Roger Pulvers

I A Walk Along the Shores of Shura

At the beginning of the third week of September in Hanamaki our thoughts turn, with the hand of the clock, to another world. The autumnal equinox certainly reinforces this; for this is the season in Japan of recalling those who came before us, a time when many Japanese people choose to visit the gravesites of their ancestors.

But Kenji died on 21 September, at 1:30 in the afternoon, to be exact. This year—2008—marked the 75th year of his passing, so perhaps that hand of the clock (so appropriately called hari, or “needle,” in Japanese) stopped momentarily on this day in Hanamaki.

I spent that morning walking the shores of the English Coast. This is, of course, that part of the bank of the Kitakami River that Kenji renamed “Igirisu Kaigan.”

Stone steps leading to Igirisu Kaigan

Stone steps leading to Igirisu Kaigan

I had been there any number of times in the past 39 years, since my first visit to Hanamaki in 1969, but this time was very special. It wasn’t only the fact of the anniversary of Kenji’s death that made it special. Entreaties to officials in Iwate Prefecture to get the dam controlling the flow of water in the Kitakami River were heeded, and the water level was sufficiently low to expose parts of the rock bed and the white “Dover-like cliffs” on the banks. If you knew where to look, you could see outlines of the footprints of mammoths that Kenji describes in his poetry below the water’s surface.

The Igirishu Kaigan on the Kitakami River in September

The Igirishu Kaigan on the Kitakami River in September

The city of Hanamaki has finally recognized the importance of this stretch of river and beautified it with walkways, lookouts and a host of flowers, many of which appear in Kenji’s works. On this particular Sunday the 21st, a light rain was falling. I walked along the river, on the narrow path that cuts through the cosmos and sunflowers—I even wrote a poem about the path called “Light Years”—and truly felt that this was the place Kenji called “the shores of Shura.” (Shura is one of the realms of existence, the one just below “Humans,” where pandemonium reigns…a kind of Buddhist Purgatory.)

That afternoon I went to the Miyazawa home that I visited in 1969, when I first met Miyazawa Seiroku, Kenji’s younger brother. From there we walked to the stone monument of Kenji’s most famous poem, “Strong in the Rain,” where the annual Kenjisai, or Kenji Festival, is held. This was the second time that I was attending this festival, the first being in 1970.

Hanamaki from Enmanji-Kanon

Hanamaki from Enmanji-Kanon

Before the festival began, we strolled along the rice fields below. The landscape was identical to that in Kenji’s time, save for the facts that the electricity poles were now concrete instead of wood and that an embankment had been built in recent years by one field to prevent flooding. Suddenly a rifle shot rang out. Having been raised in the United States, I instinctively shrugged my shoulders up to my ears. The others in our little group of Kenji scholars—all Japanese—didn’t flinch. No one knew where the shot was coming from. Perhaps, I thought, it was the hunters in “The Restaurant of Many Orders” warning us of the dangers of the wooded area there.

The Kenjisai is an homage to Hanamaki’s native son. Actually, the entire town now offers such homage to Kenji’s ever-presence in the form of a wide variety of Kenji goods from “Night on the Milky Way Cookies” and Kenji bookmarks to noren curtains on Kenji themes and a rice cake called “Kenji no Takaramochi,” or “Kenji Treasure Rice Cakes.” The long-distance bus from Hanamaki south is called the “Kenji Liner.” Hanamaki has been ideally transformed, in the spirit of souvenirs both concrete and abstract, into a recreation of Kenji’s self-styled utopian community, Ihatovo, the place where everyone looks after everyone else and all creation thrives in peaceful harmony.

The Kenjisai this year featured—after the usual speeches—children from the local schools reciting and singing Kenji poems; an impressive Mamasan Chorus of lovely ladies dressed in monpei and shiny white rubber boots; a high school production of a play titled, in clever parody, “Gauche the Pianica Player”; and a stirring performance of sword dances (kenbai) by a group of masked dancers. The sparks flying up to the sky from the bonfires that illuminated the dance brought to mind Kenji’s poetic masterpiece, “The Swordsmen’s Dance of Haratai.”

