International Students and U.S. Global Power in the Long 20th Century

Paul A. Kramer

It was 1951 and Rozella Switzer, post-mistress of McPherson, Kansas, a prosperous, conservative, nearly all-white oil town of 9,000 people on the Eastern edge of the wheat belt, had not seen the Nigerians coming. That Fall, seven African students, all male, in their early- and mid-20’s, had arrived in the area to attend McPherson College and Central College. The accomplished young men, who counted among themselves a one-time math teacher, a surveyor, an accountant, a pharmacist and a railway telegrapher, had come with high professional aspirations to acquire training in agriculture, engineering and medicine; within months, they were treated to a fairly typical round of Jim Crow hospitality, from half-wages at the local laundry to the segregated upper-balcony of the local movie house. While at least one of the men had been warned by his father that Christians “’don’t practice what they preach’,” the students were apparently unprepared for the Midwest’s less metaphorical chill; with the arrival of winter, officials at McPherson College telephoned around town to gather warm clothes for the men, which is how they came to Switzer’s restless and expansive attention. A widow in her 40’s Switzer, according to Time, “smokes Pall Malls, drinks an occasional bourbon & coke, likes politics and people.” She was also “curious about the African students” and invited them to her home for coffee, music and talk.1

“What they said,” reported Time, “was an earful.” Isaac Grille, a 21-year-old surveyor and civil engineering student, passionately described a Nigeria surging towards revolution and independence, causes to which the men hoped to lend their training. The students ably played to anti-Communist fears with compelling accounts of perilous non-alignment, telling of “Nigerian friends who study in Communist countries, come back home ‘with plenty of money for political activity, and hot with praise for the Communists.” They apparently read Switzer an editorial (conveniently on-hand) from the West African Pilot by their “hero” Nnamdi Azikiwe who, while a “non-Communist… hates the U. S. for its segregation” and “writes that Communism is the form of government most likely ‘to ensure equality of freedom to all peoples.’” All of this got Switzer’s attention. Discrimination, she later recounted, had always made her “’mad,’” but this was different. “’This,’” she said, “’made me scared. All they knew about America was what they knew about McPherson. For the first time I really saw how important little things, a long way off, can be. We had to fight a one-town skirmish away out here in the middle of the United States.’”2

I’ll set to the side for a moment what Switzer decided to do about her guests’ perilous non-alignment and McPherson’s miniature Cold War dilemma, and instead translate the post-mistress’ anxious political observation (that traveling students had something to do with U. S. global power and its limits) into my own, historiographic one: that the history of foreign student migration ought to be explored as U. S. international history, that is, as related to the question of U. S. power in its transnational and global extensions.3 In this sense, my argument here is topical: that historians of U. S. foreign relations might profitably study international students and, in the process, bring to the fore intersections between “student exchange” and geopolitics.

The payoffs would be wide-ranging. Such scholarship would enrich our knowledge of the junctures between U. S. colleges and universities and American imperial power in the 20th century.4 To the extent that international students participated in the diffusion and adaptation of social, economic, and technical models they encountered in the United States, such studies would contribute to the historiography of “modernization,” “Americanization” and “development.”5 As witnesses, victims and sometimes challengers of racial exclusion in the United States, foreign students were important if still neglected protagonists in the politics of “Cold War civil rights.”6 Such research might explore the historical and institutional specificities of student migration within the broader panorama of “cultural diplomacy” efforts.7 Eventually, such histories might make possible large-scale comparative work on the geopolitical dynamics of student migration across educational metropoles.8

Work of this kind would build on rich, existing histories, which can be usefully gathered into three loose categories. First are histories of U. S.-based educational and governmental institutions at the organizational center of international student migration, among which Liping Bu’s deeply-researched monograph Making the World Like Us, from which I draw heavily in the present essay, stands out.9 There is scholarship that centers on specific educational programs such as the Boxer Indemnity Remission, the Philippine-American pensionado program, or the Fulbright Program.10 Finally, there is scholarship that treats the American encounters and experiences of foreign students, often organized by nationality or region of origin.11 While it thus has a strong foundation on which to build, an international history of student migration that places questions of U. S. global power at its center still remains to be written.

To date, one of the chief obstacles in attempting to intertwine histories of student migration and U. S. foreign relations has been historians’ reliance on the analytic categories and frameworks of program architects themselves. Many of the earliest accounts of these programs were produced in-house by practitioners (foreign student advisors and program officers, especially) which combined historical sketches with normative, technocratic assessments of program “effectiveness.”12 Thus, foreign students have often found a place in histories of “cultural diplomacy” alongside radio, television, artistic and musical propaganda, and approach which inadvertently reproduces a (somewhat sinister) aspiration from the period that “ideas” might be projected successfully by “wrapping them in people.”13 Most seductive, perhaps, is the category of “exchange” itself. Exchange—as in “educational exchange” or “cultural exchange”—is, after all, the peg around which both international student programs and of much of the scholarly literature that attempts to make sense of them quietly pivots. As a generality and organizing concept, it does successfully convey the fact of a multidirectional traffic, that is, foreign students entering the United States and U. S. students going abroad. But it fails cartographically: student migrations to and from the United States were scarcely “exchanges” in the pedestrian sense that most foreign students came from countries to which U. S. students by and large did not go; Europe proved a key exception in this regard. U. S.-centered student migrations resolve themselves into “exchanges,” in other words, only if one either generalizes from a European-American axis or flattens the rest of world into a unitary, non-American space.

“Exchange” also telegraphs a sense of equality, mutuality and gift-giving. But if the programs by and large did not involve geographic exchanges, neither were they exchanges in their cultural economics, either. While, for example, the organizers of “educational exchange” often hoped for visiting students’ conversion or transformation through their encounters with American culture and institutions, one searches in vain for affirmative descriptions of the radical changes that visiting students would introduce to American society in return. Where “exchanges” between Americans and foreign students were sketched, they were deeply asymmetrical. At most, Americans were to gain from these encounters a less “provincial” approach to the world; foreign students were, by contrast, expected to take away core lessons about the way their own societies’ politics, economics and culture should be organized. Clifford Ketzel’s insight, in a 1955 dissertation on the State Department’s “foreign leader” program, can easily be applied to cultural and educational “exchanges” more generally:

With the exception of many professor and teacher exchanges, the other programs are predominantly ‘one-way streets,’ i. e., they primarily encourage the export of American technical knowledge and the development of better understanding and more friendly attitudes toward the United States. Only secondarily, if at all, are they concerned with the understanding of other nations or the import of technical skills and cultural values from which the United States, as a nation, might profit.14

Stripping away the ideological idiom of “exchange” and examining how these projects were actually structured, one finds instead a set of three interlocking principles in play which proved remarkably resilient across time, across lines of sectarian and secular politics and across private and state sponsorship. The principle of selection involved the choosing of “representatives” from among what was believed to be another society’s future “directing” or “leading” class of political, cultural and intellectual elites, a process commonly understood not as selection but as “identification,” that is, the politically-neutral recognition of worth and leadership capacity on the basis of universally agreed-upon criteria. The principle of diffusion involved the assumption that foreign students would return home and, both consciously or not, spread U. S. practices and institutions, values and goods. To the extent that this diffusion was anticipated to travel not only outward from the United States but downward across the social scale of students’ home societies, it presumed and encouraged a vertical, top-down and authoritarian model of society. Third, the principle of legitimation involved the expectation that foreign students would, through their accounts of American life, play a favorable and vital role in aligning public opinion in their home societies towards the United States.

