Developmental and Cultural Nationalisms in Historical Perspective

Radhika Desai

This is the first of a two article series on developmental and cultural nationalism. The articles by Radhika Desai and Laura Hein are both substantially excerpted versions of essays that form part of a special issue of Third World Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2008, pp 397 – 428. Other essays in the collection discuss China, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, and the Middle East.

See the essay by Laura Hein, The Cultural Career of the Japanese Economy: Developmental and Cultural Nationalisms in Historical Perspective

Forging a national essence is the business of nationalists. That of nationalism’s historians and theorists is to identify the historical and social parameters within which such forging (and usually considerable amounts of forgery1) became at once possible and necessary. How did nations—new types of political communities founding a qualitatively new world order, an ‘international’ order—come to be?2 And how did they, and the international order, develop together, each shaping and being shaped by the other?

Yet there is a still deeper, structural, problem: the political (and geopolitical) processes which created nations, nationalism and the international order was inextricable from the contemporaneous development of capitalism and civil society—the one particularising, the other universalising, the one mobilising vertically, the other horizontally, the one creating nations, the other, classes. How well one set of phenomena was understood depended not only on how well the other was, but also on whether their relative importance and mutual relationship was correctly judged. This happened rarely. Instead a division of scholarly labour— between a study of nations and nationalisms largely focused on culture and a political economy of national (and international) capitalist development— emerged. This proved fatal to understanding nations. For the entanglement of capitalism and the nation-state, of class and nation, of the universalism of the law of value and the particularity of the various ways in which its inexorable operation has been dammed and channelled by national political economies remains central to understanding both.3

Connecting nationalism with the fundamental historical process of the development of capitalism also allowed the two faces of ‘Janus-faced’ nationalism—progressive and atavistic, forward-looking and backward-looking—to be put in proper historical context. And placing nation and class within a common framework also made it possible to theorise their interaction. The class character of a nationalism depended on a variety of concrete historical circumstances, in particular on the extent of the mobilisation of the lower classes.

It is, prima facie, surprising, if not astounding, that the literature on nationalism has focused so exclusively on culture, leaving out of account the vast literature on national economic development and the evolution of capitalism on a world scale,4 even though a (arguably the) central aspect of nationhood has always been one or another sort of economic development domestically and its deployment and management in international activity abroad.

In attempting to understand their real fate under neoliberalism and ‘globalisa¬tion’ in the last third of the 20th century, we depart from the widely propounded view of the decline of nations, nation-states and nationalisms. We find, rather, a transition from one historically distinct type of nationalism, combining its own cultural politics and political economy, to another: from the ‘developmental nationalisms’ which dominated in the third quarter of the 20th century to the ‘cultural nationalisms’ by the century’s close, although there are also important and thought-provoking variations. We focus on selected countries of Asia, which we know something about, but arguably our diagnosis should be more generally valid: certainly we are not proposing a category of Asian nationalisms, although I note the specificity of the nationalisms of Asia in concluding this introduction.

As the world entered the second half of the 20th century, nation-states could be divided according to whether they attempted to restrain (under social democratic regimes), eliminate (under communist ones) or harness (under developmentalist ones) the power of capital in the interest of wider groups. Japan’s ‘miracle’ years, Nehru’s, Nasser’s and Soekarno’s devel¬opmentalism, as well as Mao’s communism, stood in sharp contrast to the market-driven, capital-friendly regimes that replaced them two or more decades later and to the colonial and fascist ones which had preceded them.

Nehru, Nkrumah, Nasser, Soekarno & Tito at Bandung, 1961

Developmental regimes featured distinct developmental nationalisms. In Asia, they emerged in anti-imperialist struggles. Popular mobilisations (or minimally, as in Sri Lanka, the requirements of popular legitimacy) required these nationalisms to attempt to construct political economies of development by promoting productivity and relative equality, although accomplishment varied among the resulting capitalist developmental or communist states. While the cultural politics of these nationalisms certainly featured some more or less uncritical celebration of the ‘national culture’, developmental nationalisms typically adopted a critical stance towards important aspects of the inherited culture, as for example, the critical view of caste in Indian nationalism, or the criticism of the imperial and Confucian heritage in China. In the developmental vision, national cultures were to evolve in more scientific, rational and progressive, even internationalist, directions. In short, developmental nationalisms looked forward to brighter national futures as modern egalitarian cultures and polities and as economies of generalised prosperity in a comity of nations: they typically promised a better tomorrow.

