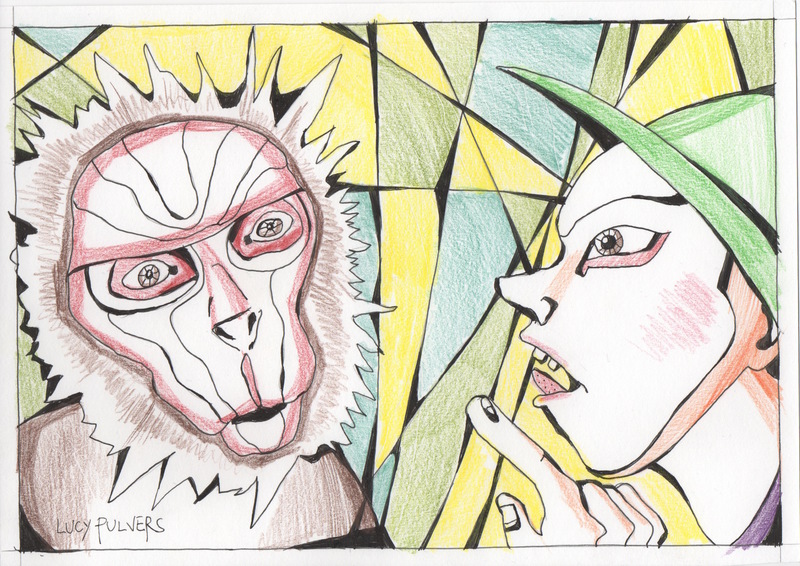

Illustrations by Lucy Pulvers

The two great poets of Iwate, Ishikawa Takuboku and Miyazawa Kenji, were born 50 kilometers and 10 years apart (1886 and 1896) and went to the same middle school in Morioka. They both died young of tuberculosis: Takuboku at 26 in 1912 and Kenji at 37 in 1933.

Takuboku was already on the way to being mega-famous while he was alive; Kenji did not receive such superstar status until many decades after his death. Both are today considered voices for progress and activism in many spheres of social activity. Takuboku is more political than Kenji; Kenji more aware of the natural and cosmic forces determining our fate than Takuboku. Had Takuboku lived longer, it is very possible that they would have met. As it is, they are the soul brothers of Meiji Japan.

“The Tale in the Woods” was published in the September 20, 1907 issue of the alumni magazine of Morioka Middle School, the present-day Morioka No. 1 High School. Kenji wasn’t to enter the school until a year and a half later; but, judging by the tenor of the stories he subsequently wrote, “The Tale in the Woods” clearly influenced him.

Of the two stories published here, Takuboku’s tale requires no detailed commentary. It takes up humankind’s arrogance as the self-styled lords of all creation. Environmentalism was certainly in the air in late Meiji. The word “ecology” was used by Minakata Kumagusu, among others, and Japanese activists such as Tanaka Shozo were fighting powerful forces in industry and government to save our natural resources from devastating pollution.

Kenji’s “The Magnolia Tree” is, if you will, a horse of a different color. I’ve elaborated on some of its details to clarify its context.

Kenji’s most popular stories, such as “The Restaurant of Many Orders” and “Gauche the Cellist,” have a clear narrative line with a moral at the end. They are European-style tales whose narrative elements are easy to understand.

But Kenji’s oeuvre contains many prose works that are not so accessible to readers. They are still morality plays of a sort, but their morality is heavily imbued with Buddhist thought and imagery. Yet, for sheer lyricism and starkness, some of them are little masterpieces. And they tell the reader much more about the “inner Kenji” than his more traditional-style stories.

“The Magnolia Tree” stands in Kenji’s oeuvre, along with “Indra’s Net,” as one of his most exquisitely lyrical works. This story is a key that opens up the mind of Miyazawa Kenji to us, revealing his true self.

As in “Indra’s Net” the narrative is about a lone traveler. It is when Kenji literally throws himself into the unknown (and puts himself at its mercy) that he makes his discoveries about the nature of the individual in nature.