Across the long 20th century, of course, these same objectives also drove thousands of Americans the other way, across U. S. national borders, as students, teachers, missionaries, officials, professionals, experts and technicians.15 While not the subject of the present account, their story is nonetheless intimately bound up with it: these mobile Americans were often decisive in constructing, shaping and maintaining the long-distance fields of interaction that would draw foreign students to U. S. colleges and universities: “identifying” potential student-leaders abroad; training them in the language skills required for study in the United States; familiarizing them with (often idealized) accounts of American society and education; recruiting them for admission to U. S. educational institutions; and ultimately, helping to evaluate their “success” (however it was defined) as agents of diffusion and legitimation upon their return home. It was this dynamic of selection and recruitment—at the intersection between “outward” and “inward” migrations—that tended to give educational networks a tight-knit and even personalist character, a globalism of connected localities.

If my argument here is topical, it is also emphasizes two interpretations of international student migration to the United States in the long 20th century. First is an argument for continuity: that despite a mid-century takeoff in student migration coterminous with (if not determined by) rising government sponsorship, supervision and institutionalization, key linkages—especially at the level of personnel, practices and discourses—bound earlier to later 20th century educational programs. This was because, as existing research has shown, large-scale efforts by the U. S. state to cultivate student migration worked through—even as they transformed—pre-existing, private-sector infrastructure.16 In this respect, the role played by the U. S. government in the development of international student migration represents a variant of what Michael Hogan has called a corporatist configuration of state and private agencies in the United States’ relations with the global environment.17

Second, I argue that, across the long 20th century and down to the present day, international students in the United States have been imagined by American educators, government officials, journalists and many ordinary citizens as potential instruments of U. S. national power, eventually on a global scale. The question of how best to cultivate, direct and delimit their movements to and from the United States, how best to craft their experiences while in residence, and how to measure their impact upon the societies to which they returned, appeared early in the 20th century as high-stakes international and foreign policy concerns. Thus while Rozella Switzer’s “one-town skirmish” carried this sensibility both further “inward” (to a Kansas living room) and “outward” (to a global crisis) than was common before World War II, what might be called a geopolitical vision of international student migration was otherwise more exemplary than exceptional. Whether sponsored and administered by missionaries, philanthropists or government agencies, migrating students figured as prospective agents of U. S. influence in the world to which they would eventually return; American educational institutions came to be understood, both descriptively and prescriptively, as nodes and relays in global, U. S.-centered networks of power.18

If there is a case to be made for an international history of student migration to the United States, it might begin with striking correlations and counterpoints that bridge the two, usually separated spheres of foreign relations and educational history. Without U. S. colonialism, for example, it is extremely difficult to explain why Filipinos constituted one of the largest groups of Asian students, and of international students in the U. S. more generally, in the pre-1940 period. Latin American student flows, a relatively thin slice of the foreign student population prior to the mid-1930s, widened briefly to one of its thickest, precisely during a period of deepening U. S. government concern over hemispheric solidarity against encroaching fascism. Postwar, state-sponsored programs in reeducation and “democratization” helped pushed Japan from twenty-second to tenth among student-sending countries and Germany from seventh to third. By contrast, the Soviet Union saw its student numbers in the United States decline during the Depression and collapse with the onset of the Cold War, dwindling to a lonely two by 1956. All this suggests a rough, imperfect elective affinity, in other words, between educational networks and the geopolitics of “friendship” and “enmity.”

This said, the world politics of student migration was always multi-layered: the imprint of U. S. state power in shaping these movements, for example, was uneven, felt more forcefully in some settings and moments than in others. Other factors, many of them far from conventional foreign policy concerns, played equally central roles in making and unmaking these transits: the presence or absence of pre-existing networks that either mitigated or exacerbated the friction of travel and logistics; economic stability and prosperity sufficient to generate necessary sponsorship locally; the availability and desirability of modern higher education closer to home, and the attractiveness of other nations’ educational and political systems, for example. When it came to educational circuits, in other words, diplomacy was not destiny.

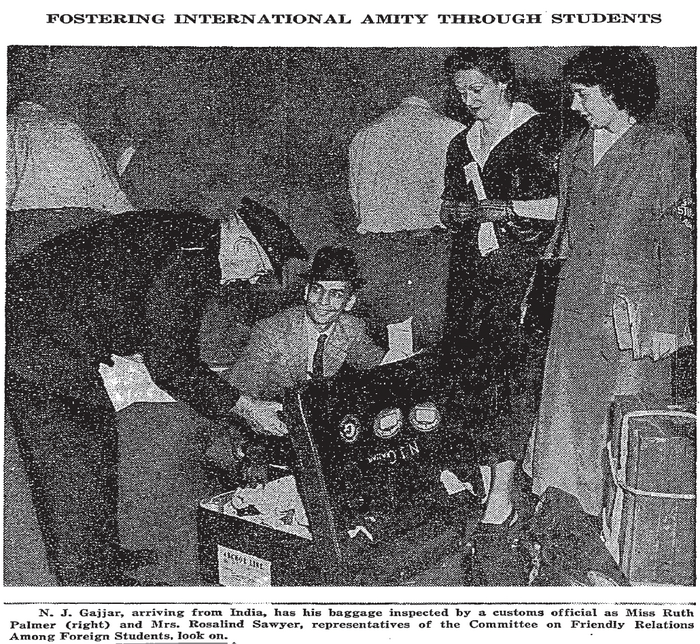

Pier and airport greeting services like this one, organized by private organizations like the YMCA’s Committee for Friendly Relations with Foreign Students, were intended to mitigate arrival shocks and establish positive first-impressions that would both buffer visiting students from mistreatment and orient their loyalties to the United States. The two standing volunteers wear blue armbands labeled “Foreign Student Adviser.” From “Foreign Students Get Welcome Here,” New York Times, August 27, 1949, p. 15.

And things did not always (or even frequently) turn out as planned. Innumerable obstacles interrupted or deflected projected circuits of personnel, ideas and allegiances. Selection, diffusion and legitimation, while devoutly hoped for, sometimes spilled off the rails, when screenings failed to prune student radicals and dissenters, when students’ lateral solidarities overtook hoped-for vertical loyalties, when students’ encounters with the U. S. state and civil society proved alienating rather than binding. Then there were those more dramatic failures of educational power. There was what might be called the Yamamoto problem, when a former student in one’s military academy ended up using this training against one’s own country in war. There was the Nkrumah problem, when foreign students developed into radical, anti-colonial nationalists.19 There was the Qutb problem, when a visiting educator discovered in one’s society a religio-political enemy with whom no exchange could be suffered.20

One way to begin resolving into meaningful histories the nearly infinite tangle of international student trajectories is to identify distinct and recognizable projects that animated and organized them, and to establish some loose chronological benchmarks. The first of three periods I’ll identify here, stretching from the late-19th century to around 1940, was characterized by four, parallel and overlapping types of student movement that can be distinguished by their objectives, definitions of education and its utility, and structures of authority and sponsorship: migrations aimed at self-strengthening, colonialism, evangelism, and corporate internationalism. They are presented self-consciously here as a register of something like ideal types, subject to subdivision, in which historical instances always crossed and blended. A second moment, dating from the years leading up to World War II to the late-1960s, saw the exponential growth and diversification of international student migration to the United States, greater participation of U. S. government institutions in promoting and shaping it, and its intensifying geopoliticization, both structurally and discursively. Most of all, this period was set apart by a widespread, sharpened sense of foreign students as critical actors in the global politics of the Cold War and decolonization. A third moment, sketched only briefly here by way of conclusion, stretches from the 1970s to the early 21st century, and is characterized by the further increase of student migration to the United States at the nexus of privatizing universities and globalizing corporations. Here, as in the early moments, border-crossing students would be freighted with both aspirations for U. S. global power, and apprehensions about its limits.

