Michael Penn

In late October 2007 an odd story appeared in the press. A Japanese-owned chemical tanker called the Golden Nori was hijacked off the coast of Somalia. There were no Japanese nationals on board, but the East Asian nation had become entangled, quite unusually, in an East African affair. Unforeseen at that time was that this curious incident would eventually become one of the top foreign policy issues in Tokyo: Somali piracy has emerged as a potential turning point for Article Nine of the Japanese Constitution, and is significant for other reasons as well. The following essay reviews the record of Japanese encounters with Somali pirates and explores the motives and political pressures driving the Maritime Self-Defense Forces (MSDF) toward a proactive role in suppressing East African piracy.

Attacks on Japanese Shipping

At this writing, a total of seven ships of Japanese affiliation have run afoul of Somali pirates. The Golden Nori affair was the only case that occurred in 2007. After a period of negotiations and, apparently, the payment of a substantial ransom, the ship was released in December of that year. That appeared to be the end of the story.

However, in April 2008 an apparently-unrelated news story appeared about a rocket attack on a Japanese oil tanker named the Takayama off the coast of Yemen. The captain and a portion of the crew were Japanese nationals. The rocket blast created a small hole in the stern that caused fuel to leak, but did not harm any of the crew or seriously cripple the tanker. The ship was able to continue its journey without further event.

It was the second half of 2008 that witnessed the acceleration of the crisis. No less than five ships with some affiliation to Japan were captured by Somali pirates. The Japanese-owned Stella Maris and MT Stolt Valor, as well as the Japanese-operated Irene and African Sanderling were seized, ransoms paid, and later released. The Japanese-owned Chemstar Venus and its crew remain in pirate hands as of this writing. None of these ships had any Japanese crew members—most of the crews are Filipino—but the epidemic of East African piracy has unnerved Japanese shipping companies.