I spent only three days in Hanamaki this time, a long way to travel from Sydney for such a short time. But the clock stopped, if only momentarily, while I was there…and that path cutting through the cosmos by the shores of the English Coast seemed longer than ever.

Roger Pulvers went to Hanamaki to receive this year’s Miyazawa Kenji Prize.

II In harmony With All Creation

It is 75 years since Miyazawa Kenji died, but his poetry and passion speaks to our lives today

If the primary theme of human life in the 21st century is living in harmony with other animals and plants — and also preserving the bounties of the Earth — then Miyazawa Kenji is the Japanese writer who can most thoroughly help us to understand and pursue this theme.

Miyazawa died 75 years ago this Sunday, Sept. 21; but his profound ideas, expressed in exquisite prose parables and philosophical poetry, speak to us as if he were our contemporary. He truly considered himself to be in total harmony with all creation.

Strong in the Rain

Strong in the rain

Strong in the wind

Strong against the summer heat and snow

He is healthy and robust

Free from desire

He never loses his temper

Nor the quiet smile on his lips

He eats four go of unpolished rice

Miso and a few vegetables a day

He does not consider himself

In whatever occurs . . . his understanding

Comes from observation and experience

And he never loses sight of things

He lives in a little thatched-roof hut

In a field in the shadows of a pine tree grove

If there is a sick child in the east

He goes there to nurse the child

If there’s a tired mother in the west

He goes to her and carries her sheaves

If someone is near death in the south

He goes and says, “Don’t be afraid”

If there are strife and lawsuits in the north

He demands that the people put an end to their pettiness

He weeps at the time of drought

He plods about at a loss during the cold summer

Everyone calls him Blockhead

No one sings his praises

Or takes him to heart . . .

