Ms. Alliance runs into the picture dragged by Mr. USA. She wears a blue dress, long, dark hair, brown eyes, and glasses. Mr. USA is clad in a bunny-hooded white sweater and blue shorts. There is a golden star on a blue background on the chest of his sweater, perhaps signifying (one of the stars of) the American flag as well as hinting at Superman’s costume. In line with manga conventions, the two children’s eyes are huge, their heads disproportionally large, and their faces and bodies androgynous and very similar to one another. Physically they appear to be of the same size, perhaps signaling the public view of the alliance favored by most U.S. and Japanese officials as equal and balanced, except for one frame in which Ms. Alliance looks down at a much shorter Mr. USA. The two children run above an American flag. A Japanese flag floats in the background and is the same size as the U.S. flag.

|

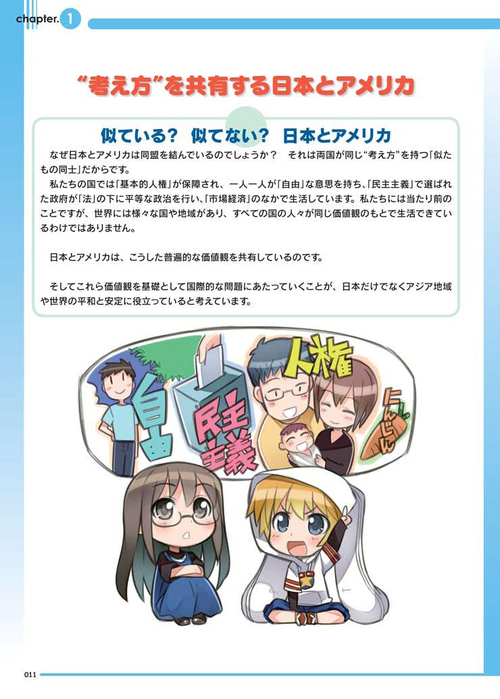

Fig. 2: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 1. |

In short, Mr. USA, a white, blue-eyed, carrot-orange haired American boy, visits the home of Ms. Alliance, his female Japanese friend. She is clueless about military matters. He explains to her the role of the USFJ in Japan. On page 1, the girl stands in a Japanese house entrance and is introduced as Arai Anzu (Ms. Alliance) with the last name written in Chinese characters. USA-kun (Mr. USA), the boy, carries a large backpack and waves at the girl. The manga’s table of contents beneath the image reveals a story in three chapters on the Japan-US alliance (chapter 1), the U.S. Army in Japan (chapter 2), and U.S. Army installations in Japan (chapter 3). The manga artist is Hirai Yukio. Sasakibe Yoshiyuki at Hobby Japan is responsible for the story and the text (more about the artistic and corporate provenance below).

|

Fig. 3: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 2. |

Using characters to represent countries always brings with it the complications of sex, age, and physical type, none of which necessarily relate in an easy way to the countries they are representing. Edward Said (1979) pointed out the Orientalist habit of constructing the Occident as analytically minded male and the East as mysterious, intuitive female; and showed how these constructions played into unequal power relations between East and West. Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership keeps with this convention by representing Japan as female and the USA as male. At the same time, however, it shows awareness of the Orientalist accusation by refraining from painting Mr. USA as a big, powerful male who is protecting a smaller, weaker female Japan. Such a portrayal likely would have struck the Japanese readership as patronizing and would have clashed with the theme of equal partnership, which permeates the manga. As is, the power relations represented are in stark contrast to those represented in World War II propaganda. As John Dower has found, in wartime Japanese propaganda imagery, Japan typically appeared as a young boy vis-à-vis the degenerate old men, USA and UK (US propaganda was more likely to represent Japan as a beast or an ugly bucktoothed and bespectacled soldier). So, Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership keeps with the convention of a gendered representation but breaks with representations of age as a tool to mark difference.

|

Fig. 4: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 3. Fig. 5: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 4. Fig. 6: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 5. |