Somali pirates

Somali pirates

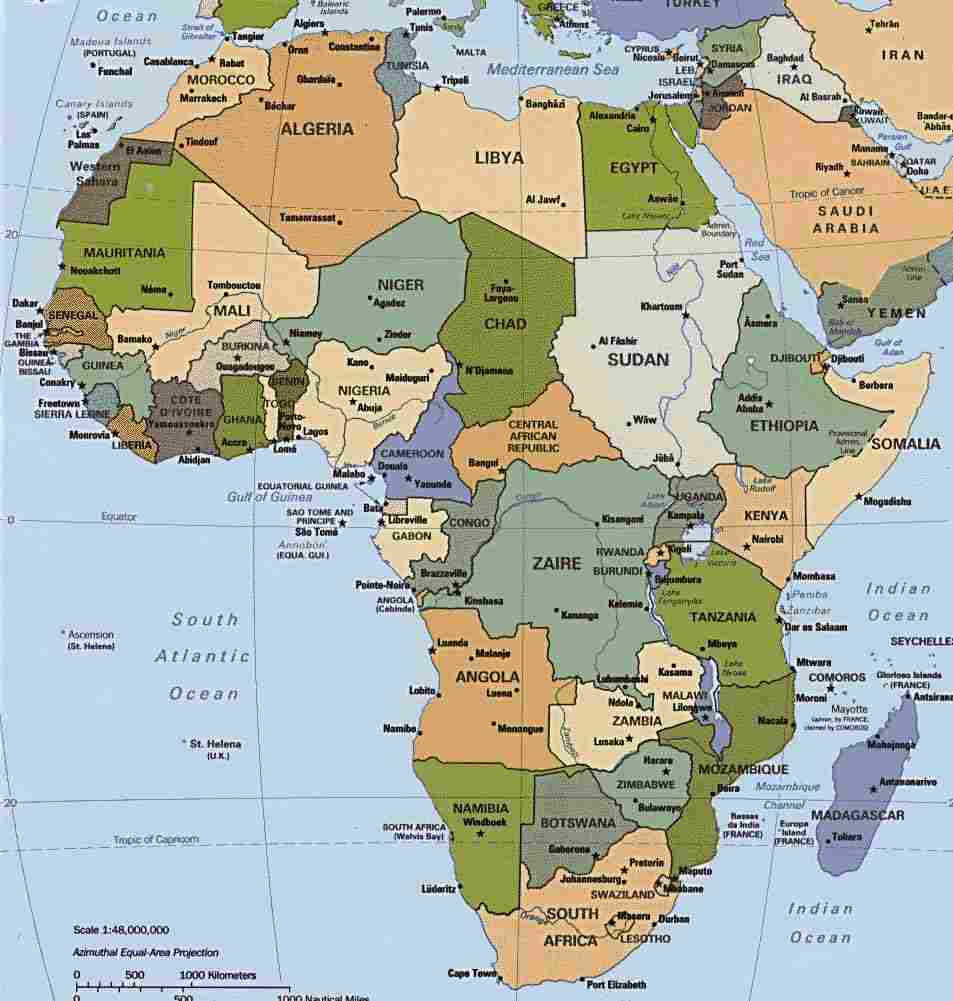

The Asahi Shinbun has reported that Japanese shipping companies began in the autumn of 2008 to reroute some vessels around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and avoid the more direct route through the Suez Canal. This longer route adds six to ten days to the journey, and may cost Japanese shipping companies, collectively, an annual US$100 million in additional expenses. [1] Ordinarily, Japanese companies send about two thousand ships through the Suez Canal on an annual basis, which would mean that about five or six Japan-affiliated ships pass through the Bab al-Mandab—the “Gate of Tears,” the straits separating East Africa from Yemen—on any given day.

The Origins of Contemporary Somali Piracy

One question that few in Tokyo seem to be asking is why this piracy has suddenly reached epidemic proportions along the Somali coast. Like most governments and observers, Japanese government leaders have denounced the pirates as representing a grave threat to international order without stopping to consider the reasons why this problem emerged in the first place. Perhaps this lack of curiosity reflects a simple deficit of imagination; or perhaps it may be that the answers to be found do not reflect very well on the developed world.

Since the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu which resulted in the deaths of nineteen US soldiers (the famous Black Hawk Down incident), the West has more-or-less washed its hands of the anarchy and suffering of the Somali people. So long as they confined themselves to killing each other in their remote East African nation, no one in major capitals really gave much thought to Somali interests.

Smaller-scale piracy has always been known along the Somali coast, but in 2006 the practice was nearly eliminated by the rise of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). The ICU cracked down on the pirates and came close to reunifying and bringing peace to the war-torn nation. The ICU failed in this endeavor because of the combined interventions of Ethiopia, which invaded Somalia with its land forces, and the United States, which began funneling support to the old Somali warlords, now calling themselves the “Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism.” Both Addis Ababa and Washington intervened because they shared the fear that the establishment of the ICU would be a key victory for “Islamic radicalism” and might serve as a potential base for Al-Qaida. Ethiopian leaders also faced the additional problem of Somali separatist forces operating within the Ogaden region along the border with Somalia.

Militia from the Islamic Courts Union

Militia from the Islamic Courts Union

Aside from plunging the Somali people back into their long war, the Ethiopian and American interventions also allowed the piracy problem to reach its current proportions. Some of the same warlords that have received US support for their anti-ICU credentials also seem to be playing a low-key role in letting the pirates carry out their activities. The government of Eritrea, which supports the ICU, has explicitly blamed Washington for the piracy problem. In a November 2008 statement, Asmara charged:

The main cause of this problem is the vacuum that has been created for the last seventeen years in Somalia. Sadly, an enduring solution is not conceivable until the reckless acts of the US and its surrogates aimed at balkanizing Somalia, dividing its people along ethnic and clan lines… cease. The solution lies, accordingly, in the liberation and reconstitution of a united and sovereign Somalia. Unless and until the entire Somali people—whether they are in the so-called ‘Somaliland,’ ‘Puntland,’ ‘Jubaland,’ or ‘Benadirland’—extricate themselves from the malaise of fragmentation to bring about their own enduring solution by themselves, piracy and other deplorable activities will not indeed cease. [2]

Aside from the larger issue of a comprehensive political settlement for the Somali people, there are deeper issues related to the appearance of the pirates themselves. The ‘muscle’ of the pirates is believed to be provided by former militiamen who have taken their land-fighting out to the seas. On the other hand, the nautical expertise is being provided by former fishermen who are now out of regular work.

