Foundations of Cooperation: Imagining the Future of Sino-Japanese Relations

Matthew Penney

Introduction

In the last week of 2007, Japanese Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo made an official visit to

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao shakes hands with the visiting

Japanese Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo in Beijing, December 28, 2007.

When Koizumi stepped down in September 2006, his successor, Abe Shinzo, quickly chose to visit

Analysts of East Asian politics, however, still warn of continuing tensions. Popular works – from Japanese manga diatribes to hate speech on Chinese internet messages boards – have been singled out by many commentators as indicative of hostility in the public space of both countries.[3] In the Japanese case, works that pump up

In a previous article, I noted that in 2005 and early 2006, arguably the low point in China-Japan relations since the restoration of diplomatic ties in 1972, a variety of works of Japanese popular non-fiction represented China in a reasonable way and served as an important counterpoint to crude “China-bashing” titles that monopolized international attention.[4] Japan Focus has paid close attention to neo-nationalist perspectives, offering important analysis of their rhetorical strategies and frequent excesses.[5] More attention needs to be given, however, to the even more prolific and influential body of writing with a conciliatory focus. Many works released since the 2005 protest movement, including titles published in

This article extends the examination of the representation of

The works discussed in this paper are not from small left-wing publishers like Akashi Shoten – producer of an array of progressive titles. They emanate rather from the non-fiction paperback series of

Recent representations of

Positive Images

Neo-nationalist publications like Manga Chugoku nyumon and some more recent works present

An important counter-measure to neo-nationalist diatribes is to “normalize”

Authors of important works of Japanese popular non-fiction have responded successfully to these challenges in two important ways. First, some of the best of these criticize both

Nitchu kankei no kako to shorai (The Past and Future of Sino-Japanese Relations) by Okabe Tatsumi, an academic and China specialist, appeared in the popular bunko format in December of 2006.[8] Iwanami Shoten, the book’s publisher, is a progressive press that seeks to present academic perspectives in popular form. The book’s subtitle “transcending misunderstanding” points toward a hopeful common future.

Nitchu kankei stresses the mutual influence and interrelationships that characterize Sino-Japanese relations. Peace and friendship are advanced as natural and appropriate goals for both powers to be achieved through mutual understanding. Okabe presses for a problem-solving approach to Sino-Japanese relations. “Can we really say that ‘

The orientation of the majority of Japanese academics in the humanities and social sciences, and of presses that publish a range of relevant titles like Iwanami and Akashi Shoten, is positive about the future of China-Japan relations. What is particularly striking is that the hopeful vision presented in Nitchu kankei is shared by popular works in all of the major paperback non-fiction series. The majority clearly anticipate closer relations between

Shimizu Yoshikazu’s Jinmin Chugoku no shuen (The End of the People’s Republic of

In contrast with neo-nationalist writings that mock

Jinmin Chugoku offers a dual approach to

Jinmin Chugoku presents some of

Tanaka Naoki’s Hannichi o koeru Ajia (Asia Transcends “Anti-Japaneseness”) was published by Toyo Keizai Shinposha in November of 2006.[12] The book’s title uses the term “hannichi” (anti-Japanese) – a media buzz-word in Japan in the aftermath of the 2005 Chinese protest movement – as a starting point for imagining improved relations in East Asia. Much of the book is devoted to examining

The imagined end result of this reflection is an “East Asian Economic Community” envisioned as a common goal: “As we enter the 21st century, the idea of an ‘East Asian Economic Community’ has been raised repeatedly both within

The Nikkei newspaper –

Chugoku daikoku starts with a common comment from businessmen returning from

Chugoku daikoku highlights the centrality of

While accenting the positive, these works do not spare criticism of

When presenting criticism, Chugoku o shiru takes a similar approach to the earlier Nikkei title. It first draws attention to rural poverty by using Chinese critiques and assessments of the problem. It then goes on to make more subtle comparisons – the author uses the terms kachigumi (the winning team) and makegumi (the losing team) – central to contemporary Japanese social and economic discourse – to describe the Chinese who have surged forward and those who have been left behind in their consumer / capitalist revolution.[20] Adopting the same terms used in Japanese discussions of inequality stresses familiarity and shared dilemmas. Frequent comparisons between

