Zia Mian and M. V. Ramana

As the current Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh risks his administration on a bid to override massive public opposition to entering into a nuclear power deal with the United States, hyped as an “historic” accord that will emancipate India’s economy and boost its international status, Japan Focus examines a decade of India-Pakistan maneuvering for advantage in the South Asian nuclear sweepstakes. MS

We in America are living among madmen. Madmen govern our affairs in the name of order and security. The chief madmen claim the titles of general, admiral, senator, scientist, administrator, secretary of state, even president. . . . Soberly, day after day, the madmen continue to go through the undeviating motions of madness: motions so stereotyped, so commonplace, that they seem the normal motions of normal men, not the mass compulsions of people bent on total death. Without a public mandate of any kind, the madmen have taken it upon themselves to lead us by gradual stages to that final act of madness which will corrupt the face of the earth.

Lewis Mumford (1946), in response to the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the announcement of additional nuclear weapons tests.

The tenth anniversaries of the May 1998 Indian and Pakistani nuclear weapons tests were muted in both countries. Neither staged official ceremonies to commemorate the tests, while public events were few and drew little support. India’s Press Information Bureau issued a statement on what it called “National Technology Day,” recalling May 11, 1998, as “the defining moment in the growth of technology prowess,” but making no mention of the nuclear tests.[1] Pakistan’s foreign affairs ministry released a short statement to mark the anniversary, calling them a “historic day in the nation’s quest for security.”[2] It was all a far cry from both countries’ official exultation and public jubilation at the time of the tests.

This article reviews nuclear weapons related developments in south Asia since 1998. We start by looking briefly at diplomatic efforts to manage nuclear dangers, the role of nuclear weapons in India-Pakistan crises after the tests, and the subsequent planning and preparations for fighting a nuclear war. We describe the developments in the nuclear weapons command structures, the testing and deployment of missiles to carry these weapons, and the current status of the production of fissile materials (plutonium and highly enriched uranium) for nuclear weapons.

Nuclear Denial

One striking feature of years since the May 1998 nuclear tests is the growing disconnect between nuclear realities and the two countries’ ongoing peace process. Leaders in both nations behave as if the bomb they nurture is marginal to the peace process they claim to be taking forward, even though the nuclear weapons policies they promote at home are geared toward destroying the other country.

The trend started at the February 1999 Lahore meeting between Indian prime minister A. B. Vajpayee and Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif. While the Lahore Declaration promised “immediate steps for reducing the risk of accidental or un authorised use of nuclear weapons” and “measures for confidence building in the nuclear and conventional fields, aimed at prevention of conflict,” the actual commitments by the two countries amounted to very limited transparency measures (Mian and Ramana 1999). Subsequent talks went no further and offered steps that were insignificant in the face of the nuclear crises that the two countries had gone through and the arms race underway between them (Mian et al. 2001; Mian, Nayyar and Ramana 2004).

The continued unwillingness to grapple with the bomb was revealed most recently in the May 2008 meeting of the India’s and Pikistan’s foreign ministers in Islamabad. Their joint statement said “the talks were held in a friendly and constructive atmosphere” and that they “resolved to carry forward the peace process and to maintain its momentum.”[3] The ministers noted “a number of important bilateral achievements,” including a memorandum of understanding to allow more air travel between the two countries, an agreement for trucks to cross at the Wagah-Attari border, and an accord to allow the Delhi-Lahore bus to make one additional weekly trip. The 2007 agreement on “Reducing the Risk from Accidents Relating to Nuclear Weapons” only made number four on the list of achievements.

But this is to be expected. Almost 10 years after nuclear talks commenced, all there is to show are an agreement to inform each other about missile tests and a nuclear hotline in case of accidents. This suggests a failure of both imagination and political will to seriously engage with the nuclear danger. The peace process does not seem to recognise that since 1998, there has been a war and a major military crisis, both prominently featuring nuclear threats (Ramana and Mian 2003).

Nuclear denial in South Asia is not a symptom of inattention, or passivity in the face of an overwhelming problem. It is deliberate blindness to the contradiction between word and deed. Pakistan and India talk of peace while pouring scarce resources into developing their nuclear arsenals, the infrastructure for producing and using them, and doctrines aimed at fighting nuclear war. As the two states lay the technical and organisational basis for what was aptly labelled during the superpower cold war as Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), the foreign ministers’ joint statement could only manage to agree that “The Expert Groups on Nuclear and Conventional CBMs [confidence building measures] should consider existing and additional proposals by both sides with a view to developing further confidence building measures in the nuclear and conventional fields.”

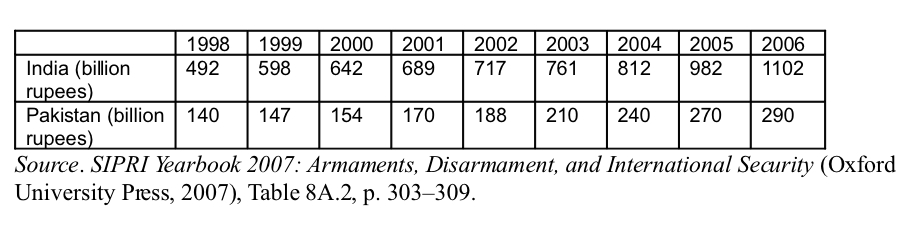

The nuclear arms race is part of a larger military buildup since the tests. Contrary to nuclear weapons advocates’ claims that building nuclear weapons reduce conventional military expenditures,[4] actual figures for both countries show significant and consistent increases (see table 1). In both countries, spending on nuclear weapons programs is spread across various departments and is not publicly accounted for.

