Mission Impossible? Misawa as the Forward Staging Area for the Secret US-Japan Nuclear Deal and the Bombing of Iraq

Saito Mitsumasa

Translation by Kyoko Selden

A Misawa Base pilot is met by his family on his safe return. Capt. Tyler Young, 13th Fighter Squadron pilot, shares a laugh with his wife, Anna, and daughter, Clara, after returning from a deployment Aug. 20, 2009.

Global Strike

With a proud high-heel clatter not becoming a military runway, she rushes forward, followed by her children with slightly shy looks on their faces. A pilot in flight suit awaits them, arms spread. Embraces, kisses, tears. . . .

“So good you’re home.” “I missed you.” Many such warm words are exchanged making onlookers smile.

This was Misawa, the US Base in Aomori in northern Japan (home of the US Air Force’s 35th Fighter Wing) in October 2007, when the wind blowing ashore from the Pacific was turning cold.

The Misawa Base, the only Suppression of Enemy Air Defense (SEAD) unit of the US Pacific forces headquartered in Hawaii, is, so to speak, in the position of the first attacker of the entire force. It continually sends F-16CJ Fighting Falcons off to the Middle East. The above, then, should have been another commonplace scene. But something was different on that particular day. The welcome was more emphatic than usual, and the atmosphere on base appeared elated. This was the victorious return from the highest of Air Force missions. In August, two months before their return, the unit had successfully navigated the large-scale secret operation styled “global strike,” a “long-distance preemptive attack.”

F16-CJ

“4200 miles,” says a US military source I have before my eyes. Four F-16 combat planes that had been dispatched from the Misawa Base covered this tremendous distance flying non-stop to Iraq before flying from Baghdad to eastern Afghanistan, where they performed nighttime precision bombing raids.

Their target was the Taliban, the anti-government armed force in Afghanistan. Due to the nature of the secret mission, details remain unclear. But judging from available US military documents, the four planes had been dispatched as an American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) unit to the Balad Base in the suburbs of Baghdad, and, taking off from there, performed dispatched over twelve precision-guided bomb units called GBU-38s, each weighing 500 pounds.

The American Expeditionary Forces refers to deployment units, each with about 30 airplanes flexibly organized and including fighters and bombers, that the US Air Force deploys areas throughout the world. Since the Gulf War, they have been repeatedly dispatched to the Middle East, which is the world’s greatest powder magazine. In Iraq, they continue to operate long after the downfall of the Hussein administration.

SEAD has the role of leading the way in destroying antiaircraft missiles and important facilities like command headquarters. Misawa’s 35th Fighter Wing can be seen as the core of the Expeditionary Forces. Of the 40 airplanes based there, they continually dispatch approximately 10. Their F-16s were the first to attack Baghdad in the Iraq War (2003). At the time of the US-North Korea crisis (1994), on the brink of a second Korean War, F-16s were also dispatched to South Korea. These two examples help us clearly see the 35th Fighter Wing’s position.

The round trip between the Balad Base, SEAD’s Iraqi foothold, and the Taliban target amounted to 4,200 miles. The distance, exceeding that across North America, is impressive. But what is more remarkable about this bombing mission is that it was performed secretly and swiftly. It was only 18 hours from the drafting of the plan to the sortie.

What is more important is that those F-16s belonged to an American base in Japan, far from the Middle East, and the Japanese people had no idea that the attack was indirectly launched from their soil until I exposed this fact in Shūkan Kinyōbi, (Sept 5, 2008, pp. 16-19). They were intentionally kept in the dark about the fact that Japan was indirectly involved in the strategic cleanup operation of the guerillas in Afghanistan.

“The 500-pound precision munitions scored direct hits. The pilots became fond of the sky above eastern Afghanistan.”

This is how a US military source records the achievement of the bombings. Perhaps because the operation was successful, this even conveys uniquely American humor.

The four airplanes spent 11 hours for the roundtrip flight. Receiving air-to-air refueling as many as thirteen times, they flew over six countries en route. Their flight path is a mystery, but surely this was a mission challenging the endurance of the aircraft and pilots. In a sense it can be said to have been a calculated “adventure.”

