Mark Morris

This essay proposes looking back at a story which is one of the most unusual winners of Japan’s best-known literary award, the Akutagawa Prize. Kara Juro’s Letters from Sagawa (Sagawa-kun kara no tegami) first appeared in November 1982 in the journal Bungei; it was announced co-winner of the 88th Akutagawa Prize in January 1983, and subsequently reprinted that March in the official prize-confirmation section of the quality monthly which hosts the award, Bungei Shunju. Kara’s publisher Kawade Shobo Shinsha had already published a slim single-volume version the preceding January.

I want to go back to Letters from Sagawa for several reasons. One is that the author, Kara Juro, has had something of a come-back in recent years, not that he had ever really gone way. For example, his short story “Glass Messenger” (“Garasu no tsukai“) was adapted by him into the screenplay of the 2005 film of the same title, a film directed by the zainichi Korean director Kim Sujin, and Kara himself plays one of the lead roles in it. Kara is not well known outside Japan, so I will try to supply some basic information about this colourful, contrary person.

A second reason has to do with the cultural atmospherics of the earlier story. It seems to be closely, if eccentrically, linked to political and cultural themes of Japan in the 1980s which might be worth revisiting from the distance of several decades. This will also involve a cursory look at the literary field of the early 1980s.

A third and related matter, which the very strangeness of Letters from Sagawa might help to comprehend, has to do with a certain sense of strangeness itself. The print and online media have, not so long ago, reported on something called “The Paris Syndrome” which seems to affect young Japanese visitors to and short-term residents of Paris. Veteran BBC Paris correspondent Caroline Wyatt has recounted, via other reports in the French press and Reuters, that a ‘dozen or so Japanese tourists a year have to be repatriated from the French capital, after falling prey to what’s become known as “Paris syndrome”. . . . This is what some polite Japanese tourists suffer when they discover that Parisians can be rude or that the city does not meet their expectations’ (Wyatt 2006). I want however briefly to consider a rather more serious, historically shaped sense of estrangement and alienation experienced by Japanese and other visitors to the West from East Asia since early in the twentieth century. This is a kind of alienation, a sense of aporia (psychical, intellectual or ideological blockage) or dysphoria (psychical, existential malaise) before the lived fact of one’s otherness, often experienced most acutely on the level of language. In language, or in language thwarted, may reside a painful disaggregation of identity, which formulations about a Paris syndrome inevitably threaten to trivialize.

Kara Juro, the Japanese literary field of the 1980s, estrangement in and by language — these are complex topics that can only be sketched out all too briefly. It is their conjuncture within Kara’s Letters from Sagawa, the conditions of the story’s production and the debates surrounding this intractable text, which provide the focus of this essay.

Kara Juro

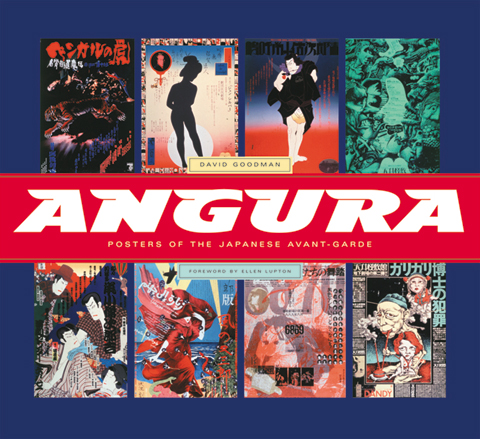

Kara is perhaps best known as one of the key figures of Japan’s “underground” – angura – theatre movement of the 1960s and 1970s. He was born in Tokyo in 1940 and graduated from Meiji University with a degree in theatre arts in 1963. That same year he helped found a drama troupe that would become one of the most colourful participants in the underground/avant-garde movement during these volatile decades: the Situation Theatre Troupe (Gekidan Jokyo Gekijo). The energy of his Situation Theatre at times spilled out onto the Tokyo streets from its signature Red Tent, leading to confrontations with Tokyo city bureaucrats, the police, and even his artistic ally and competitor Terayama Shuji (Goodman 1988: 227-82).

Consider, for example, “The Shinjuku West-Exit Park Incident” of 1969. By the beginning of that year, having been forced out of its temporary home at the Hanazono Shrine due to the criticisms of shrine officials and local business people, and having been banned by the Tokyo municipal government from performing anywhere else in the city, the Situation Theatre turned to direct action. Kara and his comrades responded by setting up their Red Tent in a small park near Shinjuku Station. As they proceeded with a performance, several hundred riot police (kidotai) – a familiar presence in the Tokyo streets of the time – surrounded the tent. Afterwards Kara, his female lead and partner Ri Reisen, and three other members of the troupe were arrested. This example of bravado, a bringing together of art and political action typical of angura theatre, earned Kara and his troupe their own niche in the popular social history of the time, since the 3 January 1969 event was immediately classified by the Japanese media as worthy of description as an “incident” (jiken): Shinjuku Nishi-Guchi Koen Jiken.[1]

As noted above, Kara has been involved in film as well as drama. His film career goes back to the end of the 1960s and roles in Oshima Nagisa’s Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (Shinjuku dorobo nikki 1968) and Matsumoto Yoshio’s Pandemonium (Shura 1971). His most recent re-engagement with cinema has come in two films directed by Kim Sujin, mentioned above, himself formerly an actor in the Situation Theatre Troupe: Wagering the Night (Yoru o kakete 1999) and Glass Messenger (Gurasu no tsukai 2005). The arts in general, and the avant-garde theatre in particular, have shown a greater openness to outsiders, to others, than many social and cultural institutions in Japan. This is especially the case with zainichi/resident Korean artists. Kara’s working life has been bound up with an alternative cultural sphere supportive of zainichi artists such as his ex-partner, and co-founder of the Situation Theatre, Ri Reisen (I Yeo-Seon), character actor Rokudaira Naomasa and actor-director Kim Sujin, one of the most significant contemporary figures in the considerable zainichi artistic community.