That is the kind of person

I want to be

© “Strong in the Rain” by Kenji Miyazawa; translation © Roger Pulvers

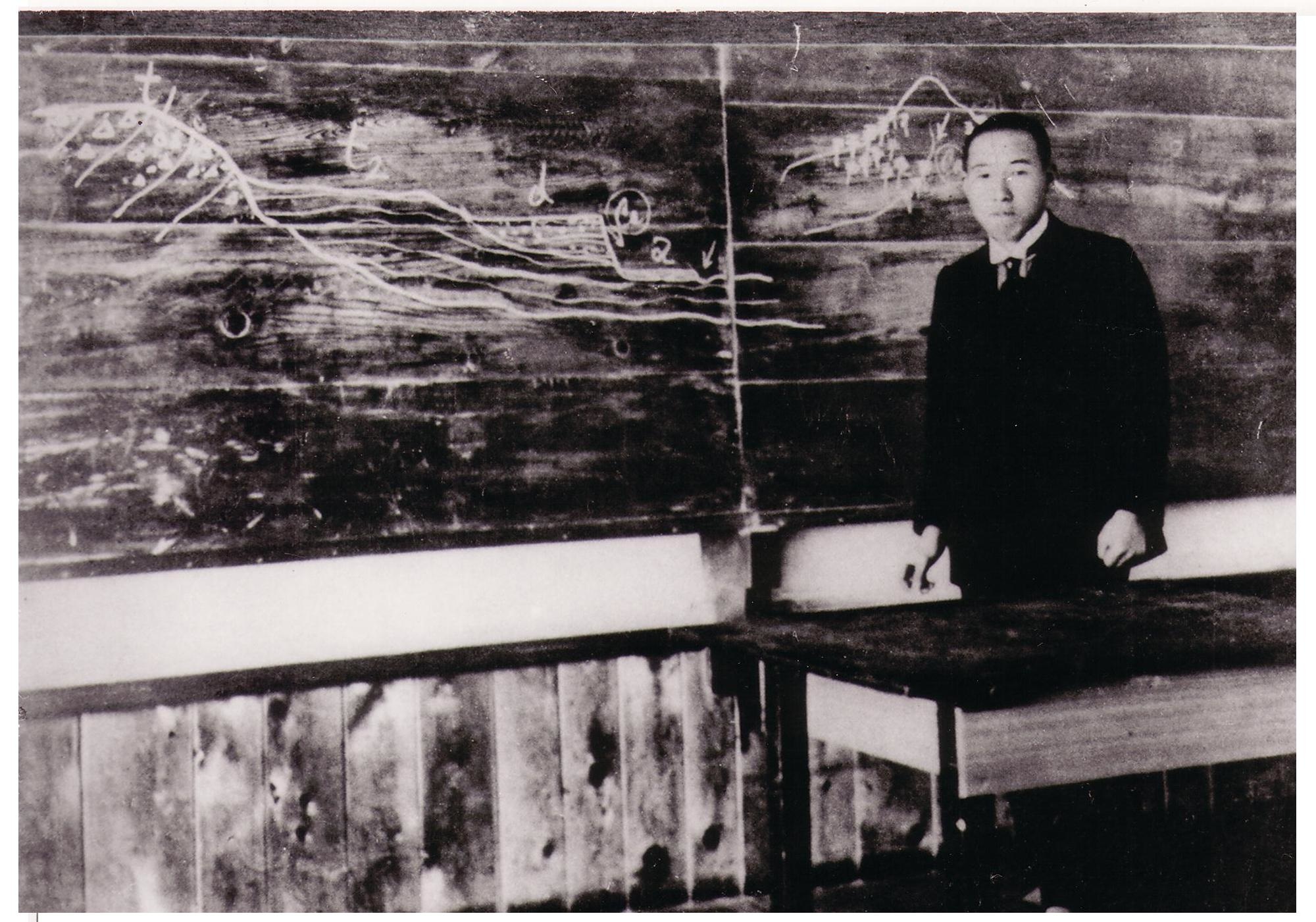

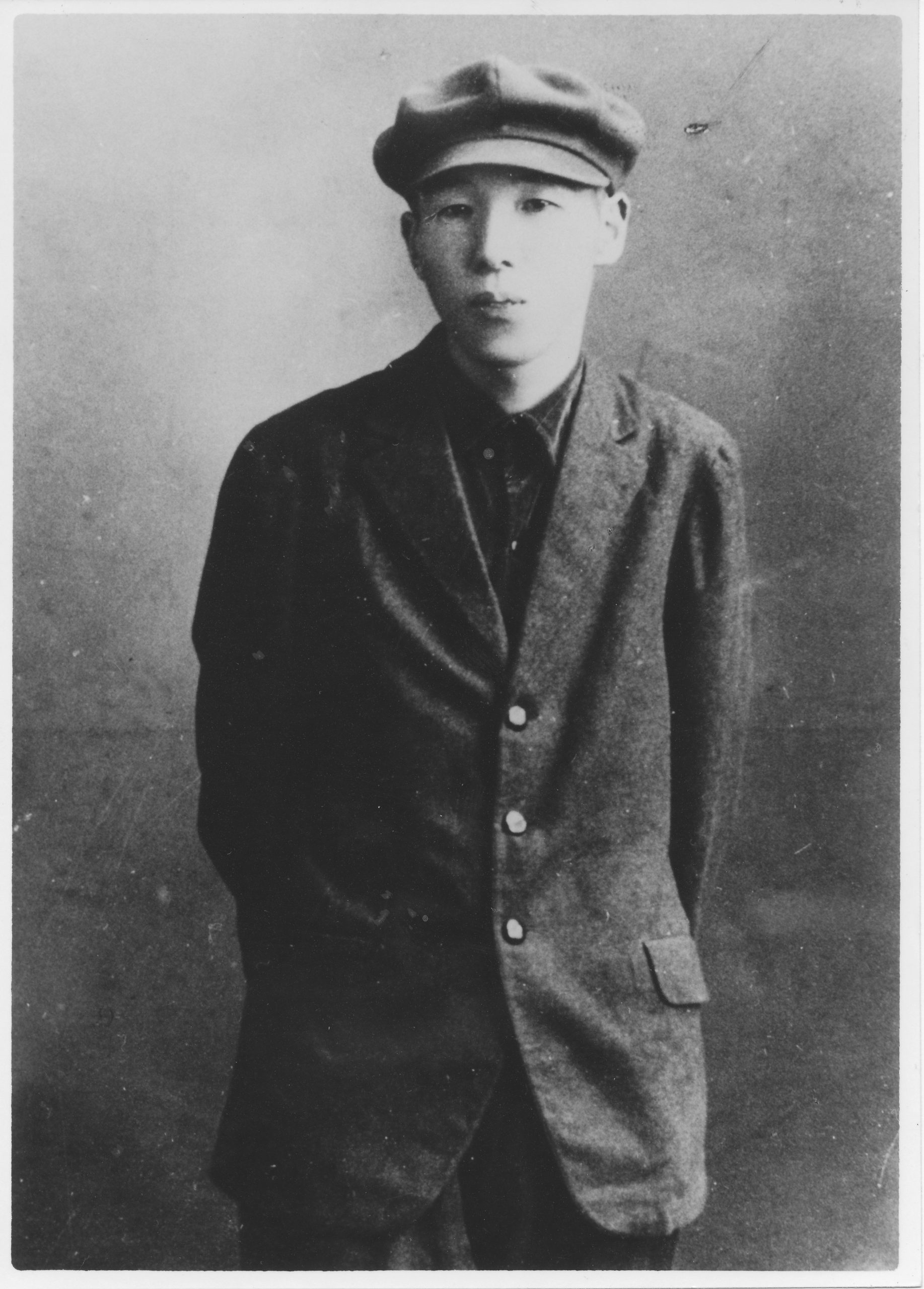

Kenji seated © RINPOO

Kenji seated © RINPOO

In his poem “Whatever Anyone Says,” he is oblivious to how this total identification with nature will be looked upon by others , . . Whatever anyone says I am the young wild olive tree Dripping radiant dew Cold droplets Transparent rain From my every branch

In “My Heart Now,” written in the grips of a grave illness, he tells us . . . My heart now Is a warm sad saline lake

Throughout his work, mountains are crumbling before our very eyes; rivers are being carved out and their course, diverted; light and air serve as the media of change; and a thick forest becomes, in the blink of an eye, a barren desert.

Miyazawa believed that the spirit of Japanese people would die if they did not continue to recognize beauty and find happiness in concord with nature. Humans, birds, insects, all creatures pass on; and it is the trees and the light and the wind that transport their messages into the future.

As a trained agronomist and geologist, Miyazawa’s poetic eye always turned to nature’s processes; and his intellect, too, was attuned to the logical causes and effects underlying them. Some of his poems sound like downright reports of an event made by a scientist to local officials.

One poem, only two lines long, is even titled “A Report” . . . The “fire” that just caused such alarm was nothing but a rainbow For an hour on end, its cords taut across the sky

Although he appears to be stretching it a bit here, there was apparently just such a long-lived rainbow in the sky above his hometown of Hanamaki on the afternoon of June 15, 1922. The upper part of this rainbow was said to have glowed red, like fire.