The global strike concept apparently enjoyed the powerful support of Bush’s Secretary of the State Rice. The strategic concept is to “be prepared to attack any place in the world within 24 hours.” One application of global strike was this secret operation. The US is, moreover, constructing a system by which it can instantly attack any place in Middle East from Iraq.

Why, then, was it necessary to go to that extent to bomb Afghanistan? Why didn’t they use large-model bombers? Is the Taliban that much of a threat?

Numerous questions arise about this operation. To these, Japanese and US military specialists respond alike. “It is highly probable” they say, “that this was a rehearsal for an assumed attack on Iran’s nuclear complex, which is moving ahead in defiance of the US.”

The specialists take note of the situation in which Iran is central to the US gaze as their greatest assumed enemy along with North Korea.

The reason that Misawa’s F-16s were chosen to perform the operation is simple. To borrow the words of Niihara Akiharu, an international relations researcher conversant with US-Japan military relations, “It’s simply that even the US Air Force, which is at the highest level in the world, has a limited number of units that can perform the extremely specialized mission of nighttime, super long-distance, precision bombing, and one of them is at Misawa.”

The true picture of Misawa revealed

The Misawa Base is hard at work fulfilling its special duties. But this singularity of Misawa is nothing new. It goes back to the mid 1950s at the peak of the east-west cold war.

At the time, anticipating that “the next war would be a nuclear war,” the US and the Soviet Union fiercely competed in nuclear development. In that framework, the mission assigned to Misawa, the northernmost and largest US air base on the Japanese archipelago, was precisely to carry out nuclear attacks using airplanes to target the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea. Misawa was positioned as a base for nuclear sorties in World War III to come.

In order to penetrate this nuclear mystery, starting in 1998 I began examining, US Air Force secret documents. I took aim at the “command history” of generations of units stationed at Misawa.

Negotiating with The Air Force Historical Research Agency in Alabama, after lengthy negotiations I obtained a 4,000 page document. As expected, every cover was stamped “SECRET,” and the portions that I really wanted to see were blacked out. Still, I had no choice but to go forward. I struggled with the document for two years, collected evidence from testimonies by former pilots, and gained a clear picture of cold war era Misawa. That true picture was namely the role of US air bases in Japan in the swift execution of nuclear war.

The document states directly: The duty of the 39th Air Division (the unit then stationed in Misawa) is to execute Emergency War Plans (EWP) in the event of a hostile action against the United States and its allies (1961).

EWP is a US Air Force manual drafted on the assumption of entering a total nuclear war. The document uses a roundabout expression, “is in execution of EWP,” but, simply put, it asserts that Misawa’s main duty is to conduct nuclear operations. The document lists the special powers of the Misawa commander to carry out EWP:

1. Start alerts for nuclear-loadable units.

2. Load nuclear-loadable aircraft with nuclear weapons.

3. Start pre-planned nuclear attacks in the event that a world war erupts.

I cannot forget the shock I experienced when I saw the expressions “nuclear-loadable” and “nuclear attack,” standing side by side as a matter of fact. They plainly indicated that Misawa during the cold war era was a base with a nuclear attack mission.

What then was the nuclear bomb to be used according to the plan? It was a small strategic nuclear weapon that could be loaded on a one person jet fighter. The US military had in mind the MK7 (70 kiloton), whose explosive power was five times greater than the atomic bomb of the Hiroshima type. This was the world’s first practical nuclear bomb that began to be deployed in 1952.

MK7

Later, it escalated to a hydrogen bomb called MK28 (deployed in 1958), then MK43 (deployed in 1961) with an explosive power of 1 megaton or 70 times greater than the Hiroshima-type bomb, and finally B61 (deployed in 1968) and still in service.

In case of emergency, all combat bombers of the two flying corps (40 planes) positioned in Misawa were to set off, each with such a bomb.

The targets were the Maritime Province of Siberia around Vladivostok, Northeast China such as Dalian and Lüshun, and North Korea where the fires of war still burned.

Nuclear attack missions and US military bases in Japan

What is startling is the discovery that many such nuclear attacks presupposed kamikaze-like “one-way attacks.”

Aircraft deployed in Misawa in the 1950s were the F-84 G Thunderjet and F-100 D Super Sabre, three and two generations previous to the F-16 respectively. Both had a combat radius of approximately 625 miles, but the target assigned to pilots exceeded that distance in many cases. They would be unable to return to Misawa, where their wives and children waited. Former Major Francis Loftus (Texas), a pilot who worked at Misawa then, told me about this tragic situation with a grave expression on his face.