Kara Juro is the stage name of the man born Otsuru Yoshihide. There have been a number of famous artistic “Juro’s.” One whose career has suggestive parallels with Kara’s was Hayashida Juro (1900-67), best-known for his role in the postwar revival of Kamigata manzai (comic dialogues associated with western Japan). ‘Kara’ is written with the character otherwise read as To, as in the To – in Chinese, Tang – Dynasty. But the noun kara has meanings only loosely tied to any specific history or geography, general connotations of the foreign, exotic, the other. Kara Juro is a name which signals in the man a kind of playful extroversion that one might not expect from the bearer of the elegant Japanese moniker he was born with.[2] I will return to Kara and his cultural sphere’s zainichi connections at the end of the essay, if only to indicate the exceptional nature of Letters from Sagawa and its postmodern, rather 1980s-specific nervous playfulness about, if not downright rejection of, alterity.

One other Kara is the writer of prose fiction. This is the Kara focussed on below. During his years of acting, agitating and directing, he gained a reputation as a first-rate writer of funny, fantastic and often macabre short stories. One collection of tales won the Izumi Kyoka Prize for fantasy-genre fiction in 1978 (The Starfish, The Sprite [Hitode, Kappa]). Ten volumes of stories had appeared by 1982, before he had won the Akutagawa Prize. Letters from Sagawa may not be much more fantastic or macabre than some of his other tales, but it did take on a curious life of its own, both in its creation and its reception.

L’Affaire Sagawa

Letters from Sagawa owes much of its notoriety to the scandal surrounding its origins. It came into being when Kara’s penchant for the fantastic and grotesque connected to an ‘incident’ which occurred in the summer of 1981. On the evening of 15 June that year, Paris police had arrested a man identified as a Japanese student in front of his residence in the Sixteenth Arrondissement. He was held under suspicion of having brutally murdered a young Dutch woman, like himself a student enrolled at the Centre Censier of the University of Paris. Police had earlier been attempting to trace a suspicious-looking young Asian male who had jettisoned two suitcases by a pond in the Bois de Boulogne. The suitcases were discovered to contain human remains. Police had had little difficulty locating the cab driver who had unwittingly helped suspect Sagawa Issei carry the cases from his flat and take them to the nearby park (Le Monde 17/6/81:15).[3] News of the arrest reached Japan in time for evening newscasts the following day, and was then picked up by the major dailies on the seventeenth. Following standard journalistic practice, the suspect Sagawa Issei was at first only know as “A” in the Japanese media, although from its first reports Le Monde and other European media referred to both Sagawa and his victim, René Hartvelt, by name. The first, and what would prove to be one of the longest articles devoted to the “Sagawa jiken” by a broadsheet newspaper, was headed: “In Paris, Female Student Dismembered” (“Pari de jogakusei barabara”: Asahi 17/6/81: M 23). The article accompanying the header maintained a sober tone, but the header itself suggested the lurid imagery which would accompany discussion of this “incident” on its way to Kara’s literary recasting.[4]

According to his own thinly fictionalized account written well after the crime, Sagawa Issei had used his acquaintance Hartvelt’s multi-lingual skills as an excuse to invite her to his flat. He claimed that a Japanese professor staying in Paris had asked him to find someone who could provide good oral renditions of some particular German expressionist lyrics; he would pay Sagawa and a reader for a tape-recording. Hartvelt admitted to some ability in German but still found the request odd. Still, she agreed to help (Sagawa 1983: 100-01). For his part, Sagawa was only too aware that in the six months the young Dutch woman had studied in Paris, she had acquired a fluency in French far in advance of what he had gained in four lonely years of residency and study. After his arrest, concierges would surface attesting to his clumsiness and Harvelt’s skill with the language; when questioning Ph.D. candidate Sagawa, the police called upon the services of an interpreter (Asahi 17/6/81: M 23; Asahi 23/6/81: E 13).

She came to Sagawa’s flat and he sat her down before a tape-recorder. He handed her a volume of German poems and turning on the recorder, asked her to read an enigmatic lyric, “Abend” (“Evening”) by Johannes Becker. He meanwhile went and fetched a 22-caliber carbine fitted with a silencer. Several days before, Sagawa had invited his friend over for a meal, and while her back was turned, aimed the gun at her but it had failed to go off. This time it went off (Sagawa 1983: 58-71). After his transferral from police custody into the charge of the investigating magistrate, Sagawa was immediately committed for medical and psychiatric assessment. The case seemed to be in the hands of the doctors (Asahi 19/6/81: E 15).

In France, reporting of “l’affaire Sagawa” followed fairly predictable patterns, from the sober, sociological if ponderous approach of Le Monde to the scandal mongering of Photo (a lowbrow member of the Paris-Match syndicate), which found its editor in court for having reproduced photos taken of the dead victim by Sagawa (Le Monde 26/1/84: 10). Nor did Japanese journalists prove immune to sensationalization and an emphasis on the grotesque aspects of the brutal aftermath of the killing, rather than the crime itself or any sympathy for its victim.

During the beginning of the 1980s, the late Itami Juzo was, alongside his film work, editing an offbeat journal with the punning bilingual title Mon Oncle/ Monnonkuru (familiar wordplay about uncles and monocles). He and associates put together a special ‘l’affaire Sagawa’ issue in October 1981. It brought together a wide spectrum of French reporting, painstakingly translated into Japanese, headers, subheads and photo captions included; it also gave a fairly representative sample of Japanese journalists and intellectuals the forum of several extensive discussions (zadankai) to sum up reactions to a scandal that had echoed loudly in the tabloids and weeklies (shukanshi) in previous months. Yet even here, what the rival journalists really wanted to talk about was whether or not Sagawa had actually tasted his victim’s flesh; the intellectuals and writers rehearsed various theories about the social and psychological implications of cannibalism (Itami 1981: 82-89, 91-107).

Letters from Sagawa

The contact between Sagawa Issei and Kara – the actual exchange of letters denoted by the title of his story – began in a round about fashion. In October 1981 an acquaintance of the incarcerated Sagawa sent him a newspaper clipping. It was taken from the tabloid Sports News (Supotsu Nyusu). Kara Juro was to direct the film Boulogne, a cinematic transformation of the Sagawa incident; shooting was to begin in June 1982. With a budget of some 300,000,000 yen and Paris locations, the film was to be a rare exploration of the darker passions (Kara 1983: 146-47). “Please forgive me for writing to you so suddenly,” began Sagawa’s first letter to Kara on 12 November 1981. “I am the person who this June killed the young Dutch woman . . . and was arrested by the Paris police.” He mentioned having learned of Kara’s plans for a film and noted that for some time he himself had been contemplating a similar project. “Entitled Akogare [Yearning], it is a film in which a Western (or rather, Japanese) man yearns for a Western woman, and as the very consequence of his yearning, he kills the woman and devours her flesh” (Kara 1983: 149-50). Sagawa stated his willingness to make, even to star in a film about “my incident;” he hoped to be of assistance to Kara, answering questions or contributing to the scenario. He wrote as well that he hoped by December to be transferred to a psychiatric hospital, and that from there he might be allowed out once a week to work on the film project (Kara 1983: 27).

