Richard H. Minear, in conversation with Mark Selden

Charles Pellegrino’s The Last Train from Hiroshima (Henry Holt, 2010)1 came highly touted. Its special claim to fame seemed to be its scientific background. The jacket identified the author as someone who “has contributed articles to many scientific journals based on his work in paleobiology, nuclear propulsion systems for space exploration, and forensic archaeology.” A blurb from a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History (he is an associate professor of biology at C.W. Post Campus of Long Island University) praises the “scientist’s eye for detail” that Pellegrino exhibits. The reviewer in the New York Times wrote: “He pays particular attention to forensic detail, and provides a slow-motion, almost instant-by-instant explanation of how the atom bomb discharged its fury.”2 The reviewer for the Washington Post wrote: Pellegrino “lets cool, scientific description produce its own shock effects. He shows us the physics of atomic destruction. It may be that what makes Hiroshima so horrifying is seeing human beings reduced to bare elements, death a matter of chemicals, not consciousness. Pellegrino describes what happens inside: iron separating from blood, an atomic refinery, bones becoming incandescent, marrow boiling away, soft tissue dissolving in Ebola-like bleeding.”3

Despite all this cheerleading, Last Train is a train wreck. The first sign of trouble came from U.S. airmen on the Hiroshima and Nagasaki missions; they charged that Pellegrino informant Joseph Fuoco, who claimed to have been a last-minute replacement on the Hiroshima mission, flew on neither mission.4 Then came questions about Pellegrino’s story that a civilian weapons specialist died of radiation on Tinian the night before the mission and about his assertion that the Hiroshima bomb was a “dud.”5 Then came the news that Pellegrino’s claim to have a Ph. D. from Victoria University in New Zealand was false.6 The publisher has now withdrawn the book from the bookstores “due to the discovery of a dishonest sources [sic] of information for the book. It is easy to understand how even the most diligent author could be duped by a source, but we also understand that opens that book to very detailed scrutiny. The author of any work of non-fiction must stand behind its content. We must rely on our authors to answer questions that may arise as to the accuracy of their work and reliability of their sources. Unfortunately, Mr. Pellegrino was not able to answer the additional questions that have arisen about his book to our satisfaction.”7

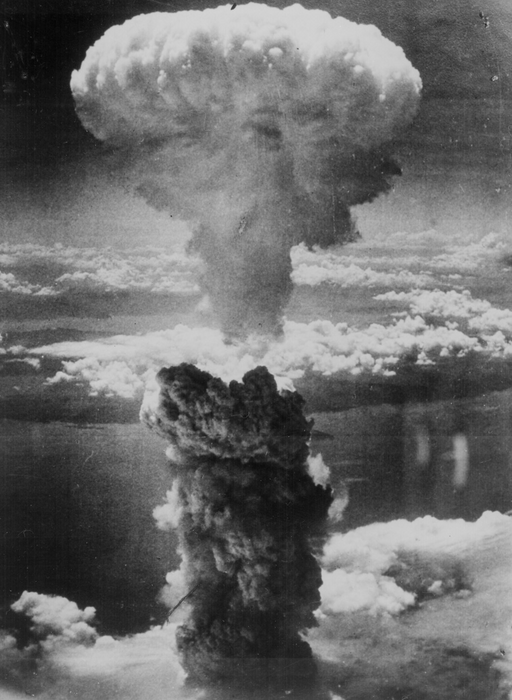

Mushroom cloud over Nagasaki: the iconic official image of the bomb from 60,000 feet

What follows is only occasionally a critique of Pellegrino’s book. It is more fundamentally a consideration of the state of Hiroshima studies today: what we have, what we need, what—if anything—we can do to protect ourselves from the Pellegrinos of this world and the media that accept their claims.

|

Nagasaki from the ground, August 10, 1945. |

Mark Selden Comment #1: The issues of truth and accuracy are critically important for every non-fiction work, which is what Last Train purports to be. They are equally important for the credibility of the author and the press. It is worth noting, however, that the “facts” whose abuse apparently most angered readers, commentators and interviewees, centered on questions such as the identity of the flight crew and the claim that a nuclear accident occurred prior to the Hiroshima mission. That discussion has detracted from understanding and debate on the central issues of Hiroshima and the atomic bomb that define the nuclear age in which we live. These questions include the nature and impact of the atomic bombs on the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the ethics of bombing civilians; assessment of the atomic bombing and firebombing that annihilated sixty-four Japanese cities. These issues can be explored through discussion of truth and fiction in Last Train in light of the vast literature on the bomb, including the documentary and fictional accounts of survivors, and the historical literature assessing the bomb.

Fact and fiction: how important is the distinction? What is the role of survivors? What is the role of historical novelists? What is the role of documentary film? Of Hollywood film? Of science? These are questions not at all specific to Hiroshima. Treatments of the European holocaust have spawned a similar debate: consider only William Styron’s novel Sophie’s Choice (National Book Award for Fiction, 1980; leading actress Oscar for Meryl Streep in 1982) and Roberto Benigni’s film Life is Beautiful (winner of three Oscars in 1998).