“It was very stern duty. The smallest error would blow it. If I actually made a sortie, I thought, I would probably fall into the sea, because, depending on the target, it was impossible to return to the base.

Both the Soviet Union and China must have known that Misawa was a nuclear attack base. So, I didn’t worry too much about the potential one-way trip. If a nuclear war started, Misawa would receive nuclear attacks, and there would be no place for me to return to. Should I survive my attack mission, I thought I might have to make an emergency landing somewhere and perhaps commit suicide. I was equipped with potassium cyanide for that purpose. . . .”

Concerning specific targets assigned to pilots, former Col. George Barnart (Texas), who worked at Misawa’s command unit in those days, testifies that “in order to completely block enemy counterattack, we would have had to destroy the airport, the missile site, the command unit, and communication facilities, which naturally included the storehouse for nuclear weapons.”

In order to attack their nuclear targets with precision, young pilots in their twenties repeated strenuous drills at Amagamori shooting range to the north of the Misawa Base, that consisted of flying low at a fierce speed of 500 knots (approximately 560 miles per hour) 50 feet above the ground—low enough to almost touch electric lines—and deliver a nuclear bomb.

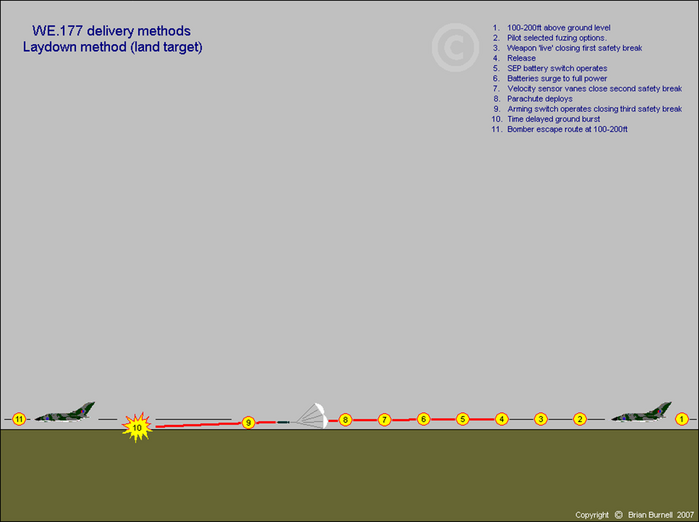

Over-the-shoulder, laydown, retarded. . . . Delivery methods changed rapidly accompanying the progress of nuclear technology, but one thing did not change: the low-altitude, high-speed, life-risking acrobatic flights.

Over-the-Shoulder Method

Laydown Method

Copyright Brian Burnell © 2007

Former Major Loftus explains the over-the-shoulder method, which was the earliest delivery method used:

“The cockpit was equipped with a special G meter, and, when releasing a nuclear bomb to the target, the pilot had to loop the loop exactly at the gravity of 4G and at an angle of 104.5 degrees. And within 45 to 60 seconds following the release you were expected to accelerate with the afterburner to get away at the speed of sound.”

As he said, the majority of the drills at Misawa involved practicing nuclear bomb delivery. Repeated training was indispensable for attaining the advanced, complicated skills that were required. The secret document shows that one flight corps dropped as many as 540 mock nuclear bombs within half a year. This translates to over 1,000 per year. Because 2 flying corps were stationed at Misawa in those days, it follows that over 2,000 mock nuclear bombs were being consumed per year at this base alone. The document eloquently narrates how “nuclear-steeped” we were then.

The severe drills naturally produced many victims. My survey reveals that 6 F-100s fell in just two years starting in September 1961, when the training was most intense. “There were almost more deaths than in the Vietnam war” (former Major Raymond Tiffault, South Carolina). In that sense, the Amagamori firing range can be called the grave marker for the young pilots who sacrificed themselves to the cold war.

The secret document made clear that nuclear attack missions were also assigned to bases other than Misawa. They were Iruma in Saitama prefecture (the 3rd Bomber Wing), Itazuke in Fukuoka prefecture (the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing), Komaki in Aichi prefecture (the 9th Fighter-Bomber Group), and Kadena in Okinawa prefecture (the 18th Tactical Fighter Wing), the last of which was under the US military rule until its repatriation to Japanese rule in 1972.