Kara was busier with his theatre troupe and fiction writing than with film in the late 1970s. He had had a small role in Shinoda Masahiro’s Demon Pond (Yashagaike) in 1979; in 1983 he adapted another writer’s novel for Kuroki Kazuo’s Bridge of Tears (Namidabashi). Where a sports reporter picked up the notion of a major film project based on the Sagawa is hard to know — though the report bares all the marks of Kara’s own bravado. It is unlikely to have been based on anything of substance. But after he had been contacted by Sagawa, Kara does seem to have aimed to stir up media interest in what had already become the draft of a long story. In July 1982 he travelled to Paris with an editor friend. He gave himself one week to soak up local colour and to make an attempt to visit Sagawa; he intended also to keep his eye out for a possible model for a Japanese female character he was planning to introduce into Sagawa’s “incident.” Within Letters from Sagawa, as well in an article about him which appeared in the Asahi Shinbun the month before the story’s publication, Kara portrayed his Paris trip as in addition the quest for a mysterious text – the anthology of poems from which the murdered woman had been reading aloud in her final moments (Asahi Shinbun 8/10/82: E 5).

The text which Kara eventually produced, Letters from Sagawa, is a strange exercise in the postmodern picaresque: a meandering hybrid of docu-fiction (imagine a short version of In Cold Blood written by a slapstick comedian), fiction and travelogue. Not so much a kind of story, it seems rather an anti-story or pre-story about a writer gathering material for a more straightforward account which never gets written, one that would presumably have been about visiting Sagawa and finding out some of the same sorts of things which preoccupied certain sections of the Japanese media.

The narrator had found himself engaged in correspondence with Sagawa Issei; he goes to Paris and tries to contact the imprisoned Sagawa via the law firm defending him, but is cold-shouldered in best Gallic fashion. The writer-narrator then resorts to a broken stream of messages and questions hastily scribbled in letters, on postcards or serviettes, supposedly to be dispatched to the incarcerated Sagawa. Meanwhile, he has found a room in a Left Bank hotel which by co-incidence is close to the apartment building where Sagawa’s victim had lived; the co-incidence provides scenes of parodic gothic humour in which the narrator skulks his way to the landing outside the door of the dead woman’s flat in order to leave a bouquet of white roses (this being a story that makes much play on “whiteness”) in the arms of a statue — of Isis — incongruously planted there. Another coincidence: he easily locates the bookshop, a German bookshop on the Rue de Rennes; and there it is, a copy of those very German expressionist lyrics Sagawa had handed to his victim. Paris itself seems fairly littered with barbaric, teasing signifiers. No more deterred by his lack of any knowledge of German than on forays into the city of signs by his minimal French, the Kara-narrator returns to his room and, with a newly purchased German-Japanese dictionary in hand, attempts to translate the poem Sagawa had chosen, “Abend.”

There may be distant echoes in this disjointed, ironic text of earlier Japanese works. In the nineteenth century, during the first era of the kicking-open of doors and imposed internationalization/kokusaika, parodies had appeared such as Kanagaki Robun’s Shanksmare to the West (Seiyo dochu hizakurige, 1870-76). Robun had sent his bumbling but canny Japanese rustics careering through Western societies and nations experienced as grotesque versions of the ideal and idealistic embodiments of modernity depicted by the Meiji enlightenment. Kara’s narrator follows in their footsteps. His, too, is an eminently caricaturable West. The exotic French decompose into grotesque clichéd images: “faint beads of sweat appear on the tips of blond noses passing by;” women’s blouses reveal “on approaching breasts, transparent blue veins akin to what were once called the Martian Canals (Kara 1983: 9).” Early on the story sets up a variety of parodic conceits via the classic Anglo-Irish fantasy travelogue, Gulliver’s Travels:

“That ‘yearning’ for the skin of ‘white’ people which for

long years tormented and drove you on is not something

that I, who have myself been looked-down upon by

women of foreign parts, cannot understand. But as it

seems the others you insinuated yourself close to were

always ‘white’ people, as though you had eyes for no-one

else, one can only consider you a strange sort of Gulliver

. . . . Reading your letter now, I end up convincing myself

that Gulliver, it may be, has pointed to the land of the white

giants and made me a chart for the voyage” (Kara 1983: 9).

The racial picaresque tone of the work is more often relayed through minor touches: Kara-narrator’s grandmother, in one of several textual non-sequiturs, is said to have served as maid in a “ketotaku”; the sign for a Kichijoji coffee shop called New Roxy seems, even in katakana script, to be “batakusai”; a phantom character describes Sagawa as having been “keto ni yowai” (Kara 1983: 20, 36, 99). The most likely first reaction of most readers coming across these musty old-fashioned terms of abuse is laughter. Ketotaku, in crude literal translation, is ‘house of a hairy foreigner’; batakusai, “butter/milk-smelling”; keto ni yowai, “to have a weakness for hairy foreigners.” The tone is teasing, consciously anachronistic, as Kara erodes the borders of ordinarily accepted terms and images regarding race and foreignness. The words do accumulate as Kara’s text wanders on its way. The result for a non-Japanese reader may unavoidably be akin to encountering the political and racial gaffes of certain Japanese politicians of the time: this does not seem to be a message intended for any but a Japanese audience.

Kokusaika, postmodernity

Debates concerning kokusaika, internationaliztion, were part of the cultural and political debates of Japan in the 1980s. The slogan was perhaps most closely associated with Nakasone Yasuhiro, prime minister from 1982 until 1987. During the decade, what Thatcher had become to Britain and Reagan to America, Nakasone seemed to be for Japan: a radical conservative leader out to privatize or scale back social welfare and/or state infrastructural institutions, discredit liberal political ideals, and pursue an aggressive foreign policy as geo-political strategy and domestic electoral tactic.

