China’s Port Development and Shipping Competition in East Asia

By Nazery Khalid

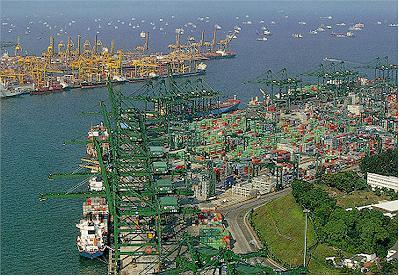

[China and East Asia are experiencing a harbour construction boom as the region gains a position of ascendance in global trade. Nazery Khalid – Research Fellow, Center for Economic Studies and Ocean Industries. Maritime Institute of Malaysia – reports that 7 of the world’s 20 busiest terminals are in China. The port to watch is Shanghai, which is poised to overtake its main rivals (Hong Kong and Singapore). In 2005, Shanghai handled 443 million tons of cargo in total and 18.09 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of containers, an increase of 24.2 percent compared with the previous year (Hong Kong handled 23.2 million TEUs and Singapore 22.43 TEUs). The Shanghai region is expected to handle 35 million TEUs of container traffic by 2010. This is because the port of Ningbo will continue its own frenetic expansion of capacity as well as install the world’s longest bridge (the US$ 1.4 billion Hangzhou Bay Bridge) to cut the travel time to Shanghai to two hours. In addition, Shanghai is adding a deepwater facility in nearby Yangshan and working out deals with other North China ports to provide international service for them.

Clearly at work in the above example are the economies of scale in the midst of massive growth. Development in China is also clustering in defined areas, which further enhances efficiencies through the phenomenon of agglomeration economies (e.g. the efficiencies gained by firms being in close proximity). The result is that exports and fixed investments in China are expanding at a combined rate of 25 percent per year, according to Morgan Stanley’s latest data.

One of the implications of that macro-economic statistic and China’s cost advantages is that ports elsewhere in the Asian region face a ferocious competitive challenge. Seven of the world’s other busiest terminals are in non-China Asia, so the juggernaut in their collective neighbourhood is not merely something to marvel at from afar. For example, the South Koreans are worried about the competition. The port of Busan (11.84 million TEUs in 2005), the 5th largest in the world, plans to roughly double its existing capacity by 2011. But with studies suggesting that Shanghai’s overall expansion could capture nearly a third of Busan’s business, the Koreans are frantically emphasizing efficiency and competitive pricing in their projections.

For its part, Singapore has adopted a strategy of trying to maintain its position by cooperating with China’s rapidly growing ports. Singapore’s port authority emphasizes business opportunities through providing specialized services in port operations as well as in building strategic alliances. Whether this kind of strategy works over the long term remains to be seen. But it is further evidence that the “China factor” – as Khalid refers to the country’s mushrooming presence – is something all countries in the region are compelled to confront even as intra-Asian trade spirals. AD]

No discussion of China’s tour de force economic performance is complete without taking a look at its maritime strengths and port development, as a majority of its international trade is carried by way of sea. China has been ranked as the world’s third largest trading country (U.S.-China Business Council Report, November 20, 2005), and fourth most important maritime state by way of number of merchant fleet and its 6.77% contribution to the world’s total tonnage (UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport, 2005). At the end of 2004, it commanded a 6.2% share of world trade generated in terms of value (Ibid.)

The explosion in its international trade has had a tremendous impact on the growth of its port sector and has excited China’s planners to hurriedly continue expanding its port capacity to support trade and container traffic growth. This has become a matter of national interest, as the coming years promise to see China sustaining strong trade performance. This is expected to boost its cargo base, especially from the manufacturing sector, and demand more of its port and shipping and services.

The Chinese government is giving top priority to develop its ports under its 11th Five Year Plan to support the country’s breakneck economic growth. The plan lays down a systematic strategy to develop its ports, and a huge amount of funds have been allocated for this purpose.