Chugoku wo shiru does offer criticisms, but typically by the direct comparison of shared negatives in

In Nikkei writing,

Nikkei titles deal with all aspects of contemporary Sino-Japanese circumstances and relations. Works in other series often focus on a single issue, but are similarly optimistic. Taoka Shunji’s Kita Chosen, Chugoku wa dore dake kowai ka (Just How Scary Are North Korea and China?) was released as a part of Asahi’s shinsho series in March 2007.[22] Taoka, a leading writer on military affairs, warns: “Don’t make China out to be an enemy,”[23] arguing that China will become a threat only if Japan imagines that it is so and refuses to constructively engage its continental neighbor.

Taoka plays on the fact that the Japanese word for “hawk” (taka) rhymes with the word for “idiot” (baka) and describes what he sees as “the idiots who can’t break away from Cold War thought”.[24] To encourage readers to abandon Cold War tropes, he offers a complex series of comparisons designed to deconstruct the “China threat”. Taoka describes increases in Chinese military spending as “a phenomenon very much like that seen during

Taoka is selectively critical of the Chinese side, raising issues such as the reclassification of soldiers as “public security officers” to obscure Chinese military spending levels. He calls for more transparency while noting that that many nations, including

Amako Satoshi, an academic who has written widely about Chinese history, wrote Chugoku, Ajia, Nihon (

Amako believes that

To promote deeper Sino-Japanese cooperation, this literature highlights

Amako also sees major changes in Chinese society as likely. He views international exchange as having the potential to change

Amako is not only calling for change in

In the end, Amako presents the creation of an “East Asian Economic Community” devoted to partnership and free of hegemonic drives as the best way forward, concluding that “improvement of relations with

Journalist Kondo Daisuke’s Nihon yo, Chugoku to domei seyo! (

Kondo wants partnership between

Works that focus on

Atarashii Chugoku, Furui daikoku (New China, Old Superpower) by Sato Ichiro, a leading academic commentator on Chinese culture, was published by Bungei Shunju in March 2007.[39] In some circles, Bungei Shunju has a rightwing reputation, so it is important to note that this title explores Chinese literature and traditional culture as the foundation for a positive contemporary order linking Japan and China.[40]

Atarashii Chugoku is filled with comments like “The influence of Chinese literature on

While welcoming

Few titles among the new shinsho and bunko treatments of

Higurashi sees his work as a “warning” to Japanese people about the territorial ambitions of their neighbors. He does not favor an aggressive military stance, however, advising instead that

In the latter part of 2006 and early 2007, the tone of Japanese popular non-fiction works in major series mirrored the “thaw” in Sino-Japanese relations. Authors achieved this by turning to a number of notable non-fiction techniques: using the authorial voice to explain why generalizations and stereotyping are harmful, presenting Japanese and Chinese negatives in parallel, evoking memory of Japan’s high growth period through comparisons with China now, stressing the familiar rather than the different, engaging with Chinese voices in a pattern of representation that includes extensive quotation, and predicting the future – an imaginative exercise – in a way that makes closer relations and cooperation seem desirable, essential, and increasingly likely. Popular non-fiction titles like the ones discussed in this essay are both inexpensive (the average cost of the titles discussed would be around $6.00 US) and ubiquitous. Conciliatory approaches, however, are not limited to nonfiction books. Similar

Manga

Manga has been widely discussed in English-language commentary because of its prominence in the Japanese consumer environment and position as one of

Manga Chugoku nyumon has been widely noted for its extremist denigration of Chinese culture. While critics have frequently analyzed Manga Chugoku as the manga representation of

