Miyake Shoko

Translated by Adam Lebowitz

This conversation is adapted from a longer roundtable discussion on the social responsibility of poetry that appeared in the September issue of the literary monthly Shi to Shiso (Poetry and Thought). It features an analysis of the Abe administration’s then-proposed “reforms” to the Education Law (Kyoiku Kihonho) by

The administration’s education reform bill, with its echoes of prewar nationalist education, passed into law on December 15, 2006, with ratification by the Upper House of the Diet.

Following this discussion, the translator presents text and illustrations from Kokoro no Noto (Notes for the Heart), a patriotic textbook for primary and junior high school students that was published by the Ministry of Education in 2002.

Nakamura Fujio: Joining us today is Professor Miyake Shoko from the

Miyake Shoko: My research has been on Walter Benjamin and the German-Jewish schools of thought. He was foremost in considering the impact of reproduced images—photography, cinema—on culture, even while composing texts of incredibly fine linguistic minutiae. In my classes on the “culture of images” we analyze texts and visuals, for example, to understand conceptualizations of nation and citizenry, how images of these are produced and consumed, and the complicated notions of authority, resistance, powerlessness, and acceptability that arise. In general these were simply research problems for me and I didn’t consider connections to the debate surrounding education reform, that is until recently when I read Kokoro no noto (Notes for the Heart) that the Education Ministry published in 2002. The “Notes” are meant to be educational material on morality distributed to primary and junior high school students. My two children at that time were both of primary school age.

I sat down at my child’s desk and read. As I worked my way through the text I kept asking myself: Whose voice is this supposed to represent, and to whom is it talking? Finally I was left with this chilling feeling, along with the very clear impression of what this text with its colorful images was supposed to provide for targeted students from the first grade through to the last year of junior high, in total nine years of compulsory education. The Education Reform Bill campaign was then in full swing, and on March 20, 2003, in fact the first day of air strikes on the Iraqi capital

Nakamura Fujio: Mathematician and essayist Fujiwara Masahiko has come out with a popular selling book recently entitled Kokka no Hinkaku (National Dignity). Although there is not much to be said of its contents, its influence cannot be ignored. 200,000 copies of the first edition have been sold. Basically he urges the necessity of feeling over reason, the national language over English, and the bushido psychology over democracy because through these

From looking at the Reforms, I would say that the government’s aim is to place patriotism on a level with religion as a means of restoring “dignity”. It is us as poets who must be aware of the forces pressing for change. Prof. Miyake, I’d like to hear your comments about this.

Miyake Shoko: The ruling coalition (Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito) has inserted the term “patriotism” (aikokushin) in Article Two of the Reform bill. First, let’s examine the ideology of the existing law spelled out in the Preamble and Articles One, Two, Six, and Ten. The Preamble announces: “Education has the authority to realize the ideals proscribed in the Constitution.” Article One states the goals of education as, “Seeking to perfect character (jinkaku no kansei) . . . (and) respecting the value of the individual.” This is in contrast with the pre-war education system which strove to create subjects “for the sake of the Nation” (Okuni no tame). In order to fulfill this goal, Article Two as a plan (hoshin) emphasizes freedom (jiyu) such as “curricular freedom” (gakumon-jiyu) and “self awareness” (jihatsuteki-seishin).

Finally Article Ten, concerned with educational authority, states, “Education will not exert undue influence, and has a direct responsibility towards all its citizens,” meaning that education does not serve the nation but the children of its citizens. The nation cannot determine the direction education is supposed to take. It can only enact provisions for the goals already stated. Under Article Six explaining the function of schools, the instructor’s mission (shimei) is to be in service to all (zentai-no-boshisha), not to the emperor or the nation state.

The “Reforms” preserve some of this language, but through a trick of context completely change the meanings. Article One language “perfecting character” remains but “respecting the value of the individual” has been stricken. The intent of Article Two is changed from “plan” to “target” (mokuhyo), meaning the state decides the meaning of “perfect”.