Table 1: Military Expenditure in India and Pakistan, 1998–2005 (Local Currency, Current Prices for Calendar Years).

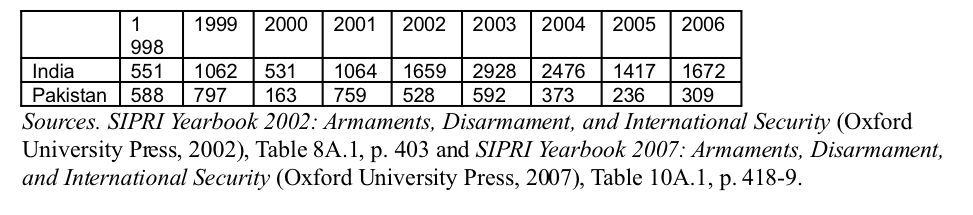

Lacking the capacity to build many major conventional weapons systems for themselves, the two countries have been investing heavily in importing arms from various countries. Table 2 indicates the amount of money India and Pakistan have spent between 1998 and 2006. Much more is in the pipeline. A September 2007 U.S. Congressional Research Service report noted that in 2006, Pakistan was ranked first among third-world countries in terms of the value of arms purchase agreements, having signed $5.1-billion worth of such agreements. India was ranked second with $3.5-billion worth of arms purchase agreements (Grimmett 2007).

Table 2: Indian and Pakistani Arms Imports, 1998–2006 (in Millions of U.S.$ at Constant 1990 Prices)

The high levels of military expenditure and arms purchases go hand-in-hand with widespread poverty and misery in both countries, and a continued reliance, especially in Pakistan, on international development aid to help provide basic services such as healthcare and education.

Crossing Nuclear thresholds

Nuclear weapons advocates have always promised that nuclear weapons would prevent war, if not bring peace. The simple argument was that fearing destruction by the other side’s nuclear weapons, no country would risk war. Within a year of the tests, however, India and Pakistan went to war in the Kargil region of Kashmir. Although geographically limited, the war claimed perhaps several thousand lives.

Air strikes were mounted for the first time since the 1971 war. Nuclear weapons served to encourage senior Indian and Pakistani officials to issue nuclear threats; by one reckoning, at least 13 indirect and direct nuclear threats were made (Bidwai and Vanaik 1999, vii). The crisis was not resolved by nuclear threats or mutual diplomacy. Pakistan sought American intervention to stop the fighting and to help resolve the Kashmir dispute. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is described as becoming “desperate” in his appeals for help and flew to Washington to meet with U.S. president Bill Clinton (Riedel 2002). Clinton refused to become involved unless Pakistan withdrew its forces from Kargil without preconditions, and confronted Sharif with the information that the Pakistani army had mobilized its nuclear-tipped missiles. Sharif reportedly seemed “taken aback” when confronted with this fact, and argued that India was likely to be doing the same, but denied having given the order to arm Pakistan’s missiles. Failing to get support from the U.S. for a face-saving end to the fighting, Pakistan agreed to an immediate withdrawal.

A December 2001 militant attack on the parliament building in Delhi triggered another crisis. Over half a million troops, about two-thirds of them Indian, were moved to the Pakistani border. Senior officials and politicians in both countries invoked nuclear weapons on several occasions. Prime Minister Vajpayee warned: “no weapon would be spared in self-defence. Whatever weapon was available, it would be used no matter how it wounded the enemy” (Shukla 2002). Many around the world rightly feared the worst.

The 1999 and 2001–02 military confrontations offer important lessons. The first lesson is that, having nuclear weapons at hand, leaders in both India and Pakistan are willing to use them to make threats during a crisis to try to force a resolution on their own terms and to incite international attention and intervention. This is a way to use nuclear weapons without detonating them. As Daniel Ellsberg pointed out, “a gun is used when you point it at someone’s head in a direct confrontation, whether or not the trigger is pulled” (Ellsberg 1981).

Kargil also showed that nuclear weapons have changed the calculus of risk for generals and policymakers. The late Benazir Bhutto revealed that in 1996, Pakistani generals had presented plans for a Kargil-style operation, which she vetoed (Anonymous 2000). It would seem that the 1998 tests convinced Pakistan’s leaders that the operation might be feasible with nuclear weapons to restrict any possibly decisive Indian riposte. The Kargil war was seen in very different ways by two countries’ leaders. For Pakistan, Kargil represented proof that its nuclear weapons would prevent India from launching a massive military attack. For India, Kargil meant that it would have to find ways of waging limited war that would not lead to the eventual use of nuclear weapons. Although it did not develop into war, a number of factors make the 2001–02 crisis a more dangerous portent for the future than the Kargil war. Unlike Kargil, where Pakistan clearly lost, especially politically, both sides claimed victory in 2002. Some in India see President Pervez Musharraf’s promise that he would rein in Pakistan-based militant organisations as proof that Indian “coercive diplomacy” worked despite Pakistan having nuclear weapons. In Pakistan, some see nuclear weapons having deterred India from crossing the border, despite its huge buildup of forces and threats to attack militant camps in Pakistan. That a massive military confrontation with strong nuclear overtones is seen by both sides as a victory increases the likelihood that similar incidents will occur in the future.

