Roger Pulvers

Illustrations Alice Pulvers

Hana York: Though much time has gone by, I can still picture a red down jacket hanging off the severed branch of a tree. It is a cherry blossom tree, and it is in full bloom, but the petals are colorless. The only true color in this picture comes from the jacket, a stroke of red ink hastily brushed on a matted gray and brown canvas.

The jacket belonged to me, and the person standing in the cherry blossom tree’s shade is my father, Nicholas York. He is absolutely still, a statue of his own invention.

You see, my daddy is a spulc-tor. I can’t pronounce that word very well even now, but I know what it is because I have often seen him making his little statues of people out of clay. I think there will be many spulc-tors in the world because all the little children at my kindergarten also made statues out of clay like daddy’s.

There is another person not far away. She is my mummy, Setsuko York, and she is at the very edge of the picture. Daddy doesn’t know she’s there just yet. But first let me tell you how they happened to be there.

The cherry blossom tree stands in front of my kindergarten. Mrs. Katayama has been running it for so long that three generations of people in the neighborhood had gone there.

The person who takes me to kindergarten and picks me up every day is daddy. That’s because mummy works at the Isetan Department Store in Shinjuku in the middle of Tokyo and doesn’t get home in time. In fact, most of the time she doesn’t get home at all until very late at night, and daddy is the one who shops and cooks dinner for me. It’s all right, because the only other thing he does is make his statues out of clay, and that doesn’t really seem to take up so much time.

Daddy definitely worries too much. He worries that I won’t finish my toast and jam and that I won’t wear my red jacket when there is a chill in the air. I tell him I’m not cold, but it doesn’t do much good.

He says that it’s still early spring and that means it’s cold. You see, my daddy is Irish. I guess it’s cold in spring in Ireland, because he can’t seem to get used to being here.

So, even though I won’t wear the jacket myself, I let him carry it for me. Then he takes it home on the train and brings it back to the kindergarten in the afternoon. Every time I think about daddy now, I see him clutching onto my red down jacket in front of the kindergarten. He is surrounded by Japanese mummies and he bows to them, which looks really funny because he is at least a head taller than all of them.

Nicholas York: Hana is constantly criticizing me. Imagine being criticized by a 5-year-old. She never seems to be satisfied with anything.

“My bath ready, daddy?” is the first thing she says after walking through the door and throwing her cap on the floor. I got her into the habit of taking an early bath. When she’s finished, she walks through the kitchen with wet feet, a large towel around her body and a smaller one propping up her hair.

“The bath is filthy, daddy,” she says. “You will have to clean it before mummy comes home.”

By 9 o’clock, when she is in bed, I can sit myself down at my table and get to work. Setsuko usually comes home by 10. I wait for her to eat dinner, or, if I am lost in my statues, I do not eat at all.

Hana: When my mummy returns home from work she comes into my bedroom without putting her handbag down and stares at me in my bed. Sometimes I sit up and see both my parents staring at me as if I were a strange animal in a zoo. They are not talking to each other. In fact, they rarely talk to each other.

One night I asked them, “Why are you staring at me like that?”

“Because I heard you scream,” said my mummy.

“Scream? I didn’t scream.”

I look at my daddy’s hands. There is a big lump of clay sticking off the top of his index finger like a nose on a clown. It really makes me laugh.

My parents look at each other. They can’t understand why I am laughing.

Without saying anything, mummy leaves my room. I can hear her making herself a cup of coffee in the kitchen. Daddy kisses my forehead, tucks me in and smiles at me.

Daddy won a prize a few years ago, before I was born, for his spulc-ture. But now no one wants to buy it. I know that he is not happy, but he says he is happy because of me. It’s not enough to be happy because of me.

Nicholas York: Setsuko usually doesn’t go to the store on Wednesdays, but that week there was a special meeting concerning the remodeling of the eighth floor. We dropped Hana off at the home of a friend, Yuriko Sakagami, a single mother with three small children of her own. Yuriko was to take them all, including Hana, to Tama Zoo.

It happened when I was giving a lecture, which I did once a year, at a private art school near Omotesando Station in a swish part of town where all the “brand” shops are gathered.

