Paul Rogers

Three concerns – oil, China and the war on terror – are pushing the United States toward greater involvement in Africa.

The new United States defence budget involves a substantial increase in spending and a redirection of many military programmes towards counterinsurgency and responding to asymmetric warfare (see “The costs of America’s long war”, 8 March 2007). It also entails a relatively little-noticed change in the orientation of the US military towards Africa, announced on 9 February 2007: the planned establishment of Africa Command (Africom).

At first sight this may appear a surprising move, given the comparatively less prominent place of Africa in the global war on terror compared with the middle east or south Asia. One way to explain the policy decision is to put it in the context of the establishment of another US military command almost a generation ago.

The pre-history of Africom

In October 1973, action by Arab oil producers during the Yom Kippur/Ramadan war resulted in a massive and unexpected increase in oil prices. Prices almost doubled within a few days, and in the following months more than doubled again. By May 1974, a barrel of oil cost around 450% higher than eight months previously; the entire process inaugurated a period of economic stagnation and inflation in western states, and huge problems for the economies of developing-world countries.

These “third-world” states, urgently needing to survive the sudden downturn, borrowed heavily on international financial markets flush with petrodollars – a process that set the scene for the debt crises of the 1980s and 1990s. Military planners in the west, meanwhile, drew a salutary lesson from the oil crunch: western economies were far more dependent on middle-east oil than their elites had appreciated.

This worrying situation arose in the context of cold-war rivalries between Nato and the Warsaw Pact, characterised by fears that a Soviet Union self-sufficient in oil supplies might (in some future crisis) seek to interfere with western oil imports from the Persian Gulf. The Pentagon in the mid-1970s was awash with urgent scenario-planning documents assessing whether the United States and its allies had the capacity to intervene in the oil-rich states of the Gulf, in the event of a violent interruption of deliveries. These analyses tended to throw up an uncomfortable conclusion: that despite the impressive global-reach capabilities of the United States navy and marine corps, neither the US nor its allies had any serious capacity to move forces rapidly into the region.

By 1977 this had become a crucial if unpublicised issue for US strategists, and the then president Jimmy Carter issued a presidential directive ordering plans for some kind of integrated military force that could be available at very short notice. Its creation had to overcome delay caused by inter-service rivalry, and it was only at the end of the decade that the Joint Rapid Deployment Task Force (more commonly known as the Rapid Deployment Force / RDF) was established.

By the early 1980s – with Ronald Reagan in the White House, the cold war at its height, and after the shock of the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis – the RDF was being organised into an entire unified military node: Central Command, or Centcom. It initially covered an arc of nineteen countries from Kenya through the Gulf region to Pakistan, and could call on hundreds of thousands of troops and marines, hundreds of planes and scores of warships (today the number of countries included in its remit is twenty-seven).

Centcom was a fully integrated command, along the lines of other overseas US military organisations such as Southern Command (which covers Latin America) and Pacific Command. Centcom was at the core of the war against Iraq in 1991, with its commander, General Norman Schwarzkopf, in overall charge of the military operation; more recently it has run the war in Afghanistan and the second Iraq war. Its origins, however, are rooted in the experience of the mid-1970s and relate particularly to oil security (see “Oil and the “war on terror”: why is the United States in the Gulf?” 9 January 2002).

