Miyagi Yasuhiro

Introduced and translated by Miyume TANJI

Introduction

So much has happened to the Okinawan protest against the Futenma base relocation in the past 10 years: the formal and informal local resistance has been such that the new

Miyagi requires no introduction to Japan Focus readers. [1] He is an articulate activist against the relocation. Born in Nago in 1959, he pursued a stage acting career in

The report centers on the political economy of

1. Democracy: Elections and Poll Results

Futenma Air Base Relocation Site: Kadena,

First, it is necessary to review the crucial decisions on base relocation ten years ago. In April 1996, SACO (the Special Action Committee on Okinawa) agreed on the return to

1) The northwest forest area within the Kadena Ammunition Storage Area (cancelled due to local opposition);

2) The Kadena Air Force Base, within which the Futenma Air Station facility might have been integrated (stalled due to opposition from the US Air Force and from the three municipalities where Kadena base is located);

3) Reclaimed land on a coastal area adjacent to

4) The

5) In the end, the U.S and Japanese governments agreed in the SACO final report on a site: the coastal area adjacent to

Events Leading to the Nago Referendum, December 1997

In April 1996 Nago Mayor Higa Tetsuya, agreed to the Defence Agency’s preparatory investigation of the

In June, at the City Assembly, the Mayor called for a consensus formation among citizens without a referendum.

In August, the

More than half of the eligible voters signed a petition organized by the Nago Referendum Promotion Committee calling for a referendum legislation bill.

Nago City Assembly rejected the original referendum bill, under which voters were simply asked to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to base construction, and instead passed a bill offering four choices adding the option to choose ’yes” subject to the condition of ‘increased environmental protection and economic regeneration’ (see Figure 1).

The referendum campaign started, and the competition between supporters and opponents of the new base heated up. The main supporters were those engaged in local construction industry and chambers of commerce, hoping for economic regeneration and increased government subsidies.

The government of

Figure 1. Referendum results (voting rates 82.45%)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Election of the Mayor of

Election of the Mayor of

‘I hereby accept the heliport construction; at the same time, I am resigning from office and ending my political career.’ ——24 December, 1997, former mayor Higa Tetsuya, at Prime Minister’s residence.

‘The offshore heliport issue will be suspended, until the Governor of

Subsequent to Higa’s resignation, the base opponents agreed to support Tamaki Yoshikazu, Member of the Prefectural Assembly.

‘The focus of this election is to publicly declare our opposition to the marine base, both inside and outside the community.’ —–21 January 1998, Tamaki Yoshikazu at the Citizens’ Rally, ‘Forest of 21st Century’ Gymnasium in

‘I have come to the decision that

Candidates’ comments with regard to Governor’s opposition to the heliport (as reported in

Tamaki:

The purpose of this election is to enable the new mayor and the local residents to stop the construction of a new military base. The referendum showed the opposition of the majority of citizens, but the former mayor went against the citizens’ will by accepting the heliport at the prime minister’s residence, then resigning from office. This is outrageous. The government has not given up. Following the Governor’s decision to reject the heliport, the most important goal is for

Kishimoto:

On the offshore heliport issue, I have reiterated, ‘I will wait for the Governor’s decision.’ Now that the Governor has expressed his opposition considering general circumstances in

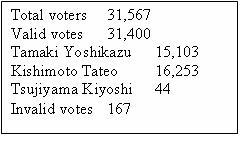

Figure 2. Election result (voting rate 82.35%) : Kishimoto Tateo 51.76% (Brown), Tamaki Yoshikazu 48.10% (Blue), Tsujiyama Kiyoshi 0.14% (Yellow)

Many voters who voted against the heliport at the referendum voted for Kishimoto at the mayoral election.

In November 1999, Governor Inamine Keiichi, victorious in the 1998 election, declared that the shore off Henoko next to Camp Schwab in Nago was the construction site of the new military ‘airport’, part of which would be available for local, commercial use. On 27 December, Kishimoto Tateo, Mayor of Nago, conditionally accepted this, and, on the following day, the Cabinet Meeting agreed on the ‘Policy on relocation of the Futenma Air Station’. The decisions made at this Cabinet Meeting adjusted to the conditions of acceptance by

In the following year, after the G8 summit in Kyushu and

In July 2002, the basic plan for the Futenma replacement facility was agreed. In February of the same year, Kishimoto, incumbent mayor of Nago, was re-elected, defeating relocation opponent (this author) by the substantial margin of 9,000 votes (20,356 to 11,148). In November, Governor Inamine was also re-elected by a significant margin, 359,604 votes to Mr Yoshimoto’s 148,401, and Mr Aragaki’s 46,230.

