Cultural Flows Beneath Death Note: Catching the Wave of Popular Japanese Culture in China

Peter Goderie and Brian Yecies

Key words: China film policy, Death Note (2006), horror films in China, foreign exhibition in China, film piracy, internet piracy

Abstract

To better understand the controversy surrounding Death Note in the Chinese context, this article explores the historical precursors to the Chinese Communist Party’s ban on horror films, and examines the attitudes of Chinese students at an Australian university. The article also proposes a new viewpoint about how trade and popular presses in the West are attempting to understand China’s changing role in the global cultural industries.

The government of the People’s Republic of China has often been criticized for its policies regarding freedom of expression. Cinema in China has been central to this criticism, particularly with respect to the distribution of foreign films. This article uses a case study of the Japanese film Death Note (Kaneko Shūsuke, 2006) to advance current understanding of Chinese cinema found in important studies such as Chu (2002), Zhang (2004) and Berry and Farquhar (2006), and to show how new aspects of film-viewing are emerging among mainland Chinese audiences.

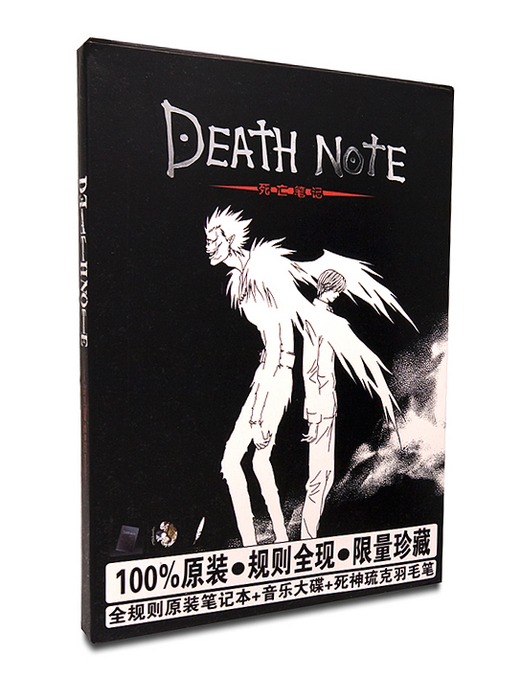

Though it was not licensed by any Chinese distributor and was eventually banned by the government, the Death Note franchise has gained popularity and notoriety within China. To better understand the controversy surrounding Death Note (see Figure 1) in the Chinese context, this article explores the historical precursors to the Chinese Communist Party’s ban on horror films, and examines the attitudes of Chinese students studying at an Australian university, some of whom had acquired the film illegally through internet piracy while they were still in China.

|

Figure 1. Packaging and contents of the “100% imported” Death Note DVD set, including a music CD, purchased from a small DVD shop on the main street of a Shanghai suburb in early 2009. |

Censorship, piracy and technology

Film, like many aspects of Chinese society, is heavily controlled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Even before becoming the governing body of China in 1949, the CCP tightly controlled information. Certain ideas have at various times been labeled taboo for both political and moral reasons: in the twenty-first century, censored topics have included pornography, the user-created content of websites such as LiveJournal and YouTube, the views of certain news media that are critical of the CCP, and information relating to Tibet, Taiwan, and the Falun Gong religion. Nominally, piracy is also one of these taboos, but intellectual property laws are not consistently enforced, particularly in outlying regions of China. In 2008, in a move that has been mocked by news media in the West, horror films were also declared off-limits, and any media containing horrific elements “specifically plotted for the sole purpose of terror” are now officially banned (General Administration of Press and Publications, quoted in Sun, 2008).

In the apparent age of the global village, this censorship would seem to be more difficult to achieve than ever before. Nevertheless, censorship persists, although not always in immediate or obvious ways. The CCP’s most infamous act of censorship in recent years has involved the group of policies which have been collectively nicknamed “The Great Firewall of China.” Instead of directly accessing the internet, Chinese internet users are connected to each other through a national intranet, which allows them to access only certain approved internet content (Dowell, 2006, p. 113). However, this firewall is easily bypassed by determined parties using a proxy server or any number of widely available programs (e.g., Psiphon, Tor, UltraSurf). Censorship thus becomes extremely difficult to enforce. According to some analyses, the CCP relies more on self-censorship and the fear of punishment than on actually blocking websites (Qiang, 2006; Hartford, 2000, pp. 259-260). Given the massive nationwide scale on which it has been implemented, this system could certainly claim some success. However, the psychological efficacy of this censorship is questionable in the case of university-aged students, particularly in light of the student interviews conducted for this study (discussed below).

The CCP has pursued similar censorship policies in the field of cinema. These policies have been proposed in the name of moral probity and political security, but they also exist to protect a heavily state-supported domestic filmmaking industry from competition with Hollywood over local exhibition. As with the Great Firewall, this censorship is often circumvented: a deeply institutionalized system of mass piracy, and the cultural acceptance of this piracy, allows Chinese consumers to enjoy all manner of forbidden media including software, music and films. The black market accounts for an estimated 95 per cent of all transactions involving audiovisual materials (Pang, 2004, p. 101). In some cities, pirated films can be purchased outside cinemas, and for less than the price of admission (Chu, 2002, p. 48).

The internet has become the ultimate distribution network for media pirates. Since 2008, China has been estimated to be the home of more internet users than any other country (Chao, 2008). As such, the limits of piracy are no longer spatial but technological, as access to illegal content is no longer dependent on the physical processes of printing, copying and transporting material goods. When audiences have such broad access to illegal products, policy alone is not sufficient to prevent the offending media from being seen. The determining factor in whether a particular film or program will be seen in the modern era is not distribution, but demand.

According to the Motion Picture Association (MPA), China has the highest piracy rate, for film and for other products, across the globe (MPA, 2004, p. 6). China has been infamous for years for piracy of all manner of intellectual property, most notably software, branded apparel and accessories such as handbags and watches. According to recent estimates, pirated goods in China are causing US$2 billion in lost profits per year (Rawlinson and Lupton, 2007, p. 88). Recent years have seen the proliferation of internet piracy through person-to-person filesharing, and through Chinese video-sharing websites such as ouou.com, where new episodes of American television programs have appeared, with complete Chinese subtitles, mere hours after their American release (Lin, 2007). Internationally, 80 per cent of all counterfeit goods seized by US customs in 2006 were en route from China (Wade, 2007).