A triple threat

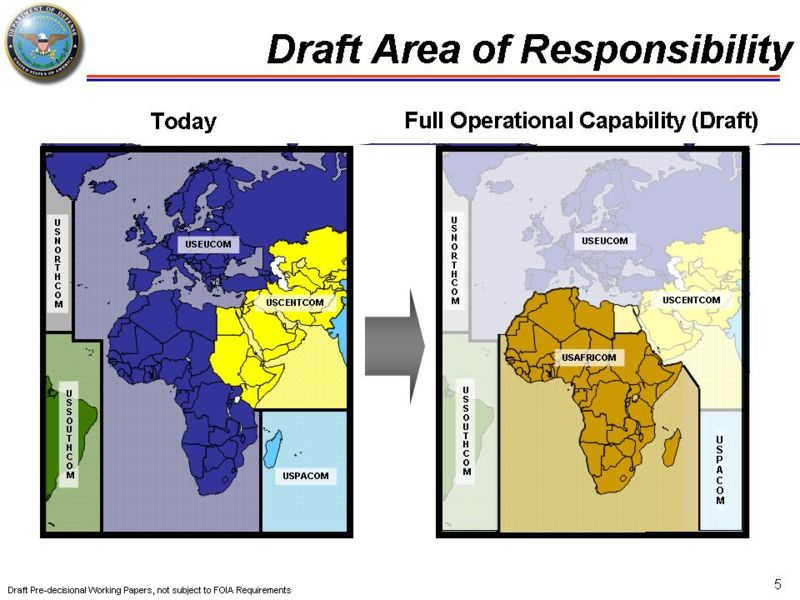

This is the context in which the United States is planning to establish a new unified military centre, this time covering the continent of Africa – which is currently “shared” between Centcom and the Pacific and European commands (Pacom and Eucom). When it becomes operational in September 2008 it will initially occupy headquarters alongside Eucom in Germany. Africom will share with Centcom a primary concern with resource security, but it will also keep a careful watch on two other current perceived threats: international terrorism and the rise of China.

The old and new US command structure: Africom

Indeed, all three factors – resources (especially oil), the war on terror, and China’s role in Africa – have already resulted in a steady increase in US military involvement in Africa (see Jim Lobe, “Africa to get its own U.S. Military Command”, Inter Press Service, 1 February 2007). The US military has made major counterterrorism training commitments in a range of countries across north Africa and the southern Sahara, and is developing closer ties with oil-rich states such as Nigeria.

US forces in Chad use GI Joe toys to demonstrate counter-terrorist tactics in July 2005

In the Horn of Africa, Centcom now has a substantial permanent base at Camp Lemonier in Djibouti, with around 1,800 troops based there for operations in the Horn and east Africa more broadly. In the extensive campaign against the Islamic Courts Union movement in Somalia in December 2006-January 2007, US units worked closely with the Ethiopian and Kenyan governments to remove the courts from the capital, Mogadishu, and conduct attacks on the movement’s alleged al-Qaida associates. These involved air operations conducted from a base in Ethiopia, and special-force units moving into Somalia from across the Kenyan and Ethiopian borders.

US Marines in action in Djibouti, Feb 2006

Most of the US operations in north Africa, the Sahara and the Horn are directed against presumed paramilitary groups, but the longer-term issue remains oil, especially in relation to China. Moreover, this focus is arising at a time when China, too, has its concerns over oil supplies. As recently as 1993, China was still able to produce all the oil it needed from its own reserves, but the change in recent years has been dramatic. Declining domestic oil production coupled with rapid economic growth and increased energy needs has meant that in 2006, China had to import 47% of all the oil it used, an increased import dependence of over 4% on 2005. At current rates, China will need to find close to two-thirds of all its oil from overseas by 2015.

The Chinese, like some Americans, are increasingly worried – several huge and long-term oil deals with Iran notwithstanding – at their heavy reliance on Persian Gulf oil. They have moved to develop better links with other producers, most notably Venezuela, but one of their greatest commitments is to African producers. In 2006, nearly a third of all Chinese oil imports came from Africa. Beijing has forged a particularly strong relationship with Sudan, and this has become a major factor in China’s reluctance to endorse any collective, international response to the Darfur crisis.

China’s interests in Africa are by no means limited to oil. China already has access to many international markets for a range of industrial and consumer products, but its rapid industrial growth makes it very keen to develop and expand into new ones. It currently sees African countries both as sources of raw materials (oil among them) and as potential markets for its own products. The growing interconnection between the two regions is reflected too in major political gatherings and visits, such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Beijing in November 2006, and the eight-country tour of Africa by Hu Jintao in January-February 2007.

All this raises the prospect of more intensive economic and political competition between the United States and China, rather than the risk of open conflict. The establishment of Centcom, however, raises the expectation of a shift in the nature of the US’s bonds with a number of African countries – towards a situation where policy towards Africa is mediated through military relationships fostered by the Pentagon, with all its financial resources rather than through the much more constrained state department and its operation of (for example) USAid development programmes.

The accumulated result is likely to be that the US approach to Africa will increasingly be determined by considerations of US military and political security rather than the human-security needs of relatively poor countries. At best that could see a curtailing of some valuable programmes; at worst it could mean a progressive militarising of relationships between Africa and the global north.

This article was published at Open Democracy March 16, 2007. It is published at Japan Focus on March 21, 2007.

Paul Rogers is professor of peace studies at Bradford University, northern England.