Migrant-support NGOs and the Challenge to the Discourse on Foreign Criminality in Japan

Ryoko YAMAMOTO

Abstract

Migrant-support activists have comprised a major voice to contest the state-endorsed narrative that presents migrants as a crime threat to Japanese society. This paper investigates the discursive and organizational construction of their challenge against this discourse. It argues that the autonomy and expertise of migrant-support NGOs enable them to challenge the state and create the basis for their modest yet significant political impact.

Introduction

In migrant-receiving countries, immigration control is increasingly discussed in the language of crime control. The discourse that associates foreignness and criminality is particularly evident in Japan because of a recent history of low immigration and the widely-held belief that Japan is ethnically homogenous.

This paper examines how migrant-support non-governmental organizations (NGOs) challenge this prominent discourse. Migrant-support NGOs, largely consisting of Japanese nationals, have confronted the Japanese government on behalf of migrants’ rights since the late 1980s ? Based on ethnographic research conducted in Japan in 2004 and 2005, this paper argues that their autonomy from the state, expertise in immigration practice, and civic activism make migrant-support activists a capable actor in immigration politics in Japan. Despite their limited organizational resource, migrant-support activists participate in domestic and international politics as independent experts of Japan’s immigration practice. Their political impact is significant as a locus for an oppositional voice and an informed watchdog.

The focal point of my fieldwork observation was an umbrella organization called Ijurodosha to Rentai suru Zenkoku Nettowaku, or Ijuren, Migrant Workers Network. Founded in 1997, Ijuren encompasses approximately 90 migrant-support organizations throughout Japan. During my fieldwork, I participated in their meetings, interviewed activists, and reviewed their publications. All names of interviewees mentioned in this article (referred to as Ms. or Mr.) are pseudonyms.

At the turn of the century, Japan faced the collapse of two myths that it had embraced for decades: the myth of homogeneity and the myth of public safety. A new influx of migrants in the 1980s substantially increased the number and diversity of foreign-national residents in Japan, making multi-ethnicity in Japan more visible. Around the same time, the image of Japan as a safe country also was challenged. Public concerns about crime increased as the crime rate almost doubled and the clearance rate (more commonly referred as the “arrest rate”) dropped from 60% to 23% between 1983 and 2003.

The discourse of foreign criminality emerged from this convergence. It conflates foreignness with criminal dispositions and presents crime control as a central issue in immigration policies. Generated by the National Police Agency and amplified by politicians and the media, the discourse of foreign criminality claims that migrants, especially those who do not have proper documentation, are a major threat to public safety in Japan.

The conflation of immigration-control and crime-control is vividly observed in the 2003 Joint Statement issued by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, the Metropolitan Police Department, the Japanese Ministry of Justice and the Tokyo Immigration Control Bureau. The statement says, “Many illegal residents are engaged in illegal employment. Furthermore, not a small number of them are engaged in crime to get easy money …for national security, the problem of these illegal residents requires immediate attention.”[1]. The statement declared that Ministry agents would reduce the number of unauthorized residents in Tokyo by fifty percent in five years in order to counter a crime problem in the metropolis. In their framing of immigration control, what is at stake is public safety in the country, and migrants are a dangerous threat to this precious national asset.

