The G8

Philip Seaton

The livelihood of Iwahara Yoshimi, a lettuce farmer living a few kilometers from The Windsor Hotel, was threatened by the G8

The G8 summit was a global media story. Leaders of the world’s richest nations joined by a growing group of invited leaders from all continents discussed the issues affecting the planet and their deliberations were relayed to millions of homes via the news media. However, Hugo Dobson has argued in his paper in this series:

Most media depictions of the G8 are sadly predictable to the degree that the reports for next year’s summits could probably be copied and pasted now. They tend to fall into one of two camps: it is either an evil behemoth of global capitalism irresistibly crushing all under foot … or it is regarded as an impotent, anachronistic and irrelevant talking shop at which what the leaders ate at dinner gets more press attention than their discussions and declarations. [2]

Part of the reason for these characteristics of media coverage is genuinely held concern over the consequences of globalization and neo-liberalism, of which the member states of the G8 have been the primary proponents. But they are also related to the news-gathering practices of the major news agencies. The constant need to be ahead of the competition on tomorrow’s news makes media coverage anticipatory rather than reflective regarding events fixed in the global calendar: events from the G8 summit to the Beijing Olympics are extensively hyped in advance but quickly forgotten. The anticipation often sets unrealistic expectations, and media coverage can be merciless if the event fails to meets expectations.