While Pakistan’s leaders stress their nuclear weapons’ utility in 1999 and 2001–02, Indian leaders have made a point of denying a role for such threats. Prime Minister Vajpayee claimed that the 2001-02 crisis showed that India had successfully called Pakistan’s nuclear bluff (Vanaik 2002). General V. P. Malik, former chief of army staff, stated that nuclear weapons were largely irrelevant and played no deterrent role during the Kargil war or the 2002 crisis. This position was echoed by other senior Indian military officials (Mehta 2003). Responding to Pakistan’s strategy of using nuclear threats to incite international intervention, in 2004 the Indian army adopted a new and dangerous war doctrine called “Cold Start” — which aims to give India the ability to “shift from defensive to offensive operations at the very outset of a conflict, relying on the element of surprise and not giving Pakistan any time to bring diplomatic leverages into play vis-a-vis India” (Pant 2007). The offensive operations would involve a very quick, decisive attack across the border with Pakistan and, some analysts argue, to “bring about a favourable war termination, a favourite scenario being to cut Pakistan into two at its midriff” (Ahmed 2004). The strike is meant to be so swift and decisive that it would “preempt a nuclear retaliation” (IE 2006).

India carried out a trial version of this tactic in May 2006 with a major military exercise close to the Pakistani border (ToI 2006). The sanghe shakti (joint power) exercise brought together strike aircraft, tanks, and more than 40,000 soldiers from the Second Strike Corps in a war game whose purpose an Indian commander described as “test[ing] our 2004 war doctrine to dismember a not-so-friendly nation effectively and at the shortest possible time” (DN 2006). General Daulat Shekhawat, commander of the corps explained that “We firmly believe that there is room for a swift strike even in case of a nuclear attack, and it is to validate this doctrine that we conducted this operation” (IANS 2006).

Such a policy’s danger is that Pakistani generals are likely to adopt policies that involve using their nuclear weapons early in the conflict, rather than lose both the weapons and the war. And sure enough, for their part, Pakistani military planners have been publicly laying out various “red lines” that might result in their use of nuclear weapons. General Khalid Kidwai, Pakistani Army Strategic Plans Division director, has explained that Pakistan might be forced to use nuclear weapons if: (1) India attacks Pakistan and takes a large part of its territory; (2) India destroys a large part of Pakistan’s armed forces; (3) India imposes an economic blockade or limits access to river waters; or (4) India creates political instability or large-scale internal subversion in Pakistan (Martellini and Cotta-Ramusino 2002).

The two military plans carry are potentially catastrophic if they encounter each other on the battlefield. Indian generals may hope for, and promise their leaders, a decisive but limited attack that will not trigger Pakistan’s use of nuclear weapons.[5] But in any crisis, inadvertent or deliberate escalation is always a risk. Nuclear thresholds might well be crossed without anyone actually intending to, by mistake, by one side misunderstanding what the other is planning and doing, or in the heat of the moment. The Kargil war offers examples. In Pakistan, Sharif did not know what his generals were doing. In India, concerns about escalation gave way to a perceived need to prevail as the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) recommended against using airpower, fearing that it would enlarge the scope of the conflict, only to reconsider its decision and give the go-ahead after a week of ground fighting brought no gains (Ganguly and Hagerty 2005, 154).

Planning Mass Destruction

All nuclear-armed states learn quickly that having the bomb and the will to threaten to use it are not enough. It only functions as a threat when the adversary believes it can be used as intended. It must take on all the attributes of a weapon. Since 1998, India and Pakistan have set up formal organisational structures to plan and manage their use of nuclear weapons.

India

Some months after ordering the nuclear tests, India’s Bharatiya Janata Party government set up a National Security Council, which included a National Security Advisory Board (NSAB).[6] In August 1999, the NSAB released its draft report on a nuclear doctrine (DND) for India (NSAB 1999). In January 2003, the Indian government’s cabinet committee on national security published a brief official statement on the nuclear doctrine (PMO 2003). The relationship between the two has been elucidated by the first convenor of the NSAB, who argued that the latter document shows that “the cabinet committee on national security has . . . accepted the draft nuclear doctrine” (Subrahmanyam 2003). The DND echoes nuclear weapon states’ postures. It declared: “India shall pursue a doctrine of credible minimum nuclear deterrence.” According to the DND, this pursuit requires:

(1) sufficient, survivable and operationally prepared nuclear forces;

(2)a robust command and control system;

(3) effective intelligence and early-warning capabilities;

(4) planning and training for nuclear operations; and

(5) the will to employ nuclear weapons.

These nuclear forces are to be deployed on a triad of delivery vehicles of “aircraft, mobile land-based missiles and sea-based assets” that are structured for “punitive retaliation” so as to “inflict damage unacceptable to the aggressor.” The DND called for an “assured capability to shift from peactime deployment to fully employable forces in the shortest possible time.” The three armed-service headquarters were subsequently reported to be “drawing up detailed schemes for inducting a variety of nuclear armaments and ancillary and support equipment in their orders-of-battle . . . [and] appropriate command and control frameworks” (Karnad 2002, 108).