The first of my pre-1940 types comprised outward, “self-strengthening” movements by students propelled by a sense of domestic social crisis, the exhaustion or failure of traditional solutions, and the perceived success of other, commensurable societies facing similar dilemmas. The paradigmatic sending society under this heading, in many ways, was the United States: facing industrial capitalist conflict and social upheaval in the late-19th century, hundreds of American students traveled to German universities in search of answers, returning home with new, state-centered models of social reform and blueprints for the research university itself; they would face many obstacles in their efforts to transplant what they had learned in the U. S. institutional and ideological context, but would remake the landscape of U. S. politics, social thought and education in the process.21 While these transits bridged powerful, industrialized regions, other self-strengthening migrations were produced by crises of imperial subordination, when weakening states attempted to fight off greater surrenders of sovereignty by sending their youth abroad to selectively import the tools of their would-be colonizers, as a bulwark against complete external domination.22 The abortive Chinese Educational Mission of the 1870s and early 1880s, which sent 120 young men to high schools in New England and some to colleges and universities, was exemplary in its hopes to prevent further greater decline through the selective borrowing of Western science and technology, a process that reformers called “learning from the barbarians in order to control the barbarians.” The program, initially intended to last fifteen years and to include college education, collapsed after only eight, as the students themselves chafed under the demands of both U. S. and Confucian educations, and as conservatives in China increasingly suspected the students of barbarism and disloyalty. Many of the Mission’s participants nonetheless went on to occupy places of prominence in engineering, military technology and education during the last years of Qing rule.23

As Chinese efforts suggested, some of the most sought-over settings for the pursuit of literal self-strengthening were U. S. military academies. Attendance at the academies by international students began following Congressional authorization in July 1868.24 Caribbean and Central and South American states successfully presented candidates: by 1913, at least two Costa Ricans had studied at the U. S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and West Point had admitted students from Cuba, Honduras and Ecuador.25 “Many foreigners have been educated at West Point,” noted the New York Times that year, “and to-day West Pointers are officers in nearly every regular military establishment in Central America.”26 U. S. military training was also actively pursued by East Asian states attempting to fend off Western colonization. Qing attempts to achieve their first West Point appointments had stalled in the 1870s, and the Chinese would have to wait until 1905.27 By contrast, Japan (which appears to have pressed for the first international admissions in 1868) could by 1904 boast seven graduates from Annapolis, including the commander of the Japanese Squadron of the Far East; in 1913, another graduate, Count Yamamoto, became premier of Japan.28

A second category, in many ways the inverse of the first, consisted of colonial and neo-colonial migrations. These were educational circuits organized by imperial states with the aim of crafting a loyal and pliable elite in the hinterlands with ties to metropolitan society and structures of authority. An early and private variant in the British context was the Rhodes Scholarships, which had as their goal the integration through educational migration of a British-imperial, Anglo-Saxon race whose domain included the United States.29 U. S.-centered variants of such migrations were inaugurated after 1898, most ambitiously but not exclusively in the United States’ new empire in Asia.30 Some of these circuits wound through U. S. military academies. Filipino admission to the academies was anticipated even before the end of the Philippine-American War, but it was only in March 1908 that Congress authorized the admission of seven Filipinos to West Point, for future commission to the Philippine Scouts.31 The 1916 Jones Act permitted up to four Filipino midshipmen to be enrolled at the Naval Academy at one time; the first Filipinos arrived in 1919, and by 1959, twenty-four had graduated and returned to serve in the Philippine navy.32

More ambitious in scope was the consolidating Philippine-American regime’s civilian pensionado program, established in 1903, which would eventually sponsor the travel and education of hundreds of elite Filipinos from across the archipelago to colleges throughout the United States, with the requirement of service in the U. S. colonial bureaucracy. By 1904, program supervisor William Sutherland would write optimistically if vaguely from the United States to the Philippines’ Governor General of “the advisability of this investment in ‘Americanization,’… not to mention the extremely favorable political and moral effect that this philanthropic work of the government produces both here and in the Archipelago.” While the program’s objective was the “assimilation” of the pensionados and their diffusion of U. S. loyalties, values and practices, students traced a variety of paths from colonial attachment to nationalist estrangement; upon their return, many played critical roles in government, education and business, helping make possible the “Filipinization” of the colonial regime that accelerated in the 1910s and culminated in the Philippine Commonwealth of the 1930s.33 A still larger project, in a neo-colonial vein, began in 1909 with the U. S. government’s remission of a Chinese overpayment of the Boxer Indemnity, returned with the stipulation that the funds be used exclusively to fund educational travel to the United States, with initial training at the jointly run Qinghua Preparatory School. Similar in goals to the pensionado program, the School and larger Remission quickly brought neo-colonial and self-strengthening agendas into collision, as U. S. diplomats pressured Chinese officials and educators over administrative power, curricula, and the appointments of students, faculty and staff and as Chinese educators sought to adapt the school to a self-consciously nationalist era.34

A third category consists of what can be called evangelical migrations. These were mediated by the United States’ expanding Protestant missions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which connected promising students and converts from far-flung mission schools to denominational colleges throughout the United States.35 The goal here was to funnel talented “native” would-be missionaries to centers of theological intensity and fervor in the United States and then to cycle them back to their home societies to spread both the Gospel and Americanism.36 “It is of the utmost importance, both for their nations and for ours,” wrote W. Reginald Wheeler, co-editor of a 1925 YMCA survey of “The Foreign Student in America,” “that they return to their homes with an adequate comprehension and appraisal of the life and spirit of America” and, especially, Christianity’s place in “building up the institutions and the life of our republic.”37 While the largest numbers of student converts in the late-19th and early 20th centuries were recruited from Asia, it was also during this period that the first African students were recruited to black colleges and universities in the United States by African-American missionaries.38 The attraction of such U. S.-educated native missionaries to Protestant denominations would only increase after World War I, as Western missionaries came to be seen in many mission fields as an intrusive, “imperialist” presence. Their appeal to potential converts grew with the missions’ turn in the early 20thcentury toward Social Gospel projects for the delivery of medicine, social services and education, which allowed international students to locate themselves educationally and professionally at the intersection of missionary and self-strengthening efforts. But even where they did not organize or sponsor student circuits themselves, Protestant missionaries actively attempted to evangelize foreign students studying in the United States toward non-religious ends. Beginning in 1911, for example, the international branch of the YMCA organized the Committee for Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students, an organization whose conversionist goals were packaged inside a broad array of support services, from greeting at ports of entry, to mediation with immigration authorities, to organized Sunday suppers.39 Protestant groups from China, Japan, Korea and the Philippines would develop as among the most well-organized foreign student associations of the early 20th century.40

Foreign students and visitors, and their instructor, a specialist in the teaching of English as a foreign language, in an English class at the American University Language Center in Washington, DC. Such settings, while helping visitors to acquire necessary cultural skills, placed many who were not technically students in the structural position of “students.” From the University of Arkansas Special Collections, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Collection. My thanks to Vera Ekechukwu for locating this image.

