“The World is beginning to know Okinawa”: Ota Masahide Reflects on his Life from the Battle of Okinawa to the Struggle for Okinawa

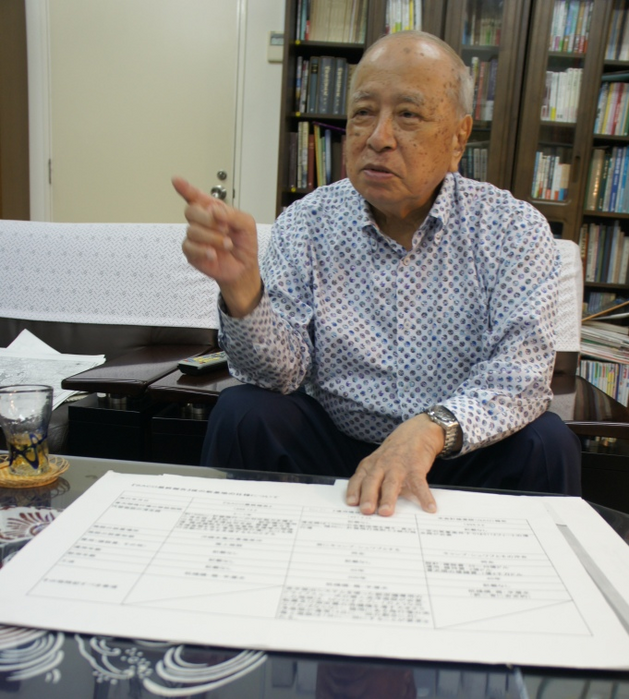

Ota Masehide and Satoko Norimatsu

Ota Masahide interviewed on July 20, 2010 at the Ota Peace Research Institute, Naha, Okinawa

Interview, translation, notes, and introduction by Satoko Norimatsu

The Japanese original text is available.

Introduction

“Ota-san is the ‘Conscience of Okinawa’,” the manager of a small museum in Shuri said, when I told her I was going to interview former Governor of Okinawa Ota Masahide after leaving the museum. The museum, run by the alumni association of Okinawa Prefectural First Junior High School (now Shuri High School), commemorates their students who perished in the Battle of Okinawa. At the time of the U.S. invasion of Okinawa in late March of 1945, at least 1,787 junior high school boys across the island, mostly from age 14 to 18, were drafted by the Japanese Imperial Army as members of the “Tekketsu Kinnoutai (Blood and Iron Student Corps).” At least 921, more than half of those students, died in the Battle, the bloodiest of the Pacific War, which took over 200,000 lives, half of them local civilians.1

Ota Masahide (right ) as a student at Okinawa Teacher’s College

Ota, a native of Kumejima Island, about 100 kilometres west of Okinawa Island, was a 19-year old student at the Okinawa Teacher’s College when he was mobilized as a member of the communication unit of the Tekketsu Kinnoutai. Almost daily, he saw his classmates bombarded and “die the deaths not of humans, but of worms.” 226 of his 386 schoolmates died.2 He spent the last months of the Battle hiding amongst the rocks of Mabuni Beach, surviving the hunger, thirst, injury and desperation.

The rocky shore of Mabuni, the last battlefield in the desperate war, on the southern tip of Okinawa Island. Ota survived the last few months of the war hiding amongst the rocks there.

The experience of the Battle left incurable scars on Ota’s mind, as it did for many Okinawans. When the Army left its Shuri Headquarters to retreat towards the south of the island in May 1945, an injured soldier begged Ota to take him along, saying “Gakusei-san! Gakusei-san! (student, student!).” Sixty-five years later, “I still hear the soldier’s cry every day,” Ota said. “There is so much unfinished business,” as there are still thousands of bones yet to be discovered, and unexploded bombs across the island that are expected to take 40 to 50 years to dispose of. Ota ponders, “The war is far from over in Okinawa. Then why prepare for more wars?” This sentiment is shared by many Okinawans. The islanders’ strong resistance against hosting U.S. military bases is inseparable from their experience of the indescribable horrors of a war that took more than one fourth of the lives of local people. They do not just want to see another war in Okinawa; many feel responsible for indirectly participating in current U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, by providing land for their military bases, however reluctantly.

Corpses of Japanese soldiers in the courtyard of Shuri Castle

The Battle also set foundations for Ota’s post-war endeavours. During his governorship (1990-1998), Ota set three goals as Okinawa’s peace initiatives: commemoration of the war dead and promotion of education and research for peace. The first two were achieved: the expansion and improvement of Okinawa Peace Memorial Park and Museum; and the erection of the “Cornerstone of Peace,” on which 240,931 names (as of June 23, 2010)3 of those who died in the Battle of Okinawa are inscribed, regardless of nationality, and of whether military or civilian. The last of the three-pillar project, the establishment of an “Okinawa International Peace Research Institute,” was suspended when he left the Governor’s office in 1998.

From the top of the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, overlooking the Mabuni Hill and the “Cornerstone for Peace (Heiwa no ishiji),” remembering all who died in the Battle of Okinawa, regardless of nationality, and whether military or civilian

Ota, the 85-year old sociologist and professor emeritus of the University of Ryukyus, now runs his own peace research centre in Naha, with six staff members, and tirelessly writes and speaks on behalf of Okinawa and its people, long-oppressed by Japanese and American colonialism and militarism. His interview on July 20, 2010 covered the emerging movement for Okinawa’s independence, the controversy over the forced mass suicides during the Battle of Okinawa, the “Futenma relocation facility” and media bias on the issue, growing worldwide interest in Okinawa research, and the importance of “making friends beyond the wall” to expand the network of international allies for Okinawa.