Chugoku no hone wa ippon sukunai (China Has One Less Bone) was written and illustrated by Oda Sora, an Okinawan artist who now divides her time between China and Japan.[44] The title is a follow-up to the author’s pair of popular Chugoku ikaga desu ka (How About Some China?) books published in 2000 and 2003.[45] Oda’s China representation is as different from the essentializing Manga Chugoku nyumon as is imaginable. Stylistically, her work is very similar to Oguri Saori’s Darling wa gaikokujin (Darling Is a Foreigner) books that drew attention in Japan and internationally with their heartwarming portrait of the creator’s international marriage.[46] In the case of Chugoku no hone, however, Oda is sketching her connections with China and its culture. Here, too, the relationship is drawn with humor, optimism, and an acceptance of difference.

Chugoku no hone author Oda discovers some of her childhood favorites – “Little Red Riding Hood”, “The Ugly Duckling”, and “Cinderella” – in a Chinese bookshop.

The title Chugoku no hone refers not to the individual or national body, but to the Chinese written character for “bone” which can be drawn with one less stroke of the pen than the Japanese version. She writes – “Bone and bone. However, it’s not as if we can say that either

Oda uses acknowledgement of the validity of Chinese perspectives to criticize

Chugoku no hone humanizes ordinary Chinese and gives Japanese readers a view of a country that in important ways resembles their own. The manga’s detailed description of the largest bookstore in

Chugoku no hone is an overwhelmingly positive work. This does not mean, however, that no criticisms of

Chugoku to no tsuki ai kata ga manga de sanjikan de wakaru hon (A Guide to Understanding Relations with

Like other progressive titles, Chugoku to no tsuki ai kata struggles to critically discuss

The folktale character “Monkey” guides Japanese readers toward closer Sino-Japanese relations.

Narrative manga are the most important part of the manga market and several popular titles put forward positive images of

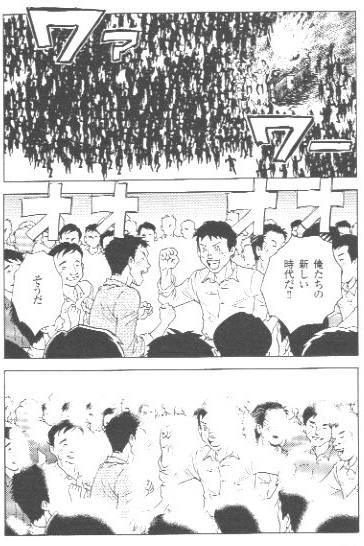

Dawn begins with a scathing attack of Japanese society as seen from the point of view of Tokyo’s homeless.[54] The main character of the series, Yahagi Tatsuhiko, is a former Wall Street fund manager who has dropped out and joined the ranks of the homeless in order to see society from a new perspective. He emerges with the recognition that many of the homeless that he meets were committed salarymen cut loose during