The Indian government’s formal embrace of a nuclear deterrence doctrine is in marked contrast with previous governments’ public positions. As recently as 1995, at the International Court of Justice (the “World Court”), India’s representative described nuclear deterrence as “abhorrent to human sentiment since it implies that a state if required to defend its own existence will act with pitiless disregard for the consequences to its own and adversary’s people.”

Apart from basic strategic and ethical problems with deterrence, the notion that there is or can be a stable “minimum deterrent” is unfounded. It is not enough to put up a “beware of the nuclear weapons” sign for all to read and take heed. Nuclear history suggests that what seems acceptable to one leadership may seem intolerable to another and may depend on circumstances. In a telling observation, General Thomas Power, U.S. Strategic Air Command head, observed in 1960 that “The closest to one man who would know what the minimum deterrent is would be [Soviet leader] Mr. Khrushchev, and frankly I don’t think he knows from one week to another. He might be able to absorb more punishment next week than he wants to absorb today. Therefore a deterrent is not a concrete or finite amount” (Schwartz 1998).

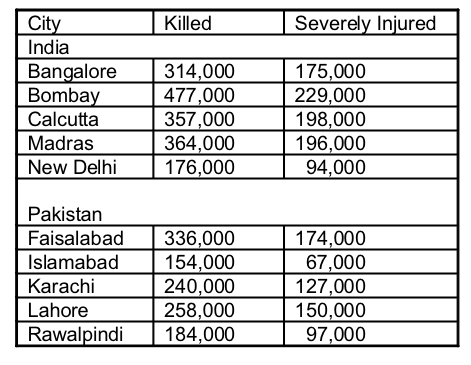

We leave it to the reader to consider how, if given the responsibility, to determine the number of cities he or she would be willing to destroy to produce a deterrent effect in another country’s leadership. Would they consider it sufficient to threaten to destroy Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Karachi, Lahore, and Faisalabad for Pakistan’s generals to be deterred? And, conversely, how many Indian cities would they be willing to see destroyed before they would be deterred — would risking the destruction of Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, and Bangalore be sufficient? Despite government plans, there is no prospect of an effective civil defence against such a nuclear attack (Rajaraman, Mian and Nayyar 2004). Table 3 gives estimates for the casualties that would result from a nuclear attack with just one Hiroshima-sized weapon on each of these cities (McKinzie et al. 2001).

Recognising that the word “minimum” has little or no meaning in the context of nuclear deterrence, it is not surprising that India’s nuclear doctrine documents do not assign a number to the term, minimum. Nor do most nuclear strategists or policymakers.[7] If one were to go by public articles by some of the doctrine’s authors, the planned arsenal could number hundreds of nuclear weapons, and include several different types. The negotiations on the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal suggest that Indian policymakers seem to be interested in having the option to build up stocks of nuclear weapons material to allow for such a large arsenal (Mian et al. 2006).

India’s nuclear doctrine affirms a commitment to no first use (NFU) of nuclear weapons in a conflict. Many aver that this is proof India does not intend to attack anyone with its nuclear weapons, and that its weapons are meant as a defence. However, this may be harder to implement in a crisis than its supporters claim and may not be convincing to others in any case. In a conflict between two nuclear-armed states, a strict NFU policy would entail waiting for the other’s bomb to explode before responding. Experience suggests policymakers may not be planning to do so. In February 2000, responding to threats of a Pakistani nuclear attack, Prime Minister Vajpayee said, “If they think we will wait for them to drop a bomb and face destruction, they are mistaken” (Gardner 2000). Pakistan claims that India’s NFU position is not credible. Pakistan’s ambassador to the United Nations Conference on Disarmament has argued that “India itself places no credibility in ‘no-first-use’. If it did, it should have accepted China’s assurance of ‘no-first-use’ and of non-use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states. This would have obviated the need for India’s nuclear weapons acquisition” (Akram 1999). India has put conditions on its NFU policy in its nuclear doctrine. It expanded the range of circumstances that could draw a nuclear response to include attacks with chemical and biological weapons (CBW). This caveat about CBW attacks may well be the first step to completely repudiating the NFU policy. The 2003 nuclear doctrine statement also included a description of the organisations set up to manage the nuclear and missile arsenals. These were to be under a two-layered structure called the Nuclear Command Authority (NCA), which comprises the political council, chaired by the prime minister, and the executive council, chaired by the national security adviser to the prime minister. The political council is the sole body able to authorise the use of nuclear weapons. However, “arrangements for alternate chains of command for retaliatory nuclear strikes in all eventualities” are also mentioned; that is, it anticipates contingencies in which someone other than the prime minister may have to, and will be able to, order the use of nuclear weapons.

Pakistan

The organisation responsible for formulating policy and exercising control over the development and Pakistan’s nuclear weapons use is the National Command Authority (NCA). Created in February 2000, the NCA has three components: the Employment Control Committee (ECC), the Development Control Committee (DCC) and the Strategic Plans Division (SPD). The military’s representatives are in a majority in all of them. The authority is meant to be chaired by the prime minister as head of government. But, in December 2007, Musharraf issued the NCA ordinance, which gave official cover to the body, removed it from any legal challenge, and made him (as president) the chairman. The authority has “complete command and control over research, development, production and use of nuclear and space technologies and , , , the safety and security of all personnel, facilities, information, installations or organisations.”[8] The ECC includes the head of the government and includes the cabinet ministers of foreign affairs, defence and interior; the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff committee (CJCSC); the military service chiefs; the director-general of SPD (a senior army officer), who acts as secretary; and technical advisers. This committee is thought to have been charged with making nuclear weapons policy, including the formulation of policy on the decision to use nuclear weapons. Pakistan’s conditions for use of its nuclear weapons have been outlined above.