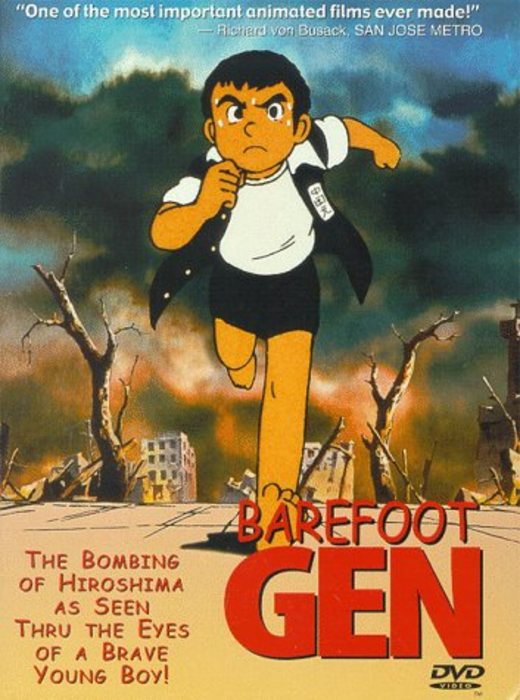

We have in English a wealth of accounts about the Manhattan Project and the building of the bomb and the scientists who participated. We have a wealth of books assessing the military situation in summer 1945 and the policy decision—if there was one—to drop the bomb. We have available in English a wealth of accounts including survivor accounts. These include John Hersey’s early—and still widely read—Hiroshima (1946). We have the writings of Hara Tamiki and Kurihara Sadako and Ōta Yōko and Tōge Sankichi.8 There are volumes of poetry and photographs. There are as well a considerable number of artistic and literary attempts by non-survivors: Ōe Kenzaburō’s Hiroshima Notes; Ibuse Masuji’s Black Rain; After Apocalypse: Four Japanese Plays of Hiroshima, which features both hibakusha and non-hibakusha playwrights.9 There are collections of short stories—by survivors and non-survivors: The Crazy Iris and Other Stories of the Atomic Aftermath; The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.10 There is Hachiya Michihiko’s Hiroshima Diary. There is Barefoot Gen; we will soon have Nakazawa Keiji’s prose autobiography.11

There is also the massive Hiroshima and Nagasaki: the Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings (tr. Eisei Ishikawa and David L. Swain, 1981).12 There are books on memory and public history. There are books about Hiroshima literature.13 (Of the above titles, only Hersey’s Hiroshima makes it into Pellegrino’s “Selected Bibliography”—with the author’s name misspelled “Hershey.”) What should the balance be between the science/policy issues and the human issues? Let me explore some of these issues in the context of discussing the Pellegrino fraud.

Pellegrino flaunts his scientific background and interests. The vast majority of the entries in his “Selected Bibliography”—30 of 36 items14—are narrowly scientific treatments: “Atomic Bomb Surface Burns: Some Clinical Observations Among Prisoners of War Rescued at Nagasaki,” “Malignant Neoplasms Among A-Bomb Survivors: Study of 114 Autopsy Cases, 1957-1972,” “Radiation Sickness in Nagasaki: Preliminary Report.” (Conspicuous by their absence are treatments of the science of the bomb, such as the books of Richard Rhodes, Francis Gosling, Peter Hales, Robert Serber, William Lanouette.) It is enough to intimidate the non-scientist. Indeed, that may be its role. Like the bibliographies Michael Crichton appends to his contentious novels, this “Selected Bibliography” may have the goal of of lending a pseudo-academic patina and scaring off would-be critics.15

That technical scientific literature plays little role in Pellegrino’s narrative.16 He does speak in the early pages of what happens in the first nanoseconds: “From the moment the rays began to pass through [Mrs. Aoyama’s] bones, her marrow would begin vibrating at more than five times the boiling point of water. The bones themselves would become instantly incandescent…” (3). Or: “Within the core of the reaction zone, approximately 560 grams (or 1.2 pounds) of uranium 235 began to undergo fission before the compressive, shotgun-like forces designed to start the reaction, and to hold it together briefly, were overwhelmed by forces pushing it apart. Three times heavier than gold (at the moment of compression), every ounce of the silvery, neutron-emitting uranium metal occupied three times less volume than gold” (4). Or: “One ten-millionth of a second later, a sphere of gamma rays, escaping the core at light speed, reached a radius of 33 meters (108 feet) with a secondary spray of neutrons following not very far behind” (5). But the vast bulk of his book is about the survivors (of which more below).

The science seems compelling. Here is Mark Selden’s initial reflection on the science: “Among the arresting things about the book, which is extraordinarily effective in building drama and carrying the reader along, is the scientific treatment of human suffering, of the factors divide the living from the dead. This differentiates it from some other accounts. This could be an area of strength: maybe Pellegrino really understands the physics of who lives and who dies in relationship to positioning. Or is it possible that he also makes much of this up? He does cite a specialist literature that few historians and literary types like us have looked at much.”