The

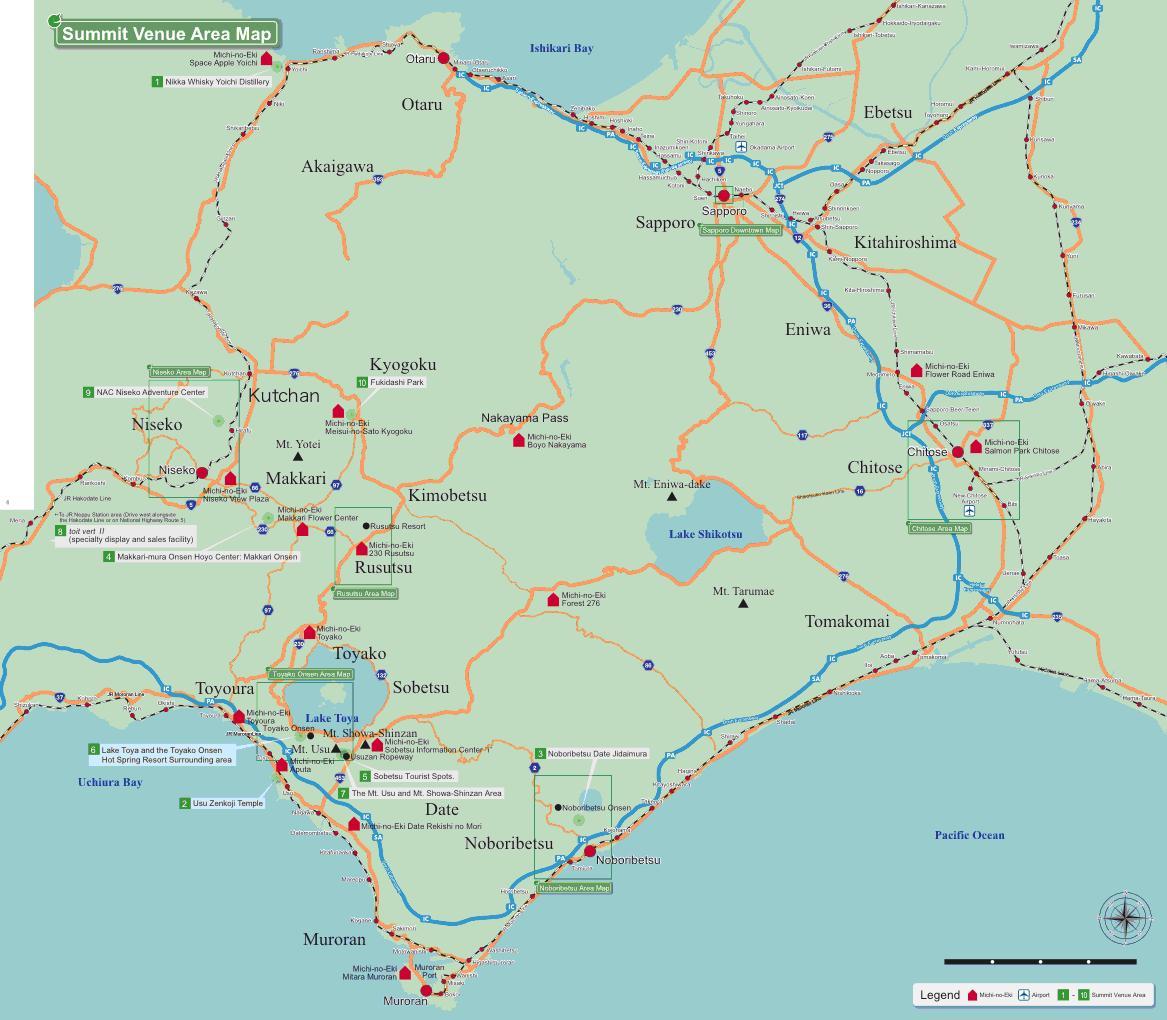

During G8 summits, journalists typically have a brief to cover primarily the leaders’ discussions. For reasons of security and convenience, they are herded into a media centre. The media centre for the Hokkaido Toyako Summit was located in Rusutsu, about 27 kilometers away from the Windsor Hotel. The journalists who “attended” the summit, therefore, had to rely for their information on the media centre monitors and print outs of official communiqués supplied by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Map, Hokkaido Summit Preparation Council

Some journalists ventured out of the media centre to get alternative angles, but given their distance from the summit venue and briefs to cover the political discussions, much reportage was limited to rewordings of official communiqués, in some instances with a critical angle to reassure the public that the media are watchdogs, not lapdogs, of the summiteers. In the absence of major political breakthroughs, always unlikely in the slow and painstaking process of multilateral diplomacy, headline-writers demanding more “newsworthy” angles can resort to spiced-up critiques of the summit, for example regarding the dinner – on which more later.

These practices of the international news media illustrate why coverage of the Hokkaido Toyako Summit (like other G8 Summits) tended toward the critical: summit coverage thrives on summit failings. This paper, however, examines an important exception: local media coverage in

Although

This was exemplified by the official line in

“As the host prefecture, we are resolved to provide the greatest possible cooperation and support to help bring the

Opinion polls indicated that Governor Takahashi spoke for many Hokkaidoites. People were generally in favor of the summit being hosted in

These generally positive sentiments were reflected in local media coverage of the summit, which rallied behind the official call “Let’s make the summit a success”. Even on issues with most potential for critical local coverage, such as security (discussed below), the local media was remarkably compliant. There were voices critical of the G8 to be heard – mainly in interviews with anti-globalization protestors, representatives of NGOs, or in alternative media. But once Prime Minister Abe Shinzo had made the decision in April 2007 to host the summit in

Furthermore, in the local media the main story was not so much the deliberations of the G8 leaders, but rather the effects of the summit on the host region as thousands of government officials, security personnel, staff from NGOs and journalists descended on their little corner of the world and made it the centre of global attention for a few days. The story of the lettuce farmer whose crop was being damaged by flights from a temporary heliport and whose story headed this paper epitomized this angle. Iwahara’s dilemma – wanting the summit to be a success while enduring inconveniences – was framed in terms of local costs vs. local benefits, or individual sacrifice for the collective good. A successful summit relied on the pluses outweighing the minuses, and the media played their part in emphasizing the positives; and through repeated comments wishing for the success of the summit, the media could even be categorized as playing a “mobilizer” role to bring civil society in line with official aims.

The

The analysis of

Time (in seconds) of summit coverage on the NHK news bulletins Marugoto News

In terms of the simple amount of summit coverage, Marugoto News Hokkaido’s coverage was over double the length of Newswatch 9, (4 hours 16 minutes compared to 1 hour 54 minutes), despite the program being 10 minutes shorter overall.