Miyazawa, then, saw himself as nature’s faithful recordist. While many consider him an author of fantasy stories, it is clear that he was an ultimate realist. It is in the context of this “Miyazawa realism” that we can approach his work in a fresh and relevant way.

Miyazawa was, I believe, more aware than anyone of the cost that Japan was paying and was to pay for its new industrial power. And yet, he was in no way a “back to nature” romanticist. He did not share the view that his country would be better off in a state of blissful nature-worship. He may have been an ardent, even fanatic, believer in the Nichiren Sect of Buddhism, but his take on progress was concrete, analytical and optimistic. It also relied on the necessity for each and every one of us to have a proper consciousness of the world and its problems and to take some action to alleviate misery and poverty.

In “Kenju Park Woods,” one of his stories, Kenju, an obvious alter ego of the writer, planted a cryptomeria forest. Heiji, a most unscrupulous ne’er-do-well, wanted Kenju to cut down the trees.

“Cut ’em down, I say, cut ’em down, will ya!”

Kenju stands his ground.

“No, I won’t!” he says.

Heiji proceeds to beat hell out of Kenju.

Later that year, Heiji dies of typhus and, 10 days later, Kenju too dies of the same disease. The message is that we who are alive at the same time may all share the same fate, whatever our beliefs may be, and events may at any time take us. The victim and the victimizer are linked, like two mountain climbers connected by a rope on a cliff in the snow. The victimizer requires salvation as does the victim. Consciousness of this will save us and the environment around us.