Rather than declining in the last quarter of the 20th century, nationalisms seemed to acquire greater force, and not just in reaction to ‘globalisation’. And their nature changed. The cultural nationalisms that displaced the earlier developmental nationalisms had different names in different nations— ‘Asian values’, ‘Hindutva’, ‘Confucianism’ and ‘Nihonjinron’, for example. The cultural politics and political economy they now embodied also underwent changes and the emphasis shifted from the latter to the former. The political economy of cultural nationalisms was typically neoliberal—flagrantly unequal and not primarily concerned with increasing production or productivity so much as with the enrichment of the (expanded but still tiny) dominant middle, propertied and capitalist classes. The new nationalisms’ cultural politics—whether conceived in religious, ethnic or cultural terms— conceived culture as static, pre-given, and original although, amid the intensified commercialism and commodification of neoliberal capitalism, it was less so than ever before, and attributed to it almost magical powers of legitimation and pacification over potentially restive forsaken majorities. Thinking of cultural nationalisms as majoritarian and homogenising is easy, but also mistaken: for in the neoliberal context, cultural difference—different levels of competence in and belonging to the national culture—served to justify the economic inequalities produced by neoliberal, market-driven policies. Cultural nationalisms often took apparently multicultural and ‘tolerant’ forms as markets performed the work of privileging and marginalization more stealthily and more effectively. In contrast to the popular mobilisations on which developmental nationalisms rested, cultural nationalisms throve on the relative political disengagement and disenfranchisement which neoliberal inequalities produced. The extremist wings that cultural nationalisms had in many countries were a function of this lack of popular support. In harking back to more or less distant ‘glorious pasts’, it seemed as though what cultural nationalisms offered was not a better tomorrow, but a ‘better yesterday’.

As we see it, the transition from developmental to cultural nationalisms is implicated in the shift from developmentalism to neoliberalism. We prefer the term ‘neoliberalism’, because, despite considerable debate over its exact meaning, it is more precise, and of greater historical and geographical scope, than the more popular alternative, ‘globalisation’.5 While we mean by neoliberalism the preference for and justification of market-driven policies over state-driven ones across the whole range of policy fields practically the world over in a general sense, we do not define it doctrinally but historically. A world-wide shift in the balance of power in favour of capital underlies this shift in economic policy. It has moved politics radically to the right and recast society in market-driven ways in the last quarter of the 20th century. The categories of developmental and cultural nationalism are historical. They mark particular phases in the evolution of nations and of the international order and embody historically specific forms of political economy and cultural politics. Our attention to changes in the nature of particular non-Western nationalisms also overturns monolithic conceptions about them.

Finally, we reinsert politics into nationalisms because scholars as well as ‘politicians, political observers, and not a few ‘‘ordinary people’’, often seek to bracket of the dirty world of politics from the transcendent community of the nation.’ Nationalisms are political ideologies, but of a special sort: they define and determine the nature and limits of the modern communities that are nation-states. As such they exist in a constitutive tension with other forms of politics, as in the case of Sri Lanka. Political changes such as the shift from developmentalism to neoliberalism redefine communities, in our case through increased inequality and radical reorienta¬tions of state policy in more market-and capital-friendly directions. Redefined communities will acquire, through one means or another, new self-understandings, to wit, new types of national ideologies and cultures. Indeed, it is not surprising, in retrospect, that scholarship on nationalism burgeoned precisely at the time, in the last third of the 20th century, when attention to difference and particularity and the questioning of universal thinking became the leading intellectual trend. This scholarship, however, only accentuated the dominant tendency to understand nations culturally, in separation from political economy and it proved unable to withstand the force of the mistaken ‘globalisation’ thesis about the decline of nations and nationalisms.

Insufficiently acknowledged though it may have been through most of the 19th century, nationalism was remaking 19th century Europe as much as capitalism was, and in combination with it. The French Revolution arrayed capitalist Britain alongside Europe’s most conservative imperial powers as the French manufacturing and commercial interests struggled against the dominance of the British and the revolution threatened to inspire the British proletariat.6 In the tortuous course of the French republic and through the wars that followed, French revolutionary universalism was transformed into a distinctive form of nationalism (and not just imperialism) which echoes in eerie ways in 21st century debates over headscarves. The revolutionary formation of the French nation involved, of course, the ‘political baptism of the lower classes’ and, if revolution were not enough, the imposition of the leve´e en masse in the wars that followed ensured that the lower classes would be mobilised in the name of the nation.