The lecture was about the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Giacometti’s people were not formed by being built from nothing. They were scraped and cut, denuded of all their outer covering and left to stand by themselves. In an instant, with even a single soft touch of a hand, they would fall to the ground and shatter.

Mr. Hashizume, head of the school, rushed into the lecture hall. I was standing in the glare of the projector on the screen, a picture of one of Giacometti’s thin striding figures across my face. Squinting at Mr. Hashizume, the only thing I noticed was his gaping mouth.

“Mister York!” he shouted.

That was all, just my name. Every eye in the lecture hall was on me, starkly exposed in front of the screen.

Yukiko Sakagami had been leading the four children on the pavement alongside a busy road, walking quickly to catch the bus, when her 3-year-old son, Hiroyuki, wandered into the street. Hana ran after him. A car with two young men in it could not stop in time. Traffic came to an immediate halt and an ambulance arrived minutes later, but Hana had been instantly killed by the car with the two young men in it.

“I’m what Japanese people call a ‘half,’ aren’t I, daddy?” she had once asked me.

“Yes you are, petal.”

“Which half am I, daddy?”

Hana: I had only a split second to see the front of the car that was speeding alongside the bus. The passenger was a young man, probably about three times my age. I think he saw me before the driver did. The driver of the car had his head down. I think he was reaching for something that had fallen down, maybe a mobile phone. All I could see was the black hair on the top of his head. Suddenly he raised his head and I saw that he had wraparound sunglasses on and he was smoking a cigarette. Those were the last things I remember seeing.

The front bumper of the car hit my stomach, and I must have slumped forward because before I was knocked back I felt the hot grill of the car hit my face. The back of my skull smashed into the street and I heard a very loud CRACK! I don’t know why, but I rolled over onto my stomach against the curb as the left front tire drove over my back. My entire body was crushed by this. The bones in my back and my ribs were not so hard, seeing as I was only 5 years old, and my thin body was now flat, bloody but without dimension.

Setsuko York: Two years have passed since Hana’s death, and Nick is still not himself. At night I barely see him leave the second bedroom that he had converted into an atelier. He sleeps there, too. After he falls asleep, sometimes at his table, I peek in. All of his statues are very small, no bigger than a child’s hand. His figures are thinner than a chopstick. They stand still, leaning forward on a slight angle, as if readying themselves to walk forward but unable to do so.

A couple of months ago I convinced him to take a short holiday with me to France. On the Narita Express back from the airport to Tokyo after our return, I put my arm through his and leaned my head on his shoulder. I told him that we were still young and that I wanted to have another baby. He was holding the digital camera in front of his face, clicking through one photo after another from our trip.

He just stared at the photos like that without so much as looking at me.

I am much less busy at the department store now, and, thanks to Mr. Hashizume, Nick is teaching full time at the art school. He is constantly being given presents by his students, some of whom are much older than he is. They tell him that he has changed the way they look at art and life.

I would gladly take a long leave from work, or even quit, if it meant that I could get pregnant again.

Last Wednesday morning, Mr. Hashizume phoned me at home. Apparently Nick had not yet arrived at the school.

“The train must have broken down,” I said. “Nick always leaves long before time.”

“But he is often late for work, Mrs. York,” said Mr. Hashizume. “And there have been the odd days when he has not showed up at all. He’s so popular here, people don’t seem to mind. But, well . . . I really never wanted to have to tell you this.”

That night I made Nick an Irish stew with soda bread and bought a six-pack of Guinness. It was a cold early April day and I thought he would be pleased. But he flew into a rage when I mentioned the phone call to him, telling me in an unusually strong Irish accent to “mind my own business.”

“You have your job and I have mine, right?” he said. “Let’s leave it at that, shall we?”

He went into his atelier and I heard the sound of a lump of clay being hurled against the wall with great force. I had never seen Nick lose his temper in the past.

I stood in the doorway. “Nick, please,” I said. But all he did was stare down at one of his statues, picking little pieces of clay off it and rolling them between his fingers.

Hana: It was one year after this that the picture of my father and mother by the tree came into being.