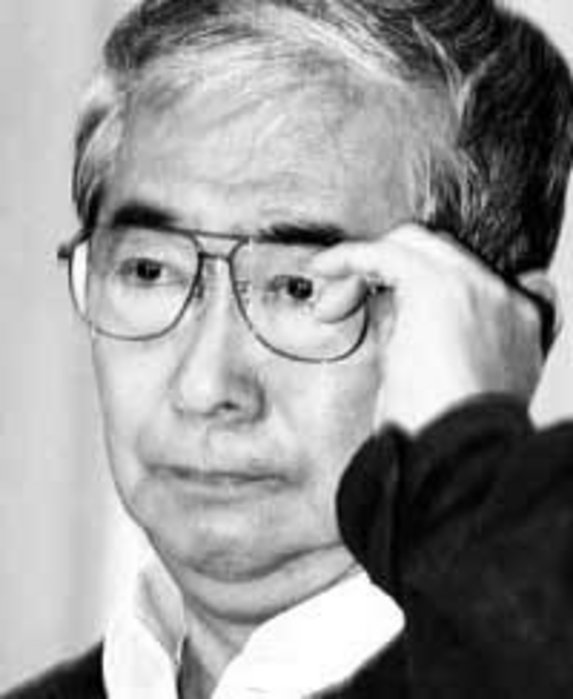

The discourse of foreign criminality links migrants and crime at multiple levels. One common form of association is through statistical presentations [2]. The Police White Papers repeatedly assert the increasing criminal threat of migrants through their statistical report of migrant-perpetrated crimes [3]. Their statistical analyses, however, are typically limited to comparisons within foreigner-perpetrated crimes; comparison of the number of foreigner-perpetrated crimes between different time periods and comparison between different nationalities, for instance. This microscopic analysis obscures the fact that foreign-national offenders have always comprised only a small proportion of penal-code offenders in Japan (See Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: Proportion of Rainichi Penal-Code Offenders among Total Penal-Code Offenders