He wrote a poem called “Departure to a Different Road” whose opening lines describe this very well …

The earth grates at my feet

When I land alone and without destination

Between the moon’s bewitchment

And this monstrous plate of snow.

The void blackened by cold

Fronts hollow against my brow

In many of Kenji’s prose works and poems, nothing stands between him and the harshest nature. And often he does not even know what he is doing there in the first place. He is lost … and yet he relishes the condition.

I believe that Kenji’s alter ego in “The Magnolia Tree,” Ryoan, has found himself in the Himalayan region of India. This tree is most likely to be a magnolia champaca, an evergreen revered in India from time immemorial. Magnolia champaca’s flowers are either yellow or white and very fragrant.

“The Magnolia Tree” is rather surrealistic. If it had been written in French by Paul Verlaine or Stéphane Mallarmé, the world would have discovered this poetic story and labeled it “symbolist.” But “The Magnolia Tree” is not surrealistic or symbolist. It is pure “Kenji realism.” It is a story about a man’s confrontation with his other self; and through this confrontation he more deeply understands himself. As such, it is not dissimilar to the man’s encounter with the monkey, his “former self,” in Takuboku’s story.

I know of nowhere else in all Kenji’s works where this confrontation with the self—through the imagination—is so clearly stated.

What is Kenji telling us here?

He is telling us that if we take a journey inside ourselves, a journey of self-discovery, and if we excite our imagination, we will come to realize that the landscape we see outside—all creation—is also entirely inside us all the time. This is the prime lesson of Miyazawa Kenji. If we realize this, we can begin to understand that we are one with the universe and come to value mercy and love for other humans, animals and all other phenomena of nature.

This is what Kenji means by “the training ground of spring” (春の道場), a phrase he uses elsewhere in his works. Spring is the season when nature comes to life. But it is a season not merely to be appreciated for its beauty, though this is certainly a part of it. It is a place where we can train ourselves to observe everything and get closer to our inner self.

The central image of this story is the single tree with the two children standing on either side of the trunk. The tree is a symbol of Nirvana.

But we need not be tied down by Kenji’s religious tenets. For us the tree can represent any pure goal that we wish to achieve, so long as it is achieved through selflessness and love.

The poetic prayers are carried on the fragrance of the petals of this magnolia tree. This, too, is what Kenji means by the training ground of spring. Nature communicates with us. It tells us what we are like. If we have the insight to love nature as we should, then we will love ourselves and be free to help others. The message of Takuboku’s monkey in “The Tale in the Woods” again resonates.

The man who is Ryoan’s (Kenji’s) alter ego tells him that the flatness is not real flatness, but only flatness in comparison with the steepness. All is relative in our observations to where we are and when, as Einstein has taught us.

Good and evil are intertwined in this world, too, as we see at the end of the story. All causes and all effects, including famines and epidemics, are an integral part of nature and the nature of man.

Kenji is telling us not to hate when we are confronted with malice, not to give in when we face famine or epidemics. This is the same message as the one in his most famous poem, “Strong in the Rain.”

The bow at the very end is a bow in respect to one’s own imaginative powers. We all have the ability to access our imagination.

Imagination is the real sixth sense.

|

THE TALE IN THE WOODS

By Ishikawa Takuboku

Translated by Roger Pulvers

Below I have recorded a tale in the woods.

A man walked into the woods.

A monkey sitting on a branch of a very tall tree posed a question to the man.

“We share ancestors, so why do you human beings look down on us?”

The man answered the monkey this way.

“We’re clever, unlike you stupid monkeys. Would we human beings have produced so many great heroes in our history if we came from the likes of you?”

The monkey spoke again.

“Oh, you human beings are so pathetic! You have all simply forgotten the past. Don’t you see that the very fact that you are alive right here and now is because we have the very same ancestors? Those who have forgotten their past will have no future. There will be neither progress nor happiness in the future if you get too big for your britches and think that you’re the cleverest animal and that now is the best time ever. I really pity you. It probably won’t be long before human beings vanish from the face of the Earth.”