I will have to leave most questions about scientific accuracy to others, but answers are already beginning to come in. From Alan Carr, Laboratory Historian at Los Alamos National Laboratory:

I have not had the opportunity to read Mr. Pellegrino’s book…in its entirety. However, I am familiar with the book’s treatment of the Hiroshima strike and the events leading up to that fateful event. Chapter Four, “And the Rest Were Neutrinos,” reads more like a technically dubious piece of fiction than a historical rendering of actual events. For instance, Mr. Pellegrino alleges a fatal accident occurred on Tinian during the assembly of Little Boy. Such an accident never occurred. Mr. Pellegrino also claims Little Boy was a “dud” (64). It was not. The assembly and delivery of Little Boy were accomplished without incident. Little Boy achieved a yield of approximately 15 kt [kilotons], and served as the basis for future nuclear weapons designs. Mr. Pellegrino’s assertion that the uranium gun-assembled weapon was “prone to accidental fission” could not be further from the truth (65). There is no documentation, unclassified or classified, which supports Pellegrino’s claims pertaining to Little Boy’s preparation for and performance in combat.

Mark Selden Comment #2: To address the issues of scientific assessment I consulted Richard L Garwin, a University of Chicago-trained physicist who worked in the lab of Enrico Fermi, was the author of the design used in the hydrogen bomb (1952), and is a recipient of the National Medal of Science, the nation’s highest honorary science and engineering degree.17 Garwin’s response to Pellegrino claims quoted above are telling (personal communication, Richard Garwin to Mark Selden, April 5, 2010).

Pellegrino places Mrs. Aoyama in her garden just below Point Zero when the bomb fell. Garwin comments of Pellegrino’s account of her bone marrow vibrating at more than five times the boiling point of water:

“If she was at the epicenter, then the bomb’s energy of 10**14 J of which about 1% was liberated in the form of radiation– so10**12 J would be spread over an area of about 30 billion sq cm, so that there would be about 30 J/sq cm. This would be absorbed typically in a distance of 10 cm in tissue, corresponding to a deposition of energy of about 3 J/cc. This would be enough to raise the temperature of the tissue by about 0.8 degree centigrade.“

In short, Pellegrino’s calculation, or perhaps fictional dramatization, took the horror of the experience of the bomb’s victims at Ground Zero and contrived a scientific-medical explanation that bore no relationship to the physics.

On the question of gamma rays and neutrinos, Garwin responds tellingly:

“. . . it is true that the sphere of gamma rays does escape the core at light speed and in a ten millionth of a second reaches a radius of about 30 meters.

As for the neutrons, there are no “heavy ions” associated with the neutrons, and the neutrons are pretty much stopped in less than a meter of material, whether it is flesh or soil or bedrock.

Neutrinos come not with the gamma rays but typically a measurable fraction of a second later from the beta decay of the fission products. Neutrinos travel at the speed of light, but there is not a significant number of neutrinos 1.24 milliseconds after detonation, even at Hiroshima. What is true is that the time required for neutrinos to traverse the 13,000 km diameter of the Earth is 40 milliseconds, and not “1.24 milliseconds”. So both the physics and the arithmetic are greatly in error in this passage.”

Again, Garwin shows that Pellegrino’s calculations lack scientific foundation.

To Carr’s comment I can add one wild mistake that anyone with a globe can easily verify. Pellegrino writes (39) of one victim, Hirata Setsuko, who was directly beneath the explosion, at Ground Zero:

Fast neutrons and heavy ions came down through tiles and roof beams and either stopped inside her body or kept going until stopped by several hundred meters of solid bedrock. Neutrinos also descended through the roof… They continued through Setsuko without noticing her, then traveled with the same quantum indifference through the earth itself. The very same neutrinos that passed through Setsuko sprayed up toward interstellar space a few hundred kilometers west of Brazil. When Setsuko’s neutrino spray erupted unseen, just off the coast of Ecuador, 1.24 milliseconds after detonation, she was still alive.

Pellegrino may be right about the behavior of neutrinos. [As Garwin’s comments indicate, however, that is not the case.] But his geography is laughably off. A straight line from Hiroshima through the center of the earth winds up nowhere near Ecuador but across the South American continent and over 6,000 kilometers to the south—in the South Atlantic in the vicinity of the Falkland Islands.18

Many of us concerned with Hiroshima are humanists, ethicists, and social scientists—historians, specialists in Japanese literature and society. We tend not to deal in nanoseconds and neutrinos. Should we? Should we be embarrassed because we don’t? Does Pellegrino make the case that this level of science is an essential part of the picture even for non-scientists? I think not. Indeed, focusing on the technical may be a way to avoid confronting the human and moral issues.