There is no doubt that things were changing in both the political and cultural landscapes before and during his years as prime minister. Hindsight suggests that commentators were right to emphasize how “Nakasone’s election came at an opportune moment in terms of the popular mood. A new nationalism was palpable in the early 1980s. . . . Asahi Shinbun reported that a majority of Japanese now regarded themselves as superior to Westerners” (Pyle 1987: 251). Nakasone may have had less real executive authority than Reagan or Thatcher, and his aggressive stance towards foreign policy often added up to little more than anti-Soviet rhetoric. But the agenda of a neo-nationalist revisioning of Japan’s past aggression in East Asia, which became an overt programme of right-wing intellectuals pursued ever since, matched by conservative political demands for increases in the military budget and for rewriting Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, the renunciation of warfare clause, has provoked neighbours such as Korea and China ever since. When, on 15 August 1985, the fortieth anniversary of Japan’s surrender — and Korea’s Liberation — Nakasone became the first postwar prime minister to make an official visit to Yasukuni Shrine, the reaction from Korea and China was immediate and angry. Nakasone did not repeat the gesture thereafter. He did not need to worry about letting down conservative voters; he had been re-elected already by a huge majority.

Nakasone spoke eloquently about Japan’s need to engage more widely with the world, certainly when he spoke for the record and for foreign consumption. The significance of language and communication was a key theme of kokusaika:

“It is imperative if [Japanese leaders] are to solve

vexatious international questions and remove sources

of friction, that they discourse eloquently and convincingly

with people who speak different tongues and have

different cultures, traditions and customs. To try to deal

with people of other nations via the traditional taciturn and

intuitive Japanese approach can only invite

misunderstanding” (Nakasone 1983: 14).

To domestic audiences, Nakasone was willing to say the sort of things nationalists and conservatives may have always said to one another in private but were increasingly declaring out loud, if not always for the record. Speaking to a seminar of members of his party in 1986, he could express other aspects of his agenda. Japan, the world’s number two economy and gaining fast, was preparing to engage fully in the international scene and gearing up to become the dominant information society; the American century was ending, Japan’s about to begin.

“And there is no country which puts such diverse

information so accurately into the ears of its people. It

has become a very intelligent society. . . . In America

there are many blacks, Puerto Ricans and Mexicans,

and seen on average, America’s per capita level of

intelligence, as gained through education and mass

media is still extremely low. Because Japan is such

a dense, vibrant society, a high-level information

society, a highly educated society, a society in which

people are so vibrant, unless of party’s policies

continually progress to suit the people’s appetite for

knowledge/information/ intelligence, our party will

falter” (Nakasone cited in Pyle 1987: 265).

Some well-educated translator with access to high-information technology provided an English version of Nakasone’s comments which winged its way into the American press the very next day. The reaction was immediate and angry, though the friction caused had less serious consequences, as time progressed, than a new counter-nationalistic discourse beginning to take shape in both China and Japan.

Nakasone operated in this case as though no one but Japanese people could possibly understand comments made in Japanese. Not ordinarily a problem for ordinary people. Yet a statesman calling for internationalization could be expected to have recognized that in “the wake of globalization, whether one is drawn along or remains resistant, one is translated ever more into translation” (Sallis 2002: 4). The uneasiness experienced by Americans reading Nakasone’s stray comments above is hard to avoid when reading the sort of racial vocabulary deployed by Kara in Letters from Sagawa. Although he wrote with a far different comic intent, the language may still seem offensive. And given the light-hearted attitude the text displays towards violence, fairly repellent. When a French translation of Kara’s story appeared, a Le Monde reviewer gave a balanced account of both the story and the crime from which Kara had spun it. His conclusion made an ethical point often absent from the initial reporting of “l’affaire Sagawa” in either France or Japan: “Kara . . . explores fantasies of an insane love,” yet ends up participating in “the lucrative exploitation of an atrocious drama” (Le Monde 26/1/84: 10).

One other theme circulating in the cultural atmosphere of the 1980s — one actually more international than internationalization — not only in Japan but in cultural and intellectual discourse in Europe, North America and elsewhere, was postmodernism. Debates over postmodernity were complex and have had far-reaching consequences, however casually the word postmodern may be used today (Storey 2005: 268-72).

For the limited purposes of understanding what is going on in Letters from Sagawa, I will take the shortcut of referring to a useful inventory of cultural traits assembled by Masao Miyoshi and Harry Harootunian in their 1989 landmark Postmodernism and Japan: ‘playfullness, gaming, spectacle, tentativeness, alterity, reproduction and pastiche’ (Miyoshi and Harootunian 1989: vii). Perhaps the only one of these notional traits not enacted by Letters from Sagawa with any positive force is alterity.

Throughout the tale, the language of others seems impossible. Nowhere is this enacted with more panache than in the narrator’s rather perverse treatment of a German poem: the famously difficult expressionist lyric “Abend,” by Johannes Becher. Kara-narrator requests further information from Sagawa about the poem his victim had been reading. The latter, in his written response, at first can recall a title of sorts and details of the cover of the anthology, but is uncertain about the author or precise title of the German poem in question. The name was something like “Jonathan”, writes Sagawa, and the title might be “Aben” (Kara 1983: 31), neither very German-sounding. While a Japanese acquaintance will eventually set the narrator straight about the German pronunciation of Johannes and “Abend,” he first tries out his own theory: “There may even have been an American Jonathan who dashed off to join the German Expressionist movement, and ‘Aben’ may be neither German nor English but a kind of cypher. Yet such fantasies may be no more than the delusions of someone with practically no gift at all for languages” (Kara 1983: 36).

The book version of Letters from Sagawa reproduces in the appendix a photo of the cover of the anthology in question: Lyrik des Expressionistischen Jahrzehnts (Kara 1983: 152-53). Next to the photo runs a portion of the German text of “Abend,” each stanza interpellated by Kara’s Japanese translation, one studded with parenthetical hunches and question marks. Kara manages both to translate and simultaneously call into question the very possibility or value of translation. His narrator comments in the body of the work on the chores of dealing with all these foreign words:

“This is probably a horrible translation. All I can feel

confident about is the bit about how bleak the future

looks. With the rest I just sort of strung together a

literal translation as the mood took me. I didn’t pick

German at university, and I’m hopeless at bluffing,

yet here I am in a cheap foreign hotel and, on top of

that, nitpicking through a foreign language — the

very fact is a huge farce” (Kara 1983: 63).