A fourth and final category of pre-1940 student migrations can be described as corporate-internationalist. These developed in the aftermath of World War I among educators and business and philanthropic elites preoccupied with the causes of the war, and possible ways to forestall future conflict. They derived what can be called the proximity theory of peace: ignoring the French and German students who had shared dormitories in continental Europe before 1914, they hypothesized that wars were the atavistic by-products of irrational nationalism rooted in a society’s most provincial and isolated lower strata. The only way to reform this primitive consciousness was from a society’s elites downward; the way to widen the horizons of the world’s directing elite was to bring them physically together in the common setting of the university which, they presumed, was not an arena of conflictual politics. While, particularly in the immediate postwar period, corporate internationalists acted in the name of peace, they fastened and often subordinated pacifist idioms to projects in the expansion of U. S. corporate power through the training and familiarization of foreign engineers, salespersons and administrators in U. S. techniques and products for potential export: world peace and unobstructed flows of capital and goods would be commensurable if not identical aims.41 If evangelical migrations principally linked the United States and Asia in the early 20th century, corporate-internationalist networks would stretch most thickly between the United States, Europe and Latin America. Their most prominent institutional hub was the Institute for International Education (IIE), founded in 1919, which connected interested students and universities with funders, primarily the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, the Carnegie Corporation and Rockefeller.42 But similar networks of student migration would also be sponsored by private, corporate civil society organizations like Rotary International.43 On the demand side, corporate-internationalist migration appealed to the bourgeoisies of industrial and industrializing societies that hoped either to draw adaptable insight from the United States’ technological and productive supremacy, or to seek employment in U. S. corporations that were greatly expanding in scope in the post-World War I period.44

All four types of global educational endeavor—and their cross-pollinations—hit snags. Would-be self-strengtheners could find themselves socially and politically isolated rather than empowered on their return home, their imported ideas becoming suspect when they collided with nativist and exceptionalist conceptions of the proper order of things; they sometimes also found that pre-emptive self-colonization did not necessarily stave off the real thing. Corporate-internationalists found that long-standing cultures of capitalism, industry and commerce in their home societies could prove stubborn soil in which to transplant American practices and institutions.45 The proximity to the U. S. metropole wrought by colonial and neo-colonial migrations could foment disaffected, nationalist sentiments as easily as solidarities. Evangelical students frequently expressed their shock at the looseness of American sexual morality and the vulgarity of American materialism.46 Indeed, students brought to the United States as either converts or colonial protégés often experienced what might be called metropolitan letdown: the deflation of the utopian images used to attract them to the United States upon sharp encounters with American realities.47

During this period, some of the starkest limits were expressed when foreigners—especially, it seems, Asians—petitioned Congress for admission to U. S. military academies. When in the 1870s, requests by Qing officials for the admission to West Point of two students from the Educational Mission were refused, it helped triggered the collapse of the program. In Spring 1906, with tensions between the United States and Japan on the rise, Congress barred foreigners from entering the Naval Academy.48 In March 1912, during a discussion of the admission of a Cuban to West Point, Senator Gallinger of New Hampshire took the opportunity to rail against foreign admissions more generally. “I doubt the wisdom of educating these young men, who possibly may become troublesome to us in time of war,” he was quoted as saying. “I am not sure that it is good policy to educate representatives of the warlike Chinese people, who number four hundred or five hundred million.”49 (The Cuban was admitted.) Such fears even extended to people who were not technically “foreigners.” In 1908, Senator Slayden of Texas objected to the idea of Filipinos at West Point on the grounds that such trainees might return home to foment revolution in the Islands.50

The cause of networked affiliation was also not helped by rising barriers to immigration.51 Students from China and Japan had been legislatively class-exempted from late-19th and early 20th century exclusion laws, alongside merchants, tourists and diplomats, but in administrative practice, port authorities tended to see in traveling Asian students well-disguised “coolies” seeking illegal entry, and more than one aspiring undergraduate found themselves detained at Angel Island.52 Much to the frustration of both educators and students, international interest in U. S. education was on the increase just as barriers to migration were rising. The restrictive 1924 Johnson-Reed Act did not exempt visiting students from its rigid quota system, and students could find themselves harassed, arrested or deported if they happened to arrive after their country’s annual entry quota had been filled.53 The Institute for International Education and Committee on Friendly Relations intervened to mitigate these rules and to buffer students from their application, greeting students at ports of entry to smooth over relations with officials and lobbying for quota exemptions for bona fide students in exchange for tighter, university-mediated certification regimes.54 Due to the success of these efforts, restrictionist legislation and administrative practice did not quash student migration—the region/race most intensely targeted by this legislation, “Asia,” was still sending the United States half of its international students in the mid-1930s—but they did make it far more complex logistically and, when it came to the goals of diffusion and legitimation, far more alienating. For much of the 20th century and into the 21st, things would get complicated where students found themselves at the cross-currents that roiled between the global politics of inclusion and exclusion.

That said, by the 1930s, the United States was already clearly emerging as a magnetic hub for student migration. While statistics for the early period were haphazardly collected, they demonstrate a pattern of growth and diversification, with a particular takeoff in the 1920s. In an informal, early census conducted in 1905, only nine colleges registered foreign students; by 1912, 37 colleges did.55 By 1930, when the Committee on Friendly Relations was conducting annual surveys, foreign students attended about 450 colleges and universities; by 1940, the number had grown again to 636. Reported overall student numbers grew from about 600 in 1905 to about 1,800 in 1912 to nearly 10,000 in 1930. Throughout this early period, the largest sending macro-region was Asia (led by China, Japan and the Philippines), followed narrowly but consistently, until a dropoff in the 1930s, by Europe (led by Russia, Germany and Britain), and then by North America, especially Canada. Central and South America followed, with comparatively small but growing numbers arriving from Africa, the Middle East and Australasia. While no gender statistics appear to have been collected prior to the mid-1930s, in 1935, 22% of foreign students registered by census-takers were women, a figure that appears to have been relatively stable for those years, although specific percentages varied by national origin.56

The rising threats of European fascism and Japanese militarism ushered in a second era in the history of student migration to the United States characterized by both deeper state engagement and geopoliticization. To this point the federal state had, through immigration law, arguably inhibited student flows at least as much as it had cultivated them. Its promotional energies had been confined to colonial and neo-colonial migrations—the Philippine and Chinese experiments—and earlier programs associated with the Belgian Relief Commission and the education of French veterans in the United States during and after World War I. Also prior to this period, there was no particularly strong relationship between diplomatic “friendship” and student circulation: in the 1930s, for example, the Soviet Union consistently sent more students to the United States than did any other European country. In contrast, by 1945 student migration patterns had begun to align with the United States geopolitically: through financial support, program administration and the granting of visas the State Department, often working through the IIE, drew student-allies close, beginning in the late-1930s and into the 1940s with the sponsorship of Latin Americans, and European and Chinese refugees. Perceived student-enemies, especially those of Japanese descent, whether U. S. citizens or otherwise were, as threatening “foreigners,” punished and isolated.57 While the mechanisms were varied, student circuits had begun to resemble wartime patterns of alliance and enmity.

The immediate postwar decades saw the explosive growth of student migration to the United States measured along every axis: in the sheer scale of student numbers, in the breadth of sending countries, in the proliferation of sponsoring programs, and in the numbers of receiving colleges and universities. From a total of 7,530 in 1945, student numbers doubled by 1947, then again by 1951, again by 1962 and yet again by 1969, reaching over 120,000 that year.58 The mounting gravitational pull of U. S. colleges and derived from many causes. The massive expansion of American higher education during these years presented foreign students with an appealing array of programs and fields of specialization. In war-torn and occupied stretches of Europe and Asia, the demand for reconstruction pushed further than “self-strengthening” ever had: centers of higher education had been destroyed, promoting an external search for the technical skills and resources required for social reconstruction. With the advent of decolonization, elite youth from newly-independent societies would be drawn to U. S. colleges and universities in pursuit of technical, policy and institutional frameworks suited to the building of modern, robust nation-states; for some, this represented a self-conscious alternative to colonial-metropolitan transits.