Consider, for a moment, a case with some clear parallels to Hiroshima: the European holocaust.19 When we teach the European holocaust, we set it in many contexts: history, technology, and war. We don’t begin or end with survivor experiences, but survivor accounts— Anne Frank, Elie Wiesel, Charlotte Delbo, Nelly Sachs, Paul Celan—play a critical role. But how would experts on the European holocaust react to a treatment that discusses, nanosecond by nanosecond, the effects of Zyklon B on the respiratory system of a specific victim—Anne Frank, say, had she not died of typhus? Is this helpful knowledge or scientific obscurantism?20

I submit that this level of supposed scientific accuracy is absurd. The issue isn’t—shouldn’t be—the specific effects of an atomic bomb on specific human bodies at this nanosecond/microscopic level. With poetry and prose and art and photography, we document the agony of individuals, named and anonymous, but pseudo-scientific exactitude of the sort Pellegrino purports to offer gains us nothing.

Mark Selden Comment #3: I would frame this differently. The specifics of the experiences of victims, whether holocaust or Hiroshima, comfort women, or Nanjing massacre victims convey, better than almost anything else to many students and readers the power of the experiences. This is why people teach the novels that you and others have translated, why they teach Barefoot Gen, why they use some of the poetry written by victims with its precise images of life and death, why they use the Maruki Hiroshima murals, horrifying as some of them are. I believe the proper point to be made is that the record of individual experiences, whether as bio or autobiography, film, manga, photography, vital as it is, is insufficient if the goal is to grasp the significance of these events: it is essential to open questions that lead to understanding of historical, legal, and ethical frameworks. It is appropriate that historians, political scientists, literary critics, artists, writers, etc. and, yes, scientists, will offer different, perhaps complementary framings of those larger issues are. An ideal pedagogical situation would be one in which their multiple perspectives could be brought into conversation.

|

Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, from their Hiroshima murals series |

Fact and fiction: how important is the distinction in the realm of human meaning of the atomic bomb?

Mark Selden Comment #4: Here you raise a key methodological question. But in my opinion, you never address the big issue . . . moving on instead to get at Pellegrino’s abuses. I believe that you and I hold the view that fiction and documentary fiction can convey large meanings concerning human experience . . . sometimes better than ‘historical facts’ or supplement historical treatments. Nevertheless, it is essential that we scrutinize fiction carefully, just as we scrutinize and assess historical documents. But it is necessary to discuss this. Why should we turn to fiction, or poetry, or photography, or art?

Much of Pellegrino’s content comes from a small number of existing sources in translation, especially Akizuki Tatsuichirō, Hachiya Michihiko, and Nagai Takashi; according to Pellegrino’s index, each of these sources appears on approximately forty pages. Indeed, Pellegrino cites them more than he cites any of his interviewees. But how reliable are Pellegrino’s citations of the translated Japanese sources?21 In an extended passage, he has Hachiya Michihiko sensing the Nagasaki blast as it takes place (152):

Why, he wondered, did he feel as if a spectral hand had suddenly reached out and shaken him awake? Dr. Hachiya did not believe in the motility [sic] of consciousness…and yet, for an instant, a bone-chilling sense of dread stole into him.… Then, from 183 miles away in the south, a low rumbling roar reverberated through the heavens, building to a loud crack that definitely was not the sound of an earthquake. Hachiya drew a deep breath, held it wistfully, and expelled it in a sigh.

In fact, Hachiya mentions Nagasaki only once, on August 11 (48): “Later in the day news came that a mysterious new weapon had been used to bomb Nagasaki with the same result as in Hiroshima. It, too, had produced a bright flash and a loud sound.”

In another passage (230ff.), he segues from Hachiya to Barefoot Gen to the Hiroshima poet Kurihara Sadako. In the ruins of the Communications Hospital, Hachiya hides from approaching planes, then realizes there is “simply nothing left in Hiroshima worth bombing.” This passage from Hiroshima Diary is on August 14 (and does not include the reflection that Hiroshima has nothing left to bomb). Then after a paragraph break comes this sentence: “In a lean-to beyond the hospital, Barefoot Gen’s baby sister had ceased crying and, strangest of all, had begun refusing her mother’s milk.” “Beyond the hospital” for the Barefoot Gen lean-to is a real stretch: the distance between the hospital and the spot “Gen” and his baby sister first found refuge is roughly five kilometers, all the way across the city. Moreover, nourishment was a problem not because the baby refused to drink but because the baby’s mother produced no milk (the baby’s death from malnutrition occurred four full months later). Then segue to Kurihara: “Less than a kilometer away, a thirty-two-year-old poet named Kurihara was asking the same questions as she carried from the foundations of her home a radioactive memento of human bone fragments stuck together like candies in melted glass. … She thought of the emperor’s red and white flag—which up until now had represented the Rising Sun. But presently, the red of the Rising Sun became people’s blood, and its background of white became people’s bones.” Kurihara’s home was at least three kilometers north of Hachiya’s hospital, and the blood/bones imagery is from a poem she wrote twenty years later, in 1975. Pellegrino’s account is a mishmash: invented words, telescoped connections, collapsed chronologies.