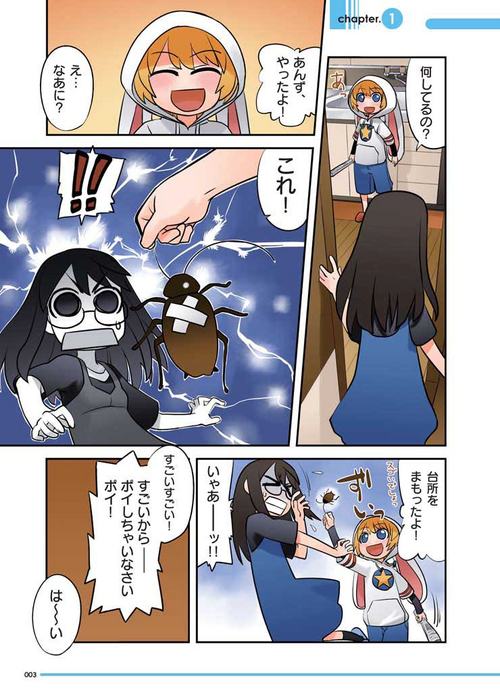

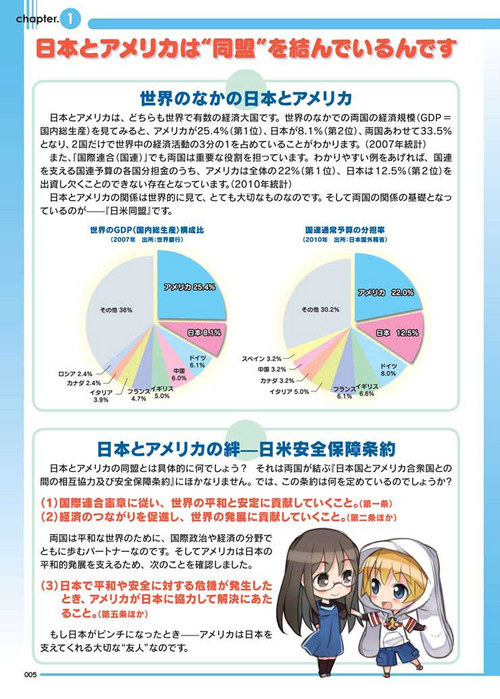

Page 2 continues with an introduction of Mr. USA, who roams Ms. Alliance’s house with what looks like a rolled-up newspaper while Ms. Alliance eats a cookie and watches television. Suddenly she hears a huge noise and Mr. USA announces that he “has done it” (page 3). It turns out that he had found a cockroach in the kitchen and killed it. When he holds it up in front of her face, Ms. Alliance turns away in disgust. Apparently still under the influence of the horrifying sight of the dead cockroach, Ms. Alliance inquires why Mr. USA has come to “protect her house” (page 4). He announces that they share an alliance and thus are “important friends.” Clueless, Ms. Alliance asks, “alliance…?” The answer is provided in the seemingly politically neutral format and tone of matter-of-fact statements, graphs and percentages: Japan and America are bound by an alliance. Japan and America are both economic superpowers. Their total GDP constitutes 33.5% of the world’s GDP, with America holding a share of 25.4% and Japan 8.1%. A multi-colored disk graph shows that the two countries are also the most important contributors to the budget of the UN with a U.S. share of 22% and Japan of 12.5%. The Security Treaty, the basis for the manga and other celebratory activities, is boiled down to three articles: following the UN Charter, both nations contribute to international peace and security; both nations commit to contributions to world economic development; and, if a peace and security crisis emerges in Japan, America assists Japan in finding a solution. Despite the children’s conversation about the 50-year relationship, the narrative is decisively ahistorical. There is no place for the actual history of the treaty. Too hot to handle are the story of its violent renewal in the face of entrenched popular opposition; the story of the basis it has provided for the use of Japan as a launching pad for American troops during various American wars, from Vietnam to Iraq and Afghanistan; and the story of the political, economic and environmental burden military bases pose particularly in Okinawa.

|

Fig. 7: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 6. Fig. 8: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 7.

Fig. 9: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 8. |

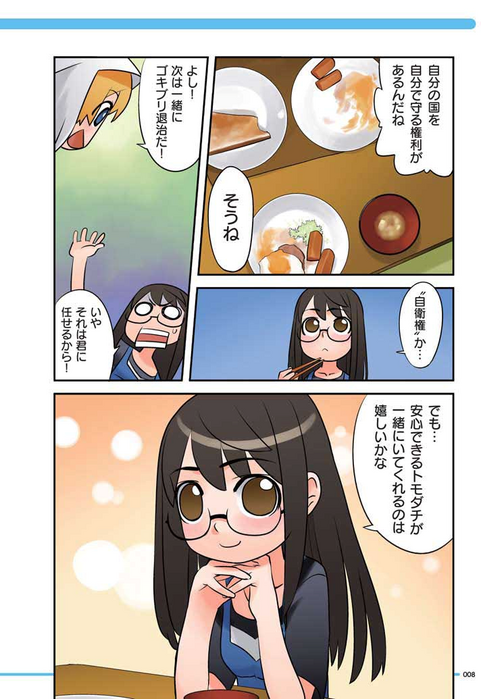

Returning to the conversation of the two children, Ms. Alliance acknowledges she knew only the name, alliance, and suggests that as protector he doesn’t have to work all that hard. Mr. USA, however, points out to her that Japan is not allowed to engage in war, ostensibly to suggest that that would be his/the USFJ’s role. To which she inquires whether he is referring to the “renunciation of war” (quotation marks in original) in the constitution (page 6). The story shifts again to factual information about Article 9 of the constitution and the coexistence of the constitution in conjunction with the “right of self defense” (quotation marks in original), that, in actuality, has remained contested as well (page 7).

As Ms. Alliance contemplates the notion of a country’s right to self-defense, Mr. USA asks her to join him in the extermination of cockroaches. She prefers to leave that to him while she continues to eat breakfast and meditate on the right of self-defense. Here cockroaches stand in for all those that are classified as America’s and, by extension, Japan’s enemies. To Major Fisher, director of the Public Relations Office, the interest in what and whom they might represent comes as a surprise, and their appearance in the manga as one of those accidents many of which he and others have eliminated in draft versions of the manga.

We only saw them [the cockroaches, the author] when it was over. We didn’t think about them. We were only concerned with USA-kun. This is a much more tame character than what we were originally presented. At first USA-kun had a huge hammer to smash the cockroaches. We couldn’t have this go forward. The hammer had to be changed to a newspaper. The cockroach issue never popped up on our radar. I don’t think the artist was going after a particular other…

|

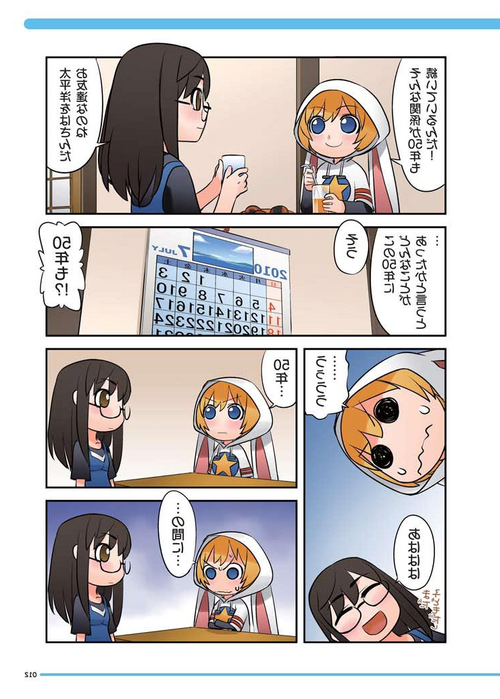

Fig. 10: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 9. Fig. 11: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 10. |

The actual image and symbolism of an oversized hammer in the hand of Mr. USA struck the public relations office as aggressive and detrimental to its implicit attempt to present a smoothly functioning, well-balanced, and harmonious relationship. Hence, it was replaced with the rolled-up newspaper in Mr. USA’s hand, while the cockroaches passed everybody’s scrutiny. Apart from the issue of depicting possible enemies as vermin which is very much in line with US World War II propaganda on Japan (Dower 1995), Ms. Alliance’s fear and disgust towards the cockroach reinforces another stereotype of Japan as a squeamish weakling unable to defend itself as a nation, undoing much of the hard work of maintaining political correctness throughout the manga and making a mockery of USFJ’s claims to “respect Japanese culture.”