This report emphasizes the “Futenma relocation” issue, particularly elements that provide knowledge, background and perspectives that are not readily available in mainstream discourse. The Futenma controversy dates back to 1995, during Ota’s governorship. Ota, alarmed by the 1995 “Nye Initiative,” named for Assistant Defense Secretary Joseph Nye and calling for a strengthened U.S.-Japan security relationship, refused to sign documents by proxy that would force the landowners of U.S. military bases to renew leases. Okinawan rage erupted that year over the rape of an Okinawan child by three U.S. GIs, and talks started between Ota and the Japan/U.S. governments for return of the bases. Ota’s direct account on this issue gives special significance to this interview, in the context of the contemporary Okinawan struggle to close the dangerous base at Futenma while opposing the US-Japan plan to build yet another U.S. military base at Henoko in the Oura Bay on the northern coast of the island.

Norimatsu Satoko

On the “Futenma Relocation” and plans to build a new base at Henoko, Oura Bay

Ota Masahide interviewed in his office

A large, dangerous, expensive, and unneeded base

There has been a lot of media coverage of the Henoko issue (the Japan-U.S. plan to build a new base to replace Futenma Air Station), but none of those reports properly understand the historical background or the core issue. We have discovered some shocking facts from material collected from the U.S. National Archives.

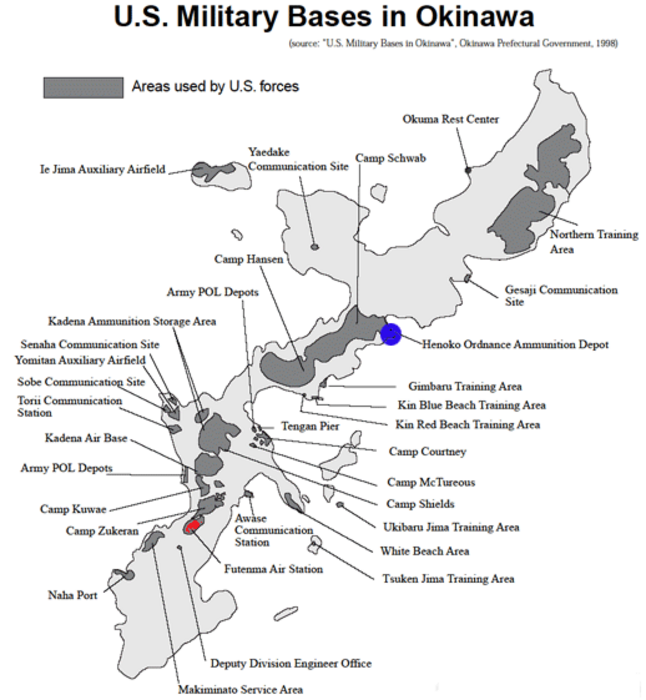

U.S. military bases in Okinawa – the blue dot is Henoko, where a controversial new base is planned to replace the Futenma Air Station (in red)

Let me give you some background. As early as 1965, the U.S. Government started behind-the-scenes talks about returning Okinawa to Japan. Many of the major U.S. military bases in Okinawa are situated in the mid-south region of the island, the most densely-populated area.

Before its 1972 reversion to Japan, neither the Japanese Constitution nor the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty applied to Okinawa. This enabled the U.S. military to bring nuclear weapons and biological/chemical weapons to the island. On July 8, 1969, 24 U.S. military staff members were exposed to poison gas leaked from the Chibana ammunition depot. The Wall Street Journal reported this incident, and it caused a huge uproar in Okinawa, igniting a movement to remove nuclear, and biological/chemical weapons.4 The ammunition depot had some goats in their field. Goats are susceptible to poison gases, so when dead or groaning goats are found on the ground, it indicates that poison gas has leaked. The local residents were not told about about the weapons or the incident.

The Wall Street Journal reported this because U.S. military personnel were affected. The chemical warfare munitions were moved out of Okinawa in 1971, in “Operation Red Hat,”5 but neither Japanese government representatives nor Okinawa’s Governor could enter the U.S. military bases without permission. No one checked whether all the weapons were removed. Even now, polls indicate that 60% to 70% of Okinawans believe that chemical as well as nuclear weapons are still stored on their island.

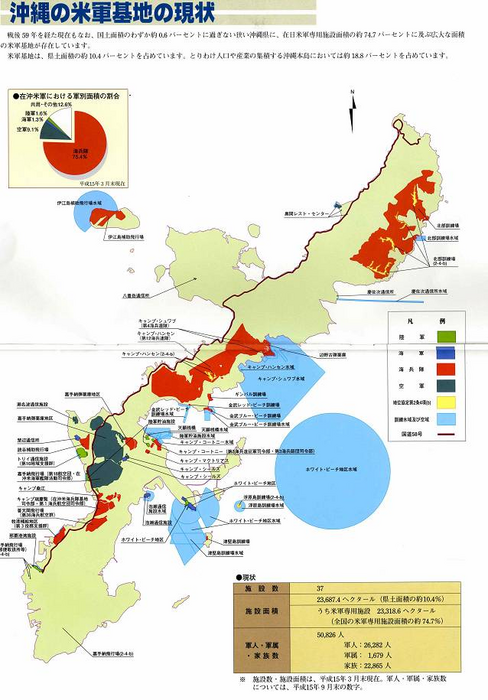

Map of US military bases in Okinawa. Red: Marine Corps; Dark Blue: Air Force (Kadena); Green: Army; Bright Blue: Navy; Light Blue: Water Space and Airspace for Training. 20% of Okinawa Island is occupied by U.S. military bases, of which 77% are managed by the Marines, but all four services maintain bases.

After Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972, the Japanese Constitution and Japan-U.S. Security Treaty were supposed to apply to Okinawa, so that there were supposed to be restrictions on how the U.S. military managed those bases. Gene R. LaRoque, a retired Navy rear admiral who founded The Center for Defense Information in Washington, dropped a bombshell in 1974 by stating that it was impossible for U.S. warships to unload nuclear weapons when they visited Japanese ports, because it would mean violation of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles (non-production, non-possession of nuclear weapons and not allowing nuclear weapons into Japanese territory). In 1981, former U.S. ambassador to Japan Edwin Reischauer disclosed that the two governments had signed a secret pact to allow the nuclear-armed U.S. vessels into the Japanese water and its ports.

Naha military port was under U.S. control as well as the military bases. What is now known as the National Route 58, which runs across Okinawa from the northern tip of the island all the way south to Naha along the western shore, was built by the U.S. military and was formerly called “Military Route 1.” The U.S. military would load tanks and artillery at Naha Port onto long trucks and transport them on this route to the Northern Training Area. Angry local residents tried to block the road, by standing in front of the trucks. The memory of the Battle of Okinawa was still fresh in the minds of those people, who did not want the island being used for war and war preparation ever again.

U.S. military forces in Okinawa feared that those protests would increase once Okinawa was returned to Japan and basic human rights, which were guaranteed under the Japanese Constitution, were applied to Okinawans. The U.S. wanted to consolidate the bases away from heavily populated areas – moving those bases south of Kadena Air Force base – to Henoko, Oura Bay. Naha military port was too shallow to berth aircraft carriers so they wanted to build a military port with a gigantic pier in Oura Bay, which had a depth of 30 meters, enough to accommodate aircraft carriers.

Oura Bay, overlooking Cape of Henoko, with Camp Schwab buildings in sight

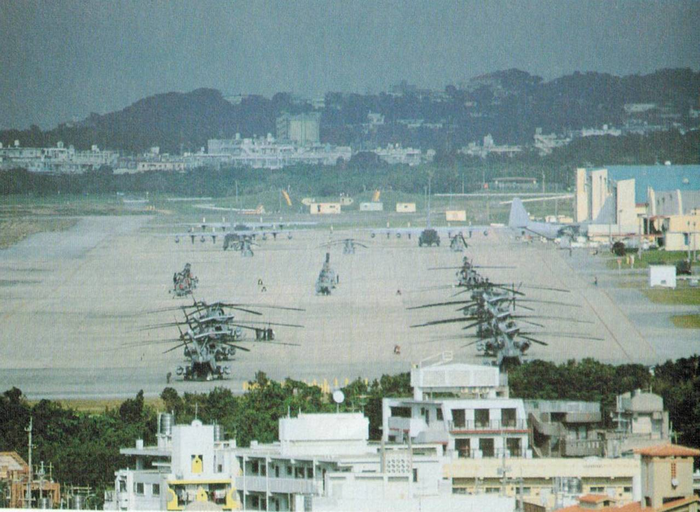

Futenma Air Station was also inconveniently located for the U.S. military. Futenma has a helicopter unit, which is a battle unit (the helicopter that crashed into the adjacent campus of Okinawa International University on August 13, 2004 belonged to this unit), and their helicopters have to go to Kadena to load ammunition, because Futenma is too close to residential areas. A new airbase in Henoko would allow the helicopter unit to load weapons on land, and also at sea. The plan to build a base in Henoko was hatched as early as 1965, and blueprints were drawn up in 1966 and 1967.

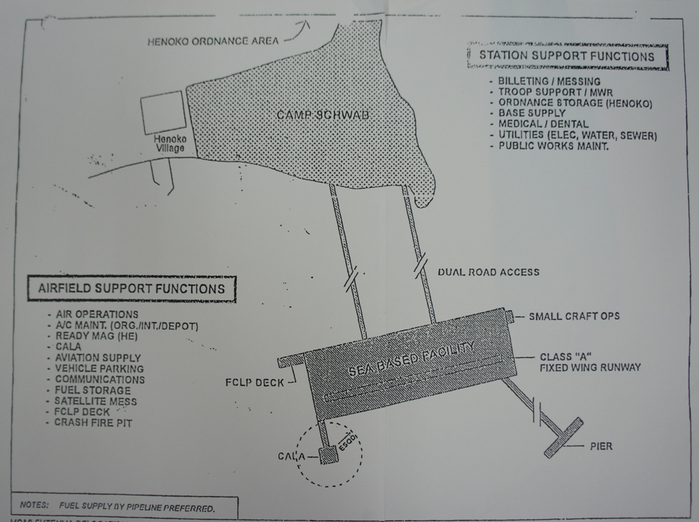

In 1966, the Navy and the Marine Corps commissioned Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall, a U.S. engineering company, to assess the wind direction and they drew this plan.