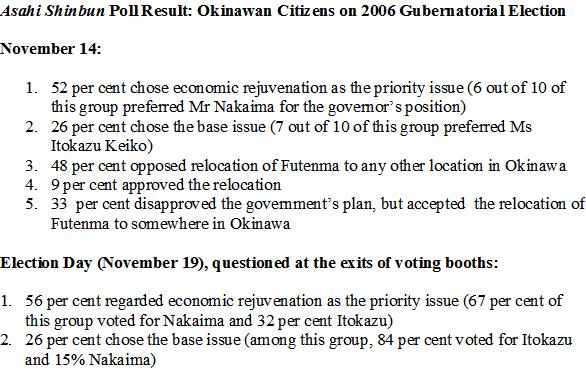

The ‘Public Opinion Paradox’: The Election and Poll Result

The conflicting results of the 1997 referendum and the 1998 mayoral election have been referred to as the ‘public opinion paradox’. Okinawan voters responded to opinion polls by opposing the new military base construction; but at election times, they placed greatest importance on economic rejuvenation and implicitly accepted construction of the new base.

Taking these results into consideration, the parties opposed to the base tried to win by expanding their support base as much as possible. However, they lost both elections in 2006 – Governorship of Okinawa and Mayorship of Nago– partly because of the internecine divisions within the opposition camp.

On Election Day the media reported Ms Itokazu Keiko, the anti-base candidate, was likely to win, according to exit polls. The successor of the former Governor backed up by the LDP-Komeito coalition, Nakaima Hirokazu, nevertheless won, thanks at least in some measure to the absentee votes organized and collected by local companies before the Election Day.

In choosing a candidate for the Nago mayoral election earlier in January 2006, the base opponents (and the progressive party supporters) suffered from the similar split that had plagued the gubernatorial election. For mayor of Nago, the opposition forces endorsed an unusually conservative candidate. Those who disapproved this decision, however, supported another candidate. Because of the inability to unify and concentrate oppositional votes, Mr Shimabukuro Yoshikazu, endorsed by the LDP-Komeito coalition, won the mayoral election. (Mr Kishimoto did not run this time, because of ill health, and he died shortly after the election.)

Just before the mayoral election, the

Both elections in 2006 raised serious concerns about the integrity of

1. Lack of transparency: pre-arranged absentee voting decided the election results.

2. Election promises that were ignored or assigned insufficient weight.

The most basic democratic principles are at stake. Yet the issue is not simply about the Okinawan citizens’ public awareness, or about how ‘democratic’ Okinawans are as a people. It is a question of the pressures inflicted on them by the Japanese government, which seems determined to use any means to achieve its objectives.

Elections and Political Activism

Only the government of

In Okinawa (perhaps not just in

The 1997 referendum was the expression of collective will of the citizens of Nago. It represented residents’ views. Does this indicate the existence of ‘civil society’? According to Douglas Lummis, the original definition of ‘civil society’ is ‘a realm separate from the government’.[2] The referendum in 1997 was an activity characteristic of a civil society, namely, not organized by the government. Indeed, it was all the more an act of civil society because the government persistently tried to interfere with it. We need a healthy civil society free from the ‘public opinion paradox’. Without it, Nago residents’ rejection of the marine base, expressed through the referendum, will never become a reality.

The difficulty is how to cultivate such a civil society, how to negotiate the gap between the politics of election and activism. Unfortunately we have not been able to do this, myself included.

The new base construction could start at any time, even though it has been stalled for a decade since the

The most urgent task for us is to overcome the gap between citizen activism and election politics.