By 1960, a unitary sense of the category “foreign student” buckled before the varieties it was intended to contain.59 As Kenneth Holland, president of the IIE, noted in 1961, while twenty-five years earlier it had been customary to speak of “’the foreign student’” as if they shared “the same interests, the same needs, and even the same peculiar quaintness,” what impressed him now was “the fact of diversity.” The rising significance of international students to U. S. colleges, universities and public life, however, was unmistakable. Although the United States, as surveyed in 1959-1960, received a far smaller percentage of foreign students relative to its total enrollments (1.5%, as compared Morocco’s 40%; Switzerland, Austria and Tunisia’s over-30%; the United Kingdom’s 10.7%, and France’s and Germany’s 8%, for example), the United States attracted more total foreign students that year (48,486) than any other single country. In 1959-60, 1,712 institutions of higher education in the United States reported having enrolled foreign students; eighteen of these reported over 400 students and five of them (the University of California, New York University, the University of Minnesota, Columbia University, and the University of Michigan) had enrolled over a thousand.60

A Filipino woman named Egdona (shortened to Dona) gives a suburban family a lesson in Philippine dance. This photograph was an illustration in a December 1961 article in Parents’ Magazine that encouraged families to welcome foreign students and visitors into their homes. “Maybe you can’t travel, but you can bring the world to your door by opening your home to foreign visitors,” it stated. From the 1920s onward, but particularly during and after World War II, numerous commentators voiced their hopes that the presence of international students in the United States might cultivate a “cosmopolitan” outlook among Americans. From “Discovering the Rest of the World,” Parents’ Magazine, December 1961. Special Collections, University of Arkansas.

About half of the arriving students in 1959-60 were undergraduates, while the rest were graduate students or identified as “special students.” About 41%, a number that was on the rise, received outside financial support (more graduate students than undergraduates); although government aid was growing, state grants only made possible a small percentage of student exchanges (about 7.5%). Students’ specialties varied by region, but engineering predominated, followed by the natural and physical sciences (particularly for students from Asia, the Middle East and Latin America), humanities, social sciences and business administration. Students came from a total of 141 countries and “political areas”; the largest national contingent was, as it had always been, Canadian (12%), but the next six largest national groups were from the “Far East” and “Near East,” beginning with Taiwan and Hong Kong (9.3%) and India (7.8%); with Iran, Korea, Japan and the Philippines each exceeding 1,000 students (or about 2%). While students identified as being from Africa comprised a small proportion of the foreign student population in 1959-60 (about 4%, one quarter of whom were from the United Arab Emirates), this population would quadruple by 1967.61

Government involvement and geopoliticization only intensified in post-World War II period, by which point student migration became surrounded by, and to some degree embedded in, a much broader state practice that came to be known generically as the “exchange of persons.”62 Facilitated by the declining cost of long-distance commercial air travel, “exchanges of persons” involved U. S. government-sponsored visits to the United States by “identified” leader-counterparts from other countries—and movements by Americans in the opposite direction—for the purposes of diffusion and legitimation. It built on prewar and wartime Latin American precedents, but magnified them geographically and bureaucratically: in the postwar period, a plethora of government agencies, from the State Department to the Department of Agriculture, many initially associated with the Marshall Plan, undertook such efforts and employed them to connect to a much larger world that previously. In some respects, student migrations resembled “exchanges of persons” like the State Department’s Foreign Leader Program, but the student presence was vaster in scale, longer term, less centrally administered and funded, and less directly controlled. If there were official confusions between these categories, it was in part because participants in exchange programs were in many ways considered “students,” whether or not they were enrolled in school.

In strictly numeric terms, the largest number of exchanged persons—if not exactly “students”—were military trainees. After World War II, the U. S. government’s education of foreign military personnel, affiliated with the Military Assistance Program (MAP) was greatly expanded, streamlined and systematized, some of it taking place at the U. S. military academies, but the majority at other military schools, bases and facilities inside and outside the United States.63 The Latin American Ground School, for example, founded in the Panama Canal Zone in 1946 and later renamed the School of the Americas, would train tens of thousands of military officers from Latin American client states in counter-insurgency techniques that included torture.64 Such training was closely tied to arms transfers to foreign governments through either grants or sales. It sought, on the one hand, to shore up American global power by providing what researcher and advocate Ernest W. Lefever called “security assistance”: “promoting stability within and among participating states… by enhancing their capacity to defend themselves.” It was also directed at what Lefever called “our larger political interest,” which he expressed, interestingly, in classic “internationalist” terms: “strengthening the bonds of mutual understanding through a person-to-person program that has introduced thousands of actual or potential foreign leaders to American life and institutions.”65 By the 1970s, the cartography of military training mapped well onto the structure of U. S. global power, with roughly equal numbers of military trainees from Western Europe, East Asia and Latin America (between 70,000-80,000 each, most of them brought to the United States), and over 150,000 from Southeast Asia, most of them trained in the region. “Never before in history,” Lefever claimed, “have so many governments entrusted so many men in such sensitive positions to the training of another government.”66 By 1973, he estimated that the military had trained 430,000 foreign nationals, approximately twice the number of Fulbrights granted to foreign nationals between 1949 and 2007.

The state’s growing investment in a geopolitical sense of student flows was powerfully illustrated in the early 1950s with respect to Chinese student-migrants. Facing the imminent collapse of the Nationalist Government and the cut-off of both state and private supports, Chinese students in the United States were initially provided emergency assistance by the State Department, and encouraged to return to China as “future democratic forces” that would, according to two members of Congress, be “in a unique position to exert a profound influence on the future course of their country.” With the outbreak of the Korean War, however, this diffusionist project was slammed into hard reverse, and students were barred from returning to China precisely on the grounds that their technical knowledge might now help strengthen and modernize the economy of a Communist enemy. Facing financial crisis, trapped in a legal black hole and stigmatized as crypto-Communists, Chinese students were eventually “offered” legal status most could not refuse; the majority remained in the United States. The State Department negotiated the return of the rest as a trade for Americans held by the Chinese state, a practice which gave “exchange of persons” new meaning.67

Alongside with selected curtailments, the state became far more actively involved in facilitating and promoting student migration in the post-World War II period. While only a fraction of international students received direct financial support from the U. S. government, the state also came to play significant yet indirect roles. For one, it helped sponsor the professionalization of foreign student advising: prior to World War II, the only official attention most colleges paid to foreign students as such was to assign them, often haphazardly, to an interested professor. As a result, students often had to navigate a bewildering array of concerns—immigration laws, admission and certification procedures, curricular decisions and language issues, among them—more or less on their own. But beginning with a 1942 conference in Cleveland organized by the IIE in cooperation of the State Department, the Office of the Coordinator for Inter-American Affairs, and the U. S. Office of Education, foreign student advisors forged a profession with its own organization (the National Association of Foreign Student Advisors, or NAFSA), defining themselves through their advocacy for both students and student programs, and their knowledge of labyrinthine federal regulations and a proliferating social-scientific literature on students’ “adjustment” and “attitudes.” NAFSA, in turn, would push for the simplification of immigration procedures and convince authorities to delegate some certification tasks to advisors themselves.68

The state’s most direct and immediate postwar interventions in international education were in “re-education”: the inculcation of “democratic” and “anti-militarist” values in conquered German and Japanese citizens.69 But the archetypal post-World War II “exchange of persons”—one that included not only students, but scholars, educators and experts—was the Fulbright Program, heralded by the New York Times in October 1947 as “the most comprehensive program of student exchange ever undertaken by any nation.”70 The project was inaugurated in September 1945 with Arkansas Senator J. William Fulbright’s amendment to the Surplus Property Act of 1944, “a bill authorising use of credits established through the sale of surplus properties abroad for the promotion of international good will through the exchange of students in the fields of education, culture and science.”71 Cast then and since as a literal swords-into-plowshares endeavor, it authorized Congress to enter into agreements with foreign governments for the sale of abandoned “war junk,” the credits for which, administered by bi-national commissions, would used to fund educational travel to and from the United States. By 1964, the program stretched to 48 countries, and had involved the participation of over 21,000 Americans, and over 30,000 citizens of other countries.72

Framed in a language of mutual understanding, the Fulbright Program was also from the outset an exercise in power. In a brilliant exploration of its early formation, Sam Lebovic maps the politics at the core of the early program’s practice and rhetoric: American officials’ insistence on bulk sales of both usable and unusable “war junk” to fund the program; a sense of “educational exchange” as equivalent to other “intangible benefits” to be gained in return for the sales (alongside landing rights, commercial concessions for U. S. airlines, property for embassies and free trade agreements); and successful attempts to secure U. S. majorities, many of them with close ties to the U. S. state, on commissions that were ostensibly “private” and “binational.”73 Whether through Americans’ sponsored travels abroad, or foreigners’ visits to the United States, the Program’s goal was a world made safe for American leadership through the diffusion and legitimization of “American” values and institutions.