|

Drawing by a survivor of the bomb recalling the hand of a victim |

Mark Selden Comment #5: On close inspection, the attempt to create verisimilitude through precise factual statements undermines the author’s credibility. By contrast, the detailed treatments of the human consequences of the atomic bombing in the novels and poems discussed briefly above convey with great power and awe the human experiences of individual hibakusha, and the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In playing fast and loose with the facts, conflating distances across the city, ignoring distinctions between historical figures and literary creations, we see Pellegrino at work on the future film score. What is striking about all of these examples, however, is that none appear to add any deeper understanding of the human toll of the atomic bomb than either the documentary accounts, such as those of Dr. Hachiya, or the many literary accounts such as those of survivors like Ōta Yōko, Hara Tamiki or Hayashi Kyōko, or other authors such as Ibuse Masuji or Ōe Kenzaburō. Far from it. At the same time, his pseudo-science undermines the credibility of the entire work. In the end, book readers are likely to remember Last Train for the author’s fraudulence. But the book’s flaws run deeper. For all its ability to dramatize a story through close attention to a handful of hibakusha (real and imagined) Pellegrino never elevates his account to draw the attention of readers to the largest issues posed by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: these are, first, the continuing controversy over the decision to use the atomic bomb against the citizens of two cities and its significance in ending the war; and, second, the human consequences of the use of atomic weapons and hence the significance for the future of war in the atomic age.

Like Spiegelman’s Maus, Barefoot Gen is an artistic representation of reality. Compare Barefoot Gen and Nakazawa Keiji’s autobiography, and numerous contrasts emerge. Nakazawa himself has pointed to one important one, that he was not present at the deaths on August 6 of his father, older sister, and younger brother.22 Before embarking on Barefoot Gen, Nakazawa had drawn a series of stories set in post-bomb Hiroshima, and to sustain the 2,500 pages of Barefoot Gen, he invented sub-plots. One example is the character Kondō Ryūta, who appears nowhere in the autobiography. Astonishingly, Pellegrino treats Ryūta as a real person, including him, for example, in his appendix “The People” (325): “A five-year-old Hiroshima orphan, unofficially adopted into the family of Keiji ‘Gen’ Nakazawa. He lived in the same neighborhood as Dr. Hachiya.” It’s as if a historian of the European holocaust were to treat one of the characters in Spiegelman’s Maus as a real person.23 And once again, Pellegrino telescopes a connection—an imagined connection, at that!

|

Nakazawa Keiji (Barefoot Gen) fleeing the bomb |

But fact and fiction? Is fiction impossible? Was Adorno right, “After Auschwitz no poetry”? Or is it perhaps the case that fiction—undisguised, honest fiction—has a major role to play? Who would prefer to do without Maus or Barefoot Gen or Black Rain? Barefoot Gen may be partly fictional yet still have more impact than a strictly factual treatment; it may come closer to conveying the human truth of the atomic experience. And it has reached generations of folks left untouched by other accounts of Hiroshima.

|

Barefoot Gen, the film |

Ibuse Masuji’s Black Rain is a non-survivor novelist’s rethinking of Hiroshima; its impact has been enormous. Hara Tamiki’s Summer Flowers is based closely on his own experience, yet his temperament and style shaped the account in important ways; its impact on students is invariably powerful. Perhaps what we’re after in the end is authenticity—the honesty of a survivor’s testimony, the honesty of a non-survivor artist in making Hiroshima her subject matter. Fiction permits invention.

Does Pellegrino succeed in making characters real? Readers will draw their own conclusions. My own judgment is that he does not. Compared with the classics of Hiroshima literature—Ōta and Hara and Tōge and Kurihara, compared even with John Hersey’s Hiroshima,24 about which I have the gravest reservations, Last Train does not offer a compelling vision of what happened on the ground.

Mark Selden Comment #6: The question remains: why were so many reviewers and readers deeply impressed by Pellegrino’s account, only to feel deeply cheated when revelations appeared that undercut many of his boldest claims? The reasons certainly include his narrative gift and filmic impulses. The conception of tracking survivors of the Hiroshima bomb who made their way home to Nagasaki only to be bombed again, was a cinematic vision that rested on a small number of actual cases. Pellegrino is in fact a skilled screenwriter in the sense of being able to conjure powerful, even compelling images, at times at the expense of the historical record. Last Train reveals why reviewers and readers need to be on their guard, perhaps especially so when the writing is gripping. Fortunately, the literature of the bomb, including both the primary and secondary literatures, abound with authentic texts, some of which are even more riveting.

