Washington’s Double Vision: al-Qaida, Iran and Global Islamo-fascism

Paul Rogers

First, the four coordinated truck-bombings of 14 August 2007 which targeted the Yezidi religious minority in northern Iraq inflicted the largest death-toll of any single incident – more than 400 – since the invasion of Iraq in March 2003. Second, the US’s indication that it intends to designate Iran’s 150,000-strong Sepah-e-Pasdaran-e-Enghlab-e-Islami (Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, or Pasdaran) as a “foreign terrorist organisation” entails more than an escalation of rhetoric: it has serious practical implications for the relationship between Washington and Tehran, and adds a further element to an already polarised atmosphere where the possibility of military action against Iran cannot be ruled out (see Helene Cooper, “U.S. Weighing Terrorist Label for Iran Guards”, New York Times, 14 August 2007).

Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps

Iraq’s storm

The devastating human cost of the assault on the Yezidis in Nineveh province has rightly been the main focus of attention in its immediate aftermath. On a political level, its motivation may not be so straightforward as pure sectarian hostility towards a supposedly heretical sect. Rather, it almost certainly forms part of a wider political agenda to limit Kurdish control of some of the key oilfields of northern Iraq. The Mosul district in particular is central to this objective (see Patrick Cockburn, “Desperate search for survivors among Yazidi homes destroyed by bombers”, Independent, 16 August 2007)

Search for survivors following the Ninevah truck bombing

This presents a problem for US forces, whose intensive concentration on the “surge” strategy in Baghdad and other selected areas means that are no longer present in large numbers in Mosul; this makes it easier for formerly Baghdad-based insurgents to regroup and operate elsewhere. But if the vulnerability of communities such as the Yezidi to insurgent attack in such circumstances is thereby exposed, it would be wrong to conclude by default that the surge in Baghdad itself is working.

The reality is that even in the greater Baghdad area the insurgency continues. The day of the Yezidi attacks, 14 August, was marked by lesser-reported incidents in the capital or its vicinity: the destruction of a major bridge on the Baghdad-Mosul road, the loss of a US helicopter (with five service personnel killed), and – an extraordinary incident – the kidnap of several oil-ministry staff (including a deputy minister) by around fifty uniformed gunmen in seventeen ostensibly official vehicles.

How does the George W Bush administration respond to this pattern of events? Both it and American military leaders have been quick to blame the al-Qaida movement (in the form of its putative Iraqi affiliate) for the Yezidi attacks at least; and the president and his chief allies maintain an unbending view of the Iraq insurgency in general as an almost entirely al-Qaida operation.

Washington’s narrative of the core role of al-Qaida in Iraq may retain considerable have domestic value in its ideological presentation of the Iraq war as part of the wider response to 9/11. The problem is that it then comes into tension with the fact that the main current challenge to United States forces in Iraq comes from Shi‘a militias, whom Washington sees as sponsored or supported by Tehran. Indeed, some US military sources see the militias as presenting the most severe long-term threat (see “Iraq’s high summer”, 9 August 2007); for example, General Raymond Odierno has said that in July 2007, no less than 73% of all attacks in Iraq were launched by Shi’a militias rather than the al-Qaida movement or Sunni nationalist insurgents.

Indeed, a big part of the military surge has actually been the attempt to curb the power of these militias (see Gareth Porter, “US ‘surges’, soldiers die, Blame Iran”, Asia Times, 16 August 2007). The Bush administration’s determination to highlight the al-Qaida connection partly explains why this aspect of US strategy has not been widely reported. At the same time, the need to sustain the momentum of antagonism towards Iran means that the Shi‘a militias are a useful card to deploy in a verbal barrage that is notably increasing.

Iran’s windfall

There’s no escaping Iran. What is particularly problematic for Washington is an unforeseen geopolitical effect of its war in Iraq: that Iran, the most significant remaining member of the original “axis of evil” has seen regimes to its east and west (the Taliban’s Afghanistan and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq) terminated – yet Tehran has been able but to relate more closely with the successor regimes in both states, even though these are supposedly pro-American.

This readiness to make friends with the United States’s allies in no way modifies the Bush administration’s view that Iran remains its main state enemy, one moreover that is tainted by endorsement of and participation in “terrorist” activity.