Until the 1980s, copyright law was not officially recognized in China, and the CCP was itself a major distributor of pirate software (Massey, 2006, p. 232). After multiple bilateral agreements between the PRC and the United States in the 1990s, and particularly since China joined the WTO in 2001, China’s intellectual property laws have largely come to conform with the standards demanded of US copyright holders. But throughout most of China these laws have barely been enforced. US ire aside, institutionalized piracy remains prolific due to inconsistent enforcement of the law (Massey, 2006, pp. 232-233). The WTO has filed formal complaints protesting China’s lax enforcement of intellectual property rights (Wade, 2007). The defenders of Chinese intellectual property have also expressed concern, noting that while the Chinese market is only a small fraction of the global market enjoyed by international distributors, a Chinese company’s business is often entirely domestic. To Hollywood, the Chinese market represents the potential for additional profits, but to many Chinese copyright holders, success on the Chinese market is the only way to cover costs (Hood, 2005, p. 53). Even Zhang Yimou’s internationally successful Chinese film Hero (2002) was seen as a massive investment, which needed to be protected from domestic piracy. At the film’s premiere, there was one security guard for every three audience members, ensuring that absolutely no bags, cell phones, or hidden cameras built into eyeglasses or watches could be brought into the cinema (Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 212). At least twenty websites were blocked for attempting to host pirate copies of the film (Business Weekly, 2003).

Of course, this kind of aggressive enforcement of intellectual property rights is atypical, and in the unique case of Hero, the CCP’s motive was clearly protecting its economic and ideological investment in the film, rather than protecting intellectual property on general principles. The Japanese Death Note franchise presents an interesting comparison: in the case of state-sanctioned material such as Hero, intellectual property rights are enforced, so the only means of access is the legal one; but in the case of unsanctioned media such as Death Note, no legal avenue exists, and thus piracy is the only means of access.

Foreign films and the Chinese film industry

The CCP has long viewed cinema as a valuable tool for shaping public opinion. During the guerrilla war struggles in the years 1927-1950, it relied heavily on film to spread awareness of its cause in the cities. In the 1930s, it used its influence within the China Film Culture Society to produce numerous films depicting class struggle (Hu, 2003, pp. 79-81; Pang, 2002, p. 58). After 1949, it moved swiftly to monopolize the production and distribution of film under the government-controlled Chinese Film Corporation (CFC) and sixteen official production studios, and established the Beijing Film Academy (Chu, 2002, p. 46; Zhang, 2004, p. 201).

During the 1980s and 1990s, the CFC’s monopoly gradually gave way to a semi-capitalist network of privately funded studios and distributors. Beginning in 1984, the state-owned production studios were privatized and held accountable for their own profits and losses, but the state continued to dictate which scripts could and could not be filmed. Private regional distribution monopolies were authorized in 1993 by the Ministry of Radio, Film and Television (MRFT, later the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, or SARFT). Thirteen new private film studios were granted production licenses at the province level in 1995; more licenses were granted at the district level (along with licenses for television stations) in 1997 (Chu, 2002, pp. 45-46).

In this same period, the so-called “Fifth Generation” of Chinese filmmakers (including Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige, graduates of the Beijing Film Academy), began to attract international attention to the Chinese film industry, particularly through film festivals in Cannes, Berlin and New York. However, their success was not reflected in the industry’s earnings: in 1980, China’s population of just under 1 billion people purchased well over twenty billion tickets (Chu, 2002, p. 43). But by 1994, ticket sales had dropped to 3 billion tickets among 1.2 billion citizens (Zhang, 2004, p. 282).1 In addition to suffering from the proliferation of alternative viewing practices such as home video and piracy, Chinese films continued to suffer from the censorship of the CCP. The party still retained enough control to veto productions at any stage, even after it handed over the economic responsibility for its decisions to the filmmakers (Time, 1982; Chu, 2002, p. 45). Notable casualties included the August First, Changchun and Pearl River studios, which incurred the biggest losses of the 1990s (Zhang, 2004, p. 284).

In order to draw audiences back to cinemas, the CCP authorized a number of major policy changes in the 1990s. These included issuing the production licenses for the thirteen new private studios in 1995, encouraging private investors to claim the title of “co-producer” with an investment of 30 per cent of a film’s budget in 1996, and, most notably, giving the CFC permission to buy and distribute a limited number of imported films, under box-office-split deals, after 1994 (Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 205; Chu, 2002, p. 46; Zhang, 2004, p. 282). The decision to accept imports was a particularly radical change. American films had dominated China in the 1930s and 1940s, but since shortly after the ascension of the CCP to power in 1949, the local industry had been fiercely protected and almost all overseas films were prohibited from being screened (Hu, 2003, p. 20; Wang, 2007, p. 1).2 The Fugitive (1993) was the first Hollywood film to be endorsed by the CCP, in November 1994 on an experimental basis, and despite poor marketing and overpriced tickets the film earned a respectable RMB25.8 million (US$3 million) (Zhang, 2004, p. 282; Wang, 2007, p. 2; RMBGuide, 2006). Following this experiment’s relative success, the CFC authorized the distribution of up to ten imported films per year, dubbed into Chinese when appropriate (that is, when the imports were not imported from Hong Kong). Most of these imports far surpassed the success of The Fugitive, with True Lies (1994) and Titanic (1997) earning RMB102 million and RMB360 million (US$12.2 million and $43.5 million), respectively, in 1995 and 1998 (Wang, 2007, p. 2; RMBGuide, 2006).3

Simultaneous initiatives sought to strengthen Chinese production of films, rather than strengthen the box office as a whole. In 1995, to prevent imported films from dominating the box office, the MRFT announced that “mainstream melody” films – state-endorsed films which promote a politically correct Chinese worldview – should make up 15 per cent of all screen time of distributed films, with domestically produced films as a whole making up two-thirds of all screen time (Chu, 2002, p. 47; Zhang, 2004, p. 284). There was a five-year plan, dubbed the “9550 project”, to produce ten outstanding Chinese films per year from 1996 to 2000 (Zhang, 2004, p. 282). While regular Chinese film production would continue, these particular films would be released with the goal of promoting officially endorsed Chinese values and balancing out the American influence. For every Hollywood blockbuster, there would ideally be an outstanding Chinese film seen by the same number of people. The studios that were to make these films would compete for government subsidies totaling one-third of all investment in Chinese filmmaking at the time (Chu, 2002, p. 47).

Despite the limited number of imported films – domestic films outnumbered them each year by ten to one – the CCP has acknowledged that the imports still accounted for 60 per cent of all box office earnings throughout the years of the 9550 project. Other sources estimate this figure to be as high as 85 per cent (Chu, 2002, p. 43; Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 206). During this same period, only 15 per cent of Chinese films made any significant profit, and more than two-thirds could not cover their production costs (Wang, 2007, p. 2; Zhang, 2004, p. 284).