French revolutionary image of liberty

Napoleonic expansion, brief though it was, also gave rise to new nationalisms in Europe, but they began as class struggles practically everywhere. Despite the nationalist character of these events, overall attention remained fixed on the imperial high noon of British expansion with which the period opened and by the ‘New Imperialism’, in which British imperialism and industrial supremacy were challenged, as the period closed. The ‘New Imperialism’ denoted intensified imperialism and inter-imperialist competition—the infamous European ‘Scramble for Africa’, the USA’s forays into Asia as its internal colonialism came to a natural end at the Pacific and Japan’s incursions into China, Korea and Taiwan—which led to the Great War and became the subject of classical theories of imperialism. However, three other critical developments also characterised this period, all of them centring on nations and nationalisms. First, the emergence of the classic ‘late developing’ nation-states—pre-eminently the USA, Germany and Japan—which successfully challenged the industrial (and consequently, the imperial) supremacy of the most successful capitalist and imperial country of their time,7 was the precondition of the ‘New Imperialism’. Second, in domestic politics a deeper intertwining of class and nation was emerging in Europe, one which was to be responsible for the defeat of the working class internationalism of the Second International on the eve of the Great War. Finally, there were the beginnings of nationalist consciousness in the colonised parts of the world, including most of Asia.

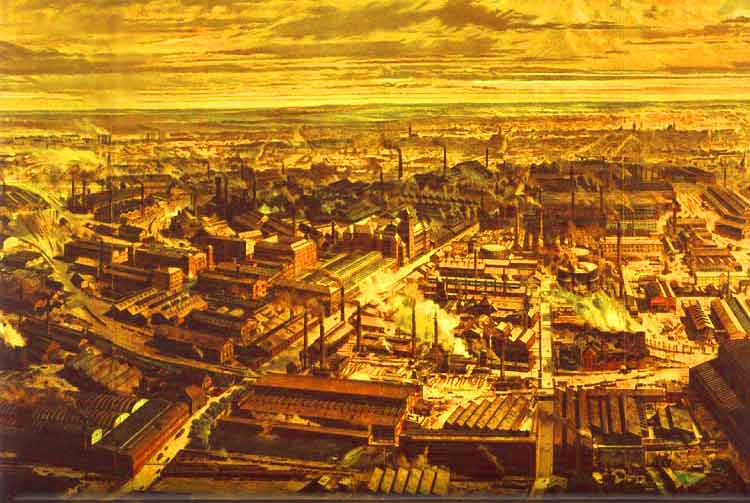

Since the start of the Industrial Revolution England had enjoyed an industrial superiority born of priority. The manufacturers of the first industrial capitalist country in the world ‘never did compete successfully against other capitalist manufacturers. What they did was to overwhelm pre-capitalist production everywhere’.8 That easy superiority, and the geopolitical order based on the imperial ‘expansion of England’, were both challenged by emerging industrial capitalist powers. In the late 19th century classic processes of ‘late-developing’ state-making and state-led industrialisa¬tion in the face of capitalist and imperialist pressures were completed in four instances, three of which were to emerge as major challengers to Britain’s manufacturing supremacy. By 1870 the unification of Germany, the Risorgimento in Italy, and the Meiji Restoration in Japan were complete and the USA had concluded its Civil War with the victory of northern industrial capitalists over the southern slave-owning plantocracy. These state elites now employed and, as necessary, invented nationality to serve their interests in a larger project of domestic modernisation and industrialisation.

The industrial revolution

Accelerated and competitive and state-led industrialisation spawned large working classes and their modern social democratic—Marxist—parties of the Second International. Its internationalism, however, was being undermined by an institutional undertow which channelled working class political energies away from revolution towards their respective nation-states in reformist engagements to an extent that only became shockingly clear on the eve of the First World War.