And why are Somali fishermen out of work? The Somali pirates themselves have alleged that international businesses have depleted the fish stocks in Somali territorial waters; moreover, toxic wastes have been dumped along the Somali coasts by foreign agents who understand well that there is no central government in Somalia to protect the nation’s legal rights. [3] Januna Ali Jama, a spokesman for the Somali pirates, justified their actions in September 2008 in the following terms: “I do not think we are in the wrong. Our country is destroyed by foreigners who dump toxic waste at our shores.” [4]

It is difficult to fully evaluate these claims from long distance, but it does seem problematic that most analyses of the problem of Somali piracy conceive of the issue only in narrow military terms and securing sea lanes rather than examining more comprehensively how the problem came about, and what Somali perspectives on the issue might be. In the context of Japanese policy in particular, it should be kept firmly in mind that we are talking about a long-distance conflict between a Somali people with an estimated per capita annual income of US$600 and a Japanese people with an estimated per capita annual income of US$33,500. [5]

Political Winds Driving Tokyo Forward

Reports emerged in the last week of 2008 that Tokyo was preparing to send MSDF destroyers to protect shipping along the Somali coast. The bill which is being prepared by the government is likely to allow the most permissive rules of engagement that the MSDF has ever had, which means that they may be authorized to shoot and kill for the very first time in their organizational history which dates to 1954. The bill may state that Japanese sailors can employ deadly force even if they are not under direct attack from the pirates. The bill may also provide for close cooperation between the MSDF and the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) since the Japanese military is not authorized to make arrests. Theoretically, the new framework could provide for MSDF destroyers to battle with pirates along the coast of East Africa, kill some of them in the fighting, and bring captives back to Japan for prosecution. [6] The exact terms of the bill, however, are still under negotiation. The government is, moreover, also mulling the possibility of sending the MSDF even in the absence of a new law by “reinterpreting” older laws. [7]

Clearly, if events transpire in a manner similar to the picture being painted above, this will mark a major departure from past Japanese international behavior. What factors are driving these changes? We will suggest six:

1. Justifying the Extension of the Indian Ocean Mission

2. Demonstrating Japan’s International Security Contribution

3. Utilizing the Japanese Navy

4. Keeping Up with the Chinese

5. Connecting with Yemen

6. Dividing the Political Opposition

Each of these motives will now be explained.

1. Justifying the Extension of the Indian Ocean Mission

For the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its coalition ally New Komeito the emergence of the piracy problem came at a politically convenient time. Since the resounding victory of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in the July 2007 House of Councillors election, the government has been under a withering political assault from the opposition parties demanding that several SDF missions abroad be ended. None of these struggles was fiercer than the MSDF Indian Ocean mission battle of late 2007. In order to achieve the results they desired, the ruling parties resorted to the highly questionable tactic of employing their Koizumi-era supermajority in the House of Representatives to override a decision of the upper house. This was the first time such a thing had been done in about half a century, and it was done in defiance of public opinion.

By the summer of 2008, a new battle on this very same question was shaping up. The government wanted to authorize yet another year-long extension of the MSDF mission. For the ruling parties, the intensification of Somali piracy at just that time was fortuitous. As early as August, then-LDP Secretary-General Aso Taro was among those darkly hinting that Japan’s vital sea lanes would be in danger if the MSDF were absent from the Indian Ocean: “I want the public to realize we cannot close our eyes and expect others to do Japan’s work when 90% of the oil is brought into Japan through the Indian Ocean.” Aso quickly linked this concern to the issue of Somali piracy, and the editors of the Yomiuri Shinbun in particular, starting in August and continuing up to the current day, agitated relentlessly for the MSDF to be re-tasked to take on Somali pirates.

In fact, the MSDF Indian Ocean mission appears to have nothing to do with anti-piracy efforts (it would be a violation of the existing law if they did have a role), but this argument was probably marginally useful in reducing opposition to the extension of the mission. The fact that the Horn of Africa lies rather distant from the main oil route between the Persian Gulf and Japan did not, as far as we know, lead Japanese opponents to challenge LDP Secretary-General Aso’s suggestions.

Curious logic and fuzzy geography aside, a fresh one-year extension of the MSDF Indian Ocean mission was indeed forced through the Diet in mid-December 2008, and this particular rationale lost most of its saliency. It did, however, put the issue of Somali piracy closer to the center of the Japanese foreign policy debate than would have otherwise been the case.