I am reminded of Marjorie Perloff’s reaction to an earlier Hiroshima fraud, the poetry of “Araki Yasusada”—a non-existent hibakusha poet dreamed up by Kent Johnson. She concluded her lengthy critique with the hope that “‘Yasusada’ may prompt us to familiarize ourselves with the actual Hiroshima memoirs of the fifties and sixties, as well as…Japanese postwar poetry in its specific articulations. What we need are not more ‘authentic’ and ‘sensitive’ witnesses to what we take to be exotic cultural and ethnic practices, but a willingness, on the part of poet as well as reader, to look searchingly and critically at what is always already there.”25 Many compelling survivor accounts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been told (and translated). We need most of all to deal with them, not with the fevered imagination of someone like Pellegrino.

Consider here the comment on Amazon.com of Thomas J. Frieling of the University of Georgia:

My problem is the fact that this book got positive reviews in the mainstream press (including the NYT). I have to ask—what has gone wrong with the process of reviewing books? And backing up one step—what’s gone wrong with the publishing industry that allows error-riddled books to pass muster? Doesn’t the publishing industry employ copy editors and fact-checkers any more?

And who gets selected to review books like this—reviewers who obviously aren’t qualified to pass judgment on the book’s quality or accuracy? Where are the experts who could vouch for a book’s accuracy–why aren’t they being sought out to review books about which they are recognized subject experts? It should be a scandal.26

Henry Holt and the New York Times—even James Cameron—need not look far to find genuine Hiroshima experts, genuine survivor accounts. They can go to the catalog of any major library or spend ten minutes searching on the web. That they don’t is a function of many factors, including the economics of publishing today.

Mark Selden Comment #7: The incident reveals that this major publisher has no policy of external or expert review. It relied instead on its own in-house editor, John Macrae, who reports having had 250 questions about the manuscript but considered it sufficient to raise them with the author. Motoko Rich, “Pondering Good Faith in Publishing,” presents Macrae’s comments. This is an approach that perhaps augurs well for sales (barring an implosion such as this one), but it alerts us to one of the reasons for the lack of rigor, indeed, the numerous abuses in the present manuscript. The Pellegrino affair would serve a useful purpose if it inspired discussion about the review processes, or lack thereof, of some major commercial publishers. The failures are particularly glaring in this case given the vast literature on all aspects of the atomic bomb and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki experiences and knowledgeable authors whose wisdom could have helped avert this train wreck.

American textbook treatments of Hiroshima since World War II, the fiasco at the Smithsonian in 1995 when political pressure prevented both questioning the Hiroshima decision and reflecting on the human impact of the bomb,27 the decision of the Obama Administration in Spring 2010 against adopting a “no first use” policy: these are all different facets of the same phenomenon—denial. Even sixty-five years after Hiroshima, we refuse to face the reality of nuclear war. Pellegrino’s Fuoco claimed, falsely, to have been in the B-29 that photographed the bombing of Hiroshima. Why make such a claim except to bask in the glory of a “successful” mission? For their part, Nakazawa and many other bomb victims, who really were there, concealed their past, hoping to avoid the supposed shame of victimhood.28 Why not admit to having been in Hiroshima on August 6 unless there is a social price to be paid? An American on the sidelines fakes involvement in order to share supposed glory; many directly involved fake non-involvement in order to avoid supposed shame. We have all lived in nuclear denial.29 The way out is not the “creative non-fiction” of a Pellegrino but serious engagement with “what is always already there.”

I’m not holding my breath. In believing Fuoco’s story, if he did believe it, Pellegrino became the scammer scammed. But scammers often have the last laugh. James Cameron, director of Avatar, for which Pellegrino was a scriptwriter, has optioned Last Train.30 Back in the latter days of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, with Reagan prone to make factually incorrect statements, his aide Donald Regan once likened Reagan’s aides to a shovel brigade: “Some of us are like a shovel brigade that follow a parade down Main Street cleaning up.”31 That parade featured Ronald Reagan, and Regan and his fellows were doing their best to protect their leader. This parade features Pellegrino/Cameron and their ilk, with visions of blockbuster movies. We specialists are the folks with shovels. There are too few of us, and too few shovels.

Mark Selden Comment #8: Too few . . . perhaps. Yet as we write, it is Pellegrino’s work which has been discredited as a result of information and analysis from multiple sources. And important debates sparked by Japanese and international authors and artists make the subject of the bomb a realm of lively and significant debate in shaping the future of the planet. Indeed, during April and May 2010, the issues of the control of nuclear weapons will receive close scrutiny among the nations of the world in relationship to the five-year review of the Non-Proliferation Treaty taking place at the United Nations in New York and to the limited proposals for non-first strike use of the bomb floated by the Obama administration.

Appendix: Letter from Richard Garwin, dated April 5, 2010.

Dear Mark,

I haven’t read the Pellegrino book, but I have no reason to believe any of it. In looking at your excerpts, I have the following points to make. Not having viewed the book, I don’t know how far Mrs. Aoyama was from the epicenter, but because the bomb was detonated at 500 meters altitude, one can readily calculate the maximum heat involved. Before doing that, however, one might note that if she received 600 Rem (certain death of a couple of weeks), this would correspond to a mere 6 joules per kilogram of tissue, which would serve to raise the temperature by about 0.0015 degrees centigrade– not 100 degrees or 500 degrees.