Today, as a result of the economic boom across Asia, no doubt galvanized by escalating trade with China, 14 of the world’s top 20 container terminals are Asian-based (UNCTAD, 2005). An amazing seven of these terminals are located in China, underlining the rapid growth of its trade and economy and its growing clout as a maritime power (Ibid.).

Main Chinese ports have grown tremendously to be listed in the above ranking of the world’s top 20 terminals, displacing ports like Kobe and Yokohama. Their growth rates have also far outstripped other more established Asian ports. For example, Hong Kong, the world’s busiest port since 1992, has been growing at a lower rate compared to Shanghai and Shenzhen ports, which have experienced increased throughput by more than threefold from 1999 to 2004.

Leading the explosion of growth of Chinese ports is Ningbo Port, which notched the highest percentage gain in 2004. The port has been growing at an astounding average growth in TEU [1] traffic rate of 44% for the last six years (China Business Review, 2005). Shanghai port is projected to be the biggest hub port in East Asia and to serve as China’s distribution and logistics services base for global trade. The concentration of cargo base and increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) has resulted in Shanghai outpacing other areas growth in the country. It is expected to handle a capacity of 25 million TEUs by 2010, double the volume handled in 2004 (China Daily, February 25, 2004).

Besides container ports, other types of terminals are also being commissioned to facilitate China’s emerging energy needs and growing demands for bulk commodities like iron ore and grains. The largest Chinese facility to unload Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) vessels is being constructed in Dalian, equipped to serve six refineries with a total capacity of 46 million tons (UNCTAD, 2005).

The formation of economic clusters of regions has also contributed to the development of Chinese ports. The economic regions include Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei circle, the west region, central China region and northeast industrial region.

As more manufacturing industries move from the south to the eastern and northern region of China, infrastructure development in this region has intensified. With the concentration of manufacturing activities in the Yangtze River corridor, the need for China to improve the connectivity between central China and its coastal ports becomes more critical. With the opening of Three Gorges Dam (supposedly in 2009), container movement is expected to intensify in the area. River transportation and river ports are also given priority in infrastructure development to meet China’s growing trade.

The booming Chinese economy has led to increasing container volumes going in and out of China, resulting in the increase of feedering services. Feeder lines are bringing in more cargo from industrial centers and small, less accessible ports along the Yangtze River to main ports, where the cargo is consolidated for loading on mainline carriers. This is underlined by the construction of the 3-million TEU capacity Yangshan Port aimed at facilitating spare capacity for the predicted traffic growth in the Yangtze River Delta (UNCTAD, 2005).

China and Southeast Asia

Reflecting ever-growing inter-regional trade, containerized trade between China and Southeast Asian countries is expected to grow across the board this year. In 2004, bilateral trade volume between reached US$105.9 billion and, according to state media, soared to US$130.4 billion in 2005, a 23 percent increase. Yi Xiaozhun, a Commerce Ministry Vice Minister said ASEAN became the fifth largest export market for China and the fourth largest source for imports in 2005, partly due to tariff reductions on approximately 7,000 categories of goods. Chinese President Hu Jintao is bullish regarding trade with the region, setting a $200 billion target by 2010 during a visit to Southeast Asia last April. This bodes well for port throughput and port development in the region. Regional ports such as Singapore, Port Klang and Tanjung Pelepas have benefited tremendously from the flourishing Chinese economy, recording substantial growth in throughput, and will continue to enjoy the patronage of Chinese trade.

Chinese ports have also engaged in strategic alliances with foreign port management companies. The port of Dalian has entered into a strategic partnership with APM Terminals, Cosco Pacific and Port of Singapore Authority to develop the port to serve the northern regions of China. Xiamen Port Authority has also signed an agreement with APM Terminals to finance the development of a new three-berth terminal estimated to cost US$350 million. These engagements underline the ambition of Chinese ports to grow in line with the explosive trade growth in the country.