B-57 Canberra light bombers were deployed at Iruma, and, as at Misawa, F-84 and F-100 fighter-bombers at Itazuke, Komaki, and Kadena. Nuclear delivery drills for Iruma Base pilots were mostly conducted at the Mito firing range in Ibaraki prefecture, but at times the locale changed to Amagamori range.

These four were the nuclear sortie bases that I was able to confirm in the secret document. But I know from circumstantial evidence and testimonies that the probability is quite high that Yokota, Tokyo, was another such base. At present, Fifth Air Force headquarters, which also serves as the headquarters of US military forces in Japan, is located at Yokota. In other words, nearly all US air bases on the archipelago were turned into nuclear bases.

Loopholes for bringing in nuclear weapons

Here’s the greatest riddle regarding nuclear weapons in US military bases in Japan: when did the nuclear missions begin and when did they end?

It is known that at least Misawa and Komaki were already so assigned in 1957. This would mean that the entire archipelago was capable of nuclear departures for fifteen years until 1972, when Okinawa was returned to Japan “nuclear-free.”

Another question surfaces here. It’s simple: didn’t Japan have the three non-nuclear principles, which means that we do not let others bring in nuclear weapons? In fact, therein lay the clever trick fabricated by the US military and the Japanese government.

What Misawa and other departure bases were always equipped with were “components” without nuclear fuel. “Cores” were to be carried in at the last minute from Kadena that was under US military rule on Okinawa. “As long as components were not loaded with nuclear fuel, nuclear bombs were not present”—this was the US logic. In other words, the three non-nuclear principles had been reduced to mere form.

There was one other loophole. It relates to US-Japan interpretation of the term “introduction,” which corresponds to the Japanese mochikomasezu (let no one bring in). Gabe Masaaki of Ryūkyū University (international relations) clarified this “secret agreement” between the two countries. He explains the dexterity of this loophole as follows:

The US used the term “introduction” in the sense of “storing” or “deployment” on land. From this interpretation, temporary passing of an aircraft or temporary stopping at a port by a ship was no more than “transit.” This is not included in “introduction.” In other words, even if aircraft or ships loaded with nuclear weapons enter Japan’s territorial airspace or waters, it does not mean “bringing in.” This was an item of agreement confirmed at a 1963 closed meeting of Ambassador Reischauer and Foreign Minister Ōhira.1

There is a military term DEFCON, short for defense condition. It defines five levels of military readiness from standard peaceful condition, which is 5, to expectation of imminent attack, which is 1. According to the secret document, as soon as DEFCON 2 was declared, meaning heightened force readiness just below maximum readiness, C-130 Hercules, a transport aircraft code-named “High Gear,” was to set out with nuclear “cores” hoarded in Kadena’s nuclear storage.

C-130 Hercules

The cores, the size of a tennis ball and each nestled in a container called a “bird cage,” were to be transported along with military technicians who are nuclear weapons specialists to nuclear sortie bases including Misawa, Komaki, Itazuke, and Iruma, to fit the “components” loaded under the body of fighter-bombers preparing to take off.

All standby fighter bombers and light bombers were required to be ready to take off within 30 minutes following DEFCON 1 regulations. The bodies of nuclear weapons without cores were kept at special facilities called TOF (theatre operation facility) near runways.

The US classified this nuclear transport to mainland Japan, intended for total war, as “transits” for “temporarily carrying, fitting, and sending out again,” not “bringing in” nuclear weapons.

In other words, such US military bases as Misawa, Komaki, Itazuke, and Iruma confronted the Soviet Union, China, and Korea, nearly freely without the restriction of the three non-nuclear principles. Japanese citizens remained ignorant of this imminent nuclear crisis while providing bases for the American forces. As with the secret Afghanistan operations mentioned above, merciless American military strategies are glimpsed here.

An empty nuclear agreement

The secret nuclear agreement, by which generations of administrations tacitly permitted ships loaded with nuclear weapons to pass through Japan’s territorial waters and stop at ports, has become a large political issue. Its focus is “bringing in nuclear weapons” by aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and so forth. But the Air Force’s nuclear weapons similarly travel freely, and it is an established fact that they would be put to practical use in time of emergency—in “secret agreement” form.