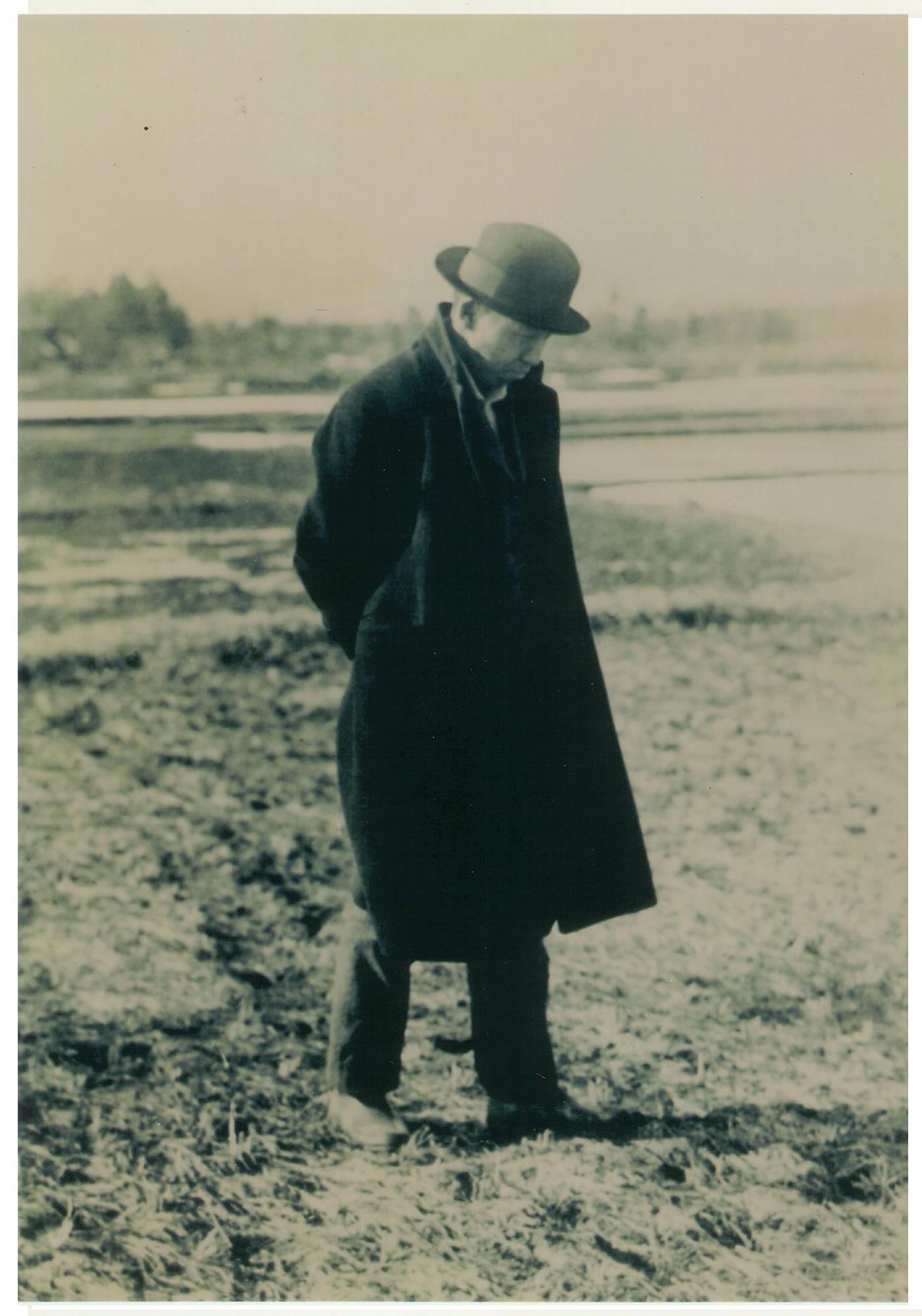

© RINPOO

© RINPOO

The people in Kenju’s village gradually come to value the forest that he planted, and its rows are given names: Tokyo Road, Russia Road, Road of the Occident . . . Miyazawa’s sensibility was cosmopolitan, though he never left Japan and did not even travel widely around his own country. In many ways he is like a Japanese combination of Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman.