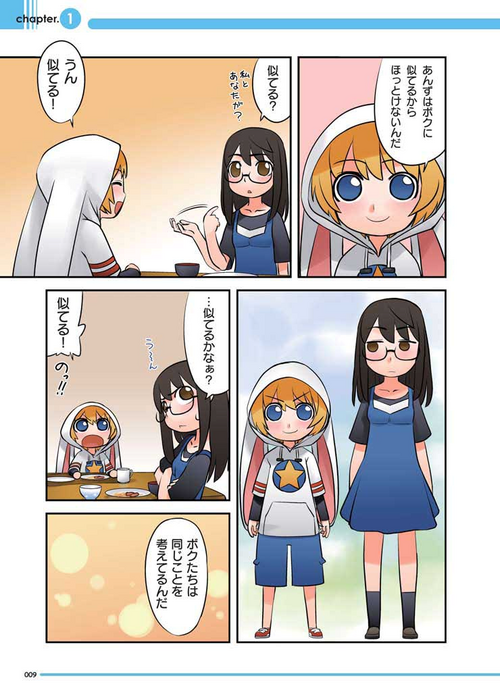

The story proceeds to the deep-seated stereotype of a cultural gulf of essential difference between the United States and Japan (page 9). Out of the blue, Mr. USA announces that Ms. Alliance is similar to him. In a sudden reversal of the power imbalance of the two countries, Ms. Alliance now towers over him with Mr. USA hardly reaching up to her shoulder. Ms. Alliance looks doubtfully down at him. He insists that the two of them think in the same way. He suggests that like him, Ms. Alliance “loves freedom” (a girl walks a dog), “loves people” (a woman and a man hold a baby), and likes to “spend her days smiling” (a white hand is holding hands with another hand of darker skin). Ms. Alliance agrees on all points, and Mr. USA assures her of his protection. “There is one more similarity between the two of us. We both dislike carrots,” says Mr. USA, looking down at both of their plates on which each has left two carrots. Ms. Alliance says that she left them assuming that he liked carrots. This is the only attempt at humor in the entire manga, as Mr. USA, presumably as a joke, calls her a liar (p. 10).

|

Fig. 12: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 11.

Fig. 13: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 12. |

This conversation is followed by a text-heavy instruction again – with Chinese characters for carrots, human rights, democracy and freedom prominently placed at the center of the picture – essentially emphasizing that the two children, and by extension the two countries, share these values. Nothing even hints at the possibilities of why Ms. Alliance actually needs to be convinced of the similarities about which Mr. USA is so adamant. His instruction is successful because it has to overcome only her ignorance, naïveté and doubt, not a difference in her perspective, an awareness of the inequality of the relationship, concerns about the legality of the current alliance, or Japan’s sovereignty as a nation state.

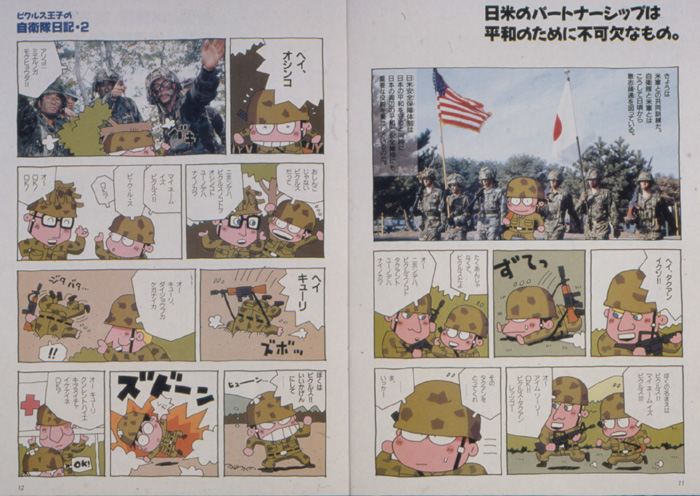

With respect to both, the earnest, enlightening tone and the absence of humor Our Alliance is very similar to another military manga, namely the Self-Defense Forces’ Prince Pickles.7 In that manga, Pickles, a young prince, wanders about in his kingdom and eventually falls in love, marries, and matures, as a result of which he also begins to understand the necessity of armed forces (see figure 15). In contrast to Prince Pickles, however, which achieves some sort of charm and presents a set of likeable characters, it is hard to imagine the reader who would sympathize with the annoyingly passive and disaffected Ms. Alliance, let alone the awkward and patronizing character USA-kun. Given the proof of the artist’s talent which I will briefly discuss below, it seems most likely that, in the interest of political sensibilities, the story was cleansed of any spark (as well as humor, irony or anything else that makes a manga entertaining).

Fig. 15: A page from Kuwahata Hiroshi and Tomonaga Taro’s Prince Pickles’ Self-Defense Forces Diary (Pikkurusu Ōji no Jieitai Nikki II, 1995), p. 11–12. In an interesting contrast to Our Alliance, Prince Pickles depicts differences between Japanese and Americans and the frustrating impossibility of achieving mutual understanding.

|

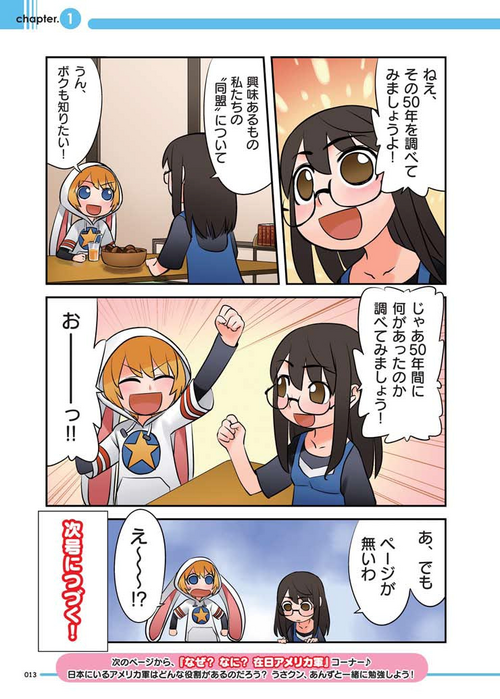

Fig. 14: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 13. |

Continuing the conversation in Our Alliance, Mr. USA tells a surprised Ms. Alliance that their relationship has lasted for 50 years. He fails, however, to come up with anything noteworthy about these 50 years, and for that Ms. Alliance laughs at him. This first chapter of volume 1 ends with the resolution that they would do some research to find out more about the alliance’s 50-year history.