The 1966 U.S. plan to build a Marine airbase and a Navy military port at Henoko

Below is the plan made under the Hashimoto Administration, in 1997 (after SACO – the Special Action Committee on Okinawa report at the end of 19966). It was called a “Sea Based Facility.” The U.S. and the Japanese governments intended to build a base off the coast of Camp Schwab, connected by bridges and piers.

1997 “Sea Based Facility” plan

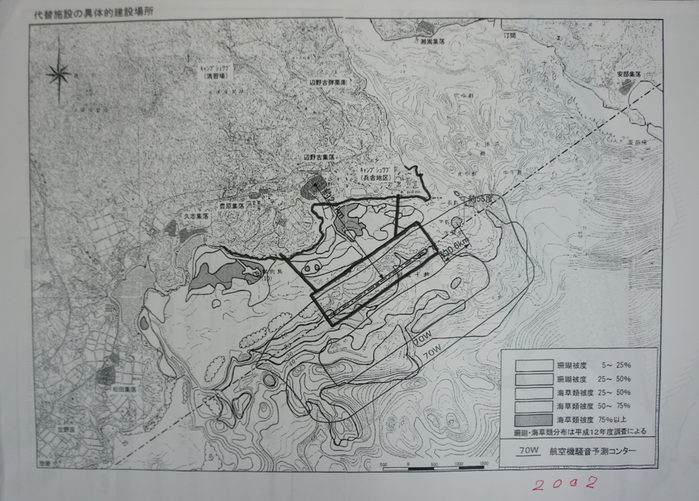

Below is the 2002 plan, which returned to the original location where the U.S. military wished to build the base in 1966. The sea-based, removable heliport plan of 1997 was transformed into a 2,000-meter runway on reclaimed land, two kilometers away from the coast of Henoko.

The 2002 plan for an off-shore runway built by reclamation

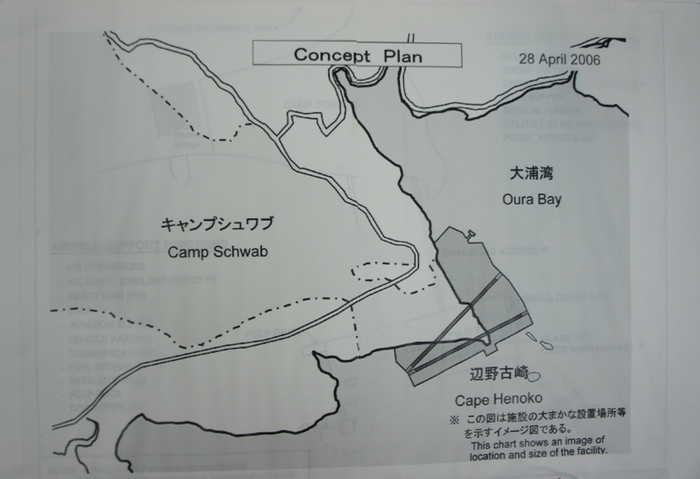

Now look at how this 2005 plan (below) resembles the original 1966 plan.

The 2005 L-shaped plan in the “U.S.-Japan Alliance: Transformation and Realignment for the Future,” October 20057

But other voices were calling for a base further away from the coastline, citing noise over the residential area as the reason. So Defense Agency Chief Nukaga Fukushiro came up with a V-shape plan as an alternative, claiming that one of the runways would be used for landing and the other for take-off, to avoid flying over residential areas. This is the plan in the 2006 “Roadmap” agreement: the V-shaped runway plan.8

The V-shaped runway plan in the Roadmap Agreement, 2006

Nukaga secretly met with former Nago Mayor Shimabukuro Yoshikazu, and worked out this plan, supposedly to reduce noise by having separate runways for take-off and landing. Because a single runway (the 2005 L-shape plan) would generate too much noise, there were calls to move the new base further away from the coastline. This led to the V-shape plan in 2006. As of now (July 2010), the two governments are again talking about building a single runway.

We (at the Ota Peace Institute) think that the plan will eventually be rolled back to the one of 1966. But why was the U.S. unable to proceed with this plan in 1966? The U.S.-Japan Security Treaty did not apply to Okinawa then, so the U.S. military would have had to pay for the relocation, construction, and maintenance of the new base. The Vietnam War was already becoming very expensive, and the U.S. dollar was depreciating. The U.S. simply could not afford this base and so put the plan on the back burner. Now, with the Japanese government ready to shoulder all the expenses, it is a perfect opportunity for the U.S. to revive the plan.

But I wonder how realistic all these “replacement” plans are. One recent idea was to build a Futenma replacement base on Iwojima Island. That made me laugh. Iwojima has no residents; there is only a Self Defense Force base. Supply of workers is essential for any military base, but Iwojima has no people. How could the U.S. accept this idea?

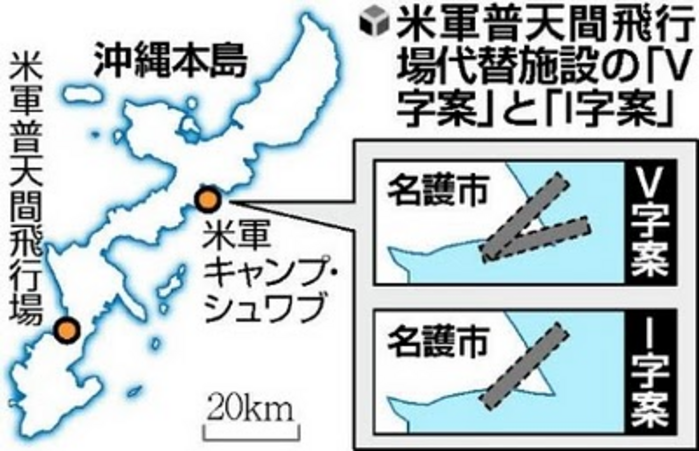

Futenma Air Station, the left dot on the map of Okinawa, and Henoko, Nago, the right dot. The “V-shape” plan and “I-shape” plan being discussed in 2010 by the Japanese and U.S. governments are diagrammed.

