Jumping to the Right

Philip J. Cunningham

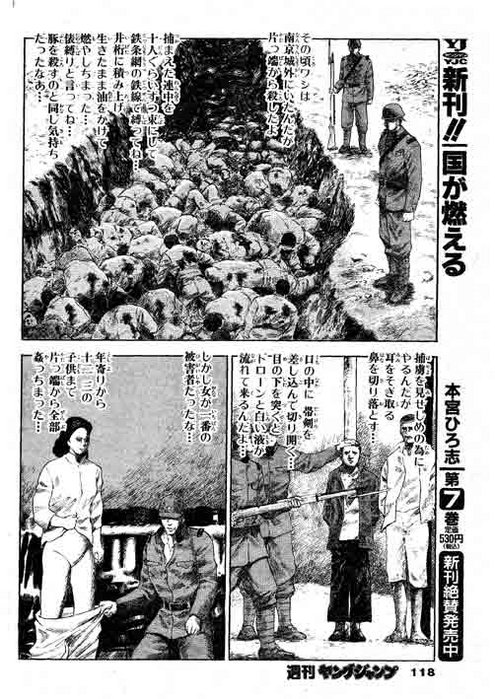

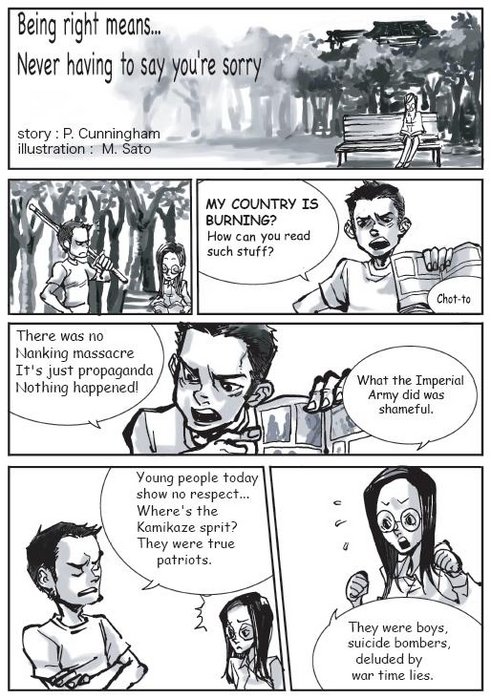

At first glance, the handful of Tokyo rightists who created a furor about a graphic scene of the Nanjing Massacre in two September issues of the popular manga magazine Young Jump Weekly are a surprisingly tolerant lot. They restricted their complaint to technical issues in “My Country is Burning” (Kuni ga moeru!) by Motomiya Hiroshi, the only remotely educational series in a popular weekly comic book, and ignored 400 pages of gratuitous sex, violence, scatology and gore that dominates this illustrated publication with a reported circulation of 2 million.

Illustrations from “My Country is Burning!”

This sends out a dubious signal to the nation’s youth: Violence is fine, as long as it’s entertaining and Doesn’t deal with sensitive historical issues. Thus the weekly’s graphic scenes of torture, murder, knife-fighting, body slashing, neck-snapping, automatic weapon fire, rape, sadism, bloody boxing, bombing, and smashing an iron skillet on a boy’s head –all from a recent issue– are business as usual. Where the violence starts to slack off, graphic sexual content helps rivet the attention of readers, whether it be big-busted bikini-clad teens, jokey cartoon nudity, perverts up-skirting schoolgirls on the bus, and so on. The first ‘clean’ issue of Young Jump Weekly, after the excision of “My Country is Burning” features three different stories involving characters urinating on other people.

The morally vigilant rightists instead turn their hypercritical gaze to a long-running historical comic series. The setting is Nanjing, the year 1937. Perhaps the single most controversial scene is that of a Japanese soldier posing for a photo next to a Chinese woman stripped of her clothes, disturbingly reminiscent of more recent wartime humiliation by US soldiers at Abu Ghraib prison.

The core of contention with the comic is, oddly enough, not the humiliated woman with the trousers around her ankles, but the Japanese man’s clothing, which was embellished with insignia to look like that of a soldier in Nanjing. The illustrated rendering is ‘controversial’ because it is based on an inaccurately captioned photo of probable Taiwan provenance, possibly a VD inspection scene at a brothel in Japan-occupied Taiwan, that appears in Iris Chang’s Rape of Nanking, a book deservedly lauded for bringing attention to an undeniable historical tragedy, but containing enough small errors to lead neonationalists to claim that the Nanjing massacre is a myth concocted by Japan-bashers. By tragic coincidence, Iris Chang took her own life at the time of this debate.

Never mind that news reports in contemporary Japanese and foreign researchers alike confirmed the reality of the Nanjing bloodshed, never mind that the Tokyo War Crime Trial and eyewitness accounts chronicled a massacre, never mind that ‘realistic’ comics of this sort use photos to model imagined historical scenes, never mind that the comic starts with a boilerplate disclaimer saying this is a work of fiction, etc.