In “Kenju Park Woods,” Kenju’s wisdom is recognized years after his death. It is the continued presence of the trees, the very spirit of Kenju himself, that stands as a source of genuine happiness for the people.

Astride the years: Kenji Miyazawa, who speaks to us now as if he were among us

Astride the years: Kenji Miyazawa, who speaks to us now as if he were among us

still. © RINPOO

This mixture of a deep religious faith and an unstinting scientific methodology applied to all observation is unique in Japanese literature. The two — faith and science — come together in ways the three Semitic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — find hard to reconcile.

Miyazawa believed in the Ten Powers of Buddha. (The ju in the name Kenju is the Chinese character for “10.”) Of the one that he wished most to possess, perhaps it was the first, namely, the power of knowing what is true and what is not. This is the rightful aim of religious practice: Not to impose an abstract construct of faith on reality, but to probe reality and experiment within it, in order to reaffirm one’s faith in the natural cycles of life.

Someone who sees the truth in one era may be branded a fool. In his most famous poem, “Strong in the Rain,” Miyazawa comes out and says that he wants to be someone whom others call “Blockhead.” But that blockhead, or fool, may prove to be a prophet in the future. For Miyazawa, what will happen in the future is inextricably part of what is happening now, and what happened in the past. It is all part of “the monstrous bright accumulation of time.” He, living or dead, or you, or me, or anyone else, experiences this fusion of time, congealed into the present moment from which we look forward and back. To be conscious of all time at once is to be enlightened. Just as everything forms what is the sum in me So do all parts become the sum of everything

This is our key to his thought and how it can help us confront the problems associated with the man-made deterioration of the natural world around us. Violence against another is violence against oneself. Destruction of nature is self-destruction.

The greatest tragedy in Miyazawa’s life was, without a doubt, the death from tuberculosis, at age 24, of his younger sister, Toshiko. (He was two years her elder.) One of the most famous Japanese poems of the 20th century is “The Morning of Last Farewell,” in which Miyazawa describes the journey that his beloved sister will be taking on this day . . . You are truly bidding farewell on this day O my brave little sister Burning up pale white and gentle

He rushes out of the sickroom to fetch her some snow, to cool her fever . . . I now will pray with all my heart That the snow you will eat from these two bowls Will be transformed into heaven’s ice cream

And be offered to you and everyone as material that will be holy On this wish I stake my every happiness

Why is there happiness associated with the death of a loved one whom he cherished, and nursed on her deathbed? Because the very snow that falls “out of pale red clouds cruel and gloomy” is the spirit of the deceased themselves. Our bodies may be lost in death, but our spirit remains as snow, as light, as trees . . . whatever anyone says.

In a number of poems written after Toshiko’s death, Miyazawa envisioned himself communicating with her while exploring nature.

In a beautiful poem titled “If I Cut Through These Woods,” he takes a step into a dark forest and, suddenly, all hell breaks loose: “The fireflies are streaming as never before”; “the wind [is] ceaselessly rocking the trees”; and . . .

The birds, agitated, unable to sleep Are naturally making an awful racket

What’s going on here in these woods? He continues . . . I hear the voice of my dead little sister Coming from the edge of the woods . . . The stars in the southern sky may stream steadily down Yet there is no particular danger here It’s all right to sleep your quiet sleep

He is resigned to his sister’s death because he knows that she is now a part of everything that he sees before him.

I wrote above that, to Miyazawa, all events and phenomena are linked, fused into an instant, whether they are in the past, the present or the future. Miyazawa was also an amateur astronomer and, by the mid-1920s, he had a clear idea of the universe as a space-time continuum. In “If I Cut Through These Woods,” he describes “slivers of [quivering] sky,” and tells us that they are . . . Messengers, so to speak, of a catalogue of light From every possible era that is or ever was

He knows that light from celestial objects comes to us from different eras, depending on how far away from Earth those objects are. This becomes a metaphor for all existence, for we are bound up now in whatever is done on the planet at any time and cannot escape responsibility for it. That Miyazawa sees this as a “catalogue” of light shows that he is intent on ordering these phenomena as best as he can — in order, first, to understand them, and then to use them in the interests of scientific progress.