Although Nukaga managed to convince the U.S. to accept the V-shape runway, the soldiers in the field found it ridiculous. Once war starts, how can pilots pick and choose this runway for take-off and that runway for landing? It would be impossible.

The Japanese and U.S. governments want to build a base by reclaiming land adjacent to Camp Schwab. The governments prefer a base as close to Camp Schwab as possible, because it is off-limits to residents and construction can proceed without disturbance by protesters. Okinawa prefecture, however, wants the base as far away from the coastline as possible. Their official rationale is noise reduction for the residential area, but the truth is that the decision is driven by construction interests.

Pro-base construction interests in Okinawa have been sustained by the “gravel industry association.” The farther away they build a base from the coastline, the more gravel they need, as the ocean gets deeper. The current governor (Nakaima Hirokazu), the governor who succeeded me (Inamine Keiichi), and the previous Nago mayor (Shimabukuro Yoshikazu) were all elected with backing from the gravel industry. But when they tried to build farther away from the coast, environmentalists and peace activists dived into the ocean, pulled up the piles and disrupted the construction. This is why the government is trying to build a base near Camp Schwab.

85,000 Okinawans gathered in Ginowan, to protest against US military bases and GI crime on October 21, 1995, after the gang rape of a school girl by three US GIs.

The Japanese government is being called on to pay for the relocation and construction, but it has no idea what kind of base will be built. A Department of Defense report9 says the operational life of the base will be 40 years and the useful life of the base will be 200 years. The U.S. GAO (Government Accountability Office), which checks the budgets, estimates the new base will cost 1 to 1.5 trillion yen (approx. 10 to 15 billion U.S. dollars), and will take 10 to 12 years to build.10 On the other hand, the Japanese and U.S. government spokespersons are estimating 300 to 500 billion yen (approx. 3 to 5 billion dollars) and 5 to 7 years. There are great discrepancies between the GAO and the governments’ estimates.

Futenma Air Station, Ginowan, Okinawa, surrounded by residential areas, schools, and hospitals. Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld called it “the most dangerous military base in the world.”

Some young DPJ (Democratic Party of Japan) members of Parliament ask why billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money should be spent for the sake of Okinawa. I tell those people that we Okinawans don’t want any money, and they are welcome to take the base themselves. These people, knowing nothing, keep saying that a base should be built at Henoko. They don’t know what kind of base it will be or how much it will cost.

The current U.S.-Japan agreement plans to move 8,000 Marines and their 9,000 family members to Guam, with Japan paying 60% of the estimated cost of 10.2 billion dollars, that is, over 6 billion dollars. Now it looks as if this will cost a lot more than 10 billion. Recently, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates requested additional funding from Japan,11 saying the whole transfer would cost as much as 15 billion dollars. 60% of that would be 9 billion. If the Henoko base costs 10 to 15 billion, the total cost of the transfer to Guam and construction of a new base would be 30 billion dollars.

A Marine helicopter that crashed into the campus of Okinawa International University on August 13, 200412

The military base issue is not about security; it is about profit

According to Colonel Thomas R. King, former vice commander of Futenma Air Station,13 the purpose of a new base in Henoko is not just to replace Futenma Air Station, but to build a base that has 20% more military power than Futenma. A base in Henoko would enable loading of ammunition on land and from the sea. The new base would also host a dozen or more MV-22 Ospreys. Ospreys, which have caused frequent accidents in the U.S. and beyond, are called “widow makers.”

King estimates that it would take two more years to make it possible for Ospreys to operate safely on and around the new sea-based facility, so the construction of the base could take 12 to 16 years in total. The cost of construction will be10 to 15 billion dollars, and it will be as large as Kansai International Airport; enough to accommodate 35 aircraft. The annual maintenance cost of Futenma is 2.8 million dollars, but that for the replacement base in Henoko would be exponentially higher – as much as 200 million dollars. The runway of Futenma is 2,800 meters. The Japanese government announced that the new runway would be shorter, but according to King, the new base will be a lot larger.

Robert Hamilton, former company commander of Okinawa Marine Corps has written articles for the Marine Corps Gazette. In one of these, he argued that the Futenma replacement issue had nothing to do with security policies. The Japanese steel industry has been in stagnation. The top steel manufacturer Nippon Steel has been surpassed by a Korean firm. So the industry needs stimulus. Then Prime Minister Hashimoto endorsed a plan to build a base by placing tens of thousands of steel pilings on the ocean bed, put steel boxes on top of them, connect those boxes, and put hot steel plates to build a runway. According to Hamilton, this was designed to boost the Japanese economy, it was not based on the nation’s security needs.