The DCC manages the nuclear weapon complex and the development of nuclear weapon systems. It has the same military and technical members as the employment committee, but lacks the cabinet ministers that represent the other parts of government. The DCC is chaired by the head of the government and includes the CJCSC (as its deputy chairman), the military service chiefs, the director-general of the SPD and representatives of the weapon research, development and production organisations. These organisations include the A Q Khan research laboratory in Kahuta, the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, and the National Engineering and Scientific Commission (which is responsible for weapons development).

The SPD was established in the joint services headquarters under the CJCSC and is led by a senior army officer (who continues to lead it after his retirement). It has responsibility for planning and coordination and, in particular, for establishing the lower tiers of the command and control system and its physical infrastructure.

The 2003 revelations that while he was uranium enrichment program head, A. Q. Khan had been selling and sharing enrichment technology and weapons information with Iran, Libya, North Korea, and perhaps others have raised important questions about Pakistan’s control over its nuclear complex. The U.S. has been helping Pakistan secure its nuclear weapons complex. This has involved supply of about $100 million worth of support and equipment since September 11, 2001, including intrusion detectors and ID systems, and nuclear detection equipment.

The Machinery of Mass Destruction

The most visible sign of the growing capability of the respective nuclear complexes is the frequent testing of a diverse array of nuclear-capable missiles. Some of these tests are now carried out by military units rather than scientists and engineers, and implies some missiles are deployed as military systems with attendant command and control structures. India has also developed or otherwise acquired components of an early warning system and an anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defence system (Ramana, Rajaraman and Mian 2004).

The development of missiles carries grave risks in South Asia. Geography makes ballistic missile flight times from India or Pakistan to the other country’s cities as short as five minutes and possible warning times would be shorter (Mian, Rajaraman, and Ramana 2003). There would be no time at all for decision-makers to check the facts, to assess the situation, to consult, or weigh options. There will be pressure to move to a planned, predetermined, response. If such a response involved launch on warning, a posture that might have military backing (Ramana 2003), there would be a significant possibility of accidental nuclear war.

India

India has been developing land-based missiles and missiles that can be fired from sea, including from submarines. It also has aircraft able to drop nuclear bombs.

The main land-based nuclear delivery system is the Agni series of missiles. Work on the Agni started as part of the Integrated Guided Missile Development Program in 1983, but the missile has been substantially redesigned since the 1998 nuclear tests. The early Agni had both solid and liquid propellants and was never deployed.

Chronologically, the first of the missiles currently in the arsenal is Agni-2 with a range of 2,500 km. This missile’s first test was in April 1999 and the second test was in January 2001 (Mehta 2004). The third test was conducted in August 2004 with participation from the armed forces (Subramanian 2005). In October 1999, Agni-1 was “undertaken as a crash project . . . to cover the gap in range between the Prithvi-2 (250 km) and the Agni-2 (2,500 km)” missiles. The missile was first tested in January 2002 with a range of 700 km (Aneja and Dikshit 2002). The army and the air force are known to have fought over who would get control over these missiles (Sawant 2002).

The most recent missile in this series is 3,500 km-range Agni-3, which was first tested in June 2006. The test was a failure (Special Correspondent 2007). The next tests in April 2007 and May 2008 were declared successful (Subramanian and Mallikarjun 2008). Defence officials claim Agni-3 “can destroy targets in any country in south, east and south-east Asia” (ENS 2008). Agni-3 is still under development and is to be handed over to the army after one or more user trials (Subramanian 2008).

The navy has also laid claim to missiles. The first missile developed for the navy is the Dhanush, a variant of the Prithvi missile that was to be fired from a ship. Since the first test in April 2000, the launches have failed (PTI 2002). The missile has a range of 350 km with a payload of 500 kg (Special Correspondent 2007). The second naval missile is the Sagarika, also called the K-15, with a range of 700 km. Perhaps because of the difficulties with the initial Dhanush test, the first four Sagarika launches were kept a secret; only the successful fifth test in February 2008 was publicly announced (Subramanian 2008). The scale and complexity of the missile program has helped to drive a burgeoning military-industrial complex that brings together the Defence Research and Development Organisation, government laboratories, public sector and private companies, and universities. The Agni-3 project, for example, has involved over 250 firms, several research laboratories, and academic institutions (Gilani 2007; Rediff 2008).

Pakistan

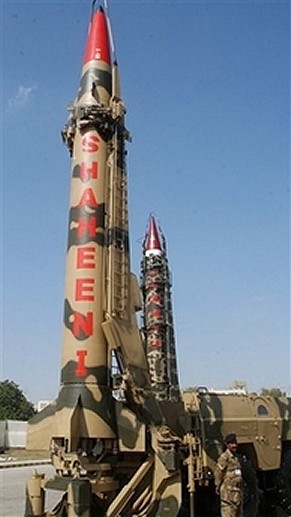

Pakistan has developed three types of ballistic missiles that are considered capable of delivering a nuclear warhead (Norris and Kristensen 2007). These are the Ghaznavi, Shaheen, and Ghauri.