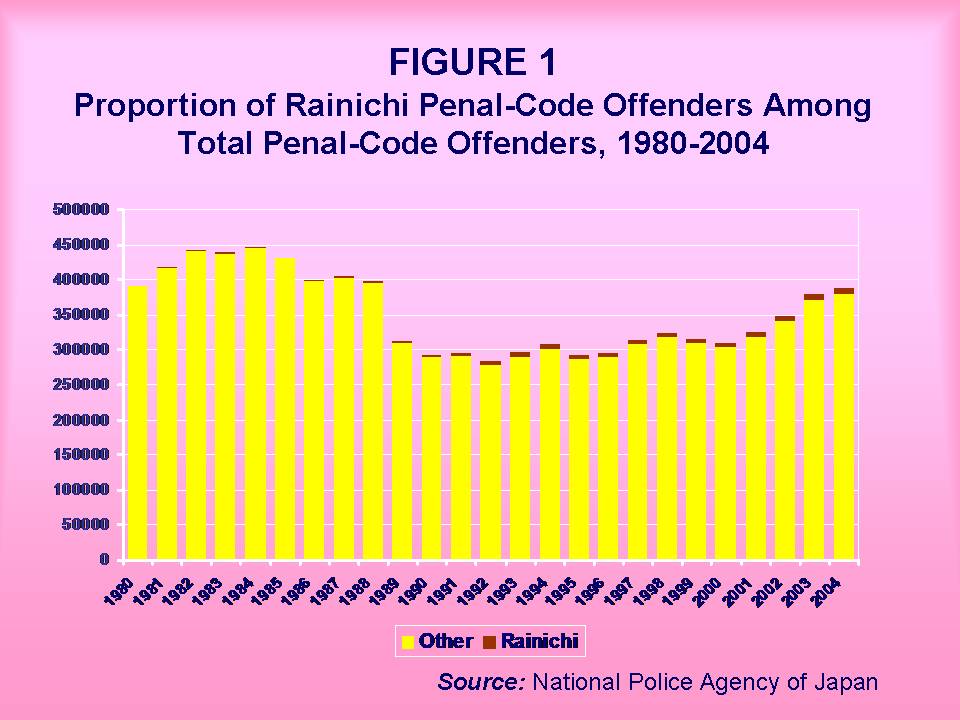

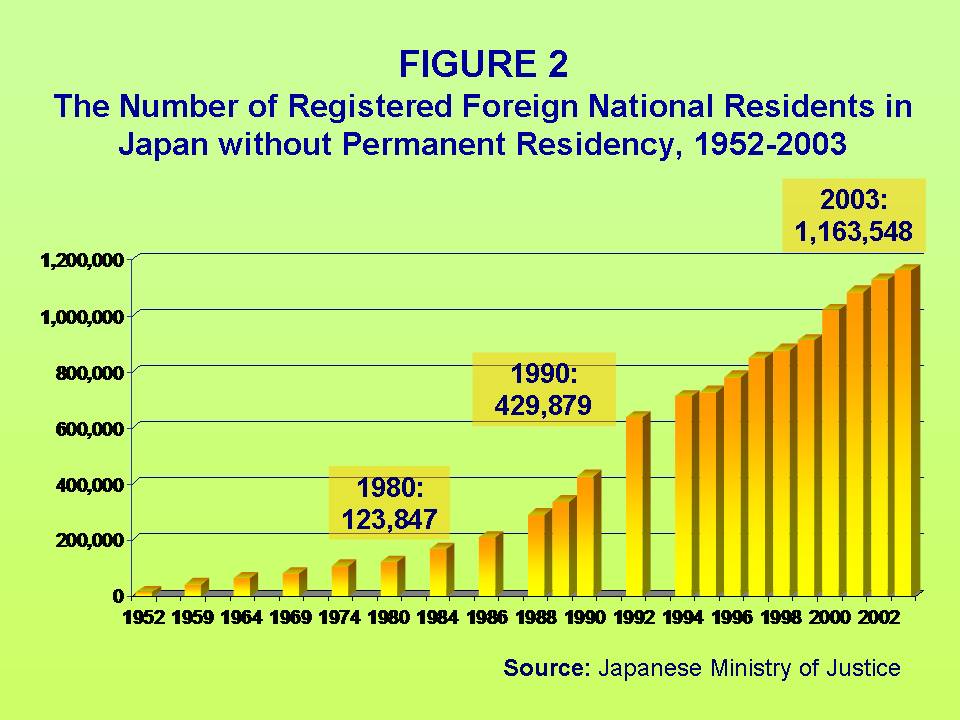

Furthermore, the growth of the number of foreign offenders is largely a product of the sharp increase of foreign visitors and residents (See Figure 2), and after the 1990s, the number of offenders remained relatively flat (See Figure 3). The continued increase of the number of offenses indicates three possibilities: the emergence of professional offenders who commit a larger number of offenses per person, the increased persistence of the police in pursuing additional offenses of foreign suspects, or a combination of both. A closer look at the statistics suggests that the picture is more complicated than a simple increase of the foreign menace.

INSERT FIGURE 2: The Number of Registered Foreign National Residents without Permanent Residency in Japan, 1952-2003

INSERT FIGURE 3: Trend of Rainichi Penal-Code Offenses and Penal-code Suspects, 1980-2004

Another form of foreigner-crime linkage is a portrayal of migrants as the cultural other with a crime-prone character. The 2003 Police White Paper quotes a Chinese inmate who reportedly said, “They say that Japanese prisons are clean and inmates can watch TV. It is easier than life in China” . A description like this equates poverty with insensitivity to punishment, and reasons that Japan’s penal system is too lenient for migrants who are accustomed to a lower living standard. Through these linkages, migrants are collectively constructed as a reserve army of criminals who require, and deserve, strict surveillance and selective control.

The allegation of criminal harm caused by migrants is further dramatized by politicians who are eager to advertise themselves as protective leaders. Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintaro stated “More and more dangerous drugs were spread by the very hands of the ‘sangokujin’ or foreign nationals in Japan. It is your kids who are spoiled [by them]. How could I ignore them?”[4], when he defended his infamous sangokujin statement [5].

The discourse of foreign criminality dichotomizes society into potential criminals and victims along national lines; foreigners are portrayed as potential offenders who need to be controlled, while the Japanese public is depicted as potential victims who need to be protected. Between foreign offenders and Japanese victims, the Japanese state positions itself as the guardian of the latter. In one fell swoop, the foreign criminality discourse foreignizes crime and nationalizes public safety, subsequently constructing immigration control as a security measure to protect good Japanese people from malicious foreign predators.

Discourse of human security: Crime policy as a human rights problem

Migrant-support NGOs paint an entirely different picture of the connection between migration and security. They argue that the real problem the country faces is not crimes by foreigners, but, rather, the xenophobia of the Japanese government, political leaders, and the media.

Similar to the National Police Agency, Ijuren and their affiliates use crime statistics to make their case. However, instead of looking at the growth of foreigner-perpetrated crimes, they emphasize the fact that foreign suspects have consistently comprised only a small proportion of penal-code suspects in Japan. “Would Japan be all right if it got rid of foreign residents?,” they ask in the book entitled “Gaikokujin Hoimo [Fencing in Foreigners]”, then assert that “approximately 98% of crimes are committed by Japanese.”. Given that most crimes are committed by Japanese, they argue, blaming migrants for Japan’s crime problem is nothing but an expression of discrimination.