2. The Political Economy of Okinawan Bases

Following the schoolgirl rape case in 1995, the indignation shown by the Okinawan people rose so as to threaten the Japanese government. The government responded with a series of economic compensation measures for Okinawa, in addition to inventing the

‘Shimada Commission’ Projects

In August 1996, a private consultative body was established under the Chief Cabinet Secretary. Formally named ‘Commission on Okinawan Cities, Towns and Villages hosting US Bases’, commonly it was known as the ‘Shimada Commission’ after its chair. Its aim was to reduce the local people’s frustration about the continuing military presence.

The ‘Shimada Commission’ provided funding on different terms:

- Projects previously impossible under a partial subsidy system were given 100 per cent government funding;

- The local governments of cities, towns and villages could negotiate directly with the Cabinet and the Defence Facility Bureau;

- Because the projects were not classified as ‘public works’, public funding would not be given when renovation was required in the future.

From 1997, 38 industrial projects and 47 plans were approved to proceed by stages towards completion in 2007. The total budget to 2006 was 75.54 billion yen, and 34 industrial plans had been completed by the time of the 2005 financial year.

Of municipal grants in the period up until 2005,

The Shimada Commission projects were assigned the role of integrating into the market economy public sector industries in municipalities encumbered with military bases. As Chair Shimada Haruo explained, ‘Above all, feasibility, competitiveness and self-sufficiency for market survival are required’.[3]

Shimada’s projects differ qualitatively from traditional Okinawan ‘public works’. They were used as part of the experiment to drastically alter the nature of governance along neo-liberal lines, as was later exemplified nationally in the privatization of

In response to the Okinawans’ reaction to the 1995 schoolgirl rape case,

Growing Base-related Income Dependence

Since being chosen as the site for base construction,

Nago’s income originating from military bases includes:

- Rent (asset revenue);

- Supplementary subsidies for cities, towns and villages hosting nationally-owned facilities;

- Projects subsidised by the Law related to the Maintenance of Livelihood Environment (mainly Clause 8: ‘Subsidised Projects for Stabilizing Residents’ Well-being’).

Since 1997 the following have also been added:

- Shimada Commission projects;

- Subsidies and grants to SACO-related projects;

- Public and non-public economic rejuvenation projects for the Northern region of

Okinawa ;s main island.

Base-related income increased two-fold between 1997, the year of referendum, and 1998 (from 2.38 billion to 4.766 billion yen), and then kept growing as the government of Japan and Okinawa Prefecture reached basic agreement in the Replacement Facility Committee, reaching around 9 billion by 2003.

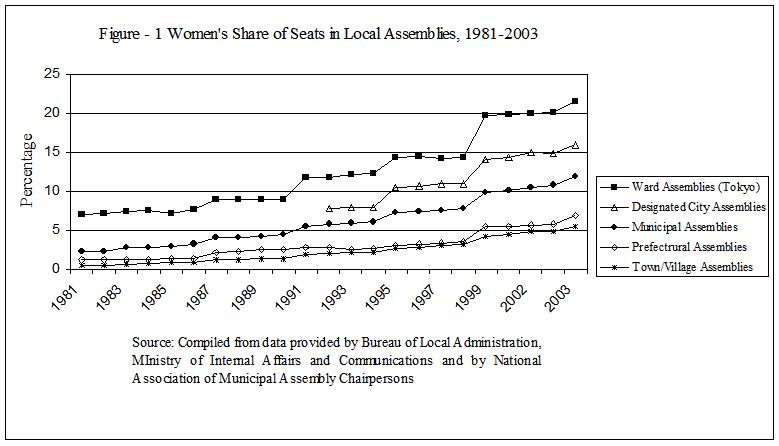

Figure 3. Ratio of Military Base-related Revenues in

Base-related is indicated in blue, the total in purple. H9 indicates

Heisei 9, 1997. Source: Nago-shi Kikaku Soumubu Kikaku

Zaisei-ka (Financial Planning Section, Nago City Council).

Main projects funded by military base-related subsidies include:

- Shimada Commission projects: facility maintenance of

Meio University and theNeo Park International Species Protection Research Center - SACO-funded projects: construction of regional facilities such as community center buildings;

- Projects for the economic rejuvenation of the Northern region not classified as public works: i.e. facility maintenance of the ‘IT special zone’.