Though the short-range Ghaznavi was said to have entered service in 2004, it was only in 2006 that it was declared ready for operations. The solid-fueled Shaheen comes in two varieties, a short-range Shaheen-1 and a medium-range Shaheen-2. The latter was flight tested on February 23, 2007, to a range of 2,000 km. The liquid-fueled Ghauri, derived from a North Korean missile, was first tested in April 1998, a month before the nuclear weapon tests. Recent Pakistani missile tests have been carried out by the various strategic missile groups (each equipped with a particular type of missile) of the army’s strategic force command and are described as “field exercises.” The 1,300 km-range Ghauri missile and the 700 km-range Shaheen-1 were tested by the army strategic force command in 2006. The first test launch of the Shaheen-2 missile by an army strategic missile group was carried out in April 2008 (AP 2008).

Pakistan has also developed a 500 km range cruise missile, the Babur, which has been described as “low-flying, terrain-hugging missile with high manoeuvrability, pinpoint accuracy, and radar-avoidance features” (Garwood 2006). The most recent test of this cruise missile, in May 2008, was described as “validating the design parameters of the weapon system” and implies the missile is still in the development phase (AFP 2008). Pakistan may eventually seek to arm its submarines with nuclear-capable cruise missiles.

Fuel for Bombs

The two basic materials used to make nuclear weapons are plutonium and highly enriched uranium. A simple first-generation nuclear weapon can be made with either about 5 kg of plutonium or about 25 kg of highly enriched uranium. More advanced weapon designs use less material. At the time of the nuclear tests, India was estimated as having a weapon-grade plutonium stockpile of about 300 kg, sufficient for about 60 weapons. Experts estimate that Pakistan now has about 550 kg (enough for just over 100 simple weapons). These estimates assume India used only the CIRUS and Dhruva reactors at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre complex to produce weapons plutonium. These reactors do not produce electricity. During the negotiations and public debates surrounding the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal, the atomic energy department insisted on keeping nine nuclear reactors to be used for electricity production outside international safeguards. This includes eight heavy-water reactors, and the prototype fast-breeder reactor (PFBR) being constructed in Kalpakkam near Chennai. All are much larger than CIRUS and Dhruva. By keeping them outside international inspection, India ensures they can be used also to make weapons-grade plutonium.

A study for the International Panel of Fissile Materials, which we cowrote, shows that if there is sufficient uranium available to fuel them each heavy water reactor can produce about 200 kg of weapon-grade plutonium every year (Mian et al. 2006). Similarly, the PFBR can produce about 140 kg of weapon grade plutonium every year if it operates at 75 percent efficiency (Glaser and Ramana 2007). Pakistan has relied on highly enriched uranium from its Kahuta centrifuge enrichment plant for most of its nuclear arsenal so far. It is estimated to have about 1,400 kg of this material, enough for perhaps 60 weapons, and to be producing on the order of 100 kg per year (an additional four weapons a years) (ibid.). Pakistan also has a plutonium production reactor at Khushab that may yield about 10 kg a year (about two weapons worth). It may have accumulated a plutonium stockpile of about 80 kg — enough for roughly 15 weapons.

As a response to the nuclear deal, Pakistan’s NCA, which Musharraf chaired, declared that “In view of the fact the [US-India] agreement [that] would enable India to produce a significant quantity of fissile material and nuclear weapons from unsafeguarded nuclear reactors, the NCA expressed firm resolve that our credible minimum deterrence requirements will be met” (Sheikh 2006). A former Pakistani foreign minister has proposed building a second Kahuta uranium enrichment facility as a way to keep up with India (Sattar 2006). Pakistan may also have moved from the first- and second-generation centrifuges that Khan exported to Libya, North Korea, and Iran to more powerful machines (Hibbs 2007, 2007). As these machines come online, Pakistan’s production capacity and inventory of highly enriched uranium could increase significantly. Pakistan also appears to be building two new plutonium production reactors at Khushab (Warrick 2006; Broad and Sanger 2006). Work on the last of these appears to have started in 2006 (Albright and Brannan 2007). Each of these new reactors may be the same size as the existing reactor at the site. Once operational, these reactors would allow a rapid increase in Pakistan’s stock of weapons plutonium.

Conclusion

Ten years after the nuclear tests, leaders in India and Pakistan are supporting and funding their militaries’ preparations to fight nuclear wars. A war and a subsequent military crisis, a decade of political turmoil in both countries, changes in government in India, a coup and transition to democracy in Pakistan, and countless rounds of peace talks, have failed to bring meaningful changes or restraint in nuclear policy. National leaders and armed forces remain committed to nuclear weapons. The guiding principle of the respective nuclear postures remains the achievement of a capacity for MAD. At the same time, leaders tell each other and the public that they are committed to establishing peace between the two countries. This is an impossible contradiction. As Albert Einstein noted “You cannot simultaneously prevent and prepare for war.” The most that can be gained is a hostile, crisis-ridden, and costly search for advantage that is known as a “cold war.”