Artist’s Conception of a Pile-Supported Sea-Based Facility (GAO, March 1998)

Hamilton is an engineer. He knows technical requirements. He says that specific kinds of rings are necessary to connect those steel boxes, and that the technology has not yet been completely developed. The technology is most advanced in the Scandinavian countries, and the U.S. Navy has invested 200 million dollars there in research and development of the rings. The kind of rings presently available are too weak to withstand the strong winds of Okinawa.

Hamilton sent me another article, in which he writes about the 1997 Nago plebiscite (on acceptance of a new base) and Japan’s Defense Agency’s efforts to buy votes by visiting each household, going door to door, delivering alcohol and money. He warned us in the last Nago mayoral election (January 2010) of such activities being repeated, and advised us to stop early-voting, as companies would mobilize their employees to go to the polls and pressure them to vote for the base. I told him that our anti-base side would also mobilize for early-voting.

Former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage said that the 21st century would be the century of “Mega-floats” (also known as Very Large Floating Structures, or VLFS), and endorsed the idea of a mobile base. Robert Hamilton in the article mentioned above says the idea of “Mega-floats” originally came from a man called Watanabe, in the Japanese steel industry, which works with U.S. military-industrial groups such as Bechtel. When I went to the U.S., twenty board members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce wanted to meet with me. Somebody from the military industry proposed a drawing of a new base to me, but I told him I was in the U.S. to oppose base construction. The Japanese steel industry just wants to make anything using steel. It is not a matter of national security; it is a matter of corporate interests.

No need for replacement base – U.S. experts

(Showing thick files), we have collected so many articles written by military and security experts in the U.S. that support our side that are saying that there is no need for a Futenma replacement base. The Cato Institute even submitted an advisory report to the U.S. Congress that recommended that the U.S. military withdraw from Japan and the two countries sign a new peace and friendship treaty to replace the current Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. I invited Cato Institute’s senior fellow Douglas Bandow and showed him the bases in Okinawa. He was surprised to see the level of military occupation still going on in Okinawa. Immediately after he went back to the U.S., he wrote an article that tells how the U.S. has turned Okinawa into its military colony.14

Many Japanese Diet members are sympathetic to Okinawa, but even they tell me that the concentration of bases in Okinawa is inevitable because of its “geopolitical” position. I talked about the “geopolitical issue” with Gene LaRoque, and that made him laugh. He said he had just come back from Korea. Geopolitically, if North Korea were a real threat, it would make a lot more sense to increase U.S. troops in South Korea. We don’t need more U.S. troops in South Korea since it already has military power far surpassing that of the North and national income many times greater than that of its rival. Furthermore, if North Korea were really a threat, northern Kyushu would be more advantageous, being closer to Korea. Knowing that, many in the Japanese Diet still bring up this “geopolitical issue.” It is clear that their primary motive is refusal to contemplate additional bases in the main Japanese islands, leaving Okinawa to bear the burden.

I am trying to let the Japanese people and its media know about those in the U.S., who rationally and intellectually assess the situation in Okinawa and speak out against the unreasonable and unfair burden of the bases in Okinawa. The mainland media, however, refuse to heed these opinions, and only listen to the so-called “ANPO Mafia,” or “Japan Handlers,” like Joseph Nye, Kurt Campbell, and Michael Green. The Japanese media, such as Kyodo, Asahi, and Mainichi, only listen to those people, and ignore the articles and opinions that I bring to their attention. Or, if they do write about them, their bosses in Tokyo suppress the information. They say they need bases in Japan for “deterrence,” but none of the articles that I mentioned or the U.S. experts whom I have spoken to refer to Marines in Okinawa as a “deterrent force.” The true situations of Okinawa must be told in English, to the world. Then we would gain greater understanding and support.

Another issue is the U.S. plan to move Okinawa Marines to Guam. In May 2006, the governments of the U.S. and Japan issued the “United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation.” A few months later, the U.S. Pacific Command released the “Guam Integrated Military Development Plan,”15 and in November 2009, the U.S. publicized an 11,000-page environmental impact statement on Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.16 As Iha Yoichi, Ginowan Mayor and a candidate in the gubernatorial election, points out, the statement indicates that the Marine units stationed in Futenma Air Station are to be transferred to Guam, including their helicopter unit. This would make the construction of a new base in Henoko totally unnecessary. I keep telling the Japanese media about these documents, but they almost never take up the issue. It is deeply disappointing that even Kyodo ignores it. Mainichi and Asahi too. They write a lot about Okinawan resistance, but say nothing about this.

Division at the 30th parallel: truths of the military colonization of Okinawa

I was interested to learn that only six months after the onset of the Pacific War in December 1941, the Departments of Defense and State had already started discussing dividing Japan at the 30th parallel north, with Amami and Okinawa islands south of the parallel, and the rest of Japan north of it. Why did they want to chop off Okinawa and Amami? That was my biggest question for a long time. Despite the joint international research efforts, which I was part of, none of us could find an answer. Amami was part of Kagoshima Prefecture, not of Okinawa. Finally, after five years, we found it.

Then Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson testified in the U.S. Congress that they made that decision because the 30th parallel north was the border between the “Yamato(Japanese) race” and the “Ryukyu (Okinawa) race.” It was a racial distinction. They drew that line because the Ryukyuan people on those islands were not inherently Japanese, and they included Amami, which was technically part of Kagoshima Prefecture, because the islands had once been part of the Ryukyu Kingdom. They also wanted to maximize the occupied area to include more than just Okinawa Prefecture.