Since 1998, the growing share of revenue generated by subsidies linked to military bases has also increased total revenues. However, as the political motive that generated these subsidies ceases to exist, the revenue will disappear, and the quality of public services that residents receive – the most important public goods local government should provide – will deteriorate.

In 2001, with 9.1 billion yen coming from military base-related subsidies,

The City Council ostensibly aims at sound financial management, but so long as it pursues the immediate economic effects created by the new base, its financial position will only deteriorate.

Cabinet’s 2006 Decision: Determination to keep Okinawa a ‘

Of the governmental decisions made on Futenma relocation, Cabinet decisions have the greatest weight. On 30 May 2006, the decision made on ‘Government Initiatives for Restructuring US Forces in

1) the decision that the new Air Station would be partially opened for local commercial use and that a 15-year limit was to be imposed on

2) that a special economic rejuvenation scheme for the northern region was to be implemented.

Former Governor Inamine and Nago Mayor Kishimoto had insisted on the conditions under (1), among others, but now that Inamine has retired and Kishimoto is deceased, current political leaders are unlikely to bring them back to the negotiating table. Regarding (2), in 1999, the cabinet promised the then Governor that special subsidies were to be paid to northern municipalities irrespective of base construction. That promise has since been forgotten or ignored, and, once again, current local government is unlikely to demand subsidies for communities not involved in base relocation.

After 1999, the Cabinet Office promised special developmental support for the northern region. It was the only favourable term

Since the 1995 rape case, the Cabinet Chief has acted as de facto minister of Okinawan affairs, replacing the Okinawa Development Agency. In other words, the Cabinet Office has been in charge of all Okinawan special development projects and schemes, including the Shimada Commission Projects. In 2001, the Okinawa Development Agency was abolished and the new Ministry of Okinawa and Northern Territory Affairs, located within the Cabinet Office, took over. However, it was the Defence Agency that dominated the making of 2006 Cabinet decisions, over the Cabinet Office’s head. In January 2007, the Defence Agency was upgraded to become Ministry of Defence.

Historically, the Japanese institution that governs

Although Okinawan political leaders have been elected, promising economic development first and foremost, the economic development of

3. Henoko’s Geopolitical Location

Opposition protest is not the only reason why the construction of a new

What the

The oft-cited myth that

At the time of the Nago referendum in 1997, the new base was going to take the form of a removable marine heliport. In 1999, that was changed to a joint military-civilian ‘airport’. In 2006 the new base was further widened to require coastal landfill. In the 10 years of delay, the two governments have exponentially increased the capacity of the substitute air base.

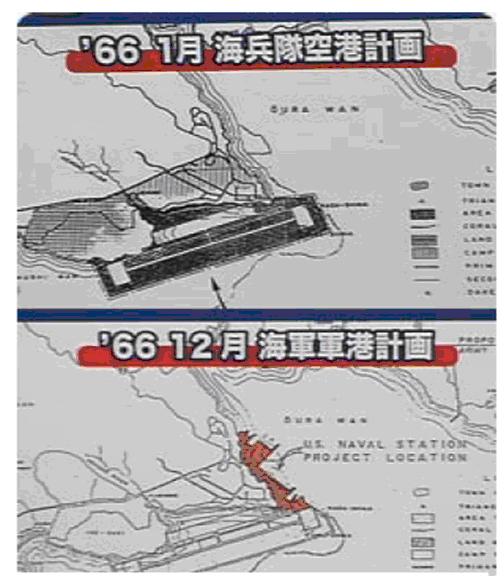

As reported by an Okinawan local TV network QAB, two plans were drawn up by the US Navy and the Marine Corps in 1966 for an airport in Henoko. Both included a berth adjacent to

Above: reproductions of two plans of an airport in Henoko/Oura Bay prepared by the US Marine Corps and Navy, in January and December, 1966. Source: QAB homepage

The planned construction site has grown much larger through the 10 years of delay. It is no longer a substitute for Futenma Air Station, but it now appears that Japan is constructing what the US military has wanted to build since the 1960s.[5]

The

How do the two governments justify the integration and reduction of US forces in

Since the initial

The overall view held by the government of

There are some obstacles to US military realignments in

1) any relocation of bases will meet with local resident opposition;

2) because the desired sites in the northern region are sparsely populated, relocation there would disturb the environment, including protected wildlife species.