This is a viewpoint that has been expressed at official level on many occasions before the “naming” of the Revolutionary Guards; to take but one example, a press release of 5 September 2006 entitled “In Their Own Words: What the Terrorists Believe, What They Hope to Accomplish, and How They Intend to Accomplish It” cites the main al-Qaida leaders, but (as Nick Ritchie has pointed out) also refers four times to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad under a sub-heading that reads, “The Terrorists On Their Absolute Hostility Towards America”.

In this light, the signalled branding of the entire Revolutionary Guard as a foreign terrorist organisation is both a continuation and an extension of existing charges against Tehran and its leading state organisations, in particular that the guards have directly aided insurgents in Iraq through the provision of training and weapons.

Again, the move may not be all it seems. The US decision may in part be motivated by an effort to “bounce” both the US’s allies and the United Nations Security Council into agreeing tougher sanctions against Iran. Moreover, it comes at a time of real concern in Washington at the manner in which Iran is seeking to capitalise on its geopolitical windfall by soliciting its neighbours.

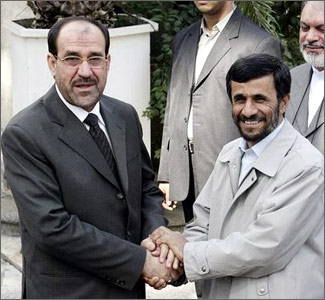

The three-day visit to Tehran by Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki in August 2007 (his second in a year) is awkward for the US government; not least, it contributes to the political chaos in Baghdad by alienating further the leading Sunni political representatives who have resigned from the government (a situation which the Shi’a-Kurdish deal announced by Iraq’s president, Jalal Talabani, on 16 August is unlikely to reverse).

Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki (left) greeted by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad on his first visit to Tehran

On the other side of its border, President Hamid Karzai has – even before the visit to Kabul of his Iranian counterpart Mahmoud Ahmadinejad on 14 August – spoken favourably of the cooperation between the two countries, of Iran’s substantial reconstruction aid which benefited Afghanistan’s western provinces, and of Iran’s (albeit increasingly reluctant) hosting of huge numbers of long-term refugees from Afghanistan’s wars.

Putting reality together

How does the Bush administration manage to make an intellectually coherent case for a need to keep both al-Qaida and Iran in its sights? Some of the more radical elements of the neo-conservative fringe in Washington ingeniously make the case the Tehran regime and al-Qaida are two sides of the same threat; but this is hard to argue for at a level deeper than ideological convenience.

In such circumstances, the most reliable standby is the mechanistic, Manichean view of the “war on terror” as propagated by some of the unreconstructed but still influential elements around the White House (see “The world as a battlefield”, 9 February 2006).

After 9/11, the war was directed very largely against the Taliban hosts of the al-Qaida movement in Afghanistan, notwithstanding some early efforts byconservative opinion-formers to include Iraq. But in the first half of 2002, two key speeches by George W Bush expanded the entire remit of this war.

First, his state-of-the-union address on 29 January 2002 identified North Korea, Iran and Iraq as the much-vaunted “axis of evil”, arguing that their pursuit of weapons of mass destruction and support for terrorism made these regimes unacceptable in a civilised world. Second, his speech at the West Point military academy on 1 June 2002 emphasised America’s right to pre-empt future threats.

In the five and a half years since – a period of spreading conflict in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon, and persistent al-Qaida attacks – the “war on terror” has metamorphosed into an even wider “long war against Islamofascism”. This embraces a host of suspects: al-Qaida itself; the Taliban; Islamist militias in Pakistan, Somalia, north Africa, Thailand and the Philippines; all the differing insurgent groups in Iraq; Hamas in Palestine; Hizbollah in Lebanon; and now the Revolutionary Guard in Iran.

This crude and simple worldview bears little relation to reality. What is more important, however, is its political potency. The George W Bush administration may be trapped by a fantasy of power and control that is ever farther out of reach; but as the presidential and congressional elections of 2008 approaches, it is likely to use the enormous resources at its disposal to project this fantasy to the American people with undiminished vigour.

Paul Rogers is professor of peace studies at Bradford University, northern England. He has been writing a weekly column on global security on Open Democracy since 26 September 2001. This article appeared at Open Democracy on August 16, 2007. His latest book is Global Security and the War on Terror: Elite Power and the Illusion of Control. Published at Japan Focus on August 17, 2007.