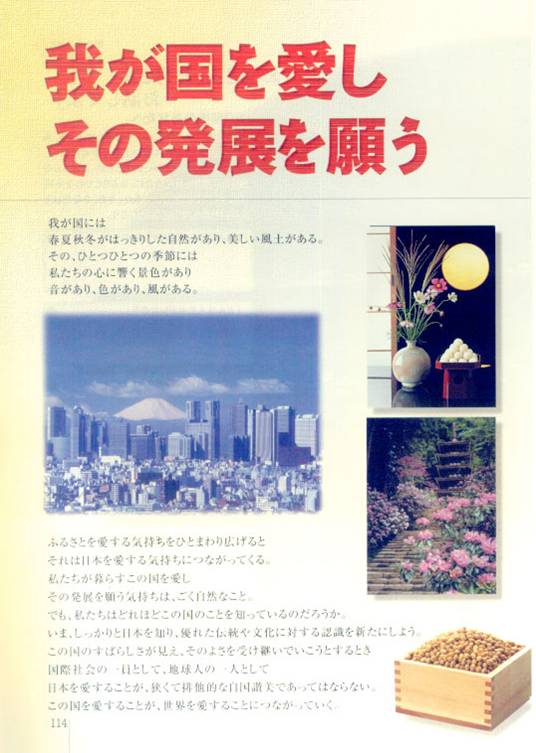

In parts one to five of Article 2 the terms “moral character” and “common sentiment” are followed by the “heart” and “attitude” in Article 20. Moral teachings are constituted in school lessons, meaning legal enforcement of the contents of the Kokoro no Noto. The text’s patriotic Chapter Five “Aikokushin” is as follows: “Together with cultivating feelings of respect for tradition and culture, and loving our country and the hometown that raised us, cultivating respect for other countries and an attitude that contributes to the peace and development of the international community.”

In Article One “perfection of character” was previously enunciated as “each individual’s value” and “freedom”, meaning that the right of each individual to develop his or her own human character was guaranteed. In the reformed version, the first article is followed by Article Two containing over twenty provisions (more than even pre-war regulations) described as “goals” concerning morality. Morality, as in the pre-war period, functions within parameters defined by the state. As the high school science teacher Yoshida-san can attest, it is these “goals” and also “attitudes” that have become the standards of evaluation.

“Feelings/Desires/Attitudes” (Kanshin/Iyoku/Taido) have become categories on the report card for each subject. In 2002 the terms “Patriotic Heart” (Kuni wo aisuru kokoro) and “Japanese Self-Consciousness” (Nihonjin toshite jikaku) first appeared in the Primary School Registry and currently appear on the report cards of over 190 schools. My fear is that under the reforms all schools will be mandated to give A-B-C grades to these as part of the “goals.”

Then there is Article Ten whose meaning is perverted in the most dreadful way. Until now “Education will not exert undue authority” was the school’s—the teacher-student relationship’s—main protection against interference from government authority. In the “reformed” version this clause remains but the following one is changed. Before it read, “This should be considered education’s main responsibility to all citizens”. But now in its place will read, “This should be according to this law and all others.” And you will recall that the stated goal of Article Two is “A patriotic attitude towards our country.”

Also, where it simply says now that “provisions have been created” for the educational authorities to reach their goals, the reform version states, “With the cooperation of the state and the regional public authorities, to be accomplished in a correct manner,” the state “has established comprehensive educational facilities”, the regional public authorities “in similar sentiment have established facilities” and taken “financial measures”, underlining the possibility that the state will decide curriculum as well. In addition, the subject of Article Seventeen is no longer the educational authorities (kyoiku-gyosei) but “government” (seifu). With the educational setting under the long reach of the government “all plans concerning the promotion of education must be made public and announced in the National Diet”, but this means anything can be enacted as long as it is announced. Looking at the second clause, regional authorities are required to “make allowance” (sanshaku) and “with all power follow these rules”, meaning they have become subordinated to central authorities in all matters relating to curriculum.

What this all means is that while “education shall not exert undue authority” still appears in this document, the meaning of education has been subverted entirely. Since the new version states, “Education as determined by the education authority will not exert undue influence,” the issue of “undue influence” will no longer be pertinent. In other words, the new law enables the educational authorities to be completely in control without having to heed criticism from teachers, parents, or civic movements.

This is what I want to draw attention to. Education has been under the scrutiny and counsel of the citizenry; new laws make it the mouthpiece of government authority. And it is happening simultaneously to the LDP’s efforts to change the Constitution. For example, where Articles Twelve and Thirteen now read “For public welfare” (Kokyo no fukushi), will change to “For public benefit and order” (Koeki oyobi Ko no chitsujo). A cooperative society protecting the rights of the minority is encouraged in the former statement. After it is discarded we will have the law of the jungle because it is clearly stated that the “public” will have precedence over the “individual”. “Public” in this context does not mean informed “public citizens” who have the right to criticize the government; public—stressing the importance of “national interest” and the suppression of private thought—is synonymous with “state”, and to me it is the language of a state that does not respect the rights of the individual or the weak.