2. Demonstrating Japan’s International Security Contribution

One of the arguments repeatedly advanced by the editors of the Yomiuri Shinbun editorial page—and many leading conservative politicians as well—is that Japan must enhance its efforts to make “international contributions.” Since the Persian Gulf War of 1991 there have been mounting pressures to make these international contributions in a military form. As a Yomiuri editorial put it on December 27, 2008: “To fulfill its international responsibilities, Japan must consider various possible measures.”

This Japanese view, of course, has been strongly encouraged, and to a significant degree orchestrated, by US officials. Most recently, US Ambassador Thomas Schieffer commented: “I hope Japan will make a contribution and will do more to help rid the world of this scourge of piracy that we’re experiencing now.” [8]

Japanese conservatives are vulnerable to such appeals for reasons of vanity as well as for practical reasons. The desire for enhanced prestige has been a consistent theme in modern Japanese foreign policy. Okamoto Yukio once wrote that, “In its relationship with the United States, Japan has craved respect.” [9] Kenneth Pyle has identified this quality as “honorific nationalism.” [10] My own preferred term is “prestige diplomacy.” But whatever the precise designation, it signifies that Japanese policymakers spend an inordinate amount of their time trying to ensure that Japan looks good internationally even at the expense of achieving concrete policy results.

One of the “practical” applications of prestige diplomacy is that it accords with Tokyo’s desire to attain a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Washington policymakers seem to have largely succeeded in convincing the Japanese elite that they will never be accepted as a serious candidate for a permanent seat unless they meet their “responsibility” to send Japanese troops on international peacekeeping missions that include combat activities. Whether or not Japanese military missions would actually bring them any closer to a permanent seat on the UN Security Council is another matter, but important in this context is the belief of many Japanese policymakers that it is a necessary step on that road.

Japanese see themselves as the most advanced power in Asia. For some Japanese conservatives, an anti-piracy mission along the Somali coast would be an important reaffirmation that they still belong to the elite club of world leaders.

3. Utilizing the Japanese Navy

When the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, the MSDF quietly emerged as the world’s second most-powerful navy. This was a sort of embarrassment of riches in light of the fact that the Japanese Constitution forbids “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential.” This dilemma was inherent in the very creation of the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) in 1954, but by 1991 the notion that Japan did not possess “war potential” had become laughable. Indeed, it was in reality one of the most advanced and powerful military powers in the world, though it was still hesitant to use that power in light of the continued skepticism of the use of force by the Japanese public.

Two major reasons account for the dramatic growth of Japanese naval power in particular. One was consistent pressure from Washington for the MSDF to play a larger role in containing Soviet sea power in East Asia. The other was a product of Japan’s dramatic economic growth after 1960: Although military spending was generally kept below one percent of the national budget, that still represented far more money for military equipment than most other countries had available for such purposes.

One implication was that as the actual capabilities of the MSDF expanded, so too did internal and external expectations that Tokyo would be willing to employ its impressive capabilities. In 1981, Japan agreed to take responsibility for defending its own sea lanes out to a thousand mile radius from the home islands. This gave the MSDF theoretical responsibilities ranging as far as Taiwan and perhaps the Philippines. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 left the MSDF with the only major naval force in East Asia other than the US Navy.

So what did the MSDF do at this time? They continued their ship-building program, and began to shift increasingly toward the creation of an offensive—rather than strictly defensive—military capability. This offensive capability was best symbolized by the 2007 launching of the JDS Hyuga, a helicopter aircraft carrier that is officially described as a “helicopter-carrying destroyer” in order to alleviate legal questions and political sensitivities.

Not surprisingly, there seem to be many MSDF officers who do not want to train endlessly for contingencies that would never be authorized to act upon, or to let their high-tech vessels sit idle in port gathering rust. Also, there are civilian politicians who have concerns akin to the one once famously expressed by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright when speaking to Joint Chief of Staff Colin Powell: “What’s the point of you saving this superb military for, Colin, if we can’t use it?” [11]

One of the key factors driving Tokyo toward deployment of the MSDF against Somali pirates is the need for the Japanese navy to justify the substantial budget that it has been given by the government, as well as to provide practical experience for Japan’s military forces.