The man spoke up in anger.

“What the hell are you talking about, damn monkey! You haven’t got brains as big as ours, so how could you possibly ever be a match to us humans? You monkeys don’t have houses like us. And you don’t even wear clothes like we do, right? Don’t you know that we’re eating much more delicious things than the nuts you feed on?”

The monkey laughed and spoke again.

“Ha ha ha! Our hair is natural clothing that keeps us healthy during the four seasons. If you human beings had the brains you were born with, you’d be living lives in tune with nature.”

The monkey didn’t stop there.

“Our home is the entire forest. And not only these woods but all the woods all over the world are our ‘home sweet home.’ Do you really consider suddenly waltzing into our home without so much as a how-do-you-do something that a proper human being does?”

The human being’s voice now became rough and hoarse.

“Get down from there! Come on down! I’m tellin’ you to get yourself down here and say once more to my face what you just said!”

The monkey spoke.

“My, you’re a guest with a beastly way of talking, aren’t you! I happen to be the master of this house, I’ll have you know. No one can tell the master of his house what he has to do. You’re the guest here, sir, so I suggest you start by paying your respects to the master of the house. Now, how about coming on up here and feasting on some horse chestnuts with me.”

The man looked up into the tall tree and saw the monkey in the branches looking down on him and beckoning him with his paw. All he could do was look up like that, seething with anger at the monkey who was beyond his reach.

The monkey spoke again.

“Oh, you human beings are truly to be pitied! Humans can’t stand on their own two hands. They can’t grasp things with their feet. Look, our four legs are not only legs but hands as well. If you look at the way the arms and legs of human beings are attached, it’s plain as day that they could once do whatever we can do. But the fact is that you can’t do it now. The history of your limbs, if you take a step back, is just that: history. Some day the time will come when your limbs won’t be good for anything at all. That’ll be the result of human beings being such sloths!

“The only progress that humankind is making day in and day out is progress in the history of carelessness and neglect. Look, the mechanized civilization that human beings brag about so much is, in the end, run by the very diabolical hand that is turning all of you into a race of lazybones!”

The man screamed out his words.

“How dare you, you cocky beast! Come down right this instant!”

The monkey spoke.

“There’s no animal in this world as backward as the human being. Take a look at us. We share ancestors with you. Not only can we move with complete freedom on the ground, we can move up and down at will. You’re stuck on the ground. Sure, you once could live in trees, but that was donkey’s years ago. Then you slid down to the ground with your fellow snakes and toads. If that isn’t a ‘come down’ I don’t know what is. Think it over and ask yourself: Which is closer to Heaven, the horizon that human beings stand on or the trees we sit in … and which is closer to Hell?”

The man screamed his words out again.

“Ponder this, revolting little beast! All we’d have to do is chop down the trees all over the world. Where would your home-sweet-home be then, eh? If we did that, you’d have to stand on bended knee in front of us, bow your head low and beg us your salvation.”

The monkey spoke.

“Ah, so finally a human being has spit out his most evil thoughts. Human beings throughout their history have plotted their hateful rebellion in every corner of the world, snuffing out Nature, brutally butchering everything that is true and beautiful, chopping down trees, digging away mountains and burying rivers to make their smooth roads. Yet those roads – the borders between all that is true and beautiful and all that is not – do not lead to the heights of Heaven but rather to the gates of Hell. Human beings have forgotten where they came from and have turned their backs on Nature. Oh, could there be a more cursed and doomed animal in this world than the human being?”

Having said that, the monkey felt deeply sorry for human beings.

Though the human being below the tree may have sensed that there was some truth behind the monkey’s pity for his kind, it didn’t mean that he was prepared to recognize it as truth. So he started to walk out of the woods, grinding his teeth in fury.

The monkey watched him and spoke.

“Sir, where are you heading?”

The man’s voice trembled.