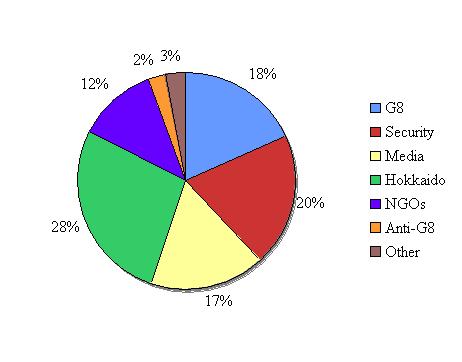

The programs were analyzed for content. The subject of coverage was categorized into seven broad themes as illustrated in the following table.

|

G8 summit |

The G8 political leaders and their spouses; other politicians involved with the |

|

Security/ Preparations |

|

|

Media/PR |

The International Media Centre; foreign journalists in |

|

|

Local reaction to the |

|

NGOs/ Alternative Summits |

Alternative summits; the activities of NGOs; reactions of NGO representatives to the deliberations at the main summit. |

|

Anti-G8 |

Anti-globalization or anti-G8 protests. |

|

Other |

Montages that covered many aspects simultaneously. |

The time given to these topics as a percentage of the total length of summit coverage in the program over the period is given in the following two charts. This first chart shows Marugoto News Hokkaido and indicates a fairly even spread of coverage between five categories – the main summit, security/preparations, media/PR, effects on Hokkaido, and NGOs – over the program’s 4 hours 16 minutes of coverage.

The second chart is for Newswatch 9 and shows that this program focused heavily on the main summit and security, which accounted for 86 per cent of the total of 1 hour 54 minutes of coverage.

The rest of the article focuses on these local perspectives with particular reference to NHK’s Marugoto News Hokkaido program, indicated by the following: (MNH + date). Other information is drawn from 23 minutes of summit retrospective on Sapporo Television, one of the five commercial channels in

Leaders and their Spouses

There is no need here to give a detailed summary of the summit proceedings, which were discussed in Hugo Dobson’s paper in this series. Instead, this section focuses briefly on a sub-theme in local coverage on NHK: the portrayal of leaders and their spouses as “visitors to

NHK Hokkaido’s presentation of the leaders as visitors to

But the “leaders as visitors” theme was particularly evident in coverage of the leaders’ spouses. Five spouses from overseas (neither Angela Merkel nor Nicolas Sarkozy’s spouses attended) were extended full Japanese hospitality by Prime Minister Fukuda’s spouse, Kiyoko. The six ladies were referred to as the “leaders’ wives” (shuno fujin) on NHK and their program of PR activities “reverted to the highly feminized photo opportunities of previous summits”.[8] They experienced Japanese traditional culture (kimono-wearing and tea ceremony, MNH 7 July), visited a market for local produce in Makkari village and the International Media Centre, where they donned Ainu clothing (see photo, MNH 8 July), and they planted trees and attended the J8 (Junior Eight) Summit (MNH 9 July). These activities were the subject of 2- or 3-minute reports on each of the days of the summit (and were then shown in abridged versions on Newswatch 9).

Security

The terrorist threat and the potential for disruptive, perhaps violent demonstrations by anti-globalization protestors mean that major summits require extensive security operations and choice of locale tends to be far from major metropolitan areas. As described above, both national and local NHK news gave comparable (in percentage terms) amounts of coverage.

The cost and nature of security had become a thorny issue by the beginning of the summit. The summit budget was 60 billion, of which half was for security. At a press conference on 1 July 2008 Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Taniguchi Tomohiko had to fend off questions from reporters about the budget, specifically why the cost of hosting the summit (excluding security) was nearly nine times the cost of the Gleneagles Summit in

Policeman at the IMC (Credit: Hugo Dobson)

For some citizens of

For many others the summit meant inconvenience. Coin lockers (for left luggage) in stations were sealed (MNH 3 July). Toyako resident and farmer Masada Kiyohara needed to apply for a pass so that he could drive from his house to his nearby fields, while 79-year-old Ohiro Satoshi had to rearrange his regular hospital appointments to avoid traveling during the summit period (MNH 7 July). Traffic restrictions were in place in central

In general, local news showed people stoically complying or putting up with the restrictions. If there were serious complaints about the summit security, they were not making NHK’s regional news. Quite the contrary, the regular reports about the security operation almost felt like a stern warning to the people of Hokkaido to comply with the security operation, or else.