Prime Minister Hatoyama states of the secret agreement that he will “conduct a thorough investigation and publicize the results.” Whether the public investigation will cover not just “nuclear weapons at sea” but the “nuclear weapons in air space” that I have researched, and whether the “secret agreement” policy to keep the people ignorant will in fact be exposed in broad daylight—how the new administration will handle this remains to be seen.

There was a blank spot impossible to grasp in the process of clarifying nuclear-loaded sorties by the US military in Japan. That was the location of Kadena’s “nuclear storage space” that was the source of “core” supply for air bases in mainland Japan. It was in 2005 that I was able to locate the place, seven years after I obtained the secret document. I was finally able to collect evidence from a 1973 aerial photograph, right after reversion, together with testimonies of Japanese civilian employees from those days. It was in a corner in the hilly areas adjacent to the eastern tip of Kadena’s runway.

The “nuclear storage space” concealed in darkness for half a century existed at the entrance of the powder magazine just one road (the present-day prefectural highway 74) away from the airport. So close to the runway—this was unexpected.

Tomoyose Chōei (deceased; Ginowan city, Okinawa prefecture), who had access to the “nuclear storage space” in those days as a civilian employee of the company of engineers attests to the veracity of that space being a “special place”: “In the spacious Kadena powder magazine, military men in nuclear protective clothing were around in that corner alone. The complex proper was deep down, sixth stories underground. When entering there we were required to wear a film badge that would confirm exposure to radiation.” He continued:

“It was a special area under unusually heavy guard, where even military police could not enter. So there was a tacit understanding among us that it was a nuclear storage space. Those concerned all knew about it.”

According to the secret document, the complete nuclear war plan anticipated that the Pacific forces would use a total of 421 cores. It is natural to consider that at least more than 200 of them were kept in this “nuclear storage space.” Of these, 50 were assigned to Misawa—this is my conclusion.

US strategies that transcend the US-Japan Security Treaty

The strategy replacing this nuclear sortie plan is precisely the “global strike” approach. Its trump card is the fully high-tech precision guided missile called GBU-38.

GBU-38 is a new-generation bomb called JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munitions). It combines GPS (Global Positioning System) and Inertial Measurement Unit, thereby enabling pin-point attacks. It also has the characteristic of a Massive Ordnance Penetrator. In other words, it is a special weapon intended for destruction of military facilities like the headquarters and ballistic missile bases protected by solid rock as hard as tortoise shells or hidden underground.

GBU-38s

This weapon was first made public in Japan in September 2005 at the Misawa AB Air Festival. The moment I saw the dark green special bomb, matter-of-factly displayed in a corner of the hangar, I had a presentiment that Misawa, now having obtained new power, would greatly enhance the ability for air attacks to become one of the world’s most powerful attacking divisions.

That presentiment came to fruition in the form of the secret Afghanistan operations.

Misawa’s F-16 does not formally appear in the 2006 road map for the US military transformation, but there is no doubt that it is a special trump card.

Misawa emerges afresh, as do the roles of other US military bases, through the new US military strategy called “global strike.” Niihara plainly and sharply analyzes this:

“What became clear from the secret Afghanistan operations is the surpassing role of Misawa, or by extension the US military bases in Japan. To position precious units capable of handling such difficult missions in the safe, rear area of Japan, and repeat drills that approximate actual combat, then send them unhesitatingly to the front when necessary—this American way of thinking about their bases in Japan can be said to have been made clear through these secret operations. That puts into relief the new positioning and special character of the US bases in Japan within the framework of the transformation. It clearly indicates that the radius of Misawa’s operations covers all Asia.”

This means that the Japanese archipelago, while it is a rear support foothold for the US military, continues to be a powerful departure point even after the conclusion of the cold war.

James Przystup of National Defense University, a specialist on US-Japan security relations I met during data collecting in the US, told me about the projected transformation of the US military in Japan: “Japan will, as it did in the past, continue to play a central role in American strategies. Its weight will increase further. Starting with the US military transformation, the US-Japan alliance is about to become something that covers not just Asia but the entire world.”