|

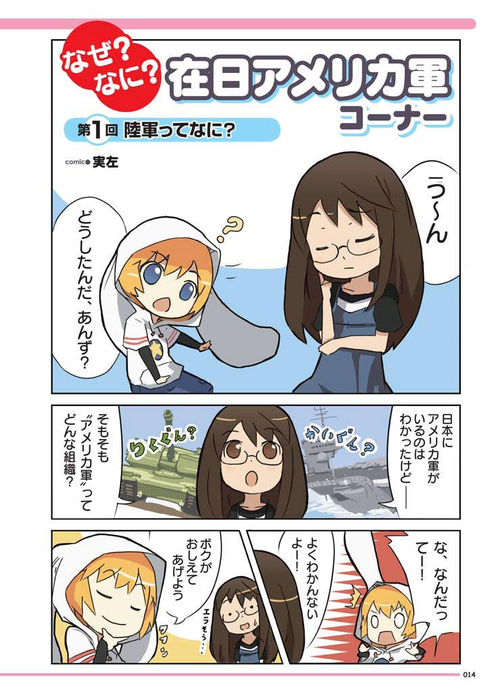

Fig. 18: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 14. Fig. 19: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 15. Fig. 20: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 16. |

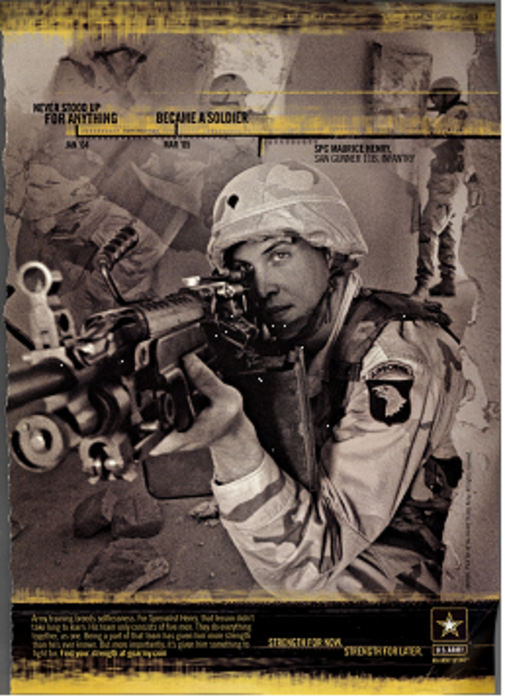

Chapter 2 is titled, “Why? What? U.S. Forces Japan Corner” (page 14). Ms. Alliance knows that the U.S. military is in Japan but admits that she does not really know what kind of organization it is. This issue being devoted to the U.S. Army, Mr. USA explains that the U.S. Army is the biggest branch of service and the branch with the longest history. A few lines about its function (war making) and origins (the Civil War) are followed by a short description of its role in Japan. In a nutshell, it is designed “to contribute to the stability of the Asian region.” Based on the claim that such countries as Korea, the Philippines and Thailand “share the same values,” the manga suggests that the U.S. Army secures the stability of the region on behalf of like-minded peoples. In turn, this stability contributes to the security of Japan (page 18). Halfway through the manga, one encounters the first accoutrements of a military establishment, when a tank for the Army and a war ship for the Navy hint at the tools of “security.” Very much in line with the public relations efforts of the Self-Defense Forces in Japan, but in stark contrast to public relations efforts across military establishments that operate in social environments as dramatically different as the United States and Germany (see fig. 16 and 17), the absence of weaponry from most of the manga makes clear that the USFJ are aware of Japan not being an environment where an emphasis on military power would increase sympathy.

Fig. 16: A typical U.S. Army “influencer ad” from 2007 that connects the potency of weaponry with the maturation of a young man.

Fig. 17: Advertisement stand of the Bundeswehr at the CeBIT 2005.

|

Fig. 21: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 17. Fig. 22: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 18. |

At this point, Ms. Alliance imagines herself in a camouflage uniform, saluting. Photographs of actual soldiers during field training further illustrate the narrative: An African American male is aiming at a target in the invisible distance. Ostensibly watching his back, two Caucasian male soldiers look into the other direction. In this attempt to bring the realism of flesh-and-blood soldiers in action into the otherwise primarily “talkative” manga whose main part takes place in the living room of a middle-class house, the action appears tamed, stilted, controlled and under control. This aesthetic is again in sharp contrast to the typical look of recruitment materials in the U.S. as well as in Japan. On the one hand, recruitment materials for the U.S. Army within the United States tend to evoke the military as a mechanism of (male) maturation, an opportunity for formal education that would otherwise remain unaffordable, or a place of technology-driven suspense. On the other, recruitment materials for the Self-Defense Forces which are designed to appeal to by and large the same audience as that of Our Alliance only rarely hint at the military’s violent potential. As I have shown elsewhere, they do so typically only in the static format of a tank or a combat plane in the background of an image that is otherwise occupied by service members who either also stand still or move in a distinct non-military, leisurely way.