If she was at a point in which she had enough radiation that she would die within an hour (say 10,000 Rem) the temperature rise would have been about 25 millidegrees.

If she was at the epicenter, then the bomb’s energy of 10**14 J of which about 1% was liberated in the form of radiation– so 10**12 J would be spread over an area of about 30 billion sq cm, so that there would be about 30 J/sq cm. This would be absorbed typically in a distance of 10 cm in tissue, corresponding to a deposition of energy of about 3 J/cc. This would be enough to raise the temperature of the tissue by about 0.8 degree centigrade.

As for the second quote, since the Hiroshima bomb was U-235 assembled by a gun-type reaction, it is true that about 560 grams fissioned of the total of about 60,000 grams. But the uranium at the time of fission was at normal uranium density which is not three times more dense than gold, but just about as dense as gold (actually, slightly less dense because the density of uranium is 19.05 g/cc, while that of gold is 19.3 g/cc.

And it is true that the sphere of gamma rays does escape the core at light speed and in a ten millionth of a second reaches a radius of about 30 meters.

As for the neutrons, there are no “heavy ions” associated with the neutrons, and the neutrons are pretty much stopped in less than a meter of material, whether it is flesh or soil or bedrock.

Neutrinos come not with the gamma rays but typically a measurable fraction of a second later from the beta decay of the fission products. Neutrinos travel at the speed of light, but there is not a significant number of neutrinos 1.24 milliseconds after detonation, even at Hiroshima. What is true is that the time required for neutrinos to traverse the 13,000 km diameter of the Earth is 40 milliseconds, and not “1.24 milliseconds”. So both the physics and the arithmetic are greatly in error in this passage.

I note on the amazon.com website that Henry Holt and Company has announced that it will no longer print, correct, or ship copies of the book due to the discovery “of dishonest sources of information for the book.” According to the publisher: ‘Mr. Pellegrino has a long history in the publishing world, and we have been very proud and honored to publish his history … but without the confidence that we can stand behind the work in its entirety we cannot continue to sell this product to our customers.'”

I can’t imagine how these errors could be due to a “dishonest source of information.”

Sincerely yours,

Richard L. Garwin

Recommended citation: Richard H. Minear with Mark Selden, “Misunderstanding Hiroshima,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 15-4-10, April 12, 2010.

Notes

1 Charles Pellegrino, The Last Train from Hiroshima: The Survivors Look Back (Henry Holt & Co., 2010).

2 Bill Schutt, back jacket. Dwight Garner, “After Atom Bombs’ Shock, the Real Horrors Began Unfolding,” New York Times, Jan. 19, 2010.

3 Joseph Kanon, Washington Post, Sunday, Feb. 7, 2010.

4 Link.

5 By dud, Pellegrino did not mean it failed to explode; he meant that it was much less powerful than expected (about this claim, see below).

6 In the note “About the Author” at the back of the book, the Ph. D. is in paleobiology; on the Henry Holt website (since scrubbed) the Ph. D. is in zoology. The pre-scrubbed website is available here. According to the publisher, “Mr. Pellegrino said that the Victoria University of Wellington [New Zealand] . . . had stripped him of his Ph.D. because of a disagreement over evolutionary theory. ‘It got to be a very hot and nasty topic in 1982,’ Mr. Pellegrino said in a telephone interview.” Motoko Rich, “Pondering Good Faith in Publishing,” March 9, 2010, p. C-1, 6. But the university has confirmed subsequently that Pellegrino was never awarded a Ph.D. Professor Pat Walsh, vice chancellor of Victoria University, called Pellegrino’s story “baseless and defamatory.” Here is her account: “He submitted a thesis which in the unanimous opinion of the examiners was not of a sufficient standard for a Ph.D. to be awarded. Following complaints from Pellegrino, an investigation was carried out by the University. In 1986, Pellegrino appealed to Her Majesty the Queen. The case was then considered by the Governor-General who disallowed the appeal. Accordingly, Pellegrino was never awarded a Ph.D. from Victoria and therefore could not have had it stripped from him or reinstated at a later date.” Quoted in Motoko Rich, “University Rejects Pellegrino Claim in Degree Dispute,” New York Times Media Decoder, March 5, 2010.

7 The full statement is available on Amazon.com’s page for the Pellegrino book. One result of the publisher’s action: as of late March, the book (list price $27.50) was selling new on Amazon.com for $90 and up, used for $60 and up. On April 7 Amazon had 13 new from $74.00, 11 used from $49.95, and 1 collectible from $499.99.

8 Hiroshima: Three Witnesses (tr. Minear, 1990); Kurihara Sadako, Black Eggs (tr. Minear, 1994).

9 David Goodman, ed. and tr., After Apocalypse: Four Japanese Plays of Hiroshima (Cornell, 1994); the playwrights are Hotta Kiyomi, Tanaka Chikao, Betsuyaku Minoru, and Satō Makoto. Hotta Yoshie, Judgment (tr. Nobuko Tsukui; Intercultural Research Institute, 1994).