“Japan” in this statement can be replaced by “US bases in Japan,” and further by “Misawa.” Namely, by obtaining the new strategic power of destruction called “global strike,” Misawa is extending its range of activity beyond northeast Asia to all Asia. Needless to say, it not only includes Afghanistan, where chaos is deepening, but North Korea and Iran. The latter two being areas where Chinese and Russian interests clash with those of the United States.

What further requires attention is the wishful catch phrase, “Japan as Asia’s England,” repeated unanimously by top-level members of the Department of Defense I interviewed. What they envision is a “Japan-US-England triple alliance” with the US at the center.

This vision of the Pentagon is easy to grasp if we look at the map of the world from the US perspective. The idea is two-sided operations, in which forces will move from American bases in England to conflicts in Europe and Africa, and from American bases in Japan to emergencies in Asian areas including the Middle East.

In other words, it is a grand conception of world management: splitting the globe into halves with the US as the axis, it will manage the right half using England as a foothold and the left half using Japan as a foothold. This is the ambition of the US that is trying to be today’s Roman Empire, that is, Pax Americana, a world order dominated by the US.

Unaware of this, Japan is becoming one of the two strategic footholds the US regards as most important in global perspective.

Japan as a strategic foothold in this American scheme, however, poses a great potential problem: a possible conflict with the Far East provision of the US-Japan security relationship. The fundamental question is whether strategic operations like “global strike” that span the world may contravene the US-Japan Security Treaty’s provision that limits the use of American bases in Japan to “contributing to the security of Japan and the maintenance of international peace and security in the Far East.”

The Far East provision is like a fetter, so to speak, limiting the use of American bases in Japan. Generally, the scope is understood to be “Northeast Asia north of the Philippines.” Misawa’s F-16s, in going into action in the Middle East, stray far beyond this scope. The Japanese government’s view is that, because they use Iraq as the foothold for their actions, they don’t count as direct sorties from Japan, and thus don’t contravene the Fast East provision.

The government’s forced interpretation naturally produces many frictions. Lecturer Iijima Shigeaki of Nagoya Gakuin University (Constitution and peace studies) poses questions from the viewpoint of the Japanese Constitution:

“The American military in Japan exists only for the sake of protecting security of the Far East. Therefore, the fact itself that Misawa’s F-16s are flying over Iraq and Afghanistan faraway from Japan is a problem, to say nothing of global strike that has the entire world in its field of vision. It goes against the idea of the current Peace Constitution, and it is also counter to the Far East provision.”

Hirata Hisanori, an energetic journalist specializing in US-Japan security policies, takes seriously the fact that Misawa is positioned as the vanguard of global strike and that F-16s start out from Japan. His logic is extremely clear as he relates it to refueling activities upon the Indian Ocean, which the new Democratic administration considered “an urgent issue to be solved.”2

“Looked at from present warfare in which no distinction exists between the front and rear and, moreover, supply holds the key to victory or defeat, refueling that the Marine Self-Defense Forces are conducting now is nothing less than ‘participation in a war.’ Much more so with F-16s stationed in Misawa, which repeat fierce attack drills and make indirect sorties to areas involved in disputes. In the sense that Japan directly assists the American forces’ ‘attacks,’ this bears a heavier meaning than refueling activities.”

Hirata also raises another issue: “Despite the fact that Japan strongly supports the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the majority of Japanese citizens are unaware of this. I think that may be because they don’t fully understand the meaning of having US bases and supporting the US military.”

The high-tech bomb, GBU-38

The New Yorker shockingly reported in 2007 that war with Iran was imminent, saying that the American military had installed a special team within the Joint Chiefs of Staff for deciding on a plan to attack Iran, and that, pending the President’s approval, the plan could be enacted within 24 hours.

Plans to attack Iran reported by the American media share one common theme. They list nuclear facilities as in Natanz and Isfahan in central Iran as major targets. Natanz is a uranium enrichment complex indispensable to production of nuclear weapons and Isfahan is a uranium converter complex and a tunnel for underground experiments. All these facilities are constructed over 25 meters below ground.

On the other hand, since the 1950s, training for attack has assumed North Korea to be the sole hypothetical enemy. Following North Korea’s withdrawal in 1993 from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, the targets are said to have fixed on the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center and such intermediate and long-range nuclear ballistic missiles as the Nodong and Taepodong. These facilities are located in rocky mountains like “Thunderbird Secret Base.” I would like the reader to recall the secret Afghanistan operations once again. The target was a large underground complex of the antigovernment power, and the weapon that targeted it was the bunker buster GBU-38.