What is truly at stake in Japanese immigration policies, according to migrant-support activists, is not public safety but human rights and human security. Every nationality includes some criminals, they argue, thus the existence of a small number of foreign criminals does not justify enhanced immigration control, which threatens the liberties of all foreign residents.

Their discourse of human security depicts migrants as systematically marginalized people despite their indispensable contribution to the Japanese economy, and accuses the Japanese state of unjustifiably depriving migrants of their human rights in the name of law and order. When the Japanese government treats unauthorized migrants as criminals on the basis of their legality, activists denounce the state as immoral because they think the Japanese state has exploited and depended upon migrants’ labor without giving workers proper acknowledgment and respect. When the Ministry of Justice implemented an online system for the Japanese public to report unauthorized residents in 2004, Torii Ippei, a union leader and board member of Ijuren wrote: “The Ministry of Justice is to solicit information about ‘illegal residents’ by emails? Outrageous. … The word ‘ungrateful [on shirazu]’ crossed my mind. They took advantage of migrant workers when [Japanese businesses] were short-handed and then disposed of them when they did not need workers any longer. On top of that, they blame these workers for contradictions in society by calling them ‘a hotbed of crime.’” .

The Japanese government sees removing unauthorized migrants and restricting visas as an effective solution for the crime problem. For migrant-support activists, alienating foreign residents in the name of crime control is not only unjust but also impractical and ineffective. The alternative solution they propose is the establishment of an egalitarian society without discrimination that can only be achieved through social integration.

Sources of alternative power: Autonomy and expertise

Scholars argue that the Japanese state has the overwhelming power to “mold” Japanese civil society and systematically suppress voices that challenge it further argues that the lack of professionalization, measured by the number of full-time staff and the possession of official legal person status [6], deprives Japanese civic groups of the capacity to be effective advocates.

This paper argues that the low level of institutionalization, a characteristic that Pekkanen identifies as weakness of Japanese advocacy, is the source of their strength at the same time. While the lack of certified status may limit the organizational capacity of NGOs, it also affords them autonomy from the state. Similarly, an insufficient number of dedicated staff members is an ongoing problem among these groups, but this very feature also encourages each member to develop multi-faceted expertise and creates a space for part-time activists who bring their professional expertise to the movement. Taking notice of this dual effect of the lack of institutionalization is critical in order to understand how civic advocacy works in Japan.

Autonomy

Ijuren and its affiliates consciously maintain their distance from the state. While Ijuren member groups collaborate with local governments, receive their funding from and communicate with legislators, they are highly cautious not to allow authorities to intervene their activities. As a result, migrant-support NGOs tend to shy away from the state-certified status of Non-profit organization (NPO). As of 2004, only 6 out of 78 migrant-support NGOs in the Tokyo and Kanagawa area acquired official status as an NPO .

Migrant-support activists are highly aware of the fact that the state-certified status is simultaneously a source of legitimacy and a vehicle of surveillance and control, thus carefully maneuver around it. Ms. Koto, the secretary general of one NGO and Mr. Yoshida, the representative of another, told me they would not care for NPO status because its benefit is too small considering the nuisance of having to make financial reports and the risk of government intervention.

When activists take advantage of the legitimizing power of the state by having their organization certified, they try their best to dodge its restricting grip. Strategic use of multiple organizational memberships is a common strategy used by Japanese activists to grapple with this dilemma. Ms. Sawada, who belongs to multiple international-student support organizations, carefully chooses which organizational title she uses when she makes a public statement. She is a core member of an organization that receives substantial governmental funding. However, if she raises an issue that entails a conflict with the state, such as protesting against the portrayal of international students as criminals by the government, Ms. Sawada chooses to use the name of another organization that does not receive government funds so that she can avoid possible intervention by the funding agency.