During that one year, my father went back to sleeping in the same bed as my mother. I could see them clearly, every minute of the day and night. It was a few minutes after 3.00 and he was awake, peering into her face. She was breathing steadily, her eyeballs not moving below her lids. What is preventing me from reaching out and touching her, he thought. Her black hair had fallen over her face, her breath brushing through it, then drawing it into her mouth, a few strands caught between her lips, her tongue licking them out of instinct, trying to force them out. He wanted so much to push aside those strands of hair, but something was staying his hand.

The next morning he left as usual, carrying his briefcase. My mother didn’t know what he had inside it, though. She assumed that it would be his computer and his materials for teaching his art class.

She decided to follow him. Perhaps he was seeing another woman. After all, my father and mother have been cold to each other in the three years since my death.

Setsuko: I followed Nick onto the train. Instead of going all the way to Shinjuku Station, he got off at Kyodo. That is the station closest to Hana’s kindergarten. But why would he be going there?

Nick: I remember the night Hana was born. I left the hospital and went racing down the street. It was close to midnight. I passed by a police box. The policeman was seated at his desk under a yellow light. He looked up just as I dashed by, and I shouted, “Akachan ga umareta! (A baby’s been born!)”

The policeman jumped up and yelled, “Doko da?! (Where?!)”

I had never been so happy in my entire life.

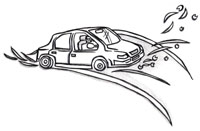

There is a light snow falling now, as if slipping off a plate of gray that is the sky. No need to worry about meeting anybody I recognize at the kindergarten. All the children who were there with Hana have left now. Different children, different parents. Same tree though, with its petals filling every space above my head. That very same tree will be there.

I turn the corner where the kindergarten is, but suddenly I am stopped in my tracks. I stop so abruptly that I almost lose my balance and fall onto my face. I hold my briefcase tightly to my chest.

A little girl with a red ribbon in her hair has come out of nowhere, on a bicycle, into my path. One more step and I surely would have collided with her. She screeches to a stop and looks up at me, smiling.

“Gomen ne,” she says. “I’m sorry.” Then she faces forward again and rides away, as if it never happened.

For an instant I could not move from that spot, but I managed to take a single step forward, then another and another, walking with great difficulty, toward Hana’s old kindergarten.

I look at the little children lining up beside the concrete animals and the swings in the yard. I can see this tree, with me under it, reflected in the sliding glass doors of the main building.

Just then, a teacher standing on the verandah catches my eye and bows to me, keeping her head down for a long time. She has recognized me as Hana’s father. A gust of wind blows some petals in front of my face and sends them scuttering along the ground. The little children are all inside the building now, singing a song.

Setsuko: The mothers were gone. I am standing beside a wall, half hidden from view, not far from Nick.

He is now stepping around the trunk of the tree, back and forth, as if quietly dancing under the cherry blossoms. Then he kneels down and opens his briefcase. He takes Hana’s red down jacket out of it. I haven’t seen that jacket in more than three years. Where has he been keeping it?

Nick put Hana’s jacket over a severed branch and gradually moved his hands away from it, as if fully expecting it to fall once he stopped holding onto it.

At that moment our eyes met. He didn’t act surprised to see me there. Neither of us could move. It was as if our legs were anchored to the ground where we stood.

I cannot remember how long it was we remained like that. All I know is that it seemed like an age.

Hana: Not too long after that, Nick and Setsuko made a trip to Kyoto, where they’d met exactly 10 years before. They revisited all of the old places they had been to when they had first fallen in love — and they even took lots of new pictures of themselves at all those spots. Pictures on the bridge, pictures by the river or sitting in silence on the edge of a temple garden.

Nine months later, Setsuko gave birth to a beautiful baby girl. They named her Haruko. When I think of her, which is a lot, it occurs to me that dying isn’t really the end of everything, and that Nick and Setsuko’s new daughter is every bit as beautiful as I was — and, to be perfectly truthful about it, maybe even more.

This story was published in The Japan Times on December 30, 2007 and at Japan Focus on December 30, 2007.

Roger Pulvers’ latest book in English is Strong in the Rain,a collection of translations of the poetry of Kenji Miyazawa, published by Bloodaxe Books, U.K. He is a Japan Focus associate. His website is here.

Alice Pulvers is a young Australian artist and illustrator living in Sydney. She was born and raised in Japan.