Fulbright was himself quite clear about the Program’s foreign policy implications in a 1951 article that expressed its goals in a Cold War idiom. Strikingly, the program’s primary end was “not the advancement of science nor the promotion of scholarship,” but “international understanding,” which Fulbright defined as the two-way breaking down of national stereotypes, with an emphasis on foreign exchangees as vectors of affirmative imagery of the United States. Of the carefully-chosen example of a Greek doctor who, having recently studied at the Mayo Clinic, had set up a successful hospital in Tyre, he inquired: “Cannot we expect a man like this to be influential with his friends and neighbors—and his 40,000 patients—in their attitudes toward America?” He concurred with Soviet charges that the program was a “clever propaganda scheme”; it was, indeed, “one of the most effective weapons we have to overcome the concerted attack of the Communists.” It did so in effect by turning the whole of American society into a USIA broadcast of sorts, based on the belief that “when foreigners come to our shores, what they see will be good.” Despite what he acknowledged were the nation’s “occasional strange aberrations,” Fulbright believed that if free world peoples understood the United States, “they will throw in their lot with us.”74

While the Fulbright Program clearly drew on and helped to shape post-World War II “internationalist” practices and ideologies, it also involved the synthesis and amplification of older educational migration forms, practices, institutions and discourses. In its sense that educational circuits could cement global power relations, it self-consciously looked to colonial and neo-colonial migrations. Fulbright would, for example, cite as sources of inspiration both his experience of the Rhodes Scholarship—that great imperial in-gathering of Anglo-Saxons—as well as the Boxer Indemnity Remission scholarships, which had helped develop what he referred to as Chinese-American “friendship.” Missionary idioms and impulses—secularized and nationalized, to be sure—were also present, in the hopes that Fulbright scholars, moving to and from the United States, might be agents of both the diffusion and vindication of universal American values. Closer still to the Fulbright’s surface were corporate-internationalist migrations, whose organizing principle had been that war could only be prevented and “progress” realized through cross-cultural understanding, which itself could only be accomplished through the proximity and “exchange” of enlightened elites. Not surprisingly, the program would be administered by already-existing private organizational agencies most responsible for giving life to these discourses over the previous twenty-five years, especially the Institute for International Education. Perhaps most vitally for an era of reconstruction and nation-building, the Fulbright program cast itself as the supply-side of self-strengthening, providing the universal techniques and capacities required to construct legitimate nation-states.

The issue of nation-building was pressed forward by the postwar collapse of European colonial systems and the emergence of independent nation-states in Africa and Asia; both sent students to American colleges and universities in search of both the technical skills with which to modernize their societies’ economies and infrastructure, and of political and social science models of development. Writing in the New York Times in 1960 of Asian societies, for example, Harold Taylor observed “a desperate need for educated leaders—in the foreign service, in domestic affairs, in medicine, transportation, industry and, above all, in education itself.” For Taylor, Asia’s modern universities were “not merely repositories of knowledge and communities of scholars”; they were, instead, themselves “agencies of social change.”75

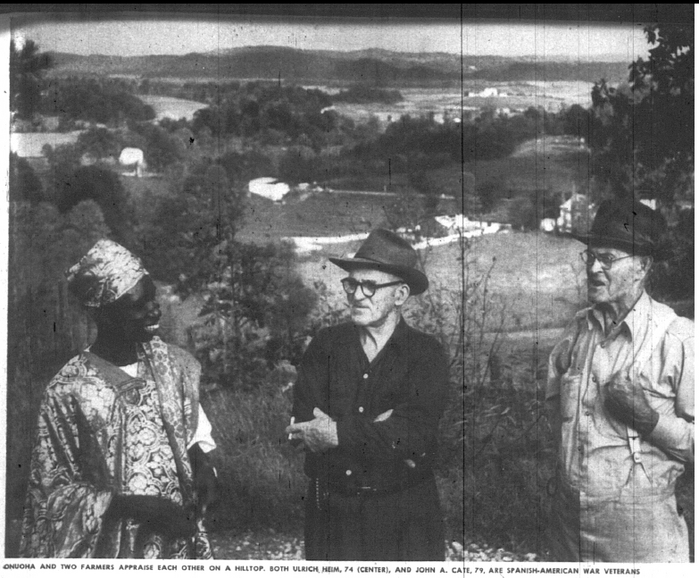

Geoffrey Baba le Onuoha converses with two Tennessee farmers, Ulrich Heim and John A. Cate, both Spanish-American War veterans, in 1954. A Catholic-school educated, secondary school teacher and postal telegraph clerk in Lagos, he was inspired to study in the United States by a USIA pamphlet on the Tennessee Valley Authority, and came to attend Morristown Normal and Industrial College, a small, all-black junior college and high school maintained by the Methodist Church. From “Onuoha and the Good People,” Life 37 (November 8, 1954).

In this context, he called on the U. S. government to provide supports—from translated American classroom and library materials to educational exchanges—to university students in Asia, who had “shown their readiness to assume responsibility for building a new society.” While Taylor himself de-emphasized Cold War competition, many others (including, as we’ve seen, the Nigerian students) referenced the Soviet Union’s education of the youth of decolonizing societies and, in particular, Moscow’s Patrice Lumumba Friendship University, opened in 1960. While American educators and journalists tended to minimize the Soviet educational threat by emphasizing reports of Soviet discrimination against international students of color and student disillusionment with the communist project, the very presence of competing Soviet educational circuits nonetheless heightened a sense of international education’s geopolitical urgency.

The potential political stakes in winning the youth of the Third World were on display in a 1960 project to bring 250 students from Kenya and other British-controlled areas of East Africa to U. S. colleges and universities. The effort, coordinated by labor leader Tom Mboya, was the largest such educational “airlift” to that point, but $100,000 in promised transportation funds from the State Department fell through at the last minute, jeopardizing the students’ Fall enrollments. In trying to make up the shortfall, Mboya had the good fortune of a competitive U. S. presidential race: he first approached Richard Nixon, whose overtures to the State Department were rebuffed, then John F. Kennedy, who possessed both private wealth and an eagerness to demonstrate support for African independence, in part as a way to send positive messages to African-Americans that did not involve binding civil rights commitments. The resulting “Kennedy airlift” was produced by a unique confluence of events, but suggested the broader ways that, at particular junctures of global and domestic U. S. politics, student migration could emerge as at least a symbolic priority. It did not, however, not solve the problems of the Kenyans who, like many foreign students, faced poverty in the United States.76

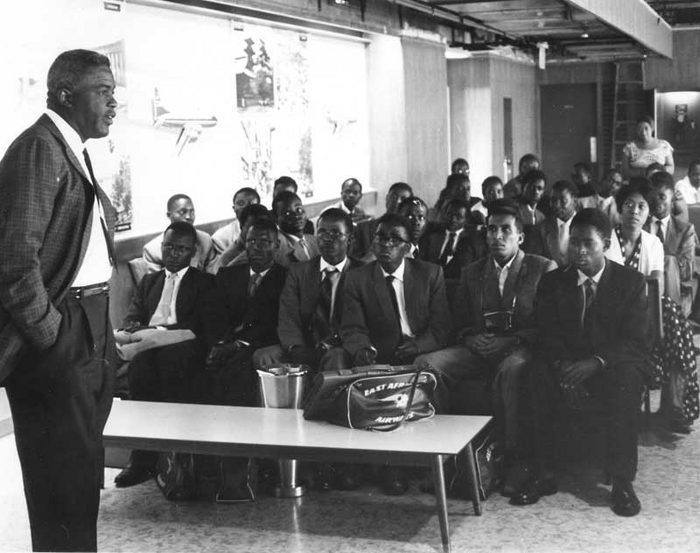

Baseball legend Jackie Robinson, who backed efforts to bring African students to the United States, greets the first “African Airlift” arrivals in New York in September 1959. Photo by Daniel Nilva for the African-American Students Foundation. Courtesy Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Jackie Robinson Papers.