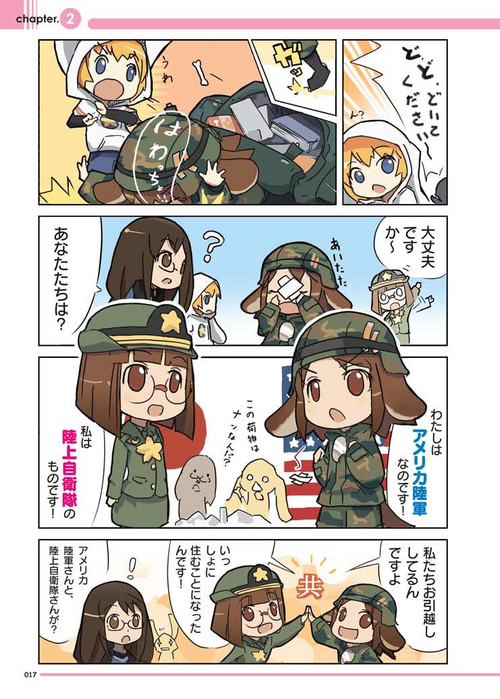

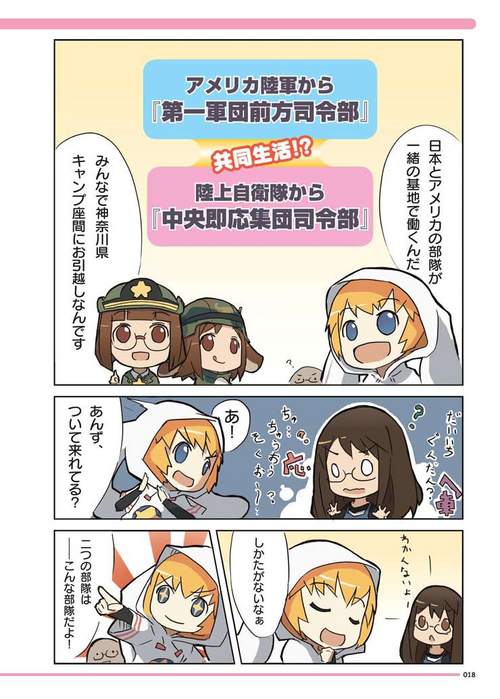

The “intimate collaboration of the Ground Self-Defense Force with the U.S. Army in Japan” is next. Mr. USA marvels at how close the two military establishments are while Ms. Alliance proves to be just as clueless about the SDF as she had been about the USFJ. The manga explains the collaboration concerning “combined exercises,” the “mutual improvement of capabilities,” and the “strengthening of the collaboration.” The manga distinguishes command-level simulation exercises (Yamasakura), which are typically performed electronically, from corps exercises (Orient Shield), which often involve large numbers of troops in the field. Anti-missile defense is another area that is featured as a field of collaboration.

|

Fig. 23: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 19. Fig. 24: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 20. |

Suddenly, two other girls who look almost identical to Ms. Alliance, except for their military uniforms, appear. The first one introduces herself as a service member of the U.S. Army. The other turns out to be a service member of the GSDF. The two exchange “high-fives” in order to acknowledge their collaboration. Mr. USA announces that soldiers from both services work together in one and the same camp. With stereotypical American confidence, the American girl in camouflage announces that even if one is small, one can accomplish all kinds of things (page 19). Ms. Alliance looks puzzled but it remains unclear whether she is unfamiliar with the gesture, confused by the situation, or surprised by the gender of the soldier in camouflage.8

|

Fig. 25: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 21. Fig. 26: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 22.

Fig. 27: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, p. 23. Fig. 28: Watashitachi no dōmei – Eizokuteki pātonāshippu/Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership, back cover. |

The rest of the page features I Corps Forward Headquarters of the U.S. Army in Japan, which was activated in Camp Zama, Kanagawa prefecture, as recently as 2007. During peacetime, the headquarters is only a small organization but its mission and function are flexible and can be greatly expanded. The missions include coordination with the deployed reinforcing units during contingencies, operations support, intelligence to the Self-Defense Forces, deployment as needed, and exercises and/or operations with the Self-Defense Forces or military establishments of other East Asian countries. Most significantly, the corps has been providing combat support and combat service support in the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is also involved in military operations related to homeland security and support of federal, state and local agencies since September 14, 2001, under the name Operation Noble Eagle. Small soldier and helicopter icons illustrate an emergency response airlifting operation. A photograph of actual American soldiers features them in camouflage uniforms and in formation.

A description of the GSDF follows. A girl who looks just like Ms. Alliance (albeit with glasses) establishes that the GSDF also engages in a number of missions in crisis situations. Two actual photographs of GSDF service members in action illustrate technical descriptions of special units and equipment: a unit descends from a helicopter; another rescues Japanese civilians from somewhere abroad (page 20). At the end, Ms. Alliance announces that when the need arises, the Japanese and American branches merge: “That is because it is easier to help each other together.” This collaboration, the two uniformed girls agree, allows them to be “more efficient and to be even closer.” Finally, Ms. Alliance claims to understand the work of the Army. USFJ installations in Japan and particularly Okinawa are described briefly at the very end. The back cover of the manga features an image of two shaking hands.

The Company: Hobby Japan

In an attempt to “keep American culture out of the manga and make it a truly Japanese manga,” Hirai Yukio and the company Hobby Japan were hired to produce it. The choice of artist and company was the result of a competitive bidding process among five companies. Major Fisher remembers the criteria for the selection of Hobby Japan:

Hobby Japan’s proposals were the closest match to what we were looking for. They are in online political military manga. They have a history of explaining military matters online. We wanted to work with a company that had a profile in the field of military and political online reporting and entertainment.

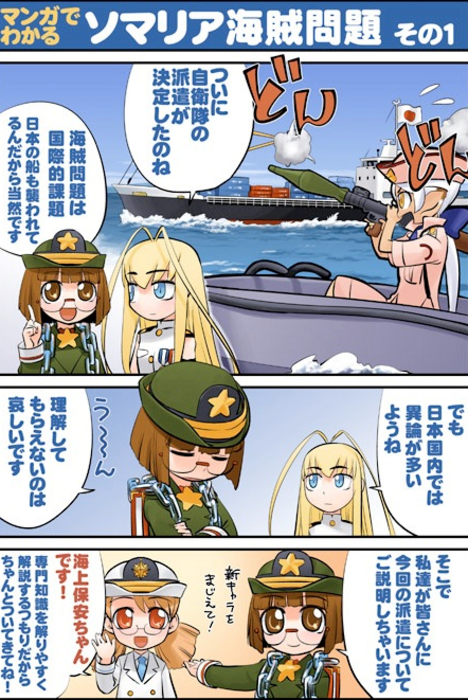

One such example was the pirate attack off the coast of Somalia that prompted the emergency dispatch of two MSDF destroyers to escort commercial ships in the area in 2009.9 Understanding Through Manga: The Somalia Pirate Problem (Manga de wakaru: Somaria kaizoku Mondai) features the female figure Jiei-tan discussing what was then a controversial mission of the Self-Defense Forces to Somalia (see fig. 29). Jiei-tan explains that the Self-Defense Forces were deployed because piracy is an international issue. A female fantasy figure points out that a lot of objections were raised in Japan. Jiei-tan expresses sadness over what she sees as a lack of understanding. But then she perks up and says that this time the Self-Defense Forces, together with the Coast Guard, depicted as another female figure in a white uniform, will do a better job of explaining the deployment. Hobby Japan indeed does have a distinct profile and a 40-year history of its own. One of the company’s fields of core expertise is the production and marketing of war games, be it in the form of manga, animation, video games, or toys. As CEO Yamaguchi Hideo cheerfully explains on the company website,

Hobby Japan has been always opening up the domestic hobby market and offering a new genre as a market pioneer: handmade miniature cars, hobby news magazines, imported plastic models, simulation and war games, RPG, trading card games and so on.10

Some highlights of the company’s innovations include the introduction of adventure games to Japan (1973), the publication of such magazines as Monthly Tactics (since 1981) and Monthly Arms Magazine (1987), the Japanese edition of the tabletop Dungeons and Dragons (2003), Game Japan (2006), the launch of a light novels series HJ Bunko (2006), and the animation broadcasting of Queensblade (2009).