The remorseless momentum driving the nuclear weapons and missile programmes of the two countries needs to urgently be slowed. The instability already unleashed by the prospect of an Indo-U.S. nuclear deal needs to be addressed. There is much that can be done. The obvious first steps are to freeze nuclear weapon production, halt further missile tests, and renounce military doctrines that involve or could trigger the use of nuclear weapons. Failure to deal with the nuclear realities at work in the subcontinent runs the risk that India and Pakistan will succumb to the bomb’s MAD logic. Otherwise, the bomb will take on a life of its own as it has in the U.S. and Russia after the Cold War. It will transcend politics and purpose. Even if it is not used, it will poison the prospects for a peaceful future.

Zia Mian is a research scientist with the programme on science and global security, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University. He is the coeditor of Out of the Nuclear Shadow: Pakistan’s Atomic Bomb & the Search for Security (Zed Books, 2001).

M. V. Ramana is a physicist at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment and Development in Bangalore, India.

This article was published in the Economic and Political Weekly on June 28, 2008. Published at Japan Focus on July 12, 2008.

Notes

[1] “National Technology Day Celebrated,” Press Information Bureau, Government of India, May 11, 2008.

[2] “A Decade of Responsibility and Restraint,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Pakistan, May 28, 2008.

[3] Text of Joint Statement on Pakistan-India ministerial-level talks, May 21, 2008.

[4] See Subrahmanyam (1990), Chellaney (1999), and Zehra (1997).

[5] For example, in June 2002 an Indian army officer revealed plans for a quick attack on Pakistan, adding that there was only “the slimmest chance” of nuclear weapons being used in retaliation (Bedi 2002).

[6] The NSAB is supposed to be independent of the government, but it is dominated by exbureaucrats (Babu 2003).

[7] For example, foreign minister Jaswant Singh explicitly admitted in the Rajya Sabha on December 16, 1998 that “The minimum is not a fixed physical quantification” (Rajagopalan 2005, 73).

[8] National Command Authority Ordinance, Government of Pakistan, December 13, 2007.

References

AFP (2008): “Pakistan Test-fires Nuclear-capable Cruise Missile: Military,” Agence France-Presse, May 8.

Ahmed, Firdaus (2004): “The Calculus of ‘Cold Start,’” India Together, May.

Akram, Munir (1999): “Indian Nuclear Doctrine: Statement by Pakistan’s Ambassador” in Conference on Disarmament, Geneva.

Albright, David and Paul Brannan (2007): “Pakistan Appears to be Building a Third Plutonium Production Reactor at Khushab Nuclear Site,” Institute for Science and International Security, June 21, 2007 .

Aneja, Atul and Sandeep Dikshit (2002): ‘Short-range Agni Test-fired’, Hindu, January 26.

Anonymous (2000): “Benazir Vetoed Kargil-style Operation in 1996,” Indian Express, February 8.

AP (2008): “Pakistan Launches Longest-range Nuclear- capable Missile during Exercise,” Associated Press, April 21.

Babu, D Shyam (2003): “India’s National Security Council: Stuck in the Cradle?,” Security Dialogue 34 (2): 215–30.

Bedi, Rahul (2002): “India Plans War within Two Weeks,” Daily Telegraph, January 6.

Bidwai, Praful and Achin Vanaik (1999): South Asia on a Short Fuse: Nuclear Politics and the Future of Global Disarmament, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Broad, William J and David E Sanger (2006): “US Disputes Report on New Pakistan Reactor,” New York Times, August 3.

Chellaney, Brahma (1999): “The Defence of India,” Hindustan Times, October 20.

DN (2006): “Indian Military Rehearse Pakistan’s Dissection in Mock Battles,” Defense News, May 3.

Ellsberg, Daniel (1981): “Call to Mutiny” in E. P. Thompson and D. Smith (eds.), Protest and Survive, Monthly Review Press, New York.

ENS (2008): “Agni-3 Missile Test-fired Successfully,” Indian Express, May 8, 1.

Ganguly, Sumit and Devin Hagerty (2005): Fearful Symmetry: India-Pakistan Crises in the Shadow of Nuclear Weapons, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Gardner, David (2000): “Subcontinental Stand-off,” Financial Times, February 22.

Garwood, Paul (2006): “Pakistan Test-Fires Cruise Missile,” Associated Press, March 21.

Gilani, Iftikhar (2007): “India Developing ICBM with 5,500 km Range,” Daily Times, April 14.

Glaser, Alexander and M V Ramana (2007): “Weapon-Grade Plutonium Production Potential in the Indian Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor,” Science and Global Security 15: 85–105.

Grimmett, Richard F (2007): Conventional Arms Transfers to Developing Nations, 1999-2006: Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, Congressional Research Service, U.S. Congress, September 26, 2007, available here.

Hibbs, Mark (2007): “P-4 Centrifuge Raised Intelligence Concerns about Post-1975 Data Theft,” Nucleonics Week, February 15.

——— (2007): “Pakistan Developed More Powerful Centrifuges,” Nuclear Fuel, January 29.

IANS (2006): “Indian Army Tests Its New Cold Start Doctrine,” Indo-Asian News Service, May 19.

IE (2006): “Cold Start Simulations in May,” Indian Express, April 14.

Karnad, Bharat (2002): “India’s Force Planning Imperative: The Thermonuclear Option” in D. R. SarDesai and R. G. C. Thomas (eds.), Nuclear India in the Twenty-First Century, Palgrave, New York.