In fact there was an incident related to the GBU-38 in late July 2009. The Stars and Stripes, a quasi-official newspaper of the US Department of Defense, reported on a successful F-16 test using mock bombs at Misawa.

Once when I published a photo of the GBU-38 in a newspaper, I was sharply questioned by the US military about where I had photographed it and whether I had obtained permission to do so. Aside from this, I was in constant trouble with the US military about material gathering, and I even had the “honor,” first of its kind in this country, of being forbidden to enter bases. This is a digression, but the report finally highlighted this well-protected high-tech weapon.

The article reports that training in the test delivery of a mock missile, accompanied by the introduction of a computer program that analyzes the planned delivery area, had until then been possible only in the States with its spacious land areas, but that it had now become possible in Japan, limited to Misawa’s Amagamori firing range. The range is the “nuclear grave marker,” where delivery training of mock nuclear bombs was conducted until the early 1970s. At the identical site, this time today’s strategic weapon, the GBU-38, was deployed in mock missile delivery training.

Interestingly, a top-level Misawa base leader, responding to a Tōō Nippō interview, stated that the Marine Corps and Navy aircraft at Iwakuni (Yamaguchi prefecture) and Atsugi (Kanagawa prefecture) may, in the future, be able to deliver mock missiles at Misawa.

Accompanying the transformation project of the US military in Japan and starting in 2007, Misawa has been hosting aerial training for US bases throughout the country. This means that it is highly likely that, in the future, delivery training for GBU-38s will center on Misawa. The one-time “nuclear grave marker” may become the “sanctuary” of high-tech weapons. Misawa is beginning to flaunt the possession of GBU-31s, four times larger than GBU-38s and highly destructive (2,000 pounds). This is ominous.

GBU-31

Iran in a touch-and-go situation and North Korea

In early September of 2009, North Korea claimed that plutonium extracted during the resumed operation of its nuclear facilities had been weaponized. On October 12, they launched five short-range ballistic missiles in succession. As if in concert, Iran announced that its uranium enrichment activities were going well at the Natanz nuclear complex, and plunged into a demonstrative act of test launching the newest model middle-range ballistic missiles Shahab-3 and Sajil.

This was a hard-line stance that could be interpreted as a challenge to the US, which dominates the world as the single super power. President Obama responded to this with a threat that the US will not preclude any options (including military actions). Mohamed ElBaradei, the then Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) who stood between them, commented that the situation around Iran’s and North Korea’s nuclear development had reached an impasse.

Iran in a crisis, and the North Korean situation—will an Iran War or a Second Korean War occur? The only thing we can say is that, one day, Misawa’s F-16s, with a star on each wing and carrying a precision guided bomb, may be flying over the nuclear complexes and ballistic missile bases of Iran and North Korea.

This is part one of a serialized reportage titled “Shimokita Nuclear Peninsula” (Shimokita kaku-hantō 下北核半島) by Kamata Satoshi and Saitō Mitsumasa, published in the January issue of Sekai.

Saitō Mitsumasa is an editorial committee member of the Tōō Daily (Tōō Nippō 東奥日報) of Aomori City. He specializes in the movements of the US military. Saitō is the author of Misawa, the “Secret”American Base (Beigun “himitsu” kichi Misawa 米軍「秘密」基地ミサワ) and The Frontlines of American Forces in Japan (Zainichi Beigun saizensen 在日米軍最前線). He is a recipient of the Ishibashi Tanzan Prize.

Kyoko Selden, the translator of The Atomic Bomb: Voices From Hiroshima and Nagasaki and other works, is an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. She translated this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Saitō Mitsumasa, “Mission Impossible? Misawa as the Forward Staging Area for the Secret US-Japan Nuclear Deal and the Bombing of Iraq,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 10-2-10, March 8, 2010.

Translator’s Notes

1 See Steve Rabson, “Secret” 1965 Memo Reveals Plans to Keep Nuclear Weapons Options in Okinawa After Reversion.

2 The activities were terminated on January 16, 2010, when the special measures law lost effect and was not renewed.