Fig. 29: A page from Understanding Through Manga: Mari-tan [and the] Pirate Problem

(Manga de wakaru: Mari-tan kaizoku Mondai).

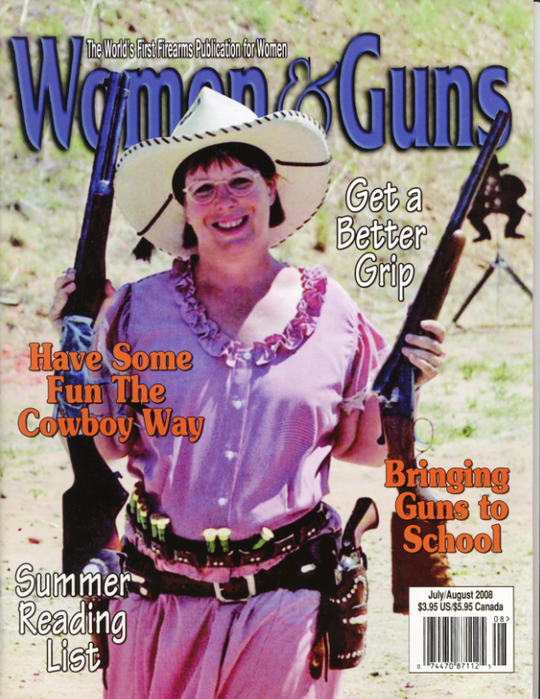

Fig. 30: Cover of Women & Guns, a monthly publication of the Second Amendment Foundation which seeks to secure “the right of the people to keep and bear arms” accessed October 25, 2010).

Similar to paramilitary magazines elsewhere (see fig. 30), the monthly Arms Magazine is typically adorned with young females while its contents explicitly appeal to boys, as follows:

Boys once at least played with toy guns.11 Following that idea the toy gun & military information magazine Arms Magazine was born. It aims to convey the charm of guns as an entertainment. We want to be closer to many more people by offering a wide range of articles, not only toy guns but also real guns, the Self-Defense Force reports and even the trendy military fashion. In short, Hobby Japan engages in publishing, character development, copyright management, hobby goods, planning and distribution, running a hobby news website, import and distribution of foreign hobby goods, retail of hobby goods12 (see fig. 31 and 32).

Fig. 31: Image composite of Hobby Japan products that are advertised on the company website.

Fig. 32: Image composite of Hobby Japan products that are advertised on the company website.

The Artist: Hirai Yukio

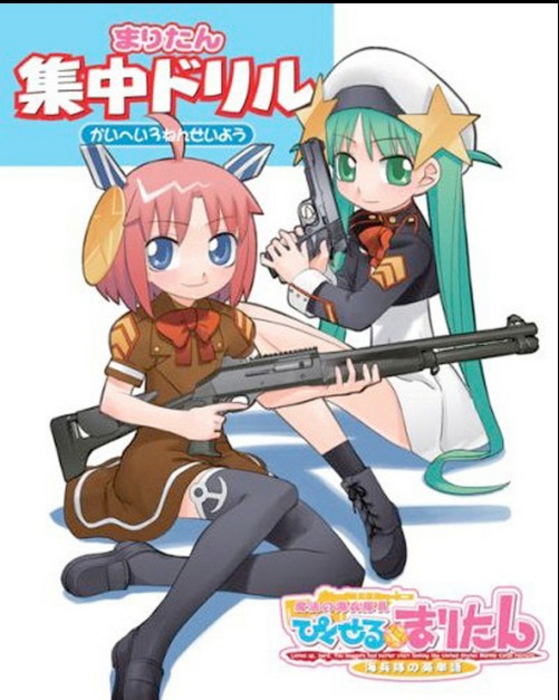

Just like the company Hobby Japan, the manga artist Hirai Yukio also has a name in the mili-tainment and mili-moe field. Perhaps best known in the mili-moe otaku community is his manga, Mahō no Kaiheitai Pixel☆Maritan (Magical Marine Pixel*Mari-tan) that is published in Arms Magazine and simultaneously aired on the Hobby Channel. Magical Marine Pixel*Mari-tan features Sergeant Mari-tan, a drill instructor of the U.S. Marines (hence, Mari-tan as in Marines; –tan is a diminutive of –chan), who trains new recruit Army-tan under the supervision of Lieutenant Commander Navy-tan. There is also a Jiei-tan from Jieitai or Self-Defense Forces whose most notable trait is a heavy book chained to her shoulders, representing Article 9 of the constitution. Mari-tan is clad in a Marines uniform but wears hot pink hair as any manga figure might. She is introduced as a princess of the Magical Kingdom of Par(r)is Island, a name that might be understood as a reference to Paris in France or the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in South Carolina. The Magical Kingdom has signed a treaty of cooperation and friendship with the United States. The appearance of a “princess” from a “magical kingdom” seems reminiscent of the three volumes of the SDF’s Prince Pickles manga: Just like Prince Pickles, Sergeant Mari-tan and her fellow characters appear in a conventional cuddly shape with big heads and small bodies. Like Prince Pickles and most other manga produced in Japan, Mari-tan and her fellow characters have big round eyes. Both are marketed as applications on a number of consumer goods. They are also available as PVC figurines for otaku of mili-moe objects.13 Jiei-tan, for instance, can be purchased as a PVC figurine clad in a GSDF uniform, wearing glasses, and glued onto a cherry-blossom shaped pink pedestal. But the similarities to the military fantasy world of Prince Pickles or the other kind of fantasy world of Sailor Moon and other flying girls stop right there. Quite in contrast to Prince Pickles, his girlfriend Paseri-chan and others in the Self-Defense Forces’ manga, Mari-tan is primarily out and about harassing new recruit Army-tan and the occasionally appearing Jiei-tan.