“Stay where you are. I’m gonna make you sorry for what you just said. I’m goin’ home and I’ll be back with my rifle.”

But before the man had finished speaking, several huge horse chestnuts sailed down from somewhere, clunking hard against his head.

In a flash the branches of the trees creaked, the leaves rustled … and the old monkey was no longer to be seen in those woods.

He had jumped from branch to branch and flown through the air until finding refuge far far away deep in mountains into which the sun slips out of the white clouds and disappears.

|

THE MAGNOLIA TREE

By Miyazawa Kenji

Translated by Roger Pulvers

A damp and gloomy fog hung over everything.

Ryoan was making his way under the blanket of fog, tramping up and down the steep slopes of the valley. He plodded on and on, the sole of his shoe half worn through, from peaks that reached to the heavens to the darkest deepest bottom of valleys, and once again upward to the next cliff towering swallowed up in fog.

The thought occurred to him that if it were possible to swim through that fog he would sail like the wind from one cliff straight to another. As it was he had no choice but to trudge up the precipitous punishing surfaces of these monstrous sculptures then down again to the more flat planes below, his body burning and his breath panting as he crawled over the earth.

Black jagged boulders whistled in the freezing fog. Though feeling desolate and totally alone, he put his heart and soul into trekking up and down. Even the huge clump of little blackish shrubs growing in the depths of the valley looked cruel the way they absorbed all the light around them. And yet, this did not deter Ryoan, who continued all by himself on his way from one notched peak to the next.

No sooner did the fog suddenly glow with a dim light than it slid back into half-darkness. This occurred again and again. The dim whitish light would not give into night.

Ryoan came to a gently sloping area where lustrous snake beards blanketed the ground. He threw himself down, dozed off and was soon dead to the world.

“This is your world, you know. This is the world that suits you down to the ground. But really, more than that, it’s the landscape inside you, you know.”

Someone, or maybe Ryoan himself, was screaming that, over and over again, not far from his ear.

“That’s right, that’s right, that’s absolutely right. This is obviously my landscape. It’s me. So there’s not much I can do about it,” replied Ryoan, nodding off.

“The seductive clump

The training ground of spring

Where you learn

To treat all

Without malice”

The voice could clearly be heard coming from somewhere. Ryoan opened his eyes. The chilling fog permeated his entire body. The fog was now so white that it hurt the eyes, and the blue slope of snake beards glimmered faintly inside it.

Ryoan dashed down the mountain. But he caught his foot in one of the shrubs and tumbled to the ground. He stood up, a wry smile on his lips. A precipice of small trees appeared suddenly before his eyes. He climbed up it, clinging to the branches of those spicewood trees. The spicewood trees sent a faint fragrance into the fog, and the fog gave Ryoan something soft smooth and milky white in return. Ryoan smiled as he clawed his way up the side of the mountain.

It was then that the fog turned all gloomy, and Ryoan threw it that faint smile of his. At that, the fog brightened up again.

Finally, he reached a plateau of withered grass. Standing there, he felt all warm and golden, and he sensed that the faint odor of sweat was leaving his body in thin threads, surging up into the fog. A single spectacular black horse emerged, prancing out of that thought, and disappeared into the fog.

The fog, in an instant, pitched and rolled, and Ryoan caught sight of something that looked like floating amber molecules, glittering brightly. In a flash those amber molecules were gleaming gold, then fresh green, pelting down like the rains.

Ryoan’s dim shadow fell onto the withered grass. A sliver of his fragrant odor flashed and glistened, traveling straight through the suspension of that fog and amber-green mass. But before he knew it, the whole scene was drenched in gold again.

The fog melted away. The sun swayed like a liquid, to and fro, in the newly polished azurite sky, and the bright wax of unmelted fog that did remain dripped down, here and there, into the valley.

“Ah, that’s where I’ve just been, that awful sheer valley. But, what a spectacular sight this is! And, let me see, there’s that, too!”

Ryoan didn’t believe his eyes. In the countless crags of the valley sheets of white magnolia flowers were blooming, silver in color when struck by the sun, more like snow where not.