Nakamura Fujio: Is it possible to actually “love” a state? I bring this up because discussions about reform are premised on a decline of educational and moral standards. To me it seems the state is taking these actions in the face of what it perceives are a dissolution of individual morality. It fears its own existence will be compromised if individuals refuse to acknowledge it as part of their subjective outlook. Yoshida-sensei, as a high school teacher what do you think of this in light of what Prof. Miyake has spoken about?

Yoshida Yoshiteru: I’d have to agree. You know, when I took my qualifying examinations we were required to commit Articles One and Two to memory. I’m teaching at a private high school at the moment where I believe we have comparatively more freedom. Now, the reason I chose to work here goes back to my initial interview with the public system, where I was asked, “What would you do if you found yourself in conflict with your superiors?” This question, which took me aback, has nothing to do with being qualified and being forced to follow would in the long run be detrimental to my work as an educator. This is why I chose to work at a private institution.

Miyake Shoko: Under current law the correct answer would probably be along the lines of, “I would fulfill my responsibility to the citizenry.” When they find themselves at odds with their superiors, the correct mission of the teacher is to serve all, that is protect the child’s right to receive an education.

Yoshida Yoshiteru: At the time I said something along the lines of, “I would think of myself as a student, and then base my decision on what options are available from both perspectives.”

Miyake Shoko: The reform legislation takes this choice away. In practice more and more teachers would be disciplined for not listening to their principal.

Yoshida Yoshiaki: That’s certainly the impression I’ve received from the public school teachers I’ve been talking to. When I think back to my own education through high school my teachers were very intensely involved with the National Teacher’s

It’s certainly feasible to teach children about the kinds of laws that exist in this country but it should end there. One very good point about the present system is that it approaches education from the position of the people, and from my own experiences as a teacher I can tell you that whatever the Education Law may state the classroom has its own reality. If these big changes occur and we’re supposed to become more nationalistic, I really don’t know how we are supposed to function as teachers. If public school teachers aren’t allowed to raise their hands in meetings and are punished for not standing during the singing of “Kimigayo” they’re basically being told not to have any opinions. It’ll make for a contradictory situation. How to make the best of it? I personally don’t have an answer.

Miyake Shoko: It’s not only Articles One and Ten that are being changed, it’s the whole tenor of the Law. And it’s not going to make life difficult only for teachers. In actual fact Article Two affects every aspect of public and private life outside of the school. This includes the systematic relationship between school, home tutoring, home, and community, not to mention continuing, adult, and pre-school education programs.

Yamamoto Seiko: As a mother with children in the education system my first issues with this debate are how they are going to be affected. Even before the introduction of the Reforms things have been moving in the direction outlined by them for some time. Feelings, desires, attitude, all of these concepts have become items for appraisal which means that school is assuming an increasingly parental role. And why is that? From the opposite angle we can argue, “The State has been disappearing, and it doesn’t even realize it,” and that might be exactly what the people creating these rules have feared.

Nakamura Fujio: So what’s to be done?

Miyake Shoko: Well, first off we have to make it clear the reforms are not the right thing to do. Consider the textbook Kokoro no Noto. It is a nationally registered textbook; as such, its message is that individual character is to be created by the State and not develop naturally. This follows the spirit of Article 10 of the new Education Law. The teacher in

Through the attitude of control of children, and the overall proposed changes to the Constitution, what exactly is sought? It is a conceptual issue of law, the state and violence, and it is helpful to refer to Walter Benjamin’s Critique of Violence. Writing after World War I, he theorized that the nation is able to monopolize violence through law. Domestically the use of force is the agency of the police, but in foreign affairs the army is the instrument of state violence. Even though private security forces operate they do so within international laws that are set not by corporations or by NGO’s but by nations. I think that there is an intimate connection between this issue and the attempts by the state to enforce patriotic “hearts” of the populace through education.

