A Loyal Retainer? Japan, capitalism, and the perpetuation of American hegemony

R. Taggart Murphy

Sixty five years ago, the United States emerged from the Second World War as the undisputed hegemon of world capitalism. But within a generation, neither the American will nor the American ability to continue managing the global capitalist order could be taken for granted. This essay will argue that the key to understanding the repair and continued re-enforcement of American economic and financial primacy since the system-shaking tremors of the 1970s can be found in the postwar experience of Japan and its neighbors. Within that experience lies a paradox: it was precisely Japan’s deviations from orthodox capitalist methods – the distinctive marks that characterize its political economy – that help explain the continuation of an American-centered world capitalist system long after one might have expected its manifest contradictions to bring it down.

Perry Anderson has recently written: ‘In Japan, Korea and Taiwan, the post-war states were creatures of American occupation or protection, on a front-line of the Cold War. Strategically, they remain to this day wards of Washington – planted with US bases or ringed by US warships – without real diplomatic or military autonomy. Lacking political sovereignty, yet needing domestic legitimacy, their rulers …compensated with policies of economic self-development, keeping foreign capital at bay with one hand, promoting domestic corporations with the other.’1 In other words, for reasons that go directly to the core political legitimacy of their power structures, these states have deliberately flouted neo-liberal development doctrine with its emphasis on the free movement of goods and capital. Had Japan’s power-holders in particular not felt compelled for political and historical reasons to eschew ‘liberalization’ of their economy – had they allowed capital markets, for example, to determine corporate control while arranging the incentive structure of their system to enshrine financial return as the pre-eminent goal of asset-management – their ability to support US hegemony could have been fatally compromised. Today’s global economic system would be a very different animal.

The era of American hegemony has added another contradiction of capitalism to those already identified by Marx such as tendencies towards overcapacity, overproduction, and a declining rate of profit as capitalists attempt to defend and enlarge market share. Since the emergence of the dollar in the 1940s as capitalism’s dominant currency, we have seen a secular decline in its relative value. Unlike sterling, which maintained its purchasing power through most of the 19th century and was disseminated via British capital exports, the global supply of dollars since the late 1960s has stemmed from American current account deficits, thus raising the possibility of an erosion of confidence in the dollar that ultimately could lead to a crisis of confidence in capitalism itself. This contradiction – first foreseen by the economist Robert Triffin in 1956 (he called it a ‘dilemma’) – was resolved (at least temporarily) by a Japan that had adopted an export-led growth model partly to forestall the full transforming power of capitalist relations. Among other things, relying on export proceeds and domestic savings rather than foreign direct investment to finance development helped ensure that economic and political outcomes were determined by domestic power holders rather than impersonal market forces. But the perpetuation of the export-led growth model required that Japan accumulate dollars that it would not seek to exchange either for imports or for other currencies. Since Japan in a manner of speaking would always be there to serve as the dollar’s buyer of last resort, international capitalism could avoid the contradiction inherent in a global reserve currency whose value continued steadily to decline. This crucial role Japan played in supporting the dollar, however, brought with it its own contradictions for the country in the form of a buildup of dollars that were not adequately translated into domestic purchasing power. To resolve this contradiction, the Japanese authorities deliberately created and fostered asset bubbles. The bubbles, once they imploded in the early 1990s, could not be re-inflated, but the attempts to jolt the economy back into growth with waves of credit creation supplied much of the credit that blew bubbles abroad – first in Southeast Asia, and then in the United States itself. And it has also been this Japanese credit, joined in the last two decades by China, South Korea and other Asian countries, that provided the crucial support the dollar needed to survive the bursting of those bubbles and maintain its position as the dominant world currency.

The very market-thwarting mechanisms that the Japanese put in place domestically have repeatedly been pressed into service in managing the biggest contradiction of them all: the rescue of a global capitalist order by a country that had attained wealth and power at least in part through non-capitalist means. But while the methods Japan employed may not have been fully capitalist, they depended for their success on their embedding within a global capitalist order pivoting around the financial hegemony of the United States. And when Japan’s methods began to threaten that order by devastating the traditional industrial base of capitalism’s hegemon, Japan would move to preserve the global financial order while doing its best – not always successfully – to limit capitalist liberalization at home. Here is where we find the central paradox: Japan’s very resistance to the full transforming power of capitalist relations forms a crucial explanation for both Japan’s willingness and its ability to support the global capitalist order.

The 1950s Origins of ‘The Japanese Miracle’

The thirteen crucial years between 1955 and 1968 would see Japan vault from a poor struggling country just beginning its climb out of war’s devastation to a position as the world’s second largest economy. Japan seized global leadership in a series of industries beginning with textiles and moving up the value-added chain through shipbuilding, motorcycles, a range of consumer electronics, and steel. Dominance of colour television, machine tools, and automobiles was just around the corner. These were all established industries with global markets adequately served by existing capacity in the United States and Europe when Japanese competitors suddenly arrived on the scene. It is crucial to understanding what subsequently happened both in Japan and to the global capitalist system that one keeps in mind that Japan targeted existing industries and existing capacity rather than attempting to launch new industries. In a nutshell, Japan’s strategy for economic recovery from the devastation of war required first booting foreign companies out of the domestic market in carefully chosen sectors. The domestic champions that then emerged from a protected home base exported torrential surges of goods to wrest market share abroad from Western companies and establish dominant global positions. For the strategy to work, the exports had to be of equal or higher quality than those available from Western competitors, and offered at lower prices.

In the 1950s, Japan’s power-holders stumbled onto a formula for economic growth and capital accumulation that surpassed anything the world had seen until that time. Much of their success stemmed from the way they turned to their advantage the peculiar parameters of that decade: a United States unwilling to restore real sovereignty to Occupied Japan, but also ready to buy anything Japan could sell without demanding reciprocal access to Japan’s market. At the beginning of the decade, the United States accounted for close to half the purchasing power of the planet while Japan had barely begun to recover from the devastation of war. So one-way trade with Japan hardly seemed much of a sacrifice to Washington, particularly when it formed part of a broader package that included a string of strategically placed American bases throughout the Japanese archipelago and put Japan firmly in the Western/capitalist ‘camp’ — never mind that many of Japan’s methods were hardly capitalist in that they pivoted on state control of and planning for capital rather than the unfettered workings of the market. Indeed, Japan’s power-holders had no real blueprint for what they were doing, capitalist or otherwise. Mainstream economics, whether of the Keynesian or, later, neo-classical variant, did not constitute much of their mental furniture. Trained largely in administrative law,2 their economic outlook was informed partly by the Marxian thought that pervaded the upper reaches of Japan’s academic establishment at that time.

But the men who led Japan’s march to the first rank of the world’s industrial powers were not Marxists as such, and even if they had been, the terms on which the United States formally ended the Occupation and restored to Tokyo a limited degree of sovereignty would not have allowed them to experiment either with Stalinist autarkic industrialization or the self-sufficient import substitution being implemented at the time by such avatars of dependency theory as Jawaharlal Nehru’s India or Juan Peron’s Argentina. Instead, Japan’s power-holders reconfigured institutions inherited from the war economy in order to direct scarce capital towards companies that held the promise of becoming internationally competitive exporters in order to accumulate for Japan the key global currency of the day: US dollars. These dollars could then be used to purchase the capital equipment needed for investment in the next targeted industry. Success involved careful identification of the right industry for targeting and access to the patient financing necessary to seize and hold global market share. That meant assuring predictable costs for key inputs – labour, land, money, capital equipment – which in turn required central control over their prices.