10 The Crazy Iris and Other Stories of the Atomic Aftermath, ed. Kenzaburō Ōe; Grove Press, 1985; The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, eds. Kyoko and Mark Selden; M.E. Sharpe, 1989.

11 Barefoot Gen, 10 vols., Last Gasp Press, 2004-2009; Hiroshima: The Autobiography of ‘Barefoot Gen,’ tr. Richard H. Minear (Rowman & Littlefield, 2010 forthcoming).

12 Hiroshima and Nagasaki: the Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings, tr. Eisei Ishikawa and David L. Swain, Basic Books, 1981.

13 John W. Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb (Chicago, 1995).

14 The half-dozen books that are not narrowly scientific are by Akizuki, Liebow, Sekimori et al., Shiotsuki, and Pellegrino himself (his Ghosts of Vesuvius).

15 In the Five College library catalog, Pellegrino’s book comes up when the search is for the keyword “Hiroshima science.”

16 Given that the book has no footnotes, it’s impossible to say that Pellegrino actually made use of any of these medical sources.

17 Richard Garwin, Wikipedia.

18 Further, from extreme western Brazil to the coast of Ecuador is roughly 800 kilometers.

19 Cf. Minear, “Atomic Holocaust, Nazi Holocaust: Some Reflections,” Diplomatic History (Spring 1995): 347-365. Part of a symposium on the fiftieth anniversary of Hiroshima, this essay was omitted—with no mention made of the omission—when the symposium was issued as a book: ed. Michael J. Hogan, Hiroshima in History and Memory (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

20 Pellegrino refers a couple of times (30, 32) to “what became known (in the field of disaster psychology) as the Edith Russell Response: the tendency to focus on absurd details in the midst of horror or grave danger.” Edith Russell was on the Titanic and went back to her cabin before heading for the lifeboats. If you search on Google for “Edith Russell Response,” you get a grand total of two hits—both to Pellegrino! The term is apparently his invention. Whether it applies to Edith Russell I can’t say, but it surely applies to Pellegrino.

21 Pellegrino refers to Marcus McDilda, an American POW, on six pages. The locus classicus on McDilda is William Craig’s The Fall of Japan (1967). Attributing his information (p. 342) to “conversation and correspondence” with McDilda, Craig reports (p. 73) that McDilda was beaten by civilians as he was marched to the site of his interrogation, was beaten again by interrogators, then threatened with a sword by a general: “When the lieutenant did not [speak about the bomb], the general drew out his sword and held it up before the captive’s face. Then he jabbed forward, cutting through an open sore on McDilda’s lip. Blood streamed down….” In Pellegrino’s version (pp. 78-79), this becomes much different. “The first pilots questioned…died without revealing anything. … After a general cut off Marcus’s lower lip with a sword and displayed for him the severed head of an airman who had ‘pretended’ to know nothing about uranium, the pilot began designing a totally imaginary atomic bomb…” Pellegrino’s version will certainly make for a dramatic movie.

22 “Barefoot Gen, Japan, and I: The Hiroshima Legacy: An Interview with Nakazawa Keiji,” Asai Motofumi, tr. Minear, International Journal of Comic Art 10.2:311 (Fall 2008).

23 Without footnotes, without a list of interviewees and the dates of the interviews, Pellegrino’s assertions are impossible to evaluate and hence virtually worthless. At best, those survivor accounts are sixty-year-old memories of the event, and intervening events and experiences have played a major, if undocumentable, role in framing them.

24 See the sharp attacks by Dwight McDonald, “Hersey’s ‘Hiroshima’” (Politics 3.10:308 [October 1946]) and Mary McCarthy, Letter to the Editor (Politics 3.10:367 [November 1946]). See also my Hiroshima: Three Witnesses, 7-8.

25 Perloff, “In Search of the Authentic Other: The Poetry of Araki Yasusada,” in Doubled Flowering: From the Notebooks of Araki Yasusada (1997), p. 166. The “Araki Yasusada” hoax intentionally included clues to its own fraudulence. The hoaxers intended it in part as a challenge to the orthodoxies of the time in the field of literary criticism.

26 Frieling, Head of Access Services at the University of Georgia Libraries, reviewed space-related books for many years for Library Journal.

27 See, for example, Philip Nobile, Judgment at the Smithsonian (Marlowe, 1995) and Mike Wallace, Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory (Temple, 1996).

28 Hibakusha feared as well being discriminated against in their search for marriage partners; they and others feared genetic damage in future offspring.

29 Cf. Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial (Putnam’s Sons, 1995).

30 Cameron’s jacket blurb for Last Train contains unintended humor: Last Train “combines intense forensic detail—some of it new to history—with unfathomable heartbreak.”

31 Bernard Weinraub, “Criticism on Iran and Other Issues Puts Reagan’s Aides on Defensive,” New York Times, Nov. 16, 1986, p. 1.