Significantly the nationalisms of the ex-colonial world after the Second World War, the developmental nationalisms of which we speak in this volume, had to accommodate the expectations of mobilised populations. In the colonial and semi-colonial world, including most of Asia, this period also marked the beginnings of the modern nationalist consciousness that founded the developmental nationalisms of which we speak. These too represented a historically specific combination of class and nation. Colonial incursions into Asia and Africa had originally faced and overcome resistance from pre-capitalist and pre-modern states and elites: in India this type of resistance came to an end in the wars of 1857, while in Africa or China, where colonial incursions came later, for instance, they took place towards the end of the 19th century. With the stabilisation of colonial rule, however, there emerged modern professional and bourgeois classes, creatures and often collaborators, of colonialism who would eventually come to resist it in the form of modern nationalist liberation movements. Key nationalist organisa¬tions that would play a critical role in decolonisation and national independence in the colonial world, primarily in Asia and Africa, were formed in this period: included the Indian National Congress in 1884 and Sun Yat Sen’s Revive China Society in 1894.

They typically began as elite organisations working to advance the interests of narrow professional and business elites within the rubric of colonial rule. It was not until the sharpening of popular movements, many of which, rather than being anti-colonial or nationalist, were directed at local elites and oppressions, that these organisations took a mass form. Where these popular energies and left forces were strong, these struggles overtook specifically nationalist organisations, as classically in China, to take a communist form, although that remained strongly inflected by nationalism. Elsewhere nationalisms were led by the professional and nascent capitalist classes, who were increasingly more ambivalent about colonialism and chaffing against the restrictions of racism and colonial economic policies to their own advancement. The contemporaneous nationalist and state-led catch-up industrialisation of the ‘late developers’ was a beacon to many of them and, in Asia in particular, Japan’s ascent, and particularly, its victory over ‘European’ Russia, electrified many elite nationalists. Their task now was to articulate varied, disparate and, indeed, disconnected discontents into unified nationalist movements against colonialism while containing their radicalism as far as possible. The latter required, however, concessions to those energies and radicalisms and, as we shall see in the contributions and in the conclusion, these popular and left energies were critical to the making of developmental nationalisms and imparted to them their progressive character. Germany as a defeated capitalist power lost its empire too. Between them the Great War and the Russian Revolution sundered three pre-modern empires, though with varying results. The break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire largely completed the process of nation-state formation in Europe. The Russian Revolution saw the replacement of Tsarist imperialism over the vast empire’s non-Russian populations by Leninist nationalities policy which realistically acknowledged the political force of nationalism and aimed to

‘reverse Russian privilege and undermine Great Power chauvinism’.9

The Russian revolution

Contrary to the general view that Soviet communism dogmatically suppressed nationalities, it would preserve nations where they existed and support the emergence of nascent ones by encouraging local cultures, languages and elites within the context of Soviet development, even though the Russian privilege was soon restored. It was this, rather than any eternal and primordial ‘sleeping beauty’ national sentiments, which ensured that the end of the USSR seven decades later would take the form of its break-up into constituent nations. Finally, the non-Turkish territories of the Ottoman Empire were subjected to British and French mandates, as were German territories in Africa, a half-way house to national self-determination. As long as capitalist colonialism needed the justification of racism, outright independence in these areas would prove too destabilising. Equally, however, the mandate system was a symptom of the new illegitimacy of colonialism.

With national self-determination on the world agenda after the First World War and nation-states appearing likely even in Asia and Africa, the notion of the ‘history-less peoples’ became obsolete. However, other distinctions appeared, no longer denying the possibility of nationhood to ‘history-less peoples’ but denigrating it. Particularly against the background of fascism,10 distinctions were made between liberating and oppressive forms of nationalism, political and cultural forms, and ‘civic’ and ‘ethnic’ forms, usually to the detriment of the poor parts of the world. A good example is Hans Kohn’s distinction between ‘pristine’ nationalisms—the English, American and the French—which were ‘new . . . fundamentally liberal and universal’, more liberating and less oppressive, and others which followed. The latter were condemned to focus on racial or ethnic identity with repressive and reactionary consequences.11

Such suggestions can hardly be taken seriously today. Tom Nairn showed how all nationalisms were Janus-faced,12 with forward-looking and back-ward-looking, and politically progressive and potentially atavistic, aspects. They brought much of the liberation represented by capitalist modernity, as well as its oppression. If they were responsible for violent and genocidal horrors, they also moved legitimacy from its old dynastic/colonial basis on to a new popular one, making citizens out of subjects. They brought the masses into history and envisaged material reorganisations of society which attacked the inequities of the past.