The priority given to economic reconstruction from the ruin of Japan’s bombed-out cities required no political discussion in itself, since it was taken as a given by all levels of society at the time. But the Japanese left had both the capacity and the will to make trouble if the interests of working people were not sufficiently attended to. Marginalizing the left was thus essential to the predictability required by the economic strategy Japan came to adopt. Strikes were broken, trade unions largely emasculated,3 and the possibility of a left electoral triumph precluded by a semi-rigged electoral system that favored conservative rural districts over urban. The 1955 merger (with covert financial support from the CIA) of conservative forces into a single Liberal Democratic Party virtually assured the LDP of a parliamentary majority, even if it rarely commanded more than a plurality of the popular vote.

|

Tokyo 1945 |

But the social compact that evolved out of the labour struggles of the 1950s also helped sideline the left into a ritualistic, empty sideshow. Under this compact, established companies would see to the economic security of male heads of households in return for complete management discretion over work assignments and job content. While this so-called ‘lifetime employment’ extended only to core male employees in established companies, it became a norm to be striven for by all forms of enterprise, public and private. Companies essentially could not fire a permanent employee (sei-shain) while the bureaucracy ensured that bankruptcies among major companies in established industries did not occur. Major companies were pressured to keep their suppliers on life support even in difficult times. Banks were loathe to cut off credit either to an established, first-tier company or to any of its recognized principal suppliers. And the Ministry of Finance issued what amounted to a blanket guarantee that no financial institution under its purview would ever be allowed to fail.

From one perspective, these arrangements represented a real achievement by the Japanese left since they did result in the fulfillment of a core left demand: near-universal economic security. The norms of “lifetime employment” provided a significant core of the Japanese working class with stable jobs, steadily rising incomes, access to education, and welfare benefits in a society with a relatively egalitarian distribution of income and wealth. But they also provided industry with predictable labour costs by preventing labour markets from taking root. Wages and salaries at all levels from the entry level factory worker through the CEO of a major company were established and coordinated through negotiations among a handful of key company unions and managers acting in consultation with industrial federations and the economic bureaucracy. Annual wage increases could thus be aligned with general economic growth levels. Job-hopping was unheard of among leading companies; a well-established firm would not hire someone who had worked for a direct competitor.

Just as there were no labour markets to speak of, there was no real financial market and certainly no market in corporate control; corporate decision-making rested firmly with mangement that need not answer to outside shareholders. Companies were not bought and sold in open markets under any circumstances, despite the nominal fiction of shareholder capitalism. Established Japanese companies ensured that most of their shares were held by other major companies in reciprocal shareholding arrangements. What actually traded on Japanese ‘equity’ markets was not pro-rata ownership or pro-rata shares in residual corporate profits, but simply the present value of future dividend streams that bore scant relationship to corporate profitability. Meanwhile, banks provided the overwhelming share of financing to industry while their own cost of funds and the rates they charged borrowers were centrally determined. There was nothing resembling credit analysis as a Western banker would understand the concept. Well-connected companies received credit in whatever amounts they needed; the poorly connected need not bother to apply.

It is difficult to see how these arrangements, when viewed as a totality, can properly be termed ‘capitalist’ without destroying the term’s analytical utility by reducing it to a simple label for any economy that is post-feudal but non-Leninist. Although Japan did in the years between 1955 and 1968 certainly experience ‘relentless and systematic development of the productive forces,’ to quote from Robert Brenner’s definition of capitalism,4 Japan’s ‘economic units’ did not ‘depend on the market’ for what they needed. The labour and money they required were allocated to them through centrally coordinated methods. Meanwhile, the peculiar Japanese institution of the sogo shosha or general trading companies were responsible for delivery of supplies of commodities in the quantities and at the prices required by industry.5 And, to continue with Brenner’s terms, while ‘economic units’ did respond in a fashion to ‘demand with respect to supply for goods and services,’ the demands that were given priority originated from overseas.

The Emergence of Contradictions

In 1968, Japan’s economic methods began visibly to alter both the political and economic global ecology in which they had flourished. An American presidential election was affected and possibly determined for the first time in the postwar period by trade issues with Japan.6 Meanwhile, at home, the monetary effects of Japan’s methods were beginning to pose a policy challenge.

The Korean War had provided Japan with a temporary surfeit of dollars, thanks to US military procurements which had helped jump-start the postwar economy.

|

US military procurements from Japan hit $1 billion in 1953 |

But ever since the war ended, Japan had run its monetary policy in a fashion familiar to many developing countries: using its holdings of US dollars as the principal variable in establishing its money supply. Countries lacking an internationally tradeable currency of their own – and that would certainly include Japan in the 1950s – must, one way or another, assure adequate holdings of reserve currencies such as dollars if they are to be able to pay for essential imports. All other macroeconomic variables are, by necessity, subordinated to this objective. Since the domestic money supply is the principal lever that governments can use directly to affect aggregate demand, and since the balance of aggregate demand to domestic production in turn dictates whether a country runs a deficit or surplus on trade and current account – and thus whether reserve currencies are on balance flowing into or out of the country – monetary policy must be set by relative levels of reserve currencies in countries that seek to maintain minimum levels of the latter. In the case of Japan during the 1950s and early 1960s, that meant maintaining the domestic money supply at roughly three times the amount of dollar holdings.

In the mid -1960s, however, Japan had begun to run a structural current account surplus, leading to a relentless rise in Japan’s US dollar holdings. And the yen was on the verge of becoming internationally acceptable as a settlements and reserve currency. But dollars that are simply held as reserves without any intention ever to be exchanged or redeemed for imports begin to have perverse monetary implications once they are no longer needed to provide credible backing for domestic currency.7 If such an economy is to avoid inflation – i.e., if domestic money supply is no longer allowed to grow in tandem with increasing reserves – ways must be found to offset the growing reserves. This challenge is being faced today to a greater or lesser degree by all the export-oriented East Asian economies, most particularly China, South Korea, and Taiwan, but Japan has been coping with this structural by-product of its economic methods since the late 1960s.

That was an era when, for the first time ever in its history, Japan had begun to enjoy a degree of prosperity that extended to virtually all its people. Thus understandably the reaction to the emergence of contradictions was to seek to strengthen in every way possible the postwar certainties: a stable, undervalued exchange rate and unlimited access to the American market. A new prime minister, Tanaka Kakuei, came to power in 1972 on the basis of his skill at balancing the demands of textile exporters with the need to mollify an angry Nixon administration. Nixon believed he had been double-crossed by a Tokyo that had promised a reduction in the exports in return for restoration of Okinawa to nominal Japanese sovereignty, but had then failed to deliver. After repairing relations with Washington, Tanaka went on to oversee and re-enforce the political mechanisms necessary for the economic experiments in coping with the buildup of dollars – experiments that would lead to the deliberate creation of asset bubbles. Tanaka understood that widespread prosperity would bring new pressures from relatively less well-off parts of the country; he demonstrated genius in organizing rural construction executives, farmers, and small business owners to extract public works spending and other deliberate allocations of credit from the central bureaucracy.8 Tanaka believed that building a doken kokka (“construction state”) would spread prosperity throughout the country, especially to poorer locatlities. And while this was certainly true – albeit at the price of horrendous environmental damage – the construction machine Tanaka helped create also provided for a buildup of deposits in Japan’s banking system that served to offset the growing dollar horde.

The ascendancy of Tanaka seemed to represent a fundamental power shift. Unlike his predecessors, he hailed from a regional backwater, never went to university, and presented himself as an earthy populist in contrast to Tokyo’s effete elites. But his administration helped Japan cope with its emerging contradictions without fundamentally threatening the postwar political order while leaving the power-holders in Japan’s bureaucracies, major corporations, and leading banks with continued control over economic decision-making.

But before the policy makers clustered around the Tanaka Cabinet could finish the groundwork for the deliberate creation of asset inflation, the Bretton Woods system broke up and OPEC producers seized control of global petroleum markets. Japan found itself with other and far more pressing priorities than managing the contradictions of success. Forced into accepting a rise in the exchange value of the yen at the Smithsonian negotiations of December, 1971, Tokyo’s economic mandarins were, by late 1973, coping with a currency in free fall as both foreign and domestic players assumed Japan was finished. It was not a stupid assessment. Not only was Japan absolutely dependent on imported energy whose price was now soaring, it had flourished within a global monetary, trade, and security regime that seemed by that year on the verge of collapse. The Smithsonian negotiations had been intended to resurrect the Bretton Woods system with exchange rates reset to reflect contemporary economic reality. But the agreements floundered on the absence of political will to enforce the new rates. The world found itself with a monetary system – if one can call it a ‘system’ – which initially seemed based on nothing but the whims of frightened central bankers. Meanwhile, a United States that had served for nearly three decades as the guarantor of Japan’s security and its market of first and last resort was enduring with the Watergate affair a political crisis of unprecedented magnitude while suffering its first ever defeat in war.