“Enveloping the steeply notched

cliffs on the heart

sheets of magnolia”

This voice from somewhere could clearly be heard. Ryoan took in the scene with a heart full of light.

There was a single tall magnolia tree standing not far in the distance, with two children on either side of its trunk.

“Ah, it was those children who were singing a moment ago. But wait … they’re not just plain kids.”

Ryoan took a really good look at them. They were like a dream in a fasting dawn, dressed in gossamer and sacred raiments, glittering in the light of the sun. But it seems that the song had not been sung by them. That’s because one of the children had been singing in a thin voice from long before that, glaring up to the very top of the magnolia tree.

“Santa Magnolia

Shining bright to your tips

Over your every branch”

The child on the other side replied …

“Silver dove soaring

To the heavens”

The first child sang again …

“Heavenly dove descending

From the heavens”

Ryoan quietly continued on his way.

“This tree is Nirvana. Where are we?”

“We don’t know,” answered one of the children humbly, raising his bright eyes.

“Yes, the magnolia tree is Nirvana.”

The unwavering clear voice came to Ryoan from behind. He quickly turned around. A man just like him, dressed like the children, was standing perfectly straight alongside them.

“Was it you singing back there before?”

“Yes, me. But it’s also you. If you want to know why, it’s because you can sense me.”

“Yes, I can … thank you … it’s me … and it’s also you. It’s because, whatever is me is also in you.”

The man laughed. The two of them bowed a little to each other for the first time.

“It’s really so flat here,” said Ryoan, gazing at the beautiful golden grassy plateau behind him.

“Yes,” said the man, smiling, “it is flat. But the flat here is only flatness in comparison with the steepness. It’s not a real flatness.”

“That’s right. It’s flat because of the steep mountains I climbed to get here.”

“Look! Those steep mountains are covered in magnolia blossoms.”

“I see. Thank you. So, then, the magnolia is Nirvana. Those petals are softer than the goat’s milk of paradise. Its fragrance wafts exalted poetic prayer to those who have attained Enlightenment.”

“It is all goodness itself.”

“Whose goodness?” asked Ryoan, taking a last look at the magnolias on the golden plateau and the steep faces of the mountains.

“The goodness of the Enlightened.”

His shadow fell, purple and transparent, into the grass.

“Yes … and it is our goodness, too. The goodness of the Enlightened is absolute. It appears in the magnolia tree, as it does in the cold boulders of the steep cliffs. The dark dense forests of the valleys and the rivers flowing on and on and the frequent revolutions and famines and epidemics that occur where those rivers flood … all is the goodness of the Enlightened. But here, the magnolia tree is the goodness of the Enlightened and also our own.”

The two of them bowed again respectfully to each other.

Recommended citation: Roger Pulvers, “In the Woods with Takuboku and Kenji — Soul Brothers of Meiji Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 23, No. 4, June 8 2015.

Roger Pulvers is the author of more than 40 books in Japanese and English. His novel “The Dream of Lafcadio Hearn” is published by Kurodahan Press.His most recent book is Illusions of Self: 200 Tanka by Ishikawa Takuboku Translation, Notes and Commentary.

Lucy Pulvers. Born in Kyoto and living in Sydney, Lucy Pulvers is an artist and illustrator. Her work has included illustrated ebooks for Phasminda Publishing. Her music video art can be seen on the

Related articles

• Roger Pulvers, Illusions of Self: The Life and Poetry of Ishikawa Takuboku

• Roger Pulvers, Miyazawa Kenji’s Prophetic Green Vision: Japan’s Great Writer/Poet on the 80th Anniversary of His Death

• Roger Pulvers, Miyazawa Kenji, Jane Marie Law, Indra’s Net: The Spiritual Universe of Miyazawa Kenji

• Robert Stolz, Remake Politics, Not Nature: Tanaka Shozo’s Philosophies of ‘Poison’ and ‘Flow’ and Japan’s Environment