One of the outcomes of China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001 was renewed pressure from the United States to allow Hollywood greater access to the Chinese market. As a result, the maximum number of imported films was increased to twenty per year, with the intention of further expanding this figure in the future (Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 206; Chu, 2002, p. 53). In recent years, the Chinese market has become increasingly attractive to foreign filmmakers, with box office proceeds increasing by 25 per cent per year (Thompson, 2008). Despite China’s screen quota for international films, the MPA still considers China to be a lucrative developing film market (MPA, 2004, pp. 7-8). Hong Kong filmmakers in particular have been given incentives to take part in co-productions with China, since the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement of 2003 allowed such co-productions to apply for recognition as Chinese films rather than imports (Hammond, 2004).

Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) was a uniquely phenomenal success, appealing to a domestic audience, recovering its costs of about RMB250 million (US$30 million) and selling more tickets than Titanic (Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 211). It gained the support of both the censors and the prime minister, who diverted military resources toward the film and organized its premiere, which he attended personally, in the Great Hall of the People (Wang, 2007, p. 2). In fact, the film had already covered its costs from the presale of soundtrack and DVD distribution rights alone before its premiere (Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 212). Overall, the film earned US$177 million at the global box office, including US$54 million in the United States (Thompson, 2008a; Box Office Mojo, 2008). This US revenue was equivalent to thirty times the combined Chinese profits of all of the Hollywood films released in China that year (Hood, 2005, p. 53). This exceptional success story is illustrative of the Chinese cinema industry’s potential, as well as the kind of box office returns that the US industry might dream of in the Chinese market.

However, in a market of over one billion people, even Hollywood films are still achieving only one-tenth of their anticipated profits (MPA, 2004, p. 6). The Chinese box office earnings of Titanic, at RMB360 million (US$43.5 million), only accounted for 2 per cent of the film’s total earnings worldwide (Wang, 2007, p. 2; Box Office Mojo, 2008).4

Further, these low profits of Hollywood films in China are only earned by films that have received official permission to be screened. Those films that do not receive state approval can make no profits through legal channels, regardless of the demand for them in the Chinese market.

Death Note

The underground popularity of Death Note in China helps us to understand how transnational cultural flow is circumventing the new modes of Chinese censorship. In particular, local practices involving online media piracy have enabled Death Note fans to maneuver under the radar of the SARFT (State Administration of Radio, Film and Television), which issued a rather widely publicized ban on the franchise, and circumvent the wider ban issued by the GAPP (General Administration of Press and Publications).

|

Figure 2. Death Note DVD available in China. |

The entire Death Note franchise has gained popularity and notoriety the world over,5 but of particular significance here is the two-part film version of the original story. The first Death Note film earned US$25 million in Japan, and the sequel almost doubled that figure at $43 million, staying at number one in the Japanese box office for four weeks (Elley, 2007). In the United States, more than ten film companies expressed interest in producing a remake, with Warner Bros. eventually acquiring the rights and commissioning a script in 2009 (The Star, 2007; Fleming, 2009). In South Korea, the Death Note spin-off film fared better in its opening weekend than did the contemporary Oscar winners Atonement (2007), Juno (2007) and No Country for Old Men (2007) combined, all of which opened the same weekend (Paquet, 2008). The franchise has also sparked its share of controversy in countries other than China. There have been many accounts of American children making death-lists in the style of the series (Anime News Network, 2007; 2008a; 2008b; 2008c). In a Belgian case dubbed the “manga murder”, Death Note was linked to a possible real-life murder or medical prank: parts of an unidentified human body were discovered along with notes referring to the franchise’s main character, Kira (La Denière Heure, 2007).

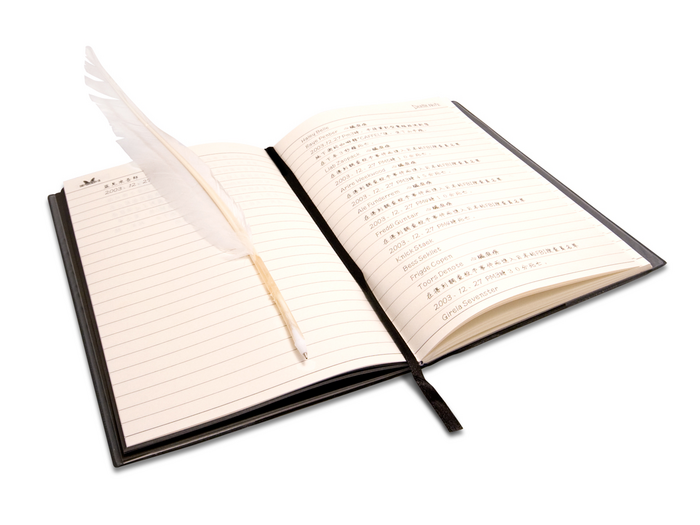

Death Note tells the story of a young genius named Yagami Light. At the beginning of the series, a bored death-god named Ryuk randomly hurls a magical notebook (see Figure 3) out into the world. The notebook is discovered by Light, who learns that if a person’s name is written in the notebook, that person will die – but when the writer eventually dies, their soul will belong to Ryuk. Despite the cost, Light decides that the death note has the power to save the world from evil, and he begins writing down the names of evildoers all over the world. Most media in the Death Note franchise follow Light’s conflicts with international law enforcement – because as soon as people realize that these mysterious deaths are actually murders, then the hunt for the killer (aka “Kira”) begins.

|

Figure 3. The notebook and accompanying quill pen included with the Death Note DVD set available at unofficial DVD shops in China. The black notebook pages show the instructions for using the book. |

Generically, Death Note could be identified as a horror film, however many fans find that the mind-games and superhuman feats of deduction (reminiscent of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes) are the real focus of the story and the source of the dramatic tension (e.g. Elley, 2007). Thematically, the franchise explores the inability of legal and political authorities to regulate society, the morality of capital punishment, and the corrupting nature of power. While various characters express contrary opinions on Kira’s vigilantism, it is generally implied in the stories that by promising his soul to Ryuk (see Figure 4) in exchange for the death note, Light becomes evil. The actions of the death god Ryuk in the franchise’s various endings also play to human concepts of justice and fairness, in a universe that is neither fair nor just.

