Roger Pulvers

The scientific term Minakatella longifolia G. Lister may be known only to biologists, but behind the story of this slime mold—and of how specimens came to be kept at the Natural History Museum in London—is the life of one of the most fascinating men of Japan’s modern era: Minakata Kumagusu.

Minakata (right) in Port Saishu

Minakata (right) in Port Saishu

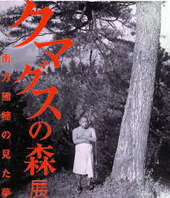

A comprehensive exhibit of Minakata’s legacy in science and art, “Kumagusu’s Forests,” is on show at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art in Aoyama, Tokyo. This exhibit, which closes on Feb. 3, offers a window not only on the life and times of a flamboyant Japanese genius, but also may serve as a guide to the Japanese rediscovery of their rapport with nature.

Let’s start with the most intriguing question: How did a person born in Wakayama in 1867 become a pioneer in his field of biology, recognized as such around the world? This is a time when Japan was barely emerging from 250 years of self-imposed national isolation, a policy that created a scientific and technological gap with the West of immense proportion. And one more question: How could a man like Minakata, eccentric, feisty and volatile to the point of being wild, turn himself into one of the most respected, even worshipped, figures of the Meiji intellectual establishment?

Minakata Kumagusu was born in 1867 as the second son in a family that ran a general store (zakkaya) in Wakayama City. Eventually he would have five siblings. Stories of his intellectual feats as a child are legendary. It is certain that, while in primary school, he did have the ability to throw himself into a task and keep at it for weeks on end. He copied out several lengthy classics, including the 40-chapter Taiheiki, word for word. His early diaries show a marked talent for drawing, both realistic and imaginary. It was when still in primary school that he began making comparisons between Western and Japanese concepts and myths.

In 1884 he entered what is now the University of Tokyo, but unlike two classmates who became famous authors, Natsume Soseki and Masaoka Shiki, he flunked out after two years and returned to Wakayama. In fact, Minakata seemed to have an aversion to university life. Such an aversion did not deter him from his monumental studies of nature, history and art, or from learning foreign languages. Some sources give him credit for mastering 19 languages, but this is no doubt an exaggeration. He probably, however, was proficient in half that many, including, among others, English, which he wrote with near-native fluency, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Latin and Chinese.

In the early Meiji Era (1868-1912), virtually all promise and property fell onto the shoulders of the eldest son. Kumagusu, being the second son, was not specifically tied to his father’s business. In addition, his father, Yahei, admired his son’s amazing intellectual prowess and had not prevented him from moving up to Tokyo to further his education.

Now Kumagusu, back home from Tokyo, was intent on leaving Japan, and this at a time when only the very top echelon of the elite could contemplate such a journey.

On Dec. 12, 1886 he sailed on the steamship “City of Pekin” for the United States, arriving in San Francisco on Jan. 7 of the next year. He did not linger on the West Coast, finding student life at Pacific Business College, which he had entered, tedious. It was to the study of nature, not business, that he wished to dedicate his life. In August of that year he found himself in East Lansing, Michigan, where he gained enrollment into Michigan State School of Agriculture, today’s Michigan State University.

It was while there that he was assaulted, together with a couple of other Japanese young men, by a group of his fellow American students. The American boys were suspended, and that incident seemed to be over; until, that is, the president of the university found Minakata plastered one night in the corridor of his dormitory. The next day he found himself on the road out of East Lansing.

(In fact, Minakata is known to have enjoyed his liquor, going on binges later in life that could last over a week, during which he did not return home.)

His next stop was Ann Arbor, where he joined a group of Japanese students studying at the University of Michigan. His better judgment stayed the hand that might have enrolled him there. It was here that he began writing to William Wirt Calkins (1842-1914), a retired Civil War colonel and serious student of fungi and lichens. Calkins, who traveled often from his native Illinois to Florida to collect fungi, urged Minakata to go to the southern state to pursue mycology as a field of study. Minakata took his advice, arriving in Jacksonville on May 2, 1891. In September of that year he went further south, to Cuba, where he collected fungi and joined a circus. He followed the circus, working in it as the elephant driver’s assistant, to Haiti, Venezuela and Jamaica. I doubt that there is another biologist who collected specimens when not driving an elephant. This circus was truly international, being composed of over 50 white, black and Asian people from Britain, the U.S., France, Italy, China and Japan.