Furthermore, Mari-tan is not advertised as an endearing embodiment of the Marines, but rather marketed as a figure (and manga) whose ostensible intent is to teach curious Japanese readers how to swear like a U.S. Marine, borrowing language from the very first drill sequence in Stanley Kubrik’s Full Metal Jacket (1987).14 “It’s fucking English time!” reads the cover text of one book. Readers can learn phrases such as, “Your puny little ass is mine!” and “To show our appreciation for so much power, Marines keep heaven packed with fresh souls!” Mari-tan’s origin story is a parody of so-called “magical girl” (mahō shojo) shows, in which the heroine visits Earth from some fairy realm on a mission of good (e.g., Sailor Moon). She also represents, however, a mockery of the military, an interpretation that is further underlined by the fact that in the animated version Mari-tan speaks in a distinct female, high-pitched voice common for females in the medium. Overall arranged in a manner similar to how a conventional language textbook might combine exercises and explanations for pronunciation, use, and sample sentences, one such “English lesson” features Mari-tan holding up a sign that says, “FUCK! Is the basis” (see fig. 33). “Let’s speak: Let’s try to read this in a loud voice: I like you. Come over to my house and fuck my sister!” is followed by the translation in Japanese and with all English rendered in hiragana. A bubble on “Word check!” provides the meaning of the word in Japanese as a verb and a noun. “Point!” encourages the use of the word in various contexts with phonetic spelling. At least when viewed next to the more recent work of the artist for USFJ, it almost seems as if Hirai had played a prank on them.

Fig. 33: Both images are from Magical Marine Pixel Mari-tan Concentration Drills (Mari-tan Shūchū Doriru), which was released in 2009; available here, accessed October 28, 2010. 15

Apparently popular among members of the Marines, the manga’s website contains links to all USFJ’s branches. Unsurprisingly, the USJF leadership does not condone the manga. Accordingly, Major Fisher frowns when I mention the manga during our conversation:

We made sure to not have any of the characters of that Maritan manga in ours. We own our product but we cannot control the company’s activities.

Concluding Remarks

Measuring the success of any public relations effort is difficult. Major Fisher does so by comparing the number of hits on the USFJ homepage. He is relatively happy with the response to Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership:

I believe the manga has worked out pretty well. We got some feedback about it being just propaganda but we did not receive any harsh criticism. I am pretty cynical but we got very little negative response. The Japanese tend to be more honest among themselves, mostly for reasons of politeness, and so we heard that the company got a bit more flak. We measure the success of the manga based on the number of hits we get on our website. Before the manga was posted, we got about 900 hits per day. Since the manga has become available we get about 100,000 a day. Our biggest test of its success will be the Marine Corps issue because of their association with the most contentious issues.

The increase of the hit-rate at the USFJ website does not, of course, answer other questions, such as who is reading the manga and how sophisticated their reading might be. 2-Channeru, which with 10 million users is one of the world’s largest Internet fora, provides some hints.16 One poster writing in Japanese asks whether the cockroaches in Ms. Alliance’s/Japan’s kitchen are “Korean or Chinese.” Another calls it “propaganda.” And yet another expresses her/his discomfort at the claim that “Japanese and Americans are similar.” Posters writing in English are less polite, calling the manga “Aryan propaganda shit” and worse, or suggesting that “the boy ‘lives off’ the girl (effectively making him a waste of space freeloader) and in return, only squishes a cockroach? Yeah, that about sums up America’s contributions to the world, stealing the best of our crap and attacking less powerful nations.”17 While the hostile tone is typical for 2-Channeru discussions, which are anonymous, they invite doubts about whether the manga actually achieves its main twin goal, to create a more sympathetic attitude towards USFJ and to solidify the alliance as the best solution to potential security issues in Japan and East Asia.

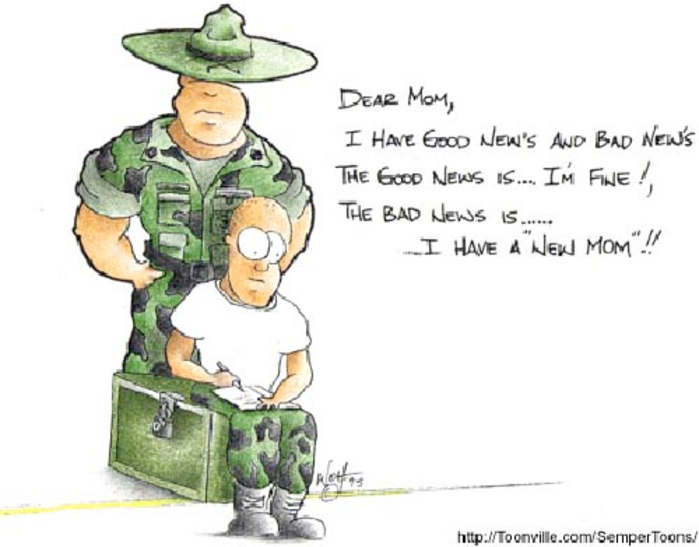

Beyond the question of the success of the manga within the parameters of the Public Relations Office, however, it is important to keep in mind that military organizations the world over put substantial effort into presenting certain fabricated images of themselves to their various audiences. They condense the everyday unheroic boredom off most service members with much of military life to the adrenaline-driven moment of high-speed aircraft; they present the military as a social apparatus whose main goal is to make men of children; they assure parents that the careers they offer are predictable and safe bets for their sons and daughters; some try to be humorous. On the homepage of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in South Carolina, for instance, a cartoon features a physically huge Marine hovering over a young recruit who writes to his mother (see fig. 34) mocking the immaturity of the recruit as well as the ambiguous role of the drill sergeant.

Fig. 34: “Dear mom, I have good news and bad news. The good news is … I’m fine! The bad news is … I have a new mom!!” (source).

Similar to Our Alliance, such public relations efforts cautiously avoid the uglier sides of the military and the effects of its violent culture and charge. And, perhaps more aggressively than public relations efforts elsewhere, the USFJ’s manga, Our Alliance (and the Self-Defense Forces’ Prince Pickles) highlight and illustrate the infantilizing character of military public relations materials. The choice of two children as representatives of two of the most powerful nation states in the world further infantilizes these nations and their capabilities while also underestimating the experience and intelligence of their populace.

In terms of addressing the tensions between the two militaries, and a Japan that is divided concerning the continued presence of the US military in the country, Our Alliance is a lost opportunity and as such in line with the political developments that it so vehemently refuses to directly address. As Gavan McCormack (2010) so aptly put it with regards to the most contentious issue, the future of Futenma, today “there is less sign than ever of this “world’s most dangerous base” … being returned or liquidated any time soon, or a new base being constructed at Henoko.”

This essay greatly benefited from invaluable comments by Ian Condry, Tom Gill and Mark Selden.

Recommended citation: Sabine Frühstück, “AMPO in Crisis? US Military’s Manga Offers Upbeat Take on US-Japan Relations,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 45-3-10, November 8, 2010.