Ryukyu Islands and 30th Parallel North

Linguists say that the 30th parallel is the border between the Yamato (Japanese) language and Okinawa language. Biologist Watarase says the ecological systems are different north and south of that parallel too. Similarly, the Korean Peninsula was divided at the 38th parallel. A zainichi Korean author (Korean resident in Japan) says Japanese people are so blissfully ignorant, in thinking they are fortunate, as Japan was not divided after its defeat in the war as Korea was. But it was the Japanese military that first divided Korea. It decided that the elite Kwantung Army would defend north of the 38th parallel, and other armies dispatched from Japan would defend south of the parallel. So, what did the 30th parallel mean militarily for the U.S.? South of it were the Nansei (Southwest) Islands, defended during the war by the Okinawa Defense Army. North of the parallel was “pure Japan,” which was defended by the “Mainland Defense Army.”

So why was Okinawa cut off from Japan? The idea goes back to the late 19th century. The Meiji government abolished the feudal han system and established the centralized ken (prefecture) system in 1871. This was applied to Okinawa in 1879, eight years later, making Okinawa a prefecture of Japan. Historian George H. Kerr wrote a longtime seller “The History of an Island People,” which was translated into Japanese and published in 1956 under the title “Ryukyu no rekishi (History of Ryukyu).” Kerr renounced the Japanese edition because the commander of the U.S. military government took advantage of the book to justify detaching Okinawa from Japan.

Kerr argues that the policy applied to Okinawa was completely different from that applied to the mainland. Other prefectures were created on the assumption of shared culture, language, and ethnicity, with the goal of creating a modern, centralized nation state. But the incorporation of Okinawa had a fundamentally different logic. The Meiji government wanted Okinawa to be a southern shield for the defense of the mainland, with permanent presence of military forces there. They wanted the Okinawan lands; not the Okinawan people. Okinawans fiercely opposed government plans to station the Kumamoto 6th Division there. The Meiji government eventually used force to make Okinawa obey. This is why the process of incorporation was called the “Ryukyu Disposition,” something unheard of in the creation of other prefectures.

U.S. post-war occupation policy focussed on demilitarization and disarmament of Japan. Part of this demilitarization process involved detaching Okinawa, because the southernmost islands had been used by Japan as a base for the invasion of other Asian countries. The U.S. used Okinawa as collateral for Japan’s disarmament.

When Japan surrendered, the Allied Powers entered a defeated nation that still had 4.4 million troops with a force of only 300,000 to 400,000. Fearing an uprising, Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, decided to reinforce U.S. troops in Okinawa. Those U.S. forces in Okinawa would be “the cap in the bottle,” acting as a deterrent to prevent uprising of the remaining Japanese troops, or future military build-up of Japan. MacArthur, with the understanding that Okinawans were not Japanese, expected that any form of liberation from Japanese oppression would please Okinawans, whether it was militarization of the whole island or detachment from the Japanese nation. He also thought that Japan would have no use for resource-poor Okinawa.

Up until 1968, there was no democratic system for Okinawan people to choose their leader. Under U.S. occupation, Chief Executives of the Ryukyu Government were appointed by USCAR (U.S. Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands), with the influence of the U.S. military commander. With Okinawan people’s movement, however, the first popular election was finally held in 1968, and the progressive candidate Yara Chobyo won.

Yara Chobyo, Okinawa’s first elected governor

We now know that Edwin O. Reischauer, who was the U.S. Ambassador to Japan from 1961 to 1966, tried to increase the number of pro-occupation representatives within Okinawa’s Legislature with CIA funding, intending to crush the progressive forces. The U.S. and Japanese governments threw in 720,000 dollars and 880,000 dollars respectively, into their attempt to influence the election, but they failed with the victory of Yara Chobyo. This is how Okinawa’s hard-earned democracy has been manipulated. We got all this information from declassified documents in the U.S. Archives. I cannot stress enough the importance of these documents, and the need for continued efforts to obtain more.

Making Friends beyond the Wall

Why is it so hard to solve Okinawa’s problems? In democracy, the majority wins by definition. Among the 772 members of the Japanese Parliament, only 9 represent Okinawa. Mainland politicians don’t think about Okinawa’s military base issue as their own problem, because doing that would not help them gain votes in their constituency. Okinawa has always been discriminated against, because of this majoritarian principle. So how can we address this challenge?

I asked Danilo Dolci, who received the Lenin Peace Prize for leadership in the non-violence movement, what he would do if he were Okinawa’s Governor to overcome that “thick wall” between Okinawa and the enormous powers of the U.S. and Japanese governments. Dolci said, “Government power is hard to undermine. You can’t fight them head-on. If you feel that you are stuck against the ‘thick wall,’ make friends on the other side of the wall. That way, the ‘wall’ will cease to exist.” Understandably as a trade union leader, he also said, “Trust common people.” Interestingly, Johan Galtung, founder of the International Peace Research Institute in Norway, and Rajmohan Gandhi, grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, said the same thing when they came to Okinawa.

When I studied journalism in the U.S., I was told that common people were like a flock of birds… just flying together wherever the wind blows. But these three influential people – Galtung, Dolci, and Gandhi all said the same thing: trust the common people. I was impressed. I met Dolci right before the Berlin Wall collapsed. People in East and West Germany still visited each other despite the Wall. Then the wall became virtually non-existent. I was fascinated with Dolci’s foresight. This is why I make as many friends as possible whenever I am overseas. (Showing a file) Here we have over 600 articles supportive of Okinawa. We have also received about 220,000 letters of support from the U.S., Japan, China, Singapore, and beyond.