Expertise

Pekkanan (2006) attributes weak advocacy in Japan to the lack of professionalization among civic groups in Japan. If we apply Pekkanen’s measures of professionalization, i.e., the possession of an official status and dedicated staff, to Ijuren and its affiliated organizations, they are hardly professional. This paper, however, considers professionalism as a more complex property. Professionalism in civic participation entails at least two dimensions. One is institutionalization, i.e., the level of organizational resources and capacity as an institution, and the other is expertise, i.e., the passion of specialized knowledge and skills. Pekkanen’s measures capture only the former and fail to acknowledge the latter.

Ijuren organizations are low in institutionalization but high in expertise. Ijuren activists routinely exchange information and closely follow up with changes in immigration policies and administrative practices. As experts of immigration issues, they are often asked to give talks to community groups, academic institutions and even to government offices. Their expertise makes them capable and effective actors in the contentious politics of immigration.

The expertise of migrant-support NGOs comes from three sources. First, activists have direct contacts with unauthorized migrants, which provide them with alternative experiences and perspectives. Chronically short-handed, migrant-support activists typically wear multiple hats. The majority of advocates who lobby, protest and publish are simultaneously case workers: union workers who help migrant workers collect their unpaid wages; medical hotline workers who search for affordable medical care for foreign residents; education NGO members who help migrant children with school work and provide parent consultations; and facilitators of migrant women’s self-help group who assist survivors of domestic violence to access the care and resources that they need to start new lives.

Direct experience with migrants provides activists with a strong basis for their version of reality. Mr. Kanashima, who has played a central role in scrutinizing crime statistics, said that he became skeptical of the government’s crime-migration nexus argument because it was very different from the sense he got from the field [genba kankaku]. Mr. Watada, a founding member of Ijuren, also said his intuitive sense of reality [hada de kanjiru jikkan] suggested to him that most unauthorized workers would not have time to commit crimes because they were too busy working to send remittances back home.

Secondly, their informal organization opens the door to part-time activists who bring their professional knowledge to the movement. In general, migrant-support NGOs are open to visitors who share their concerns and motivated newcomers quickly become much-needed helping hands. Lawyers, public-sector workers and young academics are vital part-time participants in migrant-support activism in Japan. These legal and administrative professionals volunteer their expert knowledge in drafting legislative proposals and strategizing for negotiations with bureaucrats. The very fact that migrant-support groups lack full-time staff creates more opportunities for part-timers, allowing the movement to make use of the very precious professional expertise of moonlighting activists.

Finally, the legacies of previous movements provide migrant-support NGOs with expertise in civic activism. While migrant-support activists range widely in terms of age and background, many senior members participated in the student movement in the 1960s known as Zenkyoto, when activism was pervasive and confrontations with the state were fierce. Some also had first-hand experience in the labor movements and zainichi Korean movements during the 1970s and 1980s. Experiences from these larger and more intense movements have informed their critical view of the government and the mobilization tactics of contemporary migrant-support activism. In an interview, Mr. Watada stressed significant legacies of preceding movements by describing them as “very important lines of movement [that] came together and created the backbone [of Ijuren].”

Some activists further developed strategic expertise by participating in other movements. Mr. Akita, a union-affiliated Ijuren member and former Zenkyoto activist, commented; “We [Labor unions] have a historical advantage in tactics. There are some important points. You should not meet with the police alone, for instance. If you have a drink with them, limit it to a cup of coffee. Never let them treat you. Young people in recent peace movements do not understand this well, so they go for coffee and then for a meal. Then others suspect that person is a spy.”

Migrant-support NGOs in Japan thus present an interesting contrast between institutionalization and expertise; their lack of institutionalization makes each member a more well-rounded and knowledgeable advocate, and opens the field to part-time volunteer activists with highly valuable professional skills. Furthermore, legacies of student movements and zainichi Korean movements in the previous era provided migrant-support activism with a pool of expert activists.

Asserting an alternative discourse

The combination of high level of autonomy and expertise and low level of institutionalization shapes the way in which migrant-support NGOs perform contentious politics. While they occasionally carry out mass-demonstrations, the strategic focus of their advocacy is on direct confrontations or negotiations with key actors of immigration politics, which requires expert knowledge more than financial resources.