Amid the generally supportive mood on NHK for the security operation, there were some more worrying aspects that raised a perennial problem in this age of a so-called “war on terror”: the extent to which security can be allowed to trump civil liberties. This was already an issue following the introduction of fingerprinting of all foreign visitors to

Incidentally, the security aspect was what deepened my own personal interest in the summit. In June I was stopped at

How ironic it was, therefore, that the biggest security scare of the summit was not caused by an Islamic terrorist, or even any of the “suspicious” foreigners stopped or detained at airports. Instead, it was caused by a Japanese man, Deto Takanari (69), who claimed that he was carrying a bomb as he boarded an Air Do flight to

On 10 July, the day after the summit, NHK Hokkaido joined in the collective sigh of relief that the summit had passed off without major incident. The 21,000 police officers from across

Covering the

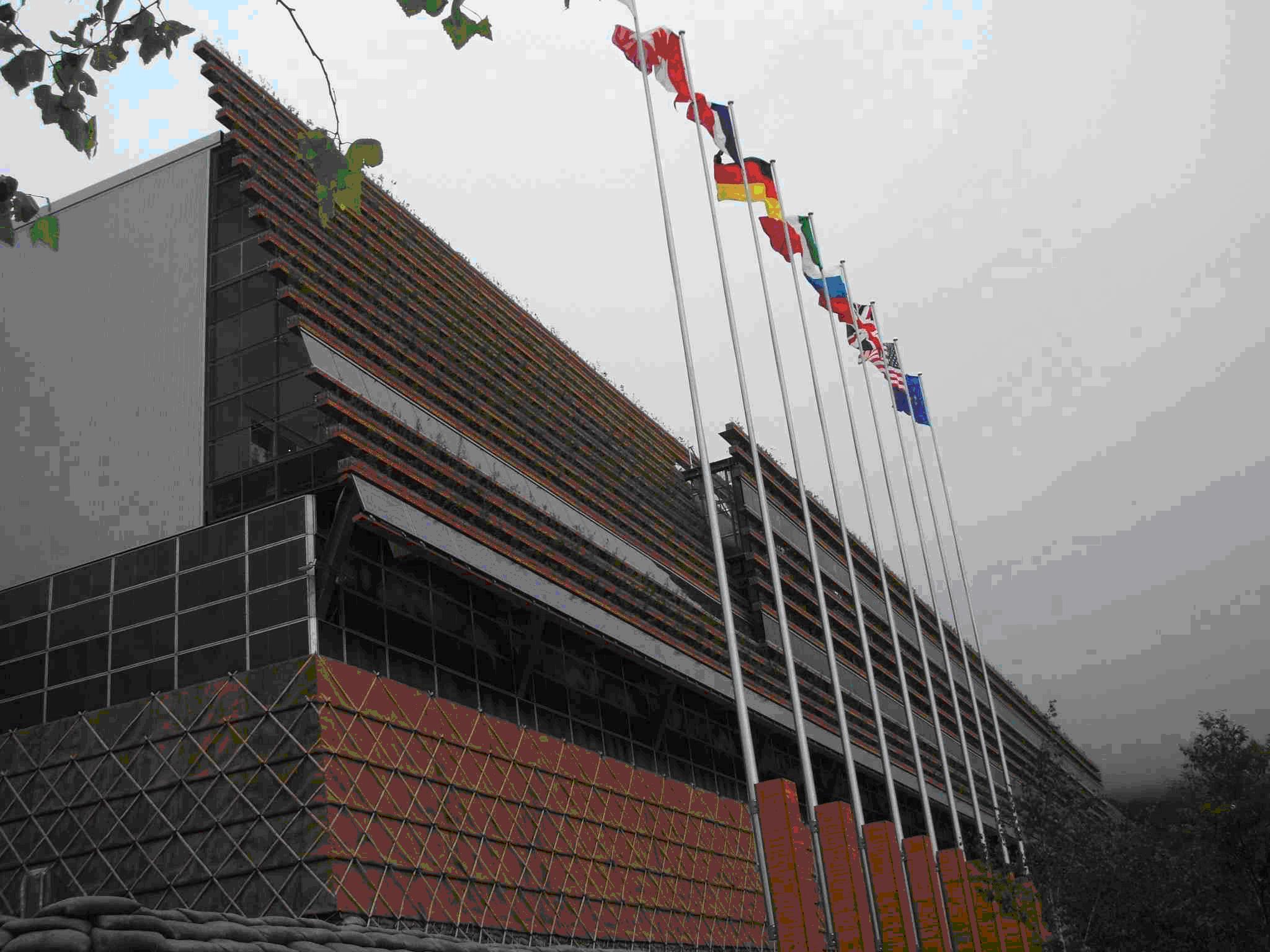

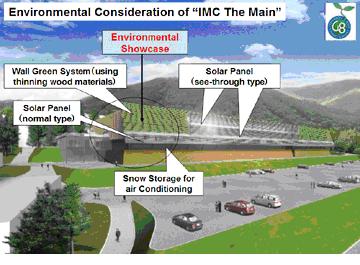

The G8 summit was reported to the world via the International Media Centre (IMC) set up in the car park of a ski resort in Rusutsu. IMC gained a lot of attention in its own right because of its environmental technologies and expense. The IMC budget was ¥5 billion, while communications infrastructure between Rusutsu and the summit venue in Toyako (which are 27 kilometers apart) cost 9 billion. By the benchmark of the Gleneagles Summit in 2005, this made IMC on its own much more costly than the entire ¥2.6 billion yen price tag (excluding security) for the 2005 summit. Given a number of pressing social issues in

NHK Hokkaido’s coverage of IMC, however, gave a different view. The coverage was mainly about the environmental technologies and the views of the foreign journalists covering the summit. In particular, rather than IMC being “disposable” it was “recycled” and “recyclable”. Rather than being “pulled down” it would be “dismantled” and 90 per cent of the materials could be used again (MNH 4 July). One angle that gained repeated coverage was the cooling system. It used snow to cool air, which was then conveyed around the media centre in a network of vents made from used cardboard boxes. The snow was visible beneath a glass floor to showcase this emission-free way of cooling a building, apart from the energy necessary to transfer 7,000 tons of snow into the basement of a building, that is. And while a snow cooling system (and the water’s subsequent use in air conditioners and toilets) may be innovative, it is hardly practical for most buildings.