I also see that an increasing number of young researchers abroad are specializing in Okinawa. Here at our office, we have collected more than 300 MA and Ph.D. dissertations on Okinawa. I met one young British man who is studying the 700 year history of Kin Town, and a British woman who is studying the life of the last king of the Ryukyus, Sho Tai. Three PhD’s have been awarded in London for study of the sanshin, Okinawa’s “three-string” musical instrument. When a Georgian Ph.D. student came to see me, I asked her why she was studying Okinawa. She said it was because there were so many Okinawas in the world; in other words, because minority societies are always oppressed. Learning about Okinawa helped her understand her own country, Georgia, also under constant pressure from Russia.

The world is beginning to know what is going on in Okinawa, and I hope such international exchange of friendship and scholarship between Okinawa and the rest of the world will help dissolve the “wall.”

Ota Masahide, former Governor of Okinawa (1990-1998), former Member of the Japanese House of Councillors (2001-2007), is a professor emeritus at the University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa and Director of the Ota Peace Research Institute. He was born in Okinawa in 1925. While a student at Okinawa Teacher’s College, he was drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army as a member of Tekketsu Kinnoutai (Blood and Iron Corps), organized just before the invasion of Okinawa by U.S. forces on April 1, 1945. After the war, he went to Tokyo to attend Waseda University, graduating in 1954. He went to the United States as a scholarship student, receiving an MA degree in journalism from Syracuse University in 1956. He has taught at the East-West Center, University of Hawaii (1973) and was a Fulbright visiting scholar at Arizona State University (1978). He has written more than eighty books on Okinawa, including The Battle of Okinawa, Essays on Okinawa Problems, The Okinawan Mind (Okinawa no Kokoro), Who Are the Okinawans? (Okinawajin towa Nanika), The Political Structure of Modern Okinawa (Okinawa no Seiji Kozo), and The Consciousness of the Okinawan People (Okinawa no Minshu Ishiki), among others.

Satoko Norimatsu, an Asia-Pacific Journal editor, is Director of the Peace Philosophy Centre, a peace-education centre in Vancouver, Canada, and Director of Vancouver Save Article 9. She leads youth and community members in promoting and learning about Article 9, historical reconciliation in Asia, Hiroshima/Nagasaki and nuclear disarmament, and issues surrounding U.S. military bases in Okinawa.

Recommended citation: Satoko Norimatsu, “‘The World is beginning to know Okinawa’: Ota Masahide Reflects on his Life from the Battle of Okinawa to the Struggle for Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 38-4-10, September 20, 2010.

Articles on related themes:

Gavan McCormack, The US-Japan ‘Alliance’, Okinawa, and Three Looming Elections

Ryukyu Asahi Broadcasting and Norimatsu Satoko, Assault on the Sea: A 50-Year U.S. Plan to Build a Military Port on Oura Bay, Okinawa

Kensei Yoshida, Okinawa and Guam: In the Shadow of U.S. and Japanese “Global Defense Posture”

Makishi Yoshikazu, US Dream Come True? The New Henoko Sea Base and Okinawan Resistance

Ahagon Shoko and C. Douglas Lummis, I Lost My Only Son in the War: Prelude to the Okinawan Anti-Base Movement

Yoshio Shimoji, The Futenma Base and the U.S.-Japan Controversy: an Okinawan perspective

Iha Yoichi, Why Build a New Base on Okinawa When the Marines are Relocating to Guam?: Okinawa Mayor Challenges Japan and the US

Notes

1 Ota Peace Research Institute, Okinawa kanren shiryo – Okinawa sen oyobi kichi mondai, 2010, p.2

2 ibid.

3 ibid.

4 The morning edition of Ryukyu Shimpo on July 19, 1969 reported that The Wall Street Journal reported the incident in its July 18, 1969 edition. “11 Beigun no dokugasu haibi hakkaku 1969 nen 7 gatsu 19 nichi chokan,” Ryukyu Shimpo, July 24, 2009. Link.

5 Some details of “Operation Red Hat” are available at “Dokugasu iso hajimaru,” January 13, 2009 entry of the blog of Okinawa Prefectural Archives. Link.

6 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, The SACO (Special Action Committee on Okinawa) Final Report, December 2, 1996. Link.

7 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Security Consultative Committee Document, U.S.-Japan Alliance: Transformation and Realignment for the Future, October 29, 2005. Link.

8 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, United States – Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation, May 1, 2006. Link.

9 Department of Defense, Operational Requirements and Concept of Operations for MCAS Futenma Relocation, Okinawa, Japan, Final Draft, September 29,1997

10 United States General Accounting Office, Overseas Presence, Issues Involved In Reducing the Impact of U.S. Military Presence on Okinawa, March 2, 1998. Link.

11 “Marines’ move to Guam to cost more,” The Japan Times, July 4, 2010. Link.

12 Photo courtesy Ginowan City website. Accessed September 24, 2010. Link.

13 NHK News, broadcast on April 10, 1998

14 Douglas Bandow, “Okinawa: Liberating Washington’s East Asian Military Colony.” September 1, 1998. Link.

15 U.S. Pacific Command, Guam Integrated Military Development Plan, July 11, 2006 (The document is downloadable here).

16 U.S. Department of the Navy, Guam and CNMI Military Relocation – Environmental Impact Statement, November 2009. Link.