|

Figure 4. Ryuk. Image courtesy of Madman Entertainment. |

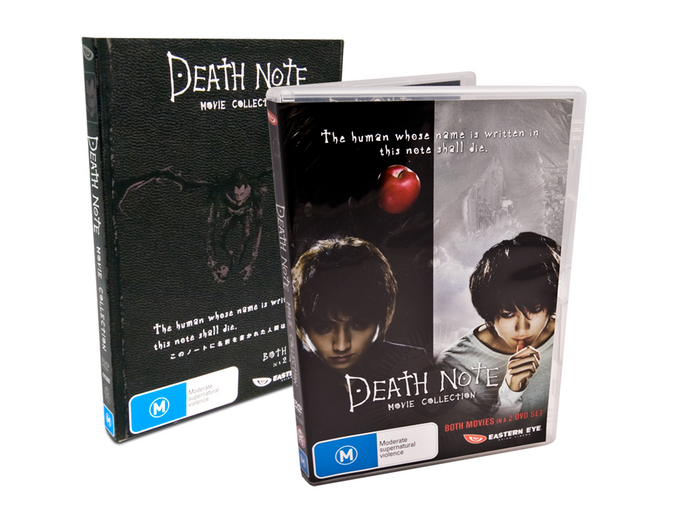

As is typical of the Australian distribution of Japanese anime and manga franchises, Death Note only began to be distributed officially in Australia long after its success elsewhere. The DVDs (see Figure 5) were distributed by Melbourne-based Madman Entertainment, released gradually between February 2008 and November 2009 (Madman, 2009). The anime series also began free-to-air distribution on ABC2 in 2008. Almost all consumption of Death Note in Australia up until that point would have involved piracy, likely conducted through the controversial but ubiquitous practice of “fansubbing”, the free distribution of pirated episodes including fan-made subtitles.6 Thanks to the internet, fansubs are often in global distribution within a matter of days after an episode has premiered on Japanese television. And while they are not technically legal, in most cases no legal alternative exists until months or years later when a show is licensed by an international distributor such as Viz or Madman.

|

Figure 5. The Australian double DVD release of the live-action Death Note series. The saying “The human whose name is written in this note shall die” appears on the external front cover of the packaging as well as on the front of the DVD case. |

Though Chinese-language versions of the Death Note manga and anime have been legally published in Taiwan and Hong Kong, neither have been released in mainland China through any official channels. The manga was distributed by Taiwanese Tong Li and Hong Kong–based Animation International Ltd., while the anime aired on Hong Kong’s TVB Jade and on the Animax channel in both Hong Kong and Taiwan. All of these versions are written in traditional Chinese script, not the simplified script used in mainland China, and in some cases are dubbed into spoken Cantonese. The live-action movies were also aired with traditional Chinese subtitles in these regions – in fact, the first film was the most successful Japanese film in Hong Kong in ten years (Comi Press, 2006; Elley, 2007) – but they were certainly not among the limited number of foreign films imported by the Chinese Film Corporation.

Death Note’s Japanese publisher, Shueisha, has not gone to any great lengths to sell its product in China,7 and in fact has been quoted as publicly announcing “we did not give any license to publish Death Note in China for anyone. All of [the Death Note products in China] are pirated” (China Information Agency News, 2007). The act of piracy does not seem to be the real concern in China, though. The entire Death Note franchise is now contraband on two separate counts: it is necessarily pirated, in the same manner as most Australian Death Note products have been up until recently, and more importantly, it has been recognized by the Chinese government as obscene and dangerous. Considering China’s long-standing reputation for officially ignoring (or even endorsing) mass piracy, there is nothing redundant about banning one particular variety of pirated material.

During the early days of the Death Note franchise as a serial manga, it created controversy in the Chinese city of Shenyang when school students apparently began writing teachers’ names in replicas of the Death Note notebook (Anime News Network, 2005). As the series’ popularity grew, so did the moral panic, with local Chinese media identifying further examples of students keeping death lists in the style of Death Note in Wuhan and Nanning after the release of the anime and films (Chutian Metropolis Daily, 2007; Yahoo! Japan, 2007). The Nanning case appeared on national television. One newspaper interviewed students, parents and shop clerks in Shenzhen, generating still more controversy by quoting students who proclaimed that Death Note’s appeal lies precisely in the fact that it is “scary” (a sentiment not generally shared by older fans), and one clerk who admitted to selling about seventy Death Note notebooks each day, typically to elementary and middle school girls (Shenzhen Daily, quoted in Comi Press, 2007).

In May of 2007, concern about the proliferation of Death Note merchandize reached new heights, as bookstores and newsstands located near schools in Beijing were raided by authorities looking for illegally published horror stories, citing “the physical and mental health of young people” as the reason (Reuters, 2007). Local media made special note that adaptations of Death Note were the targets of the crackdown (Xin Jing Bao newspaper, 2007, cited by Reuters). The raids quickly spread to smaller regional cities. Throughout May of 2007, officials in the city of Lanzhou reportedly received numerous death threats from students in response to the manga’s confiscation (Zhou, 2007). By June 2007, one month later, the General Administration of Press and Publications (GAPP) announced that “China has confiscated 5,912 Death Note books, 1,364 horror CDs and DVDs and 11,930 other illegal horror books across the country” (People’s Daily Online, 2007). A new type of crackdown on foreign cultural products had begun.

The controversy over Death Note in China came to a head in February of 2008, when the GAPP announced a national ban on all media containing elements of horror, particularly “alien-looking” characters such as demons, monsters or ghosts (Yunlong, 2008).8 The decision, like many other censorship initiatives in China, was mocked by various Western news publishers.9 The British Telegraph reported that, following Steven Spielberg’s withdrawal from the promotion of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, his “most lovable creation”, E.T., was being targeted by Chinese officials seeking revenge (Telegraph, 2008). The ban was covered in Reuters’ “Oddly Enough” section (“it’s news, but not, you know, the important kind”), and on the internet news site Slashdot the story was listed as befitting the “won’t someone think of the braaaaaains” department, with the tags “censorship”, “movies”, and “idiots” (Reuters, 2008; Slashdot, 2008). Following these sorts of reactions, the GAPP issued a defensive statement that family-friendly media such as E.T. (1982), Harry Potter (2001) and Shrek (2001) would not be targeted by the ban, only films that are “severely harmful to minors’ physical and mental health” (China Daily, 2008a).

Student Interviews

The uniquely difficult challenge of policing the spread of illicit material through internet piracy is surely a factor in the ubiquity of such practices as person-to-person file sharing, but it is not a complete explanation because it does not address the demand for pirate media. To gain a better understanding of this trend, this study investigates the attitudes, beliefs and consumption patterns of several Chinese students studying at an Australian university. Participants were asked about their knowledge and opinions of horror films, and given the opportunity to watch the first live-action Death Note film (Kaneko Shūsuke, 2006). While the franchise is forbidden in China, the film is readily and legally available to Chinese students while they are studying and living in Australia. As noted above, the franchise was released in Australia between 2008 and 2009, by Madman Entertainment

Chinese students in their early to mid twenties, in particular, were selected for this study because of their anticipated familiarity with circumventing censorship control mechanisms. According to general global estimates, young adults (ages 16-24) make up 39 per cent of all pirates, and 58 per cent of internet pirates (MPA, 2004, pp. 11-12). University-age students have also been the major targets of several recent anti-piracy campaigns in China (MPA, 2008a; MPA, 2008b). However, these participants are not a representative sample of any larger population. They form a case study, which can be used to illustrate how some individuals might negotiate the issues of freedom of information and intellectual property.