Whether the environmental message was picked up enough by foreign journalists and people outside

Other reportage from NHK Hokkaido’s coverage hinted that the extensive PR efforts to market

These enthusiastic attempts to promote

The summit logo demonstrates clearly the importance of environmental issues for the summit. As illustrated in discussion of the International Media Centre, Japan tries hard to promote an environmentally-friendly image based on its development of clean technologies, for example in hybrid cars. Despite noticeable advances in recent years in popular environmental consciousness, such as the campaigns to use “eco-bags” and “mai hashi” (using one’s own chopsticks instead of disposable ones in restaurants), as Andrew DeWit argues in The G8 Mirage: The Summit and Japan’s Environmental Policies,

The choice of

The issue of the environment is one that resonates very clearly in

“As the food crisis began to bite, the rumblings of discontent grew louder. Finally, after a day of discussing food shortages and soaring prices, the famished stomachs of the G8 leaders could bear it no longer. The most powerful bellies in the world were last night compelled to stave off the great Hokkaido Hunger by fortifying themselves with an eight course, 19-dish dinner prepared by 25 chefs. This multi-pronged attack was launched after earlier emergency lunch measures – four courses washed down with Chateau-Grillet 2005 – had failed to quell appetites enlarged by agonizing over feeding the world’s poor.”[15]

The summit dinner was an easy target for attack by the international media given the discussions of rising food prices at the summit. In the article from The Guardian above, the dinner was framed in terms of the summit theme of global rises in food prices and poverty. The dinner was slammed as insensitive given hunger around the world. But on Newswatch 9 the dinner was uncontroversial: worth a brief mention but no more. In

In the international media, summit dinner critiques have become a cliché of summit coverage and partly reflect an inability to find other more substantive issues to report. Overall, the coverage of the summit dinner was the clearest example during the summit of local and international media basing their reporting on completely different assumptions.