As communities, no matter how modern, nations were founded on more or less accurate narratives of origin and history, and were related to the particular communities that pre-dated them—whether they cut across or were cross-cut by these older communities. Such incongruities created ‘national minorities’ practically everywhere and they against which nations defined themselves, although, as we shall see, developmental nationalisms tended to blunt the edge of these negative dynamics. Moreover, few nationalisms were so modest as not to imagine themselves capable, as Wu says about Chinese nationalism, ‘offering universal values to mankind’.13 Eurocentric accounts dichotomising Western and non-Western forms of nationalism did, however, reinforce certain conservative and even reactionary strands and motifs in non-Western nationalisms which re-emerged in cultural nationalisms. The dichotomy was accepted but its values inverted. Kindred oppositions between state and society, modernity and antiquity, diversity and homogeneity, in which the first term referred to the West and the second to the non-West, came to romanticise and essentialise national culture and identity, as Winichakul shows in the case of nationalists (including, incidentally, Gandhi in India) who romanticised the ‘essential’ non-and anti-western traits of the national culture.

Moshe Lewin’s judgement that the USSR, rather than being communist in any meaningful sense, might more accurately be regarded as a powerful form of developmentalism suggests that 20th century communism was as much, if not more, about the logic of the uneven development of world capitalism as it was about the logic of class and capitalist exploitation.14 And after the Second World War its power was the single most important factor in the global spread of the nation-state system. It may well be the greater part of its historical significance than its flawed attempt to build communism.

The inability of the USA and its allies to defeat fascism without an alliance with communism meant that the USA was able to emerge as the pre-eminent power in the capitalist world after the Second World War only at the cost of shrinking its total size, conceding important parts of the world to communism. At the same time both the USA and the USSR had an interest in sponsoring decolonisation. The combined result was the 1945 settlement creating the United Nations and sponsoring the decolonisation which would swell its membership from 51 in 1945 to 99 in 1960, the high point of decolonisation (and 192 today), generalising the system of nation-states across the globe. Of course, although the UN’s twin founding conceptions of sovereign equality and non-intervention—the placing of the most powerful nation-states on a legal par with the least powerful and the renunciation of the sovereign right to go to war—were never fully realized, the new international order signified critical limits on imperial power.

By the 1990s it seemed to many that ‘globalisation’ was set free to consign nations and nationalisms to the proverbial ‘dustbin of history’. It was making borders and states irrelevant and nations, new and old, were undercut and cross-cut by the politicisation and commodification of cultures and identities: national as well as non-national, non-territorial ones. In this intellectual environment, focused on ‘globalisation’ and the associated ‘decline of the nation-state’, I was invited to participate in a conference on democracy and civil society in Asia with a contribution on the subject of nationalism. The invitation forced me confront the systematic discrepancies between these ubiquitous diagnoses and the transition, widely noted and puzzled over in India, from the Indian nationalism—broadly egalitarian, ‘socialistic’, modernising and productivist—of the struggle for independence and of the early decades of independence to the Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva—majoritarian, elitist, inegalitarian and subservient to metropolitan capital—which replaced it in the 1980s and 1990s.

Hindutva

I traced the transition to the contradictions— cultural as well as economic—of the first, and attempted to frame it more generally and theoretically as a transition from developmental nationalism to cultural nationalisms by pointing to similar changes in nationalism else-where—whether Japan’s Nihonjinron discourse or China’s return to ‘Confucian values’, eventually leading to this collection of essays. Indeed, new forms of neoliberal inequality may well be breeding newer minorities. There is little case for treating Asian nationalisms as essentially different from nationalisms in other parts of the world. However, one would do well to bear in mind the historical specificities of Asia’s national modernities. Excepting Japan, they feature the centrality of resistance to colonialism and imperialism. The nationalisms of Asia emerged in the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries and Asian nation-states achieved their modern state forms—usually with the attainment of independence from colonialism—around the middle of the 20th century. A third historical specificity is the wide reach of communism in Asia in the 20th century, and the centrality of Asia among the theatres of the Cold War. Asia contains some of the most important instances of states where nationalism and communism have been combined: China and Vietnam in particular. Progressive and effective though these original combinations were, they contributed to the unique horrors of Khmer Cambodia. The interaction of communism and nationalism has also shaped Asia’s destiny in the 20th century in a quite different way. Whether in Indonesia or India, Thailand or the Philippines, the containment of communism was a (capitalist) national project with all that this also meant in terms of superpower interventions, non-aligned balancing acts and internal accommodations—a variety of ‘third ways’—between capitalism and communism, between the needs of accumula¬tion and legitimation. In West Asia the presence of the communist bloc made room for a degree of national assertion among Arab states against Anglo-American oil interests as well as against Israel and in favour of more or less successful developmental and welfarist national orders.