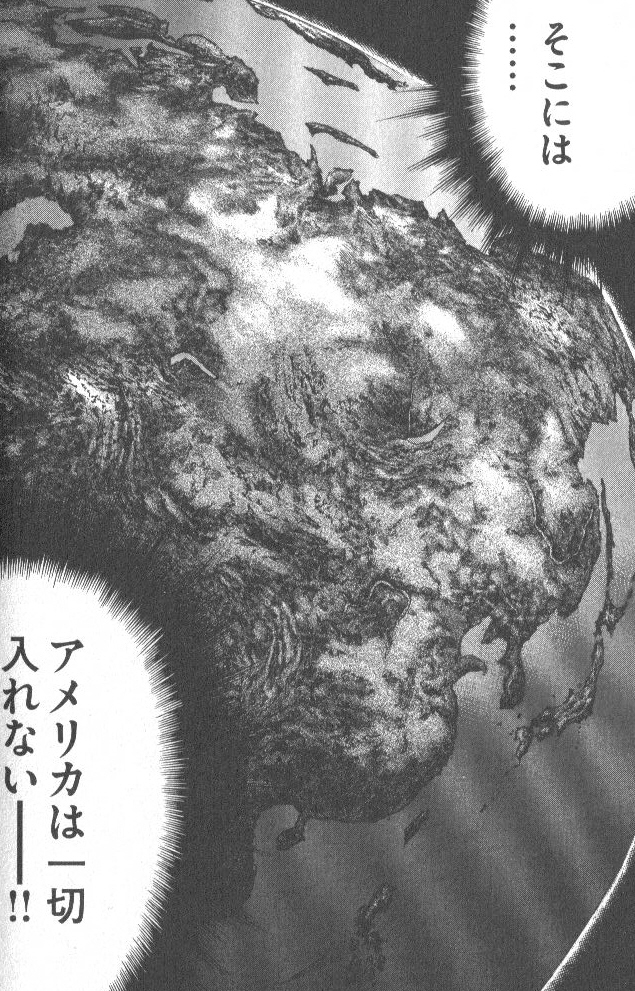

There are elements of farce in the first parts of Dawn as Yahagi takes the homeless to an expensive eatery. When they are denied service, he buys the restaurant. The discussion quickly turns serious, however. Yahagi decides to make use of the talents of his homeless friends and form a new company, the “Asian Farm Corporation”, to organize transnational cooperation in agriculture. He wants to counter what the manga represents as American bullying over trade in agricultural products. Yahagi seeks to team up with Chinese companies and businessmen to invest in

From Dawn. “America won’t be able to set one foot in here.”

In Dawn, the central characters strive to create an “Asian Economic Community” that can reorient the conditions of globalization to benefit developing countries.

In imagining the future of Sino-Japanese relations, Dawn does not ignore the past. The blame for the poor state of political relations that prevailed in the 2000s is placed squarely on

Ex-Prime Minster Koizumi relegated to the role of “bad guy” in Dawn.

Elsewhere, the behavior of the Japanese government is contrasted with that of

“

Far from being ignored in Japanese popular culture, this type of perspective is actually being played up in mainstream manga.

Dawn also grapples with one of the central problems in

Dawn holds “

The Chugoku no rekishi (History of China) manga series published by Shueisha was edited by

Chugoku no rekishi deals very critically with

The book tries to capture the enthusiasm for change evident after the founding of the People’s Republic. Mao is presented as a benevolent figure who agonizes over the suffering of the people and, as a character in the work, speaks mostly in quotations from his most idealistic writings. The darker side of Mao never comes out. For example, starvation during the “Great Leap Forward” is attributed to “natural disasters and other factors”, obscuring Mao’s and the Chinese government’s responsibility for the famine.[58] It is notable that this approach characterizes the major work on Chinese history for Japanese children. The attempt to forge a largely positive story out of

An idealistic depiction of Mao declaring the founding of the People’s Republic of China in Chugoku no rekishi.

The Tiananmen Square Massacre is the only instance of human rights violation given prominence in Chugoku no rekishi. The coverage of the massacre is extensive and the authors report that “many were killed”.[59] Still, this section is a blip in the narrative, not connected with any extended discussion of human rights. The story returns directly to Deng’s economic plans bringing prosperity to

A child, Yanyan, becomes the focus. His family are bicycle manufacturers and live in a new middle class apartment building with an air conditioner. The boy studies traditional Chinese culture and calligraphy. Chinese people are thus shown as being in touch with their traditions and past while become prosperous. The boy’s grandfather reflects that “Over our long history, the Chinese people have passed on their lives from parent to child and worked hard to achieve happier lives. Today’s

Yanyan and his family have prospered and look forward to a happy future.