The pessimists about Japan’s future had not reckoned on the country’s formidable residual strengths, chief among them its institutions of control – the same institutions that had brought about the spectacular rush to growth of 1955-1968. Again, the economic bureaucracy set about rationing dollars and energy, establishing and policing domestic cartels, and maintaining dogged control of the yen in the new floating rate world. The results were, for the time, astounding. Japan pushed inflation down from over 20% (as measured by the consumer price index) in 1974 to 3% in 1975. While the rest of the world struggled through the 1970s with the novel phenomenon of ‘stagflation’ – simultaneous inflation and high unemployment –Japan’s recession was over by the end of 1975. In the teeth of the worst global slowdown since the 1930s, Japan again grew briskly, racking up not only healthy GDP numbers but also substantial increases in exports thanks in part to deliberate market interventions to keep the value of the yen lower than it otherwise would have been. Indeed, something like half the total increase in global exports in 1976 came from Japan.

Japan’s triumphant return from the economic graveyard to which it had been assigned after the break-up of Bretton Woods and the oil crisis of 1973/74 would see the country emerge as the key supporter for a reconfigured global monetary order still revolving around the US dollar. Japan would play a central and defining role in the most important American political realignment since the New Deal: the success of the so-called Reagan Revolution. And Japan would serve as a tacit model for the rest of East Asia – most importantly for China in the wake of the death of Mao Zedong.

Japan and the Restoration of Dollar Hegemony

Following the Bretton Woods collapse, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Emirates had contemplated billing their customers in a currency other than the dollar. But their ultimate decision to stick with the American currency was not driven by any evidence that Washington had either the will or the ability to halt the rapid erosion in the purchasing power of the dollar after 1973. Rather, they needed American military protection and no other currency circulated in the quantities required to replace the dollar as a global medium of exchange. The OPEC cartel could compensate for the continued decline in the dollar’s value by periodically boosting prices, but no such option was available for anyone else. And as the decade proceeded, inflation accelerated and the exchange value of the dollar continued to plummet.

Events culminated in the summer of 1978 with a full-fledged dollar crisis. The incoming Carter administration had blamed Japan for America’s escalating trade deficits, accusing Tokyo of ‘dirty floating’ — unannounced interventions to suppress the exchange value of the yen in order to maintain export competitiveness. Under pressure, the Japanese abandoned ‘dirty floating.’ The yen predictably rose to previously unimagined heights, nearing the psychologically critical ¥180/$1 barrier. The Americans had gotten what they asked for, but instead of the reduction in the bilateral trade deficit with Japan that they expected would follow a clean float, found themselves instead staring into the abyss of a dollar collapse. Japan joined Switzerland, Saudi Arabia and West Germany in a four-country rescue mission for the dollar, while Carter’s hand was eventually forced into engineering the appointment of hard money man Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve.9 Owing no political debt to Carter, Volcker set about halting the slide in the dollar’s purchasing power with steep hikes in interest rates and a concomitant deep recession that would help doom Carter’s re-election chances.

It is at this point that Japan stepped out from being a supporting actor to assuming the starring role in the resurrection and restructuring of American hegemony over global finance and the global economy – and thus the survival and recovery of global capitalism from its worst systemic crisis to that date since the 1930s. Ronald Reagan won the 1980 American presidential election with what amounted to a mandate to destroy what was left of the liberal Keynesian order that had prevailed since the New Deal and the Second World War; his campaign had succeeded in blaming this order for the inflation and other economic ills of the 1970s. ‘Government is not the solution to our problems. Government is the problem,’ is the way he famously put it. Once in office, Reagan intended to launch direct attacks on the institutions that provided for the economic security of the American working and lower middle classes. And with the breaking of the 1981 air controllers strike, his administration did succeed in dealing labour a crippling institutional blow from which it has never recovered.

But the administration lacked the political stamina to roll back directly the social welfare programs that formed the core of the New Deal legacy. A handful of ‘supply side’ gurus had seized the limelight with the notion of tax cuts purportedly so stimulative that tax revenues would rise even as rates fell. Savvier Republicans used this ‘voodoo’ economics as a cloak for their true intentions, believing that the prospect of financial disaster in the wake of the tax cuts would force the government to reduce spending. They counted on this indirect means of ‘starving the beast’ to gut the welfare state. Meanwhile, Democratic leaders such as Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill lacked the political support to withstand the administration’s tax-cut offensive, particularly after the assassination attempt against Reagan in April, 1981. They caved to White House pressure, anticipating that events would force the administration to reveal its unpopular hand when it came back to Congress to negotiate spending reductions in order to forestall financial catastrophe.10

These events never occurred: the deficit would indeed snowball, but it would be smoothly financed without a political or market crisis. With the sole exception of economist Robert Mundell (who, however, thought it would be ‘the Saudis’ who would finance the deficit11), no observer saw that this would happen. The public sector deficit soared to levels few had thought could be sustained over time without ruin. The United States emerged from the enactment of a structural Federal deficit with a robust economy that played to the country’s emerging comparative advantage in the design and packaging of complex bundles of high-value added manufactures and services. And a permanent Federal deficit would greatly enhance the power and wealth of the American ruling class at the direct expense of the working and lower middle classes.

It is critical to note here that the structural Federal deficit that forms the most enduring financial legacy of the so-called ‘Reagan Revolution’ was not a Keynesian deficit intended to plug the gap between capacity and utilization opened up by a temporary cyclical decline in private demand. For the Reagan deficits were not used to fill otherwise idle capacity; instead they financed the radical restructuring of the heavily unionized sectors of US manufacturing as well as the infrastructure of the emerging globalized economy: Wall Street, Silicon Valley, the aerospace and defense industries.

The key enabler was Japan. The Japanese economy emerged from a shallow slow-down brought on by the so-called Second Oil Crisis of 1979 with its high household savings rate intact, but with a permanent reduction in Japanese industry’s funding needs for domestic plant and equipment investment. By the simple rules of balance of payments accounting, therefore, much of the country’s savings would necessarily be deployed abroad. A US Treasury scouring the world for funds to finance the Reagan deficits would take the lion’s share. The restructuring of the American economy – and the concomitant realignment of American class power – would be financed with barely a hitch.

While the Japanese may have stumbled without deliberate political choice into their role as America’s enabler, the contradictions – political, financial, and social – would become increasingly burdensome. Japan’s response to events in the decade that followed the collapse of Bretton Woods had been almost entirely reactive.12 There was never any real debate over what the country should do. Even the financing of the Reagan Revolution had not been a thought-through, conscious political decision, but simply a reaction to existing financial circumstances. True, 1980 saw the revision of the Foreign Exchange Control Law, speeding the ability of Japanese financial institutions to deploy assets abroad by eliminating the need to obtain clearance from the Ministry of Finance for each transaction, but this was simply an acknowledgement of reality – the recycling of the Japan’s growing surpluses needed to be an efficient process.

There was one problem. A steep rise in the value of the yen against the dollar would wipe out all yen-equivalent profits from Japanese investments in US Treasury securities. Japanese insurance companies, after all, must settle claims in yen, not dollars; if they paid 240 yen per dollar for a Treasury bond on issue but got back 200 yen or less when the bond matured, the interest income would be wiped out by the exchange loss. But asset managers in the early 1980s calculated they would have to get back fewer than 180 yen on the dollar for these investments to become money-losing propositions for them. That 180 number was the rate that had served as the firewall during the depths of the 1978 dollar crisis. Japan’s asset managers interpreted the events as proof that the US and Japanese governments together had the capacity to ensure the crisis would not be repeated.