Five participants were first interviewed individually and asked to discuss their opinions of films, especially horror films, and to compare their experiences of watching films in Australia and China. The interviews were recorded for later review and analysis. When these individual interviews were completed, the five participants and two others were invited as a group to watch the Madman DVD release of the first Death Note film. These seven participants then took part in a group interview discussing what they liked about the film, whether they felt it deserved to be banned, and why. The participants’ descriptions of their film-watching habits were generally supportive of previous research: while some students owned legally bought DVDs, most chose piracy (particularly via the internet) as their preferred method of film consumption. Several participants felt that cinema tickets were too expensive, particularly if they wanted to see a popular new film. The one student who preferred to see a film in a cinema, ‘Taylor’,10 still only went to the cinema about four times per year – and even this is well above the average for a Chinese cinemagoer in recent years (USC US-China Institute, 2008; Coonan, 2008b; Screenville, 2008). None of the participants had been to a cinema at all during the time they had spent in Australia, nor were they planning to do so.

Of the many films that participants suggested were among their favorites, only one film was Chinese (Hero). Some participants did sometimes enjoy Chinese films, but they generally preferred foreign films. Most of the films students mentioned by name were Hollywood films, although ‘Ray’ and ‘Taylor’ enjoyed Japanese cartoons, and ‘Naomi’ was a fan of Korean love stories. As to which films they deemed worth buying on DVD, ‘Wendy’ and ‘Naomi’ pointed out the benefits of those with professionally translated subtitles and multiple soundtracks: DVDs of foreign films, they argued, were more attractive than Chinese films not simply because of the films themselves, but because the degree of control a viewer has when watching a DVD is particularly appealing for foreign language films. They also liked films whose subject matter was “unreal” or “not close to our real life,” a trait that they associated more with foreign films.

Most of the participants were familiar with Death Note, to varying degrees. Of the seven students, ‘Roger’ and ‘Wendy’ had seen the Death Note film in China, and ‘Roger’ and ‘Ray’ were fans of the manga and anime versions. ‘Roger,’ ‘Wendy’ and ‘Ray’ all said that they had acquired Death Note in its various forms via internet piracy in 2006 or 2007, and had no trouble doing so. The other students had heard of the series through the Chinese news media. ‘Taylor’ had seen the books for sale in China, but had not purchased them.

Those who had consumed Death Note products before had experienced no trouble obtaining the material online, though ‘Ray’, ‘Matt’ and ‘Steve’ all agreed that the material would be more difficult to find after it had been banned. Still, ‘Steve’ maintained that, using the popular person-to-person file-sharing protocol BitTorrent (or “BT”), it would probably be far from impossible. ‘Ray’ estimated that the difference would simply be a matter of how long it would take to find the material, perhaps an increase from five minutes to half an hour due to government attempts to remove the material from popular Chinese servers.11

Beyond accessing Death Note, participants generally seemed comfortable and familiar with piracy. ‘Ray’ had participated in retail piracy since the late 1990s, and ‘Steve’ had been downloading films since around 2003 – coincidentally, soon after ADSL became available and affordable in China (CNNIC statistics, 2002-2009). ‘Roger’ almost always chose to download films rather than go to the cinema, again citing overpriced tickets. Other participants had all seen pirated films, with ‘Naomi’ and ‘Taylor’ each citing their families’ DVD and VCD collections, and ‘Wendy’ describing her experience of seeing a downloaded version of Death Note with her friends. When the group was asked if they would be upset if piracy became impossible, ‘Steve’ laughed and stated emphatically, “of course, my life would be ruined!” However, none of the students felt that they were taking any legal risks. ‘Ray’ even commented that “there’s still no laws in China to punish people”. While this is not exactly true (and ‘Ray’ did later concede “maybe there are laws, but I don’t know about it”), participants believed that consumers of pirate goods are rarely punished, while the distributors of the pirate goods are dealt with severely. As an illustrative example, the first citizen of Beijing to be imprisoned for piracy was arrested after ten thousand DVDs were seized from his store in December of 2007 (Coonan, 2008a). The focus on distributors rather than consumers of piracy appears to be a key feature of the Chinese government’s attitude toward piracy (and it is supported by the action plan from the State Office of Intellectual Property Protection of the P.R.C, 2006, section II: Law Enforcement). However, ‘Steve’ observed that in less centralized online piracy networks such as BitTorrent, this mode of law enforcement becomes obsolete, as all users are small-scale distributors.

Opinions on the Death Note film were divided evenly within the small group who took part in this study. Some participants enjoyed it so much that they were disappointed that we were not going to watch the sequel that same night, while one participant, ‘Matt’, found the film generic, boring, and unnecessarily long.

All of the participants insisted that the film was not a “horror film”. They defined a horror film as a film made with the intention to scare its audience. (Similarly, the GAPP’s ban on all media containing horror described a horror film as “specifically plotted for the sole purpose of terror”; China Daily, 2008a.) The participants did not feel that the creators of Death Note had this intention. ‘Wendy’, who had already seen the film in China, repeatedly praised the film for its interesting use of supernatural elements like the death god Ryuk, and the death note itself. “I don’t like horror movies,” ‘Wendy’ said. “They scare me. I can’t sleep well.” However, she enjoyed Death Note and encouraged her friends to see it and take part in this study.

For the purposes of this study, the following elements in the film were identified as potential sources of “horror”: the physically monstrous Ryuk, the supernatural power of the death note, and Light’s willingness to kill. The participants had something to say about each of these elements.

When asked, “Is Ryuk scary?”, all of the participants said no, and some laughed. As Ryuk is invisible to all characters except Light, he is played mostly for laughs; in one quiet scene, Ryuk appears suddenly and loudly, dangling from the ceiling, only to be told by Light to “shut up”. Ryuk also has an inexplicable obsession with apples. Aside from this comedic element, ‘Taylor’ described Ryuk as “just the god of death”. ‘Taylor’ also pointed out that, while Ryuk is an ugly creature who wants people to die, he doesn’t care whether people are moral or immoral, or who wins or loses. ‘Ray’ said that Ryuk would inevitably “be the winner anyway” regardless of what happens between the human characters, as Ryuk’s only goal is to be entertained. He is mostly a plot device, and (at least in the first film) he never kills anybody or makes any other attempt to change the course of events beyond dropping the death note in the first place.