It seems almost as if one form of the postmodern sublime was, for Kara at least, a playful fending off of alterity, the pleasure of staying lost in translation.

The Akutagawa Prize

It is difficult at this distance in time to judge how ordinary Japanese readers of fiction reacted to Letters from Sagawa when it first appeared. Prime Minister Nakasone himself declared Letters from Sagawa a botched piece of work and the Akutagawa Prize devalued by association with it (Le Monde 13-14/3/83: 8). It seems safe to assume that this was a judgement based on the scandal surrounding Sagawa rather than a reading of Kara’s text. Of greater relevance is how Kara’s senior fellow writers judged the work on the way to according it Japan’s top literary award. Their judgements give some insight into the contentious climate within a literary sphere surrounded by more amorphous discourses of kokusaika or postmodernity.

The panel of judges for the 88th Akutagawa Prize included some of the best known male writers in the literary field: from a generation who started their careers before the war, Inoue Yasushi (1907-91); an intellectual who had helped lay the groundwork for postwar criticism, Nakamura Mitsuo (1911-88); and others then in late middle-age such as Yasuoka Shotaro (b.1920), Maruya Saiichi (b. 1925), Yoshiyuki Junnosuke (1923-94) and Oe Kenzaburo (b. 1935). Kaiko Takeshi (1930-89), better known by his pen name Kaiko Ken, who like Oe had emerged as a short story writer by the end of the 1950s, was also a member.

Kaiko’s career had taken him in more journalistic than purely literary directions than most of the others, but his was still a respected critical voice. His battlefield reporting for the Asahi Shinbun, collected in Vietnam War Chronicle (Betonamu senki 1965), is perhaps more memorable than the war-theme fiction he produced later in the decade. He had accrued extra cultural and political capital through his participation during the 1970s in the Beiheiren movement and its protests against the American invasion of Vietnam. At the end of the 1970s, Kaiko had published an open letter to Japanese writers in the journal Subaru. The title – “Ishoku tarite, bungaku wa wasureta!” – loosely translates as “Food in our bellies, clothes on our backs – Have we forgotten all about literature!?” It was a short, humorous broadside directed at his peers. “Let me pose a question in between the yawns of my midday nap. Our literature nowadays, creative, criticism, short works, anonymous columns, correspondence — is it because I’ve grown old that I can only feel the lot of it is just so much cold soup? Pure literature, impure literature, old, young, male, female — nothing but crude fakery, enough to make you lament that anyone could, with a straight face, make money like this” (Kaiko 1979:136). When throughout the 1980s literary scholars came to write about the growing sense of a crisis in fiction and the literary marketplace, Kaiko’s impromptu open letter was often singled out as a genuine premonition of the waning of serious literature as a significant cultural presence.

Kara Juro’s most eloquent supporter among what seems to have been a bitterly divided prize jury was Oe Kenzaburo. Oe found “Kara’s design sustained by a thorough theatricality; taking a real event as trigger, he displays a high level of intellectual, sensual fantasy.” Oe also noted that on the previous two occasions when the Akutagawa selectors had met, they had decided not to award the prize at all (Bungei Shunju March 1983: 395).

During the decade of the 1980s the continued viability of this literary and commercial institution had at times seemed in doubt. The twice-yearly prize was only awarded on nine of twenty occasions: the most dramatic gap since the fractious years of the immediate postwar era. This time around, the second-half of 1982, with seven promising authors on the short list, Oe thought the outlook for Japanese fiction seemed optimistic (Ibid). This may seem a remarkably up-beat assessment from a writer who by the middle of the 1980s would be openly concerned about the hollowing out of the cultural and political energies associated with postwar fiction. In an essay published just three years after the above comments, Oe would comment dismissively about a writer of fiction far more significant than Kara Juro, one arguably the first major winner of the modernity versus postmodernity literary stakes, Murakami Haruki.

“Among the Japanese writers of pure literature who

have attracted the most attention among young

people in the 1980s is Murakami Haruki, born in

1949 and reared during the period of Japan’s rapid

growth. . . . Murakami’s literature is characterized by

his determination not to take an active posture

toward society or even toward the milieu

immediately surrounding him. His method is to

passively submit to the influence of popular culture,

spinning out his inner imaginary as if listening to

background music” (Oe 1986: 3).

Critic Nakamura Mitsuo thought that while Letters from Sagawa seemed a writerly tour de force, it was hard to call it literary. Maruya Saiichi had no idea what Kara was going on about: “the plot has no logic, the characters lack any sense of reality. As for the style, there are many strange expressions and the choice of language is oddly distorted” (Bungei Shunju March 1983: 394-95). Perhaps any reader-writer of Maruya’s vintage may be forgiven for not being ready to reckon with Kara’s style in general or Letters from Sagawa in particular. Yet what was a constellation of narrative and stylistic features by way of becoming part of postmodern literary normality was a part of Kara’s storytelling as well. Murakami Haruki’s Wild Sheep Chase was one of the most successful literary works of 1982, and its combination of playfulness with language, rambling narrative form, fantasy, hapless narrator, lack of high-cultural seriousness — all have much more in common with Kara’s way of writing than mainstream engaged realism. One rather straightforward example of the latter would be the other winner of the 88th Akutagawa Prize, Kato Yoshiko’s Wall of Dreams.

Kaiko Ken thought that while some of the panel members had been too harsh in judging Kara’s work, he still found it little more than a fragment from a writer’s notebook (Bungei Shunju March 1983: 398). What makes Kaiko’s comments more than anecdotally interesting is that he was the only one of the panel to devote most of his comments to the other co-winner of the prize, Kato Yoshiko. Her story Wall of Dreams (Yume no kabe) is about as far in form and content from Kara’s postmodern gamesmanship as one could imagine. The first section is set in the west of China, and narrates in straightforward fashion the experiences of a young Chinese boy, family and neighbours caught between Chinese and Japanese armies during the war; the second part is told from the point of view of a Japanese girl whose family finds itself in Beijing at war’s end. The stories of the two young people are interwoven rather clumsily, but overall the work conveys real freshness and warmth. Oe rather patronizingly described Kato as a “writer who had lived almost thirty years all through the postwar, bearing with her the eyes and spirit of the girl of that past, solely to write this” (Bungei Shunju March 1983: 396).