It was in the context of increasing investments by the U. S. state, expanding student numbers, global decolonization and Cold War rivalry that what were long-standing emphases on foreign students as future leaders and potential instruments of American power reached their apogee.77 “In the cold war race to control men’s minds and hearts,” stated the Chicago Defender, in what would become a commonplace, “the foreign student occupies an important place.”78 Writing in May 1954 in defense of the Smith-Mundt Act, which partially funded foreign student exchanges, Walter Lippmann similarly drew a tight connection between foreign students and the fortunes of U. S. global power. Attracting, training and aligning the elites of the decolonizing world, he maintained—the Nigerians in Switzer’s parlor, in a sense—held the key to victory in global Cold War competition. “In any true estimate of the future of the enormous masses of mankind who are awakening, who are emerging from bondage and from ancient darkness, from foreign and native domination,” he wrote,

we must presume that the educated class can be, and will be, certain to decide their direction. From these elite will come the politicians, the civil servants, the military commanders and the industrial managers of these new countries. What these key people know, and what they believe about themselves and about the rest of the world, is the inwardness of the whole vast movement of historical forces.

The key to U. S. dominion—Lippmann’s focus was Asia and the Pacific—was the affective capture of these aspirants and their training in “the universal principles of freedom.” As long as the United States did not become “alienated from the educated class,” a “new order of relations between Asia and the West” was possible. “If that alienation is allowed to happen,” he warned, “as some of our stupidest philistines do their best to make happen—armies and weapons and pacts and money will be of no avail.”79

While the hope of turning student flows into networks of influence was more consistently articulated during the post-World War II period, this did not make the goal any easier to realize in practical terms. For one, there were institutional tensions that had to be worked out in the corporatist nexus between state and private agencies. To be sure, there were abiding reciprocities here: since the late-1930s, private organizations like the IIE had turned eagerly to the state for sponsorship, and state agencies had looked to the educational private sector initially as an administrative necessity and, in the postwar period, as a virtue: the private-sector face of international education either distinguished the U. S. state’s “cultural” programming from “propaganda”—the informational praxis of the Communist other—or, at the very least, projected the image of non-propaganda. (It was telling that the distinction here was often not drawn very clearly.)

But while the interests of state and private-sector proponents partly overlapped, there were also places where they failed to fully align. Whether for reasons of professional autonomy or “internationalist” sensibility, university educators and foreign student advisors, for example, tended not to share the State Department’s enthusiasm for fusing “educational” and “informational” programs.80 Indeed, educational associations lobbied actively for the formal separation of these functions; Laurence Duggan, head of the IIE beginning in 1946, for example, wrote to the Assistant Secretary of State expressing his concern that student fellowships “must not be a means whereby out government hopes to influence foreign students in the United states in favor of particular policies and programs.”81 While the division here was not trivial, it sometimes mapped onto the distinction between debated means and agreed-upon ends or, put temporally, between “short-term” and “long-term” strategies: many if not all international educators expressed hopes that the fragile desiderata of diffusion and legitimacy might be realized, perhaps more slowly, on their “own,” while they might be threatened precisely by too heavy an “informational” hand. The struggle appears to have been resolved through nominal concessions to “educational” autonomy. The State Department’s Office of Educational Exchange established two sub-divisions, the “informational” Division of Libraries and Institutes and the “educational” Division of International Exchange of Persons that, in practice, worked closely together.

There was also, more fundamentally, the problem of the U. S. state’s political and financial support for “student exchange” in the first place. While its advocates advanced anti-Communist arguments, so did its detractors: Senator Joseph McCarthy, among others, saw in such programs the undesirable government-sponsored attraction of student-subversives to American shores. While the 1947 United States Information and Educational Exchange Act, or Smith-Mundt Act, had authorized annual Congressional appropriations to support educational and cultural programs, throughout the 1950s, Congress sliced back requested budgets for educational exchange programs (even as “informational” budgets grew), prompting public campaigns in their defense by a wide range of educators, journalists and political figures. While never merely instrumental, the Cold War idioms of advocates like Fulbright and Lippmann should be read in part in the context of budgetary battles they often lost. Supportive presidents made a difference: the Kennedy administration’s activism in defense of educational exchange, together with a more hospitable Congressional environment (one that included Fulbright as the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee), made possible the passage of the transformative 1961 Fulbright-Hays Act which, implementing the suggestions of a task force in which NAFSA had played a key part, was to provide funds to improve and extend services, training and orientation programs for international students.

In two major shifts, Fulbright-Hayes dramatically widened the scope of government support to all international students, rather than just U. S. government-financed ones (who made up less than 10% of all international students), and simultaneously shifted program rhetoric from the Smith-Mundt Act’s pursuit of “a better understanding of the United States in other countries” toward a new emphasis on promoting “mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries.”82 The 1966 International Education Act, sponsored by the Johnson administration, similarly authorized ambitious programs for both the support of international students in the United States and the expansion of international studies programs on American college campuses. But in both cases, Congress failed to appropriate the necessary funds. By the late 1960s, Johnson’s internationalism was focused violently on Southeast Asia; educational priorities among both politicians and philanthropists were turning towards domestic, Great Society project from which, many assumed, international students might drain resources. While vocal, the student exchange lobby could ultimately not compete with these other agendas. And perhaps it was also the case that, by the late-1960s, college campuses themselves seemed sub-optimal as settings for the inculcation of consensual, Cold War values.

Finally, there was the problem of audience: foreign students could not be made into agents of American power successfully (if at all) without their also becoming witnesses. Indeed, from early in the 20th century, proponents of international education had concluded that, in causal terms, legitimacy came before diffusion: students would scarcely desire to transmit the practices, values and institutions of a society that they had not come to respect. While Fulbright and others confidently assumed that the warm bath of American society would (mostly) on its own vaccinate international students against Communist doctrine—or even dissolve ideological encrustations—the problem of student attitudes towards American society also became one of heightened concern in the 1950s and 1960s. “What these foreign students think of us may matter even more in the future than it does today, for they are a picked group,” the author and editor W. L. White observed in 1951, noting that the current President of Ecuador, the Lebanese chairman of the UN Human Rights Commission, Afghanistan’s General Director of Labor, and the Guatemalan Minister of Commerce, had all once studied in the United States. Presuming a vertical, diffusionist model of society, observers then assumed that this American-trained global elite would automatically and successfully transmit its perceptions throughout society. “Soon they will return to their native lands,” wrote White, “spreading over the earth’s six continents what they now are seeing, learning and feeling about America.”83 Impressions received would be “carried back to the universities and shops of their homelands,” predicted the New York Times, “to be spread, if good, like bountiful propaganda; if bad, like a festering virus.”84