Martellini, Maurizio and Paolo Cotta-Ramusino (2002): “Nuclear Safety, Nuclear Stability and Nuclear Strategy in Pakistan,” Landau Network–Centro Volta.

McKinzie, Matthew, Zia Mian, A. H. Nayyar, and M. V. Ramana (2001): “The Risks and Consequences of Nuclear War in South Asia,” in S. Kothari and

Z. Mian (eds.), Out of the Nuclear Shadow, Lokayan and Rainbow Publishers, New Delhi.

Mehta, Ashok K (2003): “India Was on Brink of War Twice,” Rediff on the Net, January 2.

——— (2004): “Missiles in South Asia: Search for an Operational Strategy,” South Asian Survey 11 (2): 177-192.

Mian, Zia, A. H. Nayyar, Sandeep Pandey, and M. V. Ramana (2001): “What They Can Agree On,” The Hindu, July 10.

Mian, Zia, A. H. Nayyar, R. Rajaraman, and M. V. Ramana (2006): “Fissile Materials in South Asia: The Implications of the US-India Nuclear Deal,” International Panel on Fissile Materials.

Mian, Zia, A. H. Nayyar, and M. V. Ramana (2004): “Making Weapons, Talking Peace: Resolving Dilemma of Nuclear Negotiations,” Economic & Political Weekly 39 (29).

Mian, Zia, R. Rajaraman and M. V. Ramana (2003): “Early Warning in South Asia: Constraints and Implications,” Science and Global Security 11 (2–3).

Mian, Zia and M. V. Ramana (1999): “Beyond Lahore: From Transparency to Arms Control,” Economic & Political Weekly 34 Saturday Review of Literature, March 2.

Norris, Robert S. and Hans M. Kristensen (2007): “Pakistan’s Nuclear Forces, 2007,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June, 71–74.

NSAB (1999): “Draft Report of National Security Advisory Board on Indian Nuclear Doctrine,” National Security Advisory Board, New Delhi.

Pant, Harsh V. (2007): “India’s Nuclear Doctrine and Command Structure: Implications for Civil-Military Relations in India,” Armed Forces and Society 33 (2):238-264.

PMO (2003): “Press Release: Cabinet Committee on Security Reviews Progress in Operationalising India’s Nuclear Doctrine,” Prime Minister’s Office, Government of India.

PTI (2002): “More Tests of Danush Missiles Will Be Carried Out: India,” Indian Express, February 18.

Rajagopalan, Rajesh (2005): Second Strike: Arguments About Nuclear War in South Asia, Penguin, New Delhi.

Rajaraman, R., Zia Mian and A. H. Nayyar (2004): “Nuclear Civil Defence in South Asia: Is It Feasible?,” Economic & Political Weekly 39 (46-47): 5017–26.

Ramana, M. V. (2003): “Risks of LOW Doctrine,” Economic & Political Weekly, 38 (9).

Ramana, M. V. and Zia Mian (2003): “The Nuclear Confrontation in South Asia” in SIPRI Yearbook 2003, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ramana, M. V., R. Rajaraman and Zia Mian (2004): “Nuclear Early Warning in South Asia: Problems and Issues,” Economic & Political Weekly 39 (3).

Rediff (2008): “Here’s How Agni Missile Can Strike Farther,” Rediff News, May 13.

Riedel, Bruce (2002): “American Diplomacy and the 1999 Kargil Summit at Blair House: Centre for the Advanced Study of India,” University of Pennsylvania.

Sattar, Abdul (2006): “Response to US Discrimination,” Pakistan Observer, March 22.

Sawant, Gaurav (2002): “Agni Missile Falls into Army’s Kitty,” Indian Express, May 16.

Schwartz, Stephen I (1998): “Introduction,” in S. Schwartz (ed), Atomic Audit, Brookings, Washington.

Sheikh, Shakil (2006): “Pakistan Vows to Maintain Credible N-deterrence,” The News, April 13.

Shukla, J. P. (2002): “No Weapon Will be Spared for Self-defence: PM,” Hindu, January 3.

Special Correspondent (2007): “Agni Passes Test in Missile Milestone,” Telegraph, April 13.

——— (2007): “Dhanush Missile Test-fired,” Hindu, March 31.

Subrahmanyam, K (1990): “The Nuclear Option,” Times of India, January 5.

——— (2003): “Essence of Deterrence,” Times of India, January 7.

Subramanian, T. S. (2005): “A Success Story,” Frontline, October 7.

Subramanian, T. S. and Y. Mallikarjun (2008): “Agni-III Test-fired Successfully,” Hindu, May 8.

Subramanian, T. S. (2008): “Full of Fire,” Frontline, May 24.

——— (2008): “Strike Power,” Frontline, March 28.

ToI (2006): “Army Conducts Largest Ever War Games in Recent Times,” Times of India, May 19.

Vanaik, Achin (2002): “Deterrence or a Deadly Game? Nuclear Propaganda and Reality in South Asia,” Disarmament Diplomacy (66).

Warrick, Joby (2006): “Pakistan Expanding Nuclear Program,” Washington Post, July 24.

Zehra, Nasim (1997): “Defence Budget 1997–98: Compulsion Not Options,” Nation, June 26.