The details of why death notes exist and how they work are further fleshed out in the sequel and parts of the animated series, but in the first film the death note simply appears mysteriously, without a proper explanation for why it exists or where it came from. ‘Matt’ insisted that the premise was “bad science fiction”. Other participants commented that the unexplained supernatural elements were simply “mysterious” or “interesting”. Overall, the participants felt that the unexplained supernatural elements of the film showed that it is “not realistic” and “cannot be true”, which they also felt made it less horrific.

The film’s main moral conflict involves the prospect of a single person with the authority to carry out capital punishment, and that person being willing (if not eager) to exercise this authority. It is notable that the film opens with the supernatural killing of a criminal who has escaped legal punishment – the death note succeeds where the legal system has failed. The participants were unable to come to much consensus as to whether Light’s actions in the film were morally justified. Some students identified with Light’s goal of ridding the world of crime, and felt that Light had a fair sense of justice, while other students insisted that his character was clearly intended to be a villain due to his ruthless vigilantism. Most of the students could agree, however, that Light’s shift from idealism to corruption as he gained more power was the intended moral of the story, highlighting the relationship between authority and tyranny.

Most participants also agreed that, between L and Light, children would have a hard time deciding which character was a “good guy” and which was a “bad guy.” In fact, even the adults in this study had trouble deciding this. ‘Naomi’ and ‘Wendy’ felt that the game-like competition between the two characters could lead children to associate killing, or violence, with fun. ‘Steve’, a fan of video games, took issue with this claim, and drew an ironic comparison to similar controversies over the interactive violence of video games, but he defended the right of individuals to decide for themselves what media they want to consume. For the most part, the participants felt that Death Note was probably unsuitable for children under the age of about sixteen. However, all of them agreed that many children would be curious about the films, possibly because they were forbidden. ‘Taylor, ‘Ray’ and ‘Naomi’ felt that children about ten years old would often be familiar with “worse” stories than Death Note, which contain more violence and gore (these features are mostly absent from Death Note – the victims simply drop dead after their names are written in the book).

Conclusions

The interviews suggest that internet piracy is not an isolated phenomenon, but exemplifies a wider trend of liberalization among Chinese youth. The openness of Chinese students to foreign media, and their critical approach to both domestic censorship and international concepts of intellectual property, embody a type of free thinking similar to some of the ways that media are understood in North America and Australia. Their views correspond with China’s transformation from a politicized mass culture to an individualistic, consumerist state (Palmer, 2006, p. 145). The consumption of forbidden foreign media thrives despite the Chinese government’s censorship policies; audiences pay little heed to state edicts that the censored material is harmful to the morals of society. Young people want to learn about foreign culture through film and television, and one of the simplest and most direct ways they can do so is through piracy, either via the internet or the black market. Criminality and law enforcement did not even seem to be an issue to this study’s participants in terms of their everyday media practices.

Considering the history of piracy in China, their beliefs are perhaps unsurprising. However, the nature and impact of the piracy of foreign films in China have changed. Piracy of Hollywood films in China might have been seen as a positive force for foreign film producers twenty years ago, as it would have created demand and increased pressure on the Chinese government to open up the Chinese market to imported products (this is to say nothing of the impact of piracy of other more available products, nor of the export of pirated material produced in China). But now that some legal alternatives to piracy exist, the black market harms both the domestic and the foreign film industry, and the choice to consume pirate material challenges those who are legally producing and distributing the content.

The participants in this study were fairly comfortable discussing their piracy habits, but more deviant activities cannot be discussed quite so openly. When one participant jokingly raised the subject of the banned Falun Gong religious movement, the other participants were quick to distinguish between the downloading of illegal material relating to Falun Gong, and their illegal consumption of Death Note. The CCP’s stance on Falun Gong has been made abundantly clear by a long term media campaign in China, denouncing it as an evil cult. While students did not care about the illegality of Death Note, they insisted that they would never download material relating to Falun Gong. This difference can easily be attributed to different levels of emphasis in news reports about the two topics, and to the inconsistent or lackluster enforcement of intellectual property laws, but it is an interesting comparison nevertheless.

The participants found the Death Note film perfectly suitable for their own consumption, but they did feel that it was unsuitable for the children whom the Chinese media identified as Death Note’s fans. This raises a familiar question: should China adopt a ratings system (and thereby legalize content which is currently banned) similar to that of Australia’s Office of Film and Literature Classification or the Motion Picture Association of America? The idea has often been suggested, and in fact at one point it was announced that such a system would be implemented in 2005 (Smith, 2008, p. 134). But the GAPP currently maintains that such a system would be “too sensitive for the general public”, and that allowing products such as Death Note or Ang Lee’s Lust, Caution (2007) to be released in their entirety to any audience would be nothing less than legalizing the distribution of dangerous, immoral material (Mingxin, 2008). However, even if one were to concede that Death Note and other banned media are dangerous, the brute-force censorship of an outright ban, accompanied by the confiscation of all horror films, can be easily overcome through internet piracy anyway. While a ratings system does nothing to make inappropriate films more difficult to see, it gives audiences a clearer understanding of what to expect. It also encourages an informed choice of how to self-censor on the part of both filmmakers and audiences: the former because filmmakers can set out to achieve particular ratings as a way of targeting particular markets, the latter because such discrete categories might encourage a deeper awareness of which kinds of content children are exposed to. The prospect of making an informed decision appeals particularly to the liberal mode of thinking displayed by participants in this study.

This liberalism may surprise some in the West who continue to see China as a totalitarian state, but these students’ attitudes towards material such as Death Note are contributing to China’s impact on cultural industries around the globe. Further research, possibly involving a larger cohort of overseas Chinese students studying in different geographic locations, might lend more weight to this conclusion.

Peter Goderie teaches part-time in the Bachelor of Communication and Media Studies degree program at the University of Wollongong, and is an avid role-playing gamer. In 2009, he received a first-class Honours degree for his coursework and thesis, which examined Joss Whedon’s internet miniseries, Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog (2008), as a point of intersection between the culture industry and the gift economy. Peter researches how fans value their media, and the radically different ways that legal and political authorities assess this value.

Brian Yecies is Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies and the Co-convenor of the Bachelor of Communication and Media Studies degree at the University of Wollongong. His research focuses on film policy, the history of cinema, and the digital wave in Korea. He is a past recipient of research grants from the Asia Research Fund, Korea Foundation and Australia-Korea Foundation. His book Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893-1948 (with Ae-Gyung Shim) is forthcoming in the Routledge Advances in Film Studies series.

They wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Peter Goderie and Brian Yecies, “Cultural Flows Beneath Death Note: Catching the Wave of Popular Japanese Culture in China,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 35-1-10, August 30, 2010.

Notes

1 While this figure from the 1980s seems rather large, the estimate is reproduced from the original source faithfully. More research on the peaks and troughs of annual ticket sales (and profits, which are currently on the rise) is needed elsewhere.

