Chinese Plan for a Nanjing Memorial to ‘the Good Nazi’ Reopens War Wounds

By Peter Goff

The Nanjing Massacre remains a touchstone of China-Japan conflict nearly seven decades after the event. Now Chinese plans to honor John Rabe, a Germany citizen in Nanjing, for his efforts to protect Chinese citizens from slaughter have inflamed tensions with Japan over war and rare memory. The Chinese plan offers a rare example in the annals of warfare in general, and China in particular, of recognizing in a public and prominent way the achievements of a foreign national in a world that is dominated by nationalist icons.

The official Japanese response to the issues is emblematic not only of the inability to put war issues behind it but also of the fact that serious historians differ on many of the specifics of the massacre. The present article presents Chinese conclusions about casualties, notably 300,000 dead and 80,000 rapes. However, as David Askew has noted in “New Research on the Nanjing Incident,” several of the most exhaustive Japanese and international studies suggest that figures closer to 100,000 deaths may be more plausible.

With Chinese archives still closed, and with Nanjing deniers continuing to challenge the important research findings of critical Japanese historians, important issues pertaining to the massacre remain contested. Likewise, the number of lives saved by the actions of Rabe and other members of the international community remains moot. What is not in question is the fact that the Japanese military committed major atrocities at Nanjing. Is it possible that historians of China and Japan will eventually produce a common understanding of the events of Nanjing? If the recent history of East Asian nationalism is a guide, that will not be any time soon. The stakes, however, are high in terms of the peace and prosperity of Northeast Asia. Japan Focus

A plan by China to honour “the good Nazi”, a German who helped to save hundreds of thousands of civilians from Japanese troops, has reopened a dispute with Tokyo over its lack of atonement for the Second World War.

The Chinese authorities are drawing up plans for a museum dedicated to the memory of John Rabe, who defied the “Rape of Nanking” – a six-week massacre during which an estimated 300,000 Chinese were slaughtered by Japanese soldiers.

Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum figures for the victims

Honouring Mr Rabe gives China the chance to draw international attention to Japan’s wartime atrocities at a point when relations between the two Asian giants are fraught.

A card-carrying Nazi, Rabe was a China-based Siemens employee in 1937 when the Japanese stormed Nanking, or Nanjing as it is now known. His superiors ordered him to return home, but instead he sent his family back and established a “safety zone” in the city where he offered shelter to terrified Chinese.

Using his Nazi credentials, he and a small group of other foreigners kept the Japanese at bay, at considerable risk to themselves, and saved an estimated 250,000 lives.

Rabe wrote a 1,200-page diary that documented the killings and rapes in the city, information that was later used as evidence of war crimes.

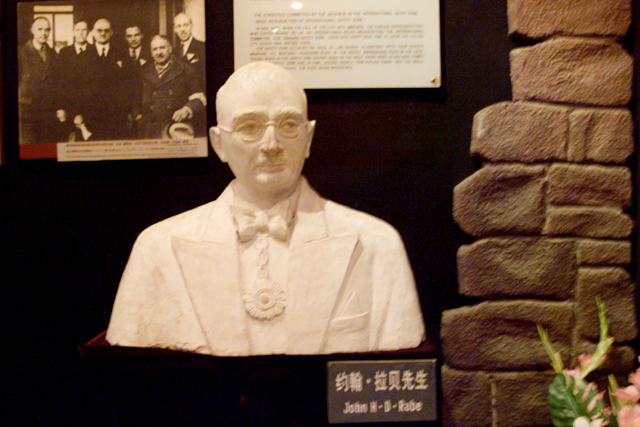

Statue of John Rabe at Memorial Hall of the Victims of Nanjing Massacre

The Japanese soldiers “went about raping the women and girls and killing everything and everyone that offered any resistance, attempted to run away from them, or simply happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time,” he wrote. “There were girls under the age of eight and women over the age of 70 who were raped and then, in the most brutal way possible, knocked down and beaten up. We found corpses of women who had been lanced by bamboo shoots.”

Chinese historians estimate that 80,000 girls and women were raped at the time.

“One was powerless against these monsters who were armed to the teeth and who shot down anyone who tried to defend themselves,” Rabe wrote. “They only had respect for us foreigners – but nearly every one of us was close to being killed dozens of times. We asked ourselves mutually, ‘How much longer can we maintain this bluff?’ ”

Beijing believes that Japan has never properly atoned for its atrocities.

Chinese anger is further fuelled by repeated visits by the Japanese prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi, to the Yasukuni shrine, which honours Japan’s war dead including some “Class A” war criminals held responsible for the massacre in Nanjing.

Entrance to Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum

Last week, China’s premier, Wen Jiabao, cancelled a summit with Mr Koizumi because “Japan won’t own up correctly to its history”. The shrine visits “seriously hurt the feelings of the Chinese people”, he said.

When the pair did finally meet at a signing ceremony of a regional meeting on Wednesday, Mr Wen snubbed the Japanese leader by ignoring his request to borrow his pen.

Several awkward seconds elapsed in front of television cameras before the request was loudly repeated and the Chinese premier pasted on a smile and handed over the implement.

There were mass protests in March outside the Japanese embassy and consulates in China after Japan published a history textbook that glossed over the wartime atrocities. Tensions between the neighbours are exacerbated by other thorny issues, including a territorial dispute over resource-rich islands in the East China Sea and Japan’s desire to become a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. China also fears what it sees as a growing nationalistic militarism in Japan.

“Part of the reason to honour John Rabe now is a response to Japan’s bad attitude,” Jiang Liangqin, a historian at Nanjing University, said. “For example, they honour the war criminals and have never properly said sorry. Some Japanese even deny the massacre took place. We know that Japanese often look down on Chinese and don’t believe what we say. Well here is a European who told exactly what happened. We want to bring the world’s attention to that.”

While the killings were going on, Rabe wrote to Hitler several times begging him to intervene but never got a response. He said later that being based in China meant he was unaware of Hitler’s heinous plans in Europe.

After the massacre Rabe lectured in wartime Germany about what he had seen and submitted footage of the atrocities to Hitler, but the Fuhrer did not want to hear about Japan’s actions. Rabe was detained by the Gestapo for a short period, denounced by the Nazis and barred from giving lectures.

In post-war Germany he was again denounced – this time for being a Nazi Party member – and was arrested first by the Russians and then by the British, but was ultimately exonerated following an investigation. He and his family lived in abject poverty, surviving on occasional care packages posted to him by the grateful people of Nanjing. He died of a stroke in 1950 at the age of 68.

“The people of China will never forget the good German John Rabe, and the other foreigners who helped him,” said Ma Guoliang, an 89-year-old woman whose parents were killed by the Japanese. “He saved so many people and yet at any time he could easily have been killed himself. He could have left, but he stayed with us. We called him the living Buddha of Nanking.”

Peter Goff is a Beijing-based journalist. This article was published in The London Telegraph, December 18, 2005. Posted at Japan Focus on December 23, 2005.