In fact, Miyazawa spent virtually his entire adult life, short as it was, giving advice, and sometimes money, to the poor farmers of his native Iwate. He taught at Hanamaki Agricultural School, but left teaching at age 30, throwing himself into farming. (The Miyazawas were not farmers. His father was the town pawnbroker.) But his constitution was not up to the hard work, though he desired more than anything else to have his hands “caked, [creaking] with the earth.” Miyazawa was a vegetarian, a rarity even in today’s Japan. He did not believe in the destruction of life. (In his story, “The Restaurant of Many Orders,” the hunters find the tables literally turned on them, as they become the dish served up at this eerie restaurant in the woods.)

Illness struck him in the late 1920s, and this is when he jotted down what has become the most often quoted modern Japanese poem, “Strong in the Rain.” In this poem, he wishes for a robust body so that he can sacrifice himself more perfectly for others.

But it was not to be. In “Night,” he reports that blood has been flowing out of his throat for two hours. Though he is convinced that he is destined for a better place, he is only human now and certainly does not welcome death with equanimity . . .

I have resolved time and again To die alone Unseen tonight by anyone Leading myself by the hand Yet whenever the lukewarm New blood gushes forth Fear, indistinct, white, strikes

This is the dilemma of his faith, and he confronts it head on. Life itself is only a spark set off into the sky at night, and death, a transition to some other realm of being. But the suffering and sadness this realization brings is no less real. One of Miyazawa’s main goals is to teach us how to come to terms with death and what it entails.

When, because of the blood, he cannot speak, he speaks to his doctor silently, with his eyes (“Speaking with the Eyes”), telling him . . . In your eyes I am no doubt a wretched sight

But from here . . . after all All I can see is that clear blue sky And a transparent wind

For Miyazawa, blue is the color that signals passage to the other world. The wind comes from there to blow out the candle flame that is life.

He never married, though being the eldest son in a well-to-do family, and a teacher, he could easily have found a wife; and he is never known to have ever had a romantic liaison. If anything, he saw nature as his lover, and writes this in metaphor after metaphor. As he walks the woods (in his poem, “Ippongino”) . . . My elbows and trousers are smothered In imprints of crescent-moon lips

These imprints are, in fact, left by the leaves of tickweed clinging to his clothes.

In “The Winds are Calling by the Front Door,” the winds urge him to come outside and join them . . . And keep your promise to marry The one among us Who sings in a beautiful soprano voice

This voice belongs to the wind herself.

Despite his religious resignation, and his knowledge of the world as it was in his day — brutally inequitable, selfish and callous in the unrelenting nature of humans — he continued to see himself as a vehicle of change. Many of the characters in his stories sacrifice themselves for the material betterment of others, even going to the extent of climbing up to an active volcano to harness the power in it for the good of all.

This is the kind of “Kenji realism” that speaks to us today. Personal commitment depends upon what he called a “proper” notion of the universe. It pivots on our own actions. It is as far away from fantasy as you can get. All people are faced with concrete choices every day of their lives.

Kenji Miyazawa did not achieve any recognition during his lifetime. Perhaps he is an element in that “catalogue of light” he created; a brilliant spark that is only reaching us 75 years after — as he described death — “the lamp itself is lost.”

Kenji Miyazawa’s collected poems appear in Strong in the Rain (Bloodaxe Books, U.K.), and his most acclaimed novel, Night on the Milky Way Train, appears in a bilingual edition published by Chikuma Bunko and titled Eigo de Yomu Ginga Tetsudo no Yoru. Both books are translated by Roger Pulvers, who this year was given the Miyazawa Kenji Prize in a ceremony on September 22 in Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture.

Roger Pulvers, author, playwright and director, is a Japan Focus associate.

This article appeared in The Japan Times on September 21, 2008.

This compilation of two articles by Roger Pulvers was published at Japan Focus on September 23, 2008.