4. Keeping Up the with Chinese

Practical experience for Japanese military forces appears to be an urgent matter for many Japanese conservatives because they fear—and some even expect—that Japan will have to resist Chinese military pressure in the future.

Indeed, much of what has been said above about the MSDF seems to apply with equal force to the Chinese Navy. The Chinese too have been gradually increasing the capabilities of their sea forces. This includes the purchase of more sophisticated destroyers from Russia and the recent announcement that Beijing is considering the possibility of building its own first aircraft carrier. [12] Of course, it could be that the Chinese military is only responding to the strength of Japan’s navy and the launching of the JDS Hyuga.

In late December 2008, Beijing announced that it would participate in anti-piracy operations near Somalia. The motives for this decision seem to be a combination of the desire to give more operational experience to the Chinese Navy and to demonstrate China’s newfound status as a “responsible stakeholder” in the international community.

Chinese Aegis Destroyer

Chinese Aegis Destroyer

Beijing’s announcement lit a fire under Japanese conservatives like few other developments could have. Several Japanese fears had unexpectedly coalesced. Beijing was doing in practice what Tokyo had been pining to do for some time. Moreover, the implication was that the Chinese Navy would soon be working side-by-side as partners with the US Navy while MSDF officers sat sullenly in their quiet offices. In this context, Waseda University Professor Shigemura Toshimitsu told The Telegraph: “The government, diplomats, and the policymakers in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are very afraid. Before, China did not feel able to cooperate in global military operations with the US or other nations, but that has clearly changed. I foresee Beijing increasingly projecting its power overseas in the future.” [13]

In short, Beijing’s decision to participate in anti-piracy operations along the Somali coast instantly elevated the issue to an urgent priority for conservative Japanese policymakers. What may have seemed to them previously as a way to burnish their international credentials was now, in their estimation, a serious issue of long-term national security.

5. Connecting with Yemen

One little-noticed side effect of the anti-piracy campaign is that it is likely to strengthen Japanese relations with Yemen. In fact, Japanese and Yemeni diplomats have clearly recognized this possibility since at least September 2008. At that time, Japanese Ambassador in Sanaa Toshikage Masakazu told Yemeni Minister of Transport Khalid Ibrahim al-Wazeer that Japan was considering the provision of additional support to Yemen in order to train its coast guard and to establish a regional center for combating maritime piracy. [14]

Yemen followed up by hosting a regional meeting on combating piracy in late October 2008 and deploying about one thousand soldiers and sixteen military boats to ward off piracy in its regional waters. The Yemeni Transportation Ministry announced that they would set up three centers for monitoring the international waters in the Gulf of Aden. [15]

In late December, Tokyo declared that Japan would provide patrol boats and other vessels to Yemen for use in anti-piracy operations. These patrol vessels are equipped with bulletproof glass and other devices that qualify them as “weapons” under Japanese law and therefore infringe on Japan’s ban on arms exports. However, Tokyo planned to waive the usual legal restrictions in this case. [16] In fact, many of the same measures had been taken by Tokyo a few years earlier with respect to piracy near the Straits of Malacca.

The combined effect of these new anti-piracy measures is to tighten Japan-Yemen relations in a way that had not been the case in the past. Not long ago, the main bilateral link between Japan and Yemen was Overseas Development Assistance. These anti-piracy efforts add an important new layer to this connection, and it comes, perhaps not coincidentally, at a time when Yemen is initiating a modest oil and gas development program with involvement by Japanese companies.

It is not yet clear if a MSDF mission would play a substantial role in furthering the build-up of this particular bilateral connection, but it is apparent that Sanaa is seizing the opportunity provided by Somali piracy to enhance their own international role. The measures that Tokyo is now taking in regard to Yemen might just as easily have been an alternative to direct MSDF military action rather than a supplement to it.

6. Dividing the Political Opposition

One final fringe benefit for the LDP that would come out of an MSDF deployment to the Somali coast is that it puts pressure on the motley coalition of forces nipping at the heels of the ruling party. The plain fact is that the LDP’s many opponents do not share a unified ideological perspective, and security policy is one of the main fissures running through the opposition forces.