Kaiko saw something more significant in Wall of Dreams. “Whether veteran or newcomer, one is part of a literary tradition, one peculiar to our country, which is extremely inept at depicting foreigners who really seem like foreigners. She has managed remarkably to capture the speech and behaviour of Chinese people who really seem Chinese” (Bungei Shunju March 1983: 398). Putting aside the challenge of defining what “really Chinese-like Chinese people” (Chugokujin rashii Chugokujin) may mean, the message is clear: Japanese literature should have room for, even a need for, writing that allows a space for others, alterity, the foreign.

Voyages pathologiques

In October 2006, a Reuters report relaying an article in the French press sent the term “Paris syndrome” into international media circulation. The term itself was coined by the Japanese psychiatrist Ota Hiroaki who, as noted by the BBC report cited above, had identified a complex group of emotional and psychological crises among a small number of Japanese visitors to Paris some years before. A long-term Paris resident, consultant at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne and advisor to the Japanese Embassy, Dr. Ota had been regularly called on by the Embassy to evaluate Japanese individuals brought in by emergency services or who have sought help at hospitals, and to oversee their initial treatment (Viala, Ota 2004: 32). He had published a popular treatment in Japanese concerning his experience treating Japanese visitors to Paris in 1991 (Ota 1991); the source of the recent journalistic interest in his work seems largely derived from a co-authored article in the psychiatric journal NERVURE (Viala, Ota: 2004). It is worth noting that among the general categories of difficulties encountered by those Japanese referred for medical assessment, such as breakdown in interpersonal relations, behavioural incomprehension, or disillusionment/depression, the first factor cited is “the language barrier . . . difficulties which can quite quickly create an incapacity for communication or be a source of serious [social] mistakes, leading to a sense of estrangement, anguish, isolation” (Viala, Ota 2004: 31-2).

The reports of Dr. Ota and colleagues make clear that what is at issue has nothing to do with rude Parisians and bad hotels, as some sections of the media might have it (see, for instance, the Japan Times editorial “Japanese and the ‘Paris Syndrome’”: 2006); it concerns, rather, a minuscule number of the annual one-million Japanese visitors to the capital who undergo emotional trauma and psychic malaise due to prior deep-seated problems, or an even smaller number for whom travel to Paris is itself part of an abiding delusional pattern of behaviour. It is also clear that other psychiatrists working with the emergency services in Paris recognize nothing especially Japanese about a link between travel to Paris and psychopathological incidents (Xaillé 2002). French doctors have themselves coined the term “Syndrome d’Inde” for the occasionally severe disturbances experienced by French travellers to South and South East Asia (Caro 2005: 44-5). [5]

It is an inevitable and understandable limitation of most psychotherapeutic accounts concerning voyages pathologiques — one common term for both travel which results in mental disturbance and for travel itself as a manifestation of psychological disorder — is that emphasis is placed on the suffering of individual travellers. We need a certain amount of historical distance perhaps to recognize how for some Japanese visitors to Europe, certainly in the past, travel might be experienced as a moment in the pathology of the West’s relationship with East Asia as well as a troubling individual event.

An established, middle-aged artist like Kara Juro may have seemed at ease playing with rather than engaging with alterity and the languages of others throughout the planning and writing which produced Letters from Sagawa; this is obviously not a stance likely to be taken by many young Japanese Francophile travellers, certainly not by Japanese students — or writers, artists, scholars — now or ever, given their serious personal investment in French language and culture. Even less so did Japanese and other non-Western students, intellectuals and writers in earlier decades have the freedom or sang-froid to treat lightly any rare opportunity to travel and study in Europe. One obvious difference between travellers then and tourists now is that in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, the former moved through a geopolitical space marked out by imperialist, colonialist and racialist discourses and practices. For East Asian and other non-European writers and intellectuals this meant making a long, expensive voyage at a time when “racial classifications between different population groups were so important that they often preceded and shaped real social encounters” (Dikötter 1997: 22). Frank Dikötter has described the experience of Chinese writers travelling to the US and Europe in the decades before the Second World War:

“It is understandable that some Chinese students

genuinely suffered from racial discrimination abroad,

although undoubtedly an element of self-

victimisation ad self-humiliation entered into the

composition of such feelings. More important,

however, they often interpreted their social

encounters abroad from a cultural repertoire which

reinforced the racialization of Others. Even social

experiences that had the potential to destabilise

their sense of identity were appropriated and

integrated into a racial frame of reference”

(Dikötter 1997: 22-3).

As is well known, Natsume Soseki, spent some miserable months in London a little over a century ago. Passages in his memoirs of the time vividly recall Franz Fanon’s dictum: “In the white world the man of colour encounters difficulties in the development of his bodily schema” (Fanon 1970: 78). “Everyone I see on the street is tall and good-looking,” wrote Soseki. “That, first of all intimidates me, embarrasses me. Sometimes I see an unusually short man, but he is still two inches taller than I am . . . Then I see a dwarf coming, a man with an unpleasant complexion — and he happens to be my own reflection in the shop window. I don’t know how many times I have laughed at my own ugly appearance right in front of myself. . . . And every time that happened, I was impressed by the appropriateness of the term ‘yellow race”’ (cited in Miyoshi 1974: 56-7).

It is in this context that I think we can at least understand some of what happened to Sagawa Issei in historical rather than scandal-mongering terms, because in his thinking and limited self reflection, little seems to have changed from Soseki’s days. Apparently in fragile mental health before coming to study in France, he found himself one among thousands of foreign students in Paris; he had ended up marking time, researching Japanese rather than French literature due to intellectual and linguistic limitations. And he seems to have found the experience of others and their language one of threatening self-annihilation. For Sagawa, anguish before the otherness of language seemed to impact directly on corporeal self-identity:

”To my question, how long have you studied French,

she startled me by replying, ‘Six months.’ ‘Six

months?!’ I had to ask again, thinking that it must be

because she was within one of the same European

languages (sic: onaji Yoroppa gengo no naka ni iru)

that in six months she could speak, read and write so

well. I could hardly say, I’ve been studying for over ten

years, I merely gazed up into her white face in a mood

of desperation. . . . Suddenly I looked at the glass front

door of the café and reflected there were the five of us.