If this anxiety was animated in part by the growing presence of foreign students in American colleges and campus communities, it also coincided with the advent of foreign student advising as its own profession. If they did not exactly invent what was sometimes called the “foreign student problem,” advisors would play a unique role in defining and addressing it. And many came asking: throughout the 1950s and 1960s, surveying the attitudes and opinions of international students developed into something of a cottage industry among educational agencies and academic social scientists and their graduate students. As research, it had the advantages of apparent novelty, “naturally” divisible populations (often delineated either by campus, or by nationality or region of origin, or both) and, without too much difficulty, a sense of geopolitical relevance, often front-loaded in introductions. In surveyors’ queries, one can read a landscape of curiosity and vulnerability: a self-consciousness and sensitivity about American political systems, consumer cultures, gender and sexual norms and, closest to home, about college institutions and attitudes about foreigners. While students’ responses were, of course, bounded by the questions asked, the surveys and studies that resulted from them also registered them as agents upon whose opinions of American society, at a particular global conjuncture, a great deal seemed to hinge. If students were a probing audience to American society, including to what Fulbright himself had elusively called the “occasional strange aberrations” in American life, the problem became how best to direct students’ attention, insulating them from Lippmann’s “philistines” and failing that, managing students’ impressions of them.85

It was in this context that problems of race assumed great prominence. The Nigerians of McPherson, Kansas were not alone: throughout first two-thirds of the 20th century, approximately half of the students traveling to the United States were people for whom vacancy signs tended to vanish in American cities, and who could be casually consigned to the backs of buses throughout the South. And many students who were not directly victimized by race were onlookers: for 27% of students surveyed in 1961, it topped the list of American “shortcomings” (followed by “intolerance of foreigners”); 12% identified it as “personal problem.” Some students, prepared by mass media in their home countries, had braced themselves to witness and experience segregationist culture, although for 29% of those surveyed, things were worse on the ground than they had anticipated.86

International students frequently encountered signs like this one in bus and train stations and other public accommodations throughout the South, whether in residence there, or traveling through on vacations; students of color were often denied equal access to these facilities. When polled in 1961, students registered racial discrimination and “intolerance of foreigners” as among Americans’ chief flaws. Foreign student advisors worked constantly to mitigate discrimination and often explained it away as a limited, fading and superficial aspect of American democracy.

International students of color encountered forms of racial exclusion on summer travels and field trips—a site of particular trepidation for foreign student advisors—but also at the heart of campus rituals, as when, at a June 1924 college graduation ceremony in Colorado, white female graduates refused to march in pairs with Chinese male graduates who, as a result, were asked to march with each other.87 No problem was more immediate or intractable than the search for acceptable lodging in racially divided housing markets. One limited solution involved the formation of International Houses which, beginning in the 1920s, brought together American and international students under a single campus roof, simultaneously expressions of “international” idealism and cosmopolitan withdrawal in the face of residential segregation. “No one blinked at the fact that a lack of adequate housing and discrimination against foreign students were factors which made the Houses desirable,” wrote Gertrude Samuels of New York’s I-House in 1949.88

It was clear to many that foreign students—whether as sufferers or observers of racial discrimination in the United States—might take away with them impressions of democracy’s racial limits that might eventually jeopardize the nation’s legitimacy before world audiences. Especially in the post-World War II period, concerted efforts were undertaken to explain racial discrimination in the United States as a residual and gradually eroding reality, perhaps one of Fulbright’s “strange aberrations.” In December 1951, for example, the American Field Service, which coordinated year-long high school exchanges, took eighty European teenagers to the Harlem YMCA, where they “heard informal reports on various phases of Negro life in New York and in this country.” The presentations, by Edward S. Lewis, executive director of New York’s Urban League; Thomas Watkins, editor of the Amsterdam News; and two officials from the Harlem YMCA itself, told of “continued discrimination and gradual progress.” Lewis stated outright that the program’s purpose was to address what he called the “’weak point in democracy’s armor’” vis a vis Communist propaganda, and “to correct any stereotyped impressions among the visitors.” “’Why doesn’t the United States help its own people first, rather than worry about the rest of the world?’” one student asked. After noting that active efforts were underway to improve African-Americans’ standing in the United States, Lewis observed that “’Americans realize that what is happening in the rest of the world is just as important as what is happening in this country. We know that our survival as a nation depends upon what happens elsewhere.’”89

Rozella Switzer’s approach to these issues was somewhat more confrontational. Over the weeks following her kaffe klatsch with the Nigerians, she apparently “moved through McPherson as relentlessly as a combine.” Her “crusade” began with an urgent call to the department store manager, whom she persuaded, along with three other merchants, to align each of the students with the gift of a new suit, overcoat and gloves. Switzer then took her message—“’We’ve got a chance to whip some Communists, and all we have to do is act like Christians’”—to barber shops, the Ritz movie-house and even the American Legion, one of whose members she “buttonholed,” telling him, “’I’m going to make a decent guy out of you if it takes all next year.’”

Switzer met resistance, as when Shorty, the only barber in town that she had convinced to cut the Nigerians’ hair, was boycotted by white customers and criticized by preachers. But by the following December, when her story could be narrated as a modern-day parable of Christmas hospitality on the pages of Time (replete with the Nigerians, “some of them in native costume” caroling with other college students), Switzer’s (and the students’) “one-town skirmish” had achieved some modest results.90 Restaurants and the movie house had opened their seating to the Africans (although whether this extended to the town’s 23 non-African black people remained unclear); high school students in a social science class had gone “to check up on race relations” in the community. The Nigerians were still traveling 35 miles to get their hair cut, but local merchants had promised to “look into the barbershop situation.”91

For Time, the biggest change had been McPherson’s unconscious “cast[ing] aside its old measurements of comfortable solidity.” In this, the magazine predictably read the embattled world power into the tiny Kansas town. “”Challenged by a fragment of the world’s demand on the U. S., McPherson was trying—as a whole humble people was trying—to ‘act like Christians’ and measure up.”92 If the magazine’s desire to see the empire in small-town microcosm was misguided—as was its characteristic trumpeting of humility—the article also told the story of students who had managed, in a particular global context, to leverage the expectations and mandates of diffusion and legitimation, in whatever small ways, into recognition and opening. Unforeseen, unbidden and uneven, here, perhaps, was something like exchange.

While the dynamics of international student migration to the United States would change after the 1960s, in ways that can only be sketched briefly here, the debate on the presence of foreign students in American society would often remained grounded in geopolitical concerns. During this period, the labor and technical demands of newly-industrializing regions drew international students to American colleges and universities in unprecedented numbers. As many public universities experienced neo-liberal budget cutbacks, particularly during and after the 1980s, they became increasingly reliant on foreign student tuitions and enrollments to sustain revenue streams and the demand for key programs, especially in engineering, computer science and mathematics. Also over these decades, along with other new tasks that universities took on as service providers for corporations, they emerged as major placement centers for highly trained labor. For many observers, the United States’ very success in attracting, training and employing foreign students—in a progressively more competitive, global educational environment—was both an index and precondition of “American” national strength.

But this particular understanding of educational power would be challenged in the wake of terrorist attacks, particularly after September 11th and the realization that two of the hijackers, having entered the country on tourist visas, had been sent student visas at a Florida flight school.93 Calls for more aggressive government surveillance and monitoring of foreign students, understood by many to be a population disproportionately threatening to the “homeland,” were met with critical responses, particularly by university officials and foreign student advisors. Faced with burdensome new regulations (sometimes racially inflected in practice), they maintained, talented students would simply pursue options in more open societies and their labor markets; in doing so, they would strip American universities and corporations of their skills, and the larger consumer society of their actual and potential earning power. Updating century-old discourses, the proponents of openness argued that international students, in fact, enhanced American power, particularly as carriers of American practices and institutions, and of positive imagery about American society. “People-to-people diplomacy, created through international education and exchanges,” stated Secretary of State Colin Powell in August 2002, “is critical to our national interests.”94 The struggle between proponents of what might be called the empire of the homeland and the empire of the talent pool was not resolved during the first decade of the 21st century; the question of how deeply international students would transform both American global power and domestic society remained open. Some of them, and some of their children—one Kenyan-Kansan from Hawaii and Indonesia comes to mind—would go far.