In the absence of some other alternative,

What are the rationales for constructing the new base here? What are the compelling strategic reasons for limiting the relocation site of Futenma Air Station to

The puzzling thing is that the

· transferring 2,600 troops in total (800 artillery soldiers, 900 from the Marine regiment, 700 from transport and supply units, and 200 from supply units) from

· temporarily relocating the helicopter unit from Futenma to Kadena Air Base within 3 years.

Neither expanding the capacity nor relocating to another Okinawan location is essential to the Futenma closure. Why has there been such a strong push to build an upgraded

The answer probably includes many factors –

Conclusion: Reasons for Continued Resistance

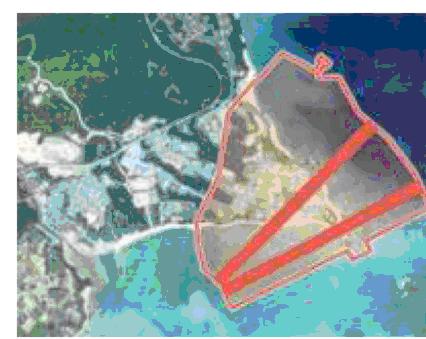

Finally, let me reflect on future public policy scenarios. The shape of the runway – whether the current V-shape plan is appropriate or not – is currently subject to negotiations between

Aerial projection of the V-shaped runway

After agreement is reached by the Prefecture and

1) Agreement on basic plan;

2) Environmental assessment (following the submission of a methodology report, investigations will be conducted and then a preliminary report will be submitted.)

3) Construction.

When the agreement on the basic plan is reached, the government will promptly commence the environmental assessment by issuing a methodology report. The residents are already familiar with the procedures and necessary action from the previous assessment procedures associated with the then plan for a civilian-military airport.

Environmental assessments in

Yet citizens’ groups have built networks that enable the mobilisation of international public opinion. Persistent campaigning and pressure for the cancellation of this project could change the situation. One citizens’ group has taken the case of excessive military presence and the abuse of Okinawans’ human rights to the UN. Their action may contribute to such change. There are multiple grounds on which citizens can mount public actions.

Thanks to the war against terror, it has become much easier for states to legally conduct themselves in ways that are immoral and authoritarian. It is an illusion that peaceful and free life can be enjoyed without strife.

The drilling investigation of the construction site in Henoko, necessary for environmental assessment, was blocked by determined citizen action. It would be impossible to expect a mass participation by ordinary citizens in another such dangerous blockade. Nevertheless, this kind of direct action is not the only method of civil resistance.

There are many tasks left for those of us who favour a robust civil society: creating multiple forms of resistance to the reckless projects of the government; inventing words that can communicate that such resistance is humanely sensible and reasonable; critically examining municipal and central government policy and formulating alternatives; producing case studies of autonomous economic development and implementing them.

Notes

[1] See, for example, Miyagi Yasuhiro (translated by Gavan McCormack) ‘Okinawa – Rising Magma’, Japan Focus, December 4, 2005.

[2] Kina Shokichi and Charles Douglas Lummis, Hansen heiwa no techou: anata shika dekinai atarashii koto (Anti-war and peace handbook: new things only you can do), 2006, Shuueisha Shinsho, 0334A, p18.

[3] Quoted from Chair’s comments from ‘The Report on the Advisory Panel’s Discussion at Initiating Commission on Okinawan Cities, Towns and Villages hosting US Bases’ See my (Miyagi) essay written in 2000, ‘Canary’s Song in a Coal Mine: A Critique of the Shimada Commission Projects’

[4] Henoko District, Henokoshi (History and Culture of Henoko), 2002, Henoko,

[5] See Makishi Yoshikazu (translated by Miyume Tanji), ‘US Dream Come True? The New

[6] Hisae Masahiko, Beigun Saihen (US Military Re-Alignment) Koudansha Gendai Shinsho, p 91

Miyagi Yasuhiro, born in Nago in northern Okinawa in 1959, was a central figure in the

This article was written for Japan Focus. Miyume Tanji is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Advanced Studies in Australia, Asia and the Pacific (CASAAP), Curtin University of Technology

Posted at Japan Focus on August 3, 2007.