Radhika Desai is in the Department of Political Studies, University of Manitoba.

This article was prepared for Japan Focus and posted on June 26, 2008.

Notes

I would like to thank Gregory Blue, Mark Berger, Michael Bodden and Laura Hein for their comments on earlier versions of this introduction, and Henry Heller for his on the penultimate version. Outstanding shortcomings remain my responsibility.

1 The idea that nations are ‘invented’ is at least as old as Renan’s 1882 statement that ‘Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is essential to the creation of a nation,which is why the advance of historical studies often poses a threat to nationality’. E Renan, What is a Nation?, trans Wanda Roemer Taylor, Toronto: Tapir Press, 1996. It is now generally accepted, although, as I show in ‘The Inadvertence of Benedict Anderson: a review essay on Imagined Communities on the occasion of a new edition’, Global Media and Communications, 4 (1), 2008, it is usually incorrectly associated with the work of Benedict Anderson. 2 While the cultural materiel out of which nations are fashioned is often of some antiquity—the rational kernel of the ‘primordialist’ arguments about nations’ antiquity and eternity—as I discuss below, scholars have found it hard to refute the modernity of nations as distinct forms of community.

3 It is not possible to discuss here why, correspondingly, this division of labour was less consequential for the study of capitalism. Suffice it to point to the rich comparative literature on national forms of capitalism. Of course, this is not enough and the work of theorising a geopolitics of capitalism as a specifically national and international system has only just begun. See, for example, J Rosenberg, The Empire of Civil Society, London: Verso, 1994; and B Teschke, The Myth of 1648, London: Verso, 2003.

4 The extensive contemporary literature on developmental states is usually traced to the theorisers of industrial catch-up of ‘late developers’, beginning with Carey and List, and with attempts to apply the lessons to developing countries. See F List, The National System of Political Economy, Fairfeld, NJ: AM Kelly, 1977, first published in 1841; H Carey, The Past, the Present and the Future, Philadelphia, PA: Carey and Hart, 1848; and A Gerschenkron, Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1962. A good overview of the literature on the developmental state can be found in H Chang, Kicking Away the Ladder, London: Anthem, 2004. I argue, however, that an awareness of the importance of national political economy against ‘free trade’ was more deeply rooted in classical political economy. See R Desai, ‘Imperialism’, in R Munck & G Honor Fagan (eds), Globalisation and Security—An Encyclopaedia, Vol 1, Economic and Political Aspects and Vol 2, Social and Cultural Aspects, New York: Praeger, 2008.

5 I have argued that the much-contested term ‘globalisation’ is best used to denote a phase in the management of the USA’s declining hegemony rather than any secular economic or technological processes which have, in any case, been of much longer standing than the scope of the term allows. R Desai, ‘The last empire? From nation-building compulsion to nation-wrecking futility and beyond’, Third World Quarterly, 28 (2), 2007, pp 435 – 456. R Kiely, Empire in the Age of Globalization: US Hegemony and Neo-liberal Disorder, London: Pluto, 2005 distinguishes between neoliberalism, globalisation and empire as three distinct phases of a longer neoliberal phase.

6 H Heller, The Bourgeois Revolution in France 1789 – 1815, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2006.

7 Desai, ‘Imperialism’.

8 C Leys, Politics in Britain: From Labourism to Thatcherism, London: Verso, 1989, p 42.

9 R Suny, ‘Incomplete revolution: national movements and the collapse of the Soviet Empire’, New Left Review, 189, 1991, p 112. See also his Revenge of the Past; and T Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

10 P Lawrence discusses how much Nazism skewed inter-war debates about nationalism in his Nationalism: History and Theory, London: Pearson Education, 2006, pp 59 – 106.

11 H Kohn, ‘The genesis and character of English nationalism’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 1, 1940.

12 T Nairn, ‘The modern Janus’, in the second expanded edition of The Break-up of Britain, London: Verso, 1981.

13 G Wu, in this volume, “From Post-imperial to Late Communist Nationalism: Historical Change in Chinese nationalism from May Fourth to the 1990s,” p 10.

14 M Lewin, Soviet Century, London: Verso, 2004.