On Sept. 14, 1892, after nearly six years in and about the U.S., he sailed on the British steamship “City of New York,” arriving in Liverpool on the 21st and immediately moving on to London. He notes in his diary: “Settled into an inn at Euston run by Jews and spent the whole first night studying my specimens…. For days, without money, without food, reading….”

It wasn’t long, however, before his presence caught the eye of the illustrious Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826-1897), the first Keeper (i.e. curator) of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography at the British Museum. By 1893, Minakata had published the first of 50 articles in the then popular-science magazine Nature, “The Constellations in the Far East.” He was subsequently to become a regular contributor to the weekly journal, Notes & Queries, an encyclopedia-like journal very widely read in Britain at the time (and, incidentally, still going strong, now as an academic periodical published by Oxford University Press). His more than 300 articles for Notes & Queries range, in their subject matter, from astronomy, biology and zoology to folktales and myths.

Minakata was to spend a total of eight years in London, pursuing his studies and working at the British Museum. After his return to Japan in 1900, he would research slime molds, discovering a new genus, write prodigiously, and become the first truly modern ecologist of Japan, an activist and agitator who fought to protect the environment from just the sort of developers and nationalists who led Japan into the most devastating war in its history.

During his eight years in London, from 1892 to 1900, Minakata lived a hand-to-mouth existence, moving from one dingy rented room to another — even once living above stables on the edge of Kensington Gardens.

Here’s one typical diary entry from the time:

“Penniless, shared a tin of Australian rabbit with guest Takahashi. Cost, one shilling. Big tin and cheap, so buying and eating only this day after day.”

He spent his time mainly at the British Museum cataloging its Oriental collection, and this brought in some money. He also did translation work and dealt in Japanese woodblock prints. His “London Extracts,” comprising 52 volumes, form a fascinating record of life in the British capital at the end of the 19th century. In 1897 he met and befriended the Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen. (He was to meet Sun subsequently again in Wakayama.)

Minakata left England on Sept. 1, 1900, sailing from Liverpool and arriving in Kobe in the early morning of Oct. 15, dressed in what he described as “a Western suit like a mosquito net.”

In his long absence from Japan, his father, Yahei, had died and his elder brother had managed, in a few years, to fritter away virtually the whole of a generous inheritance. In 1906, Minakata married Tamura Matsue, the daughter of a Shinto priest. The next year they had a son; and in 1911, a daughter.

Minakata was soon to throw himself into the study of myxomycetes. Called nenkin in Japanese, these are fungilike slime molds, such as ones he collected in the forests of Wakayama and sent to Guilielma Lister (1860-1949) in London. She named Minakatella longifolia G. Lister after him.

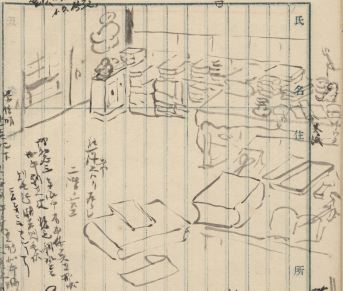

Drawing of Minakata’s room from his diary

Drawing of Minakata’s room from his diary

A word on these intriguing molds. They were thought at the time to be neither plant nor animal, but something else that had characteristics of both. They have an amoeboid phase but are also spore-forming — that is, the amoeboid phase aggregates to form a spore body, and this requires some cellular coordination, making them difficult to classify as either plant or animal. (Minakata was a man attracted to the mysterious and the ambiguous in nature and life.) You may find slime molds quite close to home, growing on wet grass cuttings from your lawn. The Minakata exhibit at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art has many specimens and drawings of slime molds collected by him on display.

The year that he married was a watershed year for Minakata in more ways than one. It was then that the greatest, and most significant, battle of his life began.

In 1906 the Meiji government issued the Edict of the Amalgamation of the Shrines, ordering the dissolution of local shrines around the country and their merger with large, officially sanctioned ones. Minakata saw this clearly, and rightly, as an attempt to politicize the institution of the shrine. In effect, it was an early and giant step toward the establishment of state Shinto, turning the animistic faith into an ideology of nationalism.