Problems and Prospects

This essay has examined a range of Japanese images of

We have noted that most neo-nationalist works are niche publications. It is “positive” images that have proliferated in the major non-fiction series published in

The categories “progressive” and “neo-nationalist” have become even more blurred. In the past, far right manga like Kobayashi Yoshinori’s polemics relied on a unique, editorializing style that set them apart from other manga titles.[64] With its extensive text, this form of manga clearly aimed at adult audiences. The recently published work of Nanking denial, Manga de yomu Showa-shi, Nankin daigyakusatsu no shinjitsu (Reading Showa History Through Manga – The Truth of the Nanking Massacre), however, is stylistically identical to progressive history manga like Chugoku no rekishi.[65] While it is not being placed in the children’s section of major booksellers, Japanese consumers will have an increasingly difficult time identifying just which works are mainstream and which extremist. If these boundaries blur in high profile cases, an angry popular backlash in

On January 30, 2008, several Japanese were sickened after eating dumplings manufactured in

The existence of a rightwing niche that can be successfully tapped for profit could block the path toward better Sino-Japanese relations, especially as it is sometimes hard to distinguish between progressive, mainstream, and neo-nationalist works. Problems are not exclusively on the neo-nationalist side, however. “Positive” representations of

“Positive” representations of

There are other weaknesses in the attempts to grasp the nature of Chinese growth. Many images of

The most serious potential problem, however, is that the presentation of Japan in many of these works, including titles that present China in a positive way, as a model member of the international community and future co-leader of an “East Asian Community”, is closely linked with Japanese nationalism.[68] Imagining Japan as guiding China or as being an ideal that China should strive toward remains attractive to many Japanese.

The imaginative projects discussed in this article are self-serving of Japanese interests but not xenophobic, and while some of the images are distinctive, they are hardly limited to

Nationalism frequently makes its way into academic discussions as a negative. This is understandable, given the role that nationalism has played in sparking international conflict, inequality, and discrimination. A January 2007 survey carried out by

There are certain remarkable similarities in Japanese and Chinese representations of the relationship between the two countries. During the period of “thaw”, the Chinese leadership has frequently referred to

Some Chinese official statements are even more optimistic than Wen’s. The importance of cooperation with

Nationalist yet “positive” imaginings of

Matthew Penney is Assistant Professor at Concordia University. He is currently conducting research on popular representations of war in

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on April 5, 2008.

NOTES

[1] Xinhua News Agency, “Fukuda: China’s economic growth an opportunity to Japan, world”, December 26, 2007.

[2] Robert Porter, Ideology: Contemporary Social, Political and Cultural Theory,

[3] See, for example Norimitsu Onishi, “Ugly Images of Asian Rivals Become Bestsellers in

[4] Matthew Penney, “

[5] See, for example, Rumi Sakamoto and Matt Allen, ““Hating ‘The Korea Wave’” Comic Books: A sign of New Nationalism in Japan?”, Japan Focus.

[6] Mel Gurtov, “Reconciling Japan and China”, Japan Focus.

[7] B-Net Business Network, “Chinese feelings toward Japan show signs of evolving” B-Net Asia Political News. In addition, many have noted that Chinese official references to Japanese war crimes have been toned down in recent months. See, Associated Press, “China remembers ‘Nanking Massacre’”, USA Today, December 12, 2007.

[8] Okabe Tatsumi, Nitchu kankei no kako to shorai,

[9] Ibid., p. 4.

[10] Shimizu Yoshikazu, Jinmin Chugoku no shuen,

[11] Shimizu Yoshikazu, Chugoku ga hannichi o suteru hi,

[12] Tanaka Naoki, Hannichi o koeru Ajia,

[13] Ibid., p. 21.

[14] Ibid., p. 31.

[15] Ibid., p. 40.

[16] Ibid., p. 9.

[17] Nikkei Keizai Shimbunsha, Chugoku daikoku no kyojitsu,

[18] Nihon Keizai Shimbunsha, Chugoku daikoku no kyojitsu, p. 3.

[19] Yukawa, Chugoku o shiru, pp. 15-18.

[20] Ibid., p. 26.

[21] Ibid., pp. 134-135.

[22] Taoka Shunji, Kita Chosen, Chugoku wa dore dake kowai ka,

[23] Ibid., p. 268.