Indeed, as the 1980s wore on, fears of another dollar crisis seemed remote as global demand for dollar securities drove the American currency to post Bretton Woods highs. Enjoying the advantage of a cheap yen, Japanese manufacturers embarked on a kind of second golden age as industry after industry fell to the Japanese onslaught: automobiles, earth moving equipment, colour film, machine tools, and a whole range of consumer electronics from the recently introduced VCRs through portable listening devices. Japan would even set its sights on the hot new industry of semiconductors.14 But while Japan’s manufacturers may have been basking in unprecedentedly favorable conditions, the country’s politicians found themselves pulled into the early stages of the desperate late 20th century struggle within the American ruling class between the avatars of the ‘new economy’ of Wall Street and Silicon Valley and the champions of older industries. The Reagan Revolution would succeed in destroying the political power of the American white working class by its assault on unions and by the economic devastation its deficits would indirectly wreak on that class’s traditional employers in the so-called ‘rust belt’ manufacturing industries. (Working people of colour had little political power to destroy.) But substantial factions of American capital derived their wealth and power from these industries and they reacted with fury to what they saw as ‘unfair’ Japanese assault on their industries – fury that manifested itself in pressure on Washington and waves of hostile sentiment aimed at Japan.

The ideological constraints within which received opinion operated – the fetishization of ‘free trade’ and ‘free markets,’ the deliberate blindness to the power and class struggles that inevitably accompany economic transformation – meant that the only politically acceptable way conceptually to frame the crisis was to ascribe it to currency manipulation. Japan must be ‘manipulating’ its currency in order to grant its exporters an ‘unfair’ advantage. (If the charges leveled today at China sound like an echo of this line, that is not a coincidence.) Even standard neo-classical economics would teach that a strong dollar was an inevitable outcome of the success of Volcker and Reagan in halting the erosion of the dollar’s purchasing power, re-affirming the dollar’s role at the center of global finance, and then exploiting that role to run up large, politically painless deficits. But a direct challenge to free market orthodoxy was inconceivable in American ruling circles; instead business leaders such as Caterpillar’s Vice President Donald Fites hunted about for evidence that the Japanese were engaged in various supposedly sneaky practices to keep the yen undervalued. They hoped to give the US government an ideologically acceptable excuse to intervene in foreign exchange markets.14 And they believed their own notices: that the loss of so much of the American manufacturing base to Japanese competition was due to currency manipulation and could be fixed if dollar/yen rates were realigned. ‘There isn’t anything wrong with the US-Japan trade balance that ¥180/$1 rate wouldn’t solve,’ was a widely repeated remark in the Washington of the time.15

Japan’s power holders may have felt like canoeists caught in the unforeseen torrents of a raging river; all they had consciously done, after all, was buy the Treasury securities on offer and export well-made products at low prices. But they did start paddling furiously once they understood the extent of the potentially destructive power of the American political currents and eddies. Competing factions of Japan’s political elite put aside their differences to engineer the removal of a woefully inadequate Suzuki Zenko as prime minister and replace him with Tanaka disciple Nakasone Yasujiro. Nakasone worked with key bureaucrats in the Ministry of Finance to signal Washington that Tokyo would not be amiss to a coordinated effort to bring the dollar down a bit. And he helped prepare the country for the adjustments necessary when the yen would begin to rise again, assuring Japanese industry that one way or another, their loss of an exchange advantage would be made up to them.

The realization that Japan would have to do something to avoid being dashed on the rocks of American hysteria was accompanied by an awakening on the part of Japan’s elite to the potential for accidents inherent in the country’s growing financial power. On May 10, 1984, a mistranslated report that surfaced in the Japanese business press about the supposed problems of the Continental Bank of Illinois led Japanese fund managers to pull their deposits from the bank without notifying the Japanese authorities or, in some cases, their own senior executives. The Japanese had become so important to Continental’s funding that the bank had to go to the Federal Reserve for an emergency bailout the next day. The Japanese had sparked a full-scale bank run without the slightest intention of doing so.16 The Continental Illinois bailout may have been a relatively minor incident, but it underscored two new realities: that whatever Japan did would move markets. And that events could very quickly get out of control.

This became more and more evident in the aftermath of the Plaza Accord of September, 1985 – the piece of theatre jointly staged by Washington and Tokyo at New York’s Plaza Hotel with a supporting cast from London, Paris, and Bonn to demonstrate their collective disapproval at the dollar’s strength. The players intended to induce traders in the foreign exchange markets to bid the dollar down. Narrowly speaking, the Accord was a great success: the dollar did fall, farther than anyone expected it to, or even wanted it to. The ¥180/$1 rate that had been seen for close to a decade as the ceiling beyond which the yen could not possibly rise was breached for good, never to return. But Japan’s trade surplus continued to climb, the US current account deficit to worsen, and the restructuring of the American economy to pick up steam. In 1986 as the dollar was steadily sinking, Microsoft would go public, the historic Homestead Steel Works in Pittsburgh would close its doors, and “junk bond” house Drexel Burnham Lambert would report net profits of over $500 million, the most money that a Wall Street firm had ever earned to that point.

|

The 1985 Plaza Accord strengthened the value of the yen against the dollar |

For despite the impressive campaign mounted by the world’s leading central banks in the wake of the Plaza Accord to lower the exchange rate of the dollar, no one in Tokyo or Washington actually wanted to see the dollar dethroned as the universal settlements and reserve currency. And until that happened, the United States would continue to run trade deficits that were automatically financed by its trading partners. But in the sudden and seemingly unstoppable rise in the yen, the Japanese had to contend not only with an extra burden on their exporters but what in retrospect was quite obviously the end of the benefits flowing directly to Japanese households from the export-led growth model. To compensate Japanese industry for their strong currency burdens and to keep the good times rolling at home, the Japanese authorities took out of the closet the tools that had first been forged during the break-up of Bretton Woods in order to blow bubbles in asset markets.

Pioneering ‘Bubblenomics’

It is perhaps appropriate that the Japanese were the pioneers of ‘bubblenomics,’ to use Brenner’s term, since the Japanese economic strategy had involved the deliberate creation of excess capacity in global industries. The late 1980s Japanese bubble represented an attempt to resolve the contradictions of that strategy that had finally caught up with Japan. Brenner has argued that at this critical juncture the Japanese economic authorities ‘pioneered’ a ‘remedy’ for the ‘long term weakening of capital accumulation and of aggregate demand (that) has been rooted in a profound system-wide decline and failure to recover of the rate of return on capital, resulting largely – though not only – from a persistent tendency to over-capacity, i.e., oversupply, in global manufacturing industries.’ That remedy involved ‘titanic bouts of borrowing and deficit spending, made possible by historic increases in … paper wealth…enabled by record run-ups in asset prices.’17 Brenner was writing specifically of what happened in the United States in the mid 1990s when ‘corporations and households, rather than government’ would ‘propel the economy forward’ through heavy borrowing, but he was right to draw attention to the way in which the Japanese had pioneered things.

The contradictions stemmed directly from Japan’s economic methods: methods that made it harder and harder for the United States to exchange goods of real value for Japanese exports. With the loss of so much of the traditional American manufacturing base to Japanese competition, and the reluctance on the part of Japanese companies to import anything that could be manufactured at home, the bilateral trade deficit continued steadily to widen. ‘You Americans just don’t make anything that we Japanese want to buy anymore’ was a commonly heard refrain in late 1980s Japan. But if that was truly the case, then the only way to keep Japanese sales going was to transfer purchasing power to the customer – i.e., the United States – which is what happened. And the ultimate source of that purchasing power was Japan’s domestic households. To rephrase things, by accepting American IOUs instead of goods of real value as payment for its exports, Japan’s aggregate demand was being deliberately sent to the United States in order to keep Japanese factories running.