A small Oriental in a charcoal blazer was submerged

amid large white-skinned men and women.

Instinctively I looked away” (Sagawa 1983: 32-3).

Monsters

Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein (1818) while still in her teens. The book bristles with harbingers of the modern era just taking shape. She seemed at times able to pre-experience a certain modern sense of what it might be like simultaneously to find oneself among others and frighteningly alone with the realization of your otherness to them. I am thinking of early in the novel, when the creature assembled from charnel house fragments escapes into the forest. Reborn into the mute signs of nature, he struggles still to translate experience into the symbolic world of human language. Inside an English book, in the setting of German-speaking Switzerland, the creature is learning French, having settled on the unwitting De Lacey family, themselves exiled into the forest, as his unwitting language tutors. “’I easily perceived that, although I eagerly longed to discover myself to the cottagers, I ought not make the attempt until I had become master of their language . . . I had admired the perfect form of my cottagers — their grace, beauty, and delicate complexions; but how was I terrified when I viewed myself in a transparent pool! At first I started back, unable to believe it was indeed I who was reflected in the mirror’” (Shelley 1985, p. 159).

What are we to do with our monsters? Postmodern monsters? Barak Kushner has written eloquently about what he called “cannibalizing Japanese media.” From newspaper reports to magazine coverage, and in books by and about Sagawa and his crime, individual journalists, writers and media figures have set in motion a sprawling discourse about cannibalism and the erotic, fetishism, even about Sagawa’s “victimhood” at the hands of a media which, Frankenstein-like, was his creator (Kushner 1997).

If there is something like a simple hard fact lying there at the origin of the “Sagawa Incident,” beyond the freakish output of bad writing and worse thinking (and Kara Juro may be no stranger to either) described by Kushner, it is an act of murder. A young woman was destroyed, a family devastated — two families, since like Renée Hartvelt, Sagawa Issei, too, had one. To dwell further here on the aftermath of that murder would, I believe, mean to participate in and to extend the violence of the crime, to aggrandize the Sagawa discursive marketplace, and to offer it academic cachet.

Postscript

Kara Juro disbanded the Situation Theatre Troupe in 1988, but only to start up a new drama group, the Kara-gumi (Kara Gang). The preceding year, after some eight years working with Kara’s troupe, Kim Sujin had organized his own gekidan, the Shinjuku Ryozanpaku.[6] He took with him from the old Situation Theatre the powerful actor Rokudaira Naomasa and Kobiyama Yoichi, who has become one of the Ryozanpaku’s lead actors and a playwright as well. Kim’s team carries on not only the spirit of the dramatic avant-garde of Kara’s generation but also its link with zainichi creative artists.

Kim himself has acted in both film and TV drama. He had a small role in the first zainichi film to prove both a commercial and critical success, Sai Yoichi’s All Under the Moon (Tsuki wa dotchi ni dete iru? 1993). In 1998 Korean director Park Chul-soo made a film version of Yu Miri’s Akutagawa Prize-winning story ”Kazoku Shinema” (“Family cinema” 1996). He cast Kim as a zainichi Korean film-maker, Yu Miri’s sister Eri as one of the family’s daughters, and veteran zainichi writer Yang Sogil (whose autobiographical fiction served as material for All Under the Moon as well) as the bumbling patriarch — a remarkable conjunction of theatrical, cinematic and literary talent brought together in a Korean-Japanese co-production. For his debut as director, Kim Sujin adapted Yang Sogil’s Through the Night (Yoru o kakete 1999), and made ample use in this Korean-Japanese production of his Ryozanpaku colleagues, along with giving minor parts to Kara and Ri Reisen. As noted at the beginning of the essay, Kim’s more recent film Glass Messenger (Garasu no tsukai 2005) has foregrounded Kara as story-teller, scriptwriter and actor, and revived interest in his earlier career.

One significant byproduct of Kim Sujin’s film-making is a documentary film included on the DVD of his first film, Through the Night: Yorukake — The Film ‘Through the Night’ Day by Day (Yorukake — Eiga ‘Yoru o kakete’ no hibi: see Kim 1999). It is more interesting than an average self-congratulatory “making-of” a short. The documentary introduces Kim’s regulars and a gaggle of fresh-faced volunteers who answered open advertisements recruiting amateurs to work on the film. The main job for the volunteers, a number of them zainichi Koreans, seems to be construction of a ghetto meant to represent the one where author Yang Sogil had grown up in postwar Osaka. The documentary follows them from the first stages of building the entire set themselves on a bleak patch of land in Suwon, South Korea, through the filming during which they have only minor roles, till the final conflagration of the fictional ghetto. Along the way, we again encounter Kara, Kim and other professionals, but the camera is also attentive to the young zainichi Koreans who recount, among other things such as exhilaration and fatigue, their experience of feeling not exactly either Japanese or Korean as they get to know Korean people over the months of the shoot. There is a space of cultural activity between national identities that the radical angura theatre, the literary field and zainichi film-making have explored since the 1960s. Kara Juro’s most significant cultural legacy exists here, I think, rather than in any film role or particular literary award.

Mark Morris is University Lecturer in East Asian Cultural History, University of Cambridge. Research and teaching involve mainly Japan’s minorities and Japanese and Korean film. His most recent article is “The Political Economics of Patriotism: the case of ‘Hanbando‘”, in Korea Yearbook 2007: Politics, Economics, Society (Brill). Forthcoming in 2008 is “Melodrama, Exorcism, Mimicry: Japan and the Colonial Past in the New Korean Cinema”, in What a Difference a Region Makes (Univ. of Hong Kong). Current research focuses on Korean film and film-makers during the late-colonial/wartime period.

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on December 1, 2007

Notes

[1] Here and elsewhere, unless otherwise indicated, information on Kara Juro, the Situation Theatre, Kim Sujin and the Shinjuku Ryozanpaku has been synthesized from entries in general online sources such as Amazon’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb), the Japanese Wikipedia, and from the following websites: the Kara-gumi; the film Glass Messenger (accessed 29 November 2006); Shinjuku Ryozanpaku (accessed November 2006).