[24] Ibid., p. 19.

[25] Ibid., pp. 138-139.

[26] Amako Satoshi, Chugoku, Ajia, Nihon,

[27] Ibid., p. 10.

[28] Ibid., p. 12.

[29] Ibid., p. 12.

[30] Ibid., p. 32.

[31] Ibid., pp. 40-41.

[32] Ibid., pp. 21-22.

[33] Ibid., p. 203.

[34] Kondo Daisuke, Nihon yo, Chugoku to domei seyo,

[35] Ibid., p. 11

[36] Ibid., p. 19.

[37] Marukawa Tomoo, Gendai Chugoku no sangyo,

[38] Ibid., p. 237.

[39] Sato Ichiro, Atarashii Chugoku, Furui daikoku,

[40] Iris Chang frequently described Bungei Shunju as “ultra right-wing”, see [http://www.irischang.net/press_article.ctm?n=9]

[41] Sato, Atarashii Chugoku, p. 75.

[42] Ibid., p. 195.

[43] Higurashi Takanori, Okinawa o nerau Chugoku no yashin,

[44] Oda Sora, Chugoku no hone wa ippon sukunai,

[45] Oda Sora, Chugoku ikaga desu ka,

[46] Oguri Saori, Darling wa gaikokujin,

[47] Oda, Chugoku no hone, p. 144.

[48] Ibid., p. 17.

[49] Ibid., p. 24.

[50] Uemura Yumi and Kakehi Takeo, Chugoku to no tsuki ai kata ga manga de sanjikan de wakaru hon,

[51] Ibid., p. 81.

[52] Ibid., p. 73.

[53] [http://www10.ocn.ne.jp/~comic/hikaku.htm]

[54] Kurashina Ryo, Dawn, Vol. 1,

[55] Kurashina Ryo, Dawn, Vol. 7,

[56] Kawakatsu Mamoru (eds.), Chugoku no rekishi, Vol. 10,

[57] Ibid., p. 13.

[58] Ibid., p. 109.

[59] Ibid., pp. 122-128.

[60] Ibid., pp. 138-139.

[61] Ibid., p. 163.

[62] Ko Bunyu, Joku de wakaru, Chugoku no wareenai genjitsu,

[63] Hayasaka Takashi, Sekai no Nihonjin joku-shu,

[64] Rumi Sakamoto, “‘Will you go to war? Or will you stop being Japanese?’ Nationalism and History in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron”, Japan Focus [http://www.japanfocus.org/products/details/2632].

[65] Hatake Natsuko, Manga de yomu Showa-shi, Nankin daigyakusatsu no shinjitsu,

[66] Takarajima, Shirazu ni taberuna! Chugoku-san,

[67] See, for example, Shin Saihin, Ima no Chugoku ga wakaru hon (Understanding Today’s

[68] For a discussion of the intersection between ideas of Japanese nationalism and Japan’s global roll, see Takekawa Shunichi, “Forging Nationalism from Pacifism and Internationalism: A Study of Asahi and Yomiuri’s New Year’s Day Editorials, 1953-2005”, Social Science Japan Journal, 10(1), 2007.

[69] Stephen Hoadley, “Pacific Island Security Management by Australia and New Zealand: Towards a New Paradigm”, Centre for Strategic Studies:

[70] David R. Morrison, Aid and Ebb Tide: A History of CIDA and Canadian Development Assistance,

[71] “Aikokushin ‘aru’ ga 78% honsha yoron Chosa”, Asahi Shimbun, 25 January 2007 [].