Even before the government began serious consideration of sending the MSDF to East Africa, some of the more hawkish elements of the DPJ began utilizing the issue as a way to distinguish their party’s policies from LDP policies. The various wings of the DPJ had united in opposition to SDF deployments in both Iraq and in the Indian Ocean, but that did not mean that the hawkish wing was opposed to military deployments in principle; they wanted only to argue for different deployments than those embraced by the government.

In mid-October 2008, DPJ lawmaker Nagashima Akihisa invited Prime Minister Aso Taro to comment on a proposal that the Japanese government might send MSDF escort ships to the Somali coast. He asserted, “Escorts by SDF ships would be very effective. The dispatch would not be for the purpose of the use of arms.” [17] DPJ lawmaker Asao Keiichiro added: “A crackdown on pirates would be more effective to promote Japan’s contribution to the international community than the [Indian Ocean] refueling mission.” The Prime Minister responded: “That kind of proposal is very good. Let us study it.” [18]

Of course, when the government actually began to advocate an MSDF Somalia mission itself, the DPJ backed off its previous support for the notion and started raising various objections. On one level, this reflected DPJ leader Ozawa Ichiro’s cynical political tactics. At another level, it reflected the fact that lawmakers such as Nagashima Akihisa and Asao Keiichiro were leading DPJ hawks, and that most of the remainder of the party was never that enthusiastic about their proactive military proposals.

The foreign policy divisions within the Japanese political opposition more generally, and the DPJ specifically, have existed for many years, and the anti-piracy issue is unlikely to create any serious splits before the next Japanese general elections. Nevertheless, for LDP lawmakers there must be a sense of pleasure in being able to force the opposition to confront its internal controversies about politically sensitive issues of security policy.

Japan in the Deep Waters of National Interest

As can be perceived from the preceding discussion, there are a number of plausible reasons for, as well as practical benefits to, Tokyo’s desire to send the MSDF to the Somali coast: Tokyo would gain enhanced political prestige; the military alliance with the United States would be strengthened; the capabilities of Japan’s navy would be put to use; Beijing would be put on notice that Japanese won’t be pushed around; and the opposition parties would face political strain. Given this host of benefits for the ruling party, the MSDF will probably be sent to East Africa within a few months.

These benefits, however, should not obscure some of the broader ethical and political issues. In the first place, the military suppression of Somali pirates, should it come to pass, will not do anything to resolve the fundamental problems of that region unless they are accompanied by political and economic efforts that so far have been lacking. As can be perceived, the emergence of large-scale piracy in Somalia is itself a symptom of a deeper political problem; namely, that Somalis have been abandoned by the major powers, and when they have come close to solving their own most pressing problem by themselves—the establishment of a more stable political order—they have been prevented from doing so by interventions from powers posing as the guardians of international political stability.

In this context, the rush to deploy warships against Somalia by Japan and other leading powers does not seem to be motivated by anything resembling the best interests of the Somali people, but simply by annoyance that a disenfranchised group with guns have gotten in their way and have cost them some money. Certainly, piracy is a violation of international law, puts human lives at risk, and has the potential to cause serious environmental damage if a tanker dumps its oil cargo into the sea. The Somali pirates must inevitably be put out of business. However, the self-serving posture of Japan and other nations suggests that this conflict is in a very real sense the warfare of the world’s rich against the poor. After all, why have the arguments about Somali piracy been so conspicuously bereft of any debates about the general welfare of Somalia?

With this point in mind, it becomes clearer that the motives and benefits listed above amount to little more than a power game. Put another way, it is about a narrow conception of national interests that in the long run will likely be detrimental, not supportive, of international peace and security. The pirates may be suppressed by lethal force employed by a multilateral coalition, but the underlying inequities of the international order will only be exacerbated. The predictable long-term result of this action and others like it will be a loss of confidence in potentially stabilizing international organizations, increased mutual distrust, and ultimately the rise of shriller forms of nationalism among many of the great powers. The global experience of the late 19th century ought to serve as fair warning as to where this all leads.

Indeed, in Japan there is a potent seventh motive that hasn’t yet been mentioned. The anti-piracy mission is an ideal opportunity to further the hollowing out of Article Nine of the Japanese Constitution and the spirit behind it which counsels “trusting in the justice and faith of the peace-loving peoples of the world.” If the MSDF starts shooting and killing Somali pirates, then the most serious restriction imposed by Article Nine will be rendered moot.