To Minakata, local shrines, surrounded by sacred trees, were the symbol of genuine Japanese nature worship. He knew that Wakayama prefectural officials were hand-in-glove with developers (the kind of cozy tieup that exists throughout Japan to this day), and that trees formerly protected by local shrines would be felled in a wholesale manner. He pointed out that this would decrease the bird population for lack of nest sites — and so lead to an increase in the insect population. Farmers would then resort to using insecticides, which in turn would get into the water and harm the livelihood of both freshwater and inshore fishermen.

The result of the merger of the shrines was the formation of a link between the destruction of nature and the eventual creation of a fascist state. Ironically, those who supported that state in Japan’s most disastrous-ever war sang the praises of nature while simultaneously decimating it.

Minakata created a mandala to demonstrate the interconnectedness of all natural phenomena. He wrote of the “three ecologies”: the ecologies of biology, society and the mind. By fusing these three into a world view that necessitated the conservation of nature, he stands as a global pioneer in the ecology movement. His philosophy and actions can teach us a great deal today.

Minakata drawing of three monkeys

Minakata drawing of three monkeys

As for the latter — his actions — they were sometimes, in the thinking of the day, extreme. On Aug. 11, 1910, he barged into a meeting where officials were discussing the “development” of Wakayama timber, threw a portmanteau and a chair at some of them, and protested vehemently against the travesty of destruction they were wreaking on his beloved forests. Fanatic, yes; passionate and committed, absolutely. And where did this agitation opposing the greed and hypocrisy of much “development” get him?

The police were called and Minakata was arrested for “breaking and entering.” In court, however, he was merely handed a suspended sentence; after all, this celebrated native son of Wakayama had brought international renown to his remote prefecture.

He wrote in his diary at the time:

“[The result of the official policy] would have been the laying to waste of every last native forest of Wakayama.”

He was a flamboyant and iconoclastic man who strove to honor what he saw as the nature-harmonious taboos of ancient Japan, embracing them as he embraced his Western learning, as a methodology to husband, preserve and live with nature. He was often seen dressed in no more than a loincloth, carrying a hammer and an insect net, roaming the forests. (Minakata suffered from hyperhidrosis, or excessive sweating, and often pranced about in his natural state.)

Minakata at 45 in 1910. Catalog of Exhibit at the Watari Museum

Minakata at 45 in 1910. Catalog of Exhibit at the Watari Museum

When Emperor Hirohito visited Wakayama in 1929, Minakata was asked to deliver a lecture to him, apparently the first time this privilege was ever afforded a commoner. After the Emperor left, with 110 specimens of slime mold in hand as an offering, Minakata wrote this poem:

Oh breeze from the inlet

Do you realize the branches you are blowing through?

This is a forest praised by the Emperor!

Minakata’s life, from 1867 to 1941 (he died exactly three weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor), spanned the greatest and most dramatic era of change in the last 1,000 years of Japanese history. His “three ecologies” teach us that the fundament of scientific research is a love and respect for nature. To Minakata, what the eye sees, what the mind reasons and what the heart feels are one.

On Minakata’s death, the Emperor, who had led Japan in its most fatal years of “development,” wrote of the island of Kashima in Minakata’s native province of Kishu (Wakayama):

When I gaze upon Kashima Isle, dim in the rain

I think of the man that Kishu gave to the world —

Kumagusu Minakata

Minakata became one of the most heralded heroes of his time. But his greatest achievement may be that he lived his life discovering, protecting and fighting for the phenomena of nature that this country so assiduously and cynically destroyed in his day and has continued to do so since. Minakata is, in this sense, a heroic figure in more ways than one.

This article is slightly revised from a two part feature that appeared in the Japan Times on January 13 and January 20, 2008. Posted at Japan Focus on January 20, 2008.

Roger Pulvers’ latest book in English is Strong in the Rain,a collection of translations of the poetry of Kenji Miyazawa, published by Bloodaxe Books, U.K. Author, playwright and director, Pulvers is a Japan Focus associate. His website is here.