The contradiction here goes to the heart of Brenner’s contention that the ‘persistent tendency to over-capacity in global manufacturing industries’ is at the root of the growing severity and frequency of financial crises that have beset the world since the collapse of Bretton Woods. Individual Japanese companies did not treat profit-making as a raison d’être. The economic system in which they were embedded and the incentive structure of that system rewarded technological progress, gross revenues, cost-reductions on the assembly line, and market share. Profits were incidental and could be shameful if excessive; certainly no Japanese CEO would hold out profits as an overriding corporate goal. Even the recovery of fixed investment costs was largely a peripheral concern; as long as established Japanese manufacturing companies generated enough revenue to cover their variable costs, they were essentially protected from the risk of bankruptcy and they received the financing necessary to make whatever plant and equipment investments were required to capture and hold market share. Japanese management did not face pressure from equity markets for return. Financing was almost entirely in the form of short-term bank loans (themselves financed by household deposits) that were regularly rolled over as a matter of course; thus the fixed costs incurred from capital investment were essentially socialized since Japanese companies faced no existential risk from capital investments that did not pay for themselves.

Japanese companies could thus survive and even thrive at rates of return on invested capital (‘ROI’) and rates of return on equity (‘ROE’) that would spell takeover or bankruptcy for at least their American counterparts, if not their European ones. But that did not spare the Japanese system as a whole from the consequences of anemic returns on its aggregate invested capital. Japan’s postwar economic structure had been, as we have seen, configured not to generate high rates of return but to generate high rates of dollar holdings. Since these dollars over time were increasingly used simply as a form of consumer finance for Japan’s export customers rather than converted into domestic purchasing power, the economic contradictions became unavoidable. For a brief period of time – the years between the onset of the Reagan Revolution and the Plaza Accord, i.e., 1981-1985 – the dollars pouring into the coffers of Japan’s export champions enabled them to report unaccustomed levels of profitability, even if those dollars did not fully translate into domestic purchasing power. But once the dollar flows lessened with the post-Plaza run-up in the value of the yen, Japan’s policy makers were confronted with the reality that the strategy of export-led growth was no longer sufficient to propel the economy forward.

They understood this. A senior Bank of Japan (‘BOJ’) official was quoted anonymously as saying in explaining the bubble: ‘We intended first to boost both the stock and property markets. Supported by this safety net – rising markets – export-oriented industries were supposed to reshape themselves so they could adapt to a domestic-led economy.’18 The MOF and BOJ had the tools to steer credit directly into real estate and stock markets.19 Since Japanese banks lend primarily with the collateral of real estate, soaring real estate prices were both a result of the waves of liquidity pouring into the economy and the means by which that liquidity was transformed into cheap financing.

The deliberate asset inflation of the late 1980s succeeded in postponing a reckoning with the contradiction that lies at the heart of the export-led growth model: that if it succeeds, a country must at some point either reconfigure its economy or, if it wants to keep the model going, transfer purchasing power to its customers. The mechanisms that sparked the Japanese bubble did compensate for a while for the systematic transfer of domestic purchasing power abroad by showering money on households, albeit unevenly. The bubble deceived corporate treasurers into thinking that capital financing was essentially free; companies went on a debt and capital investment binge that bought for Japan the most advanced manufacturing base ever built as well as a lot of fancy headquarters buildings and lavish golf courses.

The bubble provided critical support for the dollar in the wake of the 1987 stock market crash. Like the collapse of Continental Illinois, the crash started in Tokyo. This time, rather than the mistranslated press report that had led Japanese fund managers to start pulling their money out of Continental Illionois, it was the announcement of the August, 1987 trade numbers that panicked them into dumping their holdings of US Treasury securities. A near-halving of the dollar’s value since the Plaza Accord had not produced any reduction in the US-Japan bilateral trade imbalance. With the dollar buying fewer than 140 yen, Japanese investments in US Treasuries made earlier in the decade were already well under water. Fund managers expected renewed pressure on the currency and like good traders anywhere, tried to close out their losing positions before they dropped any further. As bond prices fell, yields went up and investors abroad began transferring money out of stock markets into bond markets. The Dow Jones plummeted by nearly 23% in a single day. Fortunately for the dollar and the American markets, however, the MOF was able to halt the global stock market collapse by orchestrating a recovery in Tokyo.20 It followed that by arm-twisting Japanese fund managers to renew their investments in dollar securities; the BOJ re-enforced the arm-twisting by yet more credit creation at rock-bottom interest rates. Credit flowed back into dollar instruments without putting any damper on the Japanese boom which, by the late 1980s, had begun to look like one of the great manias in global financial history.

Asset prices continued to skyrocket, reaching absurd levels. By 1989, the extrapolated land value of Tokyo and its suburbs exceeded that of the entire United States plus the market capitalization of every company listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Meanwhile, the Tokyo Stock Exchange accounted for close to 50% of the market capitalization of the entire world. Even more worrisome to Japan’s power-holders than these clearly fantastic prices were the social effects of the bubble. A down payment on a small house within commuting distance of central Tokyo or Osaka now lay far beyond the reach of ordinary middle class families whose husbands and fathers had formed the foot soldiers of the economic army that had conquered global markets. But people who had title to plots of dirt anywhere in Japan’s urban areas found themselves rich beyond their wildest dreams. Social control mechanisms began to break down as youngsters started to disdain the traditional decades of uncomplaining hard work that had formerly been the quid-pro-quo for economic security. An entrepreneur rumored to be descended from Japan’s pre-modern outcast class deliberately set out to create a labour market and engaged in wholesale, bubble-fueled bribery to purchase political protection for his business. This ensuing ‘Recruit’ scandal as it was called after the name of his company, reached to the highest levels of the Japanese power structure, bringing down the government of Prime Minister Takeshita Noboru, another important Tanaka disciple.

The authorities were frightened. The bubble had largely accomplished its purposes. Foreign exchange markets had stabilized, while Japanese industry had used the waves of financing thrown off by the bubble to equip itself with the most formidable manufacturing base ever built. So beginning on Christmas day, 1989 with a steep hike in interest rates, the authorities deliberately set out to take the steam out of the bubble. But they lost control of events. The authorities had had the tools to ratchet up real estate prices. Once prices began to fall, however, they could not stop them. Waves of investment had saddled Japanese companies with debts that they discovered were not ‘free’ after all. It would take them years to plug the gaping holes this debt opened in their balance sheets.21 And the MOF could not, after all, honor its implicit guarantee to all financial institutions under its purview.

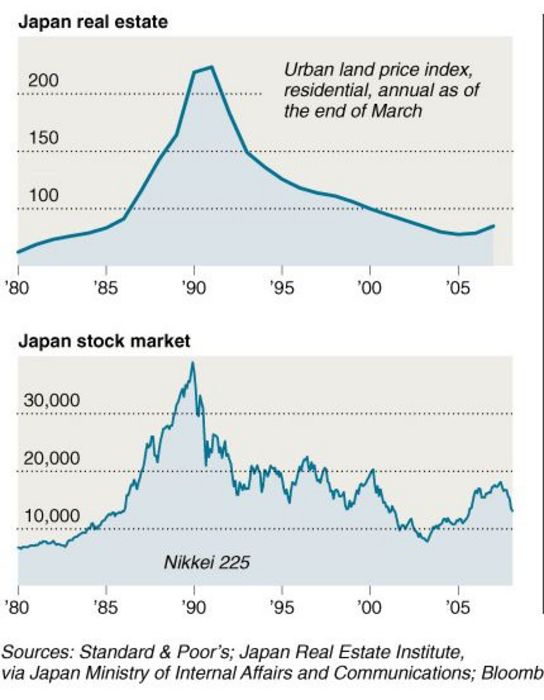

|

The bursting of the bubble reflected in Japanese land andstock market values |

Nowhere to Turn?