Bibliography

Condry, Ian. “Love Revolution: Anime, Masculinity, and the Future.” In Recreating Japanese Men, ed. Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, Berkeley: University of California Press (in press).

Dower, John. 1995. Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays. New Press.

Frühstück, Sabine. Uneasy Warriors: Gender, Memory and Popular Culture in the Japanese Army. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

—–. ‘In Order to Maintain Peace We Need Guns and Rockets’: The Military Uses of Popular Culture in Current-Day Japan.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, August 24, 2009.

—–. “The Modern Girl as Militarist: Female Soldiers In and Beyond Japan’s Self-Defense Forces.” In Modern Girls On the Go: Gender, Mobility, and Labor in Japan, ed. Alisa Freedman, Christine Yano and Laura Miller (under review).

Kinsella, Sharon. Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. London: Routledge, 2000.

McCormack, Gavan. “Ampo’s Troubled 50th: Hatoyama’s Abortive Rebellion, Okinawa’s Mounting Resistance and the US-Japan Relationship (Part 1).” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, May 31, 2010.

McCormack, Gavan. “The US-Japan ‘Alliance’, Okinawa, and Three Looming Elections,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, September 13, 2010.

Oe Kenzaburo. “Hiroshima and the Art of Outrage.” The New York Times, Friday, August 6, 2010, p. A19.

Penney, Matthew. “War and Japan: The Non-Fiction Manga of Mizuki Shigeru.” The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, September 21, 2008.

Said, Edward. 1979. Orientalism. Vintage Books.

Sato Harumi and Hiroshi Kazusa. “Manga CVN 73: USS George Washington,” accessed October 10, 2010.

Tanaka Yuki. “War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The Humanism of His Epic Manga.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, September 20, 2010.

Terashima Jitsuro. “The Will and Imagination to Return to Common Sense: Toward a Restructuring of the US-Japan Alliance.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, March 15, 2010.

Endnotes

1 BBC was the first to write about the manga. CNN followed suit with a short article by Matt Alt, who runs a Tokyo-based entertainment localization company that specializes in video games, comic books and other pop culture. Steve Clemons’s The Washington Note of August 5, 2011, 7:55am, also briefly took up Alt’s article. Under the title, “The U.S.-Japan strategic alliance… manga style,” Alt writes the following: “For years, foreigners have tittered over the Japan Self-Defense Forces’ cuddly mascot character, Prince Pickles. But now the United States military has upped the ante by producing an entire manga-style comic book celebrating the strategic relationship between the two nations. Could this be the beginning of a new era of ‘mutually assured cuteness?’” See also Kyung Lah’s report for CNN here.

2 Gavan McCormack has dissected the history of that conflict in a series of essays, “Ampo’s Troubled 50th,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, May 2010. Ōe Kenzaburō, Terashima Jitsurō and others also have participated in this recent debate. See, for instance, this link. Gavan McCormack in the Asia Pacific Journal.

3 All quotations of Major Neil Fisher are from an interview with the author, September 10, 2010; the interview was set up by Donald E. Preston, MSgt. USMC, Media Liaison Chief, Headquarters U.S. Forces, Japan (J021), Yokota.

4 Lieutenant General Edward A. Rice is the commanding officer of USFJ. He is also commander of the 5th Air Force, Yokota Air Base. For biographical details see this link.

5 The idea of the manga is not entirely new for USFJ. About three years ago, the U.S. Navy produced a manga about the role of the USS George Washington, an American nuclear-powered supercarrier that can accommodate approximately 80 aircraft. On December 1, 2005, the U.S. Navy announced that USS George Washington would replace USS Kitty Hawk as the forward-deployed carrier at Yokosuka Naval Base in Yokosuka, becoming the first nuclear-powered surface warship permanently stationed outside the continental U.S. In an attempt to explain the carrier’s mission to the Japanese public, the U.S. Navy printed a manga about life aboard GW, titled “CVN-73.” According to Major Fisher, that manga was designed purely to shed light on the aircraft carrier (link). The manga can be downloaded from here).

6 The “flattening” of contemporary culture in Japan has been remarked upon by a number of Japan’s most prominent public figures, including pop artist Murakami Takashi and philosopher Azuma Hiroki. However, most of these critics are not interested in or fail to address the political dimension of such flattening and dehistoricizing, which is evident in the circumstances of the production and dissemination of Our Alliance – A Lasting Partnership.

7 For a detailed analysis of Prince Pickles Diary and other volumes of that manga, see Sabine Frühstück, “’To Protect Japan’s Peace We Need Guns and Rockets:’ The Military Uses of Popular Culture in Current-Day Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 34-2-09, August 24, 2009.

8 While females comprise about 20% of the US armed forces, female service members in the Self-Defense Forces have remained less than 5% since the mid-1990s.

9 A controversy ensued over the dispatch of the MSDF ships and led to the Japanese Diet’s Lower House passing an antipiracy bill on April 23. Until the bill became law in June 2009, MSDF ships acted under the maritime police-action provision of the Self-Defense Forces law. Hence, the destroyers would not have been able to protect vessels under attack unless they are Japanese or are carrying Japanese crew members (see Jun Hongo, “MSDF’s Hands Tied on Antipiracy Tour: Operations to Be Limited Until New Bill Passes,” The Japan Times, January 29, 2009). On the basis of the Anti-Piracy Law, the Self-Defense Forces are allowed to escort foreign ships and fire at pirate boats if they ignore warning signals and approach merchant ships. Then-Prime Minister Aso insisted that prior approval by the Diet before a Self-Defense Forces dispatch is unnecessary on the grounds that the use of weapons against pirates, who are criminals, does not constitute a military action as prohibited by the constitution. Such antipiracy missions, however, remain politically and constitutionally sensitive (see “Editorial: Anti-piracy Law,” The Japan Times, June 23, 2009).

10 For more details on the company, see this link.

11 For an analysis of the combined sexualization and militarization of females, see Sabine Frühstück, “The Modern Girl as Militarist: Female Soldiers In and Beyond Japan’s Self-Defense Forces,” paper presented at a conference on Modern Girls on the Go: Gender, Labor and Mobility in Japan, Eugene, Oregon, January 2010.

12 All images are available on the Hobby Japan website, accessed in August 2010.

13 Jiei-tan belongs to the Nendoroid series and can be purchased for about US$40.00. About 100 mm tall, she was released in March 2010, as Nendoroid No.96b Jiei-tan.

14 Parts of the manga are available here.

15 Link.

16 Link.

17 See, for instance, this link.