[2] His stage name has even more complicated resonances given his family history. “His father had been fascinated by the romance of the Manchurian ‘new frontier;’ his maternal grandfather had worked for the South Manchurian Railroad; and his mother . . . has been raised in Manchuria and Korea” (Goodman 1988: 231).

[3] References to Le Monde are cited by date (day/month/year), page number, and refer to final editions; Asahi Shinbun is cited similarly, with indication of edition (M morning, E evening).

[4] Early reports in the Asahi Shinbun displayed a nervous glance over the shoulder that was still common in Japanese press attitudes towards the country’s overseas image. It was reported that newspapers less restrained than Le Monde such as France Soir had given the story front-page coverage and screaming headlines, for example: ‘Ripper of the Bois de Boulogne – a cannibal’, etc. (Asashi Shinbun 17/6/81: M 23). A sense of collective gloom and paranoia would seem to characterize the paper’s long commentary two days later, which brooded on the implications of the crime for the 2700 Japanese students residing in France. The piece was accompanied by a rather staged-looking photo from the AP Wire Service showing a young Frenchman gazing with concern at the front page of that same number of France Soir. The commentary concluded that ‘now when the eyes of the world are sharply focused on Japan, one can only emphasize that students residing abroad must have a renewed sense of their responsibilities’ (Asahi Shinbun 19/6/81: E 12).

[5] For more concerning voyages pathologiques (in Japanese byoteki ryoko), see Ota 1991: 106-18. It is far from surprising that large-scale tourism, as well as migration from underdeveloped countries, should bring about numerous cases of dysphoric experiences that end up requiring medical treatment. And while the relatively affluent tourist may suffer psychically as keenly as the impoverished migrant worker, it does seem likely that the work of a psychiatrist such as Dr. Joseba Achotegui (Achotegui 2004), who coined the term Ulysses syndrome, in the treatment of North African and sub-Saharan migrants may be of more crucial importance for the future of Europe. Dr. Achotegui and colleagues working in the cities of southern Spain are confronting the results of a massive historical wave of illegal immigration. Particularly in its symptomatological description of states of mourning and grief, Achotegui’s work is reminiscent of accounts from another wave of migration, that of Koreans to Japan during the years of the Japanese empire. It may also prove relevant for understanding many expressions of han (the deep, lacerating sense of longing and loss), long a motif of Korean cultural discourse (see Grinker: 2002).

[6] Shinjuku is the Tokyo neighbourhood. Ryozanpaku means something like “Robbers’ Den.” It is a witty allusion to the famous “Liangshan Marshes,” a place known from the classic Water Margin as a hideout for brigands.

References

Achotegui, Joseba (2004) “Emigrar en situación extrema: el Síndrome del immigrante con estrés crónico y múltiple (Síndrome de Ulises)”. Norte de Salud mental, no. 21, pp. 39-52. Available here (accessed 20 January 2007).

Bungei shunju (March 1983). Akutagawa Prize section: pp. 393-503.

Caro, Federico A (2005) “Voyage Pathologique: Historique et Diagnostiques Differentiels”. Available here (accessed 28 December 2007).

Dikötter, Frank (1997) “Racial Discourse in China: Continuities and Permutations”, in The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspective (ed.) Dikötter, Hurst & Co, pp. XXX.

Fanon, Frantz (1970) Black Skin White Masks, (trans.) Constance Farrington, Paladin.

Goodman, David (1988) Japanese Drama and Culture in the 1960s, M.E. Sharpe.

Grinker, Roy Richard (2002) Korea and Its Futures: Unification and the Unfinished War, Palgrave Macmillan.

Itami, Juzo (1981) (ed.) Mon Oncle/ Monnonkuru 1:4 (October).

“Japanese and the ‘Paris Syndrome'” (2006) Japan Times Online, 29 October . Available here (accessed 22 January 2007).

Kaiko, Takeshi (1979) “Ishoku tarite, bungaku wa wausreta!?” Subaru (July), p. 136.

Kara, Juro (1983) Sagawa-kun kara no tegami: Butokai no techo, Kawade Shinsha Shobo.

Kim, Sujin (1999) (dir.) DVD Yoru o Kakete/Through the Night, Toei Video.

Kushner, Barak (1997) “Cannibalizing Japanese Media: The Case of Issei Sagawa.” Journal of Popular Culture. 31:3 (Winter).

Miyoshi, Masao (1974) Accomplices of Silence, University of California Press.

Miyoshi, Masao and Harootunian, H.D. (1989) (eds.) Postmodernism and Japan. Duke University Press.

Nakasone, Yasuhiro (1983) “Towards a Nation of Dynamic Culture and Welfare.” Japan Echo X:1 (Spring ), pp.12-18.

Oe, Kenzaburo (1986) “Postwar Japanese Literature and the Contemporary Impasse: Account of a Participant Observer”, in The Japan Foundation Newsletter. XIV:3 (October), pp. 1-6. [The longer original is “Sengo bungaku kara konnichi no kyujo made”, Sekai (March 1986).]

Ota, Hiroaki (1991) Pari shokogun, Toraberu JÄnaru.

Pyle, Kenneth B. (1987) “In Pursuit of a Grand Design: Nakasone Betwixt the Past and the Future.” The Journal of Japanese Studies. 13:2 (Summer), Juro pp. 243-70.

Sagawa, Issei (1983) Kiri no naka (In the Mists), Hanashi no Tokushu.

Sallis, John (2002) On Translation, University of Indiana Press.

Shelley, Mary (1985 [1818].) Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Penguin

Storey, John (2005) “Postmodernism” in New Keywords: A Revised Vocabulary of Culture and Society, (eds.) Tony Bennet, Lawrence Grossberg and Meaghan Morris. Blackwell Publishing, pp. 269-72.

Viala, A., Ota, H et al. (2004) “Les Japonais en voyage pathologique à Paris: un modèle original de prise en charge transculturelle”, NERVURE 5:5 (June), pp. 31-4. Available here

(accessed 21 January 2007).

Wyatt, Caroline (2006) “‘Paris Syndrome’ Strikes at Japanese”, BBC News International 20 December. Available here (accessed 24 January 2007).

Xaillé, Anne (2002) “Voyage pathologique: voyager rend-il fou?”, Actualité: Le magazine. Available here (accessed 28 December 2006).