Impugning the dignity of the Japanese soldiers who invaded China by suggesting they were something less than perfect gentlemen is the crux of the matter; the victims of rape and wanton murder do not enter the equation.

But that’s not all. The Tokyo-based right-wing critics, including some city assemblymen, who wrote Shueisha, the publisher, to complain about “My Country is Burning,” demanded and got suspension of the long-running Manga series and an apology from artist Motomiya Hiroshi.

Motomiya Hiroshi

The publisher is largely to blame for the blunt self-censorship. After all, there was no government intervention and the constitution protects free press. And it is ironic that the demand for apology comes from the very quarter that claims Japan need not apologize about its past. Nonetheless, the publisher in its November 25, 2004 issue of Young Jump Weekly further placated the rightists by promising twelve pages of mandated cuts and alterations if and when Motomiya’s manga is published in book form.

The Nanjing deniers make ludicrous demands on reality, which indeed raises the question why some 200 complaints (about one in ten thousand readers) should make publisher Shueisha cave in so shamelessly. The traditional fear of retributive violence epitomized by the chilling ideological attacks on film director Itami Juzo and former Nagasaki Mayor Motoshima Hitoshi come to mind, as does the more recent right-wing sound truck and Molotov cocktail attack on the home of Fuji-Xerox Chairman Kobayashi Yotaro, said to be in retaliation for criticizing Prime Minister Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine. Eschewing discussion of ‘sensitive Issues’ for fear of harassment from right-wing thugs is a salient aspect Japanese of political discourse today, essentially limiting the comfort of speaking out on the left, while expanding the comfort zone for the right.

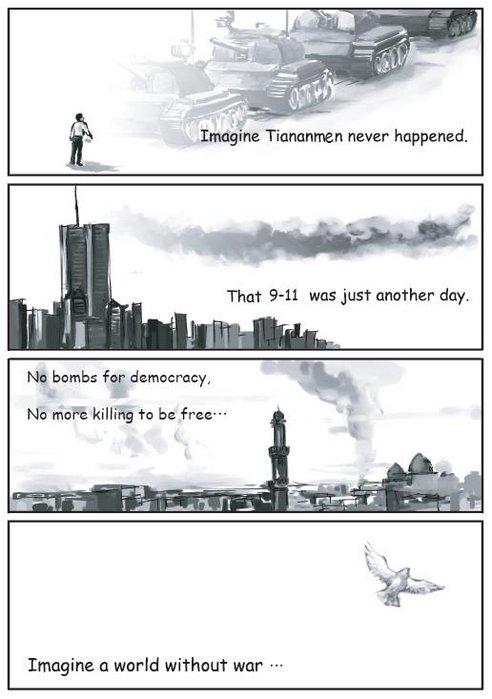

Like the Holocaust deniers, some of the Nanjing Massacre deniers are misanthropic eccentrics who have discovered a way to get attention and they appear to revel in it, even negative attention. But national politicians such as Tokyo Mayor Ishihara Shintaro also talk the talk, and major publications such as Sapio and Shukan Shincho provide ample space for similar rightwing revisionism. The implications of caving in to the rightists go beyond the loss of a good comic series. Every time Prime Minister Koizumi and other national politicians visit the Yasukuni Shrine to honor a dishonorable war, they authorize and expand the tactical space of the unrepentant militants. Yes, they want to be proud of their country, yes they want Japan to strengthen its military and take a more aggressive role in world affairs, but must they whitewash history and foment attacks against those who dare to disagree with their militant agenda?

No sooner does one politician make a partial apology to victims of Japan’s historic aggression, than another politician will claim that Nanjing never happened. No sooner do scholarly textbooks appear that recognize crimes committed by Japanese soldiers at Nanjing and elsewhere than “patriotic” textbooks are released white-washing uncomfortable aspects of the past. The national anthem dating from the war period is back, flag ceremonies mandated. Cosmopolitan Japanese increasingly travel to China and Korea to work, study and make friends, thus expanding peaceful relations while homeland-obsessed xenophobes find new ways to enrage Japan’s insult-weary neighbors. Koizumi may gain domestically when he visits Yasukuni Shrine where the spirits of wartime kamikaze bombers and convicted war criminals are said to reside, but it predictably enrages China, Korea and others who were victims of that war.

Even if Japan effectively buys a seat on the UN Security Council, Tokyo will still have difficulty gaining political respect commensurate with its economic power and technical know-how if it doesn’t have the courage to face up to legitimate complaints from its neighbors and acknowledge suffering caused by war and colonial atrocities.

Just before Motomiya’s series was suspended, one of his manga characters got in something as good as the last word. “What Japan’s army did in Nanjing cannot be covered up, no matter how hard you try.”

Philip Cunningham wrote this article while a Fulbright Research Fellow in Kyoto. He is professor of Media, Journalism and Communications at Doshisha University and the author of Tiananmen Moon: Inside the Chinese Student Uprising of 1989.

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Published February 1, 2005.