2 The small number of imported films screened in the PRC between 1949 and 1994 included Salt of the Earth (1954) and Rambo: First Blood (1982). The rights to show these films were not bought with a percentage of box office revenue, as per a standard box-office-split deal, but with a flat fee paid to the American distributors using the CFC’s meagre export earnings (Wang, 2007, p. 1; Berry and Farquhar, 2006, p. 205).

3 With the influx of even this relatively small number of foreign films, China’s own relatively low-budget production industry has struggled to remain competitive in the local market. Between the withdrawal of much state sponsorship and the impossibility of gaining permission to make the films they wanted, a number of directors who began their careers in the 1990s, the “Sixth Generation”, broke away from the mainstream studios and began producing low-budget films for overseas distribution. These films were often filmed on hand-held cameras and using a naturalistic “documentary” style, without permits (Zhang, 2004, p. 289). The directors include Lou Ye, Zhang Yuan, and Wang Xiaoshuai. Despite their recognition in the rest of the world, these filmmakers have been mostly banned within China. At the other end of the spectrum, a type of film, which became a clear staple of Chinese cinema by the late 1990s, the “new mainstream”, earned moderate success by mimicking the style of Hollywood films, though these films still did not typically reach a very wide audience (Lau, 2007, p. 1).

4 Note that these figures are for internationally successful blockbusters: in such a market, heavily censored lower-budget domestic films have even slimmer chances of commercial success.

5 The original Death Note serial manga (Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata) was published in Weekly Shonen Jump magazine from 2003 to 2006. The franchise was expanded by two live-action films in 2006 and a 37-episode animated television series in 2006-2007, as well as several video games and a third spin-off movie.

6 Fansubbing is defended by its practitioners on the grounds that it promotes an otherwise unattainable product to new audiences and thus creates demand (and therefore sales and profit for the copyright holder) which would not have existed without the original act of piracy (Riedemann, 2006; Jenkins, 2006). Nonetheless, Japanese copyright holders have insisted that fansubbing is still piracy, especially in healthy markets where a demand for anime already exists, and have taken legal action against its practitioners (Cintas and Sánchez, 2006, pp. 44-5). In principle, fansub producers encourage users to destroy their illegal copies as soon as a legal alternative becomes available in their country, but in practice many fans have little motivation to do so.

7 Japanese film and television are controversial in China to begin with simply by virtue of being Japanese. In 2000, nearly all cartoons shown on Chinese television were Japanese, and the SARFT began instituting regulations to limit the amount of screen time of Japanese cartoons and to promote domestic alternatives (China Daily 2008b). Yet a 2006 survey found that 80 per cent of Chinese children still preferred these foreign cartoons to locally produced ones (Coonan, 2006). Since 2006, all foreign cartoons have been banned from Chinese prime-time television; the ban was extended by an hour per night in February of 2008 (China Daily, 2008b). China’s role in outsourcing animators for overseas producers has allowed the government to push for a stronger domestic animation industry with less violence than in many popular anime and a “positive social message”, particularly of the continuing relevance of the CCP (Hewitt, 2007).

Similar controversies have existed over the popularity of South Korean television dramas in China. Of particular note are government efforts to crack down on historical dramas such as Taewang Sashingi (aka Legend, 2007), Daejoyeong (2006) and Yeongaesomun (2006), which challenge both the official Chinese version of history and the popularity of domestic production (Coonan, 2007b). As in the case of Death Note, piracy has been identified as a popular method of circumventing the censorship of these programs (Chien, 2006).

8 Death Note is not the only media to be banned in China for its incidental horror themes, nor was it the sole precipitator of the general ban on the horror genre in 2008. For example, the supernatural is a staple of the Hong Kong film industry, but supernatural themes are forbidden from CEPA co-productions, even when the films are based on Chinese ghost stories (Hammond, 2004). Among many other censored western products, the video game World Of Warcraft and the films in the Pirates Of The Caribbean series (2003, 2006, 2007) were heavily censored for their release in China by removing depictions of magically animated human skeletons (and Chow Yun Fat), although consumers of these products, too, have illegal ways of reintroducing the cut content (Slashdot, 2008; Coonan, 2007a; Guardian, 2006; BBC News, 2007).

9 Similarly mocked censorship decisions include the 2006 ban on live-action television programs with animated characters, in the style of Space Jam (1996) or Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), when SARFT demanded that channels devoted to animation “rid themselves of inappropriate live-action” (Landreth, 2006; Schwankert, 2006). Variety and Asia Times have claimed that Babe (1995) was banned in China on the basis that “animals can’t talk and some viewers would be confused” (Hammond, 2004; Schwankert, 2006).

10 Names appearing in single quotations are pseudonyms.

11 Subsequent investigation showed that Death Note products were still accessible via BitTorrent links on Chinese websites, but were noticeably absent from the extensive manga archives of dm.idler-et.com and the infamous video sharing site tudou.com (even though the latter was found to host Chinese-subtitled videos of contemporary US and Japanese television series) (BTChina, 2008; Idler, 2008; Tudou, 2008).

References

Anime News Network (2005) Death Note stirs controversy in China, accessed 14/8/08.

Anime News Network (2007) Virginian teen suspended over names in Death Note, accessed 20/9/08.

Anime News Network (2008a) South Carolina student removed over Death Note list.

Anime News Network (2008b) Alabama 6th grade boys arrested for Death Note book, accessed 20/9/08.

Anime News Network (2008c) Four Washington middle schoolers disciplined over Death Note, accessed 20/9/08.

BBC News (2007) China censors ‘cut’ Pirates film, accessed 27/9/08.

Berry, Chris and Farquhar, Mary (2006) China On Screen: Cinema and Nation (New York: Columbia University Press).

Business Weekly (2003) Hero: box office saviour, accessed 26/7/09.

Box Office Mojo (2008), accessed 6/9/08.

BTChina (2008), accessed 26/9/08.

Chao, Loretta (2008) China is likely top internet user, The Wall Street Journal, 14 march.

Chien, Eugenia (2006) China, Taiwan crack down on Korean soap operas, Pacific News Service, accessed 28/9/08.

China Daily (2007) ‘Death Note’ days numbered, accessed 14/6/08.

China Daily (2008a) China bans horror audio, visual products, Harry Potter excluded, accessed 4/6/08.

China Daily (2008b) China to extend ban on foreign cartoons, accessed 20/9/08.

China Information Agency News (2007) cited by Comi Press, Shueisha responds to China banning Death Note, accessed 15/7/08.

China Internet Network Information Centre (2002-2009) Statistical reports on the internet development in China, accessed 11/3/09.

Chu, Yingchi (2002) The consumption of cinema in contemporary China, in Stephanie Donald, Michael Keane and Yin Hong (eds) Media In China: Consumption, Content and Crisis, pp.43-54 (London: RoutledgeCurzon).