A good example is Singapore’s foray into China, via PSA International’s operations in the ports of namely in Dalian, Fuzhou and Guangzhou. Its involvement in these ports has enhanced their cost of service, value for money, average speed to berthing, onsite facilities, turnaround time, frequency of liner calls and overall efficiency and management. Underlining the positive impacts of this strategic alliance, PSA China secured Best Emerging Container Terminal award for Guangzhou Container Terminal at the Lloyd’s List Maritime Asia Awards in 2004.

In addition to PSA’s initiative, Maritime Port Authority of Singapore has been at the forefront of capturing business from growth markets such as China via strategic alliances. In May 2004, Singapore and China signed an MOU on Maritime Cooperation, paving the way for cooperation in areas such as port management and development, shipping, training and R&D. The two countries also signed a protocol to allow their shipping companies to set up wholly-owned subsidiaries on each other’s turf without any geographical hindrances.

Energized by strong performance in trade with China, ports in the ASEAN region have also expanded and improved not only in terms of infrastructure and sophisticated equipment but also in the functions and business activities. Many have added and improved value added logistics and ancillary services to gain a competitive edge to attract cargo from and to facilitate export to China. With ever-increasing international maritime container cargo movement in and out of China and the deployment of ever-larger container ships to accommodate this, several key hub ports in the region have upgraded their facilities, even building new ones.

An example is the new port city in Zhangjiagang which, in the last few decades, has seen tremendous development around its port. The port acts as a multifunctional trade harbor servicing the city and industries along the Yangtze River. Part of the larger Suzhou Port organization that includes Changshu and Kundhan, Zhangjiagang Port has 40 berths with 10,000-ton-class capability and handles 40 million tons annually (UNCTAD, 2005). If it meets the expectation of being able to handle 1 million TEU or equivalent to 100 million by 2010, it will become the first port to reach that capacity in the Jiangsu Province (Asia Pacific Shipping, August 2005).

The influence of the “China factor” on the development of ports—a crucial facilitator of international trade—has been momentous and looks set to color the ports scene in the years ahead. Although the consequence of the impact may not be applicable to all the ports in the SEA region, some are notable for their magnitude and for mirroring global trends in port development. They include advances in shipping technology and practices, concentration of resources and processes, and door-to-door delivery stretching across the supply chain [2]. Larger ships with better technologies are being built, requiring ports that are able to match their features with the capacity and skills to facilitate their calling. The spate of mergers and alliances among shipping economies to achieve economies of scale will continue to push the envelope for ports to enhance their infrastructure and manpower to cater to bigger ships with more loads. Just-in-time production and the increasing pressure to deliver more goods at lower cost and shorter time to wider market areas have spurred the development of multimodal transport, facilitating the seamless movement of goods across the various transport modes. These have been critical to the planning, organization, development, management and operation of seaports in the region.

Challenges for ASEAN

Challenges abound for port planners in the Southeast Asian region to plan their port development, enhance infrastructure, keep updated with state-of-the-art technologies, increase productivity, organize operations efficiently, invest wisely and allocate resources effectively to cater to greater Chinese maritime trade volume. In light of the growing trade between the ASEAN region and China, and the projected growth boosted by the FTA between the two, regional ports keen to capitalize on growing cargo volume should enhance their capacity and competitiveness to attract mainline operators and process ever-growing throughput.

Notes

- Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit (TEU) is the standard measure of counting containers. 2. Nazery Khalid, “The Impact of Cargo Trends on Terminal Developments in Asia.” Paper presented at the 3rd ASEAN Ports and Shipping Conference 2005, Surabaya, September 22, 2005 (http://www.mima.gov.my/mima/htmls/papers/pdf/nazery/surabaya.pdf).

Nazery Khalid is a Research Fellow at the Maritime Institute of Malaysia. This article appeared in China Brief, March 29, 2006. Posted on Japan Focus April 8, 2006