In explaining the significance of their actions, Mr. Kanashima uses the analogy of an Othello Go game. An Othello game uses black chips and white chips, and if a line of white chips is sandwiched by two black chips, they are all flipped into blacks. Whichever color that dominates the board in the end wins the game. Like in an Othello Game, Mr. Kanashima argues, strategic placement of effective challenge is critical in social movements in Japan. “In Japan, there is no need to change the opinions of the majority in order to change society,” he says. “Society will change if we make a convincing proposal; the opinion will be discussed in the Diet and will yield the policy change. No matter what the majority’s opinion is, society changes if a policy changes or if we win in court. I call it the Othello game theory; even though the middle is white, if we can turn the corners black, we can flip them all black.”

Autonomy and expertise of Ijuren-affiliated NGOs allow them to be a well-informed black chip that openly challenges the government. In domestic politics, Ijuren and its member organizations maintain ties with liberal legislators and set up meetings with government bureaucrats to express their concerns and grievances. Every year, they carry out an event called shocho kosho (ministerial negotiation), in which representatives of NGOs directly question representatives of multiple ministries. In shocho kosho, activists report unreasonable arrests of unauthorized migrants on the street, question the legitimacy of harsh crackdowns, and demand explanations from responsible ministries. While their questions are typically greeted with formal but empty answers, government representatives are made aware of their watchful eyes and willingness to hold the government accountable for their problems and errors.

Toward international bodies, migrant-support NGOs serve as independent experts on immigration policies and practices in Japan. They send representatives to international meetings to report insufficient human-rights protection for foreign nationals in Japan and host representatives of international organizations to give them access to information that the government is unwilling to provide. One recent successful example involved meetings with Doudou Diene, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, followed by filing a grievance. Their claim was successfully incorporated in Diene’s 2006 report to the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, which condemns “xenophobic and racial statements against foreigners” made by elected officials in Japan with “total impunity” .

At the same time, migrant-support activists compensate for their lack of organizational resources in a creative way. Unlike large and well-staffed non-profit industries in the United States, migrant-support NGOs in Japan do not have resources to expand their organization to cover new issues that constantly arise. Therefore, instead of branching out, they form cross-organizational taskforces to handle a large number of issues. Taskforces are flexible; they meet on a regular or on-demand basis, typically at one of the participating organization’s facility; they stop meeting once the issue is resolved or the group loses its significance for any other reason. This taskforce method allows NGOs to maximize limited organizational resources and to handle a large number of issues with a small number of people.

Gaikokujin Sabetsu (discrimination against foreigners) Watch Network is a taskforce that formed in February 2004 in response to the growing portrayal of migrants as criminals. Participants hold monthly meetings, carry out public awareness campaigns and send statements of concern to mass media that misconstrue migrants as criminals. In 2005, Sabetsu Watch members succeeded in bringing representatives of the National Police Agency to a discussion table, where they expressed concerns about an overemphasis of the criminality of foreigners in police reports.

Thus migrant-support NGOs organize their political actions to play to their strengths. Highly focused negotiations with domestic and international decision-makers are made possible by their knowledge of immigration laws and administrative practices. Furthermore, their political autonomy affords space for them to directly confront the government.

Conclusion: Is this alternative voice significant?

Migrant-support NGOs challenge the discourse of foreign criminality by focusing their discourse on human security. Using their expert knowledge and autonomous status, migrant-support activists directly confront policy makers and government bureaucrats.

But how much political impact does their voice carry? The reach of their message is clearly limited compared to the foreign criminality discourse, which floods the mass media. Furthermore, their challenges to government officials in the meetings are typically greeted with bureaucratic formal responses and hardly yield direct products.

Does this make their challenge insignificant? Although it may appear to be so at first glance, equating the lack of direct, visible political impact with a lack of political significance is too narrow a view. The presence of a vocal, watchful, and knowledgeable group of people who are willing to confront the state on behalf of migrants is critical because it forces government officials to be more careful and more accountable with what they say and do. This effect may not be readily visible, but cannot be underestimated.

Using Mr. Kanashima’s analogy, I conclude this paper by asserting that migrant-support NGOs serve as the precious black chips in the white-dominated Othello board called immigration-crime politics in Japan. They keep in check the moves of the white chips that insist migrants are a crime problem and continuously remind them of an alternative perspective and of the presence of people who stand up for this cause. And along the way, they may change the color of a few pieces here and there.