Despite the increasing stagnation that gripped the Japanese economy in the wake of the bubble’s collapse, Japan continued to provide critical support for the dollar and for American hegemony straight through the 1990s. This was most evident at the time of the Mexican peso crisis of early 1995 when it appeared for a while that the US had lost the will and the ability to bail out a country in its own backyard. The passage of NAFTA had led to an unsustainable surge in hot money flowing into Mexico chasing supposed high returns; when these returns proved ephemeral, the money flowed right back out, bringing on a balance of payments crisis.

Bailing Mexico out, however, would require additional funding for the IMF. An unlikely coalition of left Democrats hostile to the IMF and Republicans seeing an opportunity to embarrass the Clinton administration succeeded in blocking passage of legislation to top up the IMF’s coffers. Clinton’s new treasury secretary, ex-Goldman Sachs co-chair Robert Rubin, found a loophole around the Congressional obstruction. In the process he halted a global run on the dollar as serious as any since 1978. But even when other currencies stabilized against the dollar, the yen continued to soar. By May, it took only 79 yen to buy a dollar, a rate far below what most Japanese exporters needed to cover even their marginal costs – i.e., they were losing money on each sale they made abroad.

The resulting panic in Japan saw the MOF go outside the usual order of bureaucratic succession to appoint Sakakibara Eisuke as Director General of the International Finance Bureau, the key official dealing with currency issues. Sakakibara had a well-deserved reputation as a maverick and gadfly, but he got the nod on the basis of his purported relationship with Lawrence Summers, then Undersecretary for International Affairs in the US Treasury (Sakakibara had been a visiting professor in the Harvard economics department when Summers taught there). Sakakibara flew to Washington in June and negotiated with Summers and Rubin what amounted to a quid-pro-quo: American help in bringing down the yen/dollar rate in return for a tacit agreement that Japan would support the market for US Treasury securities.22 With the Clinton administration at its political nadir in the wake of the 1994 midterm election losses and worried about its re-election prospects, the last thing it needed was a bond market crisis that would send interest rates skyrocketing.

The intervention, staged in August, 1995, accomplished its goal of taking the yen/dollar rate back over 100. Rubin masterminded the tactics used to shift sentiment in the foreign exchange markets, but the fire power came from Japan in further waves of liquidity creation. The Clinton administration would also go on to help provide political cover for the bail-out package needed to avert a full-fledged banking crisis in Japan. Bailing out the banks was as politically unpopular in the Japan of 1998 as it would prove in the US of 2008, but after the failure of several financial institutions within weeks of each other in late 1997, there was no choice if a meltdown was to be avoided. Rubin convinced the President to make a well-publicized telephone call to then-Japanese Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro urging him to do what was necessary. The Diet passed a ¥72 trillion bank bailout package, the single largest expenditure ever legislated to that point by a government in peacetime.

As the 1990s drew to a close, it seemed that the United States and Japan had evolved a sort of modus-operandi in which Washington and Tokyo would use each other to provide political cover for arrangements needed to keep the global financial order going. There had been a brief period in the late 1980s when the Japanese elite allowed themselves to be seduced by dreams of succeeding the US as the hegemon of the global economy. The events of the 1990s soon disabused them of this notion, however. It was not simply the loss of control after the imploding of the bubble and the inability to restart the engines of growth in its wake. But also the realization that dominance of key upstream components and manufacturing technologies did not, after all, confer the economic leadership that Japan’s decision makers had thought was within their grasp. American companies that had barely been heard of twenty years earlier – Microsoft, Intel, Apple, Cisco – emerged as the key pace setters in the ‘new’ economy growing out of the technological revolutions in computers and telecommunications. For it was no longer so easy to divide ‘manufacturing’ from ‘services’ — much of the profits in the new industries came from the bundling and packaging of both.23

In this new world, trade conflicts between the US and Japan essentially disappeared. The last serious one had occurred in 1994 over auto parts; Rubin, worried over the effects on the bond market of a visible trade impasse, had persuaded the White House to fold its (quite strong) hand in its efforts to dismantle barriers to sales of American auto parts in Japan. The two countries were settling into a rough division of economic labor that saw Japan continue to dominate the high-value added end of manufacturing while the US pioneered new industries and packaged new products. Boeing would announce plans for what would become the revolutionary 787 Dreamliner with Japanese companies responsible for the manufacture of the technically sophisticated wing and wingbox. Apple would design and bring on-stream gorgeous new gadgets with the LCD screens and many other high-value added components manufactured by Japanese suppliers.

Bubbles Bubbles Bubbles

But this was not the end of the story. The waves of credit creation undertaken by the BOJ to help bring down the yen in the wake of the Mexican crisis and to stabilize a tottering banking sector directly set the stage for the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. The Japanese banking system may have been rescued from a complete meltdown, but individual banks, sensitized now to the possibility of failure, were still loathe to lend domestically. The BOJ’s credit creation did not spark a domestic investment boom; instead the rivers of cash found their way into the so-called carry trade: yen borrowing by hedge funds and other foreign players with the proceeds swapped into a higher interest currency such as US dollars. From there, much of the money went into emerging markets abroad, in particular into the booming economies of southeast Asia where the tidal waves of credit fueled unsustainable bubbles in places such as Bangkok.

The bubbles burst. Before the Asian financial crisis would play itself out, Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, and Russia would see governments fall in the wake of balance of payments impasses. Events would culminate in the collapse of the American hedge fund Long Term Capital Management that threatened to take much of Wall Street with it. But the lessons learned by governments in East and Southeast Asia – both in those countries that had been directly affected and in those countries that had escaped the worst – was never to put themselves in positions again where balance of payments difficulties could bring on political crisis. That meant redoubling efforts to accumulate international reserves – i.e., dollars – with export competitive industries. It was the old Japanese strategy of the 1950s updated to the realities of the new millennium.

This was most obvious – and most significant – in China. China would simultaneously and in defiance of all conventional wisdom rack up both current account surpluses and capital surpluses as foreign investment poured into the country (see graph found here). The inevitable result: a growing horde of international reserves, mostly consisting of direct and indirect claims on the US government. The wall of credit sloshing back into the United States from China and its neighbors permitted the incoming George W. Bush administration to run a repeat of the Reagan Revolution. Thanks to Asian appetite for US Treasury securities, the Bush borrowing spree was as politically painless as that of twenty years earlier. Again, cost-free military adventures could be launched with impunity while torrents of cash were channelled by Wall Street into the pockets of the American rich.

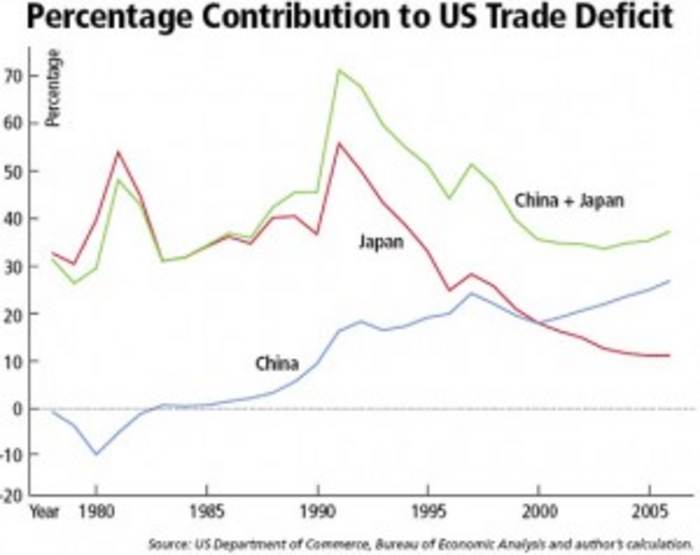

|

Chinese and Japanese components of the US trade deficit |

Meanwhile, the onset of the new millennium paradoxically granted Japan a temporary reprieve in its attempts to escape the ‘policy trap’ of its inability to move away from the export-led growth model. Although Japan continued to pile up dollars, the boom in China not only gave Japan a new partner in supporting American hegemony but provided a real path out of the debt hole left behind by the imploding bubble economy of ten years earlier, thanks to Chinese orders for Japanese capital equipment. Cheap Chinese goods smashed many of the trade barriers that had long kept foreign goods out of Japanese stores, meaning that while real incomes remained stagnant for Japanese households, the cost of living fell even faster. And Japan’s governing class found in Koizumi Junichiro an answer to Ronald Reagan and the UK’s Tony Blair: a slick, media-savvy professional whose talk of reform and sunny, can-do demeanor would divert for awhile worries over structural economic pathologies and widening social fissures. Koizumi would serve as prime minister from 2001 to 2006 – the longest period in office since Nakasone. He would be even more obsequious to Washington than Blair. Part of that sycophancy involved a public commitment to reshape the Japanese economy along neo-liberal lines.