Despite lagging well behind Europe and North America in the extent and vitality of its NGO sector,

NHK’s national bulletins gave relatively little coverage to these alternative events compared to regional news. For example, the Indigenous People’s Summit received only 40 seconds of coverage on Newswatch 9 (1 July) compared to nearly nine minutes (spread over 1, 3 & 4 July) on Marugoto News Hokkaido. Despite the importance of this event and the implications of the Japanese government’s declaration of Ainu indigenity just before the summit, this news would have been missed by all except the most observant viewers outside of

Cape Nosappu, the most eastern point of Japan: Just visible 3.7 km across the water is the Habomai Island group, part of the disputed

A deserted, dilapidated house in Yubari: symbol of economic woes in

Hosting the summit, it was hoped, would inject new life into the hotel, Toyako and

Given all the potential benefits – a boost to the local economy, publicity for

Through 1999 and the beginning of 2000, summit fever swept across

The obvious common themes suggest a “standard operating procedure” for summits hosted in

Within

The Lectern used by Prime Minister Fukuda: Empty lectern, empty statements?

Philip Seaton is an associate professor in the Research Faculty of Media and Communication,

With thanks to Watanabe Makoto, Hugo Dobson and ann-elise lewallen for all their helpful comments on a previous draft of this article.

Posted at Japan Focus on November 30, 2008.

Recommended Citation: Philip Seaton, “The G8 Summit as ‘Local Event’ in Hokkaido Media” The Asia-Pacific Journal,Vol. 48-7-08, November 30, 2008.

|

Article Series Index |

|

|

Alternative Summits, Alternative Perspectives: Beyond the 2008 G8 |

Philip Seaton |

|

The 2008 Hokkaido-Toyako G8 Summit: neither summit nor plummet |

Hugo Dobson |

|

Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous People’s |

ann-elise lewallen |

|

Lukasz Zablonski and Philip Seaton |

|

|

Philip Seaton |

|

|

Other Resources |

|

Andrew DeWit , The G8 Mirage: The Summit and Japan’s Environmental Policies |

References

[1] NHK, Marugoto News

[2] Hugo Dobson, “The Hokkaido-Toyako G8 Summit: neither summit nor plummet”, Japan Focus.

[3] Endo Seiji, “Global governance,

[4] Hugo Dobson (2007) The Group of 7/8,

[5]

[6]

[7] NHK was chosen primarily because it offered the best comparison between local and national news. There are five commercial channels on terrestrial television in

[8] Hugo Dobson, “Where Are the Women at the G8?”,

[9] The

[10] The

[11] Nakanowatari Takuya, “Chikyu ondanka no kanaria, ohotsuku-kai” in Osaki Mitsuru et al (2008)

[12]

[13] One stereotype given an airing on national television in February 2008 by a “variety” program about culinary, lifestyle and linguistic differences between

[14]

[15] Patrick Wintour and Patrick Barkham, “Just two of the 19 dishes on the dinner menu at the G8 food shortages summit”, The Guardian, 8 July 2008.

[16] Hasegawa Koichi, “The Development and Recent Trends of Environmental NGOs in Japan: Analysis from Social Movement Perspectives”, American Sociological Association, 2004, p. 1. (Accessed 24 November 2008).

[17] Dobson, The Group of 7/8, p. 85-6.

[18] See Zablonski and Seaton, “The

[19] See Peter Hajnal, “Civil Society at the 2001 Genoa G8 Summit”, online (Accessed 20 November 2008). On the death of Giuliani see, Jonathan Neale (2002) You are G8, We are 6 billion: The Truth Behind the

[20] Aoki Osamu, “Perceptions of Poverty in

[21] Washida Koyota (2007) Yubari Mondai (The Yubari Issue),

[22] A keyword search (31 October 2008) on Hokkaido Shinbun’s digital article archive using the words toyu (heating oil) and tonan (theft) turned up 30 articles in the period October 2007 to March 2008, each referring to hundreds or thousands of liters being stolen. The lack of articles prior to this period indicates heating oil theft was a new phenomenon in the winter of 2007-8.

[23]

[24] The

[25] The Japan Times, “G8 interest and apathy swirl around the ‘Tower of Bubble’”, 17 May 2007.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Julia Yonetani, “Playing Base Politics in a Global Strategic Theater: Futenma Relocation, the G-8

[28] See also Gavan McCormack and Julia Yonetani, “The Okinawan Summit Seen from Below”, JPRI Working Paper No. 71: September 2000.

[29] Yonetani, “Playing Base Politics in a Global Strategic Theater”, p. 88.

[30]

[31]

[32] Thanks to Lukasz Zablonski for attending this event.

[33] The