References

Diene, Doudou. 2006. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, DouDou Diene, on His Misssion to Japan (3-11 July 2005), Annex.” United Nations, Geneva.

Gaikokujin Sabetsu Watch Network. 2004. “Gaikokujin Hoimo: Chian Akka no Sukepu Goto [Foreigner Encircling Net: Scapegoat for “Worsening Security”].” Tokyo: Gendai Jinbunsha.

Garon, Sheldon. 1997. Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Keisatsucho. 2003. Heisei 15 nen Keisatsu Hakusho [2003 Police White Paper]. Tokyo, Japan.

Pekkanen, Robert. 2003. “Molding Japanese Civil Society: State-Structured Incentives and the Patterning of Civil Society.” Pp. 116-134 in The State of Civil Society in Japan, edited by F. Schwartz and S. Pharr. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

—. 2006. Japan’s Dual Civil Society: Members without Advocates. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Roberts, Glenda S. 2003. “NGO Support for Migrant Labor in Japan.” Pp. 275-300 in Japan and Global Migration: Foreign Workers and the Advent of a Multicultural Society, edited by M. Douglass and G. S. Roberts. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

Shipper, Apichai W. 2004. “The Impact of the NPO Law on Foreigners Support Group in Japan.” The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, Tokyo.

—. 2005. “Criminals or Victims?: The Politics of Illegal Foreigners in Japan ” Journal of Japanese Studies 31:299 – 327.

—. 2006. “Foreigners and Civil Society in Japan.” Pacific Affairs 79:269-289.

Torii, Ippei. 2004. “Meru deno Johouketsuke o Chushi Saseyo [Let’s Make Them Stop Accepting Information via Internet].” Migrants’ Net 67:1.

Wolferen, Karel van. 1989. The Enigma of Japanese Power: People and Politics in a Stateless Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Ryoko Yamamoto is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. Her dissertation examines the discursive construction of migrants as a crime problem in contemporary Japan. This article was posted on Japan Focus on September 15, 2007.

Notes

[1] Shuto Tokyo ni Okeru Fuho Taizai Gaikokujin Taisaku no Kyoka ni Kansuru Kyodo Sengen [The Joint Statement Concerning the Enhancement of Measures against Illegal Foreign National Residents] , October 17, 2003

[2] The most commonly used crime statistics in Japan is penal-code offense/offender (keiho-han). Penal-code offenses include such crimes as homicide, robbery, larceny, assault, rape, arson, etc. Immigration law violations, drug offenses, and prostitution are special-code offenses (tokubetsuho-han) and are not counted in penal-code statistics. The distinction between penal-code offenses and special-code offenses is administrative rather than conceptual. The National Police Agency uses two foreigner categories: rainichi foreigners and other foreigners. Rainichi (literally meaning “visiting Japan”) foreigners refers mainly to foreign-national visitors and residents who do not have permanent residency in Japan. The “other” category includes permanent residents (including zainichi Koreans and Chinese), U.S. military service persons and their families, and non-Japanese nationals whose immigration status is unidentified. The governmental discourse of foreign criminality exclusively focuses on rainichi foreigners.

[3] Sangokujin, literally meaning “people of a third country,” is a derogatory term referring to former colonial subjects from Korea, Taiwan and China who continued to reside in Japan after Japan’s surrender in 1945. In a public speech on April 10, 2000, Ishihara urged the Self Defense Force to prepare for a possible riot by illegal foreigners, or “sangokujin,” in case of emergency such as an earthquake. His deliberate use of a derogatory term received strong criticism domestically and internationally.

[4] The National Police Agency uses two foreigner categories: rainichi foreigners and other foreigners. Rainichi (literally meaning “visiting Japan”) foreigners refers mainly to foreign-national visitors and residents who do not have permanent residency in Japan. The “other” category includes permanent residents (including zainichi Koreans and Chinese), U.S. military service persons and their families, and non-Japanese nationals whose immigration status is unidentified. The governmental discourse of foreign criminality exclusively focuses on rainichi foreigners.

[5] Press conference on April 12, 2000

[6] Legal person status requires application to a government ministry and acceptance of a monitoring-monitored relationship with that ministry.