But while a great deal of neo-liberal talk emanated from Koizumi and the people around him, that portion not whipped up directly for Washington’s consumption turned out to be largely a cover for loosening the social compact forged in the 1950s. Companies were essentially given the green light to rely on so-called fureeta – temporary workers who did not receive the implied guarantees of economic security that had customarily come with employment at a Japanese company. Koizumi’s most famous ‘reform’ — the overhaul of the Japanese post office including the postal savings system – originated within the MOF as an effort to reduce the drain on the Japanese treasury of white elephant spending in rural districts that were losing population. Those who took Koizumi at his word – both Japanese entrepreneurs attempting to introduce genuine markets for corporate control and foreign investors launching takeover bids for what they saw as poorly managed Japanese companies – were almost invariably stymied.24 Japanese power holders continued to display ambivalence about the transforming power of capitalist relations; they remained unwilling to turn over decisions about the direction of the economy to markets they could not control and did not trust.

The Lehman Shock and the End of Japan’s Export-Led Model?

Koizumi’s retirement in 2006 was followed a few months later by the onset of the subprime crisis in the United States that would lead to the worst financial meltdown since 1931. While Koizumi was still in office, it had been possible politically for Japan to tolerate a continued muddling through. The country would adjust to a no-growth economy, no longer particularly vital, but with a panoply of cutting edge manufacturing technologies sufficient to ensure it could still pay its way in the world. Japan seemed resigned to becoming a sluggish Asian Switzerland. It would continue its role, joined now by China, in supporting US financial hegemony, thereby assuring the continuation of a global environment that allowed it to survive, if not notably happily.

But the ‘Lehman shock’ of September, 2008 made this ‘muddle through’ untenable. With Chinese exports temporarily derailed by the US implosion, Japan’s economy went into a tailspin – partly because Chinese orders for Japanese capital equipment plummeted, and partly because Japan’s much-vaunted manufacturing supremacy was being challenged like never before. Not a single Japanese semi-conductor chip could be found in Apple’s hot new iPhone, for example, while the display panels were being made in Korea. The dollars being sent back into the US banking system – whether directly or indirectly via China – were no longer translating into demand for Japanese goods.

In retrospect, doomsayers over the end of the Asian model may have been a trifle premature – China has, in a striking mirror-image of Japan’s performance in the mid 1970s, managed to put its economy back on track, stunning much of the world in the process and providing some glimmers of hope to Japan as well; Japanese sales of capital equipment to China began to recover, halting the rapid deterioration in Japan’s trade accounts. But none of this was evident in time to save the LDP from electoral defeat. Koizumi was succeeded by two colourless LDP hacks, neither of whom managed to stay in office for more than a year, and finally by an Aso Taro who projected, like Koizumi, a somewhat kooky persona, but without any of Koizumi’s savvy or ability to reach the average voter. With Japan’s governing apparatus seemingly helpless in the face of the economic meltdown, the LDP was decisively voted out of power in August, 2009.

The election held out the hope that Japan finally had the leadership needed to change the country’s direction. The people who led the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) to victory were quite explicit that they were not simply running against the LDP but against the entire governing setup that left significant policy decisions with the bureaucracy – that in the words of long-time Japan observer Karel van Wolferen, they intended to establish a genuine government.25 Alas, they reckoned without the entrenched power of the interests they sought to displace. Even before the DPJ’s victory, its opponents had succeeded in delivering a blow that foreshadowed a crippling of the party’s ability to carry out its program. They had forced the resignation of its leader, Ozawa Ichiro, yet another Tanaka disciple and arguably the most brilliant of the lot. With his clear grasp of the underlying historical and institutional factors that block Japan’s progress — very much including its entanglement with the United States — and his call to overhaul the country’s governing arrangements, Ozawa had been at the vortex of Japanese politics since 1992 when he led a walkout of scores of legislators from the LDP. But on the eve of the DPJ’s electoral triumph that was largely his doing, he fell afoul of the usual establishment method of dealing with ambitious politicians who threaten real change: rumblings from the public prosecutor of an investigation that are then amplified by the establishment press. Ozawa was forced to give way to the diffident Hatoyama Yukio as prime minister.

As I have argued elsewhere,26 Hatoyama’s downfall – he had to resign a scant 8 months after he took office – was a direct consequence of Washington’s unhappiness with signs the DPJ was contemplating security and foreign policies that might deviate from American priorities. We have seen in this essay that Japan played a pivotal role in supporting the hegemony of the US dollar over global finance and thus by extension of American management of global capitalism. But Tokyo has also given lip service to every American foreign policy goal since the Korean War. And the country has provided the American military with its key logistical anchor in East Asia, notably through its vast military establishment on Okinawa.

Okinawa only came under Japanese control in the 17th century and was not incorporated into Japan proper until 1879; during the waning months of the Second World War, Okinawa suffered horribly; many Okinawans to this day believe the Imperial Government treated them as dispensible cannon fodder. The American Occupation that ended for the Japanese mainland in 1952 lasted for another twenty years in Okinawa; even today, some four decades after the formal return of the island to Japanese rule, it continues to be honeycombed with US military installations. The DPJ’s electoral platform had called for a re-assessement of the American presence in Okinawa, holding out the possibility of complete removal of US bases.

The Obama White House and the Pentagon reacted with fury to such a display of independence from a Tokyo that Washington had long been accustomed to regard as the capital of a servile protectorate. The Americans treated Hatoyama with calculated contempt, partly at the instigation of the network of Japanese establishment voices on which Washington has long relied for its intelligence on Japan. By assuring Washington that it need not deal with the Hatoyama administration as a substantive government, these spokesmen for LDP interests succeeded in their underlying purpose: painting a picture for the Japanese public of an ineffective and amateurish prime minister who threatened Japan’s supposedly most important security relationship. When Hatoyama was unable to comply with a deadline purportedly set by bureaucrats in the Foreign and Defense ministries to reconcile Pentagon demands with the wishes of Okinawa’s own residents – an impossible task for any prime minister — he resigned.

His successor, Kan Naoto, has political roots in the Japanese left and while he is obviously a decent man who commands considerable public affection, he appears to lack the independence of mind needed to stand up either to Washington or to entrenched domestic interests, much less to conceive and steer a new course for his country. While serving as Finance Minister in the Hatoyama cabinet, he had clearly fallen under the influence of senior MOF bureaucrats obsessed with Japan’s fiscal deficits. The moment he became prime minister, he began to hint about raising taxes, talk that probably deprived the DPJ of its control of the Upper House in the election of August 15, 2010. With Washington crowing about the success of its “tough love” for Japan that pushed Hatoyama out of office and the DPJ having forfeited its clearest shot at undisputed control of the Japanese Diet, Ozawa made one last desperate gamble to save the edifice he had built, challenging Kan for party leadership.