Translator’s Afterword: Moral Education and Kokoro no Noto

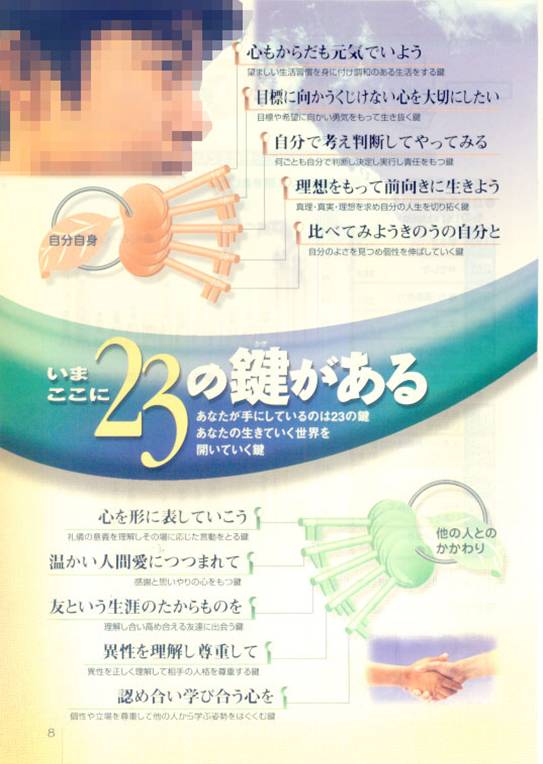

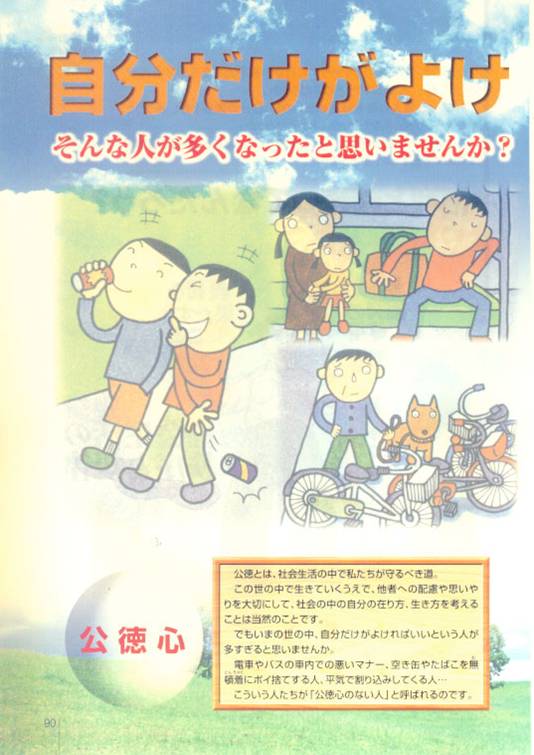

The Education Ministry’s new patriotic textbook Kokoro no Noto (Notes for the Heart) is filled with color photos and illustrations interspersed with text and visual data (graphs, pie charts, etc.). The focus of instruction is on morality, beginning with cultivation of the correct individual attitude, extending towards mannerly interaction with school and community, and then encompassing a wider ideological love of country. The text reads remarkably like a religious pamphlet; students are asked rhetorical questions and then instructed to reject answers that appear immoral. Morality-based designs for living (see the 23 Keys below) are offered. Another striking feature is the message that individuality is best fulfilled within group contexts and social ills are the result of too much individuality. The final section is devoted to the dignity of work, the importance of family, and patriotism. The final pages devoted to the “International Community” are, as the samples indicate, paternalistic. Patriotism aside, the political message is ideologically conservative with its emphasis on individual responsibility as the basis for social reward.

An adapted version of this text is currently in use in my son’s first grade public school class, which leads me to believe it is widely used. It is particularly questionable if such a text is appropriate in a school with a large foreign/bi-national population.

The text can be viewed in full at: www.cebc.jp/data/education/gov/jp/konote/cyu/.

Cover of Kokoro no Noto

“The 23 Keys to life”

“There certainly seem to be more selfish people lately”

“An equal and fair society” / “Absence of duty is absence of bravery”

“Cultivating a Love of Country” / “Beautiful Language, Beautiful Seasons”

“You have been entrusted with the continuation of Japanese culture and tradition”

“Thinking of World Peace and happiness of mankind”

This article was posted at Japan Focus on December 23, 2006.

Adam Lebowitz is a teacher and translator who has lived in Japan for 15 years and is now at Tsukuba University in Ibaraki Prefecture. He is a co-editor of Jikai, a Japanese-language poetry journal, and a Japan Focus Associate.