[72] http://english.people.com.cn/200704/06/eng20070406.html

[73] Gurtov, “Reconciling

[74] http://english.people.com.cn/200703/06/eng20070306_354780.html

Appendix – Negative Images of

This article shows that positive depictions of

Soshite Chugoku no hokai ga hajimaru (The Collapse of China Begins) was written by Izawa Motohiko, illustrated by Hatano Hideyuki, and published by Asuka Shinsha in August 2006.[1] Asuka Shinsha was the publisher of Manga Chugoku nyumon, and barely a month before Prime Minister Abe’s ice-breaking trip to China, another similar mix of racism and revisionism would have struck a sour chord in the milieu of Sino-Japanese detente. Soshite Chugoku, however, while still a negative depiction of

Overall, the vision of

A variety of other titles critical of

Despite its title stressing “danger”, Abunai! Chugoku is not without sympathetic Chinese characters. As the professor travels with a young Japanese exchange student, they encounter Chinese who wish to practice their Japanese conversation skills. Parts of the work present a friendly, thoroughly humanized portrait of the “other”. The conversation quickly lapses into criticism, however. Readers are presented with an exposition of the high rate of abortion of female fetuses in

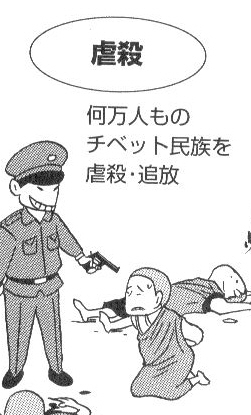

Other recent manga criticize

A demonizing image from Manga de wakaru.

Yet despite its excesses, many of the points it makes about pollution, human rights abuses, and other failings of the contemporary Chinese state are valid. The authors show concern for the oppressed, especially Tibetans and

In 2006 and 2007, major manga critical of

Watanabe Shoichi, a leading neo-nationalist commentator, since the mid-1990s has tried to ensure that Japan’s “national narrative”, as expressed in school textbooks, popular history and other genres of non-fiction, is defended against the assertions of others.[14] In March of 2007, Watanabe released Chugoku o eikyu ni damaraseru 100 mon 100 to (100 Questions and Answers to Shut China Up Forever).[15] This title is significant. Watanabe is looking to “shut up” a monolithic

Thus Watanabe not only argues that the

Watanabe is not alone in exploiting this type of approach. Ko Bunyu, the prolific anti-Chinese author of Taiwanese extraction and editor of Manga Chugoku nyumon, released Bunmei no jisatsu (The Suicide of Civilization) in May of 2007.[17] The suicide referred to in the title is pitched as “

Some of the reasons why Ko sees Chinese civilization as heading toward suicidal collapse are actually quite relevant criticisms. For example, he outlines how attempts to make Tibetans and Uighur into “Chinese” through means that individuals like the Dalai Lama have described as “cultural genocide” are bound to spark resistance that shatters national borders and national myths at the same time[19]. Support for these groups, their human rights and self-determination, however, would be better placed in a book that avoids polemical

In their negative rhetoric, the writings of Tsuge Hisayoshi, Watanabe Shoichi, and Ko Bunyu are representative of recent neo-nationalist works in

[1] Izawa Motohiko, Soshite Chugoku no hokai ga hajimaru,

[2] Ibid., p. 3.

[3] Penney, “

[4] Akebono Kikan, Abunai! Chugoku,

[5] Ibid., p. 88.

[6] Ibid., p. 97.

[7] Ajia Mondai Kenkyukai, Manga de wakaru Chugoku 100 no akugyo,

[8] Ibid., p. 58.

[9] Ibid., p. 127.

[10] Tsuge Hisayoshi, Nihonjin yo, Yahari Chugoku wa abunai,

[11] Ibid., p. 1.

[12] Ibid., p. 22.

[13] Ibid., pp. 4-5.

[14] Watanabe Shoichi, Nihonjin no tame no Showashi (A History of Showa for Japanese),

[15] Watanabe Shoichi, Chugoku o eikyu ni damaraseru 100 mon 100 to,

[16] Ibid., p. 36.

[17] Ko Bunyu, Bunmei no jisatsu,

[18] Ibid., p. 212.

[19] Neo-nationalist authors, while castigating

[20] A few of the works critical of