Chutian Metropolis Daily (2007) cited by Comi Press, Death Notes confiscated in Wuhan, China, accessed 15/7/08.

Cintas, Jorge and Sánchez, Pablo (2006) Fansubs: audiovisual translation in an amateur environment, The Journal Of Specialised Translation 6, pp.37-52.

Comi Press (2006) Death Note movie breaks Hong Kong box office records, accessed 15/7/08.

Comi Press (2007) Death Note in China – success or disaster?, accessed 15/8/08.

Coonan, Clifford (2006) China bans foreign cartoons from TV prime-time schedule, The Independent, August 15 (London).

Coonan, Clifford (2007a) China censors change Warcraft game, Variety Asia Online, accessed 27/1/09.

Coonan, Clifford (2008a) Chinese DVD pirate faces prison, Variety Asia Online, accessed 10/2/09.

Coonan, Clifford (2008b) Han invites foreign investment in China, Variety Asia Online, accessed 11/2/09.

Dowell, William (2006) The Internet, censorship, and China, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 7(2), pp.111-119.

Elley, Derek (2007) Review of Death Note: The Last Name, Variety, accessed 10/2/09.

Fleming, Michael (2009) Warner brings Death to big screen, accessed 10/4/10.

Guardian (2006) China sinks Dead Man’s Chest, accessed 27/7/08.

Hammond, Stefan (2004) China spooked by Hong Kong’s films, accessed 27/9/08.

Hartford, Kathleen (2000) Cyberspace with Chinese Characteristics, Current History 99(638), pp.255-262.

Hewitt, Duncan (2007) A state of fantasy; Chinese leaders once feared animation as a corrupt foreign influence. Now they see it as the next export industry, Newsweek International, July 30th (New York).

Hood, Marlowe (2005) Steal this software, IEEE Spectrum, June, pp.52-53.

Hu, Jubin (2003) Projecting a Nation: Chinese National Cinema Before 1949 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press).

Idler (2008), accessed 26/9/08.

Jenkins, Henry (2006) When piracy becomes promotion, Reason Magazine, accessed 27/5/09.

La Denière Heure (2007) Forest : le tueur aux mangas, accessed 15/6/08.

Landreth, Jonathan (2006) China bans TV toons that include live actors, Backstage, accessed 20/9/08.

Lau, Jenny (2006) Hero: China’s Response to Hollywood Globalization, Jump Cut 49.

Lin, Steven (2007) Pfhhh, you call that a copyright violation?, China Daily, accessed 20/9/09.

Madman (2009) Death Note (anime), acessed 20/1/10.

Massey, Joseph (2006) The Emperor is far away: China’s enforcement of intellectual property rights protection, 1986-2006, Chicago Journal of International Law 7(1), pp.231-237.

Mingxin, Bi (2008) China not to implement film rating for the moment, Xinhua, accessed 20/9/08.

Motion Picture Association International (2004) The Cost of Movie Piracy, accessed 18/8/09.

Motion Picture Association International (2008a) MPA partners China film organizations to launch 2nd nationwide anti-piracy contest, accessed 18/8/09.

Motion Picture Association International (2008b) MPA distributes file sharing education booklet and launches anti-piracy campaign, accessed 18/9/09.

Palmer, Augusta (2006) Mainland China: the new entertainment film in AT Ciecko, Contemporary Asian Cinema, pp.144-155 (New York: Berg).

Pang, Laikwan (2002) The global-national position of Hong King cinema in China, in Stephanie Donald, Michael Keane and Yin Hong (eds), Media In China: Consumption, Content and Crisis, pp.55-66 (London: RoutledgeCurzon).

Pang, Laikwan (2004) Piracy/privacy: the despair of cinema and collectivity in China, Boundary 2 31(3), p.101-124.

Paquet, Darcy (2008) ‘Chaser speeds to top of Korean B.O.,’ Variety, accessed 10/7/08.

People’s Daily Online (2007) China continues crackdown on Japanese Death Note horror stories, accessed 15/7/08.

Psiphon (2008), accessed 27/7/08.

Qiang, Xiao (2006) Image of Internet Police: Jingjing and Chacha online, China Digital Times, accessed 4/9/09.

Rawlinson, David & Lupton, Robert (2007) Cross-national attitudes and perceptions concerning software piracy: a comparative study of students from the United States and China, Journal of Education For Business, November/December 2007, pp.87-93.

Reuters (2007) Beijing bans scary stories to protect young, accessed 14/6/08.

Reuters (2008) Regulators now spooked by ghost stories, accessed 4/6/08.

Riedemann, Dominic (2006) What cost piracy?, Suite 101, accessed 15/6/08.

RMBGuide (2006) Average exchange rate of RMB yuan, accessed 26/9/09.

Screenville (2008) World Cinema Stats, accessed 11/2/09.

Slashdot (2008) China bans horror movies, accessed 4/6/08.

Smith, Ian (2008), International Film Guide 2008, pp.131-134 (London: Wallflower Press, London).

Spencer, Richard (2008) China’s censors to ban Steven Spielberg’s ET, Telegraph, accessed 4/6/08.

Star, The (2007) Last but not least, accessed 27/7/08.

State Office of Intellectual Property Protection of the PRC (2006) China’s action plan on IPR protection 2006, accessed 11/9/08.

Schwankert, Steven (2006) China applies toon taboos, Variety, accessed 20/9/08.

Sun, Yunlong (2008) China intensifies crackdown on horror audio and videos, China View, accessed 28/7/09.

Thompson, Anne (2008a), Subtitled films seek to break mold, Variety, accessed 16/9/08.

Thompson, Anne (2008b) Hollywood puts focus on China, Variety, accessed 16/9/08.

Time (1982) VCRs go on fast forward, accessed 20/9/09.

Tor: anonymity online (2008), accessed 27/7/08.

Tudou (2008), accessed 26/9/08.

UltraReach (2008) UltraSurf, accessed 25/7/08.

USC US-China institute (2008) Talking points, April 30-May 17, accessed 20/9/08.

Wade, Jared (2007) The debate on Chinese counterfeits hits the WTO, Risk Management, 54(6), p.10.

Wang, Ting (2007) Hollywood’s crusade in China prior to China’s WTO accession, Jump Cut 49.

WebSitePulse (2008) Website test behind the Great Firewall of China, accessed 21/9/08.

Yahoo! Japan (2007) cited by Comi Press, China Death Note Problem Appears on National TV, accessed 15/7/08.

Zhang, Yingjin (2004) Chinese National Cinema (New York, Routledge).

Zhou, Wenxin (2007) Death Note censors receive threats from students, accessed 27/7/08.