Of course, only a fool would trust fully in other nations’ justice and peace-loving nature. But on the other hand, to abandon completely the notion that other peoples can even understand justice and peace, or that they can act from those motives, simply opens the door to a Hobbesian nightmare in which everyone becomes the loser. Fear of disappointment or of being called naïve ought not prevent awareness that the creation of some degree of mutual trust is a sine qua non of creating a stable international order. Violent suppression alone won’t do it. There needs to be a positive goal that accompanies each military objective. In the case of Somalia, we’ve yet to see any such thing.

The Japanese Constitution was once envisioned as being a key step along the road to a better and more stable international order, but in recent years Japanese leaders seem determined to embrace a lowest-common denominator form of normality. Ultimately, this will prove to be a betrayal of Japan’s genuine national interests, and may lead to the threshold of an entirely different Gate of Tears.

Notes

[1] Asahi Shinbun, “Ships Detouring to Avoid Pirates,” December 2, 2008.

[2] Afrol News, “Eritrea Blames US for Somali Piracy,” November 21, 2008.

[3] Connie Levett, “Fishing Fleets are Pirates, Too,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 24, 2008.

[4] Alastair Dalton, “Ocean of Opportunity for Modern Pirates,” Scotsman.com News, November 19, 2008.

[5] GDP per capita income figures from the CIA World Factbook.

[6] Yomiuri Shinbun, “Govt to Bring Antipiracy Bill Before Diet,” January 7, 2009.

[7] Yomiuri Shinbun, “MSDF May Be in Somali Waters by March,” January 16, 2009.

[8] AFP, “US Envoy Urges Japan to Join Somalia Anti-Piracy Mission,” January 9. 2009.

[9] Yukio Okamoto, “Japan and the United States: The Essential Alliance,” The Washington Quarterly, Spring 2002, p. 64.

[10] Kenneth B. Pyle, Japan Rising: The Resurgence of Japanese Power and Purpose, PublicAffairs, 2007.

[11] Madeleine Albright, Madam Secretary: A Memoir, Miramax, 2003, p. 182.

[12] Edward Wong, “China Signals More Interest in Building Aircraft Carrier,” New York Times, December 23, 2008.

[13] Julian Ryall, “Japan Concerned Over US Relations with China,” The Telegraph, December 23, 2008.

[14] Saba News Agency, “Yemen Seeks Japanese Support for Establishing Regional Fighting Piracy Center,” September 7, 2008.

[15] Saba News Agency, “Yemen to Host Regional Meeting on Combating Piracy,” September 16, 2008.

[16] Kyodo News, “Yemen to Get Patrol Boats to Fight Piracy,” December 24, 2008.

[17] Michael Penn, “DPJ Hawks Call for a Military Anti-Piracy Role in Somalia,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 1170, October 19, 2008.

[18] Ibid.

Michael Penn is Executive Director of the Shingetsu Institute for the Study of Japanese-Islamic Relations and a Japan Focus associate. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal. Posted at Japan Focus on January 20, 2009.

Recommended citation: Michael Penn, “Somali Pirates and Political Winds Drive Japan to the Gate of Tears,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 4-2-09, January 20, 2009.

Michael Penn’s articles at The Asia-Pacific Journal include:

Is There a Japan-Iraq Strategic Partnership?

Oil and Power: The Rise and Fall of the Japan-Iran Partnership in Azadegan

Michael Penn contributed the following updated to as Shingetsu Newsletter No. 1265 on January 29, 2009.

MSDF SOMALIA ANTI-PIRACY MISSION TO BE LAUNCHED SOON

Yesterday the Japanese government announced that it had decided to deploy the MSDF on an anti-piracy mission to the Somali coast on the basis of the current SDF law. Yasukazu Hamada, the minister of defense, said he had ordered the force to prepare for deployment, which may take place as early as March. He did not offer details about the possible size of the naval mission. Hamada said, “The pirates in the Gulf of Aden off the coast of Somalia pose threats to Japan and the international community and are an issue that should be dealt with swiftly.”

The International Maritime Bureau has reported that 111 ships were attacked in 2008 off the eastern coast of Somalia and in the gulf. Forty-two of these vessels were hijacked, and a dozen are still being held, including the Japanese-owned Chemstar Venus.

The Defense Ministry is not entirely happy with this mission. Since the legal basis of the mission is shaky, the rules of engagement are likely to be somewhat impractical. Article 82 of the SDF law, on which the MSDF anti-piracy dispatch will be based (at least initially), stipulates that ships the MSDF can protect are limited to:

— Japan-registered ships.

— Foreign-registered ships operated and controlled by Japanese shipping companies.

— Foreign-registered ships carrying cargo being transported to Japan.

Sounds good, but how are MSDF vessels really going to know the exact identity of each and every ship passing through the Bab al-Mandab? How are they going to know whether or not a ship carries “cargo being transported to Japan!”? How much cargo is cargo? One cigarette? The MSDF is not allowed to protect ships that are not Japanese or Japan-related. If such ships are attacked by pirates within the range of the MSDF, the MSDF plans to just call some other nations’ navy for help.

The Defense Ministry is well aware of these legal problems, and this is precisely why they have been asking the government to give them clear guidelines. “There’s a limit on what we can do under the current laws,” said a senior MSDF officer to the Yomiuri Shinbun, “I want the government to properly explain to the public what the MSDF can and can’t do.” Defense Minister Hamada has repeatedly called for a new law: “This is only a stopgap measure… I believe the MSDF should engage in anti-piracy activities under a new law.”

The SDF has many friends in the Diet and elsewhere who are eager to draw up just such a law. Among them is Masahisa Sato, the soldier-politician we introduced in Shingetsu Newsletter No. 1104 (August 2008). Sato backs both a new law as well as the current mission: “The participating countries [are] occupied by actions to protect their own countries’ or related vessels. For now, Japan will not be criticized even if the MSDF flotilla escort only Japanese and Japan-related ships.” Another voice in support of the mission has come from former Defense Agency Vice-Minister Masahiro Akiyama, who asserted, “Japan has the second largest naval power in the Asia-Pacific region after the United States. It’s not an option for Japan to decline to dispatch the navy.”

However, the key political backer all along has been Prime Minister Taro Aso himself. As the Yomiuri notes: “A big factor behind the turning of the tide in favor of the dispatch was Aso succeeding Fukuda as prime minister in September. Hamada had persistently expressed reluctance about the plan, but Aso reportedly won over Hamada by asserting that Japan should do as much as it could.”

Also strongly lobbying for the anti-piracy mission is the Japanese Shipowners’ Association, who are losing significant sums of money due to the pirate activities. The president of this organization, Hiroyuki Maekawa, has been deeply involved with talks with the Defense Ministry about how the MSDF mission will work in practice. According to the Yomiuri Shinbun (which is following this story much more closely than the other papers) the outlined plan features a convoy system in which Japanese commercial ships will be accompanied by two MSDF vessels — one in front and one behind. One convoy escort mission will take about three days. The MSDF fleet will continue activities while procuring supplies at nearby ports. Theoretically, the Defense Ministry will receive a notice issued by the Japanese Shipowners’ Association and conveyed by the Construction and Transport Ministry about each ship to be escorted by the MSDF prior to its departure for pirate-infested waters. A senior MSDF official commented, “We aren’t going to get rid of all the pirates, but we’ll deter pirate attacks and ensure the security of Japan-related ships.”

It should also be noted that the Defense Ministry’s plan calls for destroyer-borne helicopters to play a significant role in surveillance activities for the convoys. The helicopters will be equipped with 7.62-millimeter machine guns, and members of the MSDF’s Special Boarding Unit will be aboard. When an MSDF destroyer spots a suspected pirate ship, it will warn the pirate ship via radio not to approach the convoy. If the ship doesn’t respond, the MSDF will be authorized to fire warning shots. What happens after that? Well, it sounds like it’s in the Hands of God.

Some senior MSDF officers seem to be seeing this mission as a long-awaited chance for redemption of the military honor: “During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy could not protect the nation’s transport convoys. We have to regain the trust of the shipping industry, which was lost during the war.” According to the Yomiuri, such an outcome would “clean this historical taint.”

Let me get this straight: Japan’s “historical taint” from World War II is all about the fact that the military wasn’t strong enough to carry out its missions? This is the central issue?

World! You have been warned!

![Somali Pirates and Political Winds Drive Japan to the Gate of Tears [Updated]](https://apjjf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/goldennori.jpg)