He failed, losing the September 14 party election. While he should never be underestimated, his indifferent health, his indictment on corruption charges in early October, and high negatives with the wider public probably end any chance he has ever to be prime minister. And while it is too early to say definitively that the window of opportunity to reorder Japan’s political and economic priorities has closed on the DPJ, literally within hours of Kan’s victory, there were already distressing signs of a return to business as usual. Under Hatoyama, the DPJ had hinted it was prepared to cope with the consequences of a strong yen, even using it as a lever in restructuring the economy. But on September 15, with Kan’s undoubted approval, the Bank of Japan dredged up its tired old recipe for propping up Japan’s traditional export champions: intervening in the foreign exchange market to weaken the yen. Meanwhile, a Japanese Coast Guard confrontation with a Chinese fishing boat in disputed waters was being allowed to escalate into a major diplomatic imbroglio. It all suggested that policy was back firmly in the hands of those who thought and acted like bureaucrats — a political formula both for continued economic decline and for an ever more costly inability to cope with the rapidly changing power dynamics in East Asia, where a new superpower rises just over Japan’s horizon.

Passing the Baton?

China and other Asian countries for their own reasons adopted key parts of the Japanese model, but have found themselves facing many of the same contradictions – in particular, a need to prop up the dollar’s hegemony lest they destroy the value of their own holdings and wreck the machinery by which their customers finance purchase of their exports. Indeed, the very emergence of China as such an important overseas prop for the US dollar encourages Washington to treat Tokyo as little more than a staging ground for the US military now that Japan increasingly plays second fiddle to China in dollar markets.

But China is a very different country with a very different history. Oddly enough for an ostensibly Marxist-Leninist polity, it often seems less ambivalent in its embrace of capitalist relations. This may be due to the legitimacy enjoyed by the Chinese government, to return to Anderson’s point quoted at the beginning of this essay, a legitimacy Tokyo has lacked for so much of the postwar period because of its obvious subservience to Washington. Indeed, Hung Ho-Fung’s contention that Beijing has allowed the emergence of a new and influential class of entrepreneurs and financiers based in coastal China with ties to global capital – a class now too powerful to be thwarted – suggests that China may have become, in his words, ‘America’s Head Servant.’27

But if so, China will not be the kind of servant that Japan has been. Since the contours of the postwar Japanese political economy took final shape in the mid-1950s, Japan’s power-holders have acted, as we have seen, almost on auto-pilot, at least with respect to overriding national goals. They have coped with challenges and crises by attempts to recreate inherited certainties. Among other things, that meant deliberate efforts to stymie the growth of an independent class of entrepreneurs and business leaders who might balk at bureaucratic direction. Thus when Tokyo found itself faced with the choice of doing what it took to support a global capitalist order revolving around the US dollar or seeing that order collapse, it could and did take whatever measures were necessary, even if that meant depriving Japan’s households of any chance to earn real returns on their savings. The bureaucrats did not have to worry about being undermined by powerful capitalists with their own agendas.

China now faces much the same dilemma that Japan began to wake up to some 35 years ago: its economy is now so intertwined with that of the US and it has such a huge position in dollar markets that it cannot walk away from its support for the existing order without doing irreparable damage both to that order and to its own short- and medium-term economic prospects. But China’s leaders may be both more conscious of what they are doing than were Japan’s and – perhaps – less sure of their instruments of control. This may seem paradoxical since China is an authoritarian, one-party state while Japan is theoretically a democracy whose leaders must answer to an electorate. But the rise of provincial power centers that balk at Beijing’s orders, not to mention the swaggering coastal elite of financiers and entrepreneurs that Hung describes, suggests that the Chinese authorities may be less able to emulate the way their Japanese counterparts acted during several crises over the past 30 years: halt runs on the dollar with a few pointed phone calls. Indeed, the very reports that have surfaced in the international press of disputes among China’s power holders over currency and monetary policies point to underlying power struggles and raise questions over how and whether they can be resolved, particularly during periods of crisis.28

At the same time, the greater awareness by China’s leadership of what it is doing and why it is doing it may ultimately prove the critical variable in the perpetuation of American hegemony. While Hung’s coastal elite may act from time to time as a break on Beijing’s freedom of action, the state-capital nexus that has emerged in China over the past three decades displays, as Ching Kwan Lee and Mark Selden point out,29 a formidable capacity to discern threats to its collective control over China’s political economy and a proven capacity to neutralize them. Some of those threats clearly emanate from a Washington that while increasingly dependent on Chinese financial support seems at the same time to have China in its sights as the only serious long term challenger of American primacy in global affairs.

Japan’s political arrangements grew out of a millenium-long tradition of powerholders who pretended they did not exercise power or were doing so in the name of entities that were ultimately figureheads: emperors, shoguns, parliaments; that the policy makers’ right to make decisions that determined how others would live was grounded not in explicit, challengeable authority to adjudicate messy clashes of interest, but part of some ineffable order beyond the reach of politics. That supposed order served to cloak the real loci of power – and indeed forced denial on the power-holders themselves that they were exercising power. As Maruyama Masao wrote in 1946 about Japan’s pre-Occupation power structure, ‘It was unfortunate enough for the country to be under oligarchic rule; the misfortune was aggravated by the fact that the rulers were unconscious of actually being oligarchs or despots. The individuals who composed the various branches of the oligarchy did not regard themselves as active regulators but as men who were, on the contrary, being regulated by rules created elsewhere.’30 This fundamental political reality was not in the least affected by the legacy of the Occupation and Japan’s ostensible transformation from an oligarchy into a supposedly liberal capitalist democracy. Indeed, the American assumption for Japan of those powers by which a state is commonly recognized – the provision of security and the conduct of foreign relations – if anything served to exacerbate the denial by Japan’s policy makers that they had any real control over what they were doing. When they acted reflexively to support the supremacy of the dollar and of American hegemony, they were acting in the manner expected of them – and in the manner they expected of themselves.

China’s leaders are under no such illusions. They are perfectly aware of Marx’s comment to the effect that ‘men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please, that they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already.’ The circumstances under which China’s leaders are trying to make their own history, to return their country to the pivotal position in human affairs that its very name in Chinese implies (Zhongguo, ‘central country’) means accepting for the time being the financial hegemony of an unpredictable and even dangerous entity, a United States that has from the inception of their regime posed at least a latent existential threat. For the time being, they cannot do without the American market. But while they may find themselves, like their forerunners in Tokyo, forced from time to time to support the dollar, even at the cost of foregone purchasing power and a loss of control over certain economic and political outcomes, they do so with their eyes open.

R. Taggart Murphy is Professor and Vice Chair, MBA Program in International Business, Tsukuba University (Tokyo Campus) and a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal. He is the author of The Weight of the Yen and, with Akio Mikuni, of Japan’s Policy Trap.

This is a slightly revised and updated version of an essay that is being published in The Crisis This Time: Socialist Register 2011 edited by Leo Panitch, Greg Albo, and Vivek Chibber, copyright Merlin Press Ltd. (www.merlinpress.co.uk).

Recommended citation: R. Taggart Murphy, “A Loyal Retainer? Japan, capitalism, and the perpetuation of American hegemony,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 41-3-10, October 11, 2010.

Notes

1 Perry Anderson ‘Two Revolutions: Rough Notes’ New Left Review 61 January-February 2010, p. 93.

2 See B.C. Koh, Japan’s Administrative Elite Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989, esp. p. 254.

3 Andrew Gordon The Evolution of Labor Relations in Japan: Heavy Industry, 1853-1955 Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Press, 1985.

4 Brenner has defined capitalism succinctly as follows: ‘the capitalist mode of production distinguishes itself from all previous forms by its tendency to relentless and systematic development of the productive forces. This tendency derives from a system of social-property relations in which economic units – unlike those in previous historical epochs – must depend on the market for everything they need and are unable to secure income by means of systems of surplus extraction by extra-economic coercion, such as serfdom, slavery, or the tax-office state. The result is two-fold. First, individual units, to maintain and improve their condition, adopt the strategy of maximizing their rates of profit by means of increasing specialization, accumulating surpluses, adopting the lowest cost technique, and moving from line to line in response to changes in demand with respect to supply for goods and services. Second, the economy as a whole constitutes a field of natural selection by means of competition on the market which weeds out those units that fail to produce at a sufficient rate of profit.’ Robert Brenner, ‘The Economics of Global Turbulence